Abstract

Importance

Although autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is known to be heritable, patterns of inheritance of sub-clinical autistic traits in non-clinical samples are poorly understood.

Objective

To determine the familiality of Social Responsiveness Scale (SRS) scores; we hypothesized that sub-clinical autistic traits would be associated in families.

Design and Setting

Nested case-control study within a population-based longitudinal cohort.

Participants

Participants were drawn from the Nurses’ Health Study II (NHS II), a cohort of 116,430 nurses. Cases were index children with reported ASD; controls were frequency matched by years of case births among those not reporting ASD. Of 3161 eligible participants, 2144 returned SRS forms for a child and at least one parent and were included in these analyses.

Exposure

SRS scores, as reported by nurse participants/mothers and their spouses, were examined in association with liability to ASD using crude and adjusted logistic regression. Child SRS scores were examined in association with parental SRS scores using crude and adjusted linear regression, stratified by case status.

Main Outcome Measure

ASD, assessed by maternal report, validated in a subgroup with the Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised.

Results

1,649 individuals were included in these analyses, representing 256 ASD cases, 1,393 controls, 1,233 mothers and 1,614 fathers. Index child SRS scores confirmed reported diagnoses. We report for the first time in a large epidemiologic sample that elevated parental quantitative autism traits (QAT) index risk for clinical ASD among offspring. The effect was most pronounced for fathers and for spousal pairs concordant for QAT elevation, which occurred more often than predicted by chance, due to significant preferential mating for QAT. Elevated parent scores significantly increased child scores in controls, corresponding to an increase in approximately 20 points.

Conclusions and Relevance

These findings support the role of additive genetic influences in ASD, underscore the potential role of preferential mating in ASD population genetics, and suggest that typical variation in parental social functioning can produce clinically significant differences in offspring social traits.

Introduction

Genetic factors are known to be involved in autism spectrum disorders (ASD); however, at present, ASD etiology is not well understood. There is wide phenotypic variability in severity and social functioning of affected individuals, and evidence suggests that this variation in social functioning extends into the general population in what may be a continuum of autistic-like traits1, often referred to as the broader autism phenotype (BAP) or quantitative autistic traits (QAT)2, 3. A number of studies have suggested intergenerational transmission of QAT1-4, but patterns of family transmission are not well understood, and large-scale epidemiologic investigations utilizing affected and unaffected families are lacking.

The Social Responsiveness Scale (SRS5) is a 65-item questionnaire that has been used in numerous studies of QAT. This self- or informant-report measure was designed to assess social functioning6; there is both a child version (ages 3-18), typically completed by a parent or care-giver, and an adult version (SRS-A, with slightly modified wording for individuals over age 181, 7), typically completed by a spouse, close relative or friend. The SRS has been shown to have strong psychometric properties, with high internal validity, reliability, and reproducibility, and it has been validated against a widely implemented developmental history interview, the Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised (ADI-R), with strong results (r=0.7 for SRS scores and ADI-R algorithm scores for DSM-IV criteria)8, 9. Established thresholds reliably distinguish ASD children from both non-affected children and those with other conditions such as mental retardation9, 10. Use of the SRS in both general population and affected samples has demonstrated that SRS scores are continuously distributed and are not related to intelligence quotient or age1, 6, 9, 11.

A number of family studies using the SRS have been conducted10-18, some providing evidence for heritability of QAT according to SRS scores. A study of unaffected twin pairs and their parents showed that sub-clinical elevations in SRS scores were associated with elevations in SRS scores of offspring1. QAT elevations have also been found to aggregate in the siblings of ASD affected probands12, 19. However, many prior family studies have had relatively small sample sizes3, 4, limiting power to fully examine associations. Previous studies have also focused on simplex (families with one child affected with ASD) versus multiplex (families with >1 affected child) families2-4, 20, and/or relied on use of clinic-referred populations2, 4, 21, 22, or used twin pairs or families with twins1, 8, 13, 14, 17. However, patterns of family inheritance may differ in clinical populations or multiplex families due to differences in comorbidity and severity levels. Large studies drawn from the general population are needed to better understand the transmission of sub-threshold autistic traits in order to learn more about the inheritance of ASD and QAT.

The purpose of this study was to examine familiality of SRS scores in adults and children with and without ASD drawn from a non-clinical sample. In particular, we sought to examine whether 1) higher parent scores were associated with increased risk of ASD, and 2) higher parent scores were associated with higher child scores, within both ASD case families and control families. We hypothesized that parent scores of affected children would, on average, be higher than those of controls, due to QAT in parents, and that high parent scores would be associated with higher child scores due to intergenerational transmission of QAT. Given prior work, we also hypothesized there would be evidence for assortative mating as indicated by high mother-father correlation in SRS scores.

Methods

Study population

Participants were part of a nested case-control study drawn from the Nurses’ Health Study II (NHS II), a prospective cohort of 116,430 female nurses aged 25-43 when recruited in 1989. Since that time, women have completed mailed questionnaires every 2 years. Additional details of the cohort have been previously reported23, and all NHS II questionnaires are available online at http://www.channing.harvard.edu/nhs/?page_id=246. In 2005, participants were asked whether any of their children had autism, Asperger syndrome, and ‘other autism spectrum.’ In 2007, we initiated a pilot study of ASD cases and controls, shortly followed by a full-scale study; the details of this nested case-control study (combined pilot and full-scale) have been previously described24. Briefly, a total of 756 cases and 3,000 controls were included in these mailings. Controls were randomly selected among those women not reporting any ASD in 2005, and were frequency matched by years in which case mothers reported births (as at the time no information on case year of birth was available). 3,383 women responded (including 636 cases; average response rate 90%), and 164 women (including 51 cases) indicated they did not wish to participate. For these analyses we excluded: adopted children (n=15); case mothers who failed to confirm a diagnosis of autistic disorder, pervasive developmental disorder not otherwise specified (PDD-NOS), or Asperger syndrome (n=11); controls who indicated one of these diagnoses (n=5); and children with the following genetic disorders (n=16, including 12 cases): Fragile X syndrome, Down’s syndrome, Tuberous Sclerosis, Trisomy 18, Jacobsen syndrome (11q deletion), or Rett’s disorder. Of the 3,161 individuals meeting these criteria, individuals who did not return any SRS form (n=1,014) and those who returned unusable forms (n=3; >10% of items missing, as per publisher instructions) were excluded, leaving 2,144 participants. Finally, these analyses include only those participants returning an index child form (child or adult version) as well as at least one parent form (n=1,649; ~80% of SRS eligible group and ~50% of eligible nested case-control group).

Measures

SRS forms (SRS- and SRS-A) were mailed to participants as part of the nested case-control study, in order to examine QAT in this population. Participants with index children known to be over 18 years of age were sent the adult version of the SRS, the SRS-A.

For forms with <10% missing, item median values were substituted for missing values, as recommended by the publisher, using the median for that item within the same gender, case status, and form type (adult or child form). Total raw SRS scores were calculated by summing the scores of positive and negative-coded items6. For all child forms, T-scores (with scoring by child’s sex) and cut-off ranges (normative range: T score of 59 or less; mild ASD range: T score of 60-75; severe ASD: T-score of 76 or higher) were calculated according to publisher criteria6.

In 50 randomly selected case mothers who indicated willingness, the child’s ASD diagnosis was validated by a trained professional who administered the ADI-R25 (the gold-standard diagnostic instrument) over the phone. Of these, 43 (86%) case children met cut-off scores in all domains for an ADI-R diagnosis of autism; the remaining individuals either missed the diagnostic cut-off by one point on one domain (n=6) or met the cut-off for 1 domain (n=1) and came close to cut-offs for the remaining domains. All individuals met the age-of-onset criterion and at least one domain cut-off, indicating presence of autistic spectrum behaviors. In the subgroup of case children with both SRS forms and ADI-R (n=49), agreement between the measures was high (93% met ASD/autistic disorder criteria on both measures).

Statistical analyses

Student’s t-tests were used to compare mean raw scores between cases and controls, for index children and parents. Within-family correlation of SRS scores was examined by calculating Pearson correlation coefficients for mother-father, mother-child, and father-child forms by case status, and by examining scatter plots.

We examined case status in association with elevated parent scores via chi-squared test as well as crude and multivariate adjusted logistic regression analysis. Elevated SRS scores in parents were defined as the top 20% of the score distribution for mothers and fathers respectively; high scores were compared to the remaining 80% of the distribution as the referent group. Associations with mother- and father-elevated scores were examined separately. We also examined associations with ASD when either parent had an elevated score, and when both parents had elevated scores (concordantly elevated). In analyses using quintiles of parent scores, tests of trend were conducted for mother and father scores.

Next, we examined whether the distribution of child scores was shifted according to elevated parent scores by using t-tests and crude and multivariate linear regression, stratified by case status. Continuous parent scores, the binary cut-off variable for elevated parent scores, and quintiles of parent scores were examined for these analyses.

For all analyses, mother and father scores were examined separately to assess whether transmission of liability in ASD traits might have parent-of-origin effects. Secondary analyses stratified by child sex were conducted in order to examine the potential for sex-specific transmission. Variables tested as potential confounders, due to a-priori knowledge of associations with ASD and QAT, in all multivariate models included: child sex (when not defining strata), child year of birth, birth order, maternal and paternal age at index birth, household income level, race (binary indicator for white/other), maternal pre-pregnancy obesity, and maternal history of depression. We also tested adjustment for divorce status and reported child depression or ADHD, given the potential influence of these factors on rating SRS forms. Mother/father score models also examined the effect of adjusting for the other parent’s score.

Sensitivity analyses

All analyses were also conducted within the subgroup of complete trios (mother, father, and index child forms; 73% of the study population). Multiple imputation26, 27 analyses, using Proc MI/ MIANALYZE in SAS, of missing parent scores were conducted to examine potential bias due to a missing parent form.

Results

Basic characteristics of the study population are shown in Table 1. The study group is representative of the NHS II as a whole in terms of income and race, but is slightly younger at baseline than the overall cohort. Individuals from our follow-up study who did not return SRS forms but were otherwise eligible did not significantly differ from those included in these analyses on basic demographic characteristics and other factors like divorce or smoking status and child low birth weight.

Table 1. Basic characteristics and response information of the study population by case status (n=1649).

| Cases N= 256 | Controls N= 1393 | |

|---|---|---|

| mean (std) | ||

| Maternal age at index birth | 32.5 (4.6) | 32.5 (4.7) |

| Paternal age at index birth | 34.6 (5.8) | 34.5 (5.5) |

| Household income level, 20011 | 7.3 (1.7) | 7.5 (1.7) |

| Index child year of birth | 1989 (5.7) | 1990 (6.1) |

| Index child birth order | 1.8 (0.9) | 2.1 (1.1) |

| Index child age at SRS | 19.1 (5.9) | 19.0 (6.2) |

| Mother age at SRS | 52.2 (4.6) | 51.5 (4.3) |

| Father age at SRS | 54.2 (5.5) | 53.6 (5.4) |

| n (%) | ||

| Race- Caucasian | 236 (92%) | 1309 (94%) |

| Maternal reported clinician-diagnosed depression2 | 86 (34%) | 271 (20%) |

| Divorced/separated as of 2001 | 22 (9%) | 84 (6%) |

| Child age category | ||

| 5-12 | 30 (12%) | 168 (12%) |

| 13-18 | 99 (39%) | 559 (40%) |

| 19+ | 127 (50%) | 666 (48%) |

| Male index child | 211 (82%) | 713 (51%) |

| Female index child | 45 (18%) | 680 (49%) |

| Index child firstborn | 116 (45%) | 447 (32%) |

| Index child ADHD (maternal report) | 116 (45%) | 135 (10%) |

| SRS forms completed | ||

| Index child form3 | 256 (100%) | 1393 (100%) |

| Mother forms | 240 (94%) | 993 (71%) |

| Father forms | 242 (95%) | 1372 (98%) |

| Complete trios | 226 (88%) | 972 (70%) |

Household income categories, collected on a previous NHS II biennial questionnaire, defined as: 1) <15,000, 2) 15-19,000, 3) 20-29,000, 4) 30-39,000, 5) 40-49,000, 6) 50-74,000, 7) 75-99,000, 8)100-149,000, 9)150,000. 20% did not provide income information.

As reported on any NHS II biennial questionnaire.

Child or adult version of SRS available.

All index child and father SRS forms were completed by the nurse participants (ie, the index child’s mother), while mother forms were completed by the nurse’s spouse/the child’s father or a close relative. SRS and SRS-A raw scores by group are shown in Supplementary Table A. As expected, case index child SRS scores were significantly higher than control scores (average ~80 points higher in cases, p<0.0001), and 93% of cases fell within the ASD range according to SRS-score established cut-offs (T-score of 60 or higher), compared to only 7% of controls. Overall, mean raw scores were slightly higher for males than females (fathers higher than mothers, and male controls v female controls, p=0.0001), but scores did not differ by sex for case children. Index child SRS scores were not associated with age, or, for cases, with age at diagnosis. Scores in the study population are provided in online eTable 1.

Family correlations

The correlation of scores between mother and father forms was moderate for both cases and controls (case r=0.25; control r=0.34). Other within family correlations were low for cases (mother-child r=0.02; father-child r=0.13) and moderate for controls (mother-child r=0.30; father-child r=0.42). Examination of scatter plots did not reveal any non-linear patterns.

Parent scores in association with ASD

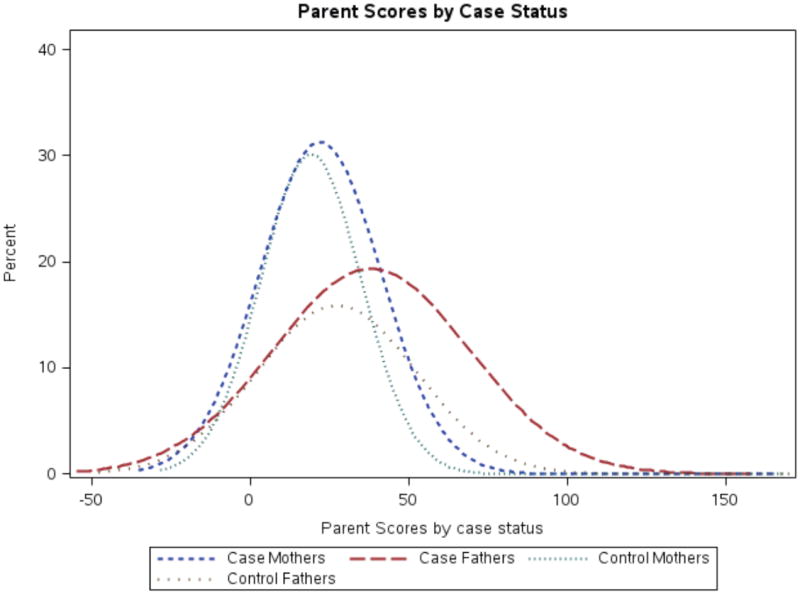

Mean parent scores were significantly higher among cases than controls (mother forms p=.03; father forms p<.001). We observed fairly dimorphic distributions between the sexes, and the distribution of case father scores was shifted noticeably higher as compared to that of control fathers (Figure 1). Cases were significantly more likely to have a parent with an elevated SRS-A score; 41% of cases and 28% of controls had at least one parent with an elevated score (p<0.0001); 12% of cases and just 6% of controls had concordantly elevated parent scores (p=0.0008). Case father (p<0.0001; 33% of cases v 18% of controls) but not mother scores (p=0.40) were significantly higher than in controls. These associations remained significant in adjusted analyses (Table 2); liability to ASD was increased by approximately 90% among children with concordantly elevated parent scores (OR=1.85, 95% CI 1.08, 3.16) and by approximately 50% when either parent’s score was elevated (OR=1.52, 95% CI 1.11, 2.06). By parent, father elevated scores significantly increased risk of ASD (OR=1.94, 95% CI 1.38, 2.71), but no association was seen for mother elevated scores. Associations were somewhat stronger in male children (Table 2), although there were fewer females. When utilizing quintiles of parent scores, rather than the binary cut-off variable, results were similar; the highest quintile of father’s scores, compared to the lowest, corresponded to a significant increase in odds of ASD (OR=2.55, 95% CI 1.55, 4.21). While the test of trend was significant (p=0.0003) for father quintiles, ORs for quintiles 2-4 were all approximately 1.4 (with 95% CI ~0.8-2.4). No significant associations were observed in the analyses of quintiles of mother’s scores.

Figure 1. Distribution of parent SRSA scores according to child ASD status.

Figure shows density plot of smoothed distribution of parent SRS-A scores as grouped by case status and mother/father. Values below 0 are due to the plotting of the smoothed density distribution, rather than actual SRS-A score.

Table 2. Risk of ASD according to parent elevated SRS-A scores.

| Case/control exposed n1 | Crude | Adjusted Model 12 | Fully Adjusted Model3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| In full study group (n=1649)4 | ||||

| Father elevated score | 79/248 | 2.20 (1.62, 2.97) | 2.10 (1.54, 2.88) | 1.94 (1.38, 2.71) |

| Mother elevated score | 54/199 | 1.16 (0.82, 1.63) | 1.10 (0.77, 1.56) | 0.95 (0.65, 1.40) |

| Either parent elevated score | 105/389 | 1.80 (1.36, 2.36) | 1.71 (1.28, 2.27) | 1.51 (1.11, 2.05) |

| Both parents elevated scores | 28/58 | 2.23 (1.38, 3.59) | 2.02 (1.22, 3.32) | 1.85 (1.08, 3.16) |

| In male children (n=924)5 | ||||

| Father elevated score | 68/127 | 2.34 (1.65, 3.33) | 2.27 (1.59, 3.22) | 2.05 (1.40, 3.01) |

| Mother elevated score | 48/104 | 1.29 (0.87, 1.91) | 1.26 (0.85, 1.87) | 1.13 (0.73, 1.73) |

| Either parent elevated score | 90/202 | 1.88 (1.37, 2.59) | 1.84 (1.34, 2.53) | 1.62 (1.14, 2.29) |

| Both parents elevated scores | 26/29 | 2.71 (1.55, 4.74) | 2.53 (1.44, 4.44) | 2.38 (1.30, 4.38) |

| In female children (n=725)6 | ||||

| Father elevated score | 11/121 | 1.60 (0.78, 3.28) | 1.60 (0.77, 3.30) | 1.55 (0.73, 3.28) |

| Mother elevated score7 | 6/95 | 0.63 (0.26, 1.54) | 0.58 (0.24, 1.43) | 0.47 (0.18, 1.22) |

| Either parent elevated score | 15/187 | 1.32 (0.69, 2.51) | 1.26 (0.66, 2.41) | 1.16 (0.59, 2.28) |

| Both parents elevated scores7 | 2/29 | 0.77 (0.18, 3.33) | 0.70 (0.16, 3.07) | 0.59 (0.13, 2.74) |

Number of cases and controls respectively with parent score in the top 20% of the study distribution.

Adjusted for: child year of birth, child sex, maternal age, and household income.

Adjusted for: Model 1 covariates plus reported maternal diagnosed depression and child ADHD. Further adjustment for race, divorce status, paternal age, or maternal pre-pregnancy obesity did not materially alter results, with the exception of both parent elevated scores in the full study group: estimate was slightly attenuated with further adjustment for divorce status, OR=1.72, 95% CI 1.00, 2.96. Adjustment of mother models for father scores further attenuated results; adjustment of father models for mother scores did not materially alter results.

Full study group analysis n for parent models as follows: 1614 individuals for father, 1233 for mother, 1649 (full group) for either parent, 1198 for both parents.

Analyses conducted within male children only. N for parent models as follows: 905 individuals for father, 714 for mother, 924 for either parent, 695 for both parents.

Analyses conducted within female children only. N for parent models as follows: 709 individuals for father, 519 for mother, 725 for either parent, 503 for both parents.

Results should be interpreted with caution given model instability due to small exposed case n.

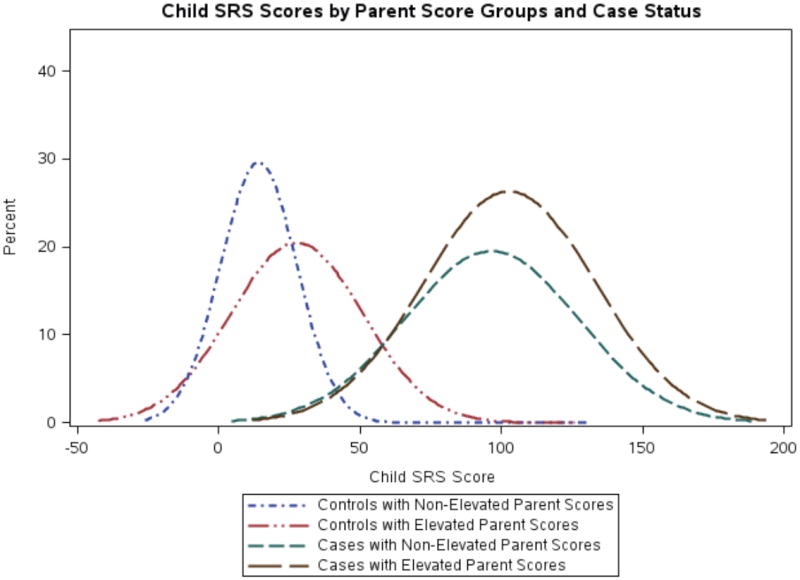

Parent scores in association with child scores

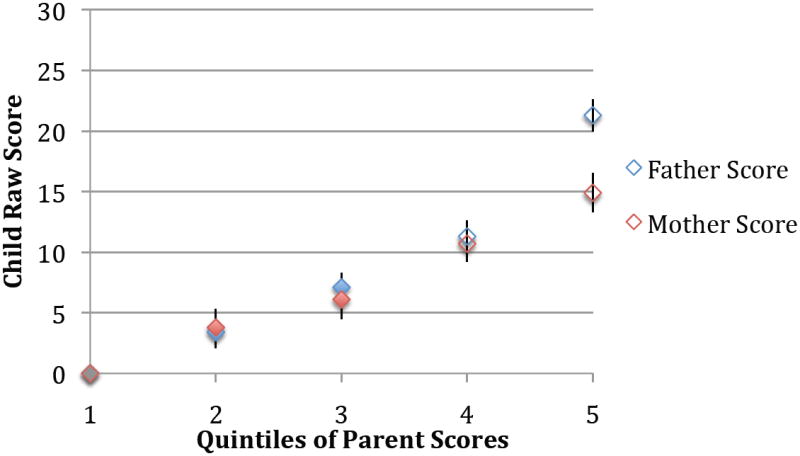

The child score distribution was shifted towards higher scores when parent scores were in the top 20% of their respective (mother or father) distributions (Figure 2), particularly for controls. Both case and control index child scores increased on average when parent scores were elevated (by ~2-9 points in cases and ~10-23 points in controls in adjusted analyses, depending on whether mother’s, father’s, either parents’, or both parents’ scores were in the top 20% of their respective distribution; online eTable 2). However, these differences were only statistically significant in controls. The strongest average increases in child scores occurred with parent concordantly elevated scores in controls (23 points, p<0.0001). Examination of quintiles revealed similar results (Figure 3), and child scores increased as mother or father quintiles increased (tests of for both mother’s and father’s quintiles p<0.0001). Among cases, no significant associations were seen in quintile analyses, though child scores did increase slightly as the father’s quintile increased. Stratified by child sex (online eTable 2), increases in child score according to parent score were slightly greater among male controls than among female controls, but were overall similar. Among cases, there was a suggestion of greater increase in female child scores according to parent score increases, though small numbers led to unstable estimates.

Figure 2. Distribution of child SRS scores according to parent elevated scores.

Figure shows density plot of smoothed distribution of raw child SRS scores as grouped by parent elevated scores (as defined by either parent score in the top 20% of the distribution of SRS-A score). As for Figure 1, values below 0 are due to the plotting of the smoothed density distribution, rather than actual SRS score.

Figure 3. Child SRS score according to parent SRSA score among control children.

Figure displays results of multivariate linear regression for the association between child raw SRS score as predicted by quintiles of parent SRS-A score, with the parent quintile=1 used as the referent for respective mother and father models. Results adjusted for child year of birth, child sex, maternal age, household income, reported maternal depression, and reported child ADHD. Error bars represent standard errors. Mother and father models were run separately; adjustment of mother scores for father scores slightly attenuated results, while adjustment of father scores for mother scores did not materially alter quintile estimates. Tests of trend were significant for both mother and father models (p<0.0001 for both).

Sensitivity analyses

Results were materially unchanged in the subgroup with complete trio data. In analyses using imputed missing values, results were also similar and yielded the same conclusions.

Discussion

This is the first large epidemiologic sample demonstrating that parental QAT elevations index risk for ASD among offspring. We found evidence that parents of children affected with ASD had greater social impairment than control parents as measured by the SRS, and that concordantly elevated parent SRS scores significantly increased liability to ASD in the child. Further, the heritability of broader autism traits was also supported through significant increases in child scores according to parent-elevated scores among individuals not affected with ASD.

That child liability to ASD increased significantly when parental SRS scores were in the top 20% of the distribution supports the vast literature suggesting the strong heritability of ASD12, 28. However, we also noted slight differences in risk according to whether the elevated score was the father’s, mother’s, either parent’s, or both parents. In particular, concordantly elevated parent scores were found far more often than expected by chance in cases as compared to controls, and nearly doubled risk of ASD. The magnitude of the association was also similar when only father scores, but not mother scores, were elevated. A few previous studies have suggested transmission of ASD through the father, or evidence of the QAT in fathers but not mothers2-4. However, not all studies support sex-specific genetic influences1, 13; sex differences are further discussed below. While a number of prior reports have examined family patterns of QAT in unaffected (most often, twins and their parents) or affected (most often drawn from clinics) populations separately, none have specifically examined liability to clinical ASD according to parent scores by comparing cases to controls.

We did not see significant increases in child scores with increased parent scores in cases; however, this is not surprising given the highly elevated scores in case children. This also speaks to the lower within-family correlation of scores among cases than among controls. However, the fact that control children’s scores increased significantly with increases in parent’s scores supports the familial transmission of QAT in the general population. Prior studies have also suggested this heritability in unaffected individuals 1, 13, 14. These findings, combined with our own, provide evidence that social functioning is highly heritable, and suggest that transmission of autistic traits is not seen only in families with a child (or children) with ASD, but also in families whose members fall below the clinical threshold for ASD.

While there was some suggestion of sex differences in our findings, both through the somewhat stronger increased liability to ASD in male children with elevated parent scores, and the apparently stronger influence of the father’s score, which may suggest a parent-of-origin effect, there are other potential explanations for these results. Perhaps the most obvious is that males are at increased risk of ASD simply due to their sex; a corollary is that females may have decreased phenotypic expression of these traits for a given level of genetic susceptibility. In support of the latter, two recent studies examining recurrence risk in half-sibs and full-sibs found strong evidence for transmission through unaffected mothers29, 30. Moreover, Robinson et al. demonstrated higher mean QAT scores in the co-twins of female autism probands compared to male autism probands in two large samples, suggesting a higher level of familial loading required to bring females to the threshold of clinical affectation31; in contrast, there was no evidence of recurrence of clinical autistic syndromes among siblings of male versus female probands in a Danish population-based sample of approximately 1.5 million30. As in the current study, Virkud et al found higher SRS scores in unaffected brothers and fathers of multiplex probands3. However, none of these findings clearly refute or support a sex-specific transmission model. A more detailed discussion of sex differences related to this topic is included in Constantino and Charman32. We also observed one of the most sexually dimorphic distributions in any ‘normative’ population in the parents of our study, perhaps related to the use of a nurses’ cohort. It should also be noted that our study did not have the power to fully examine sex differences within cases, due to the relatively small number of female cases (n=45). Clearly, continued research examining sex differences in ASD and transmission of QAT, as well as the reason(s) for the skewed sex-ratio, is needed.

This study has a number of unique strengths, including the ability to adjust for multiple potential confounders, use of cases and controls from a large existing cohort drawn from the general population, and the ability to examine family transmission in both affected and unaffected individuals in a relatively large sample, though some limitations should be noted. The NHS II population is not ethnically or racially diverse, so if impairments in social functioning are related to these factors, results may not generalize to all groups. Case status was primarily determined through maternal report. However, we validated diagnoses in a subgroup using the gold standard ADI-R, and results of both SRS scores and our ADI-R validation subgroup suggest a high degree of validity of maternal ASD report in this medically trained population of nurses. Residual confounding by divorce, which was collected in 2001 rather than at SRS administration, is possible; however, our analyses adjusting for available divorce status information suggested results were robust to this factor.

While reporter bias is another possible limitation, given that mothers completed SRS forms for both the father and the child, a number of factors both within our own data and from outside sources suggest this is unlikely to explain our results. First, our results demonstrated an equal proportion of mother and father elevated scores in controls. We also saw similar associations with risk of ASD according to both concordantly elevated parent scores and elevated father’s score, and the strongest increase in child scores when both parent scores were elevated. If reporter bias alone were accounting for findings, one might expect increases with father scores only. Second, results from other studies, in which multiple raters were used, suggest a high inter-rater reliability (r=0.75-0.919), particularly between mother and father SRS ratings of the child (r= 0.919; r=0.9233). In addition, a study examining potential models to explain patterns in family SRS data found evidence that a rater-bias model fit data the poorest, while an assortative mating model fit the data best1. Of note, this study found similar patterns of transmission of QAT to ours. Our data also suggested evidence of assortative mating, through the moderate spousal correlation.

The results of this study demonstrate the strong familiality of SRS scores, as well as, more broadly, of ASD and sub-clinical ASD traits, in both unaffected and affected families. Importantly, our work was conducted within a non-clinical group, with participants drawn from a well-established sample of the United States population. Our findings suggest that typical variation in parental social functioning and autistic traits is correlated in spousal pairs, predicts differences among offspring for these same traits, and at higher levels elevates risk for clinical autistic syndromes in children.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support: This work was supported by the following grants: National Institute of Health (NIH) grant CA50385; Autism Speaks grants 1788 and #2210; and the United States Army Medical Research and Material Command (USAMRMC) grant A-14917.

Footnotes

Author contributions: Dr. Lyall had full access to all the data in the study and takes full responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of data analysis. All authors contributed substantially to this work.

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: Dr. Constantino receives royalties from Western Psychological Services from the distribution of the SRS. All other authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Constantino JN, Todd RD. Intergenerational transmission of subthreshold autistic traits in the general population. Biol Psychiatry. 2005 Mar 15;57(6):655–660. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.De la Marche W, Noens I, Luts J, Scholte E, Van Huffel S, Steyaert J. Quantitative autism traits in first degree relatives: evidence for the broader autism phenotype in fathers, but not in mothers and siblings. Autism. 2012 May;16(3):247–260. doi: 10.1177/1362361311421776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Virkud YV, Todd RD, Abbacchi AM, Zhang Y, Constantino JN. Familial aggregation of quantitative autistic traits in multiplex versus simplex autism. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2009 Apr 5;150B(3):328–334. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schwichtenberg AJ, Young GS, Sigman M, Hutman T, Ozonoff S. Can family affectedness inform infant sibling outcomes of autism spectrum disorders? J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2010 Sep;51(9):1021–1030. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02267.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Constantino JN, Gruber C. Social Responsiveness Scale. Second Edition. Los Angeles, CA: Western Psychological Services; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Constantino JN, Gruber C. The Social Responsiveness Scale (SRS) Los Angeles, CA: Western Pyschological Services; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bolte S. Brief Report: the Social Responsiveness Scale for Adults (SRS-A): initial results in a German cohort. J Autism Dev Disord. 2012 Sep;42(9):1998–1999. doi: 10.1007/s10803-011-1424-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Constantino JN, Abbacchi AM, Lavesser PD, et al. Developmental course of autistic social impairment in males. Dev Psychopathol. 2009 Winter;21(1):127–138. doi: 10.1017/S095457940900008X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Constantino JN, Davis SA, Todd RD, et al. Validation of a brief quantitative measure of autistic traits: comparison of the social responsiveness scale with the autism diagnostic interview-revised. J Autism Dev Disord. 2003 Aug;33(4):427–433. doi: 10.1023/a:1025014929212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang J, Lee LC, Chen YS, Hsu JW. Assessing autistic traits in a Taiwan preschool population: cross-cultural validation of the Social Responsiveness Scale (SRS) J Autism Dev Disord. 2012 Nov;42(11):2450–2459. doi: 10.1007/s10803-012-1499-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kamio Y, Inada N, Koyama T. A Nationwide Survey on Quality of Life and Associated Factors of Adults With High-Functioning Autism Spectrum Disorders. Autism. 2012 Mar 7; doi: 10.1177/1362361312436848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Constantino JN, Zhang Y, Frasier T, Abbacchi AM, Law P. Sibling recurrence and the genetic epidemiology of autism. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167(111):1349–1356. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.09101470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Constantino JN, Todd RD. Autistic traits in the general population: a twin study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003 May;60(5):524–530. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.5.524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ho A, Todd RD, Constantino JN. Brief report: autistic traits in twins vs. non-twins--a preliminary study. J Autism Dev Disord. 2005 Feb;35(1):129–133. doi: 10.1007/s10803-004-1040-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hus V, Bishop S, Gotham K, Huerta M, Lord C. Factors influencing scores on the social responsiveness scale. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2013 Feb;54(2):216–224. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2012.02589.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Movsas TZ, Paneth N. The effect of gestational age on symptom severity in children with autism spectrum disorder. J Autism Dev Disord. 2012 Nov;42(11):2431–2439. doi: 10.1007/s10803-012-1501-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reiersen AM, Constantino JN, Volk HE, Todd RD. Autistic traits in a population-based ADHD twin sample. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2007 May;48(5):464–472. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01720.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wigham S, McConachie H, Tandos J, Le Couteur AS. The reliability and validity of the Social Responsiveness Scale in a UK general child population. Res Dev Disabil. 2012 May-Jun;33(3):944–950. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2011.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Robinson EB, Koenen KC, McCormick MC, et al. Evidence that autistic traits show the same etiology in the general population and at the quantitative extremes (5%, 2.5%, and 1%) Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011 Nov;68(11):1113–1121. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Constantino JN, Lajonchere C, Lutz M, Gray T, Abbacchi A, McKenna K, Singh D, Todd RD. Autistic social impairment in the siblings of children with prevasive developmental disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(2):294–296. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.2.294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aldridge FJ, Gibbs VM, Schmidhofer K, Williams M. Investigating the clinical usefulness of the Social Responsiveness Scale (SRS) in a tertiary level, autism spectrum disorder specific assessment clinic. J Autism Dev Disord. 2012 Feb;42(2):294–300. doi: 10.1007/s10803-011-1242-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Constantino JN, Gruber CP, Davis S, Hayes S, Passanante N, Przybeck T. The factor structure of autistic traits. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2004 May;45(4):719–726. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00266.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Solomon CG, Willett WC, Carey VJ, et al. A prospective study of pregravid determinants of gestational diabetes mellitus. JAMA. 1997 Oct 1;278(13):1078–1083. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lyall K, Pauls DL, Spiegelman D, Santangelo SL, Ascherio A. Fertility Therapies, Infertility and Autism Spectrum Disorders in the Nurses' Health Study II. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2012 Jul;26(4):361–372. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3016.2012.01294.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lord C, Rutter M, Le Couteur A. Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised: a revised version of a diagnostic interview for caregivers of individuals with possible pervasive developmental disorders. J Autism Dev Disord. 1994;24(5):659–685. doi: 10.1007/BF02172145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rubin D, Schenker N. Multiple imputation in health-care databases: an overview and some applications. Stat Med 19910731 DCOM- 19910731. 1991;10(4):585–598. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780100410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yang Y. Inc. SI, ed. Multiple Imputation for Missing Data: Concepts and New Development (Version 9.0) Rockville, MD: SAS Institute Inc; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hallmayer J, Cleveland S, Torres A, Phillips J, Cohen B, Torigoe T, Miller J, Fedele A, Collins J, Smith K, Lotspeich L, Croen LA, Ozonoff S, Lajonchere C, Grether JK, Risch N. Genetic Heritability and Shared Environmental Factors Among Twin Pairs With Autism. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011 Jul 4; doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.76. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Constantino JN, Todorov A, Hilton C, et al. Autism recurrence in half siblings: strong support for genetic mechanisms of transmission in ASD. Mol Psychiatry. 2013 Feb;18(2):137–138. doi: 10.1038/mp.2012.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gronborg TK, Schendel DE, Parner ET. Recurrence of Autism Spectrum Disorders in Full- and Half-Siblings and Trends Over Time: A Population-Based Cohort Study. JAMA Pediatr. 2013 Aug 19; doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.2259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Robinson EB, Lichtenstein P, Anckarsater H, Happe F, Ronald A. Examining and interpreting the female protective effect against autistic behavior. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013 Mar 26;110(13):5258–5262. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1211070110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Constantino JN, Charman T. Gender bias, female resilience, and the sex ratio in autism. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2012 Aug;51(8):756–758. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2012.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pearl A, Murray MJ, Smith LA, Arnold M. Assessing adolescent social competence using the Social Responsiveness Scale: Should we ask both parents or will just one do? Autism. 2012 Aug 21; doi: 10.1177/1362361312453349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.