Abstract

The aim was to determine the diagnostic performance of 3-dimensional virtual reality ultrasound (3D_VR_US) and conventional 2- and 3-dimensional ultrasound (2D/3D_US) for first-trimester detection of structural abnormalities. Forty-eight first trimester cases (gold standard available, 22 normal, 26 abnormal) were evaluated offline using both techniques by 5 experienced, blinded sonographers. In each case, we analyzed whether each organ category was correctly indicated as normal or abnormal and whether the specific diagnosis was correctly made. Sensitivity in terms of normal or abnormal was comparable for both techniques (P = .24). The general sensitivity for specific diagnoses was 62.6% using 3D_VR_US and 52.2% using 2D/3D_US (P = .075). The 3D_VR_US more often correctly diagnosed skeleton/limb malformations (36.7% vs 10%; P = .013). Mean evaluation time in 3D_VR_US was 4:24 minutes and in 2D/3D_US 2:53 minutes (P < .001). General diagnostic performance of 3D_VR_US and 2D/3D_US apparently is comparable. Malformations of skeleton and limbs are more often detected using 3D_VR_US. Evaluation time is longer in 3D_VR_US.

Keywords: structural abnormalities, first trimester, ultrasound, virtual reality, imaging technology

Introduction

There is an increasing interest in the detection of structural abnormalities in the first trimester of pregnancy, in particular in high-risk patients. Several factors have contributed to this shift of interest from the third and second trimesters of pregnancy to the first trimester. First, nuchal translucency measurements have become available as an effective screening tool for Down syndrome. As a result more structural abnormalities have been detected during the late first trimester. Second, ongoing technical development of ultrasound (US) equipment continues to improve visualization of first-trimester fetal anatomic structures.

The majority of structural abnormalities can now be detected during a first-trimester US scan.1–6 The reliability of first-trimester screening for structural abnormalities is still at debate. However, if structural abnormalities can be reliably diagnosed in the first trimester of pregnancy, this will improve earlier informed decision making.

Three-dimensional (3D) US is mainly used complementary to 2-dimensional (2D) US in specific cases where it may provide additional information.7 However, 3D_US is still presented by means of a 2D medium, which is unable to provide all information offered by the 3D data set.

In this study, we report on a new display technology called virtual reality (VR). This technology aims to further improve visualization by presenting 3D_US data as a hologram (3D_VR_US) in a 4-walled CAVE-like8 VR system in which investigators are surrounded by stereoscopic images (Figure 1C). A hologram is created by the V-Scope rendering application and polarized glasses enable the viewer to perceive depth and to interact with the 3D volume in an intuitive manner.9 In a research setting, the 3D_VR_US has already been successfully applied for determining various first-trimester reference values, and in individual cases of complex congenital malformations, 3D_VR_US supported the diagnosis by adding clinically relevant details.10–16

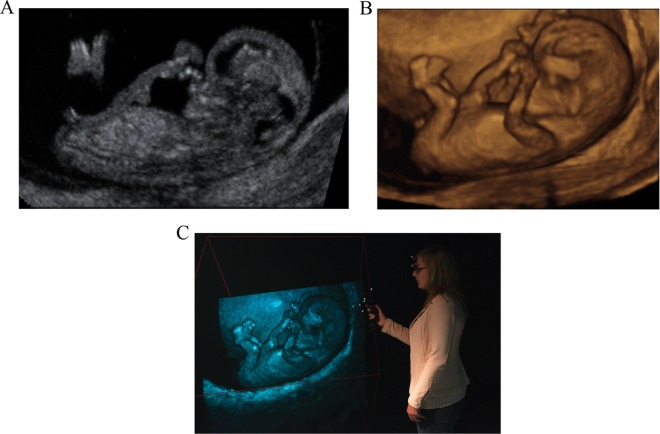

Figure 1.

A fetus of 10 + 3 weeks’ gestational age is visualized in (A) 2-dimensional ultrasound, (B) 3-dimensional (3D) ultrasound, and (C) the Barco I-Space 3D Virtual Reality system. The viewer is wearing polarized glasses and is holding the wireless joystick both equipped with a tracking system. Note that this 2-dimensional picture cannot express the 3-dimensionality of the original “hologram.”

Although clinicians rapidly adopted conventional 3D_US upon its introduction at the end of the 1990s without formal evaluation,7 this study aims to provide diagnostic evidence to support a similar decision on 3D_VR_US. The application is investigated for the use of first-trimester screening for structural abnormalities. Study outcomes are feasibility (in particular evaluation time) and diagnostic accuracy (sensitivity or detection rate) for both 2D/3D_US and 3D_VR_US compared to an independent gold standard.

Methods

In this comparative study, 48 pregnancies with known outcomes were assessed by 5 reviewers unknown to the cases. The 2 imaging techniques compared in this study are conventional 2D/3D_US (Figure 1A and B) and experimental 3D_VR_US (Figure 1C). The known outcome (gold standard) is based on all available information at the time of inclusion (midgestation US scan, outcome of the pregnancy, pathology report, etc). Twenty-four pregnancies were classified as abnormal due to structural congenital and/or other abnormalities and 24 pregnancies were classified as normal. Study outcome is limited to feasibility (in particular evaluation time) and diagnostic accuracy, both general and per organ system, if a structural abnormality is present. The study was conducted between April and September 2011.

Data Collection

Pregnancies were collected from an ongoing study, started in 2009, in which women are recruited for weekly US examinations between 6 and 12 weeks of gestational age (GA), and 2D/3D and 3D VR data are collected.13–15,17,18 This cohort aims to include uncomplicated pregnancies. Ultrasound examinations are performed transvaginal using a GE Voluson E8 system (GE Healthcare, Zipf, Austria) with a 9- to 12-MHz probe. This study is approved by the institutional medical ethical committee.

Selection of Used Cases and Controls

From the pregnancies of this cohort with available 2D/3D and 3D_VR data, we selected 24 abnormal pregnancies and, randomly, 24 normal pregnancies. Abnormality of pregnancy was determined at the time of inclusion by the clinical obstetrician in charge. Abnormal pregnancies were defined as cases with structural congenital abnormalities and/or maternal uterine abnormalities. All cases were selected on the availability of a postpartum diagnosis or a pathological investigation after termination of pregnancy. Only cases with reasonable image quality were included in the study. For this reason, images with poor image quality due to incompleteness of the 3D data set, an intermediate position of the uterus, or movement artifacts were excluded. We regarded this diagnosis (normal or abnormal with the specific abnormality) as the gold standard. The selected 24 abnormal cases were matched one to one to normal cases (birth of a child without congenital abnormalities, established in a similar way), with the same GA. The GA, based on the last menstrual period or conception date, ranged from 8 + 2 to 13 + 5 weeks.

Due to a database error, the assumed gold standard changed after reassessment: a twin pregnancy (classified as a normal singleton) and a pregnancy with a uterine myoma (classified as normal) were reclassified into the abnormal group. This led to a distribution of 22 normal and 26 abnormal pregnancies used for analysis. One or more abnormalities were present per case with a total of 54 structural abnormalities in our study population.

In Table 1, the number of included abnormalities per organ system is presented.

Table 1.

The Number of Included Abnormalities Per Organ System and Their Detection Rates (Sensitivity) Among the 5 Reviewers With Both Techniques.a

| Structural Abnormality | n | 3D_VR_US Detection Rate, n (%) | 2D/3D_US Detection Rate, n (%) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Uterus | 3 | 3/15 (20) | 2/15 (13.3) | 1.000 |

| Myoma | 1 | 1/5 | 1/5 | |

| Subseptus | 1 | 2/5 | 1/5 | |

| Asherman | 1 | 0/5 | 0/5 | |

| Twins | 6 | 25/30 (83.3) | 22/30 (73.3) | .248 |

| Bichorionic | 2 | 8/10 | 7/10 | |

| Monochorionic biamniotic | 2 | 7/10 | 7/10 | |

| Acardiac twin | 1 | 5/5 | 3/5 | |

| Conjoined twin | 1 | 5/5 | 5/5 | |

| Central nervous system | 8 | 17/40 (42.5) | 18/40 (45) | 1.000 |

| Exencephaly | 5 | 13/25 | 13/25 | |

| Holoprosencephaly | 1 | 2/5 | 5/5 | |

| Spina bifida | 2 | 2/10 | 0/10 | |

| Face and neck | 5 | 15/25 (60) | 12/25 (48) | .571 |

| Facial cleft | 1 | 5/5 | 2/5 | |

| Micro/retrognathia | 1 | 0/5 | 1/5 | |

| (Cystic) hygroma | 2 | 6/10 | 6/10 | |

| Increased nuchal tranlucency | 1 | 4/5 | 3/5 | |

| Hydrops | 9 | 34/45 (75.6) | 34/45 (75.6) | .250 |

| Hydrops fetalis | 8 | 29/40 | 29/40 | |

| Hydrothorax | 1 | 5/5 | 5/5 | |

| Thoracic | 1 | 2/5 (40) | 2/5 (40) | 1.000 |

| Ectopia cordis | 1 | 2/5 | 2/5 | |

| Digestive | 10 | 40/50 (80) | 32/50 (64) | .061 |

| Omphalocele | 2 | 10/10 | 8/10 | |

| Gastroschisis | 2 | 10/10 | 7/10 | |

| Large body wall defects | 1 | 3/5 | 4/5 | |

| External liver | 2 | 7/10 | 4/10 | |

| External stomach | 2 | 5/10 | 5/10 | |

| Intra-abdominal cyst | 1 | 5/5 | 5/5 | |

| Nephrourinary | 2 | 7/10 (70) | 6/10 (60) | 1.000 |

| Megacystis | 1 | 4/5 | 4/5 | |

| Ectopic bladder | 1 | 3/5 | 2/5 | |

| Skeletal/limbs | 6 | 11/30 (36.7) | 3/30 (10) | .013 |

| Skeletal dysplasia | 1 | 1/5 | 0/5 | |

| Radial aplasia | 1 | 2/5 | 1/5 | |

| Split hands/feet | 1 | 2/5 | 1/5 | |

| Polydactyly | 1 | 4/5 | 1/5 | |

| Scoliosis | 1 | 1/5 | 0/5 | |

| Kyphosis | 1 | 1/5 | 0/5 | |

| Other | 4 | 8/20 (40) | 6/20 (30) | 1.000 |

| Double yolk sac | 1 | 4/5 | 3/5 | |

| Umbilical cord cyst | 1 | 4/5 | 3/5 | |

| Short umbilical cord | 2 | 0/10 | 0/10 | |

| Total | 54 | 169/270 (62.6) | 141/270 (52.2) |

Abbreviations: 3D_VR_US, 3-dimensional virtual reality ultrasound; 2D/3D_US, 2- and 3-dimensional ultrasound.

aA total of 54 abnormalities were presented in 26 cases.

Reviewing Process

Five sonographers (AE, JC, EMS, MH, and KT), experienced in advanced US screening, the so-called “reviewers”, evaluated all 48 US volumes once with 2D/3D_US and once with 3D_VR_US. The clinical cases and images were unknown to the reviewers. The reviewers were also unaware of the distribution of normal and abnormal cases. Apart from GA, no other clinical information was provided.

All US volumes were evaluated offline with 2D/3D_US using the four-dimensional (4D) View software (version 9.1; GE Healthcare) and with 3D_VR_US using V-Scope software (Erasmus MC, Rotterdam, The Netherlands) in the BARCO I-Space.9 The reviewers reviewed the 48 cases once using 3D-VR_US and once using 2D/3D_US. To avoid recognition, a 4-week interval was used between the evaluations using the 2 techniques and as well the order of the cases differed for the 2 techniques. Findings of the reviewer using the 2 techniques are therefore treated as independent observations. The US volumes were anonymized and assigned an identification number, and the reviewers randomly started with either 2D/3D_US or 3D_VR_US. As both the I-Space (3D_VR_US) and the 4D-View software (2D/3D_US) were new to the reviewers, a brief training session preceded the study. In this training session, the reviewers were trained to translate, rotate, and magnify the volumes, to use the clipping plane, and to change the region of interest. No measurements were performed by the reviewers in this study.

During the study, the reviewer had a checklist available for every case containing all traceable structural abnormalities (n = 91) in the first trimester of pregnancy grouped by organ system. The reviewer scored for every category if an abnormality was present (or not) and if so which specific abnormality within the category was diagnosed. The time required for completion of the evaluation by the reviewer was recorded by the investigator (LB).

Finally, we offered a small survey to each reviewer to record subjective experience with 2D/3D-US and 3D_VR_US.

Analysis of Data

Correctness of classification (accuracy) was established in 2 ways. More permissive accuracy assumed the classification to be accurate if the right organ category was indicated as abnormal, whereas the specific diagnosis did not necessarily had to be correct. Strict accuracy assumed a specific diagnosis to be correct if the diagnosis corresponded with the gold standard. Standard diagnostic performance measures could be calculated for both types of accuracy: sensitivity, specificity, positive likelihood ratio (LR+), and negative likelihood ratio (LR−).

The statistical analysis was complex as there were 5 reviewers, 2 techniques, 2 levels of diagnosis (more permissive and strict accuracy), and 48 cases. The latter number limited the application of multi-level techniques or complex analysis of variance techniques. Instead, we applied exploratory analyses where the 5 reviewer judgements on 1 case or 1 abnormality were treated as 5 separate observations. Statistical testing and interpretation were conservative in this explorative context.

First we calculated the sensitivity for the detection of structural abnormalities comparing both techniques. A total of 54 individual abnormalities with 5 reviewers account for 270 detected abnormalities as a maximum. At this stage, we did not make a difference between cases and reviewers in order to get a rough comparison of sensitivity of 2D/3D_US and 3D_VR_US. Second, we computed the average sensitivity, specificity, and other diagnostic measures across cases at the reviewer level. These average performance measures were calculated using the more permissive accuracy and the strict accuracy, respectively. The more permissive approach has a total of 240 (48 cases × 5 reviewers) observations. The strict approach accounts for a total of 21 840 (48 cases × 5 reviewers × 91 possible abnormalities) observations.

Furthermore, the agreement among the reviewers in their final judgement and the evaluation time of both techniques were analyzed.

We used the dependent t test and the McNemar test for diagnostic performance comparisons and between technique comparisons and the independent t test for within technique comparisons (ie, evaluation time). We evaluated time differences over all cases and when omitting the first 5 or 10 cases to evaluate the possible effect of a learning curve in terms of time expenditure.

The survey results were used as additional qualitative information to support formal data analysis.

Results

The overall sensitivity of 3D_VR_US for detecting structural abnormalities was 62.6% (169 of 270) and was 52.2% (141 of 270) using 2D/3D_US, P = .075 (see Table 1 for a detailed comparison). Sensitivity of 3D_VR_US compared to 2D/3D_US was higher for small details like polydactyly (4 of 5 vs 1 of 5) and facial clefts (5 of 5 vs 2 of 5) and lower for holoprosencephaly (2 of 5 vs 5 of 5). Malformations of skeleton and limbs were significantly more often correctly diagnosed using 3D_VR_US (P = .013).

Table 2 displays data on the reliability of the 2 techniques to distinguish normal pregnancies from pregnancies with structural abnormalities. The average sensitivity, specificity, LR+, and LR− were not statistically different.

Table 2.

Test Characteristics of 3D_VR_US Versus 2D/3D_US in the Discernment of Abnormal (1 or More Structural Abnormalities) From Normal Cases.a

| (A) 3D_VR_US Reference | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Abnormal | Normal | Total | |

| Abnormal | 112 | 29 | 141 |

| Normal | 18 | 81 | 99 |

| Total | 130 | 110 | 240 |

| (B) 2D/3D_US Reference | |||

| Abnormal | Normal | Total | |

| Abnormal | 106 | 18 | 124 |

| Normal | 24 | 92 | 116 |

| Total | 130 | 110 | 240 |

| (C) | 3D_VR_US | 2D/3D_US | P |

| Sens (SD) | 86.2% (2.1) | 81.5% (6.3) | .235 |

| Spec (SD) | 73.6% (14.5) | 83.6% (16.6) | .051 |

| LR+ | 3.27 | 4.98 | .339 |

| LR− | 0.19 | 0.22 | .370 |

Abbreviations: 3D_VR_US, 3-dimensional virtual reality ultrasound; 2D/3D_US, 2- and 3-dimensional ultrasound; SD, standard deviation; Sens, sensitivity; Spec, specificity; LR+, positive likelihood ratio; LR−, negative likelihood ratio.

a(A) and (B) 2-by-2 tables combining all 5 reviewers of respectively 3D_VR_US and 2D/3D_US. (C) Average sensitivity, specificity, LR+, LR− of both techniques. (N = 48 × 5; 26 abnormal cases, 22 normal cases; all cases judged by 5 different reviewers with both techniques.)

Table 3 shows the same comparison but now analyzing the correctness of the specific diagnoses of structural abnormalities that were made. The average sensitivity, specificity, LR+, and LR− were not statistically different comparing the 2 techniques.

Table 3.

Test Characteristics of 3D_VR_US Versus 2D/3D_US in Making the Correct Diagnosis Per Case.a

| (A) 3D_VR_US Reference | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Structural abnormality | Normal | Total | |

| Structural abnormality | 169 | 76 | 245 |

| Normal | 101 | 21494 | 21595 |

| Total | 270 | 21570 | 21840 |

| (B) 2D/3D_US Reference | |||

| Abnormal | Normal | Total | |

| Abnormal | 141 | 64 | 205 |

| Normal | 129 | 21506 | 21635 |

| Total | 270 | 21570 | 21840 |

| (C) | 3D_VR_US | 2D/3D_US | P |

| Sens (SD) | 62.6% (8.4) | 52.2% (9.0) | .075 |

| Spec (SD) | 99.6% (0.22) | 99.7% (0.16) | .445 |

| LR+ | 177.6 | 176.0 | .851 |

| LR− | 0.375 | 0.479 | .074 |

Abbreviations: 3D_VR_US, 3-dimensional virtual reality ultrasound; 2D/3D_US, 2- and 3-dimensional ultrasound; SD, standard deviation; Sens, sensitivity; Spec, specificity; LR+, positive likelihood ratio; LR−, negative likelihood ratio.

a(A) and (B) 2-by-2 tables combining all 5 reviewers of respectively 3D_VR_US and 2D/3D_US. (C) Average sensitivity, specificity, LR+, LR− of both techniques. (N = 48 × 5 × 91; 48 cases [26 abnormal cases and 22 normal cases]; 91 possible first trimester structural abnormalities on score sheet; all cases judged by 5 different reviewers with both techniques.) Fifty-four different structural abnormalities were present in the 26 abnormal cases.

Furthermore, the agreement between the 5 reviewers was analyzed. The agreement in the distinction between normal and abnormal cases and the agreement on the specific diagnoses were studied separately. The agreement on classifying a case as “abnormal” was higher for 3D_VR_US, whereas 2D/3D_US had higher agreement in distinguishing the normal pregnancies (Supplementary Table 1). A better agreement between the reviewers was observed with 3D_VR_US as compared to 2D/3D_US in diagnosing malformations of the central nervous system and malformations of the skeleton and extremities (data available from the authors).

The reported mean time to evaluate a case using 3D_VR_US was 4:24 minutes and 2:53 minutes using 2D/3D_US (P < .001). More time was required with 3D_VR_US in the evaluation of normal pregnancies (+2:00 minutes, P < .001) as well as in pregnancies with structural abnormalities (+1:51 minutes, P < .001). If structural abnormalities were present, using 3D_VR_US, time expenditure was less as compared to time expenditure in normal cases (−1:05 minutes, P < .001). This difference was not seen with 2D/3D_US (−0:13 minutes, P = .152; Supplementary Table 2).

When excluding the first 5 or 10 cases per reviewer, the average evaluation time did not change, thereby excluding the possible effect of a learning curve in terms of time expenditure.

The subjective reviewers’ experience, as reported by the survey, showed that the required information was intuitively provided faster, and depth perception was better appreciated in 3D_VR_US. Operating 3D_VR_US was reported by the reviewers to be easy.

Discussion

The overall sensitivity for the detection of first-trimester structural abnormalities is high for both 3D_VR_US (62.6%) and 2D/3D_US (52.2%; P diff = .075). Thus, 3D_VR_US detected 10% more abnormalities, but this difference was not statistically significant. As available studies reported first-trimester detection rates (sensitivity) of structural abnormalities ranging from 18% to 84%,4,19–24 our study results are within the same range.

Although overall detection was quite similar, the sensitivity of malformations of the skeleton and extremities was significantly higher using 3D_VR_US. These malformations included, for example, polydactyly and radial aplasia. Holoprosencephaly was more often diagnosed using 2D/3D_US. It can be envisaged that the more spatial presentation of 3D_VR_US represents in particular a benefit in abnormalities at the exterior of the embryo, while the regular planes for brain evaluation using 2D/3D_US perform better for early detection of holoprosencephaly. This is also emphasized in the survey, where the reviewers stated that better depth perception was perceived using 3D_VR_US. The reviewers’ experience of faster information retrieval and easy-to-learn technique of 3D-VR_US further confirmed professional appreciation.

The higher yield and perhaps higher professional appreciation of 3D_VR_US have a price. The complete evaluation of a case requires on average more time for 3D_VR_US compared to 2D/3D_US, in particular in normal cases. In view of the larger amount of volume data in a hologram compared to 2D/3D_US, it requires more time to exclude abnormalities. We believe that more experience will turn this balance more to the advantage of 3D_VR_US. Remarkably, the reviewers stated in the questionnaire that the information they needed was provided faster using 3D_VR_US.

Some features of early pregnancy, like the position of the feet and the omphalocele, were scored as pathological while at this stage they are physiological. Before first trimester, screening of structural abnormalities will be effective these misunderstandings have to be elucidated. Other groups of assumed abnormalities showed considerable interreviewer differences with both techniques. These included malformations of the abdominal wall, the uterus, and the umbilical cord. Foremost, this can be explained by lack of experience in evaluation of early pregnancy. This study stresses the need for more basic information on the normal appearance of the early pregnancy. Other studies have shown that with increasing experience at first trimester, US screening the detection rates (sensitivity) of structural abnormalities increase.25,26

A lower detection rate than expected on beforehand was seen for some abnormalities. For example, the detection rate of ectopia cordis in this study was 40% for both techniques. This might be explained by the fact that heart action is not visualized in the offline, static, images that were used for the evaluation of cases. During real-time US, a detection rate of near 100% is most likely achieved. At this point, 4D (the 4th dimension being time) is not routinely obtained. These 4D data sets can however also be evaluated using VR, thereby overcoming the limitations of static images. Moreover, the detection rate of an increased nuchal fold was detected in 60% of the cases using 2D/3D_US. Detection rate would likely have been near 100% if the reviewers would have measured the nuchal fold in all cases. However, this would significantly prolong evaluation time and was therefore not performed in this study. Finally, it must be pointed out that 100% of twin pregnancies were detected in this study. The data in table reflect the percentage of twins that were correctly typed regarding chorionicity and amnionicity.

A limitation of the study is the retrospective design. We performed thorough blinding to account for this aspect. Furthermore, the retrospective design allows for comparison to a gold standard and therefore investigation of the validity of 3D_VR_US and 2D/3D_US, whereas a prospective study measures the agreement between 2 techniques. Second, due to the wide range and rarity of structural abnormalities, we choose to select our cases, instead of following a cohort, for efficiency reasons. This can be seen as another limitation of the study. A third limitation is the small number of studied cases. We deliberately aimed for a proof of concept study. Now, as we know that 3D_VR_US has the promise of improving the detection of first-trimester structural abnormalities, larger size studies are warranted to study the effect of 3D_VR_US in routine conditions. Agreeable, the BARCO I-Space does not lend itself for widespread dissemination as it is too large (requiring a separate room of at least 40 m2/400 ft2) and too expensive (approximately 500 000 USD). However, a desktop version of this 3D_VR_US system is developed, making this new and innovative technique broadly accessible to hospitals in the near future. A prototype is being evaluated at our department for use in daily clinical practice, and if successful, performance data like the ones shown in this article can be established overtime.

We conclude that in this proof-of-concept study, the diagnostic performance of 3D_VR_US and 2D/3D_US is statistically equal. A higher sensitivity was observed for abnormalities of skeleton and limbs in 3D_VR_US. Results suggest an additive value of 3D_VR_US in specific cases. As the time required for completion of the procedure was about 2 minutes longer for 3D_VR_US and reviewers subjectively reported better representation, the technique for now might be implemented under research conditions.

Footnotes

Authors’ Note: The procedures of the studied received ethics approval from the medical ethical committee of the Erasmus MC (METC Erasmus MC 2004-227).

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article: This research was financially supported by Erasmus Trustfonds, Erasmus Vriendenfonds, Meindert de Hoop Foundation, and Fonds NutsOhra.

Supplemental Material: The supplemental materials are available at http://rs.sagepub.com/supplemental.

References

- 1. Persico N, Moratalla J, Lombardi CM, Zidere V, Allan L, Nicolaides KH. Fetal echocardiography at 11-13 weeks by transabdominal high-frequency ultrasound. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2011;37(3):296–301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Chaoui R, Nicolaides KH. Detecting open spina bifida at the 11-13-week scan by assessing intracranial translucency and the posterior brain region: mid-sagittal or axial plane? Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2011;38(6):609–612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Syngelaki A, Chelemen T, Dagklis T, Allan L, Nicolaides KH. Challenges in the diagnosis of fetal non-chromosomal abnormalities at 11-13 weeks. Prenat Diagn. 2011;31(1):90–102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Whitlow BJ, Chatzipapas IK, Lazanakis ML, Kadir RA, Economides DL. The value of sonography in early pregnancy for the detection of fetal abnormalities in an unselected population. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1999;106(9):929–936 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Saltvedt S, Almstrom H, Kublickas M, Valentin L, Grunewald C. Detection of malformations in chromosomally normal fetuses by routine ultrasound at 12 or 18 weeks of gestation-a randomised controlled trial in 39,572 pregnancies. BJOG. 2006;113(6):664–674 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Nicolaides KH. A model for a new pyramid of prenatal care based on the 11 to 13 weeks’ assessment. Prenat Diagn. 2011;31(1):3–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Duckelmann AM, Kalache KD. Three-dimensional ultrasound in evaluating the fetus. Prenat Diagn. 2010;30(7):631–638 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cruz-Neira C, Sandin D, DeFanti T. Surround-screen projection-based virtual reality: the design and implementation of the CAVE (tm). In: Proceedings of the 20th Annual Conference on Computer Graphics and Interactive Techniques. New York: ACM Press; 1993 [Google Scholar]

- 9. Koning AH, Rousian M, Verwoerd-Dikkeboom CM, Goedknegt L, Steegers EA, van der Spek PJ. V-scope: design and implementation of an immersive and desktop virtual reality volume visualization system. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2009;142:136–138 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Verwoerd-Dikkeboom CM, Koning AH, Groenenberg IA, et al. Using virtual reality for evaluation of fetal ambiguous genitalia. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2008;32(4):510–514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Verwoerd Dikkeboom CM, van Heesch PN, Koning AH, Galjaard RJ, Exalto N, Steegers EA. Embryonic delay in growth and development related to confined placental trisomy 16 mosaicism, diagnosed by I-Space Virtual Reality. Fertil Steril. 2008;90(5):2017.e2019–2022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Groenenberg IA, Koning AH, Galjaard RJ, Steegers EA, Brezinka C, van der Spek PJ. A virtual reality rendition of a fetal meningomyelocele at 32 weeks of gestation. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2005;26(7):799–801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Rousian M, Koning AH, Hop WC, van der Spek PJ, Exalto N, Steegers EA. Gestational sac fluid volume measurements in virtual reality. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2011;38(5):524–529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Rousian M, Koning AH, van Oppenraaij RH, et al. An innovative virtual reality technique for automated human embryonic volume measurements. Hum Reprod. 2010;25(9):2210–2216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Rousian M, Verwoerd Dikkeboom CM, Koning AH, et al. Early pregnancy volume measurements: validation of ultrasound techniques and new perspectives. BJOG. 2009;116(2):278–285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Verwoerd-Dikkeboom CM, Koning AH, Hop WC, et al. Reliability of three-dimensional sonographic measurements in early pregnancy using virtual reality. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2008;32(7):910–916 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Verwoerd-Dikkeboom CM, Koning AH, Hop WC, van der Spek PJ, Exalto N, Steegers EA. Innovative virtual reality measurements for embryonic growth and development. Hum Reprod. 2010;25(6):1404–1410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Verwoerd-Dikkeboom CM, Koning AH, van der Spek PJ, Exalto N, Steegers EA. Embryonic staging using a 3D virtual reality system. Hum Reprod. 2008;23(7):1479–1484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hernadi L, Torocsik M. Screening for fetal anomalies in the 12th week of pregnancy by transvaginal sonography in an unselected population. Prenat Diagn. 1997;17(8):753–759 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. D’Ottavio G, Mandruzzato G, Meir YJ, et al. Comparisons of first and second trimester screening for fetal anomalies. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1998;847:200–209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Carvalho MH, Brizot ML, Lopes LM, Chiba CH, Miyadahira S, Zugaib M. Detection of fetal structural abnormalities at the 11-14 week ultrasound scan. Prenat Diagn. 2002;22(1):1–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Taipale P, Ammala M, Salonen R, Hiilesmaa V. Two-stage ultrasonography in screening for fetal anomalies at 13-14 and 18-22 weeks of gestation. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2004;83(12):1141–1146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Souka AP, Pilalis A, Kavalakis I, et al. Screening for major structural abnormalities at the 11- to 14-week ultrasound scan. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;194(2):393–396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Becker R, Wegner RD. Detailed screening for fetal anomalies and cardiac defects at the 11-13-week scan. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2006;27(6):613–618 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Levi S, Schaaps JP, De Havay P, Coulon R, Defoort P. End-result of routine ultrasound screening for congenital anomalies: the Belgian Multicentric Study 1984-92. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 1995;5(6):366–371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Taipale P, Ammala M, Salonen R, Hiilesmaa V. Learning curve in ultrasonographic screening for selected fetal structural anomalies in early pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;101(2):273–278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]