Abstract

Regenerative endodontics has gained much attention in the past decade because it offers an alternative approach in treating endodontically involved teeth. Instead of filling the canal space with artificial materials, it attempts to fill the canal with vital tissues. The objective of regeneration is to regain the tissue and restore its function to the original state. In terms of pulp regeneration, a clinical protocol that intends to reestablish pulp/dentin tissues in the canal space has been developed—termed revitalization or revascularization. Histologic studies from animal and human teeth receiving revitalization have shown that pulp regeneration is difficult to achieve. In tissue engineering, there are 2 approaches to regeneration tissues: cell based and cell free. The former involves transplanting exogenous cells into the host, and the latter does not. Revitalization belongs to the latter approach. A number of crucial concepts have not been well discussed, noted, or understood in the field of regenerative endodontics in terms of pulp/dentin regeneration: (1) critical size defect of dentin and pulp, (2) cell lineage commitment to odontoblasts, (3) regeneration vs. repair, and (4) hurdles of cell-based pulp regeneration for clinical applications. This review article elaborates on these missing concepts and analyzes them at their cellular and molecular levels, which will in part explain why the non-cell-based revitalization procedure is difficult to establish pulp/dentin regeneration. Although the cell-based approach has been proven to regenerate pulp/dentin, such an approach will face barriers—with the key hurdle being the shortage of the current good manufacturing practice facilities, discussed herein.

Keywords: stem cells, dentin, cell-based therapy, cell free, critical size defect, endodontics

Since the emergence of modern tissue engineering and regenerative medicine, regenerative endodontics have also gained attention (Murray et al., 2007). Researchers have applied the concept of tissue engineering to regenerative endodontics to test whether pulp/dentin can be regenerated in the root canal space (Nakashima and Huang, 2013). Concurrently, clinicians have been establishing and testing a clinical protocol—revitalization or revascularization procedures—to treat endodontically involved teeth, attempting to regenerate pulp/dentin (Lin et al., 2014). One key classification of the tissue regeneration approach is based on the use of exogenous cells or not—that is, cell based or cell free. In animal studies, the stem cell–based approach has demonstrated that pulp/dentin tissues can be regenerated in emptied root canal space with blood supply from only one end or from both ends (Huang et al., 2010; Iohara et al., 2011; Nakashima and Huang, 201; Rosa et al., 2013).

In contrast, the cell-free approach has not demonstrated the regeneration of pulp and dentin in canals in which the pulp tissue is completely removed (Wang et al., 2010; Lin et al., 2014). Why the revitalization protocol, a cell-free approach, has not been shown to induce the regeneration of pulp and dentin tissues may be related to the limitation of the protocol per se as well as the overexpectation of the protocol. This review article summarizes several concepts that have not been brought to the attention of or sufficiently discussed in this field: (1) critical size defect of dentin and pulp, (2) cell lineage commitment to odontoblasts, (3) regeneration vs. repair, and (4) hurdles of cell-based pulp regeneration for clinical applications. Some of them may explain why there has been difficulty regenerating pulp and dentin using the non-cell-based revitalization protocols. Although the stem cell–based approach has shown promise such that we can potentially de novo regenerate pulp/dentin orthotopically, many preparatory steps toward applying such a new technology into the clinic have not been in place. There are also inherent hurdles that may delay this progress that need to be overcome.

Critical Size Defect of Dentin and Pulp Complex

Critical size defect is an important concept when dealing with tissue regeneration; however, such a concept has not been discussed in pulp and dentin regeneration.

Definition of the “Critical Size Defect” Concept

Critical size defect for wound-healing studies on animals is defined for the defect of bone that, without introducing any supportive approaches, the defected area will not regenerate naturally during the lifetime of the animal (Takagi and Urist, 1982; Schmitz and Hollinger, 1986). To study bone healing, the frequently used standard test is the calvarial bone defect model. In mice, the critical size defect is 2 mm or larger in diameter (Cowan et al., 2004) and for rats, 8 mm (Spicer et al., 2012). One must create a tissue defect with a size that does not self-regenerate during the period of study so that it can be used as a negative control to compare the tissue regeneration using augmenting approaches, such as transplantation of stem cells. Most critical size defect studies in animal models are for bone regeneration, while only a few in the literature focus on defects of other tissues. For example, urethra critical size defect in a rabbit model is > 0.5 cm (Dorin et al., 2008); for nerve regeneration in rats, a 15-mm defect is critical size (Jiang et al., 2012); critical-size rabbit osteochondral defect can be a 5-mm-diameter full-thickness cylindrical defect (2-3 mm deep) (Liu et al., 2011).

Lack of Critical Size Defect Information for Dentin

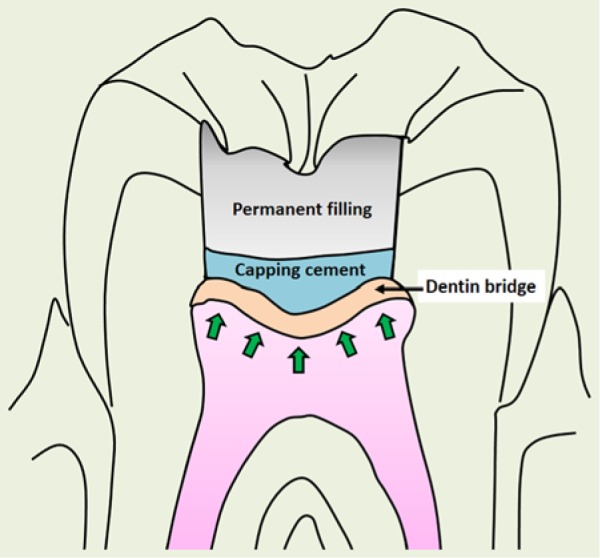

There has been no critical size defect in the field of dentin or pulp regeneration defined in an experimental model. Dentin regeneration is dependent on the healthy pulp. Direct pulp capping on normal pulp leads to dentin bridge (DB) formation. Clinically, the size of pulp exposure that decides whether a pulp capping or a complete root canal therapy is to be performed is not well defined. A recent study using a dog model to investigate dentin-pulp complex defect and regeneration was more inclined toward the testing of capping materials than defining the critical size defect (Yildirim et al., 2011). Recently, a new material—Biodentine (calcium silicate-based cement)—has been used for pulp capping and is able to stimulate DB formation in humans (Nowicka et al., 2013); however, critical size defect concept was not addressed or determined. Based on the potency of DB formation observed in germ-free study in rats (Kakehashi et al., 1965), conceptually, as long as the underlying pulp is healthy and germ-free, even if the entire pulp chamber roof dentin is lost, it may still be regenerated with DB (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Conceptual dentin bridge formation after the entire pulp chamber roof dentin is removed. Arrows indicate the replenishment of replacement odontoblasts.

Lack of Critical Size Defect Information for Pulp

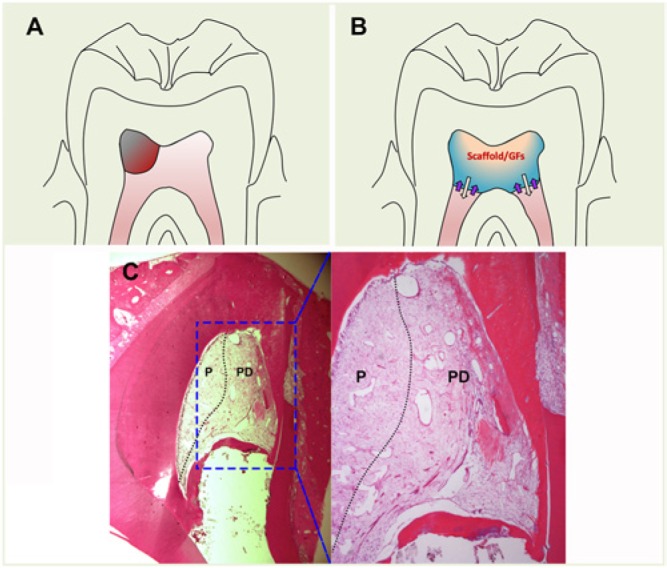

Clinically, it is unknown if pulp can regenerate if approximately 2 × 2 × 2 mm of pulp defect is created (Figure 2A). It is unlikely that the pulp can regenerate if the entire pulp in the pulp chamber space is removed (Figure 2B). One piece of evidence in a dog model study shed light on the capacity of pulp to regenerate if about half the pulp tissue is removed in the root canal system. As shown in Figure 2C, the remaining pulp does not help in the regeneration of the adjacent space where the pulp was removed and the lost pulp was replaced by periodontal-like tissues (Wang et al., 2010).

Figure 2.

Non-cell-based pulp regeneration. (A) Size of pulp defect (grayish red). (B) Hypothetic non-cell-based pulp regeneration in the pulp chamber space. Scaffold carrying growth factors (GFs) filled in the pulp chamber. White arrows indicate released GFs into the subjacent pulp in the canals. Purple arrows indicate migrating stem cells attracted by the GFs into the scaffold to regenerate pulp. (C) In a dog study, the immature tooth had pulpectomy, root canal infection, and disinfection and was filled with collagen for regeneration. Three months later, half the pulp tissue was found left behind in the canal and survived after infection and disinfection (left, indicated by P). The canal space in the right half was filled with periodontal-like tissues (PD) with cementum-like tissue ingrowth from the apical root surface cementum. Adapted from Wang et al. (2010) with permission. This figure is available in color online at http://jdr.sagepub.com.

Cell Lineage Commitment to Odontoblasts

Choosing either the cell-based or cell-free approach depends on several factors, and the size of the defect is a very important one, as discussed above. In terms of the cell-free approach for pulp and dentin regeneration, we need to discuss several aspects in turn.

Source of Stem Cells for Pulp/Dentin Regeneration

Traditionally, pulp tissue is sacrificed during the endodontic therapy to prevent further spread of infection. After the discovery of stem cells in apical papilla (SCAP), hope was generated that they may serve as an endogenous cell source to regenerate the entire pulp in the canal space even when the pulp is totally lost. In the case of loss of apical papilla, there has been a hope to attract stem cells in the periapical tissues or from a distant source to migrate into the canal space to regenerate pulp. To understand such a possibility, we must discuss 2 subjects.

Nonodontoblastic Lineage Differentiation into Odontoblastic Lineages

Using a cell-free approach, one must induce migration of adjacent or distant cells to occupy the canal space and differentiate into pulp cell and odontoblastic lineages. The adjacent cells would be those in the periodontal/periapical tissues. These already committed mesenchymal cells, such as cementoblasts and osteoblasts, are unlikely to convert into odontoblastic cells. Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) in these tissues may have the potential to fulfill this expected function. However, these MSCs are normally committed to differentiate into the tissue cells where they reside. Epigenetic regulatory mechanisms play a crucial role in defining the distinct lineage differences between dental follicle and dental pulp cells (Gopinathan et al., 2013). Periodontal ligament stem cells differentiate into cementogenic or osteogenic cells (Chadipiralla et al., 2010; Seo et al., 2004), whereas MSCs in the periapical alveolar bone differentiate into osteoblasts (Matsubara et al., 2005). One might consider that this commitment is determined by the local microenvironment that provides specific signaling to guide such differentiation. Once the cells are displaced in a different microenvironment, these MSCs might be converted into other lineages. Huo et al. (2010) induced dermal MSCs into odontogenic lineage by culturing these cells in the conditioned medium of embryonic tooth germ cells, and they found that the capacity of dermal MSCs, under such a stimulation to form ectopic dentin-like mineral tissue in vivo, is much weaker compared with dental pulp stem cells (DPSCs). Furthermore, no odontoblast marker dentin sialophosphoprotein can be detected. Under natural conditions, converting cementum- or bone-committed stem cells (e.g., periodontal ligament stem cells) into odontoblastic cells may be difficult. A recent report showed that by loading periodontal ligament stem cells onto the decellularized pulp extracullular matrix, these cells can express slightly increased odontoblast markers (Ravindran et al., 2014). However, whether these cells can produce dentin in vivo is yet to be tested. One point that should be emphasized is that there are no specific odontoblast markers; therefore, claiming the generation of new odontoblasts after pulp regeneration has to be carefully interpreted.

Nonodontogenic CD31– SP from bone marrow–derived MSCs (BMMSCs) or adipose tissue–derived stem cells can regenerate pulplike tissues, similar to using pulp CD31– SP cells, after being transplanted into the emptied root canal spaces in dog teeth (Ishizaka et al., 2012). This study also showed that the gene expression profiles among the regenerated pulplike tissues by these 3 different cell types are similar according to microarray analysis. This finding indicates that introducing the exogenous nonodontogenic type of stem cells into the root canal space may lead to pulp tissue regeneration. The environment in the root canal space may provide signals to guide these cells toward generating pulplike tissues.

Cell Homing

The term cell homing describes the engrafted hematopoietic cells homing to bone marrow where they normally reside (Lapidot et al., 2005) or homing to the injury site (Kavanagh and Kalia, 2011). The hematopoietic cells in bone marrow can also be mobilized and home to other organs (Hopman and Dipersio, 2014). One of the key factors that mobilizes these cells is granulocyte colony-stimulating factor. MSCs are also known to home to various organs, especially injured sites, by mobilization of the host endogenous MSCs or following systemic infusion of exogenous MSCs (Fukuda and Fujita, 2005; Karp and Leng Teo, 2009). This homing process is mediated by the SDF-1/CXCR4 axis, which directs the MSCs to particular sites. With this homing property, it has been thought that cells outside of pulp space can be attracted to home to the canal space and regenerate pulp and dentin.

For adjacent cells, such as SCAP or MSCs in periapical tissues, the issue lies in whether these cells can differentiate into pulp cells to make pulp and into odontoblasts to make dentin. SCAP are considered the source of odontoblasts to make root dentin (Sonoyama et al., 2008); therefore, endogenous SCAP may migrate into pulp space to regenerate pulp. However, MSCs in periapical tissues remain as their originally committed lineages after migration into pulp space, forming ectopic periodontal tissues in the space (Wang et al., 2010; Shimizu et al., 2013). These adjacent MSCs mainly have a perivascular location, some of which are considered pericytes (da Silva Meirelles et al., 2008).

As for MSCs in bone marrow that may be mobilized into the blood stream and attracted to pulp space, there are 2 issues to discuss. First, can BMMSCs home to pulp space and become odontoblast lineages? Second, will there be a sufficient number of cells homed to the pulp space to regenerate pulp and dentin? For the first question, a recent report may shed some light on the possibility. Zhou et al. (2011) utilized BMMSCs from GFP (green fluorescent protein) transgenic mice and transfused them via intravenous injection into irradiated wild-type mice. They found that these transplanted GFP+ BMMSCs migrated to and resided in pulp and periodontal ligament. Those GFP+ cells in the pulp exhibited similar properties to the native DPSCs. These findings suggest that if BMMSCs are to migrate to pulp, they have the potential to convert into DPSCs and become odontoblastic lineages. However, this experiment by Zhou et al. is highly contrived and artificial. If one attempts to attract endogenous circulating BMMSCs into the pulp space for pulp regeneration, the number may be too low to serve the purpose even if more of them are mobilized by granulocyte colony-stimulating factor treatments. Furthermore, the adjacent MSCs from the periapical tissues may migrate into the pulp space in greater number because of its proximity and compete for the tissue regeneration. This may explain why revitalization procedures tend to generate ectopic periodontal/periapical tissues in the canal space, not pulp and dentin. One report tested the concept of cell homing for pulp regeneration using the cell-free approach by applying a mixture of growth factors implanted in the root canal space, including VEGF-2, bFGF, PDGF, NGF, and BMP-7, to enhance cell recruitment, angiogenesis, reinnervation, and dentinogenesis. The authors found that pulplike tissue can be formed in an ectopic subcutaneous in vivo model (Kim et al., 2010). It remains to be tested whether in an orthotopic model such an approach can overcome the competition of the adjacent periodontally committed cells being chemoattracted by these factors and migrating into canal space which form periodontal tissues rather than pulp and dentin. Based on the literature, a conceptual theme is presented in Figure 3, depicting a cell-free approach for pulp regeneration and how it might work to allow pulp and dentin regeneration or how it might not work due to adjacent tissue–committed cell migration into the space.

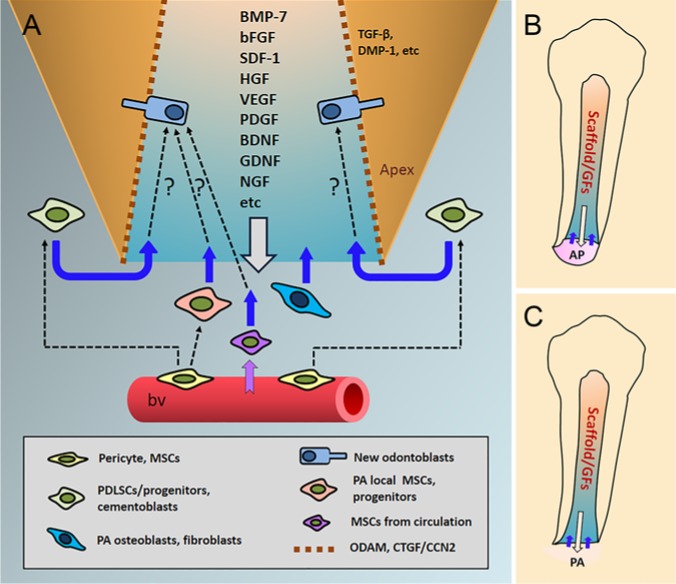

Figure 3.

A conceptual theme of a non-cell-based revitalization/regeneration procedure. (A) Root canal space is filled with a scaffolding material carrying growth factors (GFs), which are released into the adjacent tissues to induce stem/progenitor cell migration into the canal space and to guide the differentiation of the migrated cells into odontoblast lineages. The white arrow pointing down indicates the release of GFs into the apex. Purple and blue arrows pointing up are cell migration direction into the canal. Dashed arrows indicate (1) the perivascular pericytes at the local tissues, including periapical bone and periodontal ligament, giving rise to local MSCs and progenitors and (2) cells migrating into the canal space and transdifferentiating into new odontoblasts. (B) If the apical papilla (AP) is still present, cells in this tissue (e.g., stem cells in apical papilla) may be attracted into the canal space along with more distant cells from blood. (C) If AP is no longer present, periapical (PA) cells and distant cells from blood may be attracted into the canal space. Odontogenic ameloblast-associated protein and CTGF/CCN2 (connective tissue growth factor/CCN family 2) may be coated onto the dentin wall to facilitate odontoblast differentiation. TGF-β and DMP-1 embedded in dentin may be guiding odontoblast differentiation and new dentin generation. Theme concept based in part on several reports in the literature (Kim et al., 2010; Yang et al., 2010; Ishizaka et al., 2012; Muromachi et al., 2012; Ishizaka et al., 2013; Lin et al., 2014). BDNF, brain-derived neurotrophic factor; bFGF, basic fibroblast growth factor; BMP, bone morphogenetic protein; bv, blood vessel; DMP-1, dentin matrix acidic phosphoprotein 1; HGF, hepatocyte growth factor; GDNF, glia cell line–derived neurotrophic factor; NGF, nerve growth factor; SDF-1, stromal cell–derived factor 1; TGF-β, transforming growth factor β.

Quality of Regenerated Pulp and Dentin

When considering tissue regeneration, we normally expect the regenerated tissue to be identical to the original both structurally and functionally. However, based on their nature, some tissues—such as pulp and dentin complex—may be difficult to regenerate back to their original state.

Definition of Regenerated Pulp

Regenerated pulp should contain the following key features.

Formation of New Odontoblasts Lining against the Existing Dentin

Primary odontoblast differentiation requires the dental epithelium during tooth development. TGF-β family growth factors—particularly bone morphogenetic proteins (e.g., BMP-2, BMP-4, BMP-7)—play an essential role for this process (Jussila et al., 2013). However, odontoblast differentiation from DPSCs during pulp regeneration is a different process. New odontoblast-like cells in the regenerated pulp have been shown to form against the existing dentinal wall (Huang et al., 2010; Iohara et al., 2011; Ishizaka et al., 2012). The newly deposited dentin does not resemble the original dentin but is more similar to tertiary or reparative dentin (Figure 4). Studies on the mechanisms involved in the tertiary dentinogenesis revealed that matrix metalloprotease family and its endogenous inhibitors are upregulated with activation of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway in the pulp cells beneath the irritated dentin (Yoshioka et al., 2013). The formation process of tertiary dentin after pulp capping is what the pulp-engineering process is trying to duplicate. CTGF/CCN2 (connective tissue growth factor/CCN family 2) promotes mineralization of pulp cells and is highly expressed in new odontoblasts lining the reparative dentin, suggesting that CTGF/CCN2 may be involved in reparative dentinogenesis (Muromachi et al., 2012). Biodentine that has been used as pulp-capping cement induces TGF-β release from human pulp cells (Laurent et al., 2012), which may support new odontoblast differentiation and tertiary dentin formation. Odontogenic ameloblast–associated protein has been shown to induce normal tertiary dentin formation, whereas mineral trioxide aggregate induces excessive tertiary dentin after pulp capping (Yang et al., 2010). To achieve optimal pulp and dentin regeneration via a tissue-engineering process, applying knowledge gained from studying the molecular mechanisms involved in the tertiary dentinogenesis may help reach the goal.

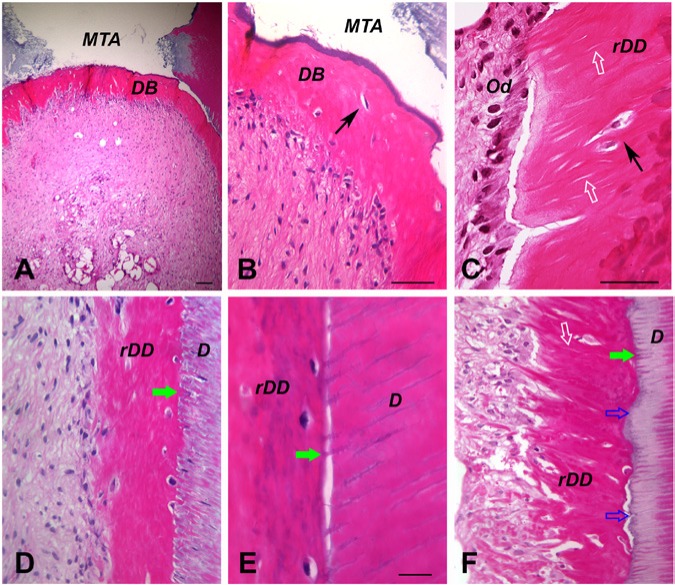

Figure 4.

Histologic analysis of regenerated dentin in root canal space. The emptied root canal space of human root fragments was filled with dental stem cells, and the constructs were transplanted in the subcutaneous space of SCID (severe combined immunodeficiency) mice for 3 to 4 mo. (A-B) Dentin bridge (DB) formation underneath the mineral trioxide aggregate (MTA) cement. (C-F) Regenerated dentin on dentin walls (rDD) using stem cells in apical papilla or dental pulp stem cells. D, dentin wall; black arrows, embedded cell in DB or rDD; white open arrows, dentinal tubules; green arrows, mineralized dentinal tubules; blue open arrows, nonmineralized dentinal tubules. Images are hematoxylin and eosin stain adapted with permission from Tissue Engineering, Part A, 2009, published by Mary Ann Liebert, Inc., New Rochelle, NY (Huang et al., 2010). Scale bars: A, 100 µm; B-D and F, 50 µm; E, 20 µm.

Newly Formed Vascularity and Reinnervation

Current available data indicated that vascularization can be achieved in regenerated pulp using stem cell–mediated approaches if the canal apical foramen is ≥ 0.6 mm (Nakashima and Huang, 2013). Qualitative comparison of the vascularity and the extracellular matrix of the regenerated pulp to the natural pulp has been reported to be similar (Iohara et al., 2011). It was thought that the use of angiogenic-inducing factors are needed to ensure or enhance pulp angiogenesis (Huang et al., 2008). However, it was found that pulp CD31– SP cells produce angiogenic factors (e.g., HGF, VEGF) and neurotropic factors (e.g., BDNF, GDNF, NGF) to support angiogenesis and reinnervation in the regenerated pulp (Ishizaka et al., 2013) and that these cells themselves are highly angiogenic and neurogenic (Iohara et al., 2008; Nakashima et al., 2009). Regenerated pulp has been found to be innervated with newly regenerated nerve fibers (Iohara et al., 2011) except that the specific innervation at the pulp-dentin complex has not been reported. Since the newly generated dentin does not appear to have well-organized dentinal tubules and is similar to reparative dentin, it is likely that regenerated pulp will not have the level of dentin sensitivity as that in the natural teeth.

Definition of Regenerated Dentin

So far, only cell-based, not non-cell-based, pulp/dentin regeneration has succeeded in generating pulp and new dentin in an orthotopic animal model. The regenerated dentin in this context is the formed DB or the newly deposited dentin onto the root canal wall. Currently, it has been shown that DB can form underneath the mineral trioxide aggregate filling after de novo pulp regeneration and that regenerated dentin can form along the canal walls (Huang et al., 2010; Nakashima and Huang, 2013). These 2 types of new dentin should be discussed separately. Regardless where the new dentin is deposited—either on mineral trioxide aggregate or on dentin—the newly formed dentin is structurally similar between DB and regenerated dentin on dentin walls (rDD) but is very different from the primary dentin, as shown in Figure 4.

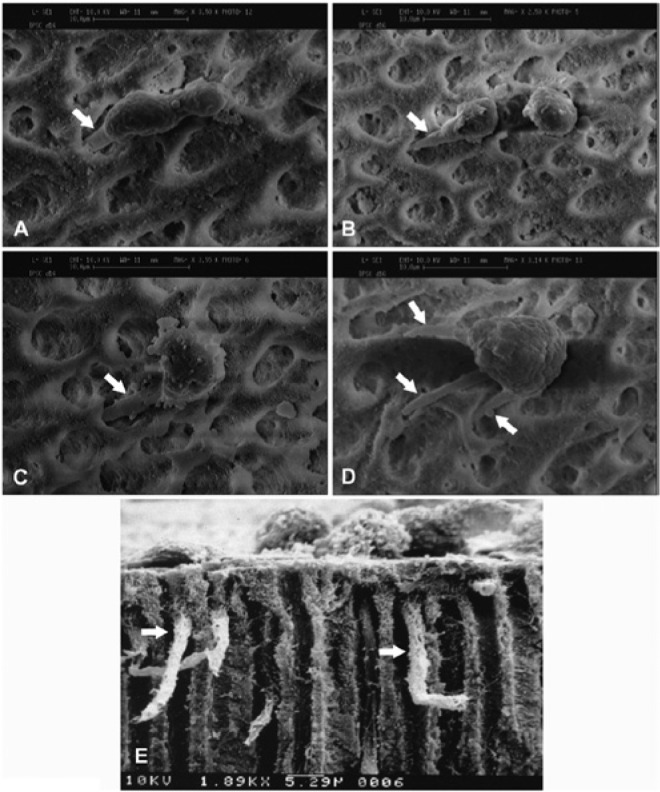

Why DB and rDD do not possess similar structures to the primary dentin may be due to the lack of developmental signaling from the ameloblasts and their membranes. The process of DB and rDD formation is also different. DB may be formed more similarly to primary dentin if the mineral trioxide aggregate is coated with a layer of dentin-forming signals. The newly differentiated odontoblast would lay down dentin while leaving behind its process for dentinal tubules to form. rDD, however, would go through a different process. A newly differentiated odontoblast would first attach onto the dentinal wall and then extend its process into a dentinal tubule (Figure 5). Since the dentin surrounding the newly inserted odontoblast process already exists, it would not need more dentin deposits in the tubular space. The new dentin should be formed only near the cell body, building the dentin toward the center of the canal space. However, based on our observation, it seems that most of the original dentinal tubules are further filled with new mineral deposits (Figure 4D, E, F). This is similar to what is observed in tertiary dentin formation on the existing dentin (Bouillaguet, 2004).

Figure 5.

Scanning electron microscope analysis of odontoblast-like cells on dentin surface in vitro. Cells were seeded onto dentin surface (dentin discs) with open dentinal tubules. Odontoblast-like cells subsequently formed and showed cellular processes extending into the dentinal tubules. (A-C) Each odontoblast-like cell derived from human dental pulp stem cells extends 1 process (arrow) into 1 dentinal tubule. (D) One odontoblast-like cell derived from a human dental pulp stem cell extends 3 observable cellular processes, and each process extends into 1 dentinal tubule (arrows). (E) Side view of the odontoblast-like cells, derived from mouse MDPC-23 cells (Hanks et al., 1998), extending the cellular processes into the dentinal tubules (arrows). Image sources: (A, B) adapted from Huang et al. (2006b) with permission; (C, D) from Huang et al. (2006a) with permission; (E) courtesy of Dr. Carl T. Hanks.

It seems difficult to produce newly formed dentin depositing onto the existing dentin seamlessly because of the nature of the regeneration process described. What appears to occur is that there are dentinal tubules in the newly formed dentin and that a significant number of odontoblasts are trapped and embedded in the newly formed osteoid dentin (Figure 4). During primary dentin development, each dentinal tubule is produced and occupied by 1 odontoblast. However, the newly differentiated odontoblasts may not each occupy 1 dentinal tubule; instead, there may be some dentinal tubules never occupied, and some odontoblasts may fill in more than 1 (formation of multiple cellular processes as shown in Figure 5D). With these situations, forming a highly organized new dentin is unlikely.

Pulp Repair or Regeneration?

As mentioned above, certain criteria are used to define tissue regeneration. If the lost tissue is replaced by scar or other type of tissues, it is not regeneration. Perhaps wound healing is a better term if not regeneration. In the field of regenerative endodontics, a considerable number of reports, including studies in dogs and clinical cases in humans, have shown that tissues were formed in the canal space after “regenerative endodontic” (i.e., non-cell-based) procedures (Lin et al., 2014). However, as long as it is not a cell-based approach, almost all reported studies or cases showed no pulp regeneration but repair—canal space filled with cementum-like, periodontal ligament–like tissue or some nonspecific fibrous tissues, and/or bone.

Issues on Preclinical Cell-Based Pulp Regeneration

To regenerate pulp de novo along with new dentin formation in the emptied root canal spaces is likely to require a cell-based approach. Establishing a clinical protocol using such an approach for pulp and dentin regeneration requires the following discussion.

Need of Affordable Current Good Manufacturing Practice Facilities

Current good manufacturing practice (cGMP) facilities are uncommon and the existing ones are mainly in pharmaceutical companies for developing drugs or non–live cell products. Those in research hospitals deal with hematopoietic cell transplants. Because of the high cost associated with the establishment and maintenance of a cGMP facility, few academic institutions have one. The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute sponsors 5 cGMP facilities across the United States, providing free service to investigators to mount clinical trials dealing with diseases within the scope of the institute. Currently, the cost to process MSCs from bone marrow alone may be as high as $20,000 per service because of the high overhead to create and maintain a cGMP facility. Thus, to initiate stem cell–based pulp tissue regeneration clinical trials, innovative designs for cGMP facilities to lower the cost are needed.

Source of Stem Cells

Whether the cell source is autologous or allogeneic, the processed cells may be cryopreserved before transplantation into the patient. Such treatments would require facilities where frozen cells are stored and ready for use when needed. A cGMP facility may include such a storage system. There are biomedical companies that have stem cell banking programs that can coordinate this type of service. Most cell therapies prefer the use of autologous cells to avoid transplant rejection, as immunosuppression treatment is cumbersome. MSCs, however, have special characteristics—immunosuppression, which can suppress immune rejection from the host and sustain (Yamaza et al., 2010; Zhao et al., 2010; Wang et al., 2013). Currently, there is no dental stem cell banking service available. Some small companies that deal with storage of extracted teeth preserve tissues only, not isolated cells. This has to do with the lack of affordable cGMP facilities that can provide cell isolation and storage services.

Check List before Cell-based Clinical Trials

Cells that are to be delivered into the host are considered drugs; therefore, their use is regulated by the Food and Drug Administration or the equivalent. GMP is needed to process cells for cell-based pulp and dentin regeneration. An approved cGMP facility contains clean rooms or spaces and follows Food and Drug Administration standards (see http://www.fda.gov/cosmetics/guidancecomplianceregulatoryinformation/goodmanufacturingpracticegmpguidelinesinspectionchecklist/default.htm). A clean room should have International Organization for Standardization level 7, and the clean space—where the cells will be directly exposed to, for example, tissue culture cabinet, should have at least level 5. At level 7, the maximum number of particles of size > 0.5 µm per cubic meter should be 352,000; at level 5, it should be 3,520 (Angtrakool, 2005). The particles in the room or space should also be tested for the presence of microorganisms. Expanded cells will be screened for the presence of pathogen and/or cytogenetic normalcy. While further investigation using large animal models is needed to establish reliable clinical protocols for pulp regeneration, clinical trials are also needed to test clinical safety and the reliability of the protocols. To mount a clinical trial, the following preparations should be in place: identification of a cGMP facility, establishment of standard operation protocols for processing clinical-grade stem cells, submission and approval of an investigational new drug application to the Food and Drug Administration, and approval of an institutional review board protocol.

Conclusions

The missing concepts discussed in this article may help establish an understanding of what issues we need to focus on and what hurdles we are facing regarding de novo pulp regeneration. If the size of the defect cannot be regenerated via a cell-based approach, the cell-free approach is less likely to do so. Non-cell-based therapy has yet to demonstrate such regeneration, whereas the cell-based approach already has done so, after the discovery of DPSCs in 2000 and the rigorous testing of the pulp regeneration using the concept of tissue engineering (Table). However, the hurdle of cell-based therapy is mainly the lack of available cGMP facilities. Additionally, establishment of a reliable clinical protocol requires further animal studies and testing of its safety via clinical trials.

Table.

Potential Treatment Outcomes by Different Regenerative Approaches

| Possible Outcomes |

||

|---|---|---|

| Defect | Cell-free | Cell-based |

| Dentina | ||

| Dentin only with healthy pulp | Dentin bridge formation | This approach may not be needed |

| Dentinb + pulp | ||

| Dentin + minimalc pulp loss | Dentin bridge formation, pulp regeneration—lack of data | Lack of data |

| Dentin + pulp chamber pulp loss | Dentin bridge formation, pulp regeneration—lack of data | Dentin- and pulp-like regeneration |

| Dentin + 1/3 to 1/2 of pulp loss in canal | Lack of data | Lack of data |

| Dentin + total pulp loss | Cementum-like bridge formation, periodontal-like tissue ingrowth | Dentin- and pulp-like regeneration |

Summary extrapolated in part from data presented in the literature (Kakehashi et al., 1965; Iohara et al., 2009; Huang et al., 2010; Wang et al., 2010; Iohara et al., 2011; Nowicka et al., 2013; Rosa et al., 2013; Shimizu et al., 2013).

Coronal dentin.

Partial loss of coronal dentin or entire loss of pulp chamber roof dentin (removed after access cavity).

For example, 2 × 2 × 2 mm.

Footnotes

This work was supported in part by grants from the National Institutes of Health (R01 DE019156; G.T.-J.H.) and by an Endodontic Research Grant from the American Association of Endodontists Foundation (G.T.-J.H.).

The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the authorship and/or publication of this article.

References

- Angtrakool P. (2005). International standard ISO 14644 cleanrooms and associated controlled environments. Washington, DC: Food and Drug Administration, pp. 1-84. URL accessed on 5/9/2014 at: http://drug.fda.moph.go.th/drug/zone_gmp/files/GMP2549_2/Aug2106/7.ISO14644.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Bouillaguet S. (2004). Biological risks of resin-based materials to the dentin-pulp complex. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med 15:47-60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chadipiralla K, Yochim JM, Bahuleyan B, Huang CY, Garcia-Godoy F, Murray PE, et al. (2010). Osteogenic differentiation of stem cells derived from human periodontal ligaments and pulp of human exfoliated deciduous teeth. Cell Tissue Res 340:323-333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowan CM, Shi YY, Aalami OO, Chou YF, Mari C, Thomas R, et al. (2004). Adipose-derived adult stromal cells heal critical-size mouse calvarial defects. Nat Biotechnol 22:560-567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- da Silva Meirelles L, Caplan AI, Nardi NB. (2008). In search of the in vivo identity of mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cells 26:2287-2299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorin RP, Pohl HG, De Filippo RE, Yoo JJ, Atala A. (2008). Tubularized urethral replacement with unseeded matrices: what is the maximum distance for normal tissue regeneration? World J Urol 26:323-326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuda K, Fujita J. (2005). Mesenchymal, but not hematopoietic, stem cells can be mobilized and differentiate into cardiomyocytes after myocardial infarction in mice. Kidney Int 68:1940-1943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gopinathan G, Kolokythas A, Luan X, Diekwisch TG. (2013). Epigenetic marks define the lineage and differentiation potential of two distinct neural crest-derived intermediate odontogenic progenitor populations. Stem Cells Dev 22:1763-1778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanks CT, Fang D, Sun Z, Edwards CA, Butler WT. (1998). Dentin-specific proteins in mdpc-23 cell line. Eur J Oral Sci 106(suppl 1):260-266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopman RK, Dipersio JF. (2014). Advances in stem cell mobilization. Blood Rev 28:31-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang GT, Shagramanova K, Chan SW. (2006a). Formation of odontoblast-like cells from cultured human dental pulp cells on dentin in vitro. J Endod 32:1066-1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang GT, Sonoyama W, Chen J, Park SH. (2006b). In vitro characterization of human dental pulp cells: various isolation methods and culturing environments. Cell Tissue Res 324:225-236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang GT, Sonoyama W, Liu Y, Liu H, Wang S, Shi S. (2008). The hidden treasure in apical papilla: the potential role in pulp/dentin regeneration and bioroot engineering. J Endod 34:645-651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang GT, Yamaza T, Shea LD, Djouad F, Kuhn NZ, Tuan RS, et al. (2010). Stem/progenitor cell–mediated de novo regeneration of dental pulp with newly deposited continuous layer of dentin in an in vivo model. Tissue Engineering Part A 16:605-615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huo N, Tang L, Yang Z, Qian H, Wang Y, Han C, et al. (2010). Differentiation of dermal multipotent cells into odontogenic lineage induced by embryonic and neonatal tooth germ cell-conditioned medium. Stem Cells Dev 19:93-104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iohara K, Zheng L, Wake H, Ito M, Nabekura J, Wakita H, et al. (2008). A novel stem cell source for vasculogenesis in ischemia: Subfraction of side population cells from dental pulp. Stem Cells 26:2408-2418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iohara K, Zheng L, Ito M, Ishizaka R, Nakamura H, Into T, et al. (2009). Regeneration of dental pulp after pulpotomy by transplantation of CD31(-)/CD146(-) side population cells from a canine tooth. Regen Med 4:377-385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iohara K, Imabayashi K, Ishizaka R, Watanabe A, Nabekura J, Ito M, et al. (2011). Complete pulp regeneration after pulpectomy by transplantation of CD105+ stem cells with stromal cell-derived factor-1. Tissue Eng Part A 17:1911-1920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishizaka R, Iohara K, Murakami M, Fukuta O, Nakashima M. (2012). Regeneration of dental pulp following pulpectomy by fractionated stem/progenitor cells from bone marrow and adipose tissue. Biomaterials 33:2109-2118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishizaka R, Hayashi Y, Iohara K, Sugiyama M, Murakami M, Yamamoto T, et al. (2013). Stimulation of angiogenesis, neurogenesis and regeneration by side population cells from dental pulp. Biomaterials 34:1888-1897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang X, Mi R, Hoke A, Chew SY. (2012). Nanofibrous nerve conduit-enhanced peripheral nerve regeneration. J Tissue Eng Regen Med 8:377-385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jussila M, Juuri E, Thesleff I. (2013). Tooth morphogenesis and renewal. In: Stem cells in craniofacial development and regeneration; Huang GT, Thesleff I, editors. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Kakehashi S, Stanley HR, Fitzgerald RJ. (1965). The effects of surgical exposures of dental pulps in germ-free and conventional laboratory rats. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 20:340-349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karp JM, Leng Teo GS. (2009). Mesenchymal stem cell homing: the devil is in the details. Cell Stem Cell 4:206-216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kavanagh DP, Kalia N. (2011). Hematopoietic stem cell homing to injured tissues. Stem Cell Rev 7:672-682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JY, Xin X, Moioli EK, Chung J, Lee CH, Chen M, et al. (2010). Regeneration of dental-pulp-like tissue by chemotaxis-induced cell homing. Tissue Eng Part A 16:3023-3031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lapidot T, Dar A, Kollet O. (2005). How do stem cells find their way home? Blood 106:1901-1910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laurent P, Camps J, About I. (2012). Biodentine(tm) induces tgf-beta1 release from human pulp cells and early dental pulp mineralization. Int Endod J 45:439-448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin LM, Ricucci D, Huang GT. (2014). Regeneration of the dentine-pulp complex with revitalization/revascularization therapy: challenges and hopes. Int Endod J 47:713-724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Jin X, Ma PX. (2011). Nanofibrous hollow microspheres self-assembled from star-shaped polymers as injectable cell carriers for knee repair. Nat Mater 10:398-406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsubara T, Suardita K, Ishii M, Sugiyama M, Igarashi A, Oda R, et al. (2005). Alveolar bone marrow as a cell source for regenerative medicine: differences between alveolar and iliac bone marrow stromal cells. J Bone Miner Res 20:399-409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muromachi K, Kamio N, Matsumoto T, Matsushima K. (2012). Role of CTGF/CCN2 in reparative dentinogenesis in human dental pulp. J Oral Sci 54:47-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray PE, Garcia-Godoy F, Hargreaves KM. (2007). Regenerative endodontics: a review of current status and a call for action. J Endod 33:377-390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakashima M, Iohara K, Sugiyama M. (2009). Human dental pulp stem cells with highly angiogenic and neurogenic potential for possible use in pulp regeneration. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev 20:435-440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakashima M, Huang GT. (2013). Pulp and dentin regeneration. In: Stem cells in craniofacial development and regeneration; Huang GT, Thesleff I, editors. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Nowicka A, Lipski M, Parafiniuk M, Sporniak-Tutak K, Lichota D, Kosierkiewicz A, et al. (2013). Response of human dental pulp capped with biodentine and mineral trioxide aggregate. J Endod 39:743-747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravindran S, Zhang Y, Huang CC, George A. (2014). Odontogenic induction of dental stem cells by extracellular matrix-inspired three-dimensional scaffold. Tissue Eng Part A 20:92-102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosa V, Zhang Z, Grande RH, Nor JE. (2013). Dental pulp tissue engineering in full-length human root canals. J Dent Res 92:970-975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitz JP, Hollinger JO. (1986). The critical size defect as an experimental model for craniomandibulofacial nonunions. Clin Orthop Relat Res 205:299-308. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seo BM, Miura M, Gronthos S, Bartold PM, Batouli S, Brahim J, et al. (2004). Investigation of multipotent postnatal stem cells from human periodontal ligament. Lancet 364:149-155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu E, Ricucci D, Albert J, Alobaid AS, Gibbs JL, Huang GT, et al. (2013). Clinical, radiographic, and histological observation of a human immature permanent tooth with chronic apical abscess after revitalization treatment. J Endod 39:1078-1083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonoyama W, Liu Y, Yamaza T, Tuan RS, Wang S, Shi S, et al. (2008). Characterization of the apical papilla and its residing stem cells from human immature permanent teeth: a pilot study. J Endod 34:166-171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spicer PP, Kretlow JD, Young S, Jansen JA, Kasper FK, Mikos AG. (2012). Evaluation of bone regeneration using the rat critical size calvarial defect. Nat Protocols 7:1918-1929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takagi K, Urist MR. (1982). The reaction of the dura to bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) in repair of skull defects. Ann Surg 196:100-109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Morsczeck C, Gronthos S, Shi S. (2013). Regulation and differentiation potential of dental mesenchymal stem cells. In: Stem cells in craniofacial development and regeneration; Huang GT, Thesleff I, editors. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Thibodeau B, Trope M, Lin LM, Huang GT. (2010). Histologic characterization of regenerated tissues in canal space after the revitalization/revascularization procedure of immature dog teeth with apical periodontitis. J Endod 36:56-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaza T, Kentaro A, Chen C, Liu Y, Shi Y, Gronthos S, et al. (2010). Immunomodulatory properties of stem cells from human exfoliated deciduous teeth. Stem Cell Res Ther 1:5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang IS, Lee DS, Park JT, Kim HJ, Son HH, Park JC. (2010). Tertiary dentin formation after direct pulp capping with odontogenic ameloblast-associated protein in rat teeth. J Endod 36:1956-1962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yildirim S, Can A, Arican M, Embree MC, Mao JJ. (2011). Characterization of dental pulp defect and repair in a canine model. Am J Dent 24:331-335. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshioka S, Takahashi Y, Abe M, Michikami I, Imazato S, Wakisaka S, et al. (2013). Activation of the wnt/beta-catenin pathway and tissue inhibitor of metalloprotease 1 during tertiary dentinogenesis. J Biochem 153:43-50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao S, Wehner R, Bornhauser M, Wassmuth R, Bachmann M, Schmitz M. (2010). Immunomodulatory properties of mesenchymal stromal cells and their therapeutic consequences for immune-mediated disorders. Stem Cells Dev 19:607-614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou J, Shi S, Shi Y, Xie H, Chen L, He Y, et al. (2011). Role of bone marrow-derived progenitor cells in the maintenance and regeneration of dental mesenchymal tissues. J Cell Physiol 226:2081-2090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]