Abstract

The use of manual-based interventions tends to improve client outcomes and promote replicability. With an increasingly strong link between funding and the use of empirically supported prevention and intervention programs, manual development and adaptation have become research priorities. As a result, researchers and scholars have generated guidelines for developing manuals from scratch, but there are no extant guidelines for adapting empirically supported, manualized prevention and intervention programs for use with new populations. Thus, this article proposes step-by-step guidelines for the manual adaptation process. It also describes two adaptations of an extensively researched anger management intervention to exemplify how an empirically supported program was systematically and efficiently adapted to achieve similar outcomes with vastly different populations in unique settings.

Keywords: anger management, intervention, manual adaptation, prevention, treatment

Manual-based intervention development has become a central component of clinical trial research.1 To obtain research funding, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) generally require operationally defined manual-based treatments (Rounsaville, Carroll, & Onken, 2001; Wilson, 1996), regardless of theoretical orientation. In addition, government and third-party payers have begun to tie funding to evidence-based treatment practices, which often use manualized interventions (Addis, 1997, 2002; Hayes, Barlow, & Nelson-Gray, 1999). With the increasingly strong link between funding and the use of empirically supported treatments, manual development and adaptation have become research priorities.

Controversy exists about the use of manualized treatments. Researchers, practitioners, and scholars have debated the utility of translating manual-based interventions from research to clinical practice. Critics have contested the ability of manualized treatments to address the nuances of clinical problems and diversity of clients, emphasized the overreliance on techniques, and questioned the flexibility of manuals to incorporate the benefits of clinical expertise (Addis & Krasnow, 2000; Carroll & Nuro, 2002; Kazdin, 2001; Kazdin & Kendall, 1998; Rounsaville et al., 2001). Proponents have emphasized that manualized programs systematize interventions, improve treatment fidelity, and facilitate well-designed treatment outcome research (Nezu & Nezu, 2008; Rounsaville et al., 2001). In addition, the use of manual-based treatments in clinical settings seems to improve client outcomes (Kazdin, 2001; Persons, Bostrom, & Bertagnolli, 1999). Nonetheless, researchers have stressed the importance of studying the generalizability of treatment manuals across different settings and populations (Kazdin, 2001; Seligman, 1995).

Despite controversy, well-defined prevention and intervention manuals are favored by NIH for research funding and, thus, are among the most well-researched treatments available (Wilson, 1996). Treatment settings looking to incorporate empirically supported interventions, therefore, rely heavily on manualized treatments. Treatment research and development guidelines have strongly suggested the use of operationally defined treatments that can be easily replicated across settings (Kazdin, 2002; Nezu & Nezu, 2008; Rounsaville et al., 2001). As such, intervention manuals are the most accepted and effective tool for disseminating empirically supported prevention and treatment programs (Addis, 1997; Chambless & Hollon, 1998).

With the increasing reliance on manualized interventions, researchers and scholars have generated guidelines for developing manuals from scratch (e.g., Carroll & Nuro, 2002; Onken, Blaine, & Battjes, 1997), but, to the best of our knowledge and research, there are no extant guidelines for adapting empirically supported, manualized treatments for use with new populations. Thus, this article will briefly review existing guidelines for manual development and will propose step-by-step guidelines for the manual adaptation process. Two adaptations of an empirically supported anger management treatment manual will be reviewed to exemplify the process.

CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK FOR MANUAL DEVELOPMENT

The following approach is grounded in Participatory Action Research (PAR) methodology, an approach that involves adapting empirically supported programs or strategies based on input from key stakeholders (e.g., community members, individuals from target treatment populations, prospective treatment providers) throughout the manual development process, pilot studies, and randomized controlled trials (RCT; Nastasi et al., 2000). In addition to generating an intervention that reflects the thoughts, feelings, and opinions of groups that will use the manual and resulting intervention, a primary goal of the PAR methodology is to generate relevant stakeholders’ investment in the treatment (Nastasi et al., 2000). Although theoretical orientation should guide targeted prevention and treatment development, the manual development process itself must be grounded in established methodologies (e.g., Carroll & Nuro, 2002; Rounsaville et al., 2001). PAR and the following step-wise approach provide a structure from which to develop treatment manuals across theoretical frameworks (e.g., psychodynamic, cognitive-behavioral).

Manual Development Through Adaptation

Carroll and Nuro (2002) proposed a three-stage model of manual development that involves the creation of a treatment and the evaluation of its efficacy and effectiveness. Briefly, Stage I involves the initial pilot work, including manual writing and an initial pilot study; Stage II involves the creation of a well-defined manual for use in randomized control studies and evaluation of the mechanisms of action; and Stage III involves creating detailed manuals and conducting multiple efficacy studies, as well as developing therapist training guidelines for transportability studies to real-life applications. Carroll and Nuro (2002) indicated that Stage III manuals should also contain information about the manual’s feasibility with and applicability to various clinical diagnoses and diverse populations.

These extant guidelines are useful for creating a well-designed, well-researched manual from scratch. Adapting existing empirically supported manualized treatments for use with new populations requires a similar systematic and thoughtful process. When population differences necessitate major modifications to a manual-based intervention, additional research must be conducted to maintain the treatment’s empirical integrity and value.

Development and Evaluation Steps When Adapting Manualized Treatments

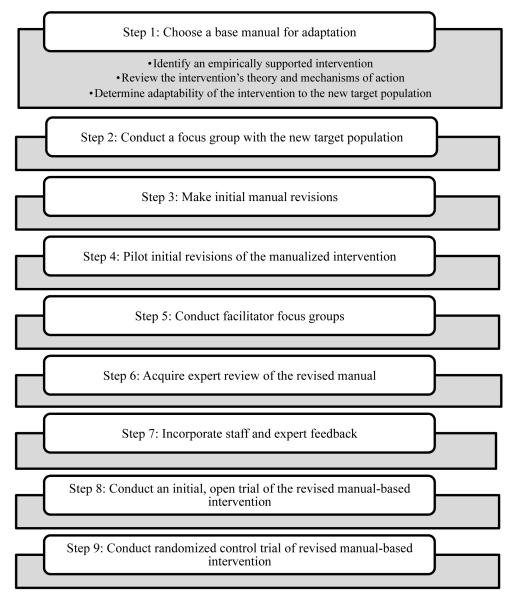

As with assessment development, manual adaptation can be considered a step-wise process. The proposed steps in Figure 1 can guide the revision of a manual-based treatment for use with a population that differs from the one for which the treatment was originally designed.

Figure 1.

Steps of the manual adaptation process.

These adaptation steps are consistent with Carroll and Nuro’s (2002) stage development process. Steps 1–5 parallel Carroll and Nuro (2002) suggested steps for Stage I manuals, and steps 6–8 parallel the developmental steps of Stage II and III manuals. The underlying theory and mechanisms of action that were empirically supported in the original manual remain constant through the adaptation process and should not be altered substantially. Previous empirical support may reduce the time required to proceed to the RCT of the adapted intervention, provided that careful attention is paid at each stage of the adaptation process to maintaining these core foundations of the original intervention manual.

Step 1: Choose a Base Manual for Adaptation

In order to adapt a manual for a specific population, an appropriate manual must be identified to serve as the base model. There are at least two approaches to adapting a manual for a new population: (a) begin with a well-researched intervention manual and then seek alternative, specific populations for which to adapt it (e.g., an empirically supported depression treatment for adults is adapted for use with children) or (b) begin by identifying a population with a clinical need and then find a manualized intervention that can be adapted for use with this population. The guidelines we present in this article were generated for the latter approach.

After identifying the population’s clinical need, a thorough literature search must be conducted with three primary goals: (a) identify whether an empirically supported intervention exists for the specific clinical target (e.g., anxiety, depression, anger management) and identify the intervention’s stage of research development and evaluation; (b) review the manual’s theoretical foundation and mechanisms of action for compatibility; and (c) determine whether the intervention is adaptable to the new population.

Identify an empirically supported intervention

As part of this first step, a literature review can help determine whether empirically supported, manual-based interventions exist to address the clinical area of interest. In the earliest phase, a broad literature search of the clinical issue should be conducted to identify manualized interventions for the clinical target (e.g., depression), regardless of setting (e.g., inpatient, outpatient, urban school, suburban community center) or population (e.g., teenage girls, gifted boys, adults suffering from grief, minority geriatric patients). The pluses and minuses of each identified intervention should be recorded to guide selection of the model manual and the adaptation process. In many instances, there may be a paucity of manualized interventions that closely match both the clinical area of interest and the population’s unique needs. Nonetheless, this wide search may yield interventions that have good research outcomes but require substantial adaptation to meet the needs of the target population. It may also allow researchers to better understand how adapting a manual for a population’s unique needs may fill a gap in the literature base.

After identifying potential model manuals, each manual should be evaluated for its empirical support; clearly, one wants to use, as a base, the most empirically promising extant manual, provided it is compatible with the adaptation goals. Ideally, an empirically supported intervention should demonstrate positive outcomes at multiple levels of research, including in a pilot study, in at least a few randomized controlled efficacy trials, and in effectiveness studies in applied settings (Carroll & Nuro, 2002). In addition, the outcome studies should have documented replicability through evaluation at multiple sites, and the intervention should have produced clear effects on the clinical area of interest (Kazdin, 2001). The outcome research also should include information about some of the potential moderators that may impact the likelihood of intervention success. Each intervention manual with empirically supported outcomes should, then, be thoroughly reviewed for its theoretical foundation and mechanisms of action.

Review the intervention’s theory and mechanisms of action

Each manual identified as a viable model for adaptation should be evaluated for consistency with the adaptation researchers’ goals, intervention approach, and proposed mechanisms of action.2 Although the ideal research process would involve dismantling studies to identify the mechanisms of action and moderators of treatment (Kazdin, 2002), this is not always feasible within the context of funding constraints, ethical treatment, and time limitations. Particularly, given the paucity of dismantling studies, the manualized intervention model should have strong theoretical underpinnings and identifiable, empirically supported mechanisms of action. Kazdin (2002) proposed some questions for evaluating therapy research that may be helpful to ask at this stage, such as the following:

What is the theoretical foundation of the manual?

What are the proposed components within the manual that contribute to therapeutic change?

What therapeutic processes are thought to mediate outcomes?

Determine adaptability of the intervention to the new target population

After identifying the most empirically supported manual with a theoretical basis that is consistent with the researchers’ goals and approach, the researchers must determine whether the manual should be adapted for use with the new population. This decision should be based on three overarching principles: (a) theoretical compatibility with the clinical population, (b) positive outcomes on the target behavior, and (c) implementation feasibility.

First, when determining theoretical compatibility, the researchers should consider whether the theoretical structure of the manualized intervention is appropriate for use with the target population. For example, adapting a cognitive restructuring–based anxiety treatment for adults for use with a low IQ population of elementary school children might be inappropriate; the children might be incapable of reframing negative, automatic thoughts into more coping-based, alternative thoughts. Second, when selecting the model manual, the intervention should, ideally, have demonstrated positive outcomes with a relatively similar population and have positive effects that are relevant to the new target population. For example, an anger management treatment with a school-based population that, in addition to successful reductions in anger, has produced significant reductions in substance use and truancy should translate well to a juvenile delinquency population. Third, when selecting the model manual, the researchers must consider the feasibility of implementing the manualized intervention with the new target population. For example, adapting an intensive, family-based autism intervention for use with autistic youth in a mainstream public school setting may be inappropriate—from a practical standpoint, the adapted treatment may not be able to produce the successful outcomes of the original, family-based treatment because of the school districts’ lack of resources, competing demands of the environment, and questions about whether teachers and school staff could make the same, intense commitments required of family members.

Should all three steps in Stage I be fulfilled, the researchers can begin adapting the base manual, with the goal of making it appropriate to and effective for the new target population while maintaining the integrity and value of the original intervention.

Step 2: Conduct a Focus Group With the New Target Population

Prior to initial manual adaptation, a focus group with the target population should be conducted to obtain feedback about the proposed content and structure of the intervention. Focus group size, information-gathering methodology, level of specificity requested, and abstractness of questions will depend on the target population. Clearly, the complexity and characteristics of questions should differ dramatically for a focus group of anxious college students and a focus group of young children with mental retardation. For more detailed information about constructing the format and content of focus groups, see Frankland and Bloor (1999) and Stewart, Shamdasani, and Rook (2007).

With some populations, researchers may want to seek the input of people close to the target population instead of, or in addition to, that of the target population. For instance, when adapting a treatment for preschoolers, it might be more appropriate to obtain feedback from parents or teachers than from the children. Similarly, if adapting a treatment for floridly psychotic adults in an inpatient facility, it might be helpful to obtain the input of significant others or support staff to supplement the feedback that would be obtained directly from individuals in the target population. Although researchers might be inclined to substitute the target population’s feedback with that of a higher-functioning proxy (e.g., significant other), most populations are able to provide some valuable feedback and their input should be sought. For instance, although floridly psychotic individuals may not have the insight or reasoning abilities to provide information about the content and structure of the proposed treatment, many would be able to identify current troubles they are having with staff or items and privileges that they would like to obtain as part of a reinforcement system.

Regardless of content, the focus group feedback should be collected in a confidential, structured format. The method of data collection may vary from observations to broad-based surveys to semi-structured interviews. The methodology should reflect the strengths of the population of interest and, when possible, multiple formats should be used.

When interpreting a focus group’s feedback and deciding how to incorporate input into the adapted intervention, the researchers need to consider how well the focus group participants represented the broader target population and the extent to which incorporating the feedback would help further the intervention goals. Focus group feedback should be a core component guiding intervention adaptation, but, clearly, it should not be the only guide. Previous research, theory, clinical experience with the population, and practical considerations (e.g., length of treatment, environment in which treatment will take place, resources available) should be major factors as well. Thus, researchers should thoroughly review the focus group’s feedback; carefully consider the degree to which feedback is consistent with research, theory, experience with the population, and practical considerations; and decide the degree to which each piece of feedback would help further the clinical goals of the intervention. Prior to collecting information from focus groups, researchers should establish processes and decision rules for addressing contradictory feedback (e.g., obtain guidance from an expert panel).

Step 3: Make Initial Manual Revisions

After carefully examining research and theory about the target population and area of clinical interest, and determining which focus group information should be incorporated, the researchers can begin the initial adaptation of the original empirically supported manual. This initial modification process may include changes to both the manual’s content and its structure (e.g., the number of sessions, length of sessions, degree of manualization for facilitators, language level for clients, amount of written material for clients).

Regarding content, there may be two primary areas for change: clinical content and procedural content. Clinical content adaptations involve changes to the actual clinical material included in the manual. For instance, an empirically supported treatment for adult-onset depression might involve cognitive restructuring and increasing pleasant activities; if adapting it for use with children with depression, it might also require incorporating a social skills training component, as youth suffering from long-term depression may withdraw to the extent that they fail to develop the appropriate social skills (Rao et al., 1995) needed to develop the friendships and social supports (Weissman et al., 1999) that can positively affect mood. Importantly, initial manual revisions must also incorporate advances in the clinical area of interest since the original manual was created.

Procedural content adaptations involve changes to the treatment administration, such as the specific activities and discussions used to convey the clinical content and facilitate clinical change. Such changes might be required as a result of discrepancies between the original and target populations in the levels of functioning, developmental stages, general interests, or types of experiences. For instance, minimizing the use of didactic techniques might be critical if the target population is children, individuals with attentional difficulties, or individuals with low intellectual functioning. In addition, when adapting homework assignments designed for adults for use with youth, the assignments might need to involve skills practice with parents, teachers, and friends instead of with spouses, children, bosses, and co-workers.

Differences in the restrictions and requirements of treatment locations might also require changes to the procedural content of the intervention. For instance, a social anxiety treatment with adults in the general population might involve graduated exposure to social situations (Bitran & Barlow, 2004). If adapting such a treatment for an incarcerated population, graduated exposure might not be feasible; the individual might have no choice but to sit in the middle of a large group of peers in a crowded cafeteria. Because the individual may be forced to physically experience a highly feared social situation early in treatment, greater emphasis may need to be placed on using coping techniques that moderate the levels of meaningful exposure to the event (e.g., using pleasant imagery to distance oneself from fully experiencing an anxiety-provoking event). Thus, intervention adaptation might require altering the details of the practice activities. Despite such changes to the procedural content, the researchers should pay particular attention to maintaining the mechanisms of action (i.e., in the above-mentioned example, exposure was the mechanism of action in the original intervention; exposure remained the mechanism of action for alleviating social anxiety in the revised treatment, even though the structure of the practice activity was revised).

Step 4: Pilot Initial Revisions of the Manualized Intervention

Researchers should pilot the initial revisions of the manualized intervention to examine the feasibility of the revised intervention with the target population, as well as to identify additional structural and content changes that might be needed. A pilot study’s design should vary according to both the feasibility of the study and the needs of the researchers (Kazdin, 2001). For example, a pilot study may be conducted as either a group design focusing on outcomes and effect sizes or as a single-case experimental design (Kazdin, 2001). Either type of pilot study design will allow researchers to modify the manual. When adapting a manual, regardless of the chosen design, researchers should use the pilot study to gather information and feedback from both participants and facilitators.

A primary goal of the pilot study should be to gather structured and meaningful participant and facilitator feedback about several important components of the first-draft manual. At a minimum, researchers should conduct knowledge checks to determine whether participants acquire and retain the material covered during each session and whether they retain this information throughout the duration of the intervention. Researchers should also seek participants’ thoughts about the acceptability and feasibility of the intervention. In addition to participant feedback, researchers should obtain facilitators’ feedback about the content, process, and feasibility of each intervention session and each activity. Questions designed to elicit content, process, and feasibility feedback from facilitators often parallel those asked of participants. The facilitator and participant feedback should be incorporated, wherever relevant and appropriate, into revisions of the first-draft manual. These revisions should result in a detailed second-draft manual that includes the necessary information for a Stage II manual, as described by Carroll and Nuro (2002).

Step 5: Conduct Facilitator Focus Group

After creating a second-draft of the adapted manual, researchers should conduct one or more focus groups with a sample of potential facilitators (i.e., providers who would conduct the intervention after it is tested and disseminated, such as school counselors, social workers, criminal justice staff, teachers, or outpatient treatment providers). Researchers may have conducted focus groups with targeted intervention facilitators prior to the initial manual adaptation, but feedback should be obtained again at this stage of development. Critics of manual-based interventions frequently cite the difficulty that facilitators, with varying levels of experience and expertise, have implementing them (Carroll & Nuro, 2002; Strupp & Anderson, 1997). In many cases, the facilitator requirements specified in an intervention manual cannot be met within the under-resourced systems for which such interventions are designed. Targeted facilitator focus groups provide a forum to reconcile these discrepancies early in the development process.

Furthermore, because pilot and outcome studies are frequently conducted by well-trained facilitators with dedicated time, it is important to gain feasibility information from prospective facilitators in the field. Such information may improve outcomes in the short-term and feasibility upon dissemination in the long-term. It also may narrow the common discrepancy between the large, positive outcomes of efficacy studies and the somewhat diminished outcomes of effectiveness studies (Kazdin, 2002).

Facilitator focus groups should be conducted in a confidential format with both structured and open-ended feedback opportunities. Researchers should introduce the focus group to potential facilitators by briefly reviewing the clinical area of interest, theoretical basis, manual development process, manual structure, and clinical content covered in the intervention. In addition, a copy of at least one session should be provided as an example of session flow, participant and facilitator instructions, and activities. The goal is not to obtain feedback on all details of the entire manual. Rather, it is to obtain feedback about the overall structure and content, ease of use and readability of the manual, acceptability of the manual to potential facilitators, and comparison of the manual with other relevant treatments already conducted by the potential facilitators with the target population.

Researchers should approach the facilitator focus groups broadly to cover many areas related to the feasibility of manual implementation. For example, if the revised manual-based intervention uses a point-based incentive system, the researchers may ask about its compatibility with the school’s or facility’s incentive system. Overall, quantitative and qualitative data should be collected from these focus groups. Following the expert review (see next section), the researchers should incorporate suggestions into another round of manual revisions and address frequent and/or notable concerns.

Step 6: Acquire Expert Review of the Revised Manual

Before incorporating the feedback obtained during the facilitator focus group, the second draft of the adapted manual also should be reviewed by a panel of experts with extensive experience with the clinical area of interest, the target population, and relevant cultural diversity. Panel members can review the manual individually and/or as a group. All members of this panel should review the manual in its entirety, as they should provide feedback on the overall structure of the manual, the overall therapeutic content of the intervention, anticipated feasibility for clients and facilitators, overall structure of the individual sessions, content of the individual sessions, and predicted outcomes. Quantitative and qualitative feedback should be sought to provide richer information to guide revisions.

Overall, feedback from the expert panel should be solicited using both open-ended and highly structured methods in a well-organized format that is easy to follow with the accompanying manual. Open-ended feedback should be sought, first, about the overall strengths and weaknesses of the intervention and its individual sessions; about any recommended content additions to or subtractions from the intervention and its individual sessions; and about the structure of the intervention, its individual sessions, and its activities. Researchers also should ask structured questions about each of these topics. Typically, session-based questions should parallel the order of presentation of information and activities in the manual to facilitate the feedback process for the expert reviewers. Targeted questions and rating scales that ask about each session’s content and activities can provide refined feedback about the value, comprehensibility, ease of use, and potential interest level for participants and facilitators. The expert panel’s review does not need to wait until the facilitator focus groups have been completed, as feedback from both sources will be incorporated into the next manual draft.

Step 7: Incorporate Staff and Expert Feedback

After obtaining feedback from potential facilitators and the expert panel, the researchers need to decide how best to evaluate and possibly incorporate feedback from diverse stakeholder groups. The researchers should develop guidelines for determining appropriate actions to address feedback. For instance, concerns and suggestions raised by two or more experts should be strongly considered for incorporation. Although such decision rules can help researchers deal with the feedback, they should be considered as guidelines only. Researchers should also recognize that feedback from one unique source or stakeholder group may be extremely important to incorporate if that individual or group is particularly knowledgeable or expert in a particular area of interest. For example, when constructing cartoon-based social-cognitive vignettes, the advice of youth who better understand the subtleties of facial expressions and body language within their own communities and cultural groups may be more valuable than that of expert reviewers. Nonetheless, although feedback from other sources is extraordinarily valuable, only the researchers are probably familiar enough with the intervention theory, the target population, and the practical constraints of the intervention to decide whether and how to incorporate each piece of feedback. When making these decisions, the research team should remember to maintain the theoretical mechanisms of action from the original manual and should consider the relevant literature on the target population for which the intervention is being adapted.

Step 8: Conduct an Initial, Open Trial of the Revised Manual-Based Intervention

After incorporating facilitator and expert panel feedback, the researchers should conduct an open trial of the newly revised manual. Similar to the pilot study, the initial open trial is designed to obtain participant and facilitator feedback, monitor participants’ compliance and facilitators’ adherence, and determine whether the manual needs any additional clarifications prior to the RCT. In addition, prior to the RCT, this open trial will provide facilitators with the opportunity to obtain clinical experience with the manual and researchers with the opportunity to obtain procedural experience with the study’s protocol, and with adherence, competence, and outcome measures (Kazdin, 2002; Nezu & Nezu, 2008).

The participant and facilitator feedback forms created for the earlier pilot study should be modified for consistency with revisions that were made to the manual since the pilot study. Researchers may seek feedback from participants about helpful and unhelpful components, acceptability of the intervention, comprehensibility of session material, interest in session activities, and ability to recall information after sessions. Facilitators should be asked about aspects for change or improvement; participant compliance with activities, including homework; flow of individual sessions’ content and structure; feasibility of session activities; overall flow of content across the manual; and ease of manual use for facilitators. Feedback from the initial trial participants and facilitators should be incorporated into the RCT manual draft.

At this stage of a manual, the theoretical underpinnings of the intervention should be clearly identified and communicated in the manual’s introduction (Carroll & Nuro, 2002). A cohesive intervention implementation plan and facilitators’ training strategies should be described as well. According to Carroll and Nuro (2002), by Stage II, the researchers should identify and include the following information in the introduction: the unique and essential elements of the intervention, the essential but nonunique elements, the nonessential elements, and counterproductive elements that may impede or harm intervention outcomes.

An accompanying facilitator training manual should define the minimum facilitator requirements (e.g., degree, experience) and the training that facilitators must complete (e.g., watch videotapes of mock sessions) before initiating the intervention. The facilitator-training manual should review the basic theory behind the intervention, discuss cultural sensitivity, address issues co-morbid with the target clinical issue, and specify the degree of manual flexibility. It should also review any techniques that cut across sessions that are not described in detail in the manual (e.g., use of praise as reinforcement for attention and performance).

Step 9: Conduct Randomized Controlled Trial of Revised Manual-Based Intervention

Once the RCT version of the manual is finalized, along with the facilitator-training manual, RCT procedures must be outlined in detail. Previous publications have described, in detail, appropriate methodology for RCTs (Kazdin, 2001; Nezu & Nezu, 2008). Therefore, we will not describe these methods in detail here. We will, instead, review the unique methodological issues associated with evaluating the efficacy and effectiveness of adapted manual-based intervention, including the selection of an appropriate control group and selection of appropriate and effective outcomes measures.

First, the ethical, financial, and practical constraints of research may limit the choices of control groups in an RCT. In theory, many potential control group options exist, including treatment as usual, attention placebo, no-treatment control, wait-list control, or an alternative treatment (for a discussion of the cost/benefit ratio of each type of control group, see Kazdin, 2001). The characteristics of both the target population and the clinical target will play a large role in determining the control group. For example, criminal justice–based research will make no-treatment and attention placebo controls more difficult due to practical and ethical concerns (i.e., treatment is mandated). Similarly, treatment for suicidal tendencies would rule out all no-treatment or delayed-treatment options.

Furthermore, although one might be inclined to use the original intervention as the control group, the original manualized intervention would probably be an inappropriate comparison group on theoretical and/or practical grounds. Because the original manual was deemed to need substantial revisions for the population of interest, how could the researchers responsibly use it with the new target population?

Regarding the selection of appropriate outcome measures, the selected RCT measures should have some consistency with those of the original intervention to compare results across studies. Ideally, at least some of the measures used to assess outcomes of the original intervention could be used to assess outcomes of the adapted intervention. Unfortunately, however, just as it might have been inappropriate to use the original intervention as a control group with the new target population, it might be inappropriate to use the original assessment measures. If the original measures cannot be used to evaluate the efficacy of the adapted intervention, measures of similar constructs should be used whenever appropriate. In particular, the RCT should include measures of the mechanisms of action that were thought to promote change with the original intervention to ensure that they were maintained in the adapted intervention. In addition, the researchers should certainly assess the unique treatment goals associated with the new target population.

Measuring adaptation success should largely depend on the ability to set clear, operationally defined goals and to successfully measure those goals. Researchers are encouraged to lay out, in detail, the definition of a successful manual adaptation. Symptom improvement, behavioral change, reduced interaction with the legal system, school retention, and clinically significant change all require clear standards of measure.

EXAMPLE MANUAL DEVELOPMENT AND ADAPTATIONS

Original Manualized Intervention: Coping Power Program

The Coping Power Program (Lochman & Wells, 2002a, 2002b, 2002c) is a multicomponent version of the Anger Coping Program (Lochman, Nelson, & Sims, 1981) and is designed for preadolescent and early adolescent youth with aggressive behavior problems. The Conduct Problems Program (CPP) child component (34 sessions) addresses the following: goal setting, emotion awareness, anger management training, organizational and study skills, perspective taking and attribution retraining, social problem solving, and coping with peer pressure and deviant peer involvement. The two over-arching goals for this cognitive-behavioral program are to assist children’s coping with the intense surge of physiological arousal and anger that they experience immediately after a provocation and to assist children in retrieving from memory possible competent strategies that they could use to resolve the problems that they are experiencing. The CPP also has a CPP Parent Component, which is designed to be integrated with the CPP child component. The 16 parent group sessions address parents’ use of social reinforcement and positive attention, their establishment of clear house rules, behavioral expectations and monitoring procedures, their use of a range of appropriate and effective discipline strategies, their family communication, their positive connections to school, and their stress management. Parents are informed of the skills that their children are working on in their sessions, and parents are encouraged to facilitate and reinforce children for their use of these new skills.

In an initial efficacy study (Lochman & Wells, 2004), 183 boys (61% African American; 39% Caucasian) who had high rates of teacher-rated aggression in fourth or fifth grades were randomly assigned to either a school-based CPP child component, to a combination of CPP child and parent components, or to an untreated control condition. In analyses of the 1-year follow-up effects of the program, CPP produced significant reductions in risks for self-reported delinquency, parent-reported substance use, and teacher-reported behavioral problems. The delinquency and substance use effects were most apparent for boys who received both intervention components, but the improvement in school behavior problems was primarily attributable to the CPP child component. Path analyses indicated that these intervention effects were at least partly mediated by intervention-produced changes in boys’ social-cognitive processes, schemas, and parenting processes (Lochman & Wells, 2002a).

Another study examined whether the effects of the Coping Power Program, offered as an indicated preventive intervention for high-risk aggressive children, could be enhanced by adding a universal prevention component. The sample consisted of 245 male (66%) and female (34%) aggressive fourth-grade students (78% African American; 20% Caucasian). Analyses of postintervention effects (Lochman & Wells, 2002b) indicated that the CPP intervention by itself produced reduced ratings of parent-rated proactive aggression, lower activity levels by children, better teacher-rated peer acceptance of target children, and increased parental supportiveness. The universal intervention augmented CPP effects by producing lower rates of self-reported substance use, lower teacher-rated aggression, and higher perceived social competence (Lochman & Wells, 2002b). At a 1-year follow-up, the Coping Power children had lower rates of delinquency, substance use, and teacher-rated aggression in school (Lochman & Wells, 2003), replicating the follow-up effects attained in the prior study.

Two randomized controlled trials have examined outcomes of an abbreviated version of Coping Power that can be implemented in one school year (with 24 child sessions and 10 parent sessions). In a study of 240 at-risk aggressive fifth graders that used propensity analyses and Complier-Average Causal Effect (CACE) modeling to control for dosage effects related to parent attendance, the program produced significant reductions in teacher-rated externalizing behaviors for children who had a caregiver attend at least one parent session (Lochman, Boxmeyer, Powell, Roth, & Windle, 2006). Coping Power has also been adapted effectively for use with aggressive deaf children (see Lochman et al., 2001), leading to improved problem-solving skills.

Coping Power has also been adapted for use with clinic populations. A briefer Dutch version of the CPP was evaluated in a study in which children with disruptive behavior disorders (N = 77) were randomly assigned to Coping Power or to clinic care-as-usual. Both conditions improved significantly on disruptiveness posttreatment and at a 6-month follow-up, but the Coping Power group had significantly greater reductions in overt aggression by posttreatment (van de Wiel et al., 2007). Coping Power clinicians had significantly less experience than care-as-usual therapists, indicating Coping Power’s cost-effectiveness (van de Wiel, Matthys, Cohen-Kettenis, & van Engeland, 2003). At a 4-year follow-up, Coping Power children had significantly lower marijuana and tobacco use than did care-as-usual children, indicating long-lasting, preventive effects of the intervention (Zonnevylle-Bender, Matthys, van de Wiel, & Lochman, 2007).

A dissemination study of the Coping Power Program was conducted with school counselors trained to implement Coping Power with high-risk aggressive fourth- and fifth-grade students (N = 531) in 57 elementary schools. The intensity of training provided to counselors had a notable impact on child outcomes. Significant improvements in child externalizing behavior only occurred when a more intensive form of training was provided (Lochman et al., 2009). Counselors with high levels of Agreeableness and Conscientiousness demonstrated best program implementation, and counselors who were high on cynicism and who were in schools with low levels of staff autonomy and high levels of managerial control had particularly poor quality of implementation (Lochman et al., in press).

One Adaptation of the Coping Power Program: Friend to Friend

The Friend to Friend Program (F2F) for urban African American relationally aggressive girls is a 20-session, 10-week program. The group is composed of relationally aggressive and prosocial third through fifth-grade girls.3 F2F was designed specifically for urban aggressive African American girls to best meet the needs of this high-risk group.

Step 1: Choose a Base Manual for Adaptation

Identify an empirically supported intervention

A systematic literature review was conducted in 2001 to identify school-based empirically supported programs for urban aggressive youth (see Leff, Power, Manz, Costigan, & Nabors, 2001). Thirty-two programs were identified in the literature search, and five programs were designated as being possibly efficacious (promising) based on criteria established by Chambless and Hollon (1998). Two of the possibly efficacious programs, CPP and Brain Power Program,4 were group interventions that had demonstrated positive prior results in studies with urban, physically aggressive minority youth. Further, both programs have a social-information processing (SIP) retraining emphasis in which aggressive youth are taught social problem-solving steps as a primary way in which to handle potential social conflicts. Given that none of the 32 programs identified in the systematic search was evaluated and/or effective for relationally aggressive girls, we chose to use the CPP as the starting point for the development of a program for urban African American aggressive girls.

Review the intervention’s theory and mechanisms of action

The CPP’s theory and mechanisms of action, SIP retraining, was in line with prior aggression research and was appropriate for use with the urban aggressive girls served by the F2F Program. In addition, Bronfenbrenner’s developmental ecological and systems (1986) theory also influenced the development and adaptation of F2F. The latter posits that children’s development and behavior are influenced not only by their cognitions and behaviors but also by their interactions with significant others within the relevant social environments (e.g., their peers, teachers, parents, and neighborhood influences).

Determine adaptability of the intervention to the new target population

The CPP was judged to be appropriate for adaptation because its general content, procedures, and behavioral management techniques appeared to be relevant for urban African American girls. Further, the idea of having participants in CPP participate in a video illustrating their use of social-cognitive strategies to prevent aggression was one that resonated greatly with feedback obtained from local stakeholders about the need to make strategies visual, appealing, and relevant for urban girls. In addition, the types of outcomes demonstrated by CPP were generally consistent with desired outcomes for urban aggressive girls.

Step 2: Conduct a Focus Group With the New Target Population

A PAR approach was utilized (see Leff, Costigan, & Power, 2004, or Nastasi et al., 2000, for a description of this approach) to integrate feedback from ongoing meetings between the intervention developers and different stakeholder groups. This approach helped the research team better understand how the CPP curriculum needed to be modified in order to be most relevant for urban relationally aggressive girls. For example, a group of fourth-grade girls from one urban elementary school met weekly with researchers to help them better understand how aggression develops and spreads among elementary age girls across unstructured school settings such as the playground during recess, the lunchroom, and the hallways. In addition, two teachers from different schools within the same school district met weekly with researchers over the course of 1–2 years to help develop the curriculum and homework assignments for F2F. Finally, the researchers were fortunate to have access to a number of playground and lunchroom supervisors from five different schools. These individuals were able to help the researchers understand what aggression among girls (and boys) looked like from their perspective and how this was manifested across unstructured school contexts (see Leff, Power, Costigan, & Manz, 2003; Leff et al., 2004).

Step 3: Make Initial Manual Revisions

Interestingly enough, while most of the CPP curriculum was viewed as being important and relevant for the target population of F2F, it was strongly suggested that a more active and visual teaching modality should be utilized. For instance, all stakeholder groups encouraged the interventionists to consider using cartoons and videotape illustrations of urban African American girls and to utilize as many active learning exercises as possible, such as role plays across sessions. Thus, much of the iterative development and adaptation of the F2F curriculum included working with girls, teachers, and community stakeholders in the development of these different modalities (Leff et al., 2007). As a result, F2F relies heavily on cartoon worksheets and homework assignment, video illustrations of key strategies, and role-play experiences (see Leff et al., 2007).

Step 4: Pilot Initial Revisions of the Manualized Intervention

Initial pilot testing of the F2F Program revealed a number of important aspects of the program that were used to fine-tune the program. First, the high acceptability of F2F for participants, teachers, and parents suggested that the program and culturally specific teaching modalities (cartoons, videos, and role plays) were well received. Second, teachers whose students participated in pilot testing of F2F strongly suggested that a classroom-based component be added to F2F in order to help them reinforce the program and its strategies with more students, girls and boys. Thus, eight classroom sessions were developed to largely mirror the content provided in the 20-session group intervention. The classroom component also is consistent with developmental-ecological systems theory in that high-risk girls who co-lead classroom sessions have a chance to demonstrate their more competent social skills and to thereby help to change the way in which they may be viewed and/or treated by their peers and teachers.

Step 5: Conduct Facilitator Focus Groups

Following initial piloting of the F2F group, extensive exit interviews with program facilitators and teaching partner co-facilitators were conducted. Recommendations included establishing consistent behavioral management strategies for facilitators to use, systematizing the facilitator and teacher partner trainings, continuing to develop additional cartoon illustrations for boys (for the classroom component), and fine-tuning several of the cartoon-based handouts and homework assignments.

Step 6: Acquire Expert Review of the Revised Manual

The F2F manual, cartoon handout and homework assignments, and integrity-monitoring criteria were reviewed by three experts within the field of urban African American youth development, relational aggression, and school-based program development, respectively. This step helped to ensure that all adaptations described were scientifically sound as well as culturally relevant.

Step 7: Incorporate Staff and Expert Feedback

Staff and expert feedback was carefully considered by the research team. All feedback was incorporated into a revised manual. Primary suggestions included ensuring that the primary content areas of each section were clearly demarcated. Further, staff and experts suggested that the manualized treatment build in flexibility for the diverse facilitators conducting the program. Thus, we wished to ensure that both a consistent presentation of core content areas was achieved while also allowing maximal flexibility in each facilitator’s being able to use his or her style or voice to achieve the session goals.

Step 8: Conduct an Initial, Open Trial of the Revised Manual-Based Intervention

A small-scale randomized study was conducted within two elementary schools to determine the acceptability of F2F and effect sizes for relevant outcome measures. Identified girls were randomly assigned to the F2F group or to a treatment-as-usual control group (e.g., referral to school counselor as needed). Results of this study suggest that the program is rated as quite acceptable by Stage II and/or III participating youth and teachers and has promise for decreasing hostile attributions of relational aggression, relationally and physically aggressive behaviors, and self-reported loneliness (Leff et al., 2009).

Step 9: Conduct Randomized Controlled Trial of Revised Manual-Based Intervention

A randomized controlled efficacy trial is currently in progress. The trial randomizes relationally aggressive girls to the F2F treatment arm or to an alternative education intervention called the Homework, Study Skills, and Organization (HSO) lunch group. The HSO group controls for all nonspecific factors of the treatment (e.g., time and attention of facilitators) while also providing a valuable academic intervention which may be useful to many aggressive youth.

Participants are assessed at three time points (i.e., pretest, posttest, and 9-month follow-up), using a combination of peer report measures, teacher report measures, self-report measures, and playground-based behavioral observations during lunch-recess.

The goal of the RCT is to observe changes in the targeted outcomes (e.g., reductions in relation and physical aggression, increases in social problem-solving, and decreases in loneliness). The trial will also address the possible mechanisms of action (e.g., different aspects of social problem solving). Similar to CCP, it is thought that a similar social-cognitive mechanism of action will be seen in the F2F Program.

Another Adaptation of CPP: The Juvenile Justice Anger Management Manual for Girls

The Juvenile Justice Anger Management (JJAM) Manual for Girls is a 16-session, 8-week program, with two 1.5-hour sessions per week. JJAM was designed to be gender-specific and culturally relevant to meet the needs of girls in the juvenile justice system.

Step 1: Choose a Base Manual for Adaptation

Identify an empirically supported intervention

A thorough search of the literature revealed a lack of empirically supported anger management interventions for female juvenile offenders. An expanded search, in 2001, of community- and school-based interventions for girls also resulted in no empirically supported treatment in this area. However, an expanded search of community- and school-based anger management intervention for boys identified CPP,5 a program that was empirically supported with both positive short- and long-term outcomes.

Review the intervention’s theory and mechanisms of action

The CPP’s theory and mechanisms of action that were described previously were consistent with the literature on childhood aggression and showed consistency with the desired outcomes of the current research. It was determined that these mechanisms of action could be maintained in an adapted manual for girls in a juvenile justice setting.

Determine adaptability of the intervention to the new target population

The CPP was determined to be adaptable for the new target population because of its: (a) age-appropriate session content, homework structure, behavioral management strategies, and interactive teaching techniques that could be modified for use with adolescent girls in the juvenile justice system and (b) positive short- and long-term outcomes (e.g., aggression reduction, decreases in substance use, improvements in behavioral control) that were considered relevant and critical to an efficacious anger management program for delinquent girls (Goldstein, Dovidio, Kalbeitzer, Weil, Strachan, 2007).

Step 2: Conduct a Focus Group With the New Target Population

A focus group was conducted with delinquent girls to obtain information about anger management and aggression reduction treatments in residential juvenile justice facilities. Focus group participants were surveyed about the extent and content of current anger management treatment programs at the juvenile justice facilities. The focus group also provided information about their anger triggers (e.g., substance use, bad-mouthing by others), relevant anger examples, and the positive and negative consequences of aggression in different settings (e.g., home, school, juvenile justice residential facility).

Step 3: Make Initial Manual Revisions

Despite the underlying theoretical similarities between CPP and JJAM in the approach to anger reduction, session content and activities were dramatically revised to meet the unique needs of delinquent girls in residential placement. Information was integrated from the focus group, as well as from the gender-specific juvenile justice literature. JJAM revisions were focused on addressing the unique needs of this population, including the high rates of anger, physical aggression, and relational aggression; high rates of mental illness (e.g., anxiety, depression, substance abuse); low IQ scores; poor academic abilities; and lack of adaptive social support systems.

Step 4: Pilot Initial Revisions of the Manualized Intervention

The adapted manual was piloted with a small sample of female juvenile offenders. The two main goals of the pilot study were to evaluate the feasibility of implementing JJAM and to solicit feedback from the participants and facilitators about the treatment, such as activities they liked and did not like, their abilities to understand the concepts that were taught, the acceptability of teaching methods, and any other unforeseen problems. See Goldstein et al. (2007) for a thorough review of the pilot study and its findings.

Step 5: Conduct Facilitator Focus Groups

Following the PAR methodology that involves community stakeholders in treatment development research, input was sought from staff at two juvenile justice facilities on the second draft of the adapted manual. To obtain a diversity of approaches and opinions about the ways in which to optimize JJAM’s effects, one focus group was held at a large postadjudication facility in a rural area; the other was held at a small postadjudication group home in an urban area. Staff members were asked about their impressions of the skills required of strong group leaders (e.g., ability to positively redirect, patience) and about JJAM’s content, structure, ease of use, and readability.

Step 6: Acquire Expert Review of the Revised Manual

The JJAM manual was then reviewed by the mentors and consultants on a National Institute of Mental Health early career award, each of whom had expertise in at least one area relevant to the development of JJAM (e.g., anger management, juvenile justice, treatment development, interventions with women and multicultural groups).

Step 7: Incorporate Staff and Expert Feedback

Staff and expert feedback was reviewed by researchers and incorporated into a revised manual. Both staff and experts provided feedback on the content of the treatment, reflected on the appropriateness of treatment activities for the population, offered suggestions for improvement, and provided thoughts about the degrees to which the levels of detail, flexibility, and clarity would be appropriate for use with female juvenile offenders and by staff at juvenile justice facilities.

Step 8: Conduct an Initial, Open Trial of the Revised Manual-Based Intervention

Using PAR methodology, an initial trial with the target population was conducted to evaluate the feasibility, acceptability, and appropriateness of JJAM by obtaining feedback from group facilitators and participants. Information was sought about participants’ attendance, participation, and compliance with homework; participants’ understanding of JJAM content and interest in JJAM activities; and cultural relevance of JJAM lessons.

Step 9: Conduct Randomized Controlled Trial of Revised Manual-Based Intervention

The randomized controlled efficacy trial, currently in progress, compares (a) JJAM plus treatment as usual to (b) a treatment-as-usual control condition. Participants are randomly assigned to condition. Participants are assessed at three time points (pretest, posttest, and 6-month follow-up), using a combination of structured interviews, self-report measures, peer-nomination measures, rating scales, and record reviews.

The goal of the RCT is to observe changes in the targeted outcomes (e.g., reductions in recidivism and aggressive behavior), as well as to evaluate the mechanisms of action (e.g., emotion regulation, social problem solving). Consistent with the adaptation process, it is anticipated that not only will there be reductions in anger and aggressive behaviors, but also the mechanisms of action identified in the CPP will have been maintained in the development of JJAM.

CONCLUSION

With the establishment of manual-based interventions as core features of clinical trial research, and with funding opportunities often linked to the use of such interventions, researchers and clinicians need manualized prevention and treatment programs with increasing frequency. Nonetheless, significant gaps remain in the availability of empirically supported, manualized interventions, particularly for specialized populations. Recognizing the wide gap between the strain of limited resources and the importance of an emic approach, this article presented a step-wise approach to manual adaptation that maintains fidelity to the original intervention and incorporates important cultural, gender, and other population-specific factors in an effort to improve applicability and outcomes.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The research for the Juvenile Justice Anger Management (JJAM) Treatment for Girls was supported by a grant from the National Institute of Mental Health. The research for the Friend to Friend (F2F) Program for Urban Relationally Aggressive Girls was supported by a grant from the National Institute of Mental Health (R01MH075787). Research on the Coping Power Program has been supported by grants from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (R01 DA023156; R41 DA022184; R01 DA16135; R0108453), the National Institute of Mental Health (P30 MH066247), the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (R49 CCR418569), and the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (KD1 SP08633; UR6 5907956).

NOTES

In this article, “intervention” refers broadly to prevention, intervention, and treatment programs.

A mechanism of action, or mediator, is the specific action (e.g., reducing fear of fear) by which a treatment or treatment technique (e.g., exposure) changes the targeted symptom(s) (e.g., increased heart rate; Baron & Kenny, 1986).

A combination of aggressive youth and positive role models is used given prior research suggesting groups composed solely of aggressive youth may not be as effective in reducing aggression (Dishion, McCord, & Poulin, 1999). Typically, about 75% of F2F group participants are relationally aggressive as compared to prosocial role models.

The initial search actually identified the Anger Coping Program (Lochman, Fitzgerald, & Whidby, 1999), an earlier version of the CPP, on which F2F was ultimately based. However, for ease of communication, the treatment name, CPP, will be used throughout this section. Further, a second program, the Brain Power Program (Hudley & Graham, 1993) was also heavily influential in the development of F2F. However, for the purpose of illustration in this article, we will primarily discuss the influence of CPP.

The initial search actually identified the Anger Coping Program (Lochman et al., 1999), an earlier version of the CPP, on which JJAM was ultimately based. However, for ease of communication, the treatment name, CPP, will be used throughout this section.

REFERENCES

- Addis ME. Evaluating the treatment manual as a means of disseminating empirically validated psychotherapies. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 1997;4(1):1–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2850.1997.tb00094. [Google Scholar]

- Addis ME. Methods for disseminating research products and increasing evidence-based practice: Promises, obstacles, and future directions. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2002;9(4):367–378. doi: 10.1093/clipsy.9.4.367. [Google Scholar]

- Addis ME, Krasnow AD. A national survey of practicing psychologists’ attitudes toward psychotherapy treatment manuals. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2000;68(2):331–339. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.68.2.331. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.68.2.331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;51(6):1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bitran S, Barlow DH. Etiology and treatment of social anxiety: A commentary. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2004;60(8):881–886. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20045. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U. Ecology of the family as a context for human development: Research perspectives. Developmental Psychology. 1986;22(6):723–742. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.22.6.723. [Google Scholar]

- Carroll KM, Nuro KF. One size cannot fit all: A stage model for psychotherapy manual development. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2002;9(4):396–406. doi: 10.1093/clipsy.9.4.396. [Google Scholar]

- Chambless DL, Hollon SD. Defining empirically supported therapies. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1998;66(1):7–18. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.66.1.7. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.66.1.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, McCord J, Poulin F. When interventions harm: Peer groups and problem behavior. American Psychologist. 1999;54(9):755–764. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.54.9.755. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.54.9.755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frankland J, Bloor M. Some issues arising in the systematic analysis of focus group materials. Sage Publications Ltd.; Thousand Oaks, CA: 1999. doi:10.4135/9781849208857. [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein NE, Dovidio A, Kalbeitzer R, Weil J, Strachan M. Anger management for female juvenile offenders: Results of a pilot study. Journal of Forensic Psychology Practice. 2007;7(2):1–28. doi: 10.1300/J158v07n02_01. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes SC, Barlow DH, Nelson-Gray RO. The scientist practitioner: Research and accountability in the age of managed care. 2nd ed Allyn & Bacon; Needham Heights, MA: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Hudley C, Graham S. An attributional intervention to reduce peer-directed aggression among African American boys. Child Development. 1993;64:124–138. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1993.tb02899.x. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazdin AE. Progression of therapy research and clinical application of treatment require better understanding of the change process. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2001;8(2):143–151. doi: 10.1093/clipsy. 8.2.143. [Google Scholar]

- Kazdin AE. Review of psychotherapy for children and adolescents: Direction for research and practice. Child & Family Behavior Therapy. 2002;24(4):58–64. [Google Scholar]

- Kazdin AE, Kendall PC. Current progress and future plans for developing effective treatments: Comments and perspectives. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1998;27(2):217–226. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp2702_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leff SS, Angelucci J, Goldstein AB, Cardaciotto L, Paskewich B, Grossman M. Using a participatory action research model to create a school-based intervention program for relationally aggressive girls: The Friend to Friend Program. In: Zins MEJ, Maher C, editors. Bullying, victimization, and peer harassment: Handbook of prevention and intervention in peer harassment, victimization, and bullying. Haworth Press; New York, NY: 2007. pp. 199–218. [Google Scholar]

- Leff SS, Costigan TE, Power TJ. Using participatory-action research to develop a playground-based prevention program. Journal of School Psychology. 2004;42:3–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jsp.2003.08.005. [Google Scholar]

- Leff SS, Gullan RL, Paskewich BS, Abdul-Kabir S, Jawad AF, Grossman M, et al. An initial evaluation of a culturally-adapted social problem solving and relational aggression prevention program for urban African American relationally aggressive girls. Journal of Prevention & Intervention in the Community. 2009;37:260–274. doi: 10.1080/10852350903196274. doi: 10.1080/10852350903196274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leff SS, Power TJ, Costigan TE, Manz PH. Assessing the climate of the playground and lunchroom: Implications for bullying prevention programming. School Psychology Review. 2003;32:418–430. [Google Scholar]

- Leff SS, Power TJ, Manz PH, Costigan TE, Nabors LA. School-based aggression prevention programs for young children: Current status and implications for violence prevention. School Psychology Review. 2001;30(3):344–362. [Google Scholar]

- Lochman JE, Boxmeyer C, Powell N, Qu L, Wells K, Windle M. Dissemination of the Coping Power Program: Importance of intensity of counselor training. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2009;77:397–409. doi: 10.1037/a0014514. doi: 10.1037/a0014514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lochman JE, Boxmeyer C, Powell N, Roth DL, Windle M. Masked intervention effects: Analytic methods addressing low dosage of intervention. New Directions for Evaluation. 2006;110:19–32. doi: 10.1002/ev.184. [Google Scholar]

- Lochman JE, FitzGerald DP, Gage SM, Kannaly MK, Whidby JM, Barry TD, et al. Effects of social-cognitive intervention for aggressive deaf children: The Coping Power Program. Journal of the American Deafness and Rehabilitation Association. 2001;35:39–61. [Google Scholar]

- Lochman JE, Fitzgerald D, Whidby J, editors. Anger management with aggressive children. Jason Aronson; Northvale, NJ: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Lochman JE, Nelson WMI, Sims JP. A cognitive behavioral program for use with aggressive children. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1981;10:146–148. doi: 10.1080/15374418109533036. [Google Scholar]

- Lochman JE, Powell N, Boxmeyer C, Qu L, Wells K, Windle M. Implementation of a school-based prevention program: Effects of counselor and school characteristics. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. (in press) doi: 10.1037/a0015013. [Google Scholar]

- Lochman JE, Wells KC. Contextual social-cognitive mediators and child outcome: A test of the theoretical model in the Coping Power program. Development & Psychopathology. 2002a;14(4):945–967. doi: 10.1017/s0954579402004157. doi: 10.1017.S0954579402004157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lochman JE, Wells KC. Contextual social-cognitive mediators and child outcome: A test of the theoretical model in the Coping Power Program. Development and Psychopathology. 2002b;14:971–993. doi: 10.1017/s0954579402004157. doi: 10.1017/S0954579402004157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lochman JE, Wells KC. The Coping Power Program at the middle school transition: Universal and indicated prevention effects. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2002c;16:S40–S54. doi: 10.1037/0893-164x.16.4s.s40. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.16.4S.S40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lochman JE, Wells KC. Effectiveness study of Coping Power and classroom intervention with aggressive children: Outcomes at a one-year follow-up. Behavior Therapy. 2003;34:493–515. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7894(03) 80032-1. [Google Scholar]

- Lochman JE, Wells KC. The Coping Power Program for preadolescent aggressive boys and their parents: Outcome effects at the one-year follow-up. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004;72:571–578. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.4.571. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.4.571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nastasi BK, Varjas K, Schensul SL, Silva KT, Schensul JJ, Ratnayake P. The participatory intervention model: A framework for conceptualizing and promoting intervention acceptability. School Psychology Quarterly. 2000;15:207–232. doi: 10.1037/h0088785. [Google Scholar]

- Nezu AM, Nezu CM. Ensuring treatment integrity. Oxford University Press; New York, NY: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Onken LS, Blaine JD, Battjes RJ. Behavioral therapy research: A conceptualization of a process. American Psychiatric Association; Washington, DC: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Persons JB, Bostrom A, Bertagnolli A. Results of randomized controlled trials of cognitive therapy for depression generalize to private practice. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 1999;23(5):535–548. doi: 10.1023/A:1018724505659. [Google Scholar]

- Rao U, Ryan ND, Birmaher B, Dahl RE, Williamson DE, Kaufman J, et al. Unipolar depression in adolescents: Clinical outcome in adulthood. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1995;34(5):566–578. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199505000-00009. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199505000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rounsaville BJ, Carroll KM, Onken LS. A stage model of behavioral therapies research: Getting started and moving on from stage I. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2001;8(2):133–142. doi: 10.1093/clipsy. 8.2.133. [Google Scholar]

- Seligman ME. The effectiveness of psychotherapy. The Consumer Reports study. American Psychologist. 1995;50(12):965–974. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.50.12.965. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.50.12.965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart DW, Shamdasani PN, Rook DW. Focus groups: Theory and practice. 2nd ed Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Strupp HH, Anderson T. On the limitations of therapy manuals. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 1997;4(1):76–82. doi: 10.111/j.1468-2850.1997.tb00101.x. [Google Scholar]

- Weissman MM, Wolk S, Goldstein RB, Moreau D, Adams P, Greenwald S, et al. Depressed adolescents grown up. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1999;281(18):1707–1713. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.18.1707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van de Wiel NMH, Matthys W, Cohen-Kettenis PT, Maassen GH, Lochman JE, van Engeland H. The effectiveness of an experimental treatment when compared with care as usual depends on the type of care as usual. Behavior Modification. 2007;31:298–312. doi: 10.1177/0145445506292855. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7894(03)80028-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van de Wiel NMH, Matthys W, Cohen-Kettenis P, van Engeland H. Application of the Utrecht Coping Power Program and care as usual to children with disruptive behavior disorders in outpatient clinics: A comparative study of cost and course of treatment. Behavior Therapy. 2003;34:421–436. doi: 10.1177/014544550629855. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson G. Manual-based treatments: The clinical application of research findings. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1996;34(4):295–314. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(95)00084-4. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(95) 00084-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zonnevylle-Bender MJS, Matthys W, van de Wiel NMH, Lochman J. Preventive effects of treatment of DBD in middle childhood on substance use and delinquent behavior. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2007;46:33–39. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000246051.53297.57. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000246051.53297.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]