Abstract

Mental stress—induced myocardial ischemia (MSIMI) has been associated with adverse prognosis in patients with coronary artery disease (CAD), but whether this is a uniform finding across different studies has not been described. We conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies examining the association between MSIMI and adverse outcome events in patients with stable CAD. We searched PubMed, EMBASE, Web of Science, and PsycINFO databases for English language prospective studies of patients with CAD who underwent standardized mental stress testing to determine presence of MSIMI and were followed up for subsequent cardiac events or total mortality. Our outcomes of interest were CAD recurrence, CAD mortality, or total mortality. A summary effect estimate was derived using a fixed-effects meta-analysis model. Only 5 studies, each with a sample size of <200 patients and fewer than 50 outcome events, met the inclusion criteria. The pooled samples comprised 555 patients with CAD (85% male) and 117 events with a range of follow-up from 35 days to 8.8 years. Pooled analysis showed that MSIMI was associated with a twofold increased risk of a combined end point of cardiac events or total mortality (relative risk 2.24, 95% confidence interval 1.59 to 3.15). No heterogeneity was detected among the studies (Q = 0.39, I2 = 0.0%, p = 0.98). In conclusion, although few selected studies have examined the association between MSIMI and adverse events in patients with CAD, all existing investigations point to approximately a doubling of risk. Whether this increased risk is generalizable to the CAD population at large and varies in patient subgroups warrant further investigation.

One-third to 1/2 of patients with coronary artery disease (CAD) develop myocardial ischemia in response to laboratory mental stress.1 Mental stress—induced myocardial ischemia (MSIMI) is a distinct phenomenon from physical (exercise or pharmacologic) stress—induced myocardial ischemia. Unlike physical stress—induced myocardial ischemia, MSIMI is less likely to result in chest pain and electrocardiographic changes, indicators of ischemia,2 and is not related to severity of coronary atherosclerosis.3 Although the exact mechanisms are unknown, MSIMI may in part result from abnormal vasomotion secondary to sympathetic nervous system activation.3 A number of observational studies have reported an association between MSIMI and adverse cardiac events or total mortality. Nonetheless, these studies were small and used a variety of stressor types and diagnostic criteria for MSIMI. Whether these variations affect the prevalence of MSIMI and its relation with adverse outcomes is not known. Clarification of the prognostic importance of MSIMI is fundamental, because, if its role is established, mental stress testing could transition from the research domain to clinical care. This is particularly true given that effective treatment modalities to reduce MSIMI are emerging.4,5 Therefore, we undertook a systematic review and meta-analysis with the primary objective of summarizing the existing evidence of the association between MSIMI and adverse outcomes in patients with CAD.

Methods

We systematically searched PubMed, EMBASE, Web of Science, and PsycINFO to identify prospective studies examining the association between MSIMI and subsequent outcomes in patients with CAD. Search terms, described in detail in the Supplementary Appendix, included “myocardial ischemia,” “ischemic heart disease,” “mental stress,” “psychological stress,” “mental* stress*,” “psychologic* stress*,” and “ischemi*.” The search was limited to studies published in English. To identify potential studies not captured by our database search strategy, we also searched studies listed in the bibliography of relevant publications and reviews.

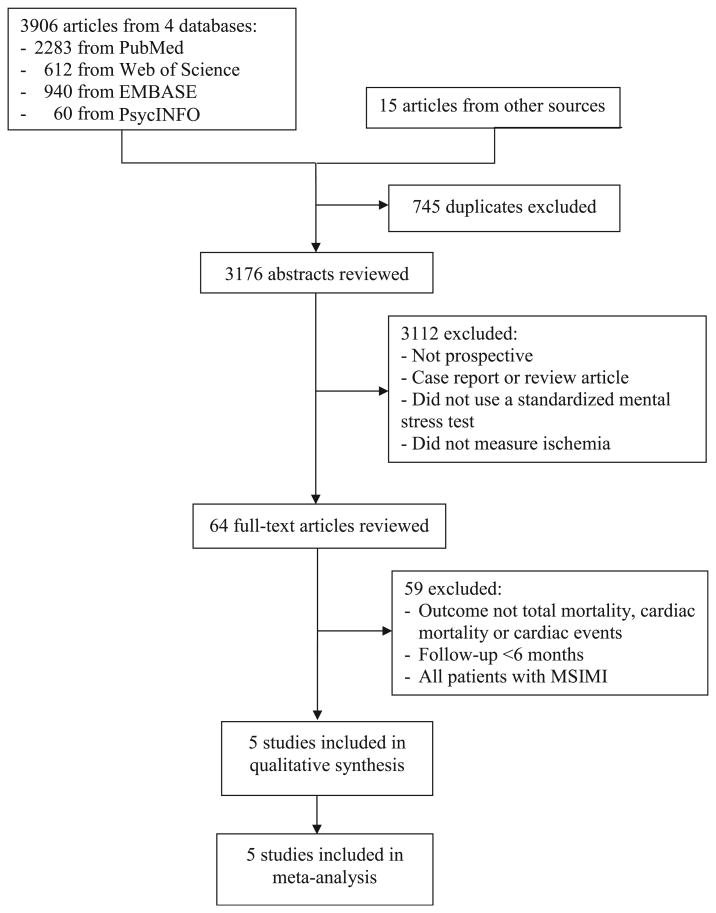

We included studies that (1) were prospective with a follow-up of at least 6 months; (2) were published in English in peer-reviewed journals from 1966 through March 2013; (3) included participants with documented stable CAD; (4) assessed presence of MSIMI using standardized mental stress tests and accepted techniques to assess ischemia; and (5) assessed recurrence of CAD events, cardiac mortality, or total mortality at follow-up. We further excluded studies in which all participants had MSIMI at baseline (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flowchart showing selection of study reports for the meta-analysis.

Study selection was conducted in 2 steps. First, the titles of studies identified in our literature search were independently reviewed by 4 reviewers (JW, RR, CR, and VV). Second, the abstracts of studies that remained after the first-level screening were reviewed by 2 reviewers (RR and CR) and disagreements were reconciled.

Data from studies that met inclusion criteria were independently extracted by 2 reviewers (JW and CR). The data extracted included descriptive information about each study sample size, study design, follow-up length, type of mental stressor, method of assessing myocardial ischemia, and outcome variables. Disagreement was resolved by consensus or, when necessary, adjudicated by a third reviewer (RR). The definition of MSIMI was based on the criteria of each individual study.

Quality assessment was conducted using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale for observational studies,6 which recognizes quality indicators in 3 general domains: selection of exposed and nonexposed cohorts (representativeness of the exposed cohort, selection of the nonexposed cohort, ascertainment of exposure, and demonstration of absence of outcome at the beginning of studies), comparability of exposed and nonexposed cohorts (analysis appropriately adjusted for potential confounding factors, such as medications, history of other chronic diseases, and lifestyle factors), and outcome ascertainment (adequacy of outcome assessment, length of follow-up, and adequacy of follow-up, i.e., losses are not related to either the exposure or the outcome). A study could be awarded a maximum of 1 point for each variable within each assessment domain (selection, comparability, and outcome) for a possible maximum total score of 8. The quality assessment was conducted independently by 3 reviewers (CR, RR, and AJS), and the results were reconciled until a consensus was reached.

Relative risks and 95% confidence intervals were initially calculated from each study. Data were pooled across studies using fixed-effects meta-analysis models and weighted by the inverse of the estimated variance. A forest plot was created to illustrate individual and pooled risk estimates. Heterogeneity among studies was assessed with the I2 statistic.7 A funnel plot was derived to assess publication bias; with this method, lack of bias is assumed if individual-level data are symmetrically distributed around the true mean, whereas publication bias is suggested if the funnel shape is asymmetrical.8 Subgroup analyses according to sample or protocol characteristics, such as patient demographics, type of stressor, method of MSIMI diagnosis, and length of follow-up, were planned but ultimately not carried out because of the limited number of included studies. All analyses were conducted using Review Manager 5.2 (The Cochrane Collaboration, Oxford, United Kingdom).9

Results

The database search yielded a total of 3,906 citations (Figure 1). An additional 15 studies were identified from the bibliography of relevant reports and reviews. After eliminating duplicates, 3,176 remained. Of these, 3,112 studies were not prospective and were therefore excluded. The 64 remaining reports were retrieved in full-text to be examined in more detail. Of these, 59 were ultimately excluded for not meeting other inclusion criteria. Five studies10–14 met the inclusion criteria and were included in the systematic review and meta-analysis.

The 5 cohort studies10–14 were all from the United States, and the pooled sample included 555 participants with 117 outcome events. Table 1 summarizes main study characteristics. The number of participants ranged from 30 in the study by Jain et al10 to 182 in the study by Sheps et al.13 The mean age ranged from 58 to 64 years. The proportion of women was small, and the pooled sample was 85% male. Three of the 5 studies10,12,13 did not provide information on the racial composition of the sample; in the remaining 2 studies11,14 the sample was predominantly white (96% and 77%, respectively). The follow-up period ranged from 35 days to 8.8 years.

Table 1. Characteristics of the 5 cohort studies included in the meta-analysis.

| Study | n | % Women | Mean Age, y |

Mean/Median Follow-Up (Range) |

Stressor/Length | Criteria for MSIMI | Outcome | No. of Events | MSIMI Prevalence |

Lost to Follow-Up |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jain (1995)10 | 30 | 0 | 64.0 | 2 y | Arithmetic/5–6 min | Reduction in LVEF ≥5% for ≥2 min by RNV | Non-fatal MI or unstable angina | 14 | 50% | 0 |

| Jiang (1996)11 | 126 | 11% | 59.0 | 44 m (2–5 y) | Arithmetic/3 min; PS/3 min; MT/3 min SI/20 min |

WMA or reduction in LVEF >5% by RNV | Non-fatal MI, revasc, or cardiac death | 28 | 67% | 7% |

| Krantz (1999)12 | 79 | 4% | 58.0 | 3.5 y (2.7–7.3 y) | PS/5 min; Arithmetic/5 min; |

WMA by echocardiography or RNV | Non-fatal MI, revasc, or cardiac death | 28 | 57% | 18% |

| Sheps (2002)13 | 182 | 14% | 63.0 | 5.2 ± 0.4 y | PS/5 min; ST/5 min | WMA by RNV | All-cause mortality | 15 | 20% | 7% |

| Babyak (2010)14 | 138 | 30% | 62.0 | 5.9 y (35 d–8.8 y) | PS/5 min; MT/5 min | Reduction in LVEF ≥5% by RNV | Non-fatal MI or all-cause mortality | 32 | 19% | 4% |

CAD = coronary artery disease; ECG = electrocardiography; LVEF = left ventricular ejection fraction; MI = myocardial infarction; MSIMI = mental stress–induced myocardial ischemia; MT = mirror tracing; PS = public speaking; Revasc = revascularization procedures; RNV = radionuclide ventriculography; SI = structural interview; ST = stroop test; WMA = wall motion abnormalities.

Except for one,10 all the studies used multiple mental stress tasks in a single session. These included various combinations of mirror tracing, public speaking, cognitive testing, structured interviews, and stroop testing. The length of mental stress testing also varied. Myocardial ischemia was assessed using radionuclide ventriculography in all studies; in one,10 echocardiography was also used. Criteria for MSIMI were not consistent and included the occurrence of wall motion abnormalities during mental stress, a reduction in left ventricular ejection fraction, or both. MSIMI was common in all 5 studies, but, consistent with the different assessment criteria, it varied substantially, from 19% to 67% (Table 1). Clinical outcomes also differed across studies (Table 1) and included all-cause mortality alone or in combination with varying CAD event types, including nonfatal myocardial infarction, cardiac death, revascularization procedures, or unstable angina.

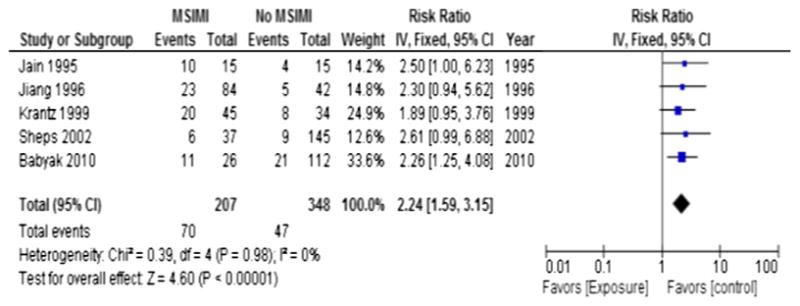

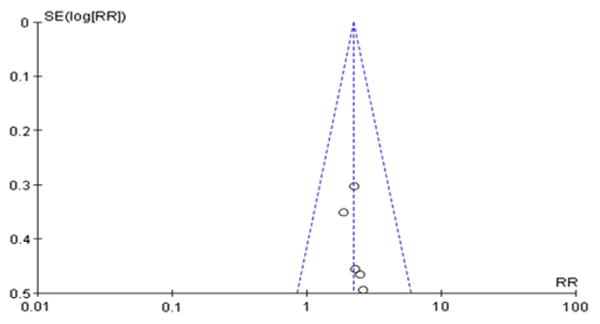

The meta-analysis of the 5 cohort studies indicated that there was a significantly higher risk of cardiac events or total mortality among CAD patients with MSIMI (pooled relative risk 2.24, 95% confidence interval 1.59 to 3.15; Figure 2). No significant heterogeneity of estimates was found among these 5 studies (Q = 0.39, I2 = 0.0%, p = 0.98). The funnel plot (Figure 3) showed good symmetry, which indicates that publication bias is not likely to exist in the analysis.

Figure 2.

Forest plot of the 5 cohort studies included in the meta-analysis. Squares indicate risk ratio estimates for individual studies; square size is proportional to the weight of the corresponding study in the meta-analysis. Horizontal lines represent 95% confidence intervals. The diamond represent the pooled relative risk and 95% confidence interval. IV, Fixed stand for inverse variance method, fixed effects model.

Figure 3.

Funnel plot of the 5 cohort studies included in the meta-analysis. RR = relative risk; SE = standard error.

The methodologic quality of the 5 studies included in the meta-analysis, as scored with the Newcastle-Ottawa scale, is presented in Table 2. The mean total score was 6.5 out of a maximum score of 7 (range 5.5 to 8) indicating that, overall, the methodologic quality was moderately good. The 5 studies generally received acceptable scores for the criteria of selection, comparability, and outcome, except for representativeness of the exposed group.

Table 2. Quality assessment of the 5 studies included in the meta-analysis according to the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale.

| Study | Selection | Comparability | Outcome | Total Score |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

| Exposed Cohort Representative |

Selection of Non-Exposed Cohort |

Ascertainment of Exposure |

Outcome not Present at Baseline |

Analysis Adjusted for Confounding Factors |

Assessment of Outcome |

Length of Follow-up |

Adequacy of Follow-up |

||

| Jain (1995)10 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 5.5 |

| Jiang (1996)11 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 |

| Krantz (1999)12 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6.5 |

| Sheps (2002)13 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6.5 |

| Babyak (2010)14 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 |

| Mean score | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.7 | 1 | 1 | 0.8 | 6.5 |

Discussion

The present systematic review and meta-analysis identified only 5 prospective studies that have investigated MSIMI as a prognostic factor in patients with CAD. All these studies pointed to an association between MSIMI and adverse outcomes. The pooled relative risk was 2.24 (95% confidence interval 1.59 to 3.15), and there was no significant heterogeneity across the studies, despite variations in mental stress protocols, assessment methods, and outcome measures. Our pooled analysis confirms a strong association between MSIMI and adverse outcome events in patients with CAD. However, it also identifies substantial limitations in the current literature. First, only 5 prospective studies have examined the association between MSIMI and subsequent cardiac events or total mortality. Second, these 5 studies were mostly based on small selected samples with few female and minority participants. Third, most studies incompletely adjusted for potential confounding factors such as medication use and history of other chronic diseases. Finally, most studies were based on cohorts enrolled decades ago, and none used myocardial perfusion imaging, which is believed to be more accurate for the detection of MSIMI than methods based on changes in left ventricular function.15 Because mental stress increases peripheral vascular resistance,3,16 changes in left ventricular function may reflect an increase in afterload rather than ischemia.15 Despite these limitations and substantial differences in assessment protocols, it is remarkable that these studies yielded similar results.

A previous meta-analysis by Chida and Steptoe17 reported that greater cardiovascular responses to laboratory mental stress and poor recovery from stress were prospectively associated with broadly defined cardiovascular risk status. This meta-analysis, however, did not examine MSIMI as a predictor of clinical outcomes. In a systematic review, Strike and Steptoe1 provided a comprehensive description of the MSIMI literature; this report, however, did not examine the pooled association between MSIMI and cardiac events or mortality. Therefore, to our knowledge, ours is the first study to summarize existing literature on the prospective association between MSIMI and adverse outcome events in patients with CAD.

The precise mechanisms for the association between MSIMI and adverse outcomes are unclear. One possibility is that mental stress causes both coronary artery vasoconstriction and increased heart rate and/or blood pressure, thereby resulting in myocardial oxygen supply-demand mismatch.15,18 This is supported by evidence linking mental stress to impaired endothelial function,19 exaggerated peripheral microvascular tone,3,16 and vasoconstriction of normal coronary artery segments.20 These vasomotor effects likely occur through the activation of stress-response systems; indeed, plasma catecholamines increase rapidly with mental stress and correlate with hemodynamic changes.21 Mental stress can also induce cardiac electrical instability, as shown by an increase in T-wave alternans and other measures of abnormal cardiac repolarization that are predictors of cardiac arrhythmias and sudden cardiac death.22–24

This meta-analysis is limited by the fact that only 5 studies met our inclusion criteria. This small number underscores the limited literature on this subject, despite the strong associations found by individual investigations. As a result, representativeness of the findings cannot be ensured. Although funnel plot analysis did not suggest publication bias, such analysis may not be informative when the number of studies is small, and thus publication bias cannot be excluded. We also found that women and minority patients were severely underrepresented in these studies. This is important to note because specific demographic segments, for example, women, may be at increased risk for MSIMI.25,26 Finally, our meta-analysis did not assess mechanisms, and because of the small number of investigations, we were not able to explore patient correlates of MSIMI, such as patient demographics, depression or anxiety co-morbidity, lifestyle factors, disease severity, and symptom status. Similarly, the limited number of studies precluded us from performing stratified analysis according to important study characteristics, such as type of mental stress protocol and length of follow-up.

Whether MSIMI testing can be useful clinically for patients' risk stratification and management strategies warrants further investigation. Nonetheless, the consistent association found in this meta-analysis and the promising results of 2 recent trials of MSIMI treatment suggest that this phenomenon may have important implications for patient care and secondary prevention. Jiang et al4 showed that a 6-week treatment with the serotonin reuptake inhibitor escitalopram significantly improved MSIMI occurrence compared with placebo. Blumenthal et al5 reported that a 4-month stress management program in patients with MSIMI reduced clinical CAD events relative to usual care and was associated with lower costs. Thus, although more data are needed, MSIMI recognition and management may provide a novel avenue to improve patient outcomes over and above standard treatments of CAD.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants R01 HL109413, 2R01 HL068630, 2K24HL077506, K24 MH076955, R01 HL088726, P01 HL101398, KL2TR000455, and UL1TR000454 from the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Disclosures: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Supplementary Data: Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.amjcard.2014.04.022.

References

- 1.Strike PC, Steptoe A. Systematic review of mental stress-induced myocardial ischaemia. Eur Heart J. 2003;24:690–703. doi: 10.1016/s0195-668x(02)00615-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jain D. Mental stress, a powerful provocateur of myocardial ischemia: diagnostic, prognostic, and therapeutic implications. J Nucl Cardiol. 2008;15:491–493. doi: 10.1016/j.nuclcard.2008.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ramadan R, Sheps D, Esteves F, Zafari AM, Bremner JD, Vaccarino V, Quyyumi AA. Myocardial ischemia during mental stress: role of coronary artery disease burden and vasomotion. J Am Heart Assoc. 2013;2:e000321. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.113.000321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jiang W, Velazquez EJ, Kuchibhatla M, Samad Z, Boyle SH, Kuhn C, Becker RC, Ortel TL, Williams RB, Rogers JG, O'Connor C. Effect of escitalopram on mental stress-induced myocardial ischemia: results of the REMIT trial. JAMA. 2013;309:2139–2149. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.5566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blumenthal JA, Babyak M, Wei J, O'Connor C, Waugh R, Eisenstein E, Mark D, Sherwood A, Woodley PS, Irwin RJ, Reed G. Usefulness of psychosocial treatment of mental stress-induced myocardial ischemia in men. Am J Cardiol. 2002;89:164–168. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(01)02194-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wells G, Shea B, O'Connell D, Peterson J, Welch V, Losos M, Tugwell P. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. Ottawa Hospital Research Institute. [Accessed on 2012;2]; Available at: http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.htm.

- 7.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327:557–560. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Duval S, Tweedie R. Trim and fill: a simple funnel-plot-based method of testing and adjusting for publication bias in meta-analysis. Biometrics. 2000;56:455–463. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341x.2000.00455.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Review Manager (RevMan) [Computer Program] Version 5.2. The Nordic Cochrane Centre: The Cochrane Collaboration; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jain D, Burg M, Soufer R, Zaret BL. Prognostic implications of mental stress-induced silent left ventricular dysfunction in patients with stable angina pectoris. Am J Cardiol. 1995;76:31–35. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(99)80796-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jiang W, Babyak M, Krantz DS, Waugh RA, Coleman RE, Hanson MM, Frid DJ, McNulty S, Morris JJ, O'Connor CM, Blumenthal JA. Mental stress–induced myocardial ischemia and cardiac events. JAMA. 1996;275:1651–1656. doi: 10.1001/jama.275.21.1651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Krantz DS, Santiago HT, Kop WJ, Bairey Merz CN, Rozanski A, Gottdiener JS. Prognostic value of mental stress testing in coronary artery disease. Am J Cardiol. 1999;84:1292–1297. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(99)00560-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sheps DS, McMahon RP, Becker L, Carney RM, Freedland KE, Cohen JD, Sheffield D, Goldberg AD, Ketterer MW, Pepine CJ, Raczynski JM, Light K, Krantz DS, Stone PH, Knatterud GL, Kaufmann PG. Mental stress-induced ischemia and all-cause mortality in patients with coronary artery disease: results from the Psychophysiological Investigations of Myocardial Ischemia study. Circulation. 2002;105:1780–1784. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000014491.90666.06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Babyak MA, Blumenthal JA, Hinderliter A, Hoffman B, Waugh RA, Coleman RE, Sherwood A. Prognosis after change in left ventricular ejection fraction during mental stress testing in patients with stable coronary artery disease. Am J Cardiol. 2010;105:25–28. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2009.08.647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Krantz DS, Burg MM. Current perspective on mental stress-induced myocardial ischemia. Psychosom Med. 2014;76:168–170. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0000000000000054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hassan M, York KM, Li H, Li Q, Lucey DG, Fillingim RB, Sheps DS. Usefulness of peripheral arterial tonometry in the detection of mental stress-induced myocardial ischemia. Clin Cardiol. 2009;32:E1–E6. doi: 10.1002/clc.20515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chida Y, Steptoe A. Greater cardiovascular responses to laboratory mental stress are associated with poor subsequent cardiovascular risk status: a meta-analysis of prospective evidence. Hypertension. 2010;55:1026–1032. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.146621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dakak N, Quyyumi AA, Eisenhofer G, Goldstein DS, Cannon RO., 3rd Sympathetically mediated effects of mental stress on the cardiac microcirculation of patients with coronary artery disease. Am J Cardiol. 1995;76:125–130. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(99)80043-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sherwood A, Johnson K, Blumenthal JA, Hinderliter AL. Endothelial function and hemodynamic responses during mental stress. Psychosom Med. 1999;61:365–370. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199905000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Arrighi JA, Burg M, Cohen IS, Kao AH, Pfau S, Caulin-Glaser T, Zaret BL, Soufer R. Myocardial blood-flow response during mental stress in patients with coronary artery disease. Lancet. 2000;356:310–311. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02510-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Soufer R, Jain H, Yoon AJ. Heart-brain interactions in mental stress-induced myocardial ischemia. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2009;11:133–140. doi: 10.1007/s11886-009-0020-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kop WJ, Krantz DS, Nearing BD, Gottdiener JS, Quigley JF, O'Callahan M, DelNegro AA, Friehling TD, Karasik P, Suchday S, Levine J, Verrier RL. Effects of acute mental stress and exercise on T-wave alternans in patients with implantable cardioverter defibrillators and controls. Circulation. 2004;109:1864–1869. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000124726.72615.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lampert R, Jain D, Burg MM, Batsford WP, McPherson CA. Destabilizing effects of mental stress on ventricular arrhythmias in patients with implantable cardioverter-defibrillators. Circulation. 2000;101:158–164. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.2.158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lampert R, Shusterman V, Burg M, McPherson C, Batsford W, Goldberg A, Soufer R. Anger-induced T-wave alternans predicts future ventricular arrhythmias in patients with implantable cardioverter-defibrillators. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53:774–778. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.10.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jiang W, Samad Z, Boyle S, Becker RC, Williams R, Kuhn C, Ortel TL, Rogers J, Kuchibhatla M, O'Connor C, Velazquez EJ. Prevalence and clinical characteristics of mental stress-induced myocardial ischemia in patients with coronary heart disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;61:714–722. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.11.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vaccarino V, Shah AJ, Rooks C, Ibeanu I, Nye JA, Pimple P, Salerno A, D'Marco L, Karohl C, Bremner JD, Raggi P. Sex differences in mental stress-induced myocardial ischemia in young survivors of an acute myocardial infarction. Psychosom Med. 2014;76:171–180. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0000000000000045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.