Abstract

The suprachiasmatic nucleus of the hypothalamus (SCN) regulates biological circadian time thereby directly impacting numerous physiological processes. The SCN is composed almost exclusively of GABAergic neurons, many of which synapse with other GABAergic cells in the SCN to exert an inhibitory influence on their post-synaptic targets for most, if not all phases of the circadian cycle. The overwhelmingly GABAergic nature of the SCN, along with its internal connectivity properties, provide a strong model to examine how inhibitory neurotransmission generates output signals. In the present work we show that hyperpolarizations that range from 5 to 1000 milliseconds elicit rebound spikes in 63% of all SCN neurons tested in voltage-clamp in the SCN of adult rats and hamsters. In current-clamp recordings, hyperpolarizations led to rebound spike formation in all cells, however, low amplitude or short duration current injections failed to consistently activate rebound spikes. Increasing the duration of hyperpolarization from 5 ms to 1000 ms is strongly and positively correlated with enhanced spike probability. Additionally, the magnitude of hyperpolarization exerts a strong influence on both the amplitude of the spike, as revealed by voltage-clamp recordings, and the latency to peak current obtained in either voltage- or current-clamp mode. Our results suggest that SCN neurons may use rebound spikes as one means of producing output signals from a largely interconnected network of GABAergic neurons.

Keywords: hyperpolarization, GABA, circadian, anode break, back propagation

Introduction

The suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) of the hypothalamus is the location of the master circadian oscillator of mammals (Moore & Eichler, 1972; Stephan & Zucker, 1972; Inouye & Kawamura, 1979). It coordinates numerous physiological processes such as sleep, temperature regulation and feeding, as well as the internal circulating concentrations of several hormones. Many SCN neurons express a “molecular clock” arising from the interconnected positive and negative gene transcription feedback loops that drive rhythmic patterns of action potential generation (Welsh et al., 1995; Herzog et al., 1998; Kuhlman et al., 2003).

The vast majority of SCN neurons are GABAergic and activation of GABAA receptors phase shifts the circadian clock, synchronizes dorsal and ventral SCN neurons, and modulates the action potential firing of individual SCN neurons (Moore & Speh, 1993; Liu & Reppert, 2000; Jobst et al., 2004; Kononenko & Dudek, 2004; Albus et al., 2005). Anatomical and electrophysiological data indicate that individual SCN neurons receive GABAA receptor-mediated synaptic connections from other SCN neurons (Liou & Albers, 1990; Strecker et al., 1997). GABAergic synaptic transmission in the SCN is regulated, in part, by the circadian clock since the frequency of spontaneous inhibitory postsynaptic currents, the extracellular GABA concentration, and paired-pulse depression at a subset of GABAergic synapses show daily variations (Aguilar-Roblero et al., 1993; Itri & Colwell, 2003; Gompf & Allen, 2004; Itri et al., 2004). The majority of experimental observations support the conclusion that GABA is an inhibitory neurotransmitter in the SCN. However, significant controversy exists as to whether GABA is always inhibitory or may at some times of the day be excitatory. Several research groups have observed only inhibitory GABA effects (Gribkoff et al., 1999; Gribkoff et al., 2003; Aton et al., 2006). However, Wagner et al. reported GABA excited the majority of SCN neurons during the day but inhibited most SCN neurons at night (Wagner et al., 1997; Wagner et al., 2001). In contrast, De Jeu and Pennartz observed GABA inhibitory effects during the day but excitatory effects only in a subset of SCN neurons at night (De Jeu & Pennartz, 2002). While resolution of these day-night differences waits additional experiments, it is clear that GABA acts as an inhibitory neurotransmitter in the SCN. Characterizing GABAA-mediated synaptic transmission in the SCN is important because the functional diversity of GABAergic synapses determine properties of GABA-mediated synaptic and extrasynaptic currents, their effects on the activity of the postsynaptic neuron and the network properties of interconnected neurons (Aradi & Soltesz, 2002; Baker et al., 2002). Further, the network of interconnected SCN neurons is required to stabilize the frequency of individual SCN neuronal oscillators (Liu et al., 2007).

Many neurons display the capacity for rebound spike generation - the appearance of an action potential-like waveforms generated upon release from membrane hyperpolarization (Greene et al., 1986; Akasu et al., 1993; Pennartz et al., 1998). In most preparations, action potentials are regarded as the outcome of a strong depolarizing influence. Rebound spike formation, however, provides an intriguing alternative mechanism by which action potentials could arise from inhibitory synaptic events. Post-hyperpolarization rebound events are important mechanisms influencing rhythmic neuronal activity and patterned motor output in a number of systems, are used in songbird song control nuclei and have been proposed to occur in the ganglion cell layer of retina (Eustache & Gueritaud, 1995; Luo & Perkel, 1999; Mitra & Miller, 2007). It is likely that each circuit operates according to different principles but, nevertheless, these findings reinforce the notion that rebound spiking can play important physiological roles in the temporal organization of signal generation (Bevan et al., 2002; Sohal et al., 2006).

In the present work, we determined the relationship between duration and intensity of hyperpolarization and how such conditions could result in spike formation. Rebound spikes may be used by SCN neurons as a means of intercellular communication or to govern the timing of on-going signaling, for example, as a conversion from regular to irregular firing (Kononenko & Dudek, 2004). Coordinated generation of rebound spiking dispersed through SCN could potentially contribute to resetting the phase of the SCN. Consistent with this idea, increased en masse firing in response to local, short GABA applications has been previously reported (Gribkoff et al., 2003), although the specific importance of membrane hyperpolarization and/or rebound spiking has not yet been explored.

To identify what conditions lead to rebound spike formation in SCN neurons, voltage- and current-clamp recordings were carried out to examine rebound spike generation following membrane hyperpolarizations of various strengths and durations. Given that rebound spike formation was observed following a large range of conditions where the strength and duration were manipulated, we argue for the importance of hyperpolarization in not only organizing but generating SCN signaling. Our findings implicate hyperpolarization-mediated spike formation as one alternative to feed-forward depolarization that appears to be available to SCN neurons as part of the electrophysiological signaling mechanisms of this brain region.

Material and Methods

Animals

Adult male Syrian hamsters (Mesocricetus auratus; Charles River; Wilmington, MA) or young adult male Sprague-Dawley rats (8-17 weeks old; River; Wilmington, MA) were used in the present study. All animals were maintained for at least two weeks on a 14:10 hr (hamsters) or a 12:12 (rats) light/dark cycle. Chamber temperature was set to 19-20°C for hamsters and 20-21°C for rats. Food and water were available ad libitum. All recordings were performed during the animal's subjective day. The Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Oregon Health & Science University approved all experimental procedures involving animals and all efforts were made to minimize pain and the number of animals used.

Slice Preparation

Animals were anesthetized with an overdose of halothane and the dorsal skull was removed. Optic nerves and cranial nerves were carefully sectioned followed by the removal of the brain. A block of tissue containing the hypothalamus was placed into ice cold artificial cerebral spinal fluid (ACSF) saturated with 95% O2 and 5% CO2 at physiological pH. ACSF contained in mM: NaCl 128, KCl 5, NaH2P04 1.2, MgCl2 1, CaCl2 2.5, glucose 9, NaHCO3 20, pH 7.4. Coronal slices (200 - 250 μm thick) were cut with a vibrating blade microtome (Leica VT1000; Nussloch, Germany). Typically two slices could be prepared that contained identifiable SCN. Individual slices were transferred to the recording chamber and visualized with a 40× water immersion objective (Leica, Germany) transmitted to a CCD camera (Sony, Tokyo, Japan) and projected onto a PVM 137 monitor (Sony, Tokyo, Japan). Neurons in ventromedial SCN were localized within the slice using heat-filtered infrared DIC illumination. Visually guided somatic recordings were made from slices constantly perfused with oxygenated ACSF (310 mOsm, 4 ml/min) warmed to 33°C.

Electrophysiological Recordings

Recording pipettes with resistances between 8 and 15 MΩ were pulled from capillary tubes (1B150F-4, WPI, Sarasota, FL) using a vertical microelectrode puller (Narishige PP-83 Tokyo, Japan). The internal recording solution contained (in mM): K-gluconate, 130, NaCl, 1, EGTA, 5, MgCl2, 1, CaCl2, 1, Na2ATP, 2-4, HEPES, 10, and 0.4% Neurobiotin (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA), pH adjusted to 7.3 with KOH and osmolarity set within the range of 275 - 280 mOsm.

Neural activity was amplified using an AxoPatch 1-C (Axon Instruments, Burlingame, CA) patch clamp amplifier, passed through an 80 dB/Decade low-pass Bessel filter (frequency 1.7 – 33.3 kHz), digitized (5 – 100 kHz) and sent to a Power Macintosh computer via an ITC-16 (Instrutech Corp., New York, USA) running Pulse 8.53 (HEKA Electronics, Lambrecht, Germany). All recordings had a series resistance below 25 MΩ. Recordings were performed on neurons meeting the following criteria. For on-cell conditions, offset currents were corrected beside the cell of interest. Recording commenced when a seal resistance above 700 MΩ was achieved and stable baselines were observed for at least 1 minute following attachment. Pipette capacitance was compensated in this on-cell recording mode before any data were collected. On-going activity was sampled in on-cell mode for a minimum of 5 minutes to establish that the cell was active and to determine its baseline frequency and firing pattern as regular or irregular. Liquid junction potential of −11 mV was left uncorrected. Electrophysiological activity was displayed in parallel on a storage oscilloscope (Tektronix, Portland, OR) and within the oscilloscope window from the recording software (HEKA Electronics).

When the input resistance in cell-attached mode was greater than 2 GΩ the cell was used for whole-cell recordings; access to the cell was gained by gentle suction. Whole-cell recordings proceeded when the following criteria were met: uncorrected leak current was less than 40 pA, the cell capacitance waveform during a −10 mV test pulse both conformed to a single-exponential decay and returned to baseline, and the baseline recording state was stable for greater than 2 minutes. Our studies were conducted during the subjective day between ZT2 and ZT9 with an average recording length of 29 minutes and some cells recorded as long as 120 minutes.

Testing Protocols

In order to explore in detail the relationships between the strength of inhibition (as indicated by the degree of hyperpolarization), and the properties of post-hyperpolarization spike generation, we conducted experiments where both the duration and magnitude of the hyperpolarizing step were varied. Experiments were conducted for separate pools of cells in either voltage-clamp or current-clamp mode.

The data collected in voltage-clamp mode was analyzed as a single population. Kolmogorov-Smirnov tests did not yield significance when attempting to separate each of the 200 ms steps in the voltage-clamp from the original test matrix when evaluated for probability. This test, however, detected a significant effect that allowed for the differentiation of similar response profiles for different durations of hyperpolarizing steps (H = 94.821, p<0.0001; Kolmogorov-Smirnov). We applied this finding to our data pool to eliminate two time points (200, 600 and 800 ms) from further analysis due to their statistical similarity to neighboring conditions.

We describe here the average amplitude and latency to peak values for the hyperpolarization-induced rebound current, in response to three representative step durations: 5, 400 and 1000 ms, for short, mid and long latencies, respectively. The return holding potentials of -30 mV and -25 mV versus -55 mV were chosen for more careful consideration because they reflect membrane potentials above, near and below action potential threshold. Based on our findings in voltage-clamp, only the reduced stimulation matrix was used to explore relationships between hyperpolarization magnitude and duration on rebound spike formation in current-clamp mode.

In order to compare the results obtained with current-, and those obtained with voltage-clamp, holding current was used to force the cell membrane to approach -55 mV. In current-clamp mode, the test conditions were limited to 5, 400 and 1000 ms steps at increasingly negative increments of 10 pA from a holding current that set the membrane potential to -55 mV, as indicated above. We found that hyperpolarizing currents of -10 pA would produce voltage shifts that resembled the -5 mV steps used in voltage-clamp. Thus, in both sets of experiments we aimed to test a wide range of hyperpolarizations that could be used to construct a full characterization of conditions that would reliably produce rebound spikes that were consistent in their appearance, as well as spikes generated in connection with changes in membrane voltages that are considered to occur biologically, or are conventionally used, to explore identified SCN currents.

In this work we show the effects of manipulating hyperpolarization for duration and magnitude on generation of rebound spikes in terms of altered amplitude, latency to spike peak and probability of spike generation.

Data and Statistical Analyses

Data from either current-clamp or voltage-clamp modes were analyzed with Excel (Microsoft Corp., Redman,WA), Statview, SAS, (Cary, NC) or IgorPro (Wavemetrics, Lake Oswego, OR). To characterize relationships between the experimental conditions in terms of response amplitude, representative values were averaged (n = 5) for the -90 mV hyperpolarizing step conditions for each of the three return plateau subsets at -55 mV, -30 mV and -25 mV. These values were normalized against the results from the 1000 ms hyperpolarization to -90 mV and the return plateau of -25 mV set as the 100% response value. The corresponding results for amplitude from all manipulations in step duration and plateau return were calculated as a percentage of this value. Amplitude data were evaluated with the non-parametric Kolmogorov-Smirnov test (Statview) and the results used to separate the data into two pools of 5 to 400 ms or > 400 to 1000 ms hyperpolarization. Once data pools were categorized into groups of qualitatively and statistically similar results, additional statistical comparisons were conducted between the two groups (t-tests).

Probability reliability scores from voltage-clamp recordings were used to indicate the relative frequency with which a response was observed followed the application of a particular part of the test matrix. Reliability scores (y-axis) were the number of times a rebound spike was observed divided by the total number of applications of a particular voltage step condition, which describes both a particular strength and duration of hyperpolarization step. If, for example, a hyperpolarization to -70 mV for 400 ms generated any rebound current response above baseline, the observation was marked as 1/the total number of stimulus applications.

Amplitude and latency values of peak rebound voltage response were extracted in IgorPro (n = 5). Values were exported to Excel where t-tests and regression analyses were performed. To generate the probability of observing a rebound spike in a given test category, the numbers of observed events were divided by the numbers of trials. In current-clamp recording conditions each cell was only tested once in each condition in order to avoid bias in the amplitude data that could be caused by rundown. Final figures were assembled in Excel or IgorPro and plates were assembled using Adobe Photoshop software.

Results

Spontaneous Firing and Passive Membrane Properties

Passive membrane properties and biophysical parameters of spontaneously firing SCN neurons were characterized in whole-cell patch clamp recording mode. All SCN neurons were recorded during subjective day and spontaneous firing frequencies in on-cell mode ranged from 0.02 to 10 Hz (n = 10) with an average of 6.3 Hz ± 0.7 (mean ± S.E.M; n = 10). The average membrane resistance was 2.3 ± 0.1 GΩ. Immediately following membrane rupture, cells were voltage-clamped with a hyperpolarizing test pulse of −10 mV for 10 ms in order to measure the decay time constant (tau). The decay time constant had an average tau of 1 ms ± 0.002, a value that is consistent with recordings obtained from other neuronal populations of comparable size (Palmer et al., 2003). In whole-cell mode, cells were held at negative potentials, which resulted in suppression of on-going spike activity.

Evaluation of SCN Neurons Spiking Behavior through Depolarization

In order to determine cell viability and to characterize post-hyperpolarization spike properties, SCN neurons were subjected to multiple ramp protocols with depolarization speeds of 0.02 mV/ms to 2.5 mV/ms. We found that all SCN neurons (n = 65/65) responded with inward currents to depolarization ramps exceeding 0.5 mV/ms, an assay which ensured the cell's viability for subsequent tests for rebound spike generation. Current activation occurring upon ramp depolarization was identified as the first fast rising inward current. This current exhibited average amplitude of -720 ± 30 pA and an average rise time (10 - 90%) of 0.7 ± 0.01 ms these values were consistent with earlier reports of action potential formation in SCN neurons (Pennartz et al., 1998; Cloues & Sather, 2003; Teshima et al., 2003). In addition, we observed that spikes generated during depolarization had an average width, measured at mid-depth from the peak, of 1.5 ± 0.01 ms. Notably, the values for average spike width in voltage-clamp were not significantly different from measurements taken under comparable recording conditions in current-clamp (1.3 ± 0.02 ms, n=5). When spikes appeared upon depolarizing ramps, the mean threshold at which they occurred was -33 ± 2.2 mV (uncorrected for LJP of -11 mV). Finally, application of 50 μM lidocaine in the external bath completely abolished the generation of the inward currents during the depolarization ramps, confirming that these fast rising spikes were mediated by voltage-gated Na+ currents. Thus, upon Na+ current blockade, no other voltage-gated currents (e.g., Ca2+) were activated under our recording conditions.

Hyperpolarization-Induced Rebound Spikes in Voltage- and Current-Clamp

The initial test protocol involved a single voltage step from a holding potential of −55 mV to −90 mV and, after 1 second, a return to -55 mV. Under these conditions, we found that 63% of all cells recorded (n = 41/65) generated a robust post-hyperpolarization rebound spike when released from hyperpolarization (Fig. 1A). In the remaining 37% (n = 24/65) of recorded neurons, no rebound spike was observed following hyperpolarization. We attempted to establish if any biophysical parameters allowed us to classify these neurons as a separate group. However, our analyses did not reveal any indication of a conserved property. Based on these findings, we eliminated neurons that did not exhibit rebound spiking behavior from further analysis in the present study. In addition, there were also no clear electrophysiological predictors for which cells would fire rebound spikes. Importantly, the extent to which on-cell firing properties in SCN slice are reflective of natural neuronal activities in circuit, in vivo, is not well understood. Nevertheless, these findings lend support to our hypothesis that release from sustained inhibition could elicit action potential firing in neurons of the primarily GABAergic SCN.

Figure 1.

Hyperpolarization-induced rebound spikes in SCN neurons. A. Representative neuron exhibiting a rebound spike following application of a 1000 ms hyperpolarization from the -55 mV holding potential to -90 mV and return to −55 mV. B-D. Rebound currents recorded from a single representative neuron demonstrating that the kinetics of rebound currents are impacted by multiple parameters of the hyperpolarization step. At early durations (5 ms) rebound spikes only occur reliably at strong hyperpolarization strengths (A). Hyperpolarizations of increased duration (400 ms; B, and 1000 ms; C. trigger rebound spikes more reliably. In addition, for these longer durations, less intense hyperpolarization strengths are required to generate rebound spikes. Importantly, however, rebound spikes are more time-locked after longer hyperpolarization periods, as compared to shorter hyperpolarizations (C-D). E-G. Current-clamp recordings obtained from a single SCN neuron subjected to multiple injection regimens aimed at simulating the voltage-clamp conditions above. Rebound spikes can be observed following short (5 ms) current injections of -30 pA of hyperpolarizing current (E). Current injections of longer durations significantly increased the reliability of rebound spike appearance. In addition, longer current injections (400 vs. 1000 ms) typically triggered rebound spikes with faster kinetics (F and G, respectively). Arrows indicate the release from hyperpolarization.

Changes in the kinetics of the rebound spike were detectable with hyperpolarization protocols that varied the magnitude and/or the duration of the hyperpolarization step. Figures 1B-D provide representative examples of rebound currents generated for the same cell in response to series of membrane hyperpolarizations ranging from a control depolarization of -40 mV, to a hyperpolarization of -90 mV that varied in duration (5, 400 or 1000 ms) then returned to the holding potential. At short durations, changes of the probability of rebound spike generation were the main differences produced by hyperpolarization magnitude. Figure 1B illustrates that for hyperpolarizations of 5 ms it was necessary to strongly hyperpolarize this neuron to -85 and -90 mV in order to generate a rebound spike. At durations approaching 400 ms, increasing the strength of hyperpolarization could result in rebound spikes for most strengths of the hyperpolarizing step (i.e., < -60mV though -90mV) but spikes tended to occur with delayed latency to peak current amplitude (Fig. 1C). In this example, the separation between the earliest peak and the latest was 7.2 ms, a representative spread in latencies to peak current in the 400ms condition that does not appear with 1000 ms hyperpolarizations (Fig. 1D). Recordings obtained in current-clamp mode revealed a robust presence of rebound spikes in most conditions tested (detailed below), in accordance with our voltage-clamp recordings (Fig. 1E-G). Importantly, very few rebound spikes occurred following 5 ms hyperpolarizations, however, when spikes appeared they had a considerably longer latency to peak than hyperpolarizations for either 400 or 1000 ms (Fig. 1E and F, respectively). In addition, in current-clamp recording mode, spikes observed in the 5 ms condition rarely occurred in connection with the hyperpolarization step complicating our ability to determine a causal relationship between our manipulation and spikes that appeared in this condition. In addition to low probability for occurrence, comparisons between 5 ms conditions in voltage-clamp or current-clamp were further hindered by the presence of oscillations in membrane voltage that are observed for SCN neurons hyperpolarized to -55 mV. Hence, deflections in membrane voltage resulting from 5 ms conditions that did not generate a full rebound spike would not be detectable as their amplitude typically falls within normal variability of Vm held around this potential (detailed below).

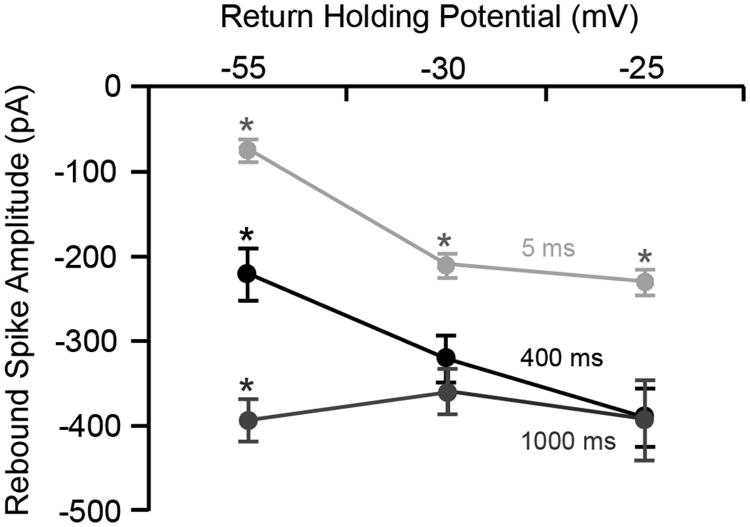

Effects of Hyperpolarization Duration on Rebound Spikes

A 5 ms hyperpolarizing step from -55 mV to -90 mV induced mean rebound currents of -75 ± 11.5 pA, -210 ± 13 pA and -230 ± 15 pA when the return membrane voltages were -55, -30 and -25 mV, respectively. The rebound current at -30 mV and -25 mV were significantly larger than the current recorded at -55 mV (Fig. 2). When the duration of hyperpolarization was increased to 400 ms, mean rebound current amplitude (n = 5) was -220 ± 31 pA, -320 ± 28 pA and -390 ± 35 pA for the same three return potentials mentioned above, respectively. The rebound current at -55 mV was significantly smaller than the currents recorded at -30 mV or -25 mV. Finally, hyperpolarizing the membrane for 1000 ms eliminated the effect of return holding potential on the rebound current amplitude. The mean amplitude for the -55 mV return potential was -470 ± 28.1 pA and not significantly different from the mean amplitudes for the -30 and -25 mV return potentials, which were -430 ± 31 pA and -470 ± 57 pA, respectively (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Rebound spikes are influenced by the post-hyperpolarization return potential. Mean amplitude of rebound spikes plotted as a function of post-hyperpolarization return potential for three representative return plateau conditions (-55, -30 and -25 mV). Short hyperpolarizations (5 ms) are indicated in light grey with hyperpolarizations of 400 and 1000 ms indicated in black and dark grey, respectively. Note that the amplitude of rebound spikes was significantly larger for short duration hyperpolarizations, irrespective of the return holding voltage. This figure also clearly illustrates that, for 400 ms duration hyperpolarizations, the amplitude of the rebound spikes decreases in a quasi-linear fashion, while for long durations (∼1000 ms), rebound spike amplitude was not significantly altered irrespective of the return voltage. Vertical lines for each data point represent standard errors and asterisks indicate statistical significant (p < 0.05).

We next tested if hyperpolarization duration impacted rebound spikes following increases in magnitude of the hyperpolarization. Two conditions of hyperpolarization (-65 mV and -85 mV) and the effects of the three step durations were tested (5, 400 and 1000 ms). We found that hyperpolarization of neurons for different durations did not significantly impact the amplitude of the rebound spikes, for either current injection magnitudes (p = 0.162 and p = 0.092, for -65 and -85 mV, respectively). However, there was a significant effect of hyperpolarization duration on both the latency to spike peak, and the probability of spike occurrence (detailed below).

Effects of Step Duration and Return Voltage on Spike Formation

Comparisons were made between spike amplitudes reached following 5 or 400 ms for each condition of hyperpolarization step magnitude to return plateaus of -55 mv versus -30 or -25 mV (Fig. 2). It was determined that mean spike amplitude for each magnitude of step differed significantly between the 5 and 400 ms conditions using a t-test assuming equal variance (p < 0.0001). Similar statistical comparisons were made for the 400 ms and 1000 ms conditions that also were statistically significant for all magnitudes of step (p < 0.0001). Apparent similarities between the amplitude values for the -30 mV and -20 mV rebound conditions were confirmed as t-test comparisons between these groups failed to achieve statistical significance.

With a return potential of -25 mV (i.e., depolarization-initiated spikes), there were no discernable effects of membrane hyperpolarization on the average amplitude of the rebound spike for the 400 and 1000 ms conditions indicating that these cells were capable of firing action potentials and that changes in the spike formation are not affected by sodium channel inactivation. Relative to the 400 ms and 1000 ms conditions, amplitudes of rebound events were generally lesser for both rebound spikes and depolarization-induced events when that event was preceded by a 5 ms hyperpolarization step.

In current-clamp we explored possible correlations between duration and magnitude of hyperpolarization on spike amplitude. Two conditions of moderate strength current injection (-30 pA and −60 pA) were evaluated across 5, 400 and 1000 ms steps. In current-clamp mode this correlation was not significant (R2 = 0.716, p=0.182 and R2 =0.669, p = 0.214, respectively). However, current injections of -90 pA evaluated across 5, 400 and 1000 ms yielded a robust effect of step duration for the comparison between 400 and 1000 ms (R2 = 0. 967, p = 0.009).

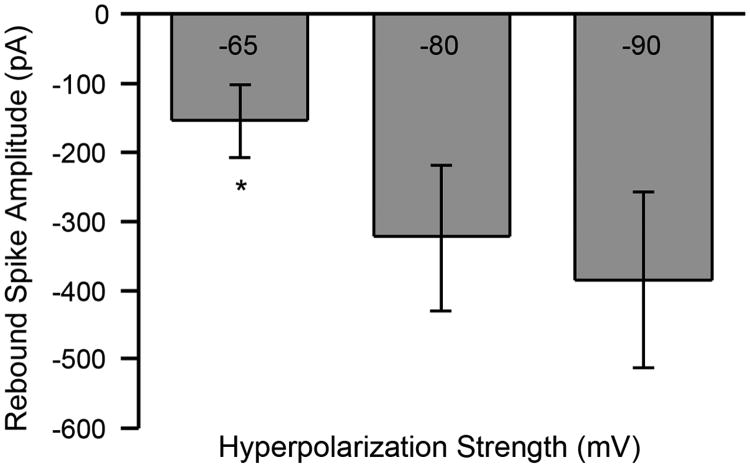

Effects of Strength of Hyperpolarization on Rebound Spike Properties

The effect of the magnitude of membrane hyperpolarization on the rebound current was tested by holding SCN neurons at -55 mV (Vrest) and stepping the membrane voltage in -5 mV increments from -45 mV to -90 mV for multiple durations. For the sake of simplicity, effects of a 400 ms hyperpolarization from a holding voltage of -55 mV to -65, -80 and -90 mV, and a return to -55 mV were reported. The mean rebound spike amplitude (n = 5) was -153 pA ± 51 pA when cells were stepped to -65 mV and returned to Vrest. When SCN neurons were hyperpolarized to -80 mV from Vrest, the average amplitude of the rebound current was -322 pA ± 105 pA. Finally, the strongest hyperpolarization (-90 mV) triggered an average rebound current of -383 pA ± 127 pA. Although the amplitude of the rebound current was not significantly different for hyperpolarizations of -80 and -90 mV, a significant difference was observed when comparing these values to those obtained with a step hyperpolarization to -65 mV from Vrest (Fig. 3). Further analysis tested the strength of the relationship between hyperpolarization magnitude and rebound spike amplitude in current-clamp mode. Our results showed that significant effects could be detected for both the 400 (R2 = 0.795, p < 0.0001) and 1000 ms conditions (R2 = 0.94; p < 0.0001). These findings suggest that the convergence of inhibition from multiple sources and/or the synaptic strength of hyperpolarization may be critical elements stabilizing the output of the SCN neurons.

Figure 3.

Hyperpolarization strength impacts the amplitude of rebound spikes. Mean amplitude (± SE) of rebound spikes for three conditions of hyperpolarizing steps (-65mV to -80 and -90mV). This graph illustrates that increased strengths of hyperpolarization tend to generate more vigorous rebound spikes.

Effects of Hyperpolarization on Latency to Spike Peak

The greatest effects on the latency to post-hyperpolarization spike peak were observed between the 400 ms and 1000 ms step conditions. The variability of the latency to peak was a function of the hyperpolarization step magnitude. For example, the mean latency to peak current (n = 5), following a 400 ms hyperpolarization to -60 mV step was 1.5 ± 0.5 ms. This variability was greatly reduced when the same voltage step was applied for 1000 ms, yielded an average latency of 1.3 ± 1.0 ms. When latency was assessed following large hyperpolarizing steps to -90 mV, the latencies obtained for 400 and 1000 ms step durations were 1.2 ± 0.3 and 1.6 ± 0.3 ms. Thus, the highest variability occurred for voltage steps with intermediate durations (e.g., 400 ms) whereas variability decreased consistently for longer duration hyperpolarizations. Interpretation of the latency data following 5 ms steps must take into consideration the low probability for spike occurrence for short hyperpolarizations (see previous section). Given that increased length of hyperpolarization was associated in our study with decreased variability for latency to peak current, longer hyperpolarizations may be used by the SCN circuitry to stabilize phase relationships between adjacent or interacting cells.

In current-clamp, there were clear effects of hyperpolarization step duration on the mean latency to the rebound spike peak. When short hyperpolarizations of 5ms were followed by a depolarizing spike, the event occurred with a long latency 158 ms ± 7 (mean ± S.E.). Given the low probability of observing a spike event with short hyperpolarizations, any relationship between hyperpolarizations of this length and spike production should be considered tenuous. Injections of hyperpolarizing current lasting 400 or 1000 ms clearly yielded rebound spikes under most circumstances. Mean latency for rebound spike peak for the 400 ms condition averaged over all magnitudes of hyperpolarization was 54 ms ± 13. Steps of 1000ms yielded rebound spikes which, on average, peaked more quickly with a mean value of 31 ms ± 7 (Fig. 4). Although no significant differences between hyperpolarization duration and latency to rebound spike peak were detected between the 400ms and 1000ms conditions, both of these longer durations varied significantly when compared with the 5ms condition (p < 0.05) (Fig. 4).

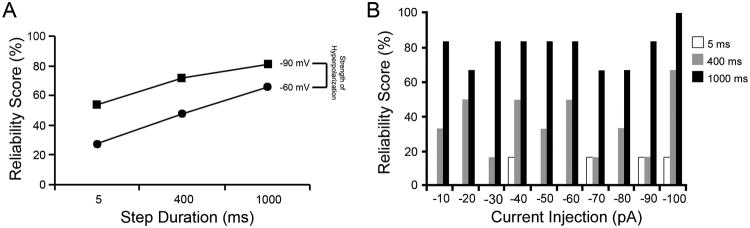

Figure 4.

Hyperpolarization duration positively influences the probability rebound spike occurrence. A. Reliability scores (see methods for details), a measure of the probability of spike occurrence, increases with longer hyperpolarization durations for all the return holding potentials investigated. Illustrated are representative data that were obtained from -60 mV and -90mV holding potentials. Note that spike probability increases linearly as a function of increased hyperpolarization duration (5 ms < 400 ms < 1000 ms). B. Data obtained with current-clamp recordings also demonstrate that longer hyperpolarizations increase the probability of rebound spike occurrence. Note the low probability of observing spikes in connection with hyperpolarizing current injections of 5 ms. This probability significantly increased following longer hyperpolarizations (400 and 1000 ms).

Effects of Hyperpolarization on Spike Probability

The probability of spike occurrence was regulated by an interaction of two parameters: the duration and the magnitude of the hyperpolarizing step, which likely reflected the processes of spatial and temporal summation. A low probability of rebound spike occurrence (n = 5, 27.6%) was observed following a small, short duration hyperpolarization (e.g., -60 mV for 5 ms, Fig. 5A). We also found that increasing the inhibitory step duration had a positive effect on the probability of rebound spike occurrence following a large hyperpolarization. For both 400 ms and 1000 ms hyperpolarizations, the probability of eliciting spikes following small membrane potential steps (e.g., -60 mV) was 48.0 and 66.0%, while an almost linear increase in the probability was observed for larger hyperpolarization steps (72.3 and 81.3% for 400 and 1000 ms, respectively, following a -90 mV step) (Fig. 5A). The interaction between hyperpolarization magnitude and duration in rebound spike generation by SCN neurons likely reflects the spatial or temporal summation of inputs but may also be used to precisely time single neuronal discharges within the network, and therefore may be an important mechanism synchronizing the phase of multiple neurons that are functionally related.

Figure 5.

Latency to peak of rebound spike is dependent on the history of membrane hyperpolarization. Illustrated are latencies averaged across all magnitudes of hyperpolarization, for three representative durations (5, 400 and 1000 ms). Note that shorter hyperpolarizations lead to slower latency to rebound spike peak, whereas longer durations lead to significantly shorter latencies. Hyperpolarizations that exceed 400 ms do not significantly differ from those that approach 1000 ms.

The effects of membrane hyperpolarization on the probability of rebound spike formation recorded in current-clamp yielded results that mirrored the findings obtained with voltage-clamp. The probability of rebound spike occurrence in current-clamp increases as a function of the length of hyperpolarization (Fig. 5B). In addition, although more variable when compared to our voltage-clamp data, higher current injections tended to increase the frequency with which rebound spikes tended to occur in current-clamp mode (Fig. 5B). In general, the greater or longer the hyperpolarization of the cell membrane, the higher the probability of rebound spike formation in either voltage- or current-clamp mode.

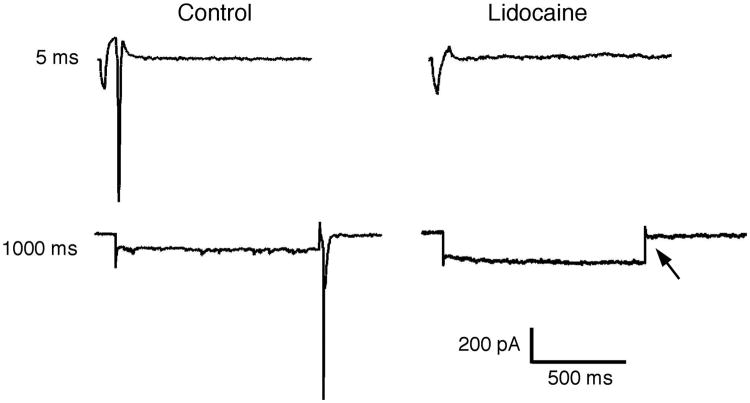

To unequivocally confirm that the rebound current was carried by Na+, we blocked Na+ channels by adding lidocaine (50 μM) to the recording chamber. Lidocaine, an anesthetic agent, was chosen because it blocks both tetrodotoxin (TTX)-sensitive and TTX-resistant Na+ currents. Lidocaine treatment completely blocked hyperpolarization-induced rebound spike behavior, for all durations and magnitudes of the hyperpolarization step (Fig. 6). In the absence of the Na+ component of the rebound spike, no other current responses were detectable at any hyperpolarization durations (5 - 1000 ms).

Figure 6.

Sodium channel antagonist lidocaine completely blocks rebound spike formation. Rebound spikes detected after 5 (top) and 1000 ms (bottom) hyperpolarization, when stepping a representative neuron from -55 to −90 mV, and returning to -55 mV. Rebound spikes are completely in the same neurons following bath application of lidocaine (50 μM). Arrow indicates where the post-hyperpolarization rebound spike should have been generated.

Discussion

Membrane hyperpolarization triggers a rebound spike in the majority of SCN neurons, suggesting that this phenomenon may be a form of neural communication or underlie processing in this hypothalamic nucleus. For cells that were recorded in either voltage-clamp or current-clamp, the probability of spike generation was greatly increased when hyperpolarization dropped below a membrane voltage of -65 mV and lasted for more than 400 ms. While these hyperpolarizations could be achieved by activating a number of ionic conductances, we have shown here that the fast rising component of the response is driven by Na+.

The main finding of the present work was that the duration of the hyperpolarization exerts a major influence on the probability of rebound spike formation. The fact that rebound spikes were observed for a particular neuron below its threshold for action potential generation is a biologically interesting finding that underscores the importance of determining the mechanistic basis of this phenomenon. The magnitude of hyperpolarization apparently plays a secondary, and seemingly independent, role in determining rebound spike behavior, suggesting that these two variables may impact the membrane differently despite the common outcome of spike formation.

Both the probability of detection and the amplitude of hyperpolarization-induced rebound events were low when hyperpolarization periods approached 5 ms. When rebound spikes were observed following a 5 ms hyperpolarization, very few spikes had amplitudes comparable to an action potential yet these spikes were clearly mediated by Na+ and were completely blocked by bath application of lidocaine (Fig. 6). While a biological role for these small depolarizing events activated by short hyperpolarizations is unclear, the generation of partial spikes in voltage clamp conditions provides the opportunity to explore combinations of currents that could impact the set points or thresholds for rebound events. In current-clamp conditions, shorter durations of hyperpolarizations appeared to impact the latency to peak voltage and not amplitude. One interpretation of the combined voltage- and current-clamp findings is that the low amplitude depolarizations observed during voltage-clamp recordings do not manifest when the membrane voltage is not clamped or were not detectable due to membrane oscillations that are normally present in SCN cells held near -60mV.

In voltage-clamp experiments, hyperpolarization that exceeded 400 ms produced the greatest changes in latency to peak current. Variability in both the probability of spike generation and the time to peak current were also strongly reduced as the length of hyperpolarization approached 1 sec. A similar trend was observed in current-clamp experiments whereby increases in hyperpolarization magnitude and duration were both effective in promoting rebound spike formation. By comparing data generated in the 5, 400, and 1000 ms conditions during the current- and voltage-clamp recordings, we surmise that the hyperpolarization duration must approach 400 ms to consistently impact rebound spike formation. The impact of hyperpolarization of very short durations, as would be experienced with a single IPSC, would be strongly determined by the timing of its arrival and would likely only affect the SCN neuron at select points in membrane oscillations, certain conditions of K+ and Ca2+ conductance or in the absence of Ih (see below).

A main finding of this paper was that rebound spikes were primarily mediated by Na+ conductance and that no additional depolarizing waves were observed in the presence of extracellular lidocaine. This observation represents a second important difference in the mechanistic basis of action potential versus rebound spike generation, where certain cells in an oscillating network show a strong calcium component in the early phase of action potential generation. A more striking difference, however, was the appearance of rebound spikes that are generated sub-action potential threshold. Together, these two findings suggest that in the SCN, rebound spikes and action potentials appear similar but may depend upon very different mechanisms in their initiation phases.

Future experiments will be aimed at pharmacologically refining, according to channel subtype, which additional regulators are implicated in rebound spike generation and shape, with anticipated roles for both Ih and IA in regulating this phenomenon. While specific tests for contributions of Ih in rebound spike formation fell beyond the scope of the present work, such experiments are planned for future studies. The known kinetics of this hyperpolarization-induced current suggest that early inward current would counter membrane effects of short hyperpolarizations to oppose the conditions associated with the generation of rebound spikes. The subsequent Ih sag that follows the initial induction is well positioned to interfere with rebound spike formation for periods up to a second, when this current generally deactivates with persistent hyperpolarization. Importantly, although our -90 mV condition does not appear to be applicable with respect to IPSCs mediated by chloride, we detected rebound action potentials also for less negative holding potentials. The consistency with which rebound spikes appear following steps of −90 mV is raises the possibility that Ih and/or IA may further influence aspects of the generation of rebound spikes when mechanisms of membrane hyperpolarization are not mediated by chloride conductance.

Rebound spikes are a type of signaling delay found only in inhibitory networks and may contribute to phase-clustering of neurons in networks of weakly interacting oscillators (Chik & Wang, 2003;Chik et al., 2004). In our slice preparation we noted that rebound spike profile achieved stability in terms of amplitude and time course when the membrane was held at of -90 mV for 1000 ms. The extent to which changes in spike amplitude or delays to peak current provides information to SCN cells is unknown. It is, however, possible that the stabilization of the rebound spike waveform at these conditions may serve as a limit or ceiling mechanism for encoding or indicate that a desired state within the network has been achieved representing some form of asymptote for select SCN networks; the relevance of such a condition remains completely unexplored. Nevertheless, the prevalence of induced rebound spike behavior at SCN neurons suggests that this type of membrane behavior may constitute part of the natural behavior of the system.

In addition to considering the importance of rebound spikes in the forward propagation of signaling in SCN, the biological relevance of back propagation of voltage changes into dendrites should also be considered. Back propagation of spikes has been implicated in mediating synaptic strength, local translation of candidate plasticity genes at the synapse as well as influencing other depolarization-sensitive (biochemically-mediated) mechanisms of plasticity (for reviews see, Bi and Poo, 1998; Braham and Wells, 2007) and therefore may be implicated in on-going or fine-tuning of SCN circuitry.

In our study, the generation of rebound spikes in response to membrane hyperpolarization occurs for conditions where GABA would be inhibitory and would exert a hyperpolarizing influence on SCN cells. There are other possible sources of membrane hyperpolarization that could also be harnessed to generate to the post-inhibition rebound spikes in SCN neurons. In addition to GABA, SCN neurons may be inhibited by the activation of receptors for vasoactive intestinal peptide, GABAB, melatonin, orphanin FQ and serotonin (5‐HT). Each of these compounds activate activates an outward K+ current that hyperpolarizes the membrane potential (Jiang et al., 1995a; Jiang et al., 1995b; Allen et al., 1999; Jiang et al., 2000; Pakhotin et al., 2006). Future studies will be aimed at investigating these possibilities further.

The characterization of inhibition-induced spiking behavior detailed here is expected to improve our understanding of SCN function in at least two ways. First, rebound spike behavior highlights hyperpolarization as a potent mechanism for determining both if and when a spike may occur for a SCN cell. This finding serves as a reminder that inhibitory mechanisms, as well as other means of hyperpolarization, can be used to generate depolarizing spikes with kinetics that strongly resemble action potentials. Moreover, hyperpolarization-induced spikes should, in principle, hold the same possibilities for imparting information as depolarization-initiated spikes. Secondly, rebound spiking behavior has been identified as a characteristic feature of cells that are potentially electrically coupled and that may operate in oscillating circuits (Shinohara et al. 2000; Colwell, 2000; Bevan et al., 2002).

In conclusion, the present work suggests that rebound excitation offers an alternative means of spike generation that is not strictly a consequence of strong depolarizing inputs (i.e., an EPSP dominant environment). In addition, our work highlights the possibility that the recent history of membrane hyperpolarization may influence operations at the network level to define or limit when and where spike activity manifests within the network.

References

- Aguilar-Roblero R, Verduzco-Carbajal L, Rodríguez C, Mendez-Franco J, Morán J, Perez de la Mora M. Circadian rhythmicity in the GABAergic system in the suprachiasmatic nuclei of the rat. Neuroscience letters. 1993;157:199–202. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(93)90736-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akasu T, Shoji S, Hasuo H. Inward rectifier and low-threshold calcium currents contribute to the spontaneous firing mechanism in neurons of the rat suprachiasmatic nucleus. Pflugers Arch. 1993;425:109–116. doi: 10.1007/BF00374510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albus H, Vansteensel MJ, Michel S, Block GD, Meijer JH. A GABAergic mechanism is necessary for coupling dissociable ventral and dorsal regional oscillators within the circadian clock. Curr Biol. 2005;15:886–893. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.03.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen CN, Jiang ZG, Teshima K, Darland T, Ikeda M, Nelson CS, Quigley DI, Yoshioka T, Allen RG, Rea MA, Grandy DA. Orphanin-FQ/nociceptin (OFQ/N) modulates the activity of suprachiasmatic nucleus neurons. Journal of Neuroscience. 1999;19:2152–2160. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-06-02152.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aradi I, Soltesz I. Modulation of network behaviour by changes in variance in interneuronal properties. The Journal of physiology. 2002;538:227–251. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2001.013054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aton SJ, Huettner JE, Straume M, Herzog ED. GABA and Gi/o differentially control circadian rhythms and synchrony in clock neurons. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2006;103:19188–19193. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607466103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker PM, Pennefather PS, Orser BA, Skinner FK. Disruption of coherent oscillations in inhibitory networks with anesthetics: role of GABA(A) receptor desensitization. Journal of neurophysiology. 2002;88:2821–2833. doi: 10.1152/jn.00052.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bevan MD, Magill PJ, Hallworth NE, Bolam JP, Wilson CJ. Regulation of the timing and pattern of action potential generation in rat subthalamic neurons in vitro by GABA-A IPSPs. Journal of neurophysiology. 2002;87:1348–1362. doi: 10.1152/jn.00582.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chik DT, Coombes S, Wang ZD. Clustering through postinhibitory rebound in synaptically coupled neurons. Physical review. 2004;70:011908. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.70.011908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chik DT, Wang ZD. Postinhibitory rebound delay and weak synchronization in Hodgkin-Huxley neuronal networks. Physical review. 2003;68:031907. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.68.031907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cloues RK, Sather WA. Afterhyperpolarization regulates firing rate in neurons of the suprachiasmatic nucleus. J Neurosci. 2003;23:1593–1604. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-05-01593.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Jeu M, Pennartz CMA. Circadian modulation of GABA function in the rat suprachiasmatic nucleus: excitatory effects during the night phase. Journal of neurophysiology. 2002;87:834–844. doi: 10.1152/jn.00241.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eustache I, Gueritaud JP. Electrical properties of embryonic rat brainstem motoneurones in organotypic slice culture. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 1995;86:187–202. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(95)00031-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gompf HS, Allen CN. GABAergic synapses of the suprachiasmatic nucleus exhibit a diurnal rhythm of short-term synaptic plasticity. European Journal of Neuroscience. 2004;19:2791–2798. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2004.03382.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene RW, Haas HL, McCarley RW. A low threshold calcium spike mediates firing pattern alterations in pontine reticular neurons. Science. 1986;234:738–740. doi: 10.1126/science.3775364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gribkoff VK, Pieschl RL, Dudek FE. GABA receptor-mediated inhibition of neuronal activity in rat SCN in vitro: Pharmacology and influence of circadian phase. Journal of neurophysiology. 2003;90:1438–1448. doi: 10.1152/jn.01082.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gribkoff VK, Pieschl RL, Wisialowski TA, Park WK, Strecker GJ, de Jeu MT, Pennartz CMA, Dudek FE. A reexamination of the role of GABA in the mammalian suprachiasmatic nucleus. Journal of biological rhythms. 1999;14:126–130. doi: 10.1177/074873099129000515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herzog ED, Takahashi JS, Block GD. Clock controls circadian period in isolated suprachiasmatic nucleus neurons. Nature neuroscience. 1998;1:708–713. doi: 10.1038/3708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inouye ST, Kawamura H. Persistence of circadian rhythmicity in a mammalian hypothalamic ‘island’ containing the suprachiasmatic nucleus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1979;76:5962–5966. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.11.5962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itri J, Colwell CS. Regulation of Inhibitory Synaptic Transmission by Vasoactive Intestinal Peptide (VIP) in the Mouse Suprachiasmatic Nucleus. Journal of neurophysiology. 2003;90:1589–1597. doi: 10.1152/jn.00332.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itri J, Michel S, Waschek JA, Colwell CS. Circadian rhythm in inhibitory synaptic transmission in the mouse suprachiasmatic nucleus. Journal of neurophysiology. 2004;92:311–319. doi: 10.1152/jn.01078.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson AC, Yao GL, Bean BP. Mechanism of spontaneous firing in dorsomedial suprachiasmatic nucleus neurons. J Neurosci. 2004;24:7985–7998. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2146-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang ZG, Allen CN, North RA. Presynaptic inhibition by baclofen of retinohypothalamic excitatory synaptic transmission in rat suprachiasmatic nucleus. Neuroscience. 1995a;64:813–819. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(94)00429-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang ZG, Nelson CS, Allen CN. Melatonin activates an outward current and inhibits Ih in rat suprachiasmatic nucleus neurons. Brain Res. 1995b;687:125–132. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(95)00478-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang ZG, Teshima K, Yang YQ, Yoshioka T, Allen CN. Pre- and postsynaptic actions of serotonin on rat suprachiasmatic nucleus neurons. Brain research. 2000;866:247–256. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(00)02294-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jobst EE, Robinson DW, Allen CN. Potential pathways for intercellular communication within the calbindin subnucleus of the hamster suprachiasmatic nucleus. Neuroscience. 2004;123:87–99. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2003.08.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kononenko NI, Dudek FE. Mechanism of irregular firing of suprachiasmatic nucleus neurons in rat hypothalamic slices. Journal of neurophysiology. 2004;91:267–273. doi: 10.1152/jn.00314.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhlman SJ, Silver R, Le Sauter J, Bult-Ito A, McMahon DG. Phase resetting light pulses induce Per1 and persistent spike activity in a subpopulation of biological clock neurons. J Neurosci. 2003;23:1441–1450. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-04-01441.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liou SY, Albers HE. Single unit response of neurons within the hamster suprachiasmatic nucleus to GABA and low chloride perfusate during the day and night. Brain research bulletin. 1990;25:93–98. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(90)90257-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu AC, Welsh DK, Ko CH, Tran HG, Zhang EE, Priest AA, Buhr ED, Singer O, Meeker K, Verma IM, Doyle FJ, 3rd, Takahashi JS, Kay SA. Intercellular coupling confers robustness against mutations in the SCN circadian clock network. Cell. 2007;129:605–616. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.02.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu C, Reppert SM. GABA synchronizes clock cells within the suprachiasmatic circadian clock. Neuron. 2000;25:123–128. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80876-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo M, Perkel DJ. A GABAergic, strongly inhibitory projection to a thalamic nucleus in the zebra finch song system. J Neurosci. 1999;19:6700–6711. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-15-06700.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitra P, Miller RF. Mechanisms underlying rebound excitation in retinal ganglion cells. Vis Neurosci. 2007;24:709–731. doi: 10.1017/S0952523807070654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore RY, Eichler VB. Loss of circadian adrenal corticosterone rhythm following suprachiasmatic nucleus lesions in the rat. Brain research. 1972;42:201–206. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(72)90054-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore RY, Speh JC. GABA is the principal neurotransmitter of the circadian system. Neuroscience letters. 1993;150:112–116. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(93)90120-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pakhotin P, Harmar AJ, Verkhratsky A, Piggins H. VIP receptors control excitability of suprachiasmatic nuclei neurones. Pflugers Arch. 2006;452:7–15. doi: 10.1007/s00424-005-0003-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer MJ, Taschenberger H, Hull C, Tremere L, von Gersdorff H. Synaptic activation of presynaptic glutamate transporter currents in nerve terminals. J Neurosci. 2003;23:4831–4841. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-12-04831.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pennartz CMA, de Jeu MT, Bos NP, Schaap J, Geurtsen AM. Diurnal modulation of pacemaker potentials and calcium current in the mammalian circadian clock. Nature. 2002;416:286–290. doi: 10.1038/nature728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pennartz CMA, De Jeu MTG, Geurtsen AMS, Sluiter AA, Hermes MLHJ. Electrophysiological and morphological heterogeneity of neurons in slices of rat suprachiasmatic nucleus. The Journal of physiology (london) 1998;506:775–793. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.775bv.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sohal VS, Pangratz-Fuehrer S, Rudolph U, Huguenard JR. Intrinsic and synaptic dynamics interact to generate emergent patterns of rhythmic bursting in thalamocortical neurons. J Neurosci. 2006;26:4247–4255. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3812-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephan FK, Zucker I. Circadian rhythms in drinking behavior and locomotor activity of rats are eliminated by hypothalamic lesions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1972;69:1583–1586. doi: 10.1073/pnas.69.6.1583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strecker GJ, Wuarin JP, Dudek FE. GABAA-mediated local synaptic pathways connect neurons in the rat suprachiasmatic nucleus. Journal of neurophysiology. 1997;78:2217–2220. doi: 10.1152/jn.1997.78.4.2217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teshima K, Kim SH, Allen CN. Characterization of an apamin-sensitive potassium current in suprachiasmatic nucleus neurons. Neuroscience. 2003;120:65–73. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(03)00270-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomson AM. Slow, regular discharge in suprachiasmatic neurons is calcium dependent, in slices of rat brain. Neuroscience. 1984;13:761–767. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(84)90094-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner S, Castel M, Gainer H, Yarom Y. GABA in the mammalian suprachiasmatic nucleus and its role in diurnal rhythmicity. Nature. 1997;387:598–603. doi: 10.1038/42468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner S, Sagiv N, Yarom Y. GABA-induced current and circadian regulation of chloride in neurones of the rat suprachiasmatic nucleus. The Journal of physiology. 2001;537:853–869. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.00853.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welsh DK, Logothetis DE, Meister M, Reppert SM. Individual neurons dissociated from rat suprachiasmatic nucleus express independently phased circadian firing rhythms. Neuron. 1995;14:697–706. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90214-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]