Abstract

Evidence of social learning, whereby the actions of an animal facilitate the acquisition of new information by another, is taxonomically biased towards mammals, especially primates, and birds. However, social learning need not be limited to group-living animals because species with less interaction can still benefit from learning about potential predators, food sources, rivals and mates. We trained male skinks (Eulamprus quoyii), a mostly solitary lizard from eastern Australia, in a two-step foraging task. Lizards belonging to ‘young’ and ‘old’ age classes were presented with a novel instrumental task (displacing a lid) and an association task (reward under blue lid). We did not find evidence for age-dependent learning of the instrumental task; however, young males in the presence of a demonstrator learnt the association task faster than young males without a demonstrator, whereas old males in both treatments had similar success rates. We present the first evidence of age-dependent social learning in a lizard and suggest that the use of social information for learning may be more widespread than previously believed.

Keywords: cognition, social learning, lizard

1. Introduction

The ability of an organism to learn information about its environment is thought to be adaptive because it pervades so many dimensions of behaviour and ecology [1]. In particular, animals that exploit conspecifics as an information source should be especially advantaged because of their obvious overlap in resource requirements and shared predators. This socially acquired information (social learning) is facilitated through the observation of, or interaction with, another individual [2].

Traditionally, social learning was thought to be the domain of primates and birds [3,4]. More recently, it has been documented for a wider range of organisms including arthropods, turtles, fishes and tadpoles [2]. This is not altogether surprising considering that learning from others is a shortcut to learning the location of a food source or a predator. Therefore, we can predict that social learning need not be restricted to species that exhibit higher frequencies of social interaction. For example, social learning has recently been demonstrated in the red-footed tortoise, a species with relatively low levels of social interaction, and which is able to learn a detour task only in the presence of a demonstrator [5].

The relationship between age and learning ability in animals is poorly understood, although there is some suggestion that younger individuals are more likely to benefit from copying. Examples in support of this idea occur in guppies (age-biased mate choice copying), foraging decisions in nine-spined sticklebacks and foraging innovation in blue tits (juvenile females learn fastest) [2].

Among reptiles, social learning has only been tested in a tortoise (Geochelone carbonaria) [5] and an aquatic turtle (Pseudemys nelsoni) [6]. Lizards are likely to be good candidates for testing social learning because they show behavioural flexibility and rapid learning [7–9]. We tested for age-related social learning in a non-group-living lizard (Eulamprus quoyii) known for relatively rapid spatial learning ability [8,9].

2. Material and methods

We used E. quoyii from our captive colony housed in outdoor enclosures. To remove sex-effects, we used only male lizards for our experiments: n = 18 ‘old’ (approx. 5+ years) and n = 18 ‘young’ lizards (approx. 1.5–2 years; E. quoyii live for up to 8 years). In addition, we used n = 12 old male lizards as ‘demonstrators’ in social demonstration experiments. Cognition trials were conducted in the lizards' home enclosure in the laboratory in opaque tubs (678 (L) × 483 (W) × 418 (H) mm) divided in half with both fixed transparent Perspex and a removable opaque wooden divider.

(a). Social demonstration experiments

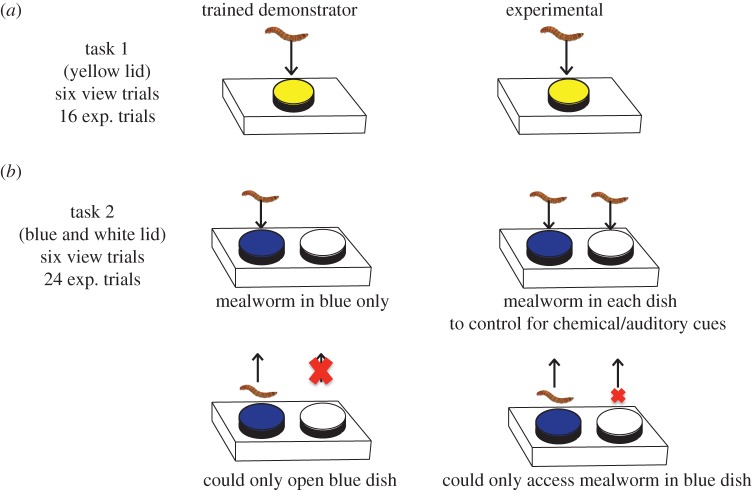

Our social demonstration experiments were modified versions of an instrumental and association-based foraging task previously used with lizards [7,10]. We first accustomed all lizards (n = 48) to eating mealworms (Tenebrio molitor) from an open dish. During the two tasks, the opaque divider and the experimental lizard's refuge and water bowl were removed to provide an unobstructed view of the demonstrating lizard. After 1 h of viewing, the opaque divider was replaced to separate lizards and give the experimental lizard the opportunity to attempt the task. We set up two treatments: (i) social demonstration (hereafter social), where the experimental lizard viewed the demonstrator executing the task, and (ii) social control, where the experimental lizard only viewed the demonstrator (hereafter control). Prior to the experiment, all lizards had a viewing phase in which they viewed the task (social treatment) or just the demonstrator lizard (control) for six trials (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Tasks presented to demonstrators and experimental lizards. (a) Instrumental task and (b) association task. ‘exp.’ = experimental and ‘view trials’ trials: experimental lizard only viewed demonstrator executing task (social demonstration treatment) or a conspecific (control). Large cross: lid could not be opened. Small cross: mealworm not accessible. (Online version in colour. See also online video of lizard attempting task.)

(b). Instrumental task

The first task required experimental lizards (n = 36; 18 social and 18 control) to displace an opaque lid from a food-well by using their snout to lift the lid off the dish (figure 1a). Lizards were given a maximum of 16 trials to complete the task and were considered to have learnt this task when they successfully displaced the lid in 5/6 trials. All lizards that achieved the learning criterion continued to correctly displace the lid on each subsequent trial. Not all lizards learnt and all were trained to remove the lid before commencing the association task (see the electronic supplementary material).

(c). Association task

Two dishes were placed on a wooden block, one with a blue cover (reward) and the other with a white cover (figure 1b). To control for chemical and auditory cues, we placed mealworms in both the white and blue dishes. The food reward in the blue dish was accessible to the lizard, while cardboard blocked access to the mealworm in the white dish (figure 1b). We counter-balanced the location of the blue lid across treatments (right or left side of the approaching lizard); however, the position remained the same across trials. We therefore cannot be certain about the cue (spatial or colour) lizards used (see the electronic supplementary material). In every trial, we scored: (i) latency to choose the blue and white dish and (ii) whether the lizard chose the blue dish or white dish first or only the blue or white. When a lizard displaced the blue lid first, it was scored as a correct choice. Lizards were considered to have learnt the association task when they chose 5/6 trials correctly. We gave lizards a total of 24 trials (12 days) to learn this task. See the electronic supplementary material for more details.

(d). Statistical analysis

We analysed our data using generalized linear models (GLMs) and/or generalized linear mixed models (GLMMs) with the appropriate error distribution for the data. We tested for significant batch, age, treatment and age × treatment effects using likelihood ratio tests. We included individual ID as a random effect in all models. We also included a random slope (trial) in our models; however, this led to poor model convergence. To test the robustness of our results, we re-ran our models using generalized estimating equations and included an AR1 correlation structure. This gave similar results to our GLMMs and thus we present results from our random intercept model. We also tested the robustness of our learning criteria for our association task and found that our criterion of ‘5/6 trials correct’ was sufficient. See the electronic supplementary material for full details on analyses and data availability.

3. Results

(a). Instrumental task

Of 23/36 (64%) lizards that learnt the instrumental task, 11 were old (48%) and 12 young (52%). Seven old lizards and five young lizards that learnt the task were in the social treatment (12/23, 52% total learners). Young lizards in the social treatment had a lower probability of learning (age × treatment interaction: χ2 = 3.97, p = 0.046); however, this effect was marginally significant and became non-significant when accounting for over-dispersion (GLM—quasi-binomial: age × treatment: F = 3.37, p = 0.08). The probability of learning did not depend on treatment (F = 0.12, p = 0.73) or age (F = 0.12, p = 0.73), but was marginally dependent on batch (F = 2.99, p = 0.07).

(b). Association task

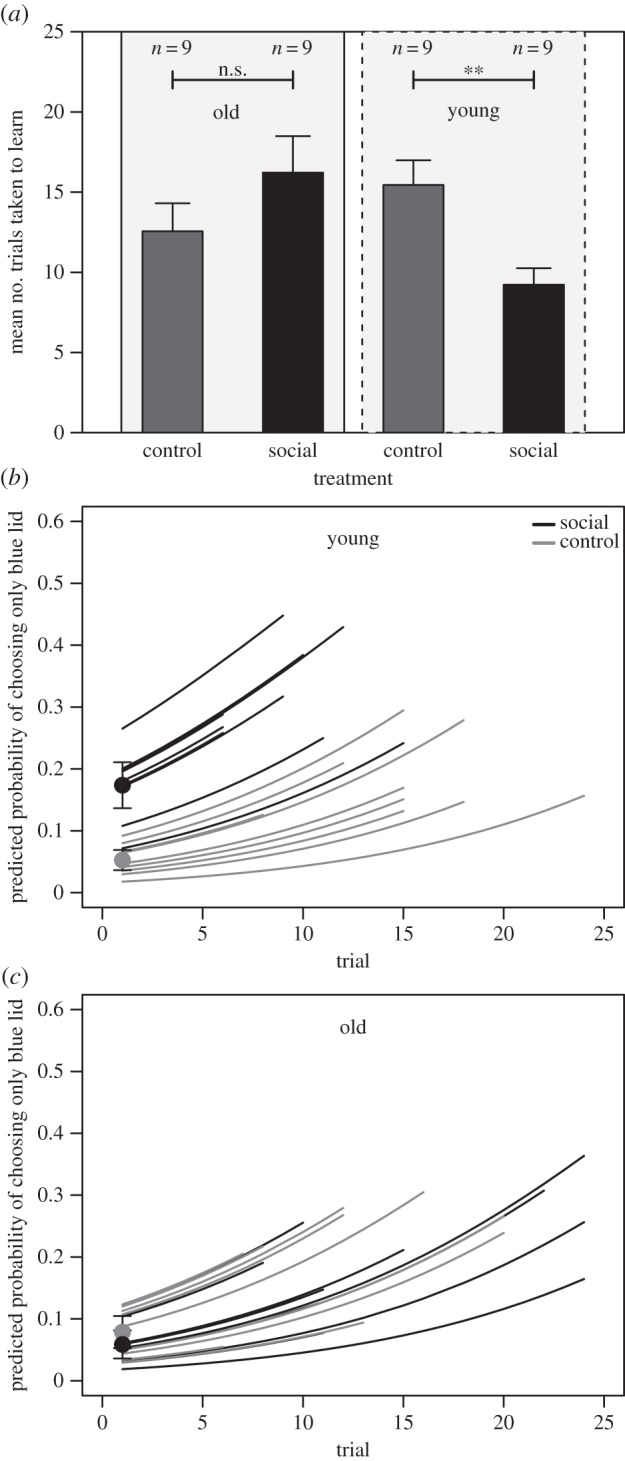

In total, 33/36 (92%) lizards learnt the association task in 24 (or fewer) trials. All young lizards (n = 18) learnt the task, whereas 15 (83%) old lizards (seven social and eight control) learnt. The latency to displace the blue lid did not differ between treatment, age or batch (GLM: age × treatment: F = 2.07, p = 0.16; age: F = 0.06, p = 0.80, treatment: F = 0.12, p = 0.73, batch: F = 0.76, p = 0.48). However, the number of trials it took to learn the association task depended on both age and treatment (GLM: age × treatment: χ2 = 17.40, p < 0.001; batch: χ2 = 7.36, p = 0.03). Young lizards in the social treatment required significantly fewer trials to learn the association task compared with young control lizards (figure 2a; t = −3.35, d.f. = 14, p = 0.005), whereas old lizards in the social and control treatment were not significantly different (figure 2a; t = 1.28, d.f. = 15, p = 0.22). The probability of correctly choosing the blue dish across trials was also dependent on age and treatment (age × treatment: χ2 = 6.1, p = 0.01; batch: χ2 = 4.8, p = 0.09; trial: χ2 = 99.5, p < 0.001). Importantly, the probability of choosing only the blue dish (ignoring the white) across all trials also depended on age and treatment (GLMM: age × treatment: χ2 = 9.2, p < 0.003; batch: χ2 = 8.8, p = 0.01, trial: χ2 = 72.3, p < 0.001). Young lizards in the social treatment had more than twice the probability of choosing only the blue dish and not the white compared with young control lizards (figure 2b). Young social lizards also had a higher probability of choosing only the blue lid on Trial 1 and this probability appeared to increase more steeply with successive trials (figure 2b; electronic supplementary material, S1). By contrast, the probability of choosing only the blue dish did not differ between old lizards in the social and control treatment (figure 2c; electronic supplementary material, S1) and lizards in both treatments had similar predicted probability curves across trials (figure 2c; electronic supplementary material, S1).

Figure 2.

(a) Mean (±s.e.) number of trials to learn association task for ‘old’ and ‘young’ lizards in the social demonstration treatment (social) and control treatment (control). (b,c) Predicted probabilities of choosing only the blue dish within a trial for each lizard in the social demonstration and control treatments: (b) young lizards and (c) old lizards. Each individual's learning trials are plotted up to point of learning; hence, not all individuals are computed for all 24 trials. Black and grey dots are averaged predicted probabilities and 95% prediction interval in Trial 1 averaged across all individuals in social demonstration and control treatments. **Differences significant at α < 0.05.

4. Discussion

Social learning is traditionally considered to be associated with animals exhibiting complex social behaviour [2]. While E. quoyii is not considered a species with social affinity (i.e. group living), individuals are frequently in view of each other in the wild, raising the possibility of social transmission of information. In an instrumental task, we found that lizards in both the social control and social learning treatment learnt to displace the lid from the well containing a food reward but success was unrelated to age or treatment. However, in the association task, only young males used social information to learn which of two differently coloured lids signalled food.

Our current understanding of cognition in lizards is in its infancy [11,12] despite growing appreciation of their cognitive abilities [8–12]. As such, it is currently difficult to make predictions about differences in learning styles and rates between juvenile and adult lizards. Here, younger male lizards used social information to solve an association task, whereas older males did not—perhaps as a result of local enhancement given that we did not observe the same effect in the instrumental task that required lizards to open the food-well. Given that adult males are more likely to exclude male rivals than juveniles from their territories, there may be more opportunity for social learning by juveniles. Furthermore, during this early phase of their life, juvenile lizards may be more likely to benefit from social information through enhanced foraging opportunities and as a result, may be more attentive to the actions of others.

This result is particularly significant given the dearth of studies examining age-dependent effects on social learning. Furthermore, our study is, to the best of our knowledge, the first case of social learning in a lizard and provides compelling evidence that social learning in water skinks is age-dependent.

Research approved by Macquarie University Animal Ethics Committee (ARA 2012/62) and NSW Office of Environment and Heritage (SL100328).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Tim Maher and Shanna Rose for assistance conducting trials.

Data accessibility

Funding statement

We thank the Australian Research Council for funding.

References

- 1.Shettleworth SJ. 2010. Cognition, evolution, and behavior. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hoppitt W, Laland K. 2013. Social learning: an introduction to mechanisms, methods, and models. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reader SM, Laland KN. 2002. Social intelligence, innovation, and enhanced brain size in primates. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 99, 4436–4441. ( 10.1073/pnas.062041299) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lefebvre L. 2010. Taxonomic counts of cognition in the wild. Biol. Lett. 7, 631–633. ( 10.1098/rsbl.2010.0556) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wilkinson A, Kuenstner K, Mueller J, Huber L. 2010. Social learning in a non-social reptile (Geochelone carbonaria). Biol. Lett. 6, 614–616. ( 10.1098/rsbl.2010.0092) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Davis KM, Burghardt GM. 2011. Turtles (Pseudemys nelsoni) learn about visual cues indicating food from experienced turtles. J. Comp. Psychol. 125, 404–410. ( 10.1037/a0024784) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leal M, Powell BJ. 2012. Behavioural flexibility and problem-solving in a tropical lizard. Biol. Lett. 8, 28–30. ( 10.1098/rsbl.2011.0480) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carazo P, Noble DWA, Chandrasoma D, Whiting MJ. 2014. Sex and boldness explain individual differences in spatial learning in a lizard. Proc. R. Soc. B 281, 20133275 ( 10.1098/rspb.2013.3275) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Noble DWA, Carazo P, Whiting MJ. 2012. Learning outdoors: male lizards show flexible spatial learning under semi-natural conditions. Biol. Lett. 8, 946–948. ( 10.1098/rsbl.2012.0813) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clark BF, Amiel JJ, Shine R, Noble DWA, Whiting MJ. 2013. Colour discrimination and associative learning in hatchling lizards incubated at ‘hot’ and ‘cold’ temperatures. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 68, 239–247. ( 10.1007/s00265-013-1639-x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wilkinson A, Huber L. 2012. Cold-blooded cognition: reptilian cognitive abilities. In The Oxford handbook of comparative evolutionary psychology (eds Vonk J, Shackelford TK.), pp. 129–143. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Burghardt GM. 2013. Environmental enrichment and cognitive complexity in reptiles and amphibians: concepts, review, and implications for captive populations. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 147, 286–298. ( 10.1016/j.applanim.2013.04.013) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.