Abstract

BACKGROUND

In critically ill patients, induction with etomidate is hypothesized to be associated with an increased risk of mortality. Previous randomized studies suggest a modest trend toward an increased risk of death among etomidate recipients; however, this relationship has not been measured with great statistical precision. We aimed to test whether etomidate is associated with risk of hospital mortality and other clinical outcomes in critically ill patients.

METHODS

We conducted a retrospective cohort study from January 1, 2001, to December 31, 2005, of 824 subjects requiring mechanical ventilation, who underwent adrenal function testing in the ICUs of 2 academic medical centers. The primary outcome was in-hospital mortality, comparing subjects given etomidate (n = 452) to those given an alternative induction agent (n = 372). The secondary outcome was diagnosis of critical illness-related corticosteroid insufficiency following etomidate exposure.

RESULTS

Overall mortality was 34.3%. After adjustment for age, sex, and baseline illness severity, the relative risk of death among the etomidate recipients was higher than that of subjects given an alternative agent (relative risk 1.20, 95% CI 0.99–1.45). Among subjects whose adrenal function was assessed within the 48 hours following intubation, the adjusted risk of meeting the criteria for critical illness-related corticosteroid insufficiency was 1.37 (95% CI 1.12–1.66), comparing etomidate recipients to subjects given another induction agent.

CONCLUSIONS

In this study of critically ill patients requiring endotracheal intubation, etomidate administration was associated with a trend toward a relative increase in mortality, similar to the collective results of smaller randomized trials conducted to date. If a small relative increased risk is truly present, though previous trials have been underpowered to detect it, in absolute terms the number of deaths associated with etomidate in this high-risk population would be considerable. Large, prospective controlled trials are needed to finalize the role of etomidate in critically ill patients.

Keywords: sepsis, ICU, mortality, etomidate, adrenal function, rapid sequence induction

Introduction

Etomidate, an imidazole derivative, is a commonly used induction agent for emergency tracheal intubation, due to its favorable hemodynamic profile and the conditions it produces to facilitate intubation.1–5 Despite these advantageous features, even a single dose of etomidate induces adrenal suppression.6–10 It does this by interfering with the steroidogenic enzymes 11-β hydroxylase and the cholesterol (p450) side-chain cleavage enzyme, which in turn inhibits cortisol synthesis.11,12 Based on the observed association between adrenal dysfunction and mortality in critically ill patients,13–18 randomized studies (ranging in size from 18 patients to 469) have attempted to address the question of the safety of etomidate for tracheal intubation in this population. A meta-analysis of their results suggests a small trend toward an increased risk of death among etomidate recipients, compared to non-recipients (OR 1.14, 95% CI 0.81–1.60).18 Some observational studies with similar sample sizes have also reported a trend of increased risk of mortality associated with etomidate administration.16,19,20

While the results from previous randomized studies suggest a potentially modest relative increased risk of death associated with receipt of etomidate, it is important to note that these observations were inconclusive due to considerable statistical imprecision (based on sample size) and were compatible with potentially no true relationship existing. Consequently, the results from randomized trial and observational data addressing this question have engendered a robust controversy surrounding the safety of this drug in the critically ill population, particularly those with sepsis.8,21,22 We have attempted to contribute to this debate by offering more precision than previous reports; to date, this is the largest single institution study with complete illness severity data evaluating the association between etomidate exposure and mortality. Therefore the primary aim of this study was to quantify with more precision the potential association between etomidate administration and in-hospital mortality, with a focus on patients with a diagnosis compatible with sepsis and septic shock. The secondary objective was to estimate the association between receipt of etomidate and development of adrenal dysfunction.

Methods

Study Design

We conducted a retrospective cohort study utilizing hospital data from the 5-year admission period January 1, 2001, to December 31, 2005, from critically ill patients at 2 large academic medical centers in Seattle, Washington. The patient population was drawn from the medical and surgical ICUs.

Subjects

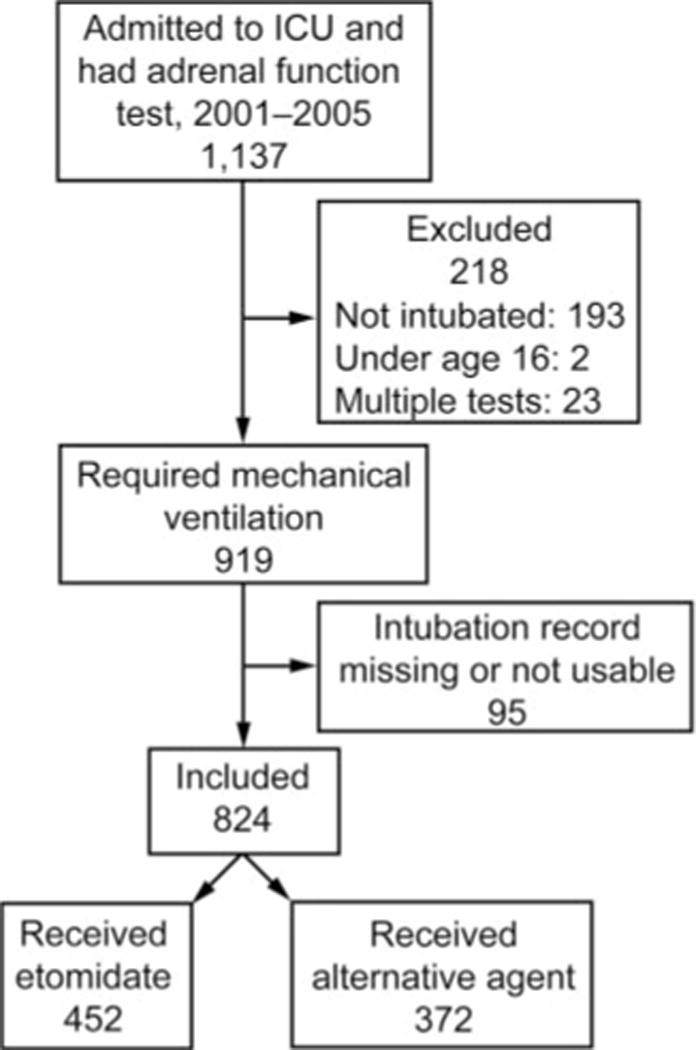

The study population consisted of all ICU patients admitted during the study period and who underwent adrenal function testing at the discretion of their treating physicians. All patients were considered to be critically ill with diagnoses compatible with presumed septic shock. This designation was based on the fact that during the study period (prior to publication of the Corticosteroid Therapy of Septic Shock [CORTICUS]) trial19) it was common practice at this institution to test for adrenal insufficiency in patients with presumed septic shock, and to treat with steroids as indicated.23,24 We restricted our study sample25,26 to patients who were intubated during their hospitalization, had complete intubation records, were older than 16 years of age, and who did not have separate hospitalizations in which their adrenal function was tested while in the ICU (Fig. 1). The University of Washington institutional review board approved this study (University of Washington Human Subjects Review 33671).

Fig. 1.

Study cohort flow chart.

Data Source

All covariate and outcome information was abstracted from the electronic medical record (ORCA Powerchart, Cerner, Kansas City, Missouri). Abstracted data included International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision (ICD-9) codes to identify site of infection.

Outcome Definitions

The primary outcome was all cause mortality during hospitalization. The secondary outcome was development of critical illness-related corticosteroid insufficiency (CIRCI).

The assessment of CIRCI entailed a random total cortisol measurement and the results of a cosyntropin stimulation test. The test involved the measurement of total serum cortisol concentration at baseline, then at 30 and 60 min following administration of 250 μg of cosyntropin. The CIRCI diagnosis was based on the latest consensus statement by the American College of Critical Care Medicine.27 According to the statement, CIRCI can be biochemically defined as either a random total cortisol < 10 μg/dL or an increase in serum cortisol following cosyntropin administration of < 9 μg/dL. We also evaluated adrenal responsiveness alone. Non-responsiveness was defined as a maximum change (Δ max) of 9 μg/dL or less following cosyntropin administration.15,23

Exposure Definitions

The type of anesthetic used during intubation was ascertained by manual chart review. Each subject who underwent adrenal function testing in the ICU during the admission period 2001 through 2005 had his or her chart reviewed for the hospitalization in which the test occurred. Anesthesia, emergency department, and emergency medical services records were queried for information regarding anesthetic type and the date of intubation. If a subject had multiple intubations or multiple surgeries during a hospitalization, each anesthesia record for the hospitalization was queried to assure that an exposure to etomidate was not misclassified.

Statistical Analyses

For etomidate-exposed and unexposed subjects, we performed univariate comparisons of demographic variables and admission disease severity measures using a chi-square test for categorical variables and a 2-sample Student t test for continuous variables, with assumption of unequal variance (Satterthwaite method). We evaluated for confounding based on whether a covariate was associated with etomidate exposure and hospital mortality. Variables were adjusted for if they met these criteria and were not in the causal pathway and not collinear with the a priori defined potential confounders.

Primary Analysis: Multivariate Relative Risk Regression Modeling

Because mortality is a common outcome in this population, estimates are expressed as relative risk.28 For the primary analysis we fitted an unadjusted relative risk regression model with etomidate exposure at any time as the primary independent variable, and hospital mortality as the dependent variable. We used robust (sandwich) variance estimates so that our inference would be valid for possible variance misspecification.29 The plan for building the adjusted model for the primary analysis was specified a priori. To the unadjusted model we added the following a priori defined potential confounders: sex, age and Simplified Acute Physiology Score (SAPS II). (Of note, SAPS II is a validated illness severity measure calculated from physiologic and laboratory parameters obtained during the first 24 h of admission in the ICU; it predicts a probability of hospital mortality for an average patient of a given severity score.30) This model was our adjusted baseline model. As appropriate, we included additional covariates that were found to be confounders in the data set. For the secondary analysis, with CIRCI as the dependent variable, we restricted it to subjects whose adrenal function was tested within the 48 hours following intubation. This interval was chosen as a reasonable time period during which etomidate could exert its effect on the adrenal gland. In addition, because protein levels can affect total serum cortisol levels,31–38 in exploratory analyses we controlled for hypoproteinemia (defined as an albumin < 2.5 g/dL)31 at the time of adrenal function testing, to see if doing so altered the results.

Sensitivity Analyses

We planned a number of a priori sensitivity analyses. First, we tested whether use of a propensity score to control for confounding produced different results from those obtained from the primary adjusted model. A propensity score is an estimate of the probability of being exposed (in this circumstance, to etomidate), based on measured covariates collected at baseline. In accordance with the recommendations of Brookhart et al, we developed the propensity score based on a covariate’s relationship with the outcome, irrespective of its relationship to exposure.39 (The variables used for calculation of the propensity score were age, sex, weight, hospital, illness severity score, albumin level, hypotension on admission, vasopressor requirement on admission, time between admission and intubation, and time from hospital admission to ICU admission.) Additionally, we tested whether the risk of developing CIRCI following etomidate exposure was altered by expanding the time from etomidate administration from 48 to 72 hours prior to adrenal function testing. All hypothesis tests were 2-sided. Analyses were performed using statistical software (Stata 2009, StataCorp, College Station, Texas).

Results

Subject Characteristics

There were 1,167 patients whose adrenal function was tested in the ICU during the study period. After omitting patients younger than 16 (n = 2) and those with multiple admissions (n = 28), there were 1,137 patients, of whom 919 required mechanical ventilation during their hospitalization. Of those 919 patients, 824 had records that indicated the induction agent given at the time of intubation. Characteristics of these 824 subjects are shown in Table 1. Four hundred fifty-two subjects received etomidate, and 372 received another induction agent. Based on a random sub-sample of non-etomidate subjects, the distribution of other induction agents was propofol (59%), midazolam or another benzodiazepine (19%), sodium thiopental (6%), and other (16%). Subjects who received etomidate differed from subjects receiving another induction agent in their age, ICU admission SAPS II and Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) scores,40 proportion with a medical admission, proportion meeting systemic inflammatory response syndrome criteria and requiring a vasopressor within a 24 hour period, site of infection, and the time from hospital admission to intubation (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic, Admission, and Hospitalization Characteristics by Type of Induction Agent

| Etomidate (n = 452) |

Other Agent (n = 372) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Age, mean ± SD y | 59.2 ± 15.7 | 53.4 ± 16.1 |

| Male, no. (%) | 272 (60.1) | 209 (56.1) |

| Weight, mean ± SD kg | 83.1 ± 25.0 | 86.0 ± 32.8 |

| Medical (vs surgical), no. (%) | 224 (49.6) | 215 (57.8) |

| SAPS II, mean ± SD* | 55.8 ± 22.8 | 52.1 ± 21.5 |

| SOFA score, mean ± SD* | 5.0 ± 3.5 | 4.2 ± 3.3 |

| SIRS criteria, no. (%)*† | 306 (45.4) | 367 (54.5) |

| Vasopressor agents at admission, no. (%)* | 282 (62.4) | 214 (57.5) |

| Vasopressor agents + SIRS at any time during ICU stay, no. (%)‡ | 372 (82.3) | 256 (68.8) |

| Site of Infection, no. (%)§ | ||

| Respiratory | 168 (37.2) | 111 (29.8) |

| Primary bacteremia | 88 (19.4) | 72 (19.4) |

| Abdominal | 62 (13.7) | 38 (10.2) |

| Genitourinary | 22 (4.9) | 24 (6.5) |

| Wound/soft tissue | 32 (7.1) | 32 (8.6) |

| Central nervous system | 6 (1.3) | 5 (1.3) |

| Endocarditis | 9 (2.0) | 4 (1.1) |

| Other/undetermined | 65 (14.4) | 86 (23.1) |

| Time between admit and intubation, median (IQR) d | 2 (0–8) | 0 (0–3) |

| Time hospitalized before cortisol test, median (IQR) d | 4 (1–12) | 3 (1–9.5) |

| Albumin, mean ± SD g/dL | 1.9 ± 0.69 | 1.9 ± 0.79 |

| Random total cortisol, median (IQR) μg/dL | 20.8 (14.6–30.0) | 20.4 (14.0–30.0) |

Measured on first day of ICU admission.

In a 24 hour period, 2 or more of the following: heart rate > 90 beats/min, breathing frequency > 20 breaths/min, PaCO2 < 32 mm Hg, white blood cell count < 4,000 cells/mL or > 12,000 cells/mL, temperature < 36°C or > 38°C.

During the same 24 hour period while admitted to the ICU.

Determined using International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision (ICD-9) codes.

SAPS = Simplified Acute Physiology Score

SOFA = sequential organ failure assessment

SIRS = systemic inflammatory response syndrome

The following covariates were associated with etomidate exposure and hospital mortality: age, SAPS II, non-responsiveness to cosyntropin, and SOFA score. Adrenal gland non-responsiveness was presumed to be in the causal pathway following etomidate exposure, and SOFA score was highly collinear with the SAPS II. Neither was used for adjustment in the primary or secondary analyses.

Outcome Measures

The overall cumulative mortality was 34.3% (283 deaths/824 hospitalizations). Approximately 39% of subjects who received etomidate died, compared to 29% of subjects given a different induction agent (Table 2). After adjusting for age, sex, and SAPS II, the relative risk of dying was 1.20 (95% CI 0.99–1.45), comparing subjects who received etomidate to subjects receiving a different agent (see Table 2). Among subjects whose adrenal function was evaluated within 48 hours following intubation, after adjustment, the risk of meeting criteria for CIRCI was 37% higher (relative risk 1.37, 95% CI 1.12–1.66) in subjects receiving etomidate, compared to those receiving a different induction agent (see Table 2). The relative risk for non-responsiveness to cosyntropin was also higher in etomidate recipients (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Hospital Mortality and Diagnosis of CIRCI, by Type of Induction Agent

| Etomidate | Other Agent | Crude Relative Risk (95% CI) |

Adjusted Relative Risk (95% CI)* |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hospital mortality, no. (%) | 175 (38.7) | 108 (29.0) | 1.33 (1.09–1.62) | 1.20 (0.99–1.45) |

| Diagnosis of CIRCI following intubation, no. (%)† | 140 (62.5) | 74 (47.1) | 1.33 (1.09–1.61) | 1.37 (1.12–1.66) |

| Non-responsiveness‡ to cosyntropin following intubation, no. (%)§ | 127 (56.4) | 57 (36.0) | 1.59 (1.25–2.01) | 1.59 (1.26–2.00) |

Adjusted for age, sex, and Simplified Acute Physiology Score (SAPS II).

Restricted to the 412 subjects whose adrenal function was tested within the 48 hours following intubation, of whom 31 had baseline cortisol ≥ 10 μg/dL and Δ max of ≤ 9 μg/dL but were missing data for their 60-min post-stimulation reading, precluding definitive diagnosis of CIRCI. We omitted those subjects. Including them by using their 30-min result provided an adjusted relative risk of 1.37 (95% CI 1.12–1.68).

Non-responsiveness was defined as a Δ max of ≤ 9 μg/dL following administration of cosyntropin.

Restricted to the 412 subjects whose adrenal function was tested within the 48 hours following intubation, of whom 29 subjects had 30-min results of ≤ 9 μg/dL but were missing data for their 60-min post-stimulation reading, precluding definitive diagnosis of non-responsiveness. We omitted those subjects. Including them by using their 30-min result provided an adjusted relative risk of 1.46 (95% CI 1.19–1.78).

CIRCI = critical illness-related corticosteroid insufficiency, defined as a random total cortisol < 10 μg/dL and/or a Δ max cortisol following cosyntropin administration of < 9 μg/dL

Among all subjects, after adjustment, the risk of mortality was significantly higher in those meeting the criteria for CIRCI, compared to those not meeting the criteria for CIRCI (Table 3). The adjusted risk of mortality in subjects with non-responsiveness to cosyntropin, compared to responders, was 1.57 (95% CI 1.29–1.92) (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Risk of Hospital Mortality in Subjects With CIRCI, Non-Responsiveness to Cosyntropin

| Crude Relative Risk (95% CI) for Hospital Mortality | Adjusted Relative Risk (95% CI) for Hospital Mortality* | |

|---|---|---|

| CIRCI vs no CIRCI (reference group)† | 1.32 (1.08–1.61) | 1.31 (1.07–1.59) |

| Non-responders‡ vs responders (reference group)§ | 1.68 (1.38–2.05) | 1.57 (1.29–1.92) |

| Adjusted for hypoproteinemia (albumin ≤ 2.5 g/dL) | ||

| CIRCI vs no CIRCI (reference group) | 1.44 (1.18–1.77) | |

| Non-responders vs responders (reference group) | 1.64 (1.34–2.00) |

All analyses adjusted for age, sex, and Simplified Acute Physiology Score (SAPS II).

In this comparison, 52 subjects had baseline cortisol of ≥ 10 μg/dL and Δ max of ≤ 9 μg/dL but were missing their 60-min post-stimulation results, precluding definitive diagnosis of CIRCI. We omitted those subjects. Including them by using their 30-min result provided an adjusted relative risk of 1.23 (95% CI 1.02–1.48).

Non-responsiveness was defined as a Δ max of ≤ 9 μg/dL following administration of cosyntropin.

In this comparison, 57 subjects had 30-min results ≤ 9 μg/dL but were missing data for their 60-min post-stimulation reading, precluding definitive diagnosis of non-responsiveness. We omitted those subjects. Including them by using their 30-min result provided an adjusted relative risk of 1.56 (95% CI 1.29–1.89)

CIRCI = critical illness-related corticosteroid insufficiency, defined as a random total cortisol < 10 μg/dL and/or a Δ max cortisol following cosyntropin administration of < 9 μg/dL

Sensitivity Analyses

In addition to the SAPS II, the admission SOFA score also met the criteria for confounding. In the model adjusting for SOFA score (in addition to age and sex), the risk of death in those given etomidate relative to those given a different agent was 1.17 (95% CI 0.96–1.42). When the model was adjusted for propensity score only, the risk of mortality was not appreciably different (relative risk 1.18, 95% CI 0.97–1.44). There was no change from the primary findings when the time between intubation and adrenal function testing was extended to 72 hours; subjects given etomidate were more likely to meet the criteria for CIRCI than subjects given a different induction agent (relative risk 1.31, 95% CI 1.10–1.58). Among all subjects, after controlling for hypoproteinemia, age, sex, and SAPS II, the relationship between CIRCI and mortality was not meaningfully different from the original findings; similarly, the association between non-responsiveness and mortality was not meaningfully affected by controlling for hypoproteinemia (see Table 3).

Discussion

In this study we observed a trend toward somewhat higher in-hospital mortality in intubated subjects with suspected septic shock who had received etomidate, compared to similar subjects who received a different induction agent. The subjects who were given etomidate had a 37% increased risk of meeting the criteria for CIRCI during the 48 hours following intubation, compared to the subjects given an alternative induction agent. In our sample, all subjects with CIRCI were at an increased risk for mortality, compared to subjects without CIRCI.

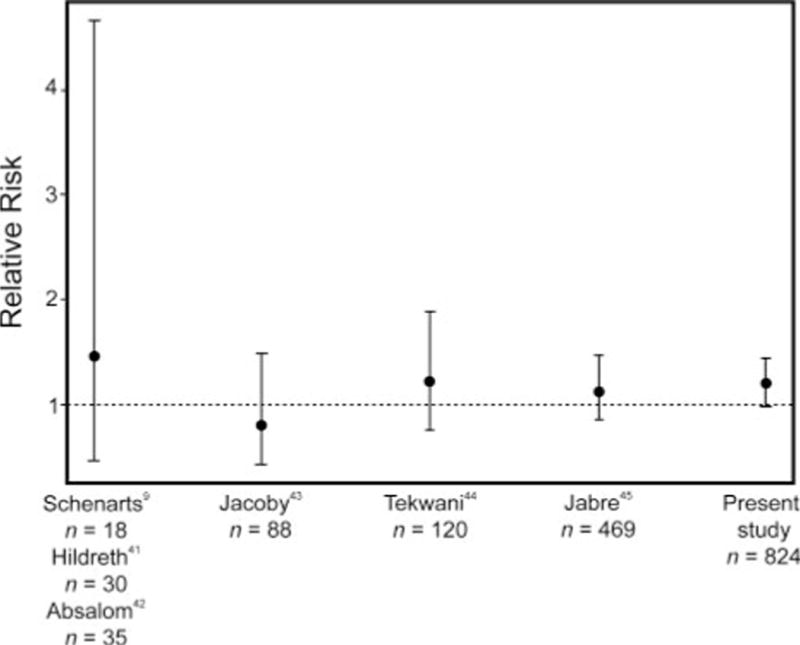

Our results should not be viewed in isolation. Rather, they should be viewed as a complement to those obtained in randomized trials, which generally observed a similarsized trend of increased mortality among recipients of etomidate (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Risk of mortality associated with etomidate administered to critically ill patients: results of 6 randomized controlled trials and the present cohort study.

There are limitations to our study. Potential confounding by indication is an important consideration25 given that patients who were hemodynamically unstable (and therefore potentially more likely to have died during admission) may preferentially have been given etomidate due to its favorable hemodynamic profile. Much effort was made to address this issue by means of adjustment. We tried to account for baseline illness severity using the SAPS II score and age. The SAPS II score is a strong predictor of the probability of hospital mortality.30 Nonetheless, despite the trend toward mortality we observed, the possibility of residual confounding as the basis for some or all of the observed relationship cannot be ruled out. In addition, some patients (about 15%, based on a review of a random sub-sample of records) to whom etomidate had been administered had an earlier intubation in which another agent had been used. During the records abstraction process such subjects were categorized as etomidate recipients only. Because in the sub-sample there were no deaths, it is likely that this method of categorization led to a somewhat low estimate of the relative mortality associated with receipt of etomidate. In addition, because data on steroid utilization were not available, we could not evaluate the possible influence of steroid administration on the association between etomidate and mortality.

Among patients undergoing mechanical ventilation, there have been 2 large randomized trials, and 4 with smaller sample sizes, that investigated mortality in relation to choice of induction agent.9,41,43–45 In the largest study to date, Jabre et al compared etomidate to ketamine in 469 patients and observed a slight—but statistically insignificant—increase in mortality among etomidate recipients (relative risk 1.12, 95% CI 0.87–1.46).45 Tekwani et al (n = 120) found that the relative risk of mortality was 1.19 (95% CI 0.76–1.87), comparing patients randomized to etomidate to patients given midazolam.44

A number of observational studies have also noted a small trend toward an increased risk of mortality in patients who are exposed to etomidate. A post hoc analysis of the CORTICUS study (n = 499), which randomized patients to corticosteroids or placebo (ie, not etomidate), observed that subjects who received etomidate before randomization were at an increased risk of subsequent mortality.19

In a planned, observational sub-study of the CORTICUS study, Cuthbertson and colleagues found that there was a relationship between etomidate exposure and subsequent mortality, and the relationship varied marginally depending on the model they used.16 Some have pointed out that the different findings of the models underscore the uncertainty of the relationship between etomidate and mortality.46 However, the 2 models’ adjusted estimates of mortality (which included different covariates) were comparable (OR 1.75, 95% CI 1.06–2.90 and OR 1.60, 95% CI 0.98–2.62), indicating that there is a reasonable probability of increased risk for mortality in those receiving etomidate.16 Moreover, the adjusted risk estimates likely would have been larger had the authors not controlled for levels of total serum cortisol and responsiveness to cosyntropin, both of which were measured after etomidate administration. Indeed, both of these measures are in the causal pathway of etomidate’s presumed relationship with mortality (via adrenal suppression) and thus they do not meet the classic definition of confounders.

It is important to note that some retrospective studies have not observed detrimental effects of etomidate induction in critically ill patients.46–48 In studies by Dmello et al (n = 224) and Riché et al (n = 118), the authors observed no differences in mortality among septic shock patients receiving etomidate, compared to those receiving alternative agents.46,47 Of note in these otherwise well conducted studies, the authors also observed no differences in adrenal function between their etomidate and non-etomidate groups, a finding at considerable odds with what has been shown in previous prospective studies.

Building on the work of Hohl and colleagues,18 Albert et al conducted a meta-analysis combining data from randomized and non-randomized studies.49 In aggregate, this study did find an increase in mortality risk among etomidate recipients, compared to non-recipients. However, interpreting effect sizes with pooled results from randomized and non-randomized studies should be done with great caution, given the unequal potential for confounding in the 2 different designs.

Collectively, these results provide evidence questioning the safety of etomidate in the setting of critical illness. To the extent that there are reasonable alternatives to etomidate in critically ill patients, evidence of multiple trends toward increased risk of mortality in etomidate recipients becomes important, given how commonly death occurs in this population. Assuming the mortality experience we observed is typical, and the relative risk truly is 1.20, then there would be a 6.2/100 patients absolute difference in mortality between etomidate recipients and patients receiving an alternative induction agent. In our sample, that equates to a number-needed-to-treat with an alternative induction agent to prevent one death of 16.1.

Conclusions

This cohort study and several smaller randomized trials observed a modest trend toward a relative increase in mortality in critically ill subjects requiring mechanical ventilation, among those given etomidate, compared to subjects given another induction agent. If this relationship is true, the potential absolute increase in mortality would be substantial in a population with high hospital mortality.

QUICK LOOK.

Current knowledge

In critically ill patients, induction with etomidate is hypothesized to be associated with an increased risk of mortality. Randomized trials have suggested a modest trend toward harm in etomidate recipients; however, these studies have lacked statistical precision due to sample size.

What this paper contributes to our knowledge

In critically ill patients requiring endotracheal intubation and in whom adrenal function was assessed (n=824), etomidate administration was associated with a trend toward higher mortality. If this small relative risk is true, in absolute terms, the number of deaths associated with etomidate in this high-risk population would be considerable. A large, prospective, controlled trial is needed to determine the role of etomidate in critically ill patients.

Acknowledgments

This research was partly supported by National Institute of Health Translational Science Award TL1RR025016.

Footnotes

The authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Benson M, Junger A, Fuchs C, Quinzio L, Böttger S, Hempelmann G. Use of an anesthesia information management system (AIMS) to evaluate the physiologic effects of hypnotic agents used to induce anesthesia. J Clin Monit Comput. 2000;16(3):183–190. doi: 10.1023/a:1009937510028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Guldner G, Schultz J, Sexton P, Fortner C, Richmond M. Etomidate for rapid-sequence intubation in young children: hemodynamic effects and adverse events. Acad Emerg Med. 2003;10(2):134–139. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2003.tb00030.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sokolove PE, Price DD, Okada P. The safety of etomidate for emergency rapid sequence intubation of pediatric patients. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2000;16(1):18–21. doi: 10.1097/00006565-200002000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zed PJ, Abu-Laban RB, Harrison DW. Intubating conditions and hemodynamic effects of etomidate for rapid sequence intubation in the emergency department: an observational cohort study. Acad Emerg Med. 2006;13(4):378–383. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2005.11.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fuchs-Buder T, Sparr HJ, Ziegenfuss T. Thiopental or etomidate for rapid sequence induction with rocuronium. Br J Anaesth. 1998;80(4):504–506. doi: 10.1093/bja/80.4.504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cohan P, Wang C, McArthur DL, Cook SW, Dusick JR, Armin B, et al. Acute secondary adrenal insufficiency after traumatic brain injury: a prospective study. Crit Care Med. 2005;33(10):2358–2366. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000181735.51183.a7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brinker den M, Joosten KF, Liem O, de Jong FH, Hop WC, Hazelzet JA, et al. Adrenal insufficiency in meningococcal sepsis: bioavailable cortisol levels and impact of interleukin-6 levels and intubation with etomidate on adrenal function and mortality. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90(9):5110–5117. doi: 10.1210/jc.2005-1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jackson WL. Should we use etomidate as an induction agent for endotracheal intubation in patients with septic shock? A critical appraisal. Chest. 2005;127(3):1031–1038. doi: 10.1378/chest.127.3.1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schenarts CL, Burton JH, Riker RR. Adrenocortical dysfunction following etomidate induction in emergency department patients. Acad Emerg Med. 2001;8(1):1–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2001.tb00537.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wagner RL, White PF, Kan PB, Rosenthal MH, Feldman D. Inhibition of adrenal steroidogenesis by the anesthetic etomidate. N Engl J Med. 1984;310(22):1415–1421. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198405313102202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.de Jong FH, Mallios C, Jansen C, Scheck PA, Lamberts SW. Etomidate suppresses adrenocortical function by inhibition of 1 l-hydroxylation. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1984;59(6):1143–1147. doi: 10.1210/jcem-59-6-1143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Duthie DJ, Fraser R, Nimmo WS. Effect of induction of anaesthesia with etomidate on corticosteroid synthesis in man. Br J Anaesth. 1985;57(2):156–159. doi: 10.1093/bja/57.2.156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kwon YS, Kang E, Suh GY, Koh WJ, Chung MP, Kim H, et al. A prospective study on the incidence and predictive factors of relative adrenal insufficiency in Korean critically ill patients. J Korean Med Sci. 2009;24(4):668–673. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2009.24.4.668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.de Jong MF, Beishuizen A, Spijkstra JJ, Girbes AR, Groeneveld AB. Relative adrenal insufficiency: an identifiable entity in nonseptic critically ill patients? Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2007;66(5):732–739. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2007.02814.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Annane D, Sébille V, Troché G, Raphaël JC, Gajdos P, Bellissant E. A 3-level prognostic classification in septic shock based on cortisol levels and cortisol response to corticotropin. JAMA. 2000;283(8):1038–1045. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.8.1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cuthbertson BH, Sprung CL, Annane D, Chevret S, Garfield M, Goodman S, et al. The effects of etomidate on adrenal responsiveness and mortality in patients with septic shock. Intensive Care Med. 2009;35(11):1868–1876. doi: 10.1007/s00134-009-1603-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rivers EP, Gaspari M, Saad GA, Mlynarek M, Fath J, Horst HM, Wortsman J. Adrenal insufficiency in high-risk surgical ICU patients. Chest. 2001;119(3):889–896. doi: 10.1378/chest.119.3.889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hohl CM, Kelly-Smith CH, Yeung TC, Sweet DD, Doyle-Waters MM, Schulzer M. The effect of a bolus dose of etomidate on cortisol levels, mortality, and health services utilization: a systematic review. Ann Emerg Med. 2010;56(2):105–113e5. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2010.01.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sprung CL, Annane D, Keh D, Moreno R, Singer M, Freivogel K, et al. Hydrocortisone therapy for patients with septic shock. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(2):111–124. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa071366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Warner KJ, Cuschieri J, Jurkovich GJ, Bulger EM. Single-dose etomidate for rapid sequence intubation may impact outcome after severe injury. J Trauma. 2009;67(1):45–50. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3181a92a70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hardcastle T. Avoiding etomidate for emergency intubation: throwing the baby out with the bathwater? S Afr J Crit Care. 2008;24(1):13–25. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Majesko A, Darby JM. Etomidate and adrenal insufficiency: the controversy continues. Crit Care. 2010;14(6):338. doi: 10.1186/cc9338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Annane D, Sébille V, Charpentier C, Bollaert PE, François B, Korach JM, et al. Effect of treatment with low doses of hydrocortisone and fludrocortisone on mortality in patients with septic shock. JAMA. 2002;288(7):862–871. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.7.862. Erratum in: JAMA 2008;300(14):1652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dellinger RP, Carlet JM, Masur H, Gerlach H, Calandra T, Cohen J, et al. Surviving Sepsis Campaign guidelines for management of severe sepsis and septic shock. Crit Care Med. 2004;32(3):858–873. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000117317.18092.e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Psaty BM, Siscovick DS. Minimizing bias due to confounding by indication in comparative effectiveness research: the importance of restriction. JAMA. 2010;304(8):897–898. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Koepsell TD, Weiss NS. Epidemiologic methods: studying the occurrence of illness. Oxford University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Marik PE, Pastores SM, Annane D, Meduri GU, Sprung CL, Arit W, et al. Recommendations for the diagnosis and management of corticosteroid insufficiency in critically ill adult patients: consensus statements from an international task force by the American College of Critical Care Medicine. Crit Care Med. 2008;36(6):1937–1949. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31817603ba. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang J, Yu K. What’s the relative risk? A method of correcting the odds ratio in cohort studies of common outcomes. JAMA. 1998;280(19):1690–1691. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.19.1690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lumley T, Ma S, Kronmal R. Relative risk regression in medical research: models, contrasts, estimators, and algorithms. UW Biostat Work Paper Series. 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Le Gall JR, Lemeshow S, Saulnier F. A new Simplified Acute Physiology Score (SAPS II) based on a European/North American multicenter study. JAMA. 1993;270(24):2957–2963. doi: 10.1001/jama.270.24.2957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hamrahian AH, Oseni TS, Arafah BM. Measurements of serum free cortisol in critically ill patients. N Engl J Med. 2004;350(16):1629–1638. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa020266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Khan T, Kupfer Y, Tessler S. Free cortisol and critically ill patients. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(4):395–397. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200407223510419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Arafah BM. Hypothalamic pituitary adrenal function during critical illness: limitations of current assessment methods. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91(10):3725–3745. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-0674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cohen J, Ward G, Prins J, Jones M, Venkatesh B. Variability of cortisol assays can confound the diagnosis of adrenal insufficiency in the critically ill population. Intensive Care Med. 2006;32(11):1901–1905. doi: 10.1007/s00134-006-0389-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Loisa P, Uusaro A, Ruokonen E. A single adrenocorticotropic hormone stimulation test does not reveal adrenal insufficiency in septic shock. Anesth Analg. 2005;101(6):1792–1798. doi: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000184042.91452.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cohen J, Venkatesh B. Relative adrenal insufficiency in the intensive care population; background and critical appraisal of the evidence. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2010;38(3):425–436. doi: 10.1177/0310057X1003800304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Venkatesh B, Mortimer RH, Couchman B, Hall J. Evaluation of random plasma cortisol and the low dose corticotropin test as indicators of adrenal secretory capacity in critically ill patients: a prospective study. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2005;33(2):201–209. doi: 10.1177/0310057X0503300208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bendel S, Karlsson S, Pettilä V, Loisa P, Varpula M, Ruokonen E, Finnsepsis Study Group Free cortisol in sepsis and septic shock. Anesth Analg. 2008;106(6):1813–1819. doi: 10.1213/ane.0b013e318172fdba. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brookhart MA, Schneeweiss S, Rothman KJ, Glynn RJ, Avorn J, Stürmer T. Variable selection for propensity score models. Am J Epidemiol. 2006;163(12):1149–1156. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwj149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vincent JL, de Mendonça A, Cantraine F, Moreno R, Takala J, Suter PM, et al. Use of the SOFA score to assess the incidence of organ dysfunction/failure in intensive care units: results of a multicenter, prospective study. Working group on “sepsis-related problems” of the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine. Crit Care Med. 1998;26(11):1793–1800. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199811000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hildreth AN, Mejia VA, Maxwell RA, Smith PW, Dart BW, Barker DE. Adrenal suppression following a single dose of etomidate for rapid sequence induction: a prospective randomized study. J Trauma. 2008;65(3):573–579. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e31818255e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Absalom A, Pledger D, Kong A. Adrenocortical function in critically ill patients 24 h after a single dose of etomidate. Anaesthesia. 1999;54(9):861–867. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2044.1999.01003.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jacoby J, Heller M, Nicholas J, Patel N, Cesta M, Smith G, et al. Etomidate versus midazolam for out-of-hospital intubation: a prospective, randomized trial. Ann Emerg Med. 2006;47(6):525–530. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2005.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tekwani KL, Watts HF, Sweis RT, Rzechula KH, Kulstad EB. A comparison of the effects of etomidate and midazolam on hospital length of stay in patients with suspected sepsis: a prospective, randomized study. Ann Emerg Med. 2010;56(5):481–489. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2010.05.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jabre P, Combes X, Lapostolle F, Dhaouadi M, Ricard-Hibon A, Vivien B, et al. KETASED Collaborative Study Group Etomidate versus ketamine for rapid sequence intubation in acutely ill patients: a multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2009;374(9686):293–300. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60949-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dmello D, Taylor S, O’Brien J, Matuschak GM. Outcomes of etomidate in severe sepsis and septic shock. Chest. 2010;138(6):1327–1332. doi: 10.1378/chest.10-0790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Riché FC, Boutron CM, Valleur P, Berton C, Laisné MJ, Launay JM, et al. Adrenal response in patients with septic shock of abdominal origin: relationship to survival. Intensive Care Med. 2007;33(10):1761–1766. doi: 10.1007/s00134-007-0770-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ray DC, McKeown DW. Effect of induction agent on vasopressor and steroid use, and outcome in patients with septic shock. Crit Care. 2007;11(3):R56. doi: 10.1186/cc5916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Albert SG, Ariyan S, Rather A. The effect of etomidate on adrenal function in critical illness: a systematic review. Intensive Care Med. 2011;37(6):901–910. doi: 10.1007/s00134-011-2160-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]