Abstract

Background

Antihypertensive drugs are used to control blood pressure (BP) and reduce macro- and microvascular complications in hypertensive patients with diabetes.

Objectives

The present study aimed to compare the functional vascular changes in hypertensive patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus after 6 weeks of treatment with amlodipine or losartan.

Methods

Patients with a previous diagnosis of hypertension and type 2 diabetes mellitus were randomly divided into 2 groups and evaluated after 6 weeks of treatment with amlodipine (5 mg/day) or losartan (100 mg/day). Patient evaluation included BP measurement, ambulatory BP monitoring, and assessment of vascular parameters using applanation tonometry, pulse wave velocity (PWV), and flow-mediated dilation (FMD) of the brachial artery.

Results

A total of 42 patients were evaluated (21 in each group), with a predominance of women (71%) in both groups. The mean age of the patients in both groups was similar (amlodipine group: 54.9 ± 4.5 years; losartan group: 54.0 ± 6.9 years), with no significant difference in the mean BP [amlodipine group: 145 ± 14 mmHg (systolic) and 84 ± 8 mmHg (diastolic); losartan group: 153 ± 19 mmHg (systolic) and 90 ± 9 mmHg (diastolic)]. The augmentation index (30% ± 9% and 36% ± 8%, p = 0.025) and augmentation pressure (16 ± 6 mmHg and 20 ± 8 mmHg, p = 0.045) were lower in the amlodipine group when compared with the losartan group. PWV and FMD were similar in both groups.

Conclusions

Hypertensive patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus treated with amlodipine exhibited an improved pattern of pulse wave reflection in comparison with those treated with losartan. However, the use of losartan may be associated with independent vascular reactivity to the pressor effect.

Keywords: Hypertension / complications; Diabetes Mellitus, Type 2 / complications; Atherosclerosis; Endothelium / physiopathology; Losartan / therapeutic, use; Amlodipine / therapeutic, use

Introduction

Systemic arterial hypertension (SAH) and type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) are often associated1. SAH induces vascular damage by promoting endothelial dysfunction and atherosclerosis. Early treatment of hypertension is particularly important in patients with diabetes to prevent cardiovascular disease (CVD) and to minimize the progression of kidney disease and diabetic retinopathy2.

Arterial stiffness has been recognized as a cardiovascular risk marker3. Patients with both SAH and T2DM exhibit increased arterial stiffness compared with those with either diabetes or hypertension4. Increased arterial stiffness is an important and independent risk factor associated with early mortality and assumes greater importance in clinical prognosis when compared with other known cardiovascular risk factors such as age, gender, smoking history, and dyslipidemia5. The gold standard for assessment of arterial stiffness is pulse wave velocity (PWV)6. An important parameter used to estimate arterial compliance is the augmentation index (AIx), which can be obtained using applanation tonometry7.

SAH, when associated with atherosclerosis and endothelial dysfunction, constitutes a risk factor that significantly increases cardiovascular morbidity and mortality8. Flow-mediated dilatation (FMD) of the brachial artery is a noninvasive method used to assess endothelial function. Using FMD, previous studies have indicated improved endothelial function in patients with hypertension, coronary artery disease, and heart failure who were treated with angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEIs)9,10 and in patients with diabetes treated with losartan11. The effects of amlodipine on endothelial function were evaluated in subjects with risk factors for coronary artery disease. Although, the subjects showed improvement in the parameters evaluated with FMD, this improvement was not significant when compared with the placebo group12.

The present study aimed to compare the functional vascular changes in hypertensive patients with T2DM after 6 weeks of use of a calcium channel antagonist (CCA; amlodipine) or an angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB; losartan).

Methods

Study sample

Patients with SAH and T2DM were selected for this study during clinical follow-up at the Pedro Ernesto University Hospital [Hospital Universitário Pedro Ernesto (HUPE)], State University of Rio de Janeiro. Patients of both sexes aged between 40 and 70 years who were diagnosed with SAH and T2DM, without changes in dietary treatment or oral medication usage in the last 4 weeks, were included in the study. The main exclusion criteria were signs of secondary hypertension, decompensated diabetes mellitus [fasting glucose levels of > 300 mg/dL or glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) levels of > 7%], need for insulin therapy, and chronic renal disease with an estimated glomerular filtration rate (GFR) of < 30 mL/min. The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of HUPE (protocol No. 20406/2012), and all participants read and signed the informed consent form.

After initial clinical and laboratory evaluation, the patients were randomized into 2 groups for treatment with either amlodipine (5 mg/day) or losartan (100 mg/day). After 6 weeks, a cross-sectional study involving analysis of clinical and laboratory data and performance of vascular tests was conducted.

Clinical evaluation

To determine blood pressure (BP), the patients remained seated for 30 min and refrained from using tobacco or caffeine. BP was evaluated using a semi-automatic calibrated device, model HEM-705CP (Omron Healthcare Inc., Illinois, USA), with the cuff adjusted for arm circumference. Three measurements were obtained in each upper limb, and the respective mean value was calculated. The highest mean value was used in data analysis.

With regard to anthropometric measurements, a precision scale (Filizola) with a maximum capacity of 180 kg was used to determine weight, and a stadiometer was used to measure height. The body mass index (BMI) was calculated by dividing the weight (in kilograms) by the squared height (in meters). Waist circumference was measured at the midpoint between the last rib and the iliac crest, and hip circumference was measured at the point of largest circumference in the gluteal region. The waist-hip ratio (WHR) was determined by dividing the values obtained for the respective circumferences.

Laboratory tests

For performance of biochemical tests and quantification of HbA1c levels using turbidimetry (BioSystems), venous blood samples were collected after fasting period of 10-12 h. GFR was estimated using the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease (MDRD) formula: GFRMDRD = 186 (serum creatinine)1.154 × (age)0.203 × [0.742 (if female) or 1.212 (if black)]13.

Serum lipids were analyzed using a colorimetric method (Bioclin). When the triglyceride level was 400 mg/dL, low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol was calculated using the Friedewald formula: LDL cholesterol = [total cholesterol − high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol] − (triglycerides/5). For quantitation of C-reactive protein (CRP), turbidimetry (BioSystems) was used, and the possibility of evaluating patients with acute infectious or inflammatory processes developed in recent weeks was excluded.

For evaluation of microalbuminuria, the urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio (UACR) was obtained from urine samples collected in the morning. Urine creatinine was quantitated using a colorimetric method, and albuminuria was determined using a nephelometric method.

Ambulatory blood pressure monitoring (ABPM)

ABPM was performed using the SpaceLabs 90207 device (SpaceLabs Inc., Redmond, WA, USA) scheduled to start between 8 and 9 am, with a minimum duration of 24 h. BP was measured every 20 min during the waking period (6 am-11 pm) and every 30 min during the sleeping period (11 pm-6 am). The test was considered satisfactory when at least 70% of the BP readings were valid, with a minimum of 16 readings during the waking period, 8 readings in the sleeping period, and a period < 2 h without BP measurements.

Vascular tests

Determination of the central aortic pressure

Pulse waves of the radial artery were obtained using an applanation tonometer (model SPC-301-Millar Instruments, Houston, Texas, USA), calibrated according to the brachial artery pressure. Pulse wave analysis was performed to obtain central arterial pressures and other hemodynamic parameters using the SphygmoCor system (Atcor, United States)14. Aortic pressure waves were subjected to several analyses to identify the time between the beginning and the first and second peaks of the arterial pulse wave during systole. The pressure difference between the first component and the maximum pressure at systole [pressure increase (PI)] was identified as the reflected pressure wave during systole. AIx was defined as the ratio between PI and central pulse pressure (PP); it was expressed as a percentage [AIx = (PI/PP) × 100] and was subsequently adjusted for a heart rate of 75 bpm (AIx@75).

Pulse wave velocity

Pulse waves were obtained via the transcutaneous route using a COMPLIOR SP device (Artech Medical), with transducers placed in the regions of the right carotid artery, right radial artery (peripheral PWV), and right femoral artery (central PWV)15. Two measurements were made during the same consultation, and when differences were > 10%, a third measurement was made. The mean of the 2 measurements was used for analysis. The measure was corrected for the mean arterial pressure (MAP) by using the formula PWV-N = (PWV/MAP) × 100.

Flow-mediated dilation of the brachial artery

This technique was performed using a 2-dimensional ultrasound device with color and spectral Doppler (Vivid-3, GE, United States) and a linear transducer with a frequency of 10 MHz. The patients were placed in supine position with the right arm slightly stretched. After the brachial artery was located, the transducer was placed on the anteromedial side of the right upper limb, perpendicular to the arm axis and 5-10 cm above the antecubital fold in the region of the brachial artery. The basal brachial artery diameter (BBAD) and post-occlusion brachial artery diameter (POBAD) were measured manually between the lumen-intima interfaces at end-diastole. After BBAD measurement, the site of contact of the probe on the skin was marked to allow POBAD measurement at the same site. Flow occlusion was maintained for 5 min using an arm cuff, allowing the recording of a BP of 60 mmHg above the systolic arterial pressure. POBAD was measured at 30, 60, and 90 s after blood flow release16. The tests were performed by the same examiner who was unaware of the data recorded. FMD was calculated as the percentage increase in POBAD compared with baseline values using the following formula: FMD (%) = (POBAD − BBAD/BBAD) × 100.

Statistical Analysis

To calculate the sample size, the Sample Power module of the SPSS® software version 18.0 was used. By adopting a significance criterion (alpha) of 0.05, a minimum sample size of 16 patients was proposed for each group. After analyzing the changes in FMD of the brachial artery and based on the results of other clinical studies, the statistical significance power was determined as 80.7% and the accuracy was ± 1.44 points, using a 95% confidence interval11,12.

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS® software version 18.0. The results were expressed as the mean ± standard deviation or as absolute and percentage values. The continuous variables of each group were compared using unpaired Student's t test between groups with a 95% confidence interval. A p-value of < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

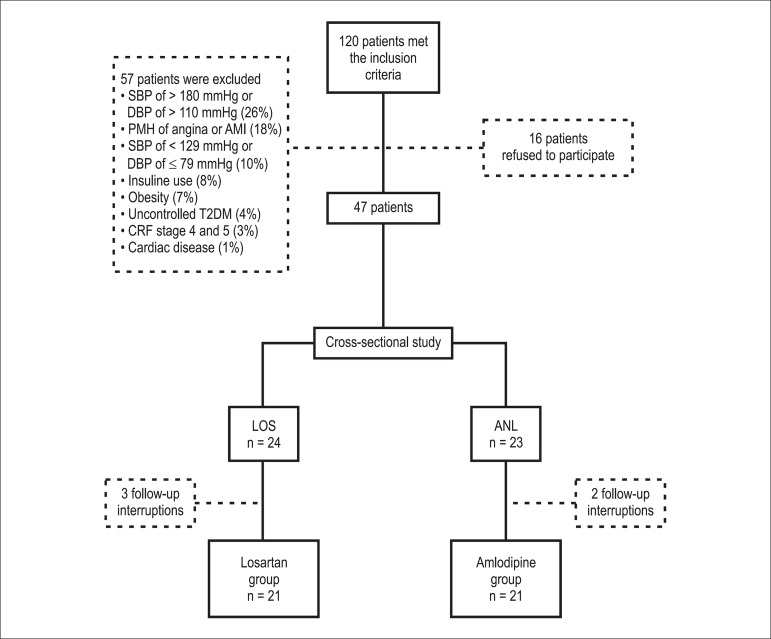

Initially, 120 hypertensive patients with diabetes who met the inclusion criteria were selected. Among these, 73 (61%) met the exclusion criteria and were withdrawn from the study. Accordingly, 47 subjects were included in the study and were randomly divided into the losartan or amlodipine group. Because of 5 follow-up interruptions during the evaluation period, only 42 patients completed the study (21 in each group) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Patient selection flowchart. ANL: amlodipine; T2DM: type 2 diabetes mellitus; PMH: past medical history; CRF: chronic renal failure; LOS: losartan; DBP: diastolic blood pressure; SBP: systolic blood pressure.

The groups were evaluated and compared according to their clinical and epidemiological profiles, presence of cardiovascular risk factors, and prior use of medications. All patients were sedentary. A comparison between the 2 groups indicated no significant difference between the variables analyzed (Table 1).

Table 1.

Profile of each group evaluated and comparison between the variables analyzed

| Variables | Losartan group (n = 21) | Amlodipine group (n = 21) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 54.0 ± 6.9 | 54.9 ± 4.5 | 0.619 |

| Female, n (%) | 15 (71.4) | 15 (71.4) | 1.000 |

| Black, n (%) | 4 (19.0) | 3 (14.3) | 0.679 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 30.4 ± 3.5 | 29.8 ± 4.0 | 0.636 |

| Smoking, n (%) | 5 (23.8) | 6 (28.6) | 0.939 |

| Dyslipidemia, n (%) | 13 (61.9) | 12 (57.1) | 0.753 |

| Statin use, n (%) | 8 (38.1) | 6 (28.6) | 0.513 |

| ASA use, n (%) | 7 (33.3) | 7 (33.3) | 1.000 |

| Metformin use, n (%) | 18 (85.7) | 18 (85.7) | 1.000 |

| Sulfonylurea use, n (%) | 5 (23.8) | 6 (28.6) | 0.726 |

Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation or as percentages, as indicated. ASA: acetylsalicylic acid; BMI: body mass index. The p-values were calculated using Student's t test for continuous variables and the chi-square test for categorical variables.

The initial BP values were calculated in each group for the determination of systolic blood pressure (SBP) and diastolic blood pressure (DBP). Mean SBP and DBP were 147 ± 11 mmHg and 85 ± 9 mmHg, respectively, in the losartan group and 147 ± 21 mmHg and 84 ± 8 mmHg, respectively, in the amlodipine group.

Table 2 shows the laboratory profiles, estimated GFRs using MDRD, and UACR. Mean microalbuminuria was lower in the amlodipine group when compared with the losartan group; however, the difference was not significant. In the losartan group, 33% of patients presented with microalbuminuria, with a mean value of 81.3 mg/g creatinine; in the amlodipine group, 24% of patients presented with microalbuminuria, with a mean value of 57.3 mg/g creatinine.

Table 2.

Laboratory profile of the study population

| Variables | Losartan group (n = 21) | Amlodipine group (n = 21) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Creatinine, mg/dL | 0.7 ± 0.2 | 0.7 ± 0.2 | 0.577 |

| Potassium, mEq/L | 4.3 ± 0.4 | 4.3 ± 0.5 | 0.684 |

| Blood glucose, mg/dL | 111.7 ± 43.0 | 122.0 ± 47.8 | 0.467 |

| HbA1c, % total Hb | 6.2 ± 0.5 | 6.4 ± 0.5 | 0.270 |

| Total cholesterol, mg/dL | 196.4 ± 35.6 | 191.9 ± 30.0 | 0.662 |

| HDL cholesterol, mg/dL | 55.1 ± 19.5 | 55.0 ± 12.1 | 0.985 |

| LDL cholesterol, mg/dL | 115.9 ± 40.1 | 111.6 ± 27.1 | 0.585 |

| Triglycerides, mg/dL | 127.3 ± 48.0 | 127.0 ± 56.4 | 0.984 |

| CRP, mg/dL | 0.3 ± 0.3 | 0.5 ± 0.5 | 0.393 |

| GRFMDRD, mL/min/1, 73 m2 | 91.9 ± 21.4 | 100.0 ± 34.6 | 0.368 |

| UACR, mg/g creatinine | 34.6 ± 40.1 | 24.8 ± 25.9 | 0.352 |

Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation. Hb: hemoglobin; HbA1c: glycated hemoglobin; HDL: high-density lipoprotein; LDL: low-density lipoprotein; CRP: C-reactive protein; MDRD: Modification of Diet in Renal Disease; UACR: urinary albumin-to-creatinine ratio; GFR: glomerular filtration rate. The p-values were calculated using Student's t test.

After 6 weeks of treatment, the losartan and amlodipine groups no significant differences in SBP (153 ± 19 mmHg and 145 ± 14 mmHg, respectively, p = 0.127), and DBP (90 ± 9 mmHg and 84 ± 8 mmHg, respectively, p = 0.063), although the values were slightly lower in the amlodipine group. The data obtained with ABPM after treatment with losartan or amlodipine revealed no significant differences between the 2 groups, and similar results were obtained during the waking and sleeping periods (Table 3).

Table 3.

Data obtained with ambulatory blood pressure monitoring

| Variables | Losartan group (n = 21) | Amlodipine group (n = 21) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| SBP in 24 h, mmHg | 136 ± 14 | 137 ± 14 | 0.947 |

| DBP in 24 h, mmHg | 81 ± 11 | 82 ± 9 | 0.892 |

| MAP in 24 h, mmHg | 100 ± 12 | 101 ± 10 | 0.888 |

| SBP during the waking period, mmHg | 139 ± 15 | 139 ± 14 | 0.888 |

| DBP during the waking period, mmHg | 84 ± 12 | 85 ± 10 | 0.787 |

| MAP during the waking period, mmHg | 103 ± 12 | 104 ± 10 | 0.836 |

| SBP during the sleeping period, mmHg | 132 ± 15 | 131 ± 16 | 0.846 |

| DBP during the sleeping period, mmHg | 75 ± 12 | 75 ± 9 | 0.942 |

| MAP during the sleeping period, mmHg | 95 ± 13 | 94 ± 10 | 0.893 |

Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation. DBP: diastolic blood pressure; SBP: systolic blood pressure; MAP: mean arterial pressure. The p-values were calculated using Student's t test.

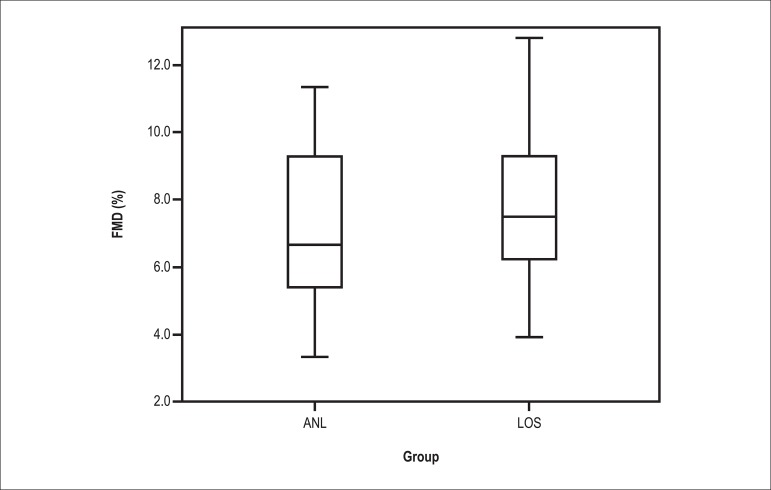

The PWV results revealed no significant differences between the 2 treatment groups. In contrast, applanation tonometry data indicated that the mean augmentation pressure was significantly higher in the losartan group in comparison with the amlodipine group (20 ± 8 mmHg and 16 ± 6 mmHg, respectively, p = 0.045). Similarly, a significantly higher mean AIx was observed in the losartan group when compared with the amlodipine group (36% ± 8% and 30% ± 9%, respectively, p = 0.025, Table 4). Increased endothelial function was observed in the losartan group using FMD (8.4% ± 4.6% and 7.5% ± 3.0%, respectively p = 0.431); however, the difference was not significant between the 2 groups (Figure 2).

Table 4.

Values obtained with pulse wave velocity and applanation tonometry

| Variables | Losartan group (n = 21) | Amlodipine group (n = 21) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| CR-PWV, m/s | 9.9 ± 1.1 | 9.5 ± 1.4 | 0.347 |

| CF-PWV, m/s | 10.4 ± 2.2 | 10.6 ± 2.7 | 0.880 |

| NCF-PWV, m/s | 9.5 ± 1.8 | 9.8 ± 2.5 | 0.595 |

| ASBP, mmHg | 144 ± 19 | 136 ± 12 | 0.108 |

| ADBP, mmHg | 90 ± 10 | 84 ± 10 | 0.100 |

| PI, mmHg | 20 ± 8 | 16 ± 6 | 0.045 |

| AIx, % | 36 ± 8 | 30 ± 9 | 0.025 |

| APP, mmHg | 53 ± 16 | 49 ± 11 | 0.386 |

| AIx@75, % | 32 ± 7 | 28 ± 7 | 0.050 |

Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation. AIx: augmentation index; AP: augmentation pressure; AIx@75: augmentation index corrected for a heart rate of 75 bpm; ADBP: aortic diastolic blood pressure; ASBP: aortic systolic blood pressure; APP: aortic pulse pressure; CF-PWV: carotid-femoral pulse wave velocity; NCF-PWV: normalized carotid-femoral pulse wave velocity; CR-PWV: carotid-radial pulse wave velocity. The p-values were calculated using Student's t test.

Figure 2.

Distribution of values of flow-mediated dilation (FMD) of the brachial artery in the amlodipine (ANL) and losartan (LOS) group; p = 0.431 using Student's t test.

Discussion

This cross-sectional study aimed to evaluate cardiovascular risk markers, including arterial stiffness and endothelial dysfunction, in a group of hypertensive patients with T2DM after 6 weeks of treatment with an ARB or a CCA, which are important antihypertensive drugs currently used in the treatment of such patients. Diabetes mellitus increases the risk of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in patients with hypertension by 2- to 3-fold, and a decline in BP can decrease the rate of cardiovascular events and renal impairment in these patients17. However, it is unclear whether all classes of antihypertensive drugs play a similar role in the treatment of hypertensive patients with diabetes and can lead to alterations in cardiovascular risk markers.

A comparison between the 2 groups at the beginning of the study indicated similarities in their clinical and epidemiological profiles, presence of cardiovascular risk factors, and previous use of medications. Furthermore, the initial antihypertensive treatment performed was similar between the 2 groups, eliminating the difference in treatment as a confounding factor in the interpretation of the results.

Glucose and lipid metabolism, serum potassium levels, and microalbuminuria were also evaluated, although assessment of these parameters was not the primary aim of this study. In the study by Otero et al18, improved glycaemia and HbA1c levels were reported in patients treated with manidipine when compared with those treated with enalapril. In contrast, Derosa et al19 found no difference in blood glucose levels between patients who received telmisartan or nifedipine, whereas Nishida et al20 observed better HbA1c levels in patients who received ARBs when compared with those who received CCAs. In another study, Giordano et al21 obtained similar results for blood glucose and HbA1c levels in patients on captopril or nifedipine. In the present study, the mean blood glucose levels were higher in the amlodipine group than in the losartan group; however, the difference was not significant. In contrast, HbA1c levels were similar between the 2 groups. Moreover, no difference was found between the 2 groups regarding the use of hypoglycemic agents. In view of these findings, little can be inferred about the influence of ARBs or CCAs on glycemic control.

In the present study, we found no significant difference in mean serum potassium levels between the losartan and amlodipine groups. These results are in contrast with those obtained by Nishida et al20, who reported higher levels in patients using ARBs than in those using CCAs. With regard to lipid metabolism, the levels of total cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, and triglycerides were similar between the 2 groups. In the study conducted by Derosa et al19, lower values of total cholesterol and LDL cholesterol were found in patients treated with telmisartan compared with those treated with nifedipine. These results are similar to those obtained by Nishida et al20, who compared patients using ARBs and those using CCAs, thereby suggesting that ARBs may have improved benefits on lipid metabolism in comparison with CCAs.

Microalbuminuria was determined by calculating UACR. Mean microalbuminuria was lower in the amlodipine group in comparison with the losartan group; however, the difference was not significant. The profile of the evaluated study group indicated a decreased risk of nephropathy. Because of its cross-sectional nature, the present study did not evaluate the effects of each drug on the variables analyzed, including microalbuminuria. In contrast, Yasuda et al22 conducted a prospective study comparing patients on losartan or amlodipine and found lower microalbuminuria in the losartan group. The authors of the IDNT study23 evaluated patients with SAH and nephropathy secondary to T2DM; as primary outcomes, they observed a lower risk of renal function impairment in patients who received irbesartan when compared with those who received amlodipine or placebo. However, there was no significant difference in the risk of all-cause death, even in subjects with renal function impairment. Moreover, the RENAAL study24 evaluated the effects of losartan on renal and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with T2DM and nephropathy compared with the placebo group and found a decrease in the progression of renal disease in the losartan group. However, no decrease in nephropathy- and CVD-related mortality was observed. In contrast, Yilmaz et al25 compared the use of valsartan, amlodipine, or a combination of these drugs in patients with hypertension and T2DM and observed decreased microalbuminuria in the 3 patient groups. These findings suggest that although CCAs do not have the same effects as ARBs on kidney hemodynamics, CCAs may have an important role in reducing microalbuminuria in patients with hypertension and diabetes, which can be explained by their antihypertensive efficacy.

After 6 weeks of treatment with losartan or amlodipine, lower mean BP levels were observed in the amlodipine group in comparison with the losartan group, although the differences were not significant. The Valsartan Antihypertensive Long-term Use Evaluation (VALUE) trial26 compared patients with hypertension who were treated with valsartan or amlodipine and revealed an increased control of BP in patients treated with amlodipine. Two years later, Zanchetti et al27 performed further analysis of the VALUE trial data according to subgroups and indicated improved BP control in the group treated with amlodipine compared with the group treated with valsartan; furthermore, this reduction was more pronounced in women. Phillips et al28 compared patients with hypertension who were treated with amlodipine or losartan and found a decrease in BP in both groups; however, this decrease was greater in the group receiving amlodipine.

Previous studies have evaluated patients with hypertension and diabetes treated using CCAs and compared them with those using ARBs or ACEIs. Derosa et al19 compared the use of telmisartan or amlodipine, revealing similarities between the 2 drugs in the ability to decrease BP; no significant difference was found between the treatment groups. Yasuda et al22 studied the effects of losartan and amlodipine on BP in patients with hypertension and diabetes and reported that both drugs were capable of reducing BP levels; no significant difference was found between these 2 groups. Similarly, Miyashita et al29 compared the effects of olmesartan and amlodipine on BP and found similar results between the 2 drugs.

In the present study, the mean BP values obtained with ABPM were similar in both groups, consistent with the results reported by Yasuda et al22 when comparing the effects of losartan and amlodipine on BP. Ishimitsu et al30 studied the effects of losartan in hypertensive patients without diabetes in comparison with patients receiving amlodipine and reported that both drugs were able to decrease BP over 24 h; however, the effects of amlodipine were greater than those of losartan. Otero et al18 used ABPM to evaluate BP in patients with hypertension and diabetes treated with manidipine or enalapril and found no differences between these 2 drug classes.

SAH is associated with the pathogenesis of arterial stiffness and is a manifestation of decreased arterial compliance31. Decrease in mean BP levels, and consequently in the pressure distension on blood vessels, is the greatest beneficial effect common to all classes of antihypertensive drugs31. In this context, growing evidence indicates the beneficial effects of CCAs and other drugs that interfere with the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) for the management of important hemodynamic parameters31. After conducting a meta-analysis comparing ACEIs and ARBs with CCAs, diuretics, and beta blockers, Boutouyrie et al32 reported the improved ability of ACEIs and ARBs in decreasing PWV and AIx. Kim et al33 evaluated 98 patients with hypertension and T2DM after 12 weeks of use of valsartan and found a decrease in aortic pulse pressure (APP), AIx, and PWV. Similarly, Asmar et al34 studied a group of 28 patients with hypertension and T2DM who were treated with telmisartan and found a decrease in PWV and AIx in these patients compared with the placebo group.

Kita et al35 evaluated 29 patients hypertension treated with benidipine for 1 year and found a decrease in PWV in these patients. Previous studies have compared the effects of drugs that affect RAAS with CCAs. Rajzer et al36 evaluated 180 patients with hypertension who were randomized into 3 groups according to the drug administered [quinapril (20 mg/day), amlodipine (10 mg/day), and losartan (100 mg/day)] and reported that all 3 drugs were able to decrease BP. However, only the quinapril group exhibited a significant decrease in PWV. Moreover, Ichihara et al37 compared the effects of amlodipine with those of valsartan on PWV. The study monitored 100 patients with hypertension for 1 year and indicated a similar decrease in PWV in the 2 groups.

In the present study, applanation tonometry results revealed lower mean values of systolic and diastolic central aortic pressure, AIx, PI, and APP in the amlodipine group when compared with the losartan group. These findings suggest an improved pattern of pulse wave reflection in the amlodipine group. The results obtained with ABPM indicated no differences in the final BP in both groups, which corroborates these important hemodynamic findings. The average BP values over 24 h indicate an improved control of BP in hypertensive subjects. The lowest casual BP observed in the amlodipine group appears to reflect a more pronounced acute effect of the CCA in comparison with the ARB. With regard to PWV, the results were similar in both groups and indicated no significant differences in arterial stiffness.

In the present, FMD was used to assess endothelial dysfunction. Some previous studies have also reported the effect of antihypertensive drugs on FMD. Cheetham et al11 compared the efficacy of losartan (50 mg/day) for 4 weeks with that of placebo in 12 hypertensive patients with T2DM. The results indicated a significant increase in FMD in the losartan group. Clarkson et al12 compared the efficacy of amlodipine (5 mg/day) with that of placebo in 91 patients with hypertensive. A significant increase in FMD was observed in both groups. However, no significant differences between the groups could indicate the superiority of one intervention over the other. Another study conducted by Anderson et al38 evaluated the effects of 3 classes of drugs on FMD in 80 patients who were randomized into 4 groups according to the treatment received: enalapril (10 mg/day), quinapril (20 mg/day), losartan (50 mg/day), and amlodipine (5 mg/day). After 8 weeks, only quinapril resulted in a significant increase in FMD. Yilmaz et al25 compared the effect of amlodipine (10 mg/day), valsartan (160 mg/day), or a combination of these 2 drugs on FMD. They observed that all treatment regimens effectively increased FMD, and the largest increase was observed in the group treated with the drug combination. In the present study, the mean percentage increase in FMD was higher in the losartan group compared with the amlodipine group. However, this difference was not significant, thereby preventing further conclusions in the evaluation of this method.

Conclusions

In hypertensive patients with T2DM with no evidence of advanced nephropathy, treatment with amlodipine at an average dose resulted in similar BP levels in a 24-h period when compared with treatment with losartan at the maximum dose. Assessment of functional vascular alterations revealed a more favorable pattern of pulse wave reflection in the amlodipine group when compared with the losartan group. The decreased casual BP levels in patients treated with amlodipine, although not significant, may have clinical importance. However, the other functional vascular parameters evaluated were similar in both groups, which may indicate the occurrence of vascular effects associated with the use of losartan, regardless of its antihypertensive effect.

Footnotes

Potential Conflict of Interest

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

Author contributions

Conception and design of the research and Analysis and interpretation of the data: Pozzobon CR, Neves MF, Oigman W; Acquisition of data: Pozzobon CR, Gismondi RAOC, Bedirian R, Ladeira MC, Neves MF; Statistical analysis: Pozzobon CR, Neves MF; Writing of the manuscript: Pozzobon CR; Critical revision of the manuscript for intellectual content: Pozzobon CR, Gismondi RAOC, Bedirian R, Neves MF, Oigman W.

Sources of Funding

There were no external funding sources for this study.

Study Association

This article is part of the thesis of master submitted by Cesar Romaro Pozzobon, from Universidade do Estado do Rio de Janeiro.

References

- 1.Williams B. The Hypertension in Diabetes Study (HDS): a catalyst for change. Diabet Med. 2008;25(Suppl 2):13–19. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2008.02506.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gaede P, Vedel P, Parving HH, Pedersen O. Intensified multifactorial intervention in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and microalbuminuria: the Steno type 2 randomised study. Lancet. 1999;353(9153):617–622. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)07368-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Adji A, O'Rourke MF, Namasivayam M. Arterial stiffness, its assessment, prognostic value, and implications for treatment. Am J Hypertens. 2011;24(1):5–17. doi: 10.1038/ajh.2010.192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tedesco MA, Natale F, Di Salvo G, Caputo S, Capasso M, Calabro R. Effects of coexisting hypertension and type II diabetes mellitus on arterial stiffness. J Hum Hypertens. 2004;18(7):469–473. doi: 10.1038/sj.jhh.1001690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Willum-Hansen T, Staessen JA, Torp-Pedersen C, Rasmussen S, Thijs L, Ibsen H, et al. Prognostic value of aortic pulse wave velocity as index of arterial stiffness in the general population. Circulation. 2006;113(5):664–670. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.579342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vlachopoulos C, Aznaouridis K, Stefanadis C. Prediction of cardiovascular events and all-cause mortality with arterial stiffness: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55(13):1318–1327. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.10.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Izzo JL J, editor. Hypertension primer. 4th. ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Contreras F, Rivera M, Vasquez J, De la Parte MA, Velasco M. Endothelial dysfunction in arterial hypertension. J Hum Hypertens. 2000;14(Suppl 1):S20–S25. doi: 10.1038/sj.jhh.1000982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mancini GB, Henry GC, Macaya C, O'Neill BJ, Pucillo AL, Carere RG, et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition with quinapril improves endothelial vasomotor dysfunction in patients with coronary artery disease. The TREND (Trial on Reversing ENdothelial Dysfunction) Study. Circulation. 1996;94(3):258–265. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.94.3.258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nakamura M, Funakoshi T, Arakawa N, Yoshida H, Makita S, Hiramori K. Effect of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors on endothelium-dependent peripheral vasodilation in patients with chronic heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1994;24(5):1321–1327. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(94)90115-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cheetham C, O'Driscoll G, Stanton K, Taylor R, Green D. Losartan, an angiotensin type I receptor antagonist, improves conduit vessel endothelial function in Type II diabetes. Clin Sci (Lond) 2001;100(1):13–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Clarkson P, Mullen MJ, Donald AE, Powe AJ, Thomson H, Thorne SA, et al. The effect of amlodipine on endothelial function in young adults with a strong family history of premature coronary artery disease: a randomised double blind study. Atherosclerosis. 2001;154(1):171–177. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9150(00)00455-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Levey AS, Bosch JP, Lewis JB, Greene T, Rogers N, Roth D. A more accurate method to estimate glomerular filtration rate from serum creatinine: a new prediction equation. Modification of Diet in Renal Disease Study Group. Ann Intern Med. 1999;130(6):461–470. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-130-6-199903160-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pauca AL, O'Rourke MF, Kon ND. Prospective evaluation of a method for estimating ascending aortic pressure from the radial artery pressure waveform. Hypertension. 2001;38(4):932–937. doi: 10.1161/hy1001.096106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Asmar R, Benetos A, Topouchian J, Laurent P, Pannier B, Brisac AM, et al. Assessment of arterial distensibility by automatic pulse wave velocity measurement. Validation and clinical application studies. Hypertension. 1995;26(3):485–490. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.26.3.485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Corretti MC, Anderson TJ, Benjamin EJ, Celermajer D, Charbonneau F, Creager MA, et al. Guidelines for the ultrasound assessment of endothelial-dependent flow-mediated vasodilation of the brachial artery: a report of the International Brachial Artery Reactivity Task Force. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;39(2):257–265. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(01)01746-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grossman E, Messerli FH. Are calcium antagonists beneficial in diabetic patients with hypertension? Am J Med. 2004;116(1):44–49. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2003.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Otero ML, Claros NM. Manidipine versus enalapril monotherapy in patients with hypertension and type 2 diabetes mellitus: a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, 24-week study. Clin Ther. 2005;27(2):166–173. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2005.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Derosa G, Cicero AF, Bertone G, Piccinni MN, Fogari E, Ciccarelli L, et al. Comparison of the effects of telmisartan and nifedipine gastrointestinal therapeutic system on blood pressure control, glucose metabolism, and the lipid profile in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and mild hypertension: a 12-month, randomized, double-blind study. Clin Ther. 2004;26(8):1228–1236. doi: 10.1016/s0149-2918(04)80049-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nishida Y, Takahashi Y, Nakayama T, Asai S. Comparative effect of angiotensin II type I receptor blockers and calcium channel blockers on laboratory parameters in hypertensive patients with type 2 diabetes. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2012;11:53. doi: 10.1186/1475-2840-11-53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Giordano M, Matsuda M, Sanders L, Canessa ML, DeFronzo RA. Effects of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, Ca2+ channel antagonists, and alpha-adrenergic blockers on glucose and lipid metabolism in NIDDM patients with hypertension. Diabetes. 1995;44(6):665–671. doi: 10.2337/diab.44.6.665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yasuda G, Ando D, Hirawa N, Umemura S, Tochikubo O. Effects of losartan and amlodipine on urinary albumin excretion and ambulatory blood pressure in hypertensive type 2 diabetic patients with overt nephropathy. Diabetes Care. 2005;28(8):1862–1868. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.8.1862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lewis EJ, Hunsicker LG, Clarke WR, Berl T, Pohl MA, Lewis JB, et al. Renoprotective effect of the angiotensin-receptor antagonist irbesartan in patients with nephropathy due to type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2001;345(12):851–860. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa011303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brenner BM, Cooper ME, de Zeeuw D, Keane WF, Mitch WE, Parving HH, et al. Effects of losartan on renal and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes and nephropathy. N Engl J Med. 2001;345(12):861–869. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa011161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yilmaz MI, Carrero JJ, Martin-Ventura JL, Sonmez A, Saglam M, Celik T, et al. Combined therapy with renin-angiotensin system and calcium channel blockers in type 2 diabetic hypertensive patients with proteinuria: effects on soluble TWEAK, PTX3, and flow-mediated dilation. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;5(7):1174–1181. doi: 10.2215/CJN.01110210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Julius S, Kjeldsen SE, Weber M, Brunner HR, Ekman S, Hansson L, et al. Outcomes in hypertensive patients at high cardiovascular risk treated with regimens based on valsartan or amlodipine: the VALUE randomised trial. Lancet. 2004;363(9426):2022–2031. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16451-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zanchetti A, Julius S, Kjeldsen S, McInnes GT, Hua T, Weber M, et al. Outcomes in subgroups of hypertensive patients treated with regimens based on valsartan and amlodipine: an analysis of findings from the VALUE trial. J Hypertens. 2006;24(11):2163–2168. doi: 10.1097/01.hjh.0000249692.96488.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Phillips RA, Kloner RA, Grimm RH, Jr, Weinberger M. The effects of amlodipine compared to losartan in patients with mild to moderately severe hypertension. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 2003;5(1):17–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-6175.2003.01416.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Miyashita Y, Saiki A, Endo K, Ban N, Yamaguchi T, Kawana H, et al. Effects of olmesartan, an angiotensin II receptor blocker, and amlodipine, a calcium channel blocker, on Cardio-Ankle Vascular Index (CAVI) in type 2 diabetic patients with hypertension. J Atheroscler Thromb. 2009;16(5):621–626. doi: 10.5551/jat.497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ishimitsu T, Minami J, Yoshii M, Suzuki T, Inada H, Ohta S, et al. Comparison of the effects of amlodipine and losartan on 24-hour ambulatory blood pressure in hypertensive patients. Clin Exp Hypertens. 2002;24(1-2):41–50. doi: 10.1081/ceh-100108714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Milan A, Tosello F, Fabbri A, Vairo A, Leone D, Chiarlo M, et al. Arterial stiffness: from physiology to clinical implications. High Blood Press Cardiovasc Prev. 2011;18(1):1–12. doi: 10.2165/11588020-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Boutouyrie P, Lacolley P, Briet M, Regnault V, Stanton A, Laurent S, et al. Pharmacological modulation of arterial stiffness. Drugs. 2011;71(13):1689–1701. doi: 10.2165/11593790-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kim JH, Oh SJ, Lee JM, Hong EG, Yu JM, Han KA, et al. The effect of an angiotensin receptor blocker on arterial stiffness in type 2 diabetes mellitus patients with hypertension. Diabetes Metab J. 2011;35(3):236–242. doi: 10.4093/dmj.2011.35.3.236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Asmar R, Gosse P, Topouchian J, N'Tela G, Dudley A, Shepherd GL. Effects of telmisartan on arterial stiffness in Type 2 diabetes patients with essential hypertension. J Renin Angiotensin Aldosterone Syst. 2002;3(3):176–180. doi: 10.3317/jraas.2002.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kita T, Suzuki Y, Eto T, Kitamura K. Long-term anti-hypertensive therapy with benidipine improves arterial stiffness over blood pressure lowering. Hypertens Res. 2005;28(12):959–964. doi: 10.1291/hypres.28.959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rajzer M, Klocek M, Kawecka-Jaszcz K. Effect of amlodipine, quinapril, and losartan on pulse wave velocity and plasma collagen markers in patients with mild-to-moderate arterial hypertension. Am J Hypertens. 2003;16(6):439–444. doi: 10.1016/s0895-7061(03)00052-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ichihara A, Kaneshiro Y, Takemitsu T, Sakoda M. Effects of amlodipine and valsartan on vascular damage and ambulatory blood pressure in untreated hypertensive patients. J Hum Hypertens. 2006;20(10):787–794. doi: 10.1038/sj.jhh.1002067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Anderson TJ, Elstein E, Haber H, Charbonneau F. Comparative study of ACE-inhibition, angiotensin II antagonism, and calcium channel blockade on flow-mediated vasodilation in patients with coronary disease (BANFF study) J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;35(1):60–66. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(99)00537-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]