Abstract

Background

End-of-life medical expenditures exceed costs during other periods, vary across regions, and are likely to be unsustainable. Identifying determinants of expenditure variation may reveal opportunities for reducing costs.

Objectives

To 1) identify patient-level determinants of Medicare expenditures at end-of-life and 2) determine these factors’ contributions to expenditure variation while accounting for regional characteristics. We hypothesized that race/ethnicity, social support and functional status are independently associated with treatment intensity, controlling for regional characteristics, and that individual characteristics account for a substantial proportion of expenditure variation.

Design

Using Health and Retirement Study (HRS), Medicare claims and Dartmouth Atlas of Health Care data, we modeled relationships between expenditures and patient and regional characteristics.

Participants and Setting

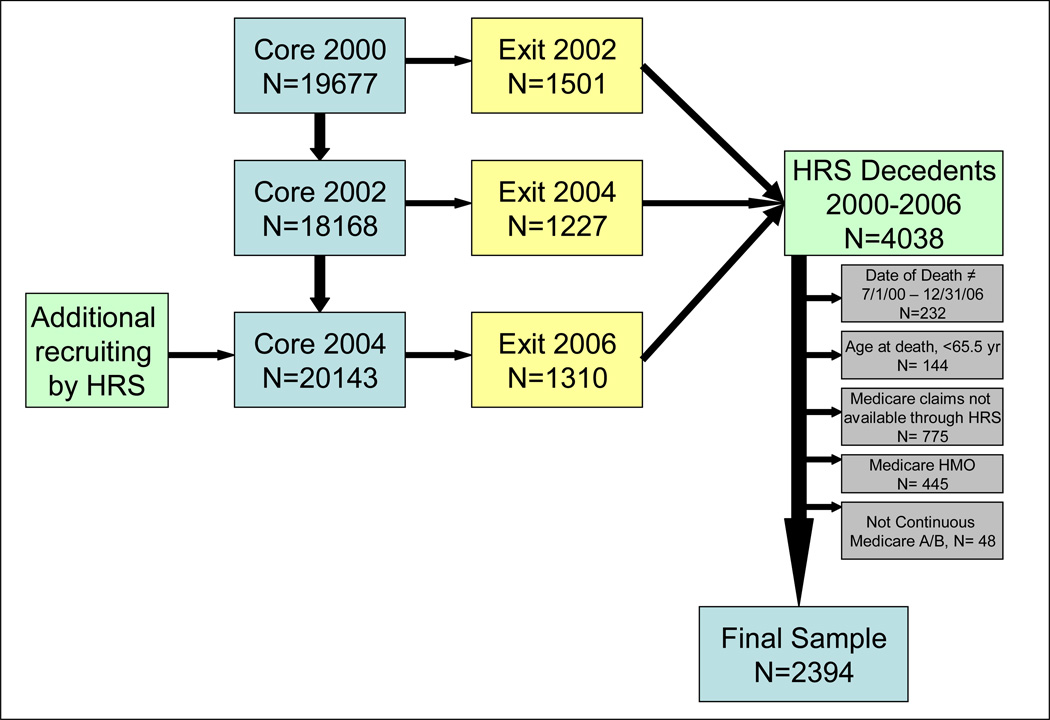

HRS decedents 65.5 years or older (n=2394), 2000–2006.

Measurement

Medicare expenditures in last 6 months of life were estimated in a series of 2-level multivariable regression models including 1) patient, 2) regional, and 3) patient and regional characteristics.

Results

Decline in function (rate ratio 1.64, 95%CI 1.46–1.83), Hispanic ethnicity (1.50, 1.22–1.85), African American race (1.43, 1.25–1.64), and certain chronic diseases including diabetes (1.16, 1.06–1.27), were associated with higher expenditures. Nearby family (0.90, 0.82–0.98) and dementia (0.78, 0.71–0.87) were associated with lower expenditures and advance care planning had no association. Regional characteristics, including end-of-life practice patterns (1.09, 1.06–1.14) and hospitals beds per capita (1.01, 1.00–1.02), were associated with higher expenditures. Patient characteristics explained 10% of overall variance and retained statistically significant relationships with expenditures after controlling for regional characteristics.

Limitations

Decedent sample, proxy informants, large proportion of variation remains unexplained.

Conclusions

Patient characteristics: functional decline, race/ethnicity, chronic disease, and nearby family, are important determinants of expenditures at end-of-life, independent of regional characteristics.

Introduction

Medical expenditures in the final months of life exceed costs of care during other years (1–3) and vary across demographic groups (2, 4–8) and geographic regions (9–11). Prior research suggests that high-cost, high-intensity treatment in the last year of life may not be associated with greater quality, improvements in outcomes, or increased satisfaction (10–15). Local medical resources (e.g., hospital bed supply, medical specialists per capita) influence treatment intensity (16–20) as do systemic factors specific to individual hospital-physician networks (21–23).

Studies of medical expenses at the end of life have typically focused on patients with a single diagnosis or characteristic and have not simultaneously considered regional variation (1, 5, 6, 24–26). Other studies using administrative datasets with limited information on individual patient characteristics have relied on census level proxies for sociodemographic characteristics (19) and have not examined contributions of other individual patient characteristics (e.g., functional status) (9). Identification of patient-level determinants of care intensity may reveal opportunities for patient-centered interventions to reduce medical costs and inappropriate variation. We hypothesized that race/ethnicity, financial net worth, social support and functional status are independently associated with treatment intensity after controlling for regional characteristics, and that these individual characteristics account for a substantial proportion of the previously described variation in end-of-life medical expenses. We sought to identify patient-level characteristics that predict Medicare expenditures, independent of geographic region and local medical resources, in the last 6 months of life among decedents from the Health and Retirement Study (HRS) (27). We also quantified the relative contributions of patient-level and regional characteristics to expenditures.

Methods

Conceptual Framework

The conceptual model for this study (28), detailed elsewhere, postulates that end-of-life treatment intensity is influenced by both regional and patient-based determinants. Regional determinants of treatment intensity include regional supply of medical resources, local or institutional patterns of care, and physician practice patterns. Patient-based determinants include factors such as medical need, financial access to care, personal treatment preferences, and communication of preferences, which are in turn influenced by specific quantifiable patient characteristics (demographic, socioeconomic, medical, functional, and psychosocial characteristics). Finally, family members frequently act as caregivers and surrogate decision makers, and thus may also affect end-of-life treatment intensity.

Data Sources

HRS data

We sampled decedents from HRS, a National Institute on Aging-funded, ongoing longitudinal and nationally-representative cohort of adults over the age of 50 years. The original HRS sample was assembled in 1992 and over 30,000 individuals have been enrolled. Complete description of HRS, including recruitment and enrollment procedures, is available at http://hrsonline.isr.umich.edu. Serial “Core” interviews are conducted every 2 years and response rates for each interview wave have exceeded 86%. During each interview cycle, HRS identifies participants who died since the last Core Interview and “Exit” interviews are conducted with proxies knowledgeable about the deceased participant (response rate=93%). Together, the Core and Exit Interviews include the participant’s demographic, economic, social and functional characteristics. HRS obtains dates of death from the National Death Index. Core interviews are completed a mean of 15.7 months (SD 12.6 mo.) before death and Exit interviews are completed a mean of 12.4 months (SD 3.9 mo.) post-death.

Medicare data

Over 80% of HRS participants provided authorization to merge their HRS data with Medicare claims (27). Medicare claims data are used to identify each subject’s chronic medical conditions and total expenditures during the last 6 months of life (29).

Regional data

Using the decedent’s zip code, we linked each subject to a hospital referral region (HRR) as defined by The Dartmouth Atlas of Healthcare (9). The Dartmouth Atlas database provides several measures of regional healthcare supply at the HRR level, including number of hospital beds, physicians, primary care physicians and specialist physicians (9). The Atlas has also calculated for each HRR an End of Life Expenditure Index (EOL-EI), a measure of physician practice patterns, based upon utilization patterns among Medicare beneficiaries in the last 6 months of life (10). Using the 2005 American Hospital Association (AHA) database, we calculated the proportion of hospitals designated as major teaching hospitals (i.e. members of the Association of American Medical College’s Council of Teaching Hospitals and Health Systems) and the proportion reporting palliative care services within each HRR.

Sample

We included HRS decedents aged 65.5 years or older, who died between July 1, 2000 and December 31, 2006. The decedents sampled during this 6 year span contributed data to the 2002, 2004 and 2006 Exit interview waves depending on the date of death. Data were then merged with data from each individual’s preceding Core interview in 2000, 2002, and 2004, respectively. To ensure complete claims data, we excluded those who were enrolled in Medicare managed care at any point during the last 6 months of life (n= 445) or were not continuously enrolled in Medicare Parts A and B (n= 48). Those excluded were not significantly different from the final study sample (n=2394) in terms of age, sex, race, education or net worth.

Outcome Variable

The primary outcome was total Medicare expenditures in the last 6 months of life. This measure includes all Medicare claims for inpatient, outpatient, skilled nursing facility, hospice and home care, as well as durable medical equipment. Claims that spanned the 180th day prior to death were prorated to estimate only that proportion of the expenditures within the last 6 months. We adjusted expenditures for inflation (2006 dollars) based on the medical services component of the consumer price index, and for geographic differences in Medicare price levels using the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) wage index.

Independent Variables

We selected patient-level and regional variables that could serve as empirical measures of each construct in the conceptual model. Patient-level variables collected from the Core interview included age, race and ethnicity, sex, education level, net worth, religiosity, urban residence, self-rated health and having relatives live nearby (a proxy for social support). Proxy-reported variables from the Exit interview included marital status, residential status (living in a nursing home, living alone, or living with others), non-Medicare insurance coverage (Medicaid, VA, MediGap), and completion of an advance directive or discussion of end-of-life care preferences. Functional status, based upon the subject’s need for assistance with 6 basic activities of daily living (ADL), was determined at the time of the Core interview and again by proxy report of status during the 3 months prior to death. Using both time points, we constructed categorical measures of functional stability or decline over time. Less than 1% of individuals experienced an improvement in functional status (transitioning from 1–3 ADL deficiencies to no deficiencies) and these subjects were combined with those who were independent at both time points. Chronic medical conditions were identified by the CMS Chronic Conditions ICD9 criteria (30), using Medicare claims from 6 to 18 months preceding death. This time frame was chosen to identify chronic conditions relevant to the subject’s ongoing medical care, while excluding new conditions identified in the last 6 months because of potential reverse causality with the expenditure outcome. We conducted sensitivity analyses of all final models to measure the impact on our findings of using different date cut points (0 to −12 months) as well as to test the effect of substituting self-reported chronic conditions for the claims-based designations (29); neither the magnitude of any of the effect sizes nor statistical significance changed. Regional variables drawn from the Dartmouth Atlas included: EOL-EI, number of hospital beds per 10,000 residents, and number of primary care and specialist physicians per 100,000 residents. As these latter two variables were highly collinear (0.80, p<0.01) they could not be included simultaneously in regression models. Regional variables drawn from AHA database included: the proportion of regional hospitals that are teaching hospitals and that have palliative care services.

Statistical Analysis

We evaluated summary statistics and frequency distributions for all variables. To investigate the relationships between patient-level and regional characteristics and the primary outcome, Medicare expenditures in the last 6 months of life, we estimated a series of 2-level models with a random intercept at the region (HRR) level. We compared 3 multivariable models and an unconditional model without covariates to evaluate relative contributions of each set of covariates toward the variation in the outcome (31). The first multivariable model included only patient characteristics and the random intercept for region. The second multivariable model included only regional characteristics. The final model included patient-level variables in the first level and regional variables in the second level to account for clustering of patients within regions. The proportion of variance explained by each model was calculated as the total variance from the unconditional model minus the total variance from the conditional model, divided by total variance from the unconditional model (31).

Due to the skewed distribution of the outcome, we used a gamma distribution with a log link for the regression models. Gamma coefficients generated by the regression models were exponentiated to retransform them into rate ratio estimates.

We explored the possibility that functional status could mediate the relationship between chronic conditions and expenditures by comparing the final model to one without functional status variables. To examine whether our findings are consistent among those with supplemental insurance, we also reconstructed the models among the subgroup with supplemental Medigap insurance. We used multiple imputations (cycles=5) to account for missing data (32). Missing data accounted for 3.5% of data values and were most frequent among race (2%), education (7%), and net worth (14%). We used SAS 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina) for all statistical analyses. The study was approved by the Mount Sinai School of Medicine IRB, the HRS Data Confidentiality Committee, and the CMS Privacy Board.

Role of the Funding Source

Dr. Kelley is a Brookdale Leadership in Aging Fellow and Dr. Sarkisian is her mentor on this award. Dr. Morrison is the recipient of a Mid-Career Investigator Award in Patient-Oriented Research (K24 AG022345) from the National Institute on Aging and supported by the National Palliative Care Research Center. Drs. Sarkisian and Morrison are supported by the VA. No sponsors or funders had any role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; or preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Results

Table 1 presents patient characteristics. Median total Medicare expenditures in the last 6 months of life, adjusted to 2006 U.S. dollars, were $22,407 (range= $0 – $391,773; interquartiles $9,087and $40,802, respectively).

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics (n=2394) and Regional Characteristics

| Participant Characteristics | |

| Age, mean (SD), years | 83.4 (8.3) |

| Female, n (%*) | 1305 (55) |

| Race | |

| Non-Hispanic White, n (%) | 1890 (79) |

| African American, n (%) | 303 (13) |

| Hispanic, n (%) | 121 (5) |

| Other, n (%) | 28 (1) |

| Education | |

| Less than 12 years, n (%) | 1112 (46) |

| 12 years or more, n (%) | 1260 (53) |

| Marital Status | |

| Married, n (%) | 920 (38) |

| Never Married, n (%) | 86 (4) |

| Widowed, n (%) | 1155 (48) |

| Separated or Divorced, n (%) | 208 (9) |

| Net Worth in US dollars, median | 91,000 |

| Residential Status | |

| Nursing Home, n (%) | 970 (41) |

| Live Alone, n (%) | 958 (40) |

| Live with Others, n (%) | 444 (19) |

| Relative Live Nearby, n (%) | 789 (33) |

| Religiosity | |

| Religion is very important, n (%) | 1465 (61) |

| Religion is somewhat to not important, n (%) | 907 (38) |

| Functional Status† | |

| Stable, Independent in ADLs, n (%) | 472 (20) |

| Stable, Moderate (1–3 ADL) impairments, n (%) | 119 (5) |

| Stable, Severe (4–6 ADL) impairments, n (%) | 425 (18) |

| Declined, Independent to Moderate, n (%) | 216 (9) |

| Declined, Moderate to Severe, n (%) | 331 (14) |

| Declined, Independent to Severe, n (%) | 712 (30) |

| Additional insurance coverage | |

| Medicaid, n (%) | 571 (24) |

| VA , n (%) | 132 (6) |

| MediGap (private), n (%) | 1439 (60) |

| Advance Directive completed, n (%) | 1472 (61) |

| Discussion of end of life care preferences, n (%) | 1301 (54) |

| Self-rated Health, fair/poor, n (%) | 1403 (63) |

| Chronic Medical Conditions | |

| Ischemic Heart Disease, n (%) | 1049 (44) |

| Congestive Heart Failure, n (%) | 917 (38) |

| Atrial Fibrillation, n (%) | 558 (23) |

| Alzheimers/Dementia, n (%) | 620 (26) |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 754 (32) |

| Chronic Kidney Disease, n (%) | 437 (18) |

| Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease, n (%) | 759 (32) |

| Depression, n (%) | 364 (15) |

| Cancer, n (%) | 372 (15) |

| Arthritis (Osteoarthritis / Rheumatoid Arthritis), n (%) | 647 (27) |

| Stroke or Transient Ischemic Attack, n (%) | 458 (19) |

| 4 or more Chronic Medical Conditions, n (%) | 953(39.8) |

| Urban Residence | 922 (38.5) |

| Regional Characteristics‡ | |

| Hospital Beds per 10,000 residents, mean (SD) | 25 (5) |

| Specialists per 100,000 residents, mean (SD) | 124 (23) |

| Proportion of Regional Hospitals that are Teaching Hospitals, mean (range) | 0.07 (0–0.62) |

| Proportion of Regional Hospitals Reporting Palliative Care services, mean (range) | 0.38 (0.19–1.0) |

Percentage may not add to 100 due to rounding error.

Functional stability or decline over time measured by comparing functional status at last Core interview to proxy report of status during the 3 months prior to death.

Regional data included for every subject, therefore weighted by the number of subjects in each region.

Table 2 reports rate ratio estimates for the multivariable regression models: 1) patient characteristics, 2) regional characteristics, and 3) patient and regional characteristics. For example, in Model 1, holding all other characteristics equal, a person living in an urban area incurs 12% more Medicare expenditures compared to someone not in an urban area (rate ratio= 1.12, 95% CI 1.02–1.24).

Table 2.

Patient and Regional Determinants of Total Medicare Expenditures in Last 6 Months

| Model 1: Patient Determinants |

Model 2: Regional Determinants |

Model 3: Patient and Regional Determinants |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proportion of Variance Explained by Model | 0.10 | 0.05 | 0.15 | |||

| Rate Ratio |

95% CI | Rate Ratio |

95% CI | Rate Ratio |

95% CI | |

| Patient Characteristics | ||||||

| Age, in years | 0.98 | 0.97–0.99 | 0.98 | 0.97–0.98 | ||

| Female | 0.97 | 0.89–1.07 | 0.96 | 0.87–1.05 | ||

| Race (reference=non-Hispanic White) | ||||||

| African American | 1.43 | 1.25–1.64 | 1.37 | 1.20–1.58 | ||

| Hispanic | 1.50 | 1.22–1.85 | 1.44 | 1.17–1.77 | ||

| Other | 1.16 | 0.80–1.68 | 1.20 | 0.83–1.73 | ||

| Education (reference=education <12 years) | ||||||

| 12 years or more | 0.91 | 0.83–1.00 | 0.93 | 0.85–1.02 | ||

| Marital Status (reference= married) | ||||||

| Never Married | 0.83 | 0.67–1.04 | 0.84 | 0.67–1.04 | ||

| Widowed | 0.96 | 0.87–1.07 | 0.98 | 0.88–1.08 | ||

| Separated or Divorced | 0.88 | 0.75–1.04 | 0.91 | 0.77–1.06 | ||

| Net Worth (reference= lowest quartile) | ||||||

| 4th (highest) quartile | 0.93 | 0.79–1.09 | 0.93 | 0.79–1.08 | ||

| 3rd quartile | 0.96 | 0.84–1.10 | 0.96 | 0.84–1.10 | ||

| 2nd quartile | 1.02 | 0.89–1.17 | 1.03 | 0.90–1.17 | ||

| Residential Status (reference=live with others) | ||||||

| Nursing Home | 1.08 | 0.97–1.21 | 1.10 | 0.98–1.23 | ||

| Live Alone | 1.02 | 0.92–1.14 | 1.01 | 0.90–1.12 | ||

| Relative Live Nearby | 0.90 | 0.82–0.98 | 0.90 | 0.82–0.98 | ||

| Religion is very important | 1.02 | 0.94–1.12 | 1.02 | 0.94–1.11 | ||

| Functional Status† (reference= no impairments) | ||||||

| Stable, Moderate (1–3 ADL)* impairments | 1.09 | 0.89–1.33 | 1.12 | 0.92–1.36 | ||

| Stable, Severe (4–6 ADL)* impairments | 1.21 | 1.04–1.40 | 1.20 | 1.04–1.39 | ||

| Declined, Independent to Moderate | 1.31 | 1.12–1.53 | 1.34 | 1.15–1.56 | ||

| Declined, Moderate to Severe | 1.42 | 1.23–1.65 | 1.42 | 1.23–1.64 | ||

| Declined, Independent to Severe | 1.64 | 1.46–1.83 | 1.64 | 1.46–1.84 | ||

| Medicaid | 0.96 | 0.86–1.08 | 0.94 | 0.84–1.06 | ||

| VA | 0.89 | 0.74–1.07 | 0.88 | 0.74–1.06 | ||

| MediGap (private) | 1.15 | 1.04–1.27 | 1.14 | 1.03–1.26 | ||

| Advance Directive completed | 1.02 | 0.93–1.13 | 1.04 | 0.94–1.14 | ||

| Discussion of end of life care preferences | 0.95 | 0.87–1.03 | 0.95 | 0.88–1.04 | ||

| Self-rated Health, fair/poor | 0.99 | 0.91–1.09 | 1.00 | 0.91–1.10 | ||

| Ischemic Heart Disease/Myocardial Infarction | 1.05 | 0.96–1.15 | 1.04 | 0.95–1.14 | ||

| Congestive Heart Failure | 1.07 | 0.97–1.14 | 1.08 | 0.98–1.18 | ||

| Atrial Fibrillation | 1.03 | 0.94–1.14 | 1.04 | 0.94–1.15 | ||

| Alzheimers/Dementia | 0.78 | 0.71–0.87 | 0.78 | 0.70–0.86 | ||

| Diabetes | 1.16 | 1.06–1.27 | 1.14 | 1.04–1.24 | ||

| Chronic Kidney Disease | 1.22 | 1.10–1.36 | 1.24 | 1.11–1.38 | ||

| COPD‡ | 1.04 | 0.95–1.14 | 1.03 | 0.95–1.13 | ||

| Depression | 1.02 | 0.91–1.14 | 1.03 | 0.92–1.15 | ||

| Arthritis (OA/RA)§ | 1.23 | 1.12–1.35 | 1.23 | 1.12–1.35 | ||

| Stroke or TIA∥ | 1.17 | 1.05–1.30 | 1.15 | 1.04–1.28 | ||

| Cancer | 1.07 | 0.95–1.20 | 1.06 | 0.95–1.19 | ||

| Urban Residence | 1.12 | 1.02–1.24 | 1.03 | 0.92–1.14 | ||

| Regional Characteristics | ||||||

| Hospital Beds per 10,000 residents | 1.01 | 1.00–1.02 | 1.01 | 1.00–1.02 | ||

| Specialists per 100,000 residents | 1.00 | 1.00–1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00–1.00 | ||

| Proportion of Regional Hospitals that are Teaching Hospitals | 1.00 | 0.99–1.01 | 1.00 | 0.99–1.01 | ||

| Proportion of Regional Hospitals with Palliative Care services | 1.00 | 1.00–1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00–1.00 | ||

| End of Life Expenditure Index (EOL-EI) | 1.10 | 1.06–1.14 | 1.09 | 1.05–1.13 | ||

Activities of Daily Living

Functional stability or decline over time measured by comparing functional status at last Core interview to proxy report of status during the 3 months prior to death.

Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

Osteoarthritis/Rheumatoid Arthritis

Transient Ischemic Attack

Model 1 (Column 1 of Table 2) evaluates the association between patient-level characteristics and Medicare expenditures. African American race and Hispanic ethnicity are strongly correlated with increased expenditures (1.43, 1.25–1.64 and 1.50, 1.22–1.85, respectively). Having stable but severe functional impairment or experiencing a decline in functional status are also associated with increased expenditure (1.21–1.64, all p<=0.01). Private insurance coverage through a MediGap policy is associated with higher Medicare expenditures (1.15, 1.04–1.27). Having relatives live nearby is associated with decreased expenditures (0.90, 0.82–0.98). Several chronic medical conditions are associated with higher expenditures, including diabetes (1.16, 1.06–1.27), chronic kidney disease (1.22, 1.10–1.36), arthritis (1.23, 1.12–1.35) and stroke/transient ischemic attack (1.17, 1.05–1.30). Additionally, having 4 or more chronic conditions is associated with higher expenditures (1.29, 1.19–1.40) in models leaving out individual conditions (data not shown). Dementia (including Alzheimer’s disease), however, is correlated with a reduction in overall expenditures (0.78, 0.71–0.87). When functional characteristics were removed from the model, relationships between cancer and heart failure and higher expenditures became evident but did not reach statistical significance (data not shown). Advance care planning (i.e., written advance directives or any discussion of end-of-life treatment preferences) was not associated with expenditures, nor was sex, marital status, education, net worth, nursing home residence or religiosity. Person-level characteristics included in Model 1 account for 10% of the expenditure variation in the last 6 months of life.

Model 2 (Column 2 of Table 2) evaluates the association between regional characteristics and resources on Medicare expenditures. The EOL-EI, defined as quintiles of regional practice patterns for end of life treatment intensity (10), is strongly associated with Medicare expenditures (1.10, 1.06–1.14). For example, a person in a region with EOL-EI=2 incurs 9% more Medicare expenditures in the last 6 months of life than a person in a region with EOL-EI=1, holding all other characteristics equal. An increasing number of hospital beds per capita is associated with higher expenditures at the end of life (1.01, 1.00–1.02). For example, each additional bed per 10,000 residents would increase Medicare expenditures in the last 6 months of life by 1%, all other factors held equal. The regional characteristics included in Model 2 account for 5% of the total variation in Medicare expenditures in the last 6 months of life.

Model 3 (Column 3 of Table 2) evaluates the simultaneous association between patient-level and regional characteristics and Medicare expenditures in a 2-level multivariable model. All patient characteristics associated with expenditures in Model 1 maintain their associations and effect sizes after the addition of regional level characteristics. Similarly, EOL-EI and number of hospital beds, the regional variables found to be associated with greater expenditures in Model 2, maintained a similar effect size after adjusting for patient characteristics. The independent variables in model 3 explain 15% of the variation in end-of-life expenditures.

When we reconstructed all 3 models using only those having Medigap insurance (n=1439), we found similar patterns of associations, with patient characteristics explaining 6% of the variation, regional characteristics 4%, and the full two-level model 10% (data not shown).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this study is the first to combine detailed longitudinal patient-level data, individual Medicare claims, and regional characteristics to examine regional and patient-level correlates of expenditures simultaneously. Our analyses demonstrate that a substantial portion of previously described variations in healthcare expenditures are due to patient-level characteristics, and those factors remain highly significant after accounting for regional characteristics. These results are consistent with recent work examining sources of geographic variation in Medicare spending (33) and extend those analyses by examining more detailed health, functional, and social characteristics. The association between regional characteristics and expenditures also remains significant when adjusting for patient-level characteristics. Notably, a large proportion of observed variation remains unexplained after controlling for both patient and regional characteristics.

Functional impairment and decline are powerful, independent predictors of Medicare expenditures at the end of life. Prior work has demonstrated the high morbidity and mortality associated with functional impairment, particularly among hospitalized older adults (34–37), and the general lack of disease-specific patterns of functional decline (38). This study provides additional evidence linking functional impairment and total Medicare expenditures. Exploratory analyses suggest that for some conditions, including cancer and heart failure, functional status may partially mediate the relationship with expenditures. Quality and coordination of care for patients with functional impairment and multiple chronic medical conditions are often poor (39–42). Based upon these analyses we hypothesize that healthcare reforms may have greater impact on improving care and reducing costs if they prioritize patient-centered, rather than single disease-oriented, models of care. These efforts should include high-quality primary care and well coordinated care for these complicated and functionally impaired patients.

The substantial association between having a nearby relative and lower Medicare costs is noteworthy and may indicate that relatives can act as caregivers or advocates to help patients avoid undesired hospitalizations and interventions. The availability of a caregiver may allow patients to choose a preferred treatment plan (e.g., care at home instead of in the hospital) that incurs fewer Medicare expenses. However, such a treatment plan may lead to shifting of expenses from Medicare to the patient or caregiver in the form of lost time from work or paying for hired caregivers. Further investigation of this finding is warranted given the potential for important policy implications.

We observed significantly greater expenditures among African Americans and Hispanics than non-Hispanic Whites. This finding is consistent with other studies (6, 25); further research is needed to determine the extent to which this greater level of treatment intensity is due to patient preferences, differential access to medical services, disparities in preventative care and provider continuity, or other unknown factors (8, 47–49). Notably, we found no association between Medicare expenditures and advance directives or discussion of end-of-life care preferences. These data do not provide sufficient detail to evaluate the possibility that some patients expressed a care preference for intensive treatment - one possible explanation for this finding. However, for the subset of patients with a living will (n=1042), 92% stated a preference for comfort focused care. These data suggest that patient preferences as documented in living wills are poorly correlated with treatment delivered – consistent with other published data (16, 43–45). Additionally, based on prior work (46) we expected religiosity to be correlated with increased expenditures, yet we found no association.

This study has limitations. Our analyses examined only decedents and did not account for survivors of intensive medical care. However, we intend this study to build upon the substantial body of prior work that has focused on decedents (11, 23). Future research is needed to prospectively apply this conceptual framework to the full spectrum of adults with serious and life-threatening illness. Additionally, several pieces of data were collected retrospectively from proxy informants and subject to recall bias. We identified chronic conditions through claims rather than by patient report, which may identify only those with very severe disease and overestimate the relationship with expenditures, as we hypothesize was the case with arthritis. Using claims to identify chronic conditions may also minimize regional effects due to varying diagnostic practices (50). Our data also contained a limited set of predictors and do not contain adequate proxy measures of physician practice patterns, specific patient preferences for end-of-life care, or family preferences regarding care. We were also not able to control for the availability of palliative care community services, including hospice within regions. Finally, in order to ensure comparability across respondents with differing supplementary insurance and to facilitate comparisons with other studies, these analyses only consider Medicare expenditures and include neither costs covered by other insurance sources (e.g., Medicaid, VA) nor out-of-pocket expenditures.

In conclusion, patient-level characteristics - including functional decline, chronic disease, caregiver support, race and ethnicity- are significant determinants of Medicare expenditures at the end of life, independent of regional characteristics. While regional variation must be addressed, our findings suggest that a larger proportion of overall variation is driven by differences among individuals and the majority of the observed variation remains unexplained. Furthermore, this study indicates that specific characteristics place individuals at a greater “risk” of high-cost, high-intensity treatment: functional decline, chronic medical conditions and not having family nearby. This suggests opportunities for interventions that identify and target these patients at increased risk for high-intensity treatment in order to determine when and if high-cost life-sustaining treatment is consistent with patient preferences or indicative of inappropriate, poor quality medical care. This knowledge will be critical for the development of policies and guidelines to decrease population-level health disparities, excessive expenditures, and patient suffering.

Figure 1. Flow Chart of HRS decedent sample.

The sampling frame encompassed deaths over a 6 year period and includes data spanning 6 years of HRS interviews. For each subject, data from a single Core and single Exit interview were used: Core 2000+Exit 2002, Core 2002+Exit 2004, Core 2004+Exit 2006.

Acknowledgments

Financial Support:

The Brookale Foundation provided support for this study. Dr. Kelley is a Brookdale Leadership in Aging Fellow. Dr. Morrison is the recipient of a Mid-Career Investigator Award in Patient-Oriented Research (K24 AG022345) from the National Institute on Aging and supported by the National Palliative Care Research Center. Dr. Sarkisian is supported by the VA Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System Geriatric Research Education Clinical Center. No sponsors or funders had any role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; or preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Reproducible Research Statement

Study protocol: available to interested readers by contacting Dr. Kelley at amy.kelley@mssm.edu. Statistical code and data: not available.

Data: available through the Health and Retirement Study (http://hrsonline.isr.umich.edu), ResDAC (http://www.resdac.umn.edu/Medicare/requesting_data_NewUse.asp), and the Dartmouth Atlas of Health Care(http://www.dartmouthatlas.org/).

References

- 1.Hoover DR, Crystal S, Kumar R, Sambamoorthi U, Cantor JC. Medical expenditures during the last year of life: findings from the 1992–1996 Medicare current beneficiary survey. Health Serv Res. 2002;37(6):1625–1642. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.01113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hogan C, Lunney J, Gabel J, Lynn J. Medicare beneficiaries' costs of care in the last year of life. Health Aff (Millwood) 2001;20(4):188–195. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.20.4.188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lubitz JD, Riley GF. Trends in Medicare payments in the last year of life. N Engl J Med. 1993;328(15):1092–1096. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199304153281506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shugarman LR, Campbell DE, Bird CE, Gabel J, A Louis T, Lynn J. Differences in Medicare expenditures during the last 3 years of life. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19(2):127–135. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.30223.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bird CE, Shugarman LR, Lynn J. Age and gender differences in health care utilization and spending for medicare beneficiaries in their last years of life. J Palliat Med. 2002;5(5):705–712. doi: 10.1089/109662102320880525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barnato AE, Chang CC, Saynina O, Garber AM. Influence of race on inpatient treatment intensity at the end of life. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(3):338–345. doi: 10.1007/s11606-006-0088-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Levinsky NG, Yu W, Ash A, Moskowitz M, Gazelle G, Saynina O, et al. Influence of age on Medicare expenditures and medical care in the last year of life. JAMA. 2001;286(11):1349–1355. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.11.1349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Welch LC, Teno JM, Mor V. End-of-life care in black and white: race matters for medical care of dying patients and their families. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(7):1145–1153. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53357.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wennberg JE, Cooper M. The Dartmouth Atlas of Health Care. 2009 Jul 20; [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fisher ES, Wennberg DE, Stukel TA, Gottlieb DJ, Lucas FL, Pinder EL. The implications of regional variations in Medicare spending. Part 1: the content, quality, and accessibility of care. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138(4):273–287. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-138-4-200302180-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fisher ES, Wennberg DE, Stukel TA, Gottlieb DJ, Lucas FL, Pinder EL. The implications of regional variations in Medicare spending. Part 2: health outcomes and satisfaction with care. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138(4):288–298. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-138-4-200302180-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wennberg JE, Bronner K, Skinner JS, Fisher ES, Goodman DC. Inpatient care intensity and patients' ratings of their hospital experiences. Health Aff (Millwood) 2009;28(1):103–112. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.1.103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Skinner J, Chandra A, Goodman D, Fisher ES. The elusive connection between health care spending and quality. Health Aff (Millwood) 2009;28(1):w119–w123. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.1.w119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yasaitis L, Fisher ES, Skinner JS, Chandra A. Hospital quality and intensity of spending: is there an association? Health Aff (Millwood) 2009;28(4):w566–w572. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.4.w566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baicker K, Chandra A. Medicare spending, the physician workforce, and beneficiaries' quality of care, Health Aff (Millwood) 2004:W184–w197. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.w4.184. Suppl Web Exclusives. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pritchard RS, Fisher ES, Teno JM, Sharp SM, Reding DJ, Knaus WA, et al. Influence of patient preferences and local health system characteristics on the place of death. SUPPORT Investigators. Study to Understand Prognoses and Preferences for Risks and Outcomes of Treatment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1998;46(10):1242–1250. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1998.tb04540.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Virnig BA, Kind S, McBean M, Fisher E. Geographic variation in hospice use prior to death. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48(9):1117–1125. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb04789.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fisher ES, Wennberg JE. Health care quality, geographic variations, and the challenge of supply-sensitive care. Perspect Biol Med. 2003;46(1):69–79. doi: 10.1353/pbm.2003.0004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fisher ES, Wennberg JE, Stukel TA, Skinner JS, Sharp SM, Freeman JL, et al. Associations among hospital capacity, utilization, and mortality of US Medicare beneficiaries, controlling for sociodemographic factors. Health Serv Res. 2000;34(6):1351–1362. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Earle CC, Neville BA, Landrum MB, Ayanian JZ, Block SD, Weeks JC. Trends in the aggressiveness of cancer care near the end of life. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(2):315–321. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.08.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shortell SM, Casalino LP. Health care reform requires accountable care systems. JAMA. 2008;300(1):95. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.1.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cortese D, Smoldt R. Taking Steps Toward Integration. Health Aff. 2007;26(1):w68. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.26.1.w68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Skinner J, Staiger D, Fisher ES. Looking back, moving forward. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(7):569–574. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1000448. discussion 574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Emanuel EJ, Young-Xu Y, Levinsky NG, Gazelle G, Saynina O, Ash AS. Chemotherapy use among Medicare beneficiaries at the end of life. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138(8):639–643. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-138-8-200304150-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hanchate A, Kronman AC, Young-Xu Y, Ash AS, Emanuel E. Racial and ethnic differences in end-of-life costs: why do minorities cost more than whites? Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(5):493–501. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2008.616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shugarman LR, Bird CE, Schuster CR, Lynn J. Age and gender differences in Medicare expenditures at the end of life for colorectal cancer decedents. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2007;16(2):214–227. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2006.0012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Health and Retirement Study. Jul 20; [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kelley AS, Morrison RS, Wenger NS, Ettner SL, Sarkisian CA. Determinants of Treatment Intensity for Patients with Serious Illness: A New Conceptual Framework. Journal of Palliative Medicine. 2010;13(7):807–813. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2010.0007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bhandari A, Wagner T. Self-reported utilization of health care services: improving measurement and accuracy. Med Care Res Rev. 2006;63(2):217–235. doi: 10.1177/1077558705285298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chronic Condition Data Warehouse User Manual, Version 1.5. Buccaneer Computer Systems & Services, Inc.; 2009. May, [Google Scholar]

- 31.Raudenbush SW, Bryk AS. Hierarchical Linear Models: Applications and Data Analysis Methods. 2nd ed. Sage Publications; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schafer JL. Multiple Imputation: a primer. Stat Methods Med Res. 1999;8(1):3–15. doi: 10.1177/096228029900800102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zuckerman S, Waidmann T, Berenson R, Hadley J. Clarifying sources of geographic differences in Medicare spending. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(1):54–62. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0909253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Boyd CM, Xue QL, Simpson CF, Guralnik JM, Fried LP. Frailty, hospitalization, and progression of disability in a cohort of disabled older women. Am J Med. 2005;118(11):1225–1231. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.01.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gill TM, Allore HG, Holford TR, Guo Z. Hospitalization, restricted activity, and the development of disability among older persons. JAMA. 2004;292(17):2115–2124. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.17.2115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Covinsky KE, Palmer RM, Fortinsky RH, Counsell SR, Stewart AL, Kresevic D, et al. Loss of independence in activities of daily living in older adults hospitalized with medical illnesses: increased vulnerability with age. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51(4):451–458. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51152.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Reuben DB, Rubenstein LV, Hirsch SH, Hays RD. Value of functional status as a predictor of mortality: results of a prospective study. Am J Med. 1992;93(6):663–669. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(92)90200-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gill TM, Gahbauer EA, Han L, Allore HG. Trajectories of disability in the last year of life. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(13):1173–1180. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0909087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Boyd CM, Darer J, Boult C, Fried LP, Boult L, Wu AW. Clinical practice guidelines and quality of care for older patients with multiple comorbid diseases: implications for pay for performance. JAMA. 2005;294(6):716–724. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.6.716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fried LP, Ferrucci L, Darer J, Williamson JD, Anderson G. Untangling the concepts of disability, frailty, and comorbidity: implications for improved targeting and care. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2004;59(3):255–263. doi: 10.1093/gerona/59.3.m255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wolff JL, Starfield B, Anderson G. Prevalence, expenditures, and complications of multiple chronic conditions in the elderly. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162(20):2269–2276. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.20.2269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Werner RM, Greenfield S, Fung C, Turner BJ. Measuring quality of care in patients with multiple clinical conditions: summary of a conference conducted by the Society of General Internal Medicine. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(8):1206–1211. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0230-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wenger NS, Phillips RS, Teno JM, Oye RK, Dawson NV, Liu H, et al. Physician understanding of patient resuscitation preferences: insights and clinical implications. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48(5 Suppl):S44–S51. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb03140.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Teno JM, Fisher ES, Hamel MB, Coppola K, Dawson NV. Medical care inconsistent with patients' treatment goals: association with 1-year Medicare resource use and survival. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50(3):496–500. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50116.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Teno JM, Gruneir A, Schwartz Z, Nanda A, Wetle T. Association between advance directives and quality of end-of-life care: a national study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55(2):189–194. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01045.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Phelps AC, Maciejewski PK, Nilsson M, Balboni TA, Wright AA, Paulk ME, et al. Religious Coping and Use of Intensive Life-Prolonging Care Near Death in Patients With Advanced Cancer. JAMA. 2009;301(11):1140. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Barnato AE, Herndon MB, Anthony DL, Gallagher PM, Skinner JS, Bynum JP, et al. Are regional variations in end-of-life care intensity explained by patient preferences?: A Study of the US Medicare Population. Med Care. 2007;45(5):386–393. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000255248.79308.41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Virnig BA, Morgan RO, Persily NA, DeVito CA. Racial and income differences in use of the hospice benefit between the medicare managed care and medicare fee-for-service. J Palliat Med. 1999;2(1):23–31. doi: 10.1089/jpm.1999.2.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kelley AS, Wenger N, Sarkisian CA. End of Life Preferences and Planning Among Older Latinos. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 58(6):1109–1116. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.02853.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Song Y, Skinner J, Bynum J, Sutherland J, Wennberg JE, Fisher ES. Regional variations in diagnostic practices. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(1):45. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0910881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]