Abstract

Purpose

IncreasedsHER2 is an indicator of poor prognosisin HER2+ metastatic breast cancer. This study evaluated the levels of sHER2 during treatment and at time of recurrence in the adjuvant N9831 clinical trial.

Patients and Methods

Aims were to describe sHER2 levels during treatment and at time of recurrence in patients randomized to Arms A (standard chemotherapy), B (standard chemotherapy with sequential trastuzumab) and C (standard chemotherapy with concurrent trastuzumab). Baseline samples were available for 2318 patients. Serial samples were available from 105 patients and recurrence samples were available from 124 patients. Cutoff for this assay was 15ng/mL. Statistical methods included repeated measures linear models, Wilcoxon rank sum tests, and Cox regression models

Results

Differences between groups existed by age, menopausal status and hormone receptor status. Within Arms A, B and C, patients with baseline sHER2 ≥ 15ng/mL were found to have worse DFS than patients with baseline sHER2 <15ng/mL (A: HR=1.81, p=0.0014; B: HR=2.08, p=0.0015; C: HR=1.96, p =0.01). Among the 124 patients with disease recurrence, sHER2 levels increased from baseline to time of recurrence in Arm A and Arm B while it remained unchanged in Arm C. Patients with recurrence sHER2 levels ≥ 15ng/mL had shorter survival time following recurrence with 3-year OS of 51% compared to 77% for the <15ng/mL sHER2 group (HR=2.36; 95% CI: 1.19–4.70, p=0.01).

Conclusions

In early stage HER2-positive breast cancer, high baseline sHER2 level is a prognostic marker associated with shorter DFS and high sHER2 level at recurrence is predictive of shorter survival.

INTRODUCTION

Breast carcinoma is a significant health problem worldwide, with an estimated 1.38 million women diagnosed annually.1 There remains a significant interest and need to identify prognostic and predictive characteristics of the disease to help understand natural history and impact therapeutic selection.2 The discovery of amplification and/or overexpression of the tyrosine kinase human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) in 15–20% of invasive breast cancers, and the correlation of HER2 overexpression with worse prognosis in both locoregional and advanced disease, has revolutionized the understanding of prognosis and therapeutic management of breast cancer patients.3

Clinical advancements have principally been accomplished with the use of trastuzumab, a fully humanized monoclonal antibody against HER2 that has been shown to have activity against HER2 overexpressing invasive breast cancers in both locoregional and advanced disease.4–7 Identifying biological predictors to optimize prognosis, and selecting patients for anti-HER2 therapy with or without other therapies, are significant foci of our research and that of others.

In addition to evaluating HER2 and other molecular markers in tissue specimens, there has been great interest in serologic-based testing for circulating HER2 due to the accessibility of serologic testing and the possibility of serial monitoring for tumor response to therapy.8 HER2 is a 185 kDa protein composed of an intracellular domain, a transmembrane, and an extracellular domain (ECD). The ECD is occasionally cleaved by matrix metalloproteinases and released into the peripheral circulation as soluble HER2 (sHER2),9 where it can be quantified using commercially available enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs).10 Therefore, sHER2 is a logical marker to evaluate as a prognostic and/or predictive factor in the setting of metastatic and early stage HER2 overexpressing breast cancer.

Some data gathered over the last few years support the evaluation of this marker while others do not. 11–14 Carney, et al, conducted a meta-analysis of 55 publications (n >6500 patients) evaluating the prevalence, prognosis, prediction of response to therapy, and potential use of sHER2 for monitoring breast cancer.15 From 0% to 38% (mean 18.5%) of patients with HER2-positive early stage and from 23% to 80% (mean 43%) of patients with metastatic breast cancer (MBC) had sHER2 concentrations that were above the control cutoff described in each publication. The study suggested that high circulating sHER2 levels are a prognostic factor of inferior progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS), and a predictive factor of poor response to endocrine therapy and some chemotherapy regimens. Also noted was that serial increases of sHER2 might precede the appearance of metastases and longitudinal sHER2 changes could predict the clinical course of the underlying disease. Although the data regarding MBC demonstrate a possible correlation of tumor burden and clinical outcome with sHER2, there are very little data regarding the significance of sHER2 levels in the adjuvant setting. Our North Central Cancer Treatment Group (NCCTG) adjuvant trial N9831 is an ideal study to explore the role of sHER2 as a potential prognostic or predictive marker, as it is a large prospective study of chemotherapy alone or with trastuzumab for patients with HER2-positive resected breast cancer.16

METHODS

The eligibility criteria and study design for N9831 have been previously reported.4 Patients were required to have histologically confirmed adenocarcinoma of the breast, with 3+ immunohistochemical staining for HER2 or amplification of the HER2 gene by fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH ≥2.0 ratio), with either node-positive or high-risk node-negative disease to be eligible for the study. The N9831 trial had 3 treatments arms (Arm A: doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide every 3 weeks x 4 cycles followed by weekly paclitaxel x 12; Arm B/sequential trastuzumab treatment: doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide every 3 weeks x 4 cycles followed by weekly paclitaxel x 12, followed by 52 weeks of weekly trastuzumab; Arm C/concurrent trastuzumab treatment: doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide every 3 weeks x 4 cycles followed by weekly paclitaxel plus concurrent trastuzumab x 12, followed by 40 more weeks of weekly trastuzumab).

With a plan to examine correlations with clinical outcomes, serum samples were scheduled to be obtained at baseline in all patients (study entry; all patients were post primary surgical resection of tumors), throughout treatment in a subset of 35 patients per arm (every 3 months for the first year then every 6 months from year 2 to year 5 – these samples were part of a planned cardiac marker substudy), and when available, at time of tumor recurrence for all patients with recurrent disease. Median follow-up for these patients was 4.7 years. Specimens were analyzed using the commercially available Advia Centaur serum HER2 assay (Wilex/Oncogene Science, Cambridge, MA). Payne, et al, demonstrated that trastuzumab does not interfere with this serum HER2 assay.17

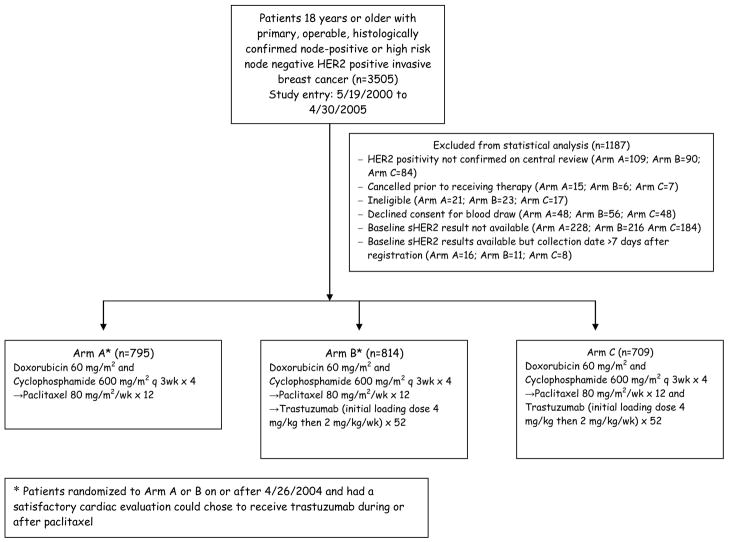

The cutoff for this assay for normal and high levels was 15 ng/mL per FDA-approved ADVIA Centaur® HER-2/neu assay recommendation. Out of the total 3505 patients enrolled in the trial, baseline samples were available for 2318 patients participating in Arms A (795), B (814) and C (709). 1187 patients were excluded from the statistical analysis for various reasons as outlined in Figure 1. Serial samples were available from 105 patients and recurrence samples were available from 124 patients for analyses. Statistical methods included Wilcoxon rank sum tests and Cox regression models. A linear mixed effects model was utilized in the analysis of serial sHER2 levels. DFS and OS analyses were stratified by ER/PR and nodal status. Multivariate analyses stratified by ER/PR and nodal status were conducted including additional patient characteristics that were significant or borderline significant predictors of baseline sHER2 ≥15 ng/ml. These included menopausal status, age, tumor size, tumor grade and race. Age was not included simultaneously with menopausal status in models due to their high correlation.

Figure 1.

NCCTG N9831 sHER2 Analysis. HER2; human epidermal growth factor receptor 2.

RESULTS

Baseline characteristics between patients with sHER2 <15 ng/mL (n=2,029) and patients with sHER2 ≥15 ng/mL (n=289) are displayed in Table 1. Differences between groups existed by age, menopausal status (higher sHER2 levels in patients ≥50 years and post-menopausal), and hormone receptor status (lower sHER2 in hormone receptor positive tumors). Table 1 compares characteristics of patients with and without a baseline blood sample to assess sHER2 levels. Caucasians and patients with tumors <2 cm were more likely to have a blood sample available.

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics by sHER2 group at baseline.

| Characteristic | sHER2 <15 N=2029 (88) No. Patient (%) |

Chi-square p-value |

sHER2 ≥15 N=289 (12) No. Patient (%) |

Cohort Patients N=2318 (74) No. Patient (%) |

Chi-square p-value |

Non-Cohort Patients N=815 (26) No. Patient (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Age (median) | 49 (19–82) | 53 (23–80) | 49 (19–82) | 50 (22–79) | ||

|

| ||||||

| Age Group: | ||||||

| <40 | 373 (18) | <0.0001* | 26 (9) | 399 (17) | 0.15* | 145 (18) |

| 40–49 | 691 (34) | 85 (29) | 776 (33) | 261 (32) | ||

| 50–59 | 669 (33) | 113 (39) | 782 (34) | 238 (29) | ||

| ≥ 60 | 296 (15) | 65 (22) | 361 (16) | 171 (21) | ||

|

| ||||||

| Race: | ||||||

| White | 1723 (85) | 0.08 | 234 (81) | 1957 (84) | 0.05 | 664 (81) |

| Other | 306 (15) | 55 (19) | 361 (16) | 151 (19) | ||

|

| ||||||

| Menopausal Status: | ||||||

| Pre-menopausal or < 50 | 1147 (57) | <0.0001 | 107 (37) | 1254 (54) | 0.59 | 432 (53) |

| Post-menopausal or ≥ 50 | 882 (43) | 182 (63) | 1064 (46) | 383 (47) | ||

|

| ||||||

| ER/PR Status: | ||||||

| ER or PR Positive | 1112 (55) | 0.01 | 135 (47) | 1247 (54) | 0.78 | 443 (54) |

| Other | 917 (45) | 154 (53) | 1071 (46) | 372 (46) | ||

|

| ||||||

| Surgery: | ||||||

| Breast Conserving | 796 (39) | 0.77 | 116 (40) | 912 (39) | 0.18 | 299 (37) |

| Mastectomy | 1233 (61) | 173 (60) | 1406 (61) | 516 (63) | ||

|

| ||||||

| Nodal Status: | ||||||

| Positive | 1751 (86) | 0.09 | 260 (90) | 2011 (87) | 0.93 | 706 (87) |

| Negative | 278 (14) | 29 (10) | 307 (13) | 109 (13) | ||

|

| ||||||

| Predominant Histology: | ||||||

| Ductal | 1922 (95) | 0.98± | 274 (95) | 2196 (95) | 0.51± | 767 (94) |

| Lobular | 59 (3) | 8 (3) | 67 (3) | 30 (4) | ||

| Other | 46 (2) | 7 (2) | 53 (2) | 17 (2) | ||

| Missing | 2 (0.1) | 0 (0) | 2 (0.1) | 1 (0.2) | ||

|

| ||||||

| Histologic Tumor Grade (Elston/SBR): | ||||||

| Well/Intermediate | 589 (29) | 0.12 | 71 (25) | 660 (28) | 0.84 | 235 (29) |

| Poor | 1440 (71) | 218 (75) | 1658 (72) | 580 (71) | ||

|

| ||||||

| Pathologic Tumor Size: | ||||||

| < 2 cm | 705 (35) | 0.07 | 85 (29) | 790 (34) | 0.02 | 242 (30) |

| ≥ 2 cm | 1324 (65) | 204 (71) | 1528 (66) | 573 (70) | ||

|

| ||||||

| Hormonal Treatment: | ||||||

| Yes | 1088 (54) | 0.0002 | 122 (42) | 1210 (52) | 0.77± | 418 (51) |

| No | 930 (46) | 166 (57) | 1096 (47) | 388 (48) | ||

| Missing | 11 (0.5) | 1 (0.3) | 12 (0.5) | 9 (1) | ||

Mantel-Haenszel trend test,

Missing not included in comparison

Within Arms A, B and C, patients with baseline sHER2 ≥15 ng/mL were found to have worse DFS than patients with baseline sHER2 <15 ng/mL (A: HR=1.81, p=0.0014; B: HR=2.08, p=0.0015; C: HR=1.96, p =0.01) (Table 2a). Table 2b displays a DFS multivariate analysis across all 3 treatment arms. sHER2 ≥15 ng/mL remained unchanged (HR=1.95 in both analyses). Similarly, multivariate analyses were performed within each treatment arm and had minimal effect on sHER2 hazard ratios. In regards to hormone receptor status, the association of sHER2 with DFS was present within the ER/PR positive and ER/PR negative subgroups (Table 2b).

Table 2a.

Disease-free survival by treatment arm and baseline sHER2 level

| Arm | sHER2 Group | N=2318 | #Events | HR* | 95% CI | p-value | DFS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 yr | 5 yr | |||||||

|

| ||||||||

| All | <15 | 2029 | 277 | 1 | 87.3 | 81.9 | ||

| ≥15 | 289 | 86 | 1.95 | 1.52–2.49 | <0.0001 | 71.5 | 63.7 | |

|

| ||||||||

| A | <15 | 684 | 117 | 1 | 83.6 | 76.5 | ||

| ≥15 | 111 | 41 | 1.81 | 1.26–2.61 | 0.0014 | 64.7 | 56.1 | |

|

| ||||||||

| B | <15 | 723 | 91 | 1 | 88.1 | 83.4 | ||

| ≥15 | 91 | 25 | 2.08 | 1.32–3.27 | 0.0015 | 76.6 | 67.7 | |

|

| ||||||||

| C | <15 | 622 | 69 | 1 | 90.7 | 86.3 | ||

| ≥15 | 87 | 20 | 1.96 | 1.16–3.33 | 0.01 | 75.3 | 70.0 | |

|

| ||||||||

| All | < 10.0 | 678 | 84 | 1 | 86.7 | 82.2 | ||

| 10.0–11.5 | 536 | 70 | 0.91 | 0.66–1.25 | 0.57 | 88.8 | 84.1 | |

| 11.5–13.5 | 583 | 86 | 1.03 | 0.76–1.40 | 0.83 | 86.6 | 80.4 | |

| ≥ 13.5 | 521 | 123 | 1.57 | 1.19–2.08 | 0.002 | 78.2 | 70.6 | |

Stratified by hormone receptor status and nodal status.

Table 2b.

Disease-free survival multivariate analysis across all 3 treatment arms

| Arm | Covariate | HR* | 95% CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| All | sHER2 ≥15 | 1.95 | 1.52–2.50 | <0.0001 |

| Race | 0.97 | 0.72–1.29 | 0.81 | |

| Menopausal Status | 0.94 | 0.76–1.16 | 0.56 | |

| Histologic Tumor Grade | 1.01 | 0.80–1.29 | 0.92 | |

| Tumor Size ≥ 2 cm | 1.20 | 0.95–1.50 | 0.13 | |

Stratified by hormone receptor status and nodal status.

Analyzing serial sHER2 levels during treatment, the mean loge sHER2 remained constant over time in Arm C (estimated slope=0.003, p=0.43) while the estimated increase per month was 0.010 (loge scale) for Arm B (p=0.07) and 0.022 (loge scale) for Arm A (p=<0.0001). Based on the linear mixed model at 18 months, the mean loge sHER2 was 2.98 (95% CI: 2.88 – 3.08), 2.72 (95% CI: 2.62–2.82) and 2.55 (95% CI: 2.42–2.68) for Arms A, B and C, respectively.

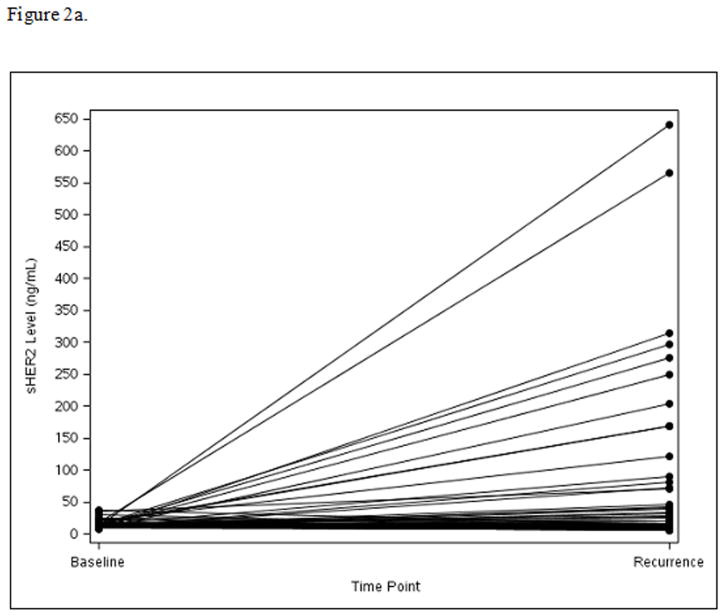

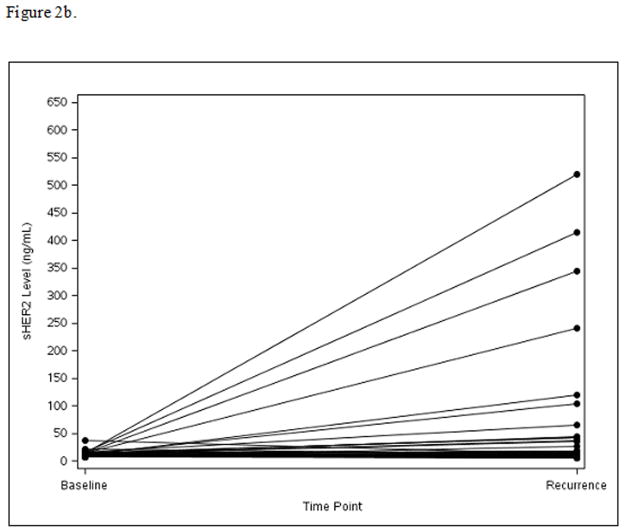

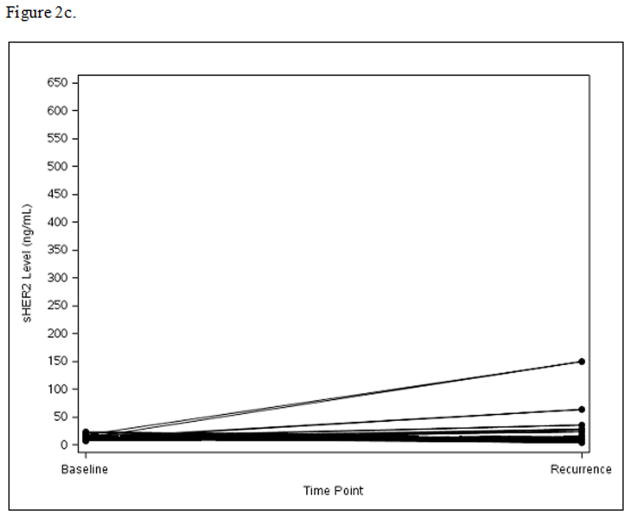

Among the 124 patients with disease recurrence and available serum for this test, sHER2 levels increased from baseline to time of recurrence in Arm A (mean=73.4, median=1.8, p=0.005) (Fig. 2a) and Arm B (mean=48.2, median=2.2, p=0.01) (Fig. 2b), while sHER2 levels remained unchanged in Arm C (mean=9.1, median=−0.3, p=0.66) (Fig. 2c). Patients with recurrence sHER2 levels ≥15 ng/mL had shorter survival time following recurrence with 3-year OS of 51% compared to 77% for the <15 ng/mL sHER2 group (HR=2.36; 95% CI: 1.19–4.70, p=0.01).

Figure 2.

Figure 2a. Panel A: Arm A: Change in sHER2 from Baseline to Recurrence (scale 0 to 650 ng/mL)

Figure 2b. Panel B: Arm B: Change in sHER2 from Baseline to Recurrence (scale 0 to 650 ng/mL)

Figure 2c. Panel C: Arm C: Change in sHER2 from Baseline to Recurrence (scale 0 to 650 ng/mL)

DISCUSSION

Some small studies and subsequent meta-analyses published before the widespread use of HER2-directed therapies have shown a correlation between elevated baseline sHER2 levels and shorter survival in MBC.15,18 Although the clinical importance of soluble HER2 has been studied extensively in metastatic breast cancer, with no consensus as of yet, there are little available data regarding the use of sHER2 in locoregional breast cancer or in the era of multiple anti-HER2 therapies. A prospective study of 256 consecutive stage I–III breast cancer patients demonstrated that high sHER2 levels were found in 9% of patients and its concordance with HER2-positivity in tumor tissue was 87.1%.19 High sHER2 levels were strongly associated with higher stage of disease, higher histological grade, and estrogen and progesterone negative status. Multivariate analysis identified high sHER2 levels as an independent prognostic factor of worse disease-free survival (DFS). Recently, data have been published regarding the potential role of sHER2 in the neoadjuvant setting. In the GeparQuattro study, investigators assessed whether evaluation of a serum marker like sHER2 could help monitor and optimize treatment in 175 patients with early stage breast cancer that participated in this large neoadjuvant clinical trial.20 Soluble HER2 was measured before initiation and after neoadjuvant chemotherapy (pre-surgery) in HER2-positive (n=90) and HER2-negative (n=85) patient cohorts. The study demonstrated a significant positive association between high baseline sHER2 values and pathologic complete response (pCR) at time of surgery in patients with HER2-positive tumors. It also found a similar correlation with a decrease of sHER2 during neoadjuvant chemotherapy. As expected, no such association between sHER2 levels and pCR was observed in the subset of patients with HER2-negative disease. In a follow-up neoadjuvant study, the GeparQuinto, conducted by the same investigators, they noted that higher pre-chemotherapy sHER2 levels (>15 ng/mL) were also associated with higher pCR rates.21 However, sHER2 levels changed differently during neoadjuvant therapy, with higher declines noted in patients treated with trastuzumab than lapatinib. If pCR is the best surrogate of improved long term outcome, then a higher baseline sHER2 would seem to indicate lower recurrence rates down the road for these patients treated with neoadjuvant therapy. This may initially seem contradictory to our finding but the situation of these patients is different. A high baseline sHER2 on the patients in the GeparQuattro and GeparQuinto studies may just reflect higher tumor burden and its decline with neoadjuvant therapy and subsequent achievement of pCR may reflect the population of patients with treatment-sensitive disease. However, our patient population were those whose primary tumors have been resected several weeks earlier and thus a higher baseline sHER2 may represent a population of patients with residual circulating malignant cells that inherently have a higher residual risk of systemic relapse.

The data from the adjuvant early stage HER2-positive breast cancer N9831 translational clinical trial present a unique opportunity for the examination of meaningful associations and trends between clinical outcome and biomarkers of disease. In the N9831 study, 12% of the 2318 women who enrolled in the study after undergoing breast cancer resection, who had serum available and approved for use via written consent, were noted to have baseline elevation of sHER2 (289/2318). This is consistent with the percentages reported previously in the meta-analysis of over 6500 patients reported by Carney et al15 and in the study by Ludovini et al19.

In N9831, higher sHER2 levels were noted in patients ≥50 years, post-menopausal patients, and those with hormone receptor negative status. Whether there is a biological reason for this relationship is unclear. Patients with high baseline levels of sHER2 demonstrated significantly worse DFS in Arm A (standard chemotherapy without trastuzumab) compared to those with normal levels, confirming a prognostic relevance of this marker in HER2-positive breast cancer not treated with trastuzumab. There was also a correlation of elevated baseline sHER2 with worse DFS in patients on Arm C (standard chemotherapy plus concurrent trastuzumab) who had an elevated baseline sHER2 level (HR=1.96; p=0.01). Again, this is in keeping with some of the data published in the metastatic setting, suggesting that patients with elevated sHER2 levels at baseline have inferior outcomes, in this case even when treated with trastuzumab.15,18

It is important to note the differences in trends in sHER2 levels between Arm A (without trastuzumab) and Arm C (with trastuzumab). The sHER2 levels progressively increased in patients who developed tumor recurrence but were not treated with HER2-directed therapy, while remained fairly stable in patients who were treated with concurrent chemotherapy and trastuzumab. This trend persisted in patients with recurrence in both treatment arms. Although this observation is intriguing, the reasons for these data are unclear, and we hope that it will be re-addressed in other data sets (and/or by other investigators). In the meantime we can speculate that there might be biological reasons for these observations, such as considering that trastuzumab therapy may directly inhibit the detection of sHER2. Molina, et al, demonstrated that trastuzumab prevents sHER2 shedding by inhibition of basal and activated HER2 proteolytic cleavage, well before it induces any detectable decrease in cell surface HER2. 22 It is also possible that relapse in patients who did not receive trastuzumab therapy is primarily mediated by the classic HER2 pathway, while patients on the trastuzumab containing arm who experienced progression developed this independently of the HER2 oncoprotein or via alternative pathways that confer acquired resistance to trastuzumab.

Based on the results presented herein, we can conclude that in patients with early stage resected HER2-positive breast cancer, sHER is a prognostic marker associated with shorter DFS and that a high recurrence sHER2 level is predictive of shorter survival. This test may help enhance the prognostic information and thus assist in patient education and further studies (such as including patients with high sHER in studies to further evaluate novel therapeutic strategies to enhance the activity of chemotherapy with trastuzumab).

One of the main auto-critiques of this study is that we started the correlative section with baseline samples from 2318 patients but we were only able to obtain completed serial samples from 105 patients and recurrence samples from only 124 patients. Unfortunately this is a recurring theme with large prospective trials, although our study has the largest matched sets between baseline and recurrent specimens in the adjuvant setting. Patients and participating institutions are initially eager to participate in these collections of samples for correlative sciences but as time goes on, or patients are confronted with updated consents to sign, the number of collections drops significantly. The small sample size at the time of recurrence makes it difficult to draw absolute conclusions as to why sHER2 levels did not increase in patients in Arm C (which is the current standard of care) compared to Arm A.

Our study has been successful as a tool to explore the prognostic and predictive value of sHER in patients with early stage HER2 positive breast cancer in one of the several early pivotal trials of adjuvant trastuzumab, but in no way tries to be a comprehensive review of this test and of its role in the management of such patients. A number of other biomarkers that have shown promise in preclinical models are being evaluated in many of the already completed large adjuvant HER2 clinical trials for their potential to prognosticate risk of disease recurrence and predict response to anti-HER2-based therapies. To date, none of them have reliably been found to be of clinical significance, including p95 HER2 23,24, PTEN 25, PI3-kinase 26,27, topoisomerase IIα 28–31, C-MYC 32, and IGF-1R 33,34. Additional prospective studies are needed to further evaluate the role of soluble HER2 testing in the neoadjuvant, adjuvant and metastatic settings, especially within the context of trials using newer HER2-directed therapies such as lapatinib, pertuzumab, and trastuzumab-emtansine.

Acknowledgments

Support from NIH CA25224 and CA114740, Genentech, Bayer, and the Breast Cancer Research Foundation.

Footnotes

As presented in part at the ASCO Annual Meeting 2009, Abstract # 539.

References

- 1.Ferlay J, Shin HR, Bray F, et al. Estimates of worldwide burden of cancer in 2008: GLOBOCAN 2008. Int J Cancer. 2010 doi: 10.1002/ijc.25516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cianfrocca M, Goldstein LJ. Prognostic and predictive factors in early-stage breast cancer. Oncologist. 2004;9:606–16. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.9-6-606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Slamon DJ, Clark GM, Wong SG, et al. Human breast cancer: correlation of relapse and survival with amplification of the HER-2/neu oncogene. Science. 1987;235:177–82. doi: 10.1126/science.3798106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Romond EH, Perez EA, Bryant J, et al. Trastuzumab plus adjuvant chemotherapy for operable HER2-positive breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:1673–84. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa052122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baselga J, Tripathy D, Mendelsohn J, et al. Phase II study of weekly intravenous recombinant humanized anti-p185HER2 monoclonal antibody in patients with HER2/neu-overexpressing metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1996;14:737–44. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1996.14.3.737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Perez EA, Romond EH, Suman VJ, et al. Four-year follow-up of trastuzumab plus adjuvant chemotherapy for operable human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-positive breast cancer: joint analysis of data from NCCTG N9831 and NSABP B-31. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:3366–73. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.35.0868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Perez EA, Suman VJ, Rowland KM, et al. Two concurrent phase II trials of paclitaxel/carboplatin/trastuzumab (weekly or every-3-week schedule) as first-line therapy in women with HER2-overexpressing metastatic breast cancer: NCCTG study 983252. Clinical breast cancer. 2005;6:425–32. doi: 10.3816/CBC.2005.n.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wolff AC, Hammond ME, Schwartz JN, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology/College of American Pathologists guideline recommendations for human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 testing in breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:118–45. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.2775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Codony-Servat J, Albanell J, Lopez-Talavera JC, et al. Cleavage of the HER2 ectodomain is a pervanadate-activable process that is inhibited by the tissue inhibitor of metalloproteases-1 in breast cancer cells. Cancer Res. 1999;59:1196–201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sias PE, Kotts CE, Vetterlein D, et al. ELISA for quantitation of the extracellular domain of p185HER2 in biological fluids. J Immunol Methods. 1990;132:73–80. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(90)90400-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carney WP, Neumann R, Lipton A, et al. Potential clinical utility of serum HER-2/neu oncoprotein concentrations in patients with breast cancer. Clinical chemistry. 2003;49:1579–98. doi: 10.1373/49.10.1579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hayes DF, Yamauchi H, Broadwater G, et al. Circulating HER-2/erbB-2/c-neu (HER-2) extracellular domain as a prognostic factor in patients with metastatic breast cancer: Cancer and Leukemia Group B Study 8662. Clin Cancer Res. 2001;7:2703–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lennon S, Barton C, Banken L, et al. Utility of serum HER2 extracellular domain assessment in clinical decision making: pooled analysis of four trials of trastuzumab in metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:1685–93. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.16.8351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lipton A, Leitzel K, Ali SM, et al. Human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) extracellular domain levels are associated with progression-free survival in patients with HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer receiving lapatinib monotherapy. Cancer. 2011;117:5013–20. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carney WP, Neumann R, Lipton A, et al. Potential clinical utility of serum HER-2/neu oncoprotein concentrations in patients with breast cancer. Clin Chem. 2003;49:1579–98. doi: 10.1373/49.10.1579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Perez EA, Suman VJ, Davidson NE, et al. Sequential versus concurrent trastuzumab in adjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:4491–7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.36.7045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Payne RC, Allard JW, Anderson-Mauser L, et al. Automated assay for HER-2/neu in serum. Clin Chem. 2000;46:175–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bramwell VH, Doig GS, Tuck AB, et al. Changes over time of extracellular domain of HER2 (ECD/HER2) serum levels have prognostic value in metastatic breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2009;114:503–11. doi: 10.1007/s10549-008-0033-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ludovini V, Gori S, Colozza M, et al. Evaluation of serum HER2 extracellular domain in early breast cancer patients: correlation with clinicopathological parameters and survival. Ann Oncol. 2008;19:883–90. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdm585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Witzel I, Loibl S, von Minckwitz G, et al. Monitoring serum HER2 levels during neoadjuvant trastuzumab treatment within the GeparQuattro trial. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2010;123:437–45. doi: 10.1007/s10549-010-1030-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Witzel I, Loibl S, von Minckwitz G, et al. Predictive value of HER2 serum levels in patients treated with lapatinib or trastuzumab -- a translational project in the neoadjuvant GeparQuinto trial. Br J Cancer. 2012;107:956–60. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2012.353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Molina MA, Codony-Servat J, Albanell J, et al. Trastuzumab (herceptin), a humanized anti-Her2 receptor monoclonal antibody, inhibits basal and activated Her2 ectodomain cleavage in breast cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2001;61:4744–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Scaltriti M, Rojo F, Ocana A, et al. Expression of p95HER2, a truncated form of the HER2 receptor, and response to anti-HER2 therapies in breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007;99:628–38. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djk134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Loibl S, Bruey J, Von Minckwitz G, et al. Validation of p95 as a predictive marker for trastuzumab-based therapy in primary HER2-positive breast cancer: A translational investigation from the neoadjuvant GeparQuattro study. J Clin Oncol (Meeting Abstracts) 2011;29:530. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Perez EA, Dueck AC, Reinholz MM, et al. Effect of PTEN protein expression on benefit to adjuvant trastuzumab in early-stage HER2+ breast cancer in NCCTG adjuvant trial N9831. J Clin Oncol (Meeting Abstracts) 2011;29:10504. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cook JW, Paxinos E, Goodman LJ, et al. Mutations of the catalytic domain of PI3 kinase and correlation with clinical outcome in trastuzumab-treated metastatic breast cancer (MBC) J Clin Oncol (Meeting Abstracts) 2011;29:582. [Google Scholar]

- 27.LoRusso P, Krop IE, Burris HA, et al. Quantitative assessment of diagnostic markers and correlations with efficacy in two phase II studies of trastuzumab-DM1 (T-DM1) for patients (pts) with metastatic breast cancer (MBC) who had progressed on prior HER2-directed therapy. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2010;28:1016. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Burcombe RJ, AMGW, et al. Evaluation of topoisomerase II-alpha as a predictor of clinical and pathological response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in operable breast cancer. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2002;21:1785. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pritchard KI, Messersmith H, Elavathil L, et al. HER-2 and topoisomerase II as predictors of response to chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:736–44. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.4716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Esteva FJ, Hortobagyi GN. Topoisomerase II{alpha} amplification and anthracycline-based chemotherapy: the jury is still out. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:3416–7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.22.6449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Harris LN, Broadwater G, Abu-Khalaf M, et al. Topoisomerase II{alpha} amplification does not predict benefit from dose-intense cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, and fluorouracil therapy in HER2-amplified early breast cancer: results of CALGB 8541/150013. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:3430–6. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.18.4085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Perez EA, Jenkins RB, Dueck AC, et al. C-MYC alterations and association with patient outcome in early-stage HER2-positive breast cancer from the North Central Cancer Treatment Group N9831 adjuvant trastuzumab trial. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:651–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.30.2125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yerushalmi R, Gelmon KA, Leung S, et al. Insulin-like growth factor receptor (IGF-1R) in breast cancer subtypes. Breast cancer Res Treat. 2011 doi: 10.1007/s10549-011-1529-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Reinholz MM, Dueck AC, Chen B, et al. Effect of IGF1R protein expression on benefit to adjuvant trastuzumab in early-stage HER2+ breast cancer in NCCTG N9831 trial. J Clin Oncol (Meeting Abstracts) 2011;29:10503. [Google Scholar]