Abstract

Mastocytosis is a disease with many variants, all of which are characterized by a pathologic increase in mast cells in cutaneous tissue and extracutaneous organs such as the bone marrow, liver, spleen and lymph nodes. The disease presents in two primary age-related patterns: pediatric-onset mastocytosis and adult-onset mastocytosis, which may differ in their clinical manifestations and disease course. Pediatric-onset mastocytosis commonly is diagnosed prior to 2 years of age, and usually consists of cutaneous disease, with urticaria pigmentosa (UP) the most common pattern. The course of pediatric-onset mastocytosis is variable. This is in contrast to adult onset disease which generally presents with systemic findings and increases in extent and severity over time. Because pediatric forms of mastocytosis often differ in presentation and prognosis from adult variants, it is most important to understand pediatric mastocytosis and not rely on adult approaches as a guide on how to identify and manage disease. This is especially important in selecting therapy where antiproliferative agents have a very different set of concerns when used to treat adult mastocytosis compared to pediatric mastocytosis, especially in terms of long-term toxicity. This review is directed at providing age-specific information surrounding the care of the child with mastocytosis.

Keywords: Mastocytosis, pediatric, urticaria pigmentosa, treatment

Introduction

Mastocytosis is a disease with many variants, all of which are characterized by a pathologic increase in mast cells in cutaneous tissue and extracutaneous organs such as the bone marrow, liver, spleen and lymph nodes. The disease presents in two primary age-related patterns: pediatric-onset mastocytosis and adult-onset mastocytosis, which may differ in their clinical manifestations and disease course. Pediatric-onset mastocytosis commonly is diagnosed prior to 2 years of age, and usually consists of cutaneous disease, with urticaria pigmentosa (UP) the most common pattern. The course of pediatric-onset mastocytosis is variable. This is in contrast to adult onset disease which generally presents with systemic findings and increases in extent and severity over time.

The first description of a cutaneous mast cell disease is attributed to Nettleship and Tay in 1869,[1] and was later, because of the gross appearance of the lesions, termed urticaria pigmentosa (UP) by Sangster in 1878.[2] In 1949, Ellis described an autopsy of a fatal case of UP in a one year old child. He documented mast cell infiltrations in the skin, liver, spleen, lymph nodes and bone marrow.[3] There followed many descriptions of variants of mastocytosis organized over the years into classification schemes from Degos in 1963[4] to the contemporary World Health Organization recognized classification.[5–7]

Because pediatric forms of mastocytosis often differ in presentation and prognosis from adult variants, it is most important to understand pediatric mastocytosis and not rely on adult approaches as a guide on how to identify and manage disease. This is especially important in selecting therapy where anti-proliferative agents have a very different set of concerns when used to treat adult mastocytosis compared to pediatric mastocytosis, especially in terms of long-term toxicity. This review is directed at providing age-specific information surrounding the care of the child with mastocytosis.

Presentation of Mastocytosis in Childhood

Mastocytosis in children can present during the neonatal period, in infancy (< 6 months) or childhood (6 months to 16 years). The disease is typically characterized by the presence of increased dermal mast cells and the symptoms are due to the release of mediators and their local and/or systemic actions. Internal organ involvement is not frequent. Sixty to 80% of the patients develop lesions during the first year of life. Lesions of UP, as well as mastocytomas, can be present a birth[8;9]. Based on limited data, it is believe that males and females are equally affected and that no race is predominant. Familial cases are rare and identical twins and triplets have been described [10]. Mast cell mediator related symptoms occur in over 60% of all cases.[11]

The pathogenesis of cutaneous mastocytosis in children is not well understood and many children do not present mutations of c-kit, which codes for KIT, a membrane receptor for stem cell factor expressed in the surface membrane of mast cells, and which is found mutated in the majority of adult patients with systemic mastocytosis.[12] One study reported mutations in c-kit within skin biopsies from 16 out of 37 (43%) pediatric patients with cutaneous disease.[13] These include sporadic mutations at codons 816, 820 and inactivating mutations at codon 839. Missense activating mutations at codon 816 (Asp816 Val and Asp816Phe) have been found in those with UP, mastocytomas and diffuse cutaneous mastocytosis DCM. Patients with the Asp 816Phe mutation appear to acquire the disease earlier than those presenting with Asp 816 Val mutations.[14]

Classification of Cutaneous Mastocytosis in Children

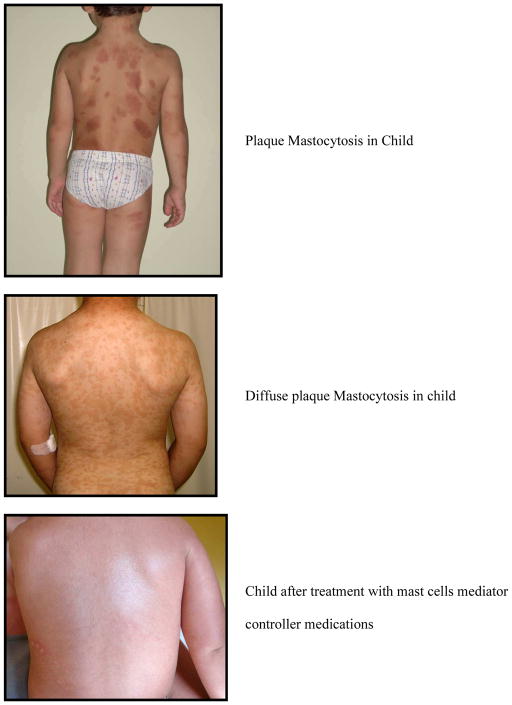

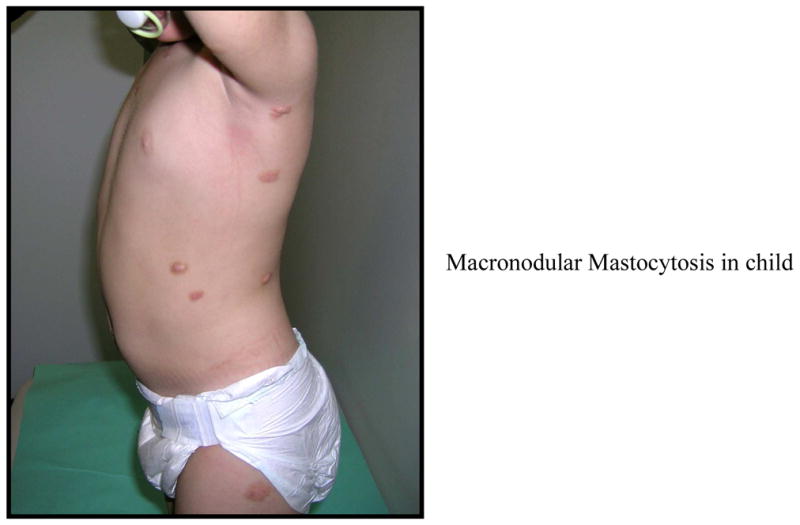

UP is the most common presentation of cutaneous mastocytosis in children and represents 70–90% of the cases. The lesions are red to brown to yellow, measure a few mm to 1–2 cm in diameter, and present as multiple lesions in the form of macules, plaques or nodules (Figures 1, 2, 3). Erythema, swelling and blister formation after stroking or rubbing can occur, and is associated with pruritus and dermatographism. Flushing occurs in up to 36% of the patients with UP. The Darrier’s sign is typically present, with wheal and flare formation after stroking one or several lesions. No scaring occurs. The affected areas include the trunk and extremities (Figure 2). Less affected are palms, soles, scalp and face, as well as sun exposed body areas. In a series of 112 patients, [15] it was reported that the lesions of UP appeared at 2.5 months as a mean, and by age 6 months, 80% of patients had lesions. After the age of 10, the mean time of onset was 26.5 years. Lesions tend to resolve by age 10[11] and if they appear after age 10, they tend to persist and remain symptomatic. [10] Diarrhea and visceral involvement are rare. Wheezing and syncope have been observed.[16] Mastocytomas or nodular lesions occur in 10–35% of the cases of cutaneous mastocytosis in children, and present as one or several lesions that resemble UP but are larger in size, up to several cms in diameter. Such lesions can vesiculate and blister (Figure 1). In a series of 112 patients, [15] solitary mastocytomas were present at birth or developed within one week. Most cases resolve by puberty but persistent lesions have been described in adults.[16] Mastocytomas rarely present with diarrhea, and association with visceral involvement or systemic disease is rare. Flushing can be present and Darrier’s sign is typically positive.

FIGURE 1.

FIGURE 2.

FIGURE 3.

DCM is rare, but can present with more severe symptoms. DCM accounts for 1–3% of the cases of cutaneous mastocytosis, and can involve the whole skin with the central region and scalp most affected DCM can appear at birth (congenital and neonatal) or in early infancy. Blistering and bullae may be the presenting symptoms and the blisters can be hemorrhagic (Figure 1). The skin may be leathery and thickened. Hyperpigmentation may persist into adulthood and dermatographism may be prominent. The first sign may be extensive bullae, which may rupture, leaving erosions and crusts (Figure 1). This form is particularly sensitive to PUVA. There are a few reports of total or partial resolution after PUVA, but remissions generally last only a few months and retreatment is necessary in the majority of the cases. Due to the extent of the lesions and their severity, systemic symptoms can be present due to the large amount of mast cell mediators released locally and absorbed locally and systemically. Whole body flushing, pruritus, diarrhea, intestinal bleeding, hypotension, anemia, hypovolemic shock and deaths have been reported.[17] Visceral involvement with lymphadenopthy and hepatomegaly may be present. A rare complication includes pachydermia.[18]

Telangiectasia macularis eruptiva perstants (TMEP) is the least common form of cutaneous mastocytosis. It rarely presents in childhood. The lesions are characterized by red, telangiectatic macules in a tan or brown background and can co-exist with UP.

Rarely, all cutaneous forms of Mastocytosis in children can present with acute mast cell activation events, including anaphylaxis. Manifestations include whole body flushing, shortness of breath, wheezing, nausea, vomiting diarrhea and /or hypotension. A few cases are associated with cyanotic spells.

Histopathology

In UP, the number of mast cells in the papillary dermis is increased but numbers have not been standardized. Mast cells aggregate around blood vessels, and are sometimes associated with eosinophils.[19] In nodular forms of UP and mastocytomas, mast cells may infiltrate the entire dermis and extend into the subcutaneous tissues. Electron microscopy of the mast cells shows round and spindle-shaped cells that stain with both tryptase and chymase, sometimes in sheet-like distribution. The numbers of mast cells can be as high as 10 times over normal skin.[20] Mast cell numbers are higher in non-lesional skin of patients with UP and mastocytomas than in skin samples from normal controls.

Mast Cell Mediator Related Symptoms

All forms of cutaneous mastocytosis in children can present with associated mast cell-mediator related symptoms due to the local release of mast cell mediators and their local and systemic actions. Demonstration of Darier’s sign characterized by urtication and flare upon rubbing one of the lesions is associated with CM, but is not present in all patients and is thought to be due to the release of histamine, leukotrienes and prostaglandins from skin mast cells. The extent of skin involvement is not directly associated with symptoms and patients with a single mastocytoma or few UP lesions may exhibit significant local and systemic symptoms. Skin symptoms include flushing, pruritus, redness and swelling, which may occur spontaneously or be induced by triggers. Flushing spells are common (20–65%) but hypotension rarely occurs. Acute episodes of cyanosis and respiratory arrest are uncommon. Anaphylactic reactions to hymenoptera stings have been described in adolescents with UP, but the safety and efficacy of immunotherapy in this age category is not known.[21]

Gastrointestinal symptoms can be prominent, with abdominal pain and diarrhea in up to 40% of children. Hyperacidity and peptic ulcers have been reported but peptic ulcer disease is rare in children. Blistering, bullae, prolonged skin bleeding and life-threatening hypotensive episodes are common complications of DCM but are exceptional in UP and those with mastocytomas. Chondroitin sulfate was found in a hemorrhagic blister from a child with DCM,[22] implicating it as a local anti-coagulant. In addition, other products of mast cell activation, such as PAF, PGD2 and histamine, have been isolated from clear blister fluid in a child with DCM.[23] Histamine metabolites have been found elevated in the urine from children with UP and mastocytomas[24] providing evidence of mast cell degranulation.

Correlations Between Cutaneous Involvement, Bone Marrow Infiltration and Serum Tryptase Levels

The initial evaluation of the bone marrow of 17 children where 15 had UP and 2 had DCM, revealed no adult type mast cell aggregates,[8] indicating that in most cases, cutaneous mastocytosis in children does not involve internal organs which precludes the need for routine prognostic bone marrow biopsies. More recently the extent and nature of cutaneous mastocytosis has been studied to understand its association with systemic disease. In a prospective study of 19 children and 48 adult patients with cutaneous mastocytosis, UP was the most common presentation in 17 children. The extent and the density of the lesions were similar in children and adults; however, children presented higher mean and maximum diameter UP lesions as compared to adults. Three children had indolent systemic mastocytosis (ISM), but neither the extent nor the density of UP was predictive of systemic involvement. There was no correlation between skin involvement and duration of disease or the presence of atopy. Serum tryptase was significantly elevated only in children with systemic disease. [25] It appears that neither the extent nor the nature of cutaneous mastocytosis can predict the presence of systemic disease, implying a heterogeneous disease and the need to better understand its pathogenesis.

Tryptase levels correlate with mast cells numbers in the skin; and elevations in tryptase are seen in patients with more severe disease.[26] A retrospective review of 64 patients with mastocytosis (31 children and 33 adults) correlated a severity scoring system with tryptase levels.[27] Twenty children had maculopapular cutaneous mastocytosis, 8 of which had elevated tryptase, 6 children had mastocytomas and 1 had elevated tryptase, and 3 children had DCM, 2 of which had elevated tryptase. None of the children with cutaneous mastocytosis and elevated tryptase had bone marrow findings compatible with systemic mastocytosis, but immunostaining for KIT or tryptase was not done in the majority of the cases nor were c-kit mutations investigated either within the skin lesions or bone marrow biopsies. There was a positive correlation between the extent of skin involved, the physical appearance of the lesions and the presence of associated symptoms such as pruritus, flushing, the presence of Darier’s sign, bone pain and diarrhea and tryptase level. Other mediators such as histamine and N-methyl histamine have been correlated with increased mast cells numbers in the skin [24] but the levels are age dependent in children.

Natural History

There are a few studies available of the natural history of cutaneous mastocytosis in children and which indicate there is a tendency for spontaneous resolution before puberty.[28;29] In a retrospective study[30] of 45 children, which included 34 children with UP and 11 with mastocytomas, the first lesions appeared before the age of 6 months in 41.8% of patients, and before the age of 13 months in 78.2%. No gender differences were seen. UP predominated on the trunk and extremities. Mastocytomas were found only on the extremities. Darier’s sign was positive in 89% of the patients and no differences were seen between patients with UP or mastocytomas. Associated symptoms were seen in 54% of the patients and included itching, flushing, palpitations, angioedema, hypotension and cyanosis. Bullae were frequent in the mastocytoma group. Temperature change was a frequent trigger.

A retrospective study from Mexico reviewed 71 cases of cutaneous mastocytosis of which 53 were UP, 12 had mastocytomas and 6 had DCM. Ninety four % of the patients presented a positive Darier’s sign. In 92% of the cases, disease onset was recorded in the first year of life. Eighty % of patients improved or had spontaneous resolution of disease.[31] The most common presentation was with macules (46), followed by plaques (30) or papules (27), and with bullae in 16 cases. Associated symptoms and signs were absent in those with mastocytomas, except for itching. Diarrhea, was seen in 7 out of 36 cases of UP and 2 out of 5 cases of DCM.

A retrospective review of 180 pediatric patients with mastocytosis from Israel [32] identified 65% with UP, which presented a birth in 20% of the cases and 80% during the first year of life. The distribution included the trunk and extremities. Of the 117 cases of UP, 13 were familial; and of the 5 affected families only one generation was affected. No familial history was found in mastocytomas. The patients were followed for 1 to 15 years; and 75% of those with mastocyomas and 56% of the patients with UP had complete resolution of the lesions. Associated symptoms in those with UP included asthma in 10.3%, flushing in 12.8%, fever in 1.7% and abdominal pain in 2%.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of mastocytosis in children (Table 1) requires a high index of suspicion in a patient with new onset skin lesions with or without mast cell mediator related symptoms. A physical examination with a positive Darier’s sign, serum tryptase, blood count and differential. and a skin biopsy should be done initially. The skin biopsy should be processed and then stained using hematoxilin & eosin and giemsa; and immunostaining for tryptase and KIT. Analysis of c-kit mutations within skin mast cells is recommended. In addition to the skin biopsy, bone marrow studies are recommended if the tryptase is significantly elevated, severe systemic symptoms are present, if there is associated organomegaly or if there is no significant response to initial symptomatic therapy. Once the diagnosis of cutaneous mastocytosis is established, follow-up is scheduled every 6 to 12 months. Parents should be informed about the possibility of evolution to a systemic form in a minority of cases.

Table 1.

Diagnostic Approach in Pediatric Mastocytosis

| For suspected cutaneous mastocytosis (multiple or single lesions) |

| Skin biopsy (3 mm punch): histology, mutational studies if possible |

| Compatible with diagnosis: aggregates of >20 mast cells +/− abnormal morphology, +D816V c-kit |

| If single lesion: mastocytoma, no further studies required |

| If UP, TEMP or other forms diagnosed, need: |

| Selected laboratory tests: peripheral blood count, differential and platelet count; routine biochemistries as required; baseline serum tryptase |

| Studies can be repeated every 6 to 8 months. If severe MC-mediator related symptoms are present, analytical studies may be repeated more frequently |

| Abdominal ultrasound if organomegaly suspected or with: |

| Severe systemic mast cell-mediators related symptoms: |

| GI, flushing, syncope or pre-syncope, cyanotic spells |

| Persistence of skin lesions after puberty |

| Clinical changes suggestive of systemic involvement |

| Bone marrow biopsy and aspirate if: |

| Severe recurrent systemic mast cell-mediators related symptoms: |

| GI, flushing, syncope or pre-syncope, cyanotic spells |

| Organomegaly or significant lymphadenopathy |

| Persistence of skin lesions after puberty |

| Clinical changes suggestive of systemic involvement |

General Concepts in the Management of Pediatric Mastocytosis

Treatment (Table 2) is aimed at suppressing skin and systemic mast cell mediator related symptoms. Symptoms are usually more severe in the first 6 to 18 months after the onset of lesions; and can appear spontaneously or after specific triggers (Table 3). In a very few cases, symptoms can be life-threatening, but satisfactory management with mast cell-mediator controller medications is frequent and is encouraging of a favorable outcome and a good long-term prognosis.

Table 2.

Treatment of Pediatric Mastocytosis

| A. Avoidance of Triggers |

| Specific foods, medications, allergens; and general triggers (Table 3) |

| Physical measures |

| Avoid sudden changes of temperature. |

| Avoid extreme temperatures in bath/shower, swimming pool, air conditioned. |

| Avoid dryness of skin |

| Avoid rubbing |

| Local care of skin |

| Take steps to avoid drying of skin and use skin moisturizer |

| Water-soluble sodium cromolyn cream |

| Apply two to four times a day for urticaria, pruritus, vesicles or bullae. Do not use on denudated lesions (consider topical antibiotics) |

| Topical corticosteroid cream |

| In diffuse lesions apply bath or sterile gauze with zinc sulfate |

| 1. Solitary mastocytoma |

| Water-soluble sodium cromolyn cream: |

| Corticosteroid cream. |

| Avoid friction and pressure |

| Consider surgical excision (flexures, soles, palms, scalp) |

| 2. UP and other forms |

| Trigger (s)-related symptoms |

| Avoidance of triggers |

| H1 antihistamines |

| H2 antihistamines |

| Continuous moderate symptoms |

| Scheduled non-sedating H1 antihistamines; if necessary add sedating H1 antihistamines at demand |

| Scheduled or at demand H2 antihistamines |

| Oral disodium cromolyn in case of persistence of symptoms |

| Severe symptoms |

| Scheduled non-sedating H1 antihistamines |

| Scheduled sedating H1 antihistamines |

| Scheduled H2 antihistamines |

| Oral disodium cromolyn |

| Add antileukotrienes in refractory cases |

| 3. Diffuse forms with life-threatening mast cell-mediator related symptoms, bullae and blistering |

| Treatment may require hospitalization and, in some cases, at the Pediatric Intensive Care Unit. |

| Local therapy |

| Sterile conditions |

| Topic sodium cromolyn |

| Topic corticosteroids |

| Zinc sulfate |

| Antibiotics in denude areas |

| Systemic therapy |

| Epinephrine if necessary |

| Adequate sedation if necessary |

| Scheduled non-sedating H1 antihistamines |

| Scheduled sedating H1 antihistamines |

| Scheduled H2 antihistamines |

| Oral disodium cromolyn |

| Corticosteroids mainly in cases with associated angioedema or abdominal pain (with or without diarrhea) unresponsive to sodium cromolyn |

| Add antileukotrienes in refractory cases |

| Consider PUVA as an exceptional alternative in cases with persistent episodes of diffuse bullae and blistering unresponsive to anti-mediator therapy |

Table 3.

Triggering Factors in Pediatric Mastocytosis

| Physical stimuli |

| Frequent |

| Heat |

| Sudden changes of temperature |

| Rubbing/pressure of skin lesions |

| Scalp trauma (children with scalp involvement) |

| Infrequent |

| Cold |

| Sunlight |

| Emotional factors |

| Stress, |

| Anxiety |

| Sleep deprivation |

| Infectious diseases with fever |

| Viral (Esp. respiratory and gastrointestinal) |

| Bacterial (bronchitis, pneumonia) |

| Drugs* |

| Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs |

| Morphine and derivatives |

| Cough medication: dextromethorphan |

| Miscellaneous |

| Dental procedures |

| Vaccinations |

| Surgery |

| Associated allergic diseases ** |

1. Responses greatly vary from patient to patient. 2. Patients with known sensitivities must wear a Medic alert bracelet or necklace.

If patients have not taken these drugs before, provocation test may be performed under close medical supervision.

Foods, environmental allergens and other factors may exacerbate or precipitate mast cell activation in mastocytosis patients.

Before starting therapy, the type and extent of skin lesions should be recorded along with a baseline serum tryptase. Elevated levels of tryptase, higher than 20 ug/L, and progressively more concerning as values are found at even greater levels, indicate an increased mast cell burden and/or extensive level of degranulation and close observation, evaluation and perhaps hospitalization may sometimes be required. Because of the generally benign nature of cutaneous disease and the high rate of spontaneous regression, cytoreductive therapy is strongly discouraged except in selected cases with life-threatening aggressive variants of mastocytosis

Education of parents and care providers is essential. Individualized information, support groups for parents, and informational brochures containing the most frequent asked questions, specific protocols for specific situations and procedures such as infection with fever, vaccinations, dental work, imaging procedures and surgery, have demonstrated value and increase the quality of life of children with mastocytosis. Contact with the community is important, including alerting teachers, nurses and day care workers about the diagnosis, treatment and potential risks in children with mastocytosis. Communication with pediatricians and other doctors will protect children and help prevent life threatening episodes during surgery, imaging procedures with dyes and dental work. It is of great importance to transmit that cutaneous mastocytosis is not a “contagious condition”. .

Treatment

Because of the benign nature of the disease, the primary objective of disease management (Table 2), is to stabilize the release of mast cell mediators and to block their effects in order to control the symptoms and signs of the disease.[33];[34];[35–41] Avoidance of triggering factors (Table 3), treatment of acute mast cell activation events, treatment of chronic mast cell activation and attempts at decreasing mast cell burden are described below and summarized in Table III.

1. Avoidance of triggering factors

Mast cells can be activated in some patients by hot temperatures and, in a lesser extent, by cold temperatures (Table 3). Control of temperature within a reasonable can decrease symptoms in children and, thus, a rationale use of bath, shower, swimming pool and air conditioning can decrease mediator symptoms and, the need for antihistamines. Anxiety and stress should be avoided or controlled.

2. Systemic therapy in pediatric mastocytosis

The need for intensive therapy in pediatric mastocytosis is exceptional. Only 10 cases among 95 children referred to one of authors (LE) Center for Mastocytosis needed treatment as in-patients and three in the Intensive Care Unit for DCM. All had a favorable outcome and no deaths were recorded. During acute mast cell activation attacks involving hypotension, wheezing or laryngeal edema, epinephrine should be administered intramuscularly in a recumbent position. Cyanotic episodes and recurrent anaphylactic attacks should be treated with epinephrine.

H1 antihistamines have been shown to be useful in decreasing pruritus, flushing, urticaria and tachycardia (Table 2).[33;42];[40;41;43;44] Both sedating and non-sedating antihistamines may be used. Diphenhydramine, hydroxyzine, and cetirizine, among other antihistamines, have proven to be useful in children (a complete review of different drugs and their dosage is presented in reference [40]). Possible adverse effects of high doses of H1 antihistamines include cardiotoxicity (reviewed in ref. [45]).

Combined treatment withH1 and H2 antihistamines has been shown to be effective in some cases for controlling severe pruritus and wheal formation.[46–48] H2 antihistamines such as ranitidine or famotidine can be used (depending on the age group) to manage gastric hypersecretion and peptic ulcer disease associated with mastocytosis.[46;49–53] If H2 antihistamines are unable to control gastrointestinal symptoms, proton pump inhibitors may be recommended [40]. Studies are underway to develop drugs that block the H3 histamine receptor.[54–57]

Oral cromolyn sodium has proven to be effective in some children to control diarrhea, abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting.[58–61] Despite its low absorption, cromolyn sodium may be useful in some patients for the treatment of cutaneous symptoms including pruritus [61–63] and reportedly can help with cognitive symptoms in adults.[63] Progressive introduction helps reduce side effects such as headache, sleepiness, irritability, abdominal pain and diarrhea. Water-soluble sodium cromolyn cream [64] as well as aqueous-based sodium cromolyn skin lotion [65] have proven to be effective at decreasing pruritus and flaring of lesions.

Oral methoxypsoralen therapy with long-wave psoralen plus ultraviolet A radiation (PUVA) has been reported to be effective in cases of bullous diffuse cutaneous mastocytosis in children, even in patients with life-threatening MC-mediator release episodes.[66–69] PUVA is most effective in non-hyperpigmented DCM while the response is usually poor in nodular or plaque forms.

Peri-operative considerations

Pediatric patients with cutaneous or systemic mastocytosis may on occasion require diagnostic or therapeutic procedures that require sedation or anesthesia. Because patients with mastocytosis have an increased mast cell burden and mast cells are implicated in the pathophysiology of anaphylaxis, there is justifiable concern that adverse reactions may follow administration of pharmacologic agents administered in the peri-operative period. These concerns are re-enforced by publications listing various opioids, muscle relaxants, analgesics, and volatile anesthetics as agents that may directly or indirectly induce mast cell activation.[70;71] However, the fear of reactions to drugs used in procedures for the benefit of the patient must be evaluated, placed in perspective, and not be allowed to interfere with optimal patient care.

A report of a review of the literature from 1968 to August 2006 using MeSH headings mastocytosis, anesthesia and analgesia, and anaphylaxis has revealed reports of adverse reactions in adults with mastocytosis.[72–76] In contrast to adults, no reports of anesthesia-related deaths[77–81] and few reports of anesthesia-related complications were found relating to children with mastocytosis[80;82] undergoing general anesthesia.[78;80]. The paucity of information available on peri-operative management of children and adolescents with mastocytosis creates a challenge. In three single case reports, patients had uncomplicated anesthetics after pre-medication with H1 antihistamines. [77;79;81] In a fourth case report, the patient was reported to suffer a circulatory arrest. [80] One retrospective series from 1987 consisted of an analysis of 15 children with either UP or a solitary mastocytoma (N=3), who received general anesthesia in a total of 29 procedures.[78] Two patients were pre-medicated with H1 antihistamines and most anesthetics were uncomplicated, although two children had cutaneous eruptions after administration of codeine. A second retrospective series of 22 patients with pediatric mastocytosis (including CM and ISM) from 2008 examined the outcome of the routine anesthetic regimens in the 29 instances employed.[76] Preoperative drug skin testing was not performed and prophylactic antihistamines or corticosteroids not administered. Scheduled maintenance medications were continued. Routine anesthetic techniques were used. Despite the complexity of the disease, the peri-operative courses were uncomplicated and without serious adverse events. Whereas the paucity of reports of anesthesia-related deaths in children with cutaneous mastocytosis may be reassuring, the planning of anesthetics for patients with pediatric mastocytosis should be comprehensive and take into account the increased risk of anaphylaxis.

Several of the drugs used in peri-operative anesthesia (NSAIDS, opioids, sedative hypnotics, and volatile anesthetics) are reported to cause mast cell degranulation with histamine as well as other mediator release. While mast cell degranulation could have profound effects during anesthesia in patients with mastocytosis, studies documenting drug-induced histamine release from mast cells have largely been conducted in vitro or in animals and may not reflect the human response.[83] In limited human studies, muscle relaxants such as d-tubocurarine, tubocurarine, pancurionum and gallamine triethiodide have been reported to be associated with histamine release. However, these agents are seldom used in current anesthesia practice.[84–86] Meperidine and morphine reportedly induce increases in histamine levels in humans more frequently than fentanyl and sulfentanyl.[86] In the 2008 report, the physicians used fentanyl, morphine and meperidine and observed no evidence of hemodynamic lability. The authors are aware of a lethal idiosyncratic reaction to ketorolac in one adult with mastocytosis (unpublished data) and therefore recommend avoidance of ketorolac in adults and children with mastocytosis. Given the potential for drug-induced mast cell degranulation during anesthesia, an understanding of the nature of reported patients’ allergies is a necessity and will guide selection of appropriate agents to administer.

Understanding the general nature of pediatric mastocytosis is also important for care in peri-operative management. In all variants of mastocytosis, skin pressure may provoke local erythema and edema. Non-immunologic stimuli such as wide variations in temperature, stress, or application of tactile pressure may trigger flushing or itching. In patients with DCM, mechanical pressure can sometimes lead to blister formation.[87] Special attention to position and to protection of pressure points thus has to be given to patients with mastocytosis during anesthesia.

Patients may have medication-controlled symptoms of GERD. It is thus prudent to consider the need for rapid sequence induction. Consideration should also be given to evaluating the coagulation profile, as mast cells contain heparin. Consequently, in children with mastocytosis, prothrombin (PT) and partial thromboplastin times (PTT) may be slightly prolonged. Although there were no reports of unexpected bleeding during surgical procedures in patients with mild abnormalities in coagulation profile,[76] measurements of baseline PT and PTT should be considered prior to invasive procedures where blood loss can be expected.

Serum tryptase is constitutively expressed in patients with mastocytosis and is a reflection of extent of mast cell burden. During anaphylaxis, an elevation in serum tryptase level over baseline may be observed within 15 minutes of its onset and last for 2–4 hours. In one study, elevated serum tryptase at baseline did not predict the occurrence of adverse events. However, it is recommended to obtain baseline serum tryptase levels in all patients prior to surgery, as an increase in tryptase levels associated with an adverse event would suggest mast cell activation; helpful for diagnostic purposes.

Routine skin testing to anesthetic drugs, muscle relaxants or opioids prior to anesthetics is an option, but data may be difficult to interpret. According to reports in the literature, skin test results are not reliable predictors of adverse reactions to drugs because some drugs can directly degranulate mast cells in vivo.[88] Moreover, intradermal testing has not been validated in patients without a history of reaction to given drugs, and a positive skin test has not been shown to be 100% predictive of adverse reactions.[88]

Although the spectrum of clinical manifestations of mastocytosis, increased mast cell numbers, and perceived drug sensitivity makes the approach to anesthetic management in these patients more challenging, routine anesthetics may be safely administered to children with pediatric mastocytosis. This approach calls for a thorough understanding of mastocytosis and its manifestations and appropriate use of routine anesthetic techniques in those patients without a previous history of adverse events. Given the nature of pediatric mastocytosis and the potential for anaphylaxis, the authors advocate the administration of incremental, rather than single boluses of needed drugs (opioids, muscle relaxants) known to activate mast cells, and meticulous preparation to treat, albeit rare, possible adverse events during anesthetics. We suggest medically indicated drugs (opioids, muscle relaxants) should not be eliminated from therapeutic consideration in the perioperative period, unless there is a clear prior history of sensitivity. When questions arise over the use of critical drugs, we advise careful a careful challenge be performed ahead of the scheduled procedure beginning with small amounts of agent. Further, when anesthetizing a patient with pediatric mastocytosis, appropriate personnel and resuscitative therapy for emergent use in the event of anaphylaxis must be readily available.

Research needs

Because pediatric mastocytosis in both a rare and sporadic disease, data has been slow to accumulate relating to pathogenesis, natural history, prognostic features, diagnosis and treatment. What is known has been reviewed in this article. To approach these questions, funding of centers of excellence is needed so as to allow the recruitment and study of sufficient patients with various patterns of disease. Prospective studies then need to be implemented to follow these children as they grow to adulthood to allow and understanding of the prognosis of mastocytosis disease variants. Is the classification of mastocytosis in adults applicable to children; what is the meaning of genetic findings of abnormalities in KIT and other critical genes regulating human mast cell growth? What is the experience with sensitivity of drugs used to manage pain and induce anesthesia? Should cytoreductive therapy be instituted and when?

However, this approach takes time, support, and patience. Until such clinical studies are funded and carried forward, individual centers should be encouraged to approach these research issues as best possible. Case reports and small series are to be encouraged, but results should not be generalized because of the complexity and varying patterns of pediatric disease involving mast cells. Aggressive therapy applied to the control of pediatric mastocytosis should be approached with much caution, as the natural history for the majority of children affected is one of continued improvement.

Acknowledgments

This work was in part supported by the Division of Intramural Research, NIAID/NIH.

Reference List

- 1.Nettleship J, Tay W. Rare forms of urticaria. Br Med J. 1869;2:323–4. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sangster A. An anomalous mottled rash, accompanied by pruritus, factitious urticaria and pigmentation, “urticaria pigmentosa (?)”. Trans Clin Soc London. 1878;11:161. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ellis J. Urticaria pigmentosa: a report of a case of autopsy. Arch Pathol. 1949;48:426–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Degos R. Urticaria pigmentosa and other types of mastocytosis; attempted classification of cutaneous mastocytoses. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 1955;46:759–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Valent P, Horny H-P, Escribano L, et al. Diagnostic Criteria and Classification of Mastocytosis: A Consensus Proposal. Leuk Res. 2001;25:603–25. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2126(01)00038-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Valent P, Akin C, Escribano L, et al. Standards and standardization in mastocytosis: consensus statements on diagnostics, treatment recommendations and response criteria. Eur J Clin Invest. 2007;37:435–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.2007.01807.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Horny H-P, Metcalfe DD, Bennet JM, et al. Mastocytosis. In: Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Harris NL, et al., editors. WHO classification of tumours of haematopoietic and lymphoid tissues. Lyon: IARC; 2008. pp. 54–63. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kettelhut BV, Parker RI, Travis WD, Metcalfe DD. Hematopathology of the bone marrow in pediatric cutaneous mastocytosis. A study of 17 patients. Am J Clin Pathol. 1989;91:558–62. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/91.5.558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kettelhut BV, Metcalfe DD. Pediatric mastocytosis. Ann Allergy. 1994;73:197–202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Soter NA. The skin in mastocytosis. J Invest Dermatol. 1991;96:32S–8S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Azana JM, Torrelo A, Mediero IG, Zambrano A. Urticaria pigmentosa: a review of 67 pediatric cases. Pediatr Dermatol. 1994;11:102–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.1994.tb00560.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Worobec AS, Akin C, Scott LM, Metcalfe DD. Cytogenetic abnormalities and their lack of relationship to the Asp816Val c-kit mutation in the pathogenesis of mastocytosis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1998;102:523–4. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(98)70144-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sotlar K, Escribano L, Landt O, et al. One-Step Detection of c-kit Point Mutations Using PNA-Mediated PCR-Clamping and Hybridization Probes. Am J Pathol. 2003;162:737–46. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63870-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yanagihori H, Oyama N, Nakamura K, Kaneko F. c-kit Mutations in patients with childhood-onset mastocytosis and genotype-phenotype correlation. J Mol Diagn. 2005;7:252–7. doi: 10.1016/S1525-1578(10)60552-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Caplan RM. The natural course of urticaria pigmentosa. Analysis and follow-up of 112 cases. Arch Dermatol. 1963;87:146–57. doi: 10.1001/archderm.1963.01590140008002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wolff K, Komar M, Petzelbauer P. Clinical and histopathological aspects of cutaneous mastocytosis. Leuk Res. 2001;25:519–28. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2126(01)00044-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Murphy M, Walsh D, Drumm B, Watson R. Bullous mastocytosis: a fatal outcome. Pediatr Dermatol. 1999;16:452–5. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1470.1999.00116.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Walker T, von KG, Scheurlen W, Dorn-Beineke A, Back W, Bayerl C. Neonatal mastocytosis with pachydermic bullous skin without c-Kit 816 mutation. Dermatology. 2006;212:70–2. doi: 10.1159/000089026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kasper CS, Tharp MD. Quantification of cutaneous mast cells using morphometric point counting and a conjugated avidin stain. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;16:326–31. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(87)70044-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Garriga MM, Friedman MM, Metcalfe DD. A survey of the number and distribution of mast cells in the skin of patients with mast cell disorders. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1988;82:425–32. doi: 10.1016/0091-6749(88)90015-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gonzalez de Olano D, varez-Twose I, Esteban-Lopez MI, et al. Safety and effectiveness of immunotherapy in patients with indolent systemic mastocytosis presenting with Hymenoptera venom anaphylaxis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;121:519–26. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2007.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Asboe-Hansen G, Clausen J. Mastocytosis (Urticaria Pigmentosa) with urinary excretion of hyaluronic acid and chondroitin sulfuric acid. Changes induced by polymyxin B. Am J Med. 1964;36:144–50. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(64)90156-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Macpherson JL, Kemp A, Rogers M, et al. Occurrence of platelet-activating factor (PAF) and an endogenous inhibitor of platelet aggregation in diffuse cutaneous mastocytosis. Clin Exp Immunol. 1989;77:391–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Van Gysel D, Oranje AP, Vermeiden I, De Raadt JD, Mulder PGH, Van Toorenenbergen AW. Value of urinary N-methylhistamine measurements in childhood mastocytosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;35:556–8. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(96)90679-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brockow K, Akin C, Huber M, Metcalfe DD. Assessment of the extent of cutaneous involvement in children and adults with mastocytosis: Relationship to symptomatology, tryptase levels, and bone marrow pathology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;48:508–16. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2003.98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brockow K, Akin C, Huber M, Scott LM, Schwartz LB, Metcalfe DD. Levels of mast-cell growth factors in plasma and in suction skin blister fluid in adults with mastocytosis: Correlation with dermal mast-cell numbers and mast-cell tryptase. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2002;109:82–8. doi: 10.1067/mai.2002.120524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Heide R, van DK, Mulder PG, et al. Serum tryptase and SCORMA (SCORing MAstocytosis) Index as disease severity parameters in childhood and adult cutaneous mastocytosis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2008 doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2008.03005.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hannaford R, Rogers M. Presentation of cutaneous mastocytosis in 173 children. Australas J Dermatol. 2001;42:15–21. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-0960.2001.00466.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kettelhut BV, Metcalfe DD. Pediatric mastocytosis. J Invest Dermatol. 1991;96:15S–8S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Akoglu G, Erkin G, Cakir B, et al. Cutaneous mastocytosis: demographic aspects and clinical features of 55 patients. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2006;20:969–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2006.01696.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kiszewski AE, Duran-Mckinster C, Orozco-Covarrubias L, Gutierrez-Castrellon P, Ruiz-Maldonado R. Cutaneous mastocytosis in children: a clinical analysis of 71 cases. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2004;18:285–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2004.00830.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ben-Amitai D, Metzker A, Cohen HA. Pediatric cutaneous mastocytosis: a review of 180 patients. Isr Med Assoc J. 2005;7:320–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Metcalfe DD. The treatment of mastocytosis: an overview. J Invest Dermatol. 1991;96:55S–6S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Austen KF. Systemic mastocytosis. N Engl J Med. 1992;326:639–40. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199202273260912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Friedman BS, Santiago ML, Berkebile C, Metcalfe DD. Comparison of azelastine and chlorpheniramine in the treatment of mastocytosis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1993;92:520–6. doi: 10.1016/0091-6749(93)90076-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Longley J, Duffy TP, Kohn S. The mast cell and mast cell disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;32:545–61. doi: 10.1016/0190-9622(95)90336-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Apter AJ, Rothe MJ. Referred for management of mastocytosis. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 1997;79:21–6. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)63079-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Golkar L, Bernhard JD. Mastocytosis. Lancet. 1997;349:1379–85. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)07056-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kurosawa M, Amano H, Kanbe N, et al. Heterogeneity of mast cells in mastocytosis and inhibitory effect of ketotifen and ranitidine on indolent systemic mastocytosis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1997;100:S25–S32. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(97)70001-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Worobec AS. Treatment of systemic mast cell disorders. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2000;14:659–87. doi: 10.1016/s0889-8588(05)70301-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Worobec AS, Metcalfe DD. Mastocytosis: Current treatment concepts. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2002;127:153–5. doi: 10.1159/000048189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Metcalfe DD. Clinical advances in mastocytosis: an interdisciplinary roundtable discussion. J Invest Dermatol. 1991;96(suppl):1S–65S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bianchine PJ, Metcalfe DD. Systemic Mastocytosis. In: Kaplan AP, editor. Allergy. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1997. pp. 854–60. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Marone G, Spadaro G, Granata F, Triggiani M. Treatment of mastocytosis: pharmacologic basis and current concepts. Leuk Res. 2001;25:583–94. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2126(01)00039-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhang MQ. Chemistry underlying the cardiotoxicity of antihistamines. Curr Med Chem. 1997;4:171–84. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fenske NA, Lober CW, Pautler SE. Congenital bullous urticaria pigmentosa. Treatment with concomitant use of H1- and H2-receptor antagonists. Arch Dermatol. 1985;121:115–8. doi: 10.1001/archderm.121.1.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Frieri M, Alling DW, Metcalfe DD. Comparison of the therapeutic efficacy of cromolyn sodium with that of combined chlorpheniramine and cimetidine in systemic mastocytosis. Results of a double-blind clinical trial. Am J Med. 1985;78:9–14. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(85)90454-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gasior-Chrzan B, Falk ES. Systemic mastocytosis treated with histamine H1 and H2 receptor antagonists. Dermatologica. 1992;184:149–52. doi: 10.1159/000247526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hirschowitz BI, Groarke JF. Effect of cimetidine on gastric hypersecretion and diarrhea in systemic mastocytosis. Ann Intern Med. 1979;90:769–71. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-90-5-769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Johnson GJ, Silvis SE, Roitman B, Blumenthal M, Gilbert HS. Long-term treatment of systemic mastocytosis with histamine H2 receptor antagonists. Am J Gastroenterol. 1980;74:485–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Berg MJ, Bernhard H, Schentag JJ. Cimetidine in systemic mastocytosis. Drug Intell Clin Pharm. 1981;15:180–3. doi: 10.1177/106002808101500303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Collen MJ, Howard JM, McArthur KE, et al. Comparison of ranitidine and cimetidine in the treatment of gastric hypersecretion. Ann Intern Med. 1984;100:52–8. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-100-1-52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Debeuckelaere S, Schoors DF, Devis G. Systemic mast cell disease: a review of the literature with special focus on the gastrointestinal manifestations. Acta Clin Belg. 1991;46:226–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Goto T, Sakashita H, Murakami K, Sugiura M, Kondo T, Fukaya C. Novel histamine H3 receptor antagonists: Synthesis and evaluation of formamidine and S-methylisothiourea derivatives. Chem Pharm Bull (Tokyo) 1997;45:305–11. doi: 10.1248/cpb.45.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Van Cauwenberge PB, De Moor SEG. Physiopathology of H3-receptors and pharmacology of betahistine. Acta Otolaryngol (Stockh) 1997;117:43–6. doi: 10.3109/00016489709124020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Linney ID, Buck IM, Harper EA, et al. Design, synthesis, and structure-activity relationships of novel non-imidazole histamine H3 receptor antagonists. J Med Chem. 2000;43:2362–70. doi: 10.1021/jm990952j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Blandizzi C, Colucci R, Tognetti M, De Paolis B, Del Tacca M. H3 receptor-mediated inhibition of intestinal acetylcholine release: pharmacological characterization of signal transduction pathways. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2001;363:193–202. doi: 10.1007/s002100000351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Dolovich J, Punthakee ND, MacMillan AB, Osbaldeston GJ. Systemic mastocytosis: control of lifelong diarrhea by ingested disodium cromoglycate. Can Med Assoc J. 1974;111:684–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Soter NA, Austen KF, Wasserman SI. Oral disodium cromoglycate in the treatment of systemic mastocytosis. N Engl J Med. 1979;301:465–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197908303010903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Horan RF, Sheffer AL, Austen KF. Cromolyn sodium in the management of systemic mastocytosis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1990;85:852–5. doi: 10.1016/0091-6749(90)90067-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Haustein UF, Bedri M. Bullous mastocytosis in a child. Hautarzt. 1997;48:127–9. doi: 10.1007/s001050050559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Welch EA, Alper JC, Bogaars H, Farrell DS. Treatment of bullous mastocytosis with disodium cromoglycate. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1983;9:349–53. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(83)70140-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Leaf FA, Jaecks EP, Rodriguez DR. Bullous urticaria pigmentosa. Cutis. 1996;58:358–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Moore C, Ehlayel MS, Junprasert J, Sorensen RU. Topical sodium cromoglycate in the treatment of moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 1998;81:452–8. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)63145-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Stainer R, Matthews S, Arshad SH, et al. Efficacy and acceptability of a new topical skin lotion of sodium cromoglicate (Altoderm) in atopic dermatitis in children aged 2–12 years: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Br J Dermatol. 2005;152:334–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2004.06303.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Smith ML, Orton PW, Chu H, Weston WL. Photochemotherapy of dominant, diffuse, cutaneous mastocytosis. Pediatr Dermatol. 1990;7:251–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.1990.tb01020.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.van Furth AM, van de Rhee HJ, van Zwieten PH, Nauta-Billig S. Congenitale bulleuze urticaria pigmentosa. Tijdschr Kindergeneeskd. 1993;61:58–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Mackey S, Pride HB, Tyler WB. Diffuse cutaneous mastocytosis - Treatment with oral psoralen plus UV-A. Arch Dermatol. 1996;132:1429–30. doi: 10.1001/archderm.132.12.1429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Escribano L, García-Belmonte D, Hernández-González A, Otheo E, Núñez R, Vázquez JL, Quintero S, Gárate MT. Successful Management of a Case of Diffuse Cutaneous Mastocytosis with Recurrent Anaphylactoid Episodes and Hypertension. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2004;113:S335. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Greenblatt EP, Chen L. Urticaria pigmentosa: An anesthetic challenge. J Clin Anesth. 1990;2:108–15. doi: 10.1016/0952-8180(90)90063-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Stellato C, De Paulis A, Cirillo R, Mastronardi P, Mazzarella B, Marone G. Heterogeneity of human mast cells and basophils in response to muscle relaxants. Anesthesiology. 1991;74:1078–86. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199106000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Scott HW, Jr, Parris WC, Sandidge PC, Oates JA, Roberts LJ. Hazards in operative management of patients with systemic mastocytosis. Ann Surg. 1983;197:507–14. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198305000-00002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hosking MP, Warner MA. Sudden intraoperative hypotension in a patient with asymptomatic urticaria pigmentosa. Anesth Analg. 1987;66:344–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Lerno G, Slaats G, Coenen E, Herregods L, Rolly G. Anaesthetic management of systemic mastocytosis. Br J Anaesth. 1990;65:254–7. doi: 10.1093/bja/65.2.254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Borgeat A, Ruetsch YA. Anesthesia in a patient with malignant systemic mastocytosis using a total intravenous anesthetic technique. Anesth Analg. 1998;86:442–4. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199802000-00044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Carter MC, Uzzaman A, Scott LM, Metcalfe DD, Quezado Z. Pediatric mastocytosis: routine anesthetic management for a complex disease. Anesth Analg. 2008;107:422–7. doi: 10.1213/ane.0b013e31817e6d7c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Coleman MA, Liberthson RR, Crone RK, Levine FH. General anesthesia in a child with urticaria pigmentosa. Anesth Analg. 1980;59:704–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.James PD, Krafchik BR, Johnston AE. Cutaneous mastocytosis in children: anaesthetic considerations. Can J Anaesth. 1987;34:522–4. doi: 10.1007/BF03014363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Brodier C, Guyot E, Palot M, David P, Rendoing J. Anesthesia of a child with a cutaneous mastocytosis. Cah Anesthesiol. 1993;41:77–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Tirel O, Chaumont A, Ecoffey C. Circulatory arrest in the course of anesthesia for a child with mastocytosis. Ann Fr Anesth Reanim. 2001;20:874–5. doi: 10.1016/s0750-7658(01)00536-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Nelson LP, Savelli-Castillo I. Dental management of a pediatric patient with mastocytosis: a case report. Pediatr Dent. 2002;24:343–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Macksey LF, White B. Anesthetic management in a pediatric patient with Noonan syndrome, mastocytosis, and von Willebrand disease: a case report. AANA J. 2007;75:261–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Lorenz W. Histamine release in man. Agents Actions. 1975;5:402–16. doi: 10.1007/BF01972656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Basta SJ, Savarese JJ, Ali HH, Moss J, Gionfriddo M. Histamine-releasing potencies of atracurium, dimethyl tubocurarine and tubocurarine. Br J Anaesth. 1983;55 (Suppl 1):105S–6S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.SNIPER W. The estimation and comparison of histamine release by muscle relaxants in man. Br J Anaesth. 1952;24:232–7. doi: 10.1093/bja/24.4.232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Booij LH, Krieg N, Crul JF. Intradermal histamine releasing effect caused by Org-NC 45. A comparison with pancuronium, metocurine and d-tubocurarine. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 1980;24:393–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.1980.tb01568.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Flacke JW, Flacke WE, Bloor BC, Van Etten AP, Kripke BJ. Histamine release by four narcotics: a double-blind study in humans. Anesth Analg. 1987;66:723–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Fisher MM, Baldo BA. Mast cell tryptase in anaesthetic anaphylactoid reactions. Br J Anaesth. 1998;80:26–9. doi: 10.1093/bja/80.1.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]