Abstract

The psychostimulant amphetamine (AMPH) is frequently used to increase catecholamine levels in attention disorders and Positron Emission Tomography (PET) imaging studies. Despite the fact that most radiotracers for PET studies are characterized in non-human primates (NHPs), data on regional differences of the effect of AMPH in NHPs are very limited. The present study examined the impact of AMPH on extracellular dopamine (DA) levels in the medial prefrontal cortex and the caudate of NHPs using microdialysis. In addition to differences in magnitude, we observed striking differences in the temporal profile of extracellular DA levels between these regions that can likely be attributed to differences in the regulation of dopamine uptake and biosynthesis. The present data suggest that cortical DA levels may remain elevated longer than in the caudate which may contribute to the clinical profile of the actions of AMPH.

Keywords: dopamine, medial prefrontal cortex, caudate, microdialysis, rhesus macaque

Introduction

Aside from its prominent role in substance abuse, the psychostimulant AMPH has been extensively used therapeutically in patients with attention deficit disorder (Berman et al. 2009, Dopheide & Pliszka 2009, Swanson et al. 2011). AMPH has long been known to potently release monoamine neurotransmitters, including dopamine (DA) and norepinephrine (NE), in cortical and subcortical regions (Berridge & Devilbiss 2011, Jones et al. 1999, Kuczenski et al. 1995, Solanto 1998, Sulzer et al. 2005). Based on its ability to release cathecholamines, AMPH is frequently used in studies to increase extracellular DA and displace radioligands in PET studies (Laruelle 2000).

The effects of AMPH have been extensively characterized in rodents (Jones et al. 1999, Kuczenski et al. 1995). However, the pharmacokinetics of AMPH in rodents are different from primates, resulting in a functionally different impact of AMPH across species (Cho et al. 2001, Segal & Kuczenski 2006). Furthermore, unlike in rodents, the dopamine transporter, which is a main substrate for the actions of AMPH, is readily detected in the vast majority of DA processes in the prefrontal cortex of NHP (Lewis et al. 2001, Sesack et al. 1998). Consequently, AMPH appears to increase DA levels in rodent cortex at least in part via action on NE transporters (Mazei et al. 2002). Although NHPs tend to be the primary focus of studies used in the characterization of new PET ligands, the characterization of AMPH in non-human primates (NHPs) has been more limited. Due to the close proximity in cortical structure and function between humans and NHPs (Croxson et al. 2005) and the species differences described above, studies in NHPs provide a premier opportunity for validation of PET displacement techniques by more invasive assessments of extracellular neurotransmitter levels as assessed by microdialysis (Breier et al. 1997, Endres et al. 1997, Laruelle et al. 1997, Narendran et al. 2014, Dewey et al. 1993, Saunders et al. 1994, Moghaddam et al. 1993). Of these studies, only one assessed the impact of systemic AMPH on cortical and subcortical DA levels (Moghaddam et al. 1993). The primary focus of most prior studies on AMPH-mediated DA release in relationship to displacement of radiotracers, has been on the impact in the caudate/putamen. However, the kinetics of DA release and uptake in rodents have been demonstrated to differ greatly across dopaminergic terminal regions (Garris & Wightman 1994) and fundamental differences in regulation of DA levels exist between cortical and subcortical regions (Tyler & Galloway 1992, Wolf & Roth 1990). Furthermore, NHP studies have reported differences in monoaminergic synthesis rates across different cortical and subcortical regions (Brown et al. 1979). Given recent attempts to determine cortical DA responses with newer, high affinity PET ligands (Buchsbaum et al. 2006, Narendran et al. 2009, Narendran et al. 2014), it is necessary to compare the dynamics of the AMPH-evoked DA response in the cortex and subcortical regions when comparing PET findings between regions. Although a subset of the present data was included in a figure of our manuscript characterizing the PET ligand FLB-457 (Narendran et al. 2014), no striatal data collected in the same subjects were reported nor was there the opportunity to compare and contrast the regional differences in dynamics of evoked extracellular dopamine permitted by improved techniques and higher temporal resolution of dialysate sampling. Therefore, the present study extends our findings on the effect of AMPH on extracellular levels in the primate prefrontal cortex by comparing it to that in the caudate region. Careful analysis of those levels in both regions over time revealed regional differences in DA dynamics and suggests that the impact of AMPH in the cortex may last longer than in the caudate.

Methods

Five male rhesus macaques (NIH Animal Facility, Poolesville, MD, USA; 10.7±0.3 years old, 9.0±0.3 kg BW) were used as subjects in the present study. Subjects had no prior history of AMPH administration but they had received moderate doses of ethanol in a study at least 18 months prior (Jedema et al. 2011) and (short term) pharmacotherapies used for routine clinical care and surgical procedures. Subjects were single housed and received ad lib water and sufficient monkey chow biscuits (Labdiet 5038, PMI Richmond, IN) and daily fruit supplements to maintain a healthy body weight.

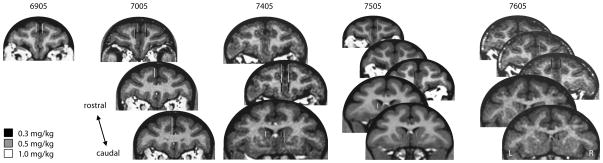

Under isoflurane anesthesia, a polysulfone recording chamber (Crist Instrument, Damascus, MD) was placed at stereotaxic coordinates determined from the subject’s magnetic resonance (MR) images using MonkeyCicerone (Miocinovic et al. 2007); http://www.ciceronedbs.org/). The chamber was secured with dental acrylic and titanium screws to the skull. A post-surgical CT scan confirmed the location of the recording chamber and was co-registered with the MR image to accurately calculate the target location of dialysis probes using MonkeyCicerone. A polysulfone grid (Crist Instrument) was modified and inserted upside down in the recording chamber on the day prior to a microdialysis experiment. Concentric microdialysis probes were constructed as previously described (Bradberry 2000b) and inserted into the brain using the grid while subjects were lightly anesthetized with ketamine (10 mg/kg). Probes were very slowly lowered (~0.5 mm/min) to their target location using a motorized micropositioner (MM-3M-EX; National Aperture, Salem NH). The slower implantation of the dialysis probe is expected to minimize the damage layer surrounding the microdialysis probe thereby providing a more accurate assessment of the actual basal and evoked extracellular neurotransmitter levels (Bungay et al. 2003, Chen 2006). One probe was inserted in the medial aspect of the frontal cortex of each hemisphere, and in a subset of experiments, an additional probe was inserted into the rostral caudate (Fig 1). Probes were always placed in tissue that had not been previously penetrated, on the day prior to sample collection to allow normalization of tissue physiology (Benveniste et al. 1987). A custom-made lid was used on the recording chamber to accommodate the probes while the subject was returned to its cage overnight.

Figure 1.

The active area of the dialysis probe locations for all observations across all 5 subjects (coronal sections in each column are from the same subject). Gray scale indicates the dose of AMPH used at each location. Probes were inserted at the targeted location the day prior to the experimentation.

The present data were collected as part of a study in which amphetamine-induced displacement of tracer doses of the dopamine receptor ligand FLB457 was characterized in anesthetized subjects (Narendran et al. 2014). Therefore, on the day after probe placement, anesthesia was induced by ketamine (20mg/kg) and maintained by isoflurane (1–2.5%) during the PET scan/microdialysis experiment. Data from all successful dialysis experiments are presented regardless whether PET data could be obtained (16/23 experiments). DA measurements were obtained in both cortical and subcortical regions concurrently in 8 (of 12) experiments in which striatal data was collected. The probes were perfused with artificial cerebrospinal fluid (aCSF; 1μl/min) containing (in mM) KCl 2.4, NaCl 137, CaCl2 1.2, MgCl2 1.2, NaH2PO4 0.9, and ascorbate 0.2; pH 7.4). Samples were collected every 10 min starting approximately 2.5 hours following the start of probe perfusion (~3 hrs after sedation). The timing of the samples was not corrected for the small dead volume in the outlet tubing, which was approximately 3.5 μl. Four baseline samples were collected prior to the intravenous (IV) administration of the selected dose of amphetamine (0.15, 0.3, 0.5, or 1.0 mg/kg expressed as free base). Probes were carefully removed at the end of each experiment. Only a single dose of AMPH was given on a single day, and subsequent experiments were performed at least one week apart. All procedures were in accordance with the USPHS Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Pittsburgh.

Samples were analyzed on a HPLC system with electrochemical detection as previously described (Bradberry 2000a). Briefly, 8 μl dialysate was injected by a FAMOS autosampler (LC Packings/Spark Holland) onto a temperature-controlled Spherisorb ODS2 column (100 × 2.1mm, 3μm particle size; Thermo Scientific; Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA, USA) which was being eluted with a mobile phase (8% acetonitrile, 9 g/l NAH2PO4, 0.55 g/l octane sulfonic acid, and 0.005% EDTA; pH 4.5). Electrochemical detection of dopamine was accomplished using an Antec Leyden Intro potentiostat (Antec, Zoeterwoude, The Netherlands) set at a potential of -450 mV. The detection limit of the system was approximately 0.1 fmol/μl dialysate.

Data Analysis

The response to amphetamine was expressed as a percentage of the 3 baseline samples collected prior to injection. Mixed linear model analysis of the post-AMPH samples with dose or region as a factor and time as repeated measure using α=0.05 was performed (SPSS 19) to compare the effect of AMPH across regions. All reported values represent the mean value ± standard error of the mean. The time to peak was calculated for each observation as the time of the dialysis sample with the highest DA level (10 min increments) and averaged across all observations in a each region. The approximate halflife of the increase in DA levels was determined by fitting an exponential decay curve to the average DA levels (expressed at percent baseline) from 50–110min after AMPH injection at each dose.

Results

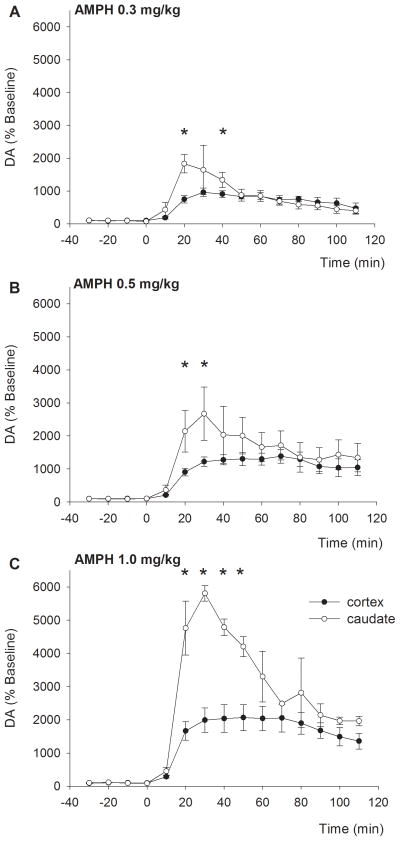

Average baseline DA (uncorrected for probe recovery) in dialysate from the cortex was 0.31±0.03 nM (n=31 observations from a total of 5 subjects). Upon injection of AMPH (0.15, 0.3, 0.5, or 1.0mg/kg), cortical DA levels increased to 593±36 (data not shown), 965±130, 1385±213, or 2067±393 % of baseline levels, respectively (Fig 2A–C, filled symbols).

Figure 2.

The increase in extracellular dopamine levels exhibits a different temporal profile across regions. Upon IV injection of AMPH, DA levels in the cortex (filled symbols) increased slowly, which was followed by a slow decline. In the caudate (open symbols), levels increased rapidly, followed by an initial rapid, and subsequent slower, decline. *p<0.05 between cortex and caudate

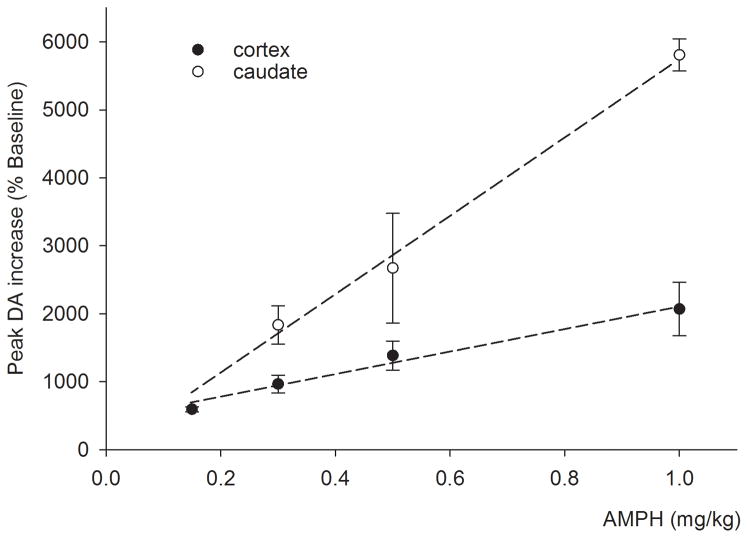

The cortical levels reached their maximum on average 53 ± 4 min following AMPH injection and remained elevated for the duration of the experiment (110 min post AMPH). The maximal increase in cortical DA was dose-dependent (F3,30=4.928, p=0.007) and varied linearly (r2=0.98) with the injected dose in the range examined (Fig 3, filled symbols).

Figure 3.

The peak increase varied linearly with the injected AMPH dose in both the prefrontal cortex (filled symbols) and the caudate (open symbols; R2=0.98 and 0.99, respectively). The slope of the dose response relationship for the caudate is approximately 3.4 times steeper than for the prefrontal cortex.

Average baseline DA in caudate dialysate was 12.9±2.9 nM (n=12 observations from 3 subjects). Injection of AMPH (0.3, 0.5, or 1.0 mg/kg) increased DA to 1834±282, 2670±809, or 5807±235 % of baseline levels, respectively (Fig 2A–C, open symbols). Similar to the cortex, the increase in caudate DA was dose-dependent (F2,11=4.867, p=0.037) and varied linearly (r2=0.99) with the injected dose in the range used (Fig 3, open symbols). The slope of the peak response versus dose was approximately 3.4 times steeper in the caudate than the cortex.

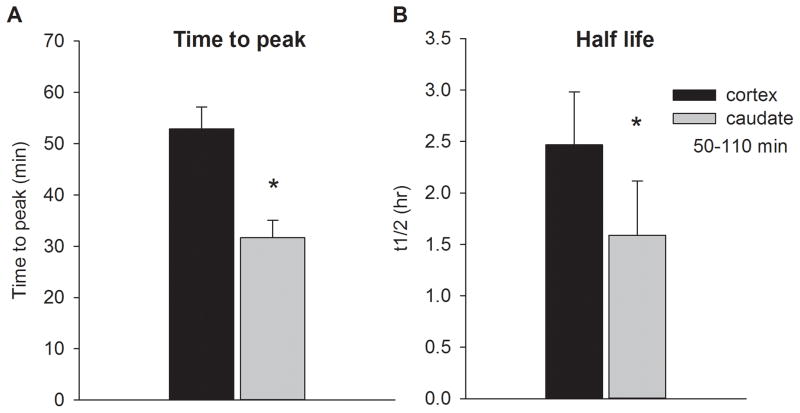

The peak increase in striatal DA was achieved on average 32 ± 3 min following injection of AMPH (Fig 4A). A 2 way ANOVA indicated that the time to reach the peak value was significantly shorter in the caudate regardless of the dose of AMPH (region: F1,42 = 7.446, p = 0.01; dose p = 0.151; region x dose: p = 0.391). Subsequently, caudate DA levels decreased fairly rapidly until they reached levels that were similar (when expressed as percentage of baseline) to elevated cortical levels around 50–70min post injection. Thereafter, caudate and cortical levels declined at a slower rate and remained elevated for the remainder of the experiment. Extrapolation of available data using first order kinetics over the final 70 min (50–110 min after AMPH to minimize the impact of the drug distribution phase following IV injection) determined that the approximate half-life of the AMPH-evoked increase in DA was significantly greater in the cortex compared to the caudate (2.5 ± 0.5 and 1.6 ± 0.5 hrs, respectively; p<0.005; Fig 4B). Average data for individual subjects is provided in Supplementary Table 1.

Figure 4.

(A) The time to peak response was shorter in the caudate compared to the cortex. (B) Half-life of the AMPH-evoked increase in extracellular DA levels was estimated for the last 70 min of the experiment using first order kinetics. The cortical half-life was significantly greater than the half-life in caudate.

* significantly different from cortex.

Discussion

The present study is the first to demonstrate regional differences in dynamics of the systemically administered AMPH-induced increase in DA levels in non-human primates. The linear dose-peak response relationship for both cortex and caudate (Fig 3) demonstrates that the smaller cortical DA response is not simply a result of a ceiling effect of DA efflux in the cortex resulting from tissue depletion. A greater increase in striatal DA compared to cortical DA in response to AMPH has also been observed in rodents (Mazei et al. 2002, Moghaddam et al. 1990, Pehek 1999), but the striking regional differences in time course and the lasting effect of AMPH we observed (Fig 4) were not reported in previous rodent studies. One previous study (Moghaddam et al., 1993) compared the effects of systemic amphetamine in cortex and striatum in non-human primates and observed greater increases in AMPH evoked extracellular DA levels (in absolute terms, and expressed as percent of baseline) in the caudate compared to the cortex, but the prolonged increase in cortical DA levels was not noted. Tissue damage resulting from acute probe implantation causes both basal and evoked dialysate levels to deviate from actual extracellular transmitter levels in undamaged tissue (Bungay et al. 2003). Immediately following implantation, it is likely to elevate basal DA levels as measured by microdialysis, especially in regions such as the cortex, where extracellular levels and reupake are low. In the present study slow probe implantation on the day prior to the experiment was used to minimize tissue damage in close proximity to the probe. Furthermore, current analysis sensitivity permits greater sampling frequency and a more detailed evaluation of the time course of the AMPH effect. These same issues also affected a previous characterization of local infusion of AMPH (Saunders et al. 1994, Endres et al. 1997). Therefore, the present data present a refinement of the older studies which permits an appreciation of the regional differences in the dopaminergic response to AMPH in NHPs.

Although the potential impact of anesthesia on the current findings cannot be ignored, it is important to note that the mechanism of action of AMPH does not rely on neuronal impulse flow and may be less susceptible to the impact of anesthetics. Furthermore, the regional differences in DA dynamics reported here were observed within the same experiment in the majority of cases, making differential impact of anesthesia less likely.

The duration of elevated DA levels we observed in both regions is longer than typically observed in rodents, consistent with the much longer plasma half-life of AMPH in NHPs (~10 hrs; (Downs & Braude 1977) versus rodents ~1hr; (Hutchaleelaha et al. 1994)). The half-life of the evoked DA increase in the caudate was much longer than estimated previously (Endres et al. 1997) likely due to difficulties establishing a stable baseline as described above, but is consistent with the long-lasting behavioral effect of AMPH in NHPs (Downs & Braude 1977). Nevertheless, it does appear that the half-life of AMPH-induced DA increases in both cortex and caudate is shorter than would be expected based on the clearance of plasma levels of AMPH in NHPs. These data are consistent with the acute tolerance to stimulants, both neurochemically and behaviorally, which has been reported previously in NHPs (Bradberry 2000a, Downs & Braude 1977) as well as proposed compensatory mechanisms (Laruelle 2000).

The greater half-life of the DA response in the cortex indicates that despite the much larger peak increase of DA in the caudate, the effect of AMPH in the cortex lasts longer. Such a long lasting effect on cortical DA may in part contribute to the lasting impact of AMPH on behavioral and cognitive processing in humans (Killgore et al. 2009, Killgore et al. 2008, Wesensten et al. 2005). In contrast, previous rodent studies examining the time coure of the effect of AMPH demonstrated that DA returned to baseline levels sooner in the cortex than in the caudate (Pehek 1999). It is not clear whether this is a result of a fundamental species difference (such as a greater potential NE transporter participation in DA uptake in the cortex of rodents) or somehow related to the much more rapid elimination of AMPH in rodents. The notion of a longer lasting effect of AMPH in the NHP cortex is however, consistent with the observation that low dose administration of other psychostimulants such as methylphenidate, exert a predominant effect on cortical catecholamines (Berridge & Devilbiss 2011).

Potential Mechanisms

DA tissue content and the density of terminals and transporters is higher in the caudate compared to the cortex, both in rodents and NHPs (Brown et al. 1979, Moghaddam et al. 1993, Canfield et al. 1990, De Keyser et al. 1989, Kaufman et al. 1991, Sesack et al. 1998, Haber et al. 1995). Consequently, the rate of DA uptake in the caudate is higher than in the cortex (Garris & Wightman 1994, Jones et al. 1999, Brown et al. 1979, Cass & Gerhardt 1995). Given that reverse transport by the DA transporter (DAT) is the main mechanism of AMPH-induced DA release into the extracellular space (Fleckenstein et al. 2007, Sulzer et al. 2005) and that clearance of extracellular DA in the caudate is more dependent on reuptake than in the cortex (Garris & Wightman 1994), the most parsimonious explanation for the higher peak levels of striatal DA is the higher transporter density available for reverse transport coupled with a larger supply of stored DA in caudate compared to the frontal cortex (Pehek 1999, Brown et al. 1979). Similarly, a greater number of transporters may have contributed to the greater increase in DA in the NHP cortex compared to rodents (Lewis et al. 2001, Sesack et al. 1998). Given that we observed temporal differences in the DA response to AMPH, potential mechanisms underlying this effect might be expected to change as a function of time or DA concentration rather than being caused by a stationary difference between the regions, such as a difference in transporter density alone. For example, following AMPH injection in rodents, DA neurons projecting to the caudate exhibit a biphasic response in DA synthesis, with an initial AMPH-induced increase in synthesis followed by synthesis inhibition after approximately 75 min (Tyler & Galloway 1992). In contrast, in the same study cortical DA synthesis is consistently reduced at all time points following AMPH (Tyler & Galloway 1992). If a similar change in DA synthesis occurs in the caudate (but not the cortex) of NHPs, the higher peak and initial steep decline in the caudate DA levels may result from the changing synthesis rate in the caudate. In addition, the lack of such an initial rise in synthesis rate in the cortex may further contribute to the relatively smaller peak increase in cortical DA levels.

Another potential contributor to the differences in time course of AMPH-induced DA levels is internalization of the DA transporter. AMPH administration in vitro causes a concentration-dependent internalization of DAT in HEK293 cells which peaks after 1 hour and reduces DA uptake (Robertson et al. 2009, Saunders et al. 2000). Given the larger increase in striatal DA levels after AMPH, (greater) DAT internalization in the caudate might decrease the rate at which DA can be transferred from the cytosol to the extracellular space via reverse transport. Very little is known about any potential regional differences in the rate of AMPH-induced DAT internalization, but it is clear that DAT internalization would have a large impact on the temporal profile of extracellular levels.

In rodents, DA in the cortex is effectively taken up by the norepinephrine transporter (NET) (Carboni et al. 1990, Gresch et al. 1995, Yamamoto & Novotney 1998) and the NET is also potently affected by the present doses of AMPH (Snyder & Coyle 1969). Furthermore, blockade of the NET has been reported to contribute to the AMPH-induced increase in cortical DA (Mazei et al. 2002) and similar to the DAT, the NET also appears to internalize in response to AMPH (Dipace et al. 2007, Zhu et al. 2000). In primates however, DAT expression is readily apparent in >90% of cortical DA projections (Lewis et al. 2001) and consequently extracellular dopamine levels are expected to be largely determined by DAT reversal and blockade. Little is known about how the time course of AMPH impact on NET compares to that for DAT, but given the absence of NET from the caudate (Smith et al. 2006), a difference in transporter dynamics may have contributed to the different temporal profile of DA we observed across regions.

Implications for imaging studies

PET studies characterizing radioligands frequently report a change in binding potential value and relate this to the peak or average increase above baseline of the extracellular DA levels (Laruelle 2000). The average increase over baseline (or area under the curve (AUC), which is analogous) may better reflect the combined effect of regional differences in peak value and the temporal profile of extracellular DA levels observed in the present study. As described above, peak values in the caudate vary linearly with AMPH dose and they increase approximately 3.4 fold more in the caudate than in the cortex (fig 3). In contrast, the areas under the curve (after AMPH injection) also vary highly linearly with dose (0.99 for both cortex and caudate) and increases only 2.3 fold more in the caudate compared to the cortex (data not shown). Similarly, the peak value or AUC would produce different relationships with changes in binding potential across different doses of AMPH as observed in PET studies. A difference in temporal profile of evoked DA levels may also contribute to different temporal responses observed across regions in pharmacologic magnetic resonance imaging (PhMRI) studies (Jenkins 2012).

In summary, technical advances and improved temporal resolution allowed us to reveal regional differences in extracellular DA levels in response to AMPH in the NHP. These regional difference in response magnitude can likely be attributed to a higher density of the dopamine transporter and larger amounts of stored DA in the caudate. In addition, the difference in temporal profile of the DA response to AMPH is more likely a result of changes in DA synthesis over time or transporter internalization. Despite the greater increase in caudate levels following AMPH, the present data suggest that increased DA levels in the cortex may outlast those in the caudate, which is an important consideration for the therapeutic use of stimulants in attention disorders.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Carol Ehnerd, Kate Gurnsey, Jessica Niccolazzo, and Jessica Porter for their expert technical assistance. These studies were supported by DA026472, DA025636, and a VA Merit Award VA BLR&D 1IO1BX000782.

This work was funded by NIH, NIDA, VA (grant number DA026472, AA0188330, VA Merit Award): This information is usually included already, but please add to the Acknowledgments if not.

Abbreviations

- AMPH

amphetamine

- AUC

area under the curve

- DA

dopamine

- DAT

dopamine transporter

- IV

intravenous

- MR

magnetic resonance

- NE

norepinephrine

- NET

norepinephrine transporter

- NHP

non-human primate

- PET

Positron Emission Tomography

Footnotes

ARRIVE guidelines have been followed: Yes

Conflicts of interest: none

References

- Benveniste H, Drejer J, Schousboe A, Diemer NH. Regional cerebral glucose phosphorylation and blood flow after insertion of a microdialysis fiber through the dorsal hippocampus in the rat. J Neurochem. 1987;49:729–734. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1987.tb00954.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berman SM, Kuczenski R, McCracken JT, London ED. Potential adverse effects of amphetamine treatment on brain and behavior: a review. Mol Psychiatry. 2009;14:123–142. doi: 10.1038/mp.2008.90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berridge CW, Devilbiss DM. Psychostimulants as cognitive enhancers: the prefrontal cortex, catecholamines, and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2011;69:e101–111. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.06.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradberry CW. Acute and chronic dopamine dynamics in a nonhuman primate model of recreational cocaine use. J Neurosci. 2000a;20:7109–7115. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-18-07109.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradberry CW. Applications of microdialysis methodology in nonhuman primates: practice and rationale. Crit Rev Neurobiol. 2000b;14:143–163. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breier A, Su TP, Saunders R, et al. Schizophrenia is associated with elevated amphetamine-induced synaptic dopamine concentrations: evidence from a novel positron emission tomography method. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:2569–2574. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.6.2569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown RM, Crane AM, Goldman PS. Regional distribution of monoamines in the cerebral cortex and subcortical structures of the rhesus monkey: concentrations and in vivo synthesis rates. Brain Res. 1979;168:133–150. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(79)90132-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchsbaum MS, Christian BT, Lehrer DS, Narayanan TK, Shi B, Mantil J, Kemether E, Oakes TR, Mukherjee J. D2/D3 dopamine receptor binding with [F-18]fallypride in thalamus and cortex of patients with schizophrenia. Schizophrenia research. 2006;85:232–244. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2006.03.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bungay PM, Newton-Vinson P, Isele W, Garris PA, Justice JB. Microdialysis of dopamine interpreted with quantitative model incorporating probe implantation trauma. J Neurochem. 2003;86:932–946. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.01904.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canfield DR, Spealman RD, Kaufman MJ, Madras BK. Autoradiographic localization of cocaine binding sites by [3H]CFT ([3H]WIN 35,428) in the monkey brain. Synapse. 1990;6:189–195. doi: 10.1002/syn.890060211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carboni E, Tanda GL, Frau R, Di Chiara G. Blockade of the noradrenaline carrier increases extracellular dopamine concentrations in the prefrontal cortex: evidence that dopamine is taken up in vivo by noradrenergic terminals. J Neurochem. 1990;55:1067–1070. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1990.tb04599.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cass WA, Gerhardt GA. In vivo assessment of dopamine uptake in rat medial prefrontal cortex: comparison with dorsal striatum and nucleus accumbens. J Neurochem. 1995;65:201–207. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1995.65010201.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen KC. Effects of tissue trauma on the characteristics of microdialysis zero-net-flux method sampling neurotransmitters. J Theor Biol. 2006;238:863–881. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2005.06.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho AK, Melega WP, Kuczenski R, Segal DS. Relevance of pharmacokinetic parameters in animal models of methamphetamine abuse. Synapse. 2001;39:161–166. doi: 10.1002/1098-2396(200102)39:2<161::AID-SYN7>3.0.CO;2-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Croxson PL, Johansen-Berg H, Behrens TE, et al. Quantitative investigation of connections of the prefrontal cortex in the human and macaque using probabilistic diffusion tractography. J Neurosci. 2005;25:8854–8866. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1311-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Keyser J, De Backer JP, Ebinger G, Vauquelin G. [3H]GBR 12935 binding to dopamine uptake sites in the human brain. J Neurochem. 1989;53:1400–1404. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1989.tb08530.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dewey SL, Smith GS, Logan J, Brodie JD, Fowler JS, Wolf AP. Striatal binding of the PET ligand 11C-raclopride is altered by drugs that modify synaptic dopamine levels. Synapse. 1993;13:350–356. doi: 10.1002/syn.890130407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dipace C, Sung U, Binda F, Blakely RD, Galli A. Amphetamine induces a calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II-dependent reduction in norepinephrine transporter surface expression linked to changes in syntaxin 1A/transporter complexes. Mol Pharmacol. 2007;71:230–239. doi: 10.1124/mol.106.026690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dopheide JA, Pliszka SR. Attention-deficit-hyperactivity disorder: an update. Pharmacotherapy. 2009;29:656–679. doi: 10.1592/phco.29.6.656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Downs DA, Braude MC. Time-action and behavioral effects of amphetamine, ethanol, and acetylmethadol. Pharmacology, biochemistry, and behavior. 1977;6:671–676. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(77)90093-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endres CJ, Kolachana BS, Saunders RC, Su T, Weinberger D, Breier A, Eckelman WC, Carson RE. Kinetic modeling of [11C]raclopride: combined PET-microdialysis studies. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1997;17:932–942. doi: 10.1097/00004647-199709000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleckenstein AE, Volz TJ, Riddle EL, Gibb JW, Hanson GR. New insights into the mechanism of action of amphetamines. Annual review of pharmacology and toxicology. 2007;47:681–698. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.47.120505.105140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garris PA, Wightman RM. Different kinetics govern dopaminergic transmission in the amygdala, prefrontal cortex, and striatum: an in vivo voltammetric study. J Neurosci. 1994;14:442–450. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-01-00442.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gresch PJ, Sved AF, Zigmond MJ, Finlay JM. Local influence of endogenous norepinephrine on extracellular dopamine in rat medial prefrontal cortex. J Neurochem. 1995;65:111–116. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1995.65010111.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haber SN, Ryoo H, Cox C, Lu W. Subsets of midbrain dopaminergic neurons in monkeys are distinguished by different levels of mRNA for the dopamine transporter: comparison with the mRNA for the D2 receptor, tyrosine hydroxylase and calbindin immunoreactivity. J Comp Neurol. 1995;362:400–410. doi: 10.1002/cne.903620308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutchaleelaha A, Sukbuntherng J, Chow HH, Mayersohn M. Disposition kinetics of d- and l-amphetamine following intravenous administration of racemic amphetamine to rats. Drug metabolism and disposition: the biological fate of chemicals. 1994;22:406–411. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jedema HP, Carter MD, Dugan BP, Gurnsey K, Olsen AS, Bradberry CW. The acute impact of ethanol on cognitive performance in rhesus macaques. Cereb Cortex. 2011;21:1783–1791. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhq244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins BG. Pharmacologic magnetic resonance imaging (phMRI): imaging drug action in the brain. Neuroimage. 2012;62:1072–1085. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.03.075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones SR, Joseph JD, Barak LS, Caron MG, Wightman RM. Dopamine neuronal transport kinetics and effects of amphetamine. J Neurochem. 1999;73:2406–2414. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1999.0732406.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman MJ, Spealman RD, Madras BK. Distribution of cocaine recognition sites in monkey brain: I. In vitro autoradiography with [3H]CFT. Synapse. 1991;9:177–187. doi: 10.1002/syn.890090304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Killgore WD, Kahn-Greene ET, Grugle NL, Killgore DB, Balkin TJ. Sustaining executive functions during sleep deprivation: A comparison of caffeine, dextroamphetamine, and modafinil. Sleep. 2009;32:205–216. doi: 10.1093/sleep/32.2.205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Killgore WD, Rupp TL, Grugle NL, Reichardt RM, Lipizzi EL, Balkin TJ. Effects of dextroamphetamine, caffeine and modafinil on psychomotor vigilance test performance after 44 h of continuous wakefulness. Journal of sleep research. 2008;17:309–321. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2869.2008.00654.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuczenski R, Segal DS, Cho AK, Melega W. Hippocampus norepinephrine, caudate dopamine and serotonin, and behavioral responses to the stereoisomers of amphetamine and methamphetamine. J Neurosci. 1995;15:1308–1317. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-02-01308.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laruelle M. Imaging synaptic neurotransmission with in vivo binding competition techniques: a critical review. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2000;20:423–451. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200003000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laruelle M, Iyer RN, al-Tikriti MS, et al. Microdialysis and SPECT measurements of amphetamine-induced dopamine release in nonhuman primates. Synapse. 1997;25:1–14. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2396(199701)25:1<1::AID-SYN1>3.0.CO;2-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis DA, Melchitzky DS, Sesack SR, Whitehead RE, Auh S, Sampson A. Dopamine transporter immunoreactivity in monkey cerebral cortex: regional, laminar, and ultrastructural localization. J Comp Neurol. 2001;432:119–136. doi: 10.1002/cne.1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazei MS, Pluto CP, Kirkbride B, Pehek EA. Effects of catecholamine uptake blockers in the caudate-putamen and subregions of the medial prefrontal cortex of the rat. Brain Res. 2002;936:58–67. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)02542-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miocinovic S, Zhang J, Xu W, Russo GS, Vitek JL, McIntyre CC. Stereotactic neurosurgical planning, recording, and visualization for deep brain stimulation in non-human primates. J Neurosci Methods. 2007;162:32–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2006.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moghaddam B, Berridge CW, Goldman-Rakic PS, Bunney BS, Roth RH. In vivo assessment of basal and drug-induced dopamine release in cortical and subcortical regions of the anesthetized primate. Synapse. 1993;13:215–222. doi: 10.1002/syn.890130304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moghaddam B, Roth RH, Bunney BS. Characterization of dopamine release in the rat medial prefrontal cortex as assessed by in vivo microdialysis: comparison to the striatum. Neuroscience. 1990;36:669–676. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(90)90009-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narendran R, Frankle WG, Mason NS, et al. Positron emission tomography imaging of amphetamine-induced dopamine release in the human cortex: a comparative evaluation of the high affinity dopamine D2/3 radiotracers [11C]FLB 457 and [11C]fallypride. Synapse. 2009;63:447–461. doi: 10.1002/syn.20628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narendran R, Jedema HP, Lopresti BJ, et al. Imaging dopamine transmission in the frontal cortex: a simultaneous microdialysis and [(11)C]FLB 457 PET study. Mol Psychiatry. 2014;19:302–310. doi: 10.1038/mp.2013.9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pehek EA. Comparison of effects of haloperidol administration on amphetamine-stimulated dopamine release in the rat medial prefrontal cortex and dorsal striatum. The Journal of pharmacology and experimental therapeutics. 1999;289:14–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson SD, Matthies HJ, Galli A. A closer look at amphetamine-induced reverse transport and trafficking of the dopamine and norepinephrine transporters. Mol Neurobiol. 2009;39:73–80. doi: 10.1007/s12035-009-8053-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders C, Ferrer JV, Shi L, et al. Amphetamine-induced loss of human dopamine transporter activity: an internalization-dependent and cocaine-sensitive mechanism. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:6850–6855. doi: 10.1073/pnas.110035297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders RC, Kolachana BS, Weinberger DR. Local pharmacological manipulation of extracellular dopamine levels in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex and caudate nucleus in the rhesus monkey: an in vivo microdialysis study. Experimental brain research Experimentelle Hirnforschung. 1994;98:44–52. doi: 10.1007/BF00229108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segal DS, Kuczenski R. Human methamphetamine pharmacokinetics simulated in the rat: single daily intravenous administration reveals elements of sensitization and tolerance. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006;31:941–955. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sesack SR, Hawrylak VA, Matus C, Guido MA, Levey AI. Dopamine axon varicosities in the prelimbic division of the rat prefrontal cortex exhibit sparse immunoreactivity for the dopamine transporter. J Neurosci. 1998;18:2697–2708. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-07-02697.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith HR, Beveridge TJ, Porrino LJ. Distribution of norepinephrine transporters in the non-human primate brain. Neuroscience. 2006;138:703–714. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.11.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder SH, Coyle JT. Regional differences in H3-norepinephrine and H3-dopamine uptake into rat brain homogenates. The Journal of pharmacology and experimental therapeutics. 1969;165:78–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solanto MV. Neuropsychopharmacological mechanisms of stimulant drug action in attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: a review and integration. Behavioural Brain Research. 1998;94:127–152. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(97)00175-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sulzer D, Sonders MS, Poulsen NW, Galli A. Mechanisms of neurotransmitter release by amphetamines: a review. Prog Neurobiol. 2005;75:406–433. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2005.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanson J, Baler RD, Volkow ND. Understanding the effects of stimulant medications on cognition in individuals with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: a decade of progress. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2011;36:207–226. doi: 10.1038/npp.2010.160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyler CB, Galloway MP. Acute administration of amphetamine: differential regulation of dopamine synthesis in dopamine projection fields. The Journal of pharmacology and experimental therapeutics. 1992;261:567–573. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wesensten NJ, Killgore WD, Balkin TJ. Performance and alertness effects of caffeine, dextroamphetamine, and modafinil during sleep deprivation. Journal of sleep research. 2005;14:255–266. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2869.2005.00468.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf ME, Roth RH. Autoreceptor regulation of dopamine synthesis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1990;604:323–343. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1990.tb32003.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto BK, Novotney S. Regulation of extracellular dopamine by the norepinephrine transporter. J Neurochem. 1998;71:274–280. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1998.71010274.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu MY, Shamburger S, Li J, Ordway GA. Regulation of the human norepinephrine transporter by cocaine and amphetamine. The Journal of pharmacology and experimental therapeutics. 2000;295:951–959. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.