Abstract

Carcinoma cuniculatum (CC) is a rare variant of extremely well differentiated squamous cell carcinoma. We present the clinicopathological features of two cases of CC; one lingual and one esophageal case with a molecular genetic study regarding the TP53 gene mutational status. Case 1 was a 62 year old male with enlarging chronic ulcer in the tongue. Case 2 was a 77 year old male with progressive dysphagia and odynophagia. Both patients were treated surgically. Both tumors showed deeply invaginating, keratin-filled, burrowing crypts lined by very well differentiated squamous epithelium. The esophageal tumor showed varying degrees of reactive nuclear atypia largely limited to the areas with dense intratumoral infiltration of neutrophils. No mutation of TP53 was identified in the esophageal case. Cytologic atypia limited to areas of significant acute inflammation may occur in CC and should, in the absence of aggressive stromal invasion, not preclude a diagnosis of CC.

Keywords: Carcinoma cuniculatum, Verrucous carcinoma, Esophagus, Tongue, TP53, Mutation analysis

Introduction

Carcinoma cuniculatum (CC) is an uncommon variant of extremely well differentiated squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), which was initially described by Aird et al. [1] in 1954. The very well differentiated light microscopic features of this tumor led the authors to label it as “epithelioma cuniculatum”. The most commonly involved site for CC is the skin with a predilection for the sole, but non-cutaneous sites, such as esophagus [2, 3], oral cavity [4, 5], gingiva [6], tongue [7], penis [8], larynx [9] and nail [10] are also on record. CC is histologically typified by deeply invaginating, keratin filled, sinus-like structures which have been likened to rabbit burrows (lat. “cuniculatum”). The squamous epithelium is very well differentiated with minimal if any nuclear atypia. Pure CCs lack aggressive stromal infiltration. There may or may not be an associated exophytic component [2]. The former has led many investigators to view CC and verrucous carcinoma (VC) as two ends of a spectrum of extremely well differentiated SCC, which when pure, only have the capability for local infiltration and lacks metastatic potential [3, 8]. Herein, we present the clinicopathological features of two cases of CC; one lingual and one esophageal case with a molecular genetic study regarding the mutational status of the TP53 gene of the esophageal case. The mutational status of TP53 in CC has, to the best of our knowledge, never been reported previously.

Materials and Methods

The tissue was fixed in formalin, embedded in paraffin, and 4 µm thin sections were cut and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). Special stains, Periodic acid–Schiff (PAS and Grocott methenamine silver (GMS) were performed. An immunohistochemical (IHC) study was performed on both cases; commercially available antibodies: p53 (D0-7) (1:100, monoclonal, DAKO), p16 (clone F12, 1:100 dilution, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA), according to the manufacturers’ protocols were used using the Roche Ventana BenchMark XT autostainer (Ventana Medical Systems, Roche Diagnostics, AZ, USA) and Ventana Ultra View Universal DAB Detection kit (Ventana Medical Systems) with appropriate positive and negative controls.

TP53 Mutation Analysis

Tumor DNA was extracted from 5 mm-thick formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue sections using the DNeasy Blood and Tissue Kit (Qiagen GmbH, Germany).

DNA was amplified by PCR with primers specific for exons 2–11 of TP53 listed in Table 1, using Taq DNA Polymerase (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) and sequenced bidirectionally according to published protocols [11].

Table 1.

Primer sequences and polymerase chain reaction cycling conditions for the p53 fragments used

| Primer name | Forward primer (5′ > 3′) | Reverse primer (5′ > 3′) | Amplicon size (bp) | Tm (°C) | PCR buffer | MgCl2 (mM) | F/R primer conc. (nM) |

dNTPs (μM) |

Taq Pol. (U) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| p53_Exon2_3 | ccaggtgacccagggttg | gcaagggggactgtagatgg | 402 | 62 | 1× | 2.5 | 200 | 200 | 1 |

| p53_Exon4 | acctggtcctctgactgctc | gccaggcattgaagtctcat | 363 | 60 | 1× | 2.0 | 200 | 200 | 1 |

| p53_Exon5_6 | ccgtgttccagttgctttat | ttaacccctcctcccaga | 488 | 58 | 1× | 2.0 | 200 | 200 | 1 |

| p53_Exon7 | tgcttgccacaggtctcc | ccggaaatgtgatgagaggt | 301 | 60 | 1× | 2.5 | 200 | 200 | 1 |

| p53_Exon8_9 | ttccttactgcctcttgctt | agaaaacggcattttgagtg | 411 | 57 | 1× | 2.5 | 200 | 200 | 1 |

| p53_Exon10 | ctcaggtactgtgtatatac | ctatggctttccaacctagga | 218 | 55 | 1× | 4.0 | 200 | 200 | 1 |

| p53_Exon10 (2nd) | ctcaggtactgtgtatatac | gatgagaatggaatcctatg | 233 | 56 | 1× | 4.0 | 200 | 200 | 1 |

| p53_Exon11 | tcatctctcctccctgcttc | ccacaacaaaacaccagtgc | 300 | 60 | 1× | 2.0 | 200 | 200 | 1 |

Tm (°C) temperature; PCR buffer polymerase chain reaction buffer; MgCl 2 (mM) magnesium chloride; F/R primer conc. forward/reverse primer concentration; dNTPs deoxynucleotide triphosphates; Taq Pol. Taq polymerase

Clinical History

Case 1

A 62 year old previously healthy male, with a long smoking history presented with a slowly enlarging chronic left posterolateral lingual ulcer of 6 years duration. The clinical examination revealed a palpable 2 cm ulcerated mass. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed a tumorous lesion measuring 2.4 cm within the left posterolateral aspect of the tongue (Fig. 1a). Two sets of biopsies were performed 3 weeks apart and both were reported as pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia. However, as the clinical suspicion of malignancy was strong, a left hemiglossectomy and an ipsilateral selective (level 1–3) neck dissection were performed. There was no recurrence or metastases documented at 1 year and 6 months post surgery.

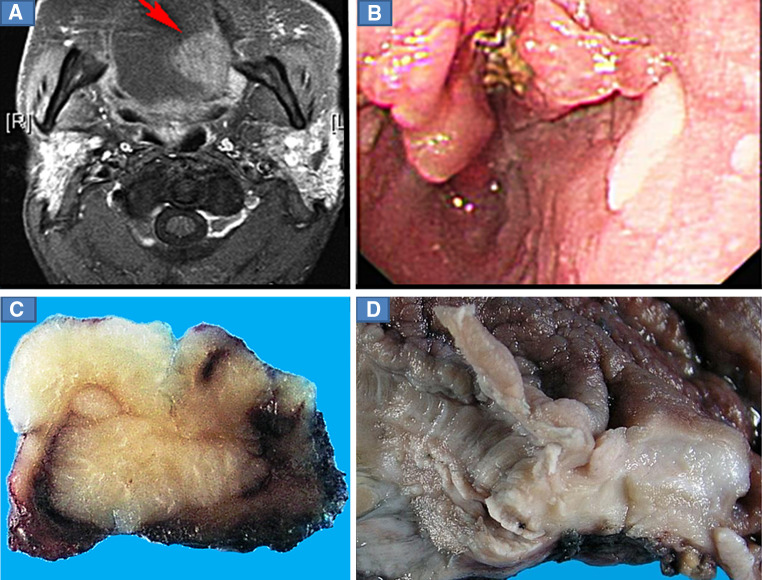

Fig. 1.

a Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showing a well-demarcated tumor at the left posterolateral aspect of the tongue (Case 1). b Endoscopy revealed a raised irregular tumorous lesion in the distal esophagus (Case 2). c Photomicrograph from the deparaffinized surgical specimen of the tongue (sagittal plane) showing a flat, well-demarcated endophytic tumor. d Photomicrograph from the esophagus showing an area of raised thickened mucosal folds and interspersed furrow with a crypt in the esophageal wall

Case 2

A 77 year old male with a long smoking history and a previous stroke presented with a 3 months history of dysphagia with associated weight loss. Endoscopy revealed a raised irregular tumorous lesion in the distal esophagus, focally extending into the cardia (Fig. 1b). Two series of biopsies showed a squamous proliferation with features that were interpreted as reactive hyperplastic changes, but failed to show definitive evidence of malignancy. A computerized tomography (CT) scan confirmed the presence of a tumor at the lower end of the esophagus, which was dilated to 2.5 cm in diameter and over 5 cm in length. A partial esophagectomy was performed. No recurrence or metastases have been documented at 1 year and 2 months follow-up post surgery.

Results

Gross Pathology

The left hemiglossectomy specimen (Case 1) showed a flat endophytic pale solid tumor measuring 2.2 cm in maximum dimension with well demarcated outlines and penetrating deep into the lingual muscles with focal extension to the resection margin (Fig. 1c).

The partial esophagectomy specimen (Case 2) showed a 3.3 cm area of raised thickened mucosal folds and interspersed furrows located over the gastroesophageal junction. Cut sections revealed sinus-like invaginations and crypts in the esophageal wall (Fig. 1d).

Histopathology

Histological examination of the lingual specimen (Case 1) showed varying degrees of surface squamous epithelial acanthosis to pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia, hyperkeratosis and parakeratosis. The tumor displayed a flat surface and formed a central sinus-like structure, which opened into an endophytic complex branching network of crypts (Fig. 2a). These crypts burrowed deep, invading the lingual muscle. In most areas, these crypts showed pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplastic changes with protruding tongue-like structures forming a pseudo-infiltrative growth pattern (Fig. 2b). These keratin filled crypts were lined by very well differentiated squamous epithelium with no significant cytologic/nuclear atypia and there was a well-delineated tumor–stromal interface (Fig. 2c). The crypts were surrounded by a variably intense lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate. Scattered neutrophilic microabscesses and acute inflammatory infiltrate were seen particularly around occasional ruptured keratin containing crypts. Although, as stated above, the nuclear features of the tumor cells were generally bland, there was mild nuclear atypia in the form of some hyperchromasia and pleomorphism limited to these acutely inflamed areas (Fig. 2d). GMS and PAS stains showed fungal organisms; pseudohyphae, resembling Candida both within the crypts and the epithelium. The tumor involved the medial surface of the specimen but additional resection margins were free of tumor. The left selective neck dissection specimen performed contained 29 lymph nodes with no metastasis.

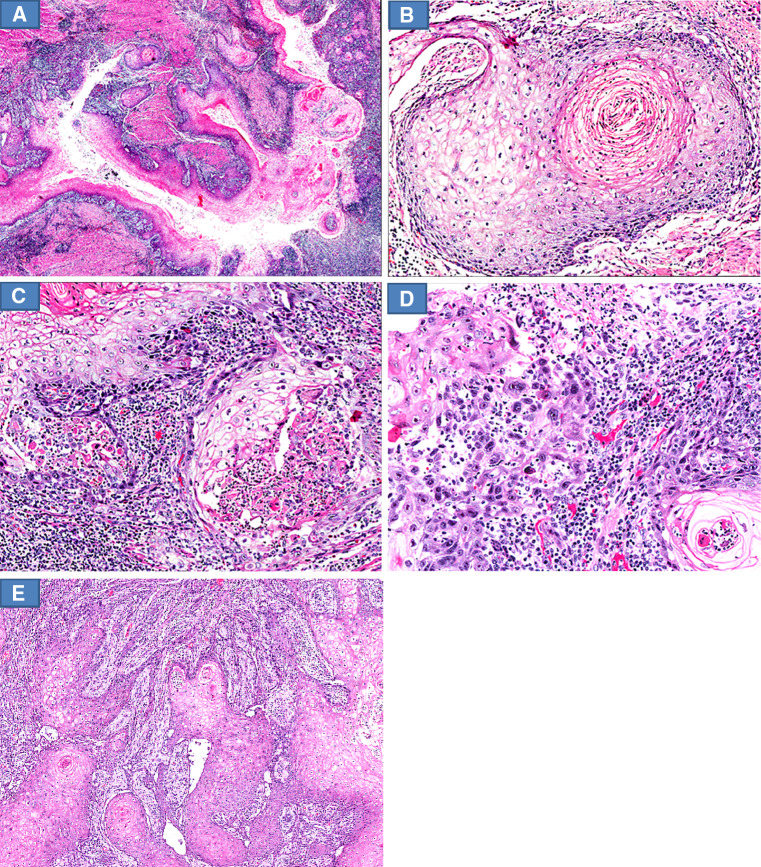

Fig. 2.

Histological features of carcinoma cuniculatum of the tongue. a The flat tumor is composed of an endophytic proliferation of complex branching network of burrowing crypts (whole mount H&E stained section). b Pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia-like features of the crypts with tongue-like pseudo-invasive infiltrative growth pattern (H&E stain: original magnification ×40). c Keratin filled crypt with no acute inflammation lined by well differentiated squamous epithelium with no cytologic atypia and well delineated tumor–stromal interface (H&E stain: original magnification ×200). d Mild cytologic atypia limited to the acutely inflamed areas (H&E stain: original magnification ×400)

Histologic examination of the esophageal tumor (Case 2) showed a neoplasm displaying both exophytic and endophytic components with pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia, hyperkeratosis and dyskeratosis. The deeper part of the tumor was composed of complex burrowing and branching crypts, penetrating deep into the muscularis propria (Fig. 3a). The crypts were lined by very well differentiated squamous epithelium with absent to minimal cytologic atypia (Fig. 3b). The surrounding stroma was inflamed and rich in lymphocytes and plasma cells. Many of the keratin containing crypts, both intact and ruptured were acutely inflamed and contained neutrophilic microabscesses (Fig. 3c). The ruptured keratin crypts also showed a foreign body type giant cellular reaction. In these acutely inflamed areas in particular, a more pronounced cytologic atypia was identified in the basal/peripheral epithelial layer of the squamous-lined crypts. The nuclei were enlarged, hyperchromatic and displayed prominent nucleoli (Fig. 3d). Focally, crypts with pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia displaying a reticulated network of tongue-like epithelial protrusions with a jagged tumor–stromal interface mimicking aggressive stromal invasion were present (Fig. 3e). In these (irregular and acutely inflamed) areas, several mitotic figures were present, but no atypical mitotic figures were identified. The degree of acute inflammation and cytologic atypia was more pronounced than in the lingual case. GMS and PAS stains were negative for fungal organisms. The resection margins were free of tumour. 23 lymph nodes without metastasis were identified.

Fig. 3.

Histological features of carcinoma cuniculatum of the esophagus. a The tumor is composed of deep branching and burrowing crypts (H&E stain: original magnification ×10). b Crypt with no acute inflammation lined by well differentiated squamous epithelium with absent to minimal cytologic atypia (H&E stain: original magnification ×100). c Acutely inflamed intact and ruptured crypts with neutrophilic microabscesses (H&E stain: original magnification ×100). d Pronounced cytologic atypia in the acutely inflamed areas. The basal epithelial cells show nuclear enlargement, nuclear hyperchromasia and conspicuous nucleoli (H&E stain: original magnification ×100). e Crypts with pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia display a reticulated network of tongue-like basal epithelial layer protrusions with a jagged tumor–stromal interface mimicking aggressive stromal invasion (H&E stain: original magnification ×40)

Immunohistochemistry

No immunoreactivity for p16 was present in any of the neoplastic cells in both tumors. In both tumors, weak to moderate nuclear expression of p53 was detected in a minority of the neoplastic cells (data not shown).

TP53 Mutation Analysis (Performed on the Esophageal Case)

No mutations (all exons; 2–11 analyzed) were detected.

Discussion

Carcinoma cuniculatum is a rare form of extremely well differentiated squamous cell carcinoma, which is included as a distinct variant of squamous cell carcinoma in the World Health Organization’s classification of head and neck tumors [12]. CC most often occurs in the skin, but have also been described in other sites, including esophagus [2, 3], oral cavity [4, 5], gingiva [6], tongue [7], penis [8], larynx [9] and nail [10]. In its pure form this neoplasm has only capacity for local infiltrative growth, but not metastasis [3, 8].

Prior to the coining of the term carcinoma cuniculatum, in 1954 Aird et al. [1] labeled this tumor as “epithelioma cuniculatum” and described the salient histopathologic features, namely numerous, complex, deeply invading crypts and sinuses composed of well differentiated keratinizing squamous epithelium imparting a resemblance to the burrows of rabbit’s nests. The terms Buschke–Lowenstein tumor and inverted VC have also been used by some investigators [8].

The etiology of CC has not been firmly established. Rare examples of cutaneous CC have been described in association with long standing neuropathic ulcers secondary to leprosy [13], plantar keratoderma [14] and necrobiosis lipoidica [15]. Etiopathogenetic possibilities that have been discussed by various investigators include smoking, alcohol, reflux and chronic ulcers [2, 3, 16]. A link to human papillomavirus (HPV) type-11 has also been suggested [17]. So far, the association of CC with low risk HPV has been site-specific, being reported only in cutaneous sites [17]. In both our cases, there was no significant expression of p16 on immunohistochemistry, arguing against high risk HPV as an etiological factor. This is in keeping with other reports of CC in extracutaneous sites that have not demonstrated any association with HPV [3]. In the study by Landau et al. [3], analysis of all their esophageal CCs by chromogenic in situ hybridization HPV tested negative for both low and high-risk HPV subtypes.

Reportedly, CC of the oral cavity occurs over a wide age range (9–87 years), with a mean of 50 years and with a male to female ratio of 3:1 [7]. Within the oral cavity, CC has been reported to be located at the gingiva and hard palate but other subsites such as the floor of mouth and buccal mucosa have also been described [18, 19].

CC of the tongue is extremely uncommon with, to the best of our knowledge, only 9 previously documented cases in the English literature, one case by Thavaraj et al. [7] and eight cases by Sun et al. [4]. CC of the esophagus has been described in a series of nine cases by Landau et al. [3] and two cases by De Petris et al. [2, 3]. In the series by Landau et al. [3], the age of the patients ranged from 40 to 73 years with a median age of 62 years.

Given the bland histomorphological features of CC, the diagnosis of this entity, especially on small biopsies, remains challenging and requires a deep enough biopsy to document invasive growth, albeit with a low-grade pattern of invasion and close clinico-radiological correlation. This was reflected in both our cases. In a recent study by Chen et al. [20], the authors presented a semiquantitative scoring system based on the presence or absence of a defined set of histologic features: (1) hyperkeratosis (2) acanthosis (3) dyskeratosis (4) intraepithelial neutrophils (5) neutrophilic microabscesses (6) koilocyte-like cells and (7) the presence of keratin cysts/burrows, in endoscopic esophageal mucosal biopsies from (resection-proven) esophageal CCs. The authors found that this system substantially aided in reaching the correct diagnosis. CC has been reported to show exophytic, endophytic and mixed exophytic and endophytic growth patterns [3]. The lingual tumor in this paper was entirely endophytic whereas the esophageal tumor exhibited both exophytic and endophytic components.

A solely endophytic CC may have an inverted papilloma-like appearance but deep tissue penetration is not seen in the latter. In tumors with a mixed exo-endophytic growth pattern, other verruciform tumors such as classic verrucous carcinoma, mixed verrucous–conventional squamous cell (hybrid) carcinoma, well differentiated squamous cell carcinoma with verrucous features and warty (condylomatous) carcinoma should be considered (see below) [2, 8].

Whether CC and VC are two separate entities or could be perceived as two ends of a spectrum remains controversial. In a recent paper by Kubik et al. [21], the authors took the former position. However, given the fact that several reported extremely well differentiated squamous cell carcinomas (including our esophageal case) have shown both exophytic (verrucous) and endophytic (cuniculatum) features and that no biological or clinical differences between (pure) CC and (pure) VC have been documented, we favor the latter approach. Kubik et al. [21], have advocated to strictly separate CC and VC, i.e., that CCs should not have an exophytic component. For this purpose, the authors made reference to the paper by Aird et al. [1], and presented an illustration from Aird’s original paper (Fig. 3a, b, pp. 245–250), which purportedly showed a “pure” CC in the authors’ opinion. However, in our view this tumor actually also showed an exophytic component.

More important than the discussion of whether CC and VC are strictly separate entities or not (a dispute which carries more of a semantic than clinically relevant and biological flavor), is that these well differentiated squamous neoplasms may contain a component of conventional SCC (as defined by increased nuclear atypia and an aggressive pattern of invasion) and thus constitute hybrid carcinomas. The presence of a component of conventional SCC implies the risk of metastatic behavior. This has been highlighted in a recent study by Sun et al. [4]. The authors showed that lingual and mandibular CCs (similar to VC) may be associated with a component of conventional SCC and that this was associated with metastatic behaviour and even death from metastatic disease [4]. “Well differentiated squamous cell carcinoma with verrucous features” is a designation commonly used for well differentiated squamous cell carcinomas that display a verrucous architecture and where the degree of nuclear atypia and/or the pattern of invasion is deemed to be in excess of what is acceptable for VC/CC. This group of tumors has not been well studied and the biologic behaviour has yet to be established.

Warty carcinoma differs from VC in that it displays, in addition to a verrucous/warty architecture, high-grade cytologic atypia and viral (HPV) cytopathic effect [8]. A particularly challenging differential diagnostic possibility for purely endophytic CCs of the esophagus is esophageal pseudodiverticulosis (EPD) [3]. EPD is characterized by flask shaped outpouchings projecting at right angles to the lumen and can potentially mimic CC both radiologically and endoscopically [3]. However, EPD has not been reported to form a mass lesion, a feature that thus seems to separate this entity from CC. In our esophageal case, the tumor was described as a mass lesion both on endoscopy and radiology.

TP53 is one of the most commonly mutated genes in human cancer and its presence is known to portend a worse outcome in several types of malignant tumors [22]. To date, two studies have reported conflicting results regarding the immunohistochemically detected p53 expression in CC [7]. The mutational status of TP53 of CC has, to the best of our knowledge, never been reported previously. In this report, we have performed p53 immunohistochemical studies on both tumors and also a molecular genetic study regarding the mutational status of the TP53 gene of the esophageal case. For both cases, we could observe limited, weak to moderate, nuclear expression, in some neoplastic cells in the basal/parabasal layers. This corresponds well to the fact that no mutation of TP53 was detected.

The treatment for CC is surgical excision. For cases of CC arising in the oral cavity, a free surgical margin of 5 mm has been recommended [7]. The role of other ancillary treatment modalities such as radiotherapy and chemotherapy is still not well defined.

Patients with pure CC have a good prognosis. In the nine cases of esophageal CC reported by Landau et al. [3] two patients died of postoperative complications, three patients died of causes unrelated to the tumor. No deaths were directly attributed to the tumor in terms of recurrence or metastases. This is in line with both our patients who were well at 1 year and 2 months follow-up for esophageal case and 1 year 6 months for the lingual case.

In both our cases, we have encountered important histological features that further complicated an already challenging diagnosis that are worth highlighting. One feature that is not regularly stressed in the literature is the possible occurrence of beyond mild cytologic atypia in areas of the tumor where there is a significant acute inflammatory component. This was seen in both our cases but particularly prominent in the esophageal case. The acute inflammation and neutrophilic abscesses were seen in intact and ruptured keratin filled cysts. Speculatively, this inflammatory reaction in intact cysts could be caused by either the excess keratin produced by the neoplastic epithelium, superimposed infection or both these factors in combination. The separation of CC with acute inflammation and reactive atypia from a conventional SCC becomes problematic. Another challenging feature from both our cases was the superimposed pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia of both the surface epithelium and the deep burrowing crypts. The extent of squamous epithelial hyperplasia can be florid and potentially misleading even to the experienced pathologist. In our esophageal case, tongue-like protrusions of basal epithelium with jagged tumor–stromal interface coupled with more than mild nuclear atypia in acutely inflamed areas made the distinction from stromal invasion in a conventional SCC extremely challenging. The distinguishing features between CC and its important differential diagnoses are summarized in Table 2. CC has been reported by Sun et al. [4] to show transformation to conventional SCC in the setting of tumor recurrence. Whether the features seen in our esophageal case represents an early transformation to conventional SCC remains, in a strict sense, unknown. However, based on the fact that the worrisome architectural and cytological features were located to the most acutely inflamed areas where evidence of rupture of the crypts/sinuses was focally evident, we favour a diagnosis of pure CC for the esophageal case. Hence, our interpretation was that the cytologic atypia was reactive rather than “neoplastic”. This is, to some extent, supported by the absence of any other—more widespread—features of conventional SCC, the absence of lymph node metastases in a significant number (23) of regional lymph nodes, the uneventful follow-up despite invasion into the esophageal adventitia and by the absence of any mutations in TP53.

Table 2.

Distinguishing features between CC and its important differential diagnoses

| Microscopic features |

Carcinoma cuniculatum | Verrucous carcinoma | Conventional Squamous cell carcinoma | Pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Architecture | Well differentiated squamous lined keratin-filled, burrowing crypts | Mixed exophytic and endophytic growth pattern. Verruciform exophytic component | Solid, irregular nests/islands, squamous pearls may be present | Markedly acanthotic irregular squamous epithelium |

| Invading front | Deeply located cohesive squamous nests and cryptsa | Broad “pushing” infiltration | Aggressive stromal invasion with desmoplastic response | Tongue-like projections of squamous epithelium. Absence of stromal desmoplasia |

| Lymphovascular invasion | Not present | Not present | Possible | Not present |

| Cytologic atypia | Absent to mildb | Absent to mildb | Mild to severe | Absent to mildb |

| Mitotic activity | Variableb | Variableb | Frequent and atypical | Variable, non atypical |

aMay have superimposed pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia, displaying a reticulated network of tongue-like epithelial protrusions resulting in a jagged tumor–stromal interface mimicking aggressive stromal invasion

bThe degree of cytologic atypia and basally confined mitotic activity may be increased in acutely inflamed areas

In our view, the importance of low power evaluation for the characteristic burrowing of keratin filled crypts cannot be overemphasized. In addition, the cytomorphological atypia should be associated with and limited to areas of significant acute neutrophilic inflammation and with no associated aggressive pattern of stromal invasion. If these criteria are not met, a diagnosis of a hybrid carcinoma should be given serious consideration and the prognosis is thus more guarded. The presence of a component of conventional SCC, would most likely also prompt further adjuvant therapy in selected cases.

In summary, we present two rare cases of CC arising in the esophagus and tongue. Due to the bland cytological features and superficial biopsies, both cases presented initial diagnostic difficulties. The limited expression of p16 by the tumor cells argues against an association with high risk HPV and we found no mutation in TP53 in the case analyzed. The presence of cytological atypia in conjunction with and limited to areas of significant acute inflammation and evidence of rupture of crypts/sinuses, not associated with aggressive stromal invasion should not preclude a diagnosis of carcinoma cuniculatum.

References

- 1.Aird I, Johnson HD, Lennox B, Stansfeld AG. Epithelioma cuniculatum: a variety of squamous carcinoma peculiar to the foot. Br J Surg. 1954;42:245–250. doi: 10.1002/bjs.18004217304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.De Petris G, Lewin M, Shoji T. Carcinoma cuniculatum of the esophagus. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2005;9:134–138. doi: 10.1016/j.anndiagpath.2005.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Landau M, Goldblum JR, DeRoche T, et al. Esophageal carcinoma cuniculatum: report of 9 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2012;36:8–17. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3182348aa1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sun Y, Kuyama K, Burkhardt A, Yamamoto H. Clinicopathological evaluation of carcinoma cuniculatum: a variant of oral squamous cell carcinoma. J Oral Pathol Med. 2012;41:303–308. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2011.01116.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fonseca FP, Pontes HA, Pontes FS, et al. Oral carcinoma cuniculatum: two cases illustrative of a diagnostic challenge. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2013;116(4):457–463. doi: 10.1016/j.oooo.2013.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Suzuki J, Hashimoto S, Watanabe K, et al. Carcinoma cuniculatum mimicking leukoplakia of the mandibular gingiva. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2012;39:321–325. doi: 10.1016/j.anl.2011.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thavaraj S, Cobb A, Kalavrezos N, et al. Carcinoma cuniculatum arising in the tongue. Head Neck Pathol. 2012;6:130–134. doi: 10.1007/s12105-011-0270-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barreto JE, Velazquez EF, Ayala E, et al. Carcinoma cuniculatum: a distinctive variant of penile squamous cell carcinoma: report of 7 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2007;31:71–75. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000213401.72569.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Puxeddu R, Cocco D, Parodo G, et al. Carcinoma cuniculatum of the larynx: a rare clinicopathological entity. J Laryngol Otol. 2008;122:1118–1123. doi: 10.1017/S0022215107000163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tosti A, Morelli R, Fanti PA, et al. Carcinoma cuniculatum of the nail apparatus: report of three cases. Dermatology. 1993;186:217–221. doi: 10.1159/000247350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gross E, Kiechle M, Arnold N. Mutation analysis of p53 in ovarian tumors by DHPLC. J Biochem Biophys Methods. 2001;47:73–81. doi: 10.1016/S0165-022X(00)00153-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Johnson N, Franceschi S, Ferlay J, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma. In: Barnes EL, Eveson JW, Reichart P, Sidransky D, et al., editors. World Health Organization classification of tumours: pathology and genetics of head and neck tumours. IARC Press: Lyon; 2005. pp. 168–175. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ramadan WM, EL-Aiat A, Hassan MH. Epithelioma cuniculatum in leprotic foot. Int J Lepr Other Mycobact Dis. 1986;54:127–129. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Affleck AG, Leach IH, Littlewood SM. Carcinoma cuniculatum arising in focal plantar keratoderma. Dermatol Surg. 2007;33:745–748. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2007.33155.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Porneuf M, Monpoint S, Barnéon G, et al. Carcinoma cuniculatum arising in necrobiosis lipoidica. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 1991;118:461–464. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lau P, Li Chang HH, Gomez JA, et al. A rare case of carcinoma cuniculatum of the penis in a 55-year-old. Can Urol Assoc J. 2010;4:E129–E132. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Knobler RM, Schneider S, Neumann RA, et al. DNA dot-blot hybridization implicates human papillomavirus type 11-DNA in epithelioma cuniculatum. J Med Virol. 1989;29:33–37. doi: 10.1002/jmv.1890290107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Delahaye JF, Janser JC, Rodier JF, Auge B. Cuniculatum carcinoma. 6 cases and review of the literature. J Chir. 1994;131:73–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kahn JL, Blez P, Gasser B, et al. Carcinoma cuniculatum. Apropos of 4 cases with orofacial involvement. Rev Stomatol Chir Maxillofac. 1991;92:27–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen D, Goldblum JR, Landau M, et al. Semiquantitative histologic evaluation improves diagnosis of esophageal carcinoma cuniculatum on biopsy. Mod Pathol. 2013;26:806–815. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2012.224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kubik MJ, Rhatigan RM. Carcinoma cuniculatum: not a verrucous carcinoma. J Cutan Pathol. 2012;39:1083–1087. doi: 10.1111/cup.12016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goh AM, Coffill CR, Lane DP. The role of mutant p53 in human cancer. J Pathol. 2011;223:116–126. doi: 10.1002/path.2784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]