Abstract

One challenge faced by many family members caring for persons with dementia is lack of information about how to take care of others and themselves. This is especially important for persons from ethnic minority groups, since linguistically and culturally appropriate information is often not available. In response to these needs, we developed a website for Spanish-speaking caregivers. Cuidatecuidador.com provides bilingual information on dementia and caregiver issues. Content was developed and then evaluated by caregivers residing in three countries. Findings suggest trends that exposure to information may be related to a higher sense of mastery and a reduction of depressive symptomatology.

Keywords: mixed methods, caregiving, dementia, ethnicity and multicultural issues, mental health and mental illness

Approximately five million Americans were diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease or related dementias (ADRD) in 2012 (National Institute on Aging [NIA], 2012). Advanced age is a major risk factor for dementia, with estimates of upwards of forty percent of all persons aged eighty-five and over having a diagnosis of ADRD (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2012). By 2050, Hispanics will account for twenty percent of the elderly population in the U.S. (Federal Interagency Forum on Aging Statistics, 2010). The increase in ADRD with age will result in a large number of Hispanics with this disease in the coming decades. This paper describes the development and assessment of the effectiveness of Cuidate Cuidador – a website that provides online education and support for Hispanic family, and professional caregivers of people with ADRD – in increasing caregivers’ self-efficacy and perceived social support, as well as in decreasing caregiver burden and distress. This project was based on the preliminary findings of a study by Weitzman, Neal, Chen, & Levkoff (2008).

The typical primary caregiver spends between sixty-nine and one hundred and seventeen hours per week providing informal care to persons with ADRD, leaving little time for caregivers to engage in self-care and health-promoting behaviors (Acton, 2002; Willette-Murphy, Todero, & Yeaworth, 2006). It has been well documented that the stress and burden of caregiving negatively impacts the physical and emotional health of dementia caregivers (Etters, Goodball, & Harrison, 2008; Mahoney, Regan, Katona, & Livingston, 2005; Papastavrou, Kalokerinou, Papacostas, Tsangari, & Sourtzi, 2007).

The majority of Hispanic families take on the responsibility of caring for an ADRD family member at home; this undertaking presents significant challenges (Karlawish et al., 2011; Valle, 1994). For example, Hispanic caregivers are less likely to use formal support services, more likely to face language and literacy issues when attempting to access and utilize services, and less likely to find culturally competent services (Karlawish et al., 2011; Levkoff, Levy, & Weitzman, 1999; Pinquart & Sörensen, 2005; Rosenthal Gelman, 2010; Yeo & Gallagher-Thompson, 1996).

Strongly held values of the importance of filial support for parents often prevent many Hispanic caregivers from seeking professional care outside the family (Kane, 2000; Rosenthal Gelman, 2010; Valle, Yamada, & Barrio, 2004). Though Hispanic caregivers view caregiving as both a responsibility and a privilege, at the same time they experience emotional stress, frustration, and isolation (Cox & Monk, 1996; Talamantes & Aranda, 2004).

Research shows that caregivers who participate in a support group report a number of health and social benefits, including reduced depression and feelings of isolation; improved understanding of ADRD and its management; and less fatigue (Biegel, Sales, & Schulz, 1991; Llanque & Enriquez, 2012; Pearlin, Aneshensel, Mullan, & Whitlach, 1997). However, reaching these support groups can be difficult for many caregivers due to distance and their caregiving obligations (Karlawish et al., 2011; Reynoso-Vallejo, Henderson, & Levkoff, 1998).

Use of Technology to Meet Needs

It has been suggested that computer-based technology can be an effective tool to improve emotional well-being (White et al., 2002), physical functioning (Box et al., 2002), and self-esteem (McConatha, McConatha, & Dermigny, 1994) for older adults. Moreover, Internet use can greatly increase social support (Alexy, 2000), thus reducing isolation (Box et al., 2002) and increasing a sense of community (Sum, Mathews, Pourghasem, & Hughes, 2009).

As of 2010, eighty-one percent of U.S.-born Hispanics and fifty-four percent of foreign-born Hispanics who were eighteen and older in the U.S. had used the Internet (Livingston, 2011). In addition, fifty-eight percent of Hispanics ages forty-five through fifty-nine, as well as twenty-nine percent of Hispanics aged sixty and older used the Internet (Livingston, 2011). It is likely that many individuals in the latter age group are caregivers, or will be serving as caregivers in the near future.

Online communities have become an increasingly common way for geographically dispersed groups, which are tied together by a common interest, to meet online for education, support, and social connection (Neal, 2005). To address the unmet educational and social support needs of Hispanic caregivers of persons with dementia, a website – Cuidate Cuidador – was developed and evaluated. The name directly translates to “Caregiver, take care of yourself” and the concept was based upon increasing computer trends of Hispanic online access. Cuidate Cuidador offers culturally competent information about ADRD, in both Spanish and English, practical “how-to” instructions on managing dementia-related behaviors and symptoms, real stories from caregivers, and information for caregivers on how to take care of themselves. The site also has an audio component that offers the option of listening to content in either Spanish or English, for those who face literacy challenges. Other features include a comment section where caregivers can post and interact with other caregivers, an “Ask an Expert” resource section, information on national and international resources, and videos. Cuidate Cuidador aims to transform the current state of the typically isolated, home-based caregiving situation among Hispanic families, into a socially connected Internet-based community. The following sections describe the steps followed to develop the website and the assessment of its effectiveness in increasing knowledge of ADRD, caregivers’ self-efficacy for caregiving (competence), perceived social support, and decreasing caregiver burden and emotional distress.

Methods

Spanish-language content was developed for the website by native speakers from Puerto Rico and then translated into English, guided by a team with expertise in ADRD, caregiving, and elder populations that also worked with a website developer to design a user-friendly website. This was achieved by making sure that: the site was not over-crowded with text; topics could be easily accessed; and that the site included photographs of Hispanic caregivers.

The website’s development was guided by the results obtained from a formative evaluation, which examined the extent to which the website had specific features that would increase its efficacy. These features were: 1) appeal – the extent to which the website captures users’ interest; 2) usability – the extent to which users were able to easily navigate the website; and 3) effective communication – the extent to which the website communicated content effectively so that users were able to receive education and support. Once the final version of the website was running, data were collected to assess the website’s effectiveness in increasing caregivers’ knowledge of ADRD, enhanced their self-efficacy for caregiving, enhanced their perceived social support, and reduced their perceived burden and emotional distress. Participants recruited for both the formative evaluation and effectiveness assessment received a monetary honorarium for their participation. Both protocols received approval from an Institutional Review Board.

Formative Evaluation

Participants

A purposive sample of twenty-three individuals (fourteen women and nine men) participated in the formative evaluation. They were recruited from an English as a Second Language class at a community-based organization in Boston, Massachusetts. All but one participant reported Spanish as their preferred language. Participants’ ages ranged from twenty-two to forty-seven. For this study, younger age was not an exclusion criterion since caregiving within Hispanic families tends to be multigenerational, thus involving young and older family members. After providing consent to participate in the study, participants spent approximately one hour navigating the website, and were then asked questions regarding the website’s appeal, usability, and communication features These questions were asked using a focus group format and the session was conducted in Spanish. Questions regarding appeal focused on the participant’s initial reactions to the site and their expectations about what it was without having a detailed explanation before hand. Questions on usability asked participants where they would click to read about a specific question or how they could find a specific feature (such as sound). Finally, questions regarding the communication features on the website focused on the cultural competency of the site and interactive features such as comments, questions, and social media.

Assessment of Website Effectiveness

The results of the formative evaluation were used to further refine the website’s content prior to assessing its effectiveness. A quasi-experimental two-group design with a one-month interval between the baseline and post-test measurements was used to accomplish this goal.

Participants

A purposive sample of seventy-two Spanish-speaking caregivers were recruited to assess the website’s effectiveness at increasing caregivers’ self-efficacy and perceived social support, as well as in decreasing caregiver burden and distress. Participants were recruited from Puerto Rico, Mexico, and Massachusetts. Participant ages ranged from forty-two to seventy-eight, with more than half being older than fifty-five years old. Most caregivers were full-time family caregivers, while some worked outside of the home as well. Participants had been caregivers between three and twenty years.

Participants from Puerto Rico and Massachusetts were recruited via outreach strategies that included: letters, press releases, flyers, as well as phone calls to agencies in contact with caregivers. In Mexico, participants were recruited from a pool of caregivers who received social support services at a neurology teaching hospital. While the number of participants from Puerto Rico and Mexico were roughly the same, recruitment challenges in Massachusetts only yielded five participants. Once potential participants agreed to join the study and signed an informed consent form, they were assigned to the control or intervention group. Participants received an honorarium after they completed each of the sessions.

Procedures

Participants were assigned to either an intervention or a control group. The intervention group went through four sessions of approximately one to one and a half hours each. The first intervention group session (pre-test session) was devoted to providing an overview of the study, familiarizing the caregiver with Cuidate Cuidador, and administering the pretest. The next two intervention group sessions were devoted to ensuring participants’ ability to use Cuidate Cuidador’s key features. Caregivers who were not computer-literate received specific assistance to navigate through the website’s key component features. The fourth session (post-test session) took place at the one-month point, and was devoted to the administration of the post-test evaluation, as well as a general debriefing for the study.

Participants assigned to the control group completed two sessions. A first session was devoted to providing an overview of the study, and administering the pre-test. Participants received printed Spanish-language educational materials on Alzheimer’s caregiving. The content covered in the the printed materials were similar to the topics offered in Cuidate Cuidador, but were obtained from other sources. Participants were instructed to take time between the pre-test and post-test to review and use the educational materials as a reference. The second session (post-test session) took place at a one-month follow-up, and was devoted to the administration of the post-test outcome measures, as well as a debriefing.

Measures

A set of outcome measures was employed to assess the impact of the website compared to the printed materials’ content on: (a) perceived mastery and competence in providing care as measured by the Personal Mastery Scale (PMS) (Pearlin & Schooler, 1978); (b) perceived social support measured by Lubben Social Network Scale (LSNS) (Lubben, 1988); (c) caregiver burden (Zarit, Reever, & Bach-Peterson, 1980); and (d) emotional distress, as measured by Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) (Radloff, 1977). These measures have all been validated for use with Spanish-speaking populations. In addition, participants were administered a twenty-item questionnaire to assess knowledge about ADRD and caregiving, which we developed specifically for this purpose. Participants’ experiences using the website were recorded using six open-ended questions which were asked during a focus group. Thus, we relied on both quantitative and qualitative data.

Results

Formative Evaluation

As noted, earlier participants were asked to provide input regarding the website’s appeal, usability, and communication features. Below are findings specific to these areas.

Appeal

Responses to questions about the appeal of the website were uniformly positive. The first attributes most participants noticed were the Spanish-language content and images depicting Hispanic caregivers. Eighty percent of participants reported that their initial thoughts on the website’s purpose were that it was to educate caregivers and families about ADRD. The topics considered most useful were the “Ten signs of Alzheimer’s disease” (sixteen percent) and “What can I do to take care of myself?” (twelve percent), as well as the “Ask an Expert” feature (twelve percent). The topic most participants reported that they would revisit was “What can I do to take care of myself?” (twenty-eight percent). Finally, sixty-four percent of participants responded that they would return to the website regularly to learn more about the disease.

Usability

When asked where they would click to get more information about a person with dementia having angry outbursts, fifty-two percent of respondents replied correctly. When asked where they would click to get more information about a person with dementia having trouble sleeping, fifty-six percent of respondents answered correctly. When asked where they would click to get more information about a person with dementia wandering, thirty-six percent answered correctly. Eighty-eight percent of participants were able to identify the speaker icon as a symbol for audio text. Fifty-two percent were able to find where they would click to change the font size. Regarding website ease of use, seventy-six percent of participants rated the site between an eight and a ten, on a scale from one to ten (one being hardest and ten being easiest).

Communication features

Responses to questions about the website’s communication features revealed that eighty-four percent of participants felt that the content was designed specifically for Hispanic users. Twenty percent of participants reported that the features Hispanics would like the most were the pictures and the testimonies and stories of other caregivers. They recommended that we add more of these. Thirty-six percent of participants suggested that we add links to other social media sites, such as Facebook.

Website’s Effectiveness

Quantitative data

Tables 1 and 2 summarize pre- and post-scores of the outcome measures described above by intervention versus control group status. In the PMS (Pearlin & Schooler, 1978) post-test, the intervention group proved to have a higher sense of self-mastery (M = 2.24, SD = .41) than the control group (M = 2.02, SD = .48). The difference was non-significant, t = −1.39, p > .05. The results of LSNS (Lubben, 1988) post-test showed that intervention group perceived a slightly greater sense of social support (M = 2.91, SD = .53), than the control group (M = 2.91, SD = .73). The difference was non-significant, t = −0.2, p > .05. The Caregiver Burden (Zarit, Reever, & Bach-Peterson, 1980) post-test results showed that caregivers in the intervention group (M = 1.73, SD = .81) felt a higher sense of burden than those in the control group (M = 1.66, SD = .62). The difference was non-significant, t = −2.93, p > .05. Finally, the results of the CES-D (Radloff, 1977) post-test showed that caregivers in the intervention had lower depressive symptomatology score (M = .76, SD = .60) than those in the control group (M = .78, SD = .50). The difference was non-significant, t = .09, p > .05. Although not statistically significant, findings suggest trends that exposure to information may be related to a higher sense of mastery (e.g., higher perceived self-efficacy for caregiving) and a reduction of depressive symptomatology. Lack of statistical significance may be due to the small sample size. In the twenty-item questionnaire to assess knowledge about ADRD, participants demonstrated moderate to high levels of knowledge about ADRD.

Table 1.

Pre-test scores by outcome measures and by condition

| Control (N = 23) | Intervention (N = 17) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | t | p | |

| PMS | 2.08 | .64 | 2.16 | .53 | −.47 | .64 |

| LSNS | 2.95 | 1.09 | 2.96 | .67 | −.01 | .99 |

| Burden | 1.78 | .63 | 1.64 | .61 | .68 | .5 |

| CES-D | .88 | .49 | .74 | .52 | .89 | .38 |

Table 2.

Post-test scores by outcome measures and by condition

| Control (N = 17) | Intervention (N = 15) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | t | p | |

| PMS | 2.02 | .48 | 2.24 | .41 | −1.39 | .17 |

| LSNS | 2.91 | .73 | 2.91 | .53 | −.24 | .981 |

| Burden | 1.66 | .62 | 1.73 | .81 | −2.93 | .771 |

| CES-D | .78 | .50 | .76 | .60 | .09 | .933 |

Qualitative data

As noted earlier, participants were asked six open-ended questions about their experiences using the website. These questions were asked using a focus group format. After the focus groups, the facilitators reviewed their notes and prepared a summary of participants’ comments. The questions covered the following topics: 1) number of times visiting the website; 2) usage and impressions of the audio feature; 3) usage of the comments feature; 4) experiences with the “Ask an expert” section; 4) impressions of questions answered by experts; 5) additional comments and experiences regarding the website. A brief discussion of participants’ answers is offered below.

The vast majority of the participants visited the website at least three times, whereas others reported visiting the site at least ten times or every other day. The average visit time lasted between thirty minutes and an hour. Many participants posted comments on the site and sent questions to the experts, and some who didn’t indicated that they could not find the particular feature or did not know how to do it. Two participants submitted questions to the experts and reported receiving prompt and satisfactory answers. They were very pleased with the “Ask an Expert” feature “because other websites do not have that feature, and it is necessary.” Most participants indicated that the website is an excellent tool for caregivers. They deemed it “comprehensive” and “easy-to-use”. They found the website to be very practical and helpful in their daily lives:

“Marta’s story is very similar to my mother’s when it comes to her husband’s behavior. I think this is very normal in this type of patient. The important thing is to identify the situation and seek help, like she did.” (Sent to the Cuidate Cuidador website e-mail and translated into English.)

They also reported that the information provided was beneficial, that it was written in clear, simple language, and that they would recommend the printed materials as well as the website to others. Some participants found that most of the information was more relevant to caregivers dealing with a patient at the earlier stages of the disease. Regarding the audio component, some participants experienced difficulties using it, while others found it useful, but preferred to read the information in order to save time. Most participants preferred to read, rather than use the audio component. One participant reported using it because “it was easier listening to the information while doing other things.” Participants also pointed out that since many of their responsibilities as main caregivers prevented them from leaving the home, the website was an invaluable resource that they could conveniently consult for information or support:

“I think talking and writing about what we think helps us blow off some steam. This is all very interesting and some of the topics really help us better understand our patient’s disease.” (Sent to the Cuidate Cuidador website e-mail and translated into English).

Many participants reported recommending the site to other caregivers and encouraging others to promote it. They made recommendations to improve the website such as: 1) adding a section on spirituality; 2) providing more detailed information on specific topics; 3) adding dementia specialist physicians to the “Ask an Expert” section; 4) adding information about local resources; and 5) adding information about medication therapies.

“I would like to learn more about techniques or responses that won’t cause anxiety that I can use when a person says they don’t remember a particular person or name. How do you know when a person really doesn’t remember or pretending not to?” Sent to the Cuidate Cuidador website e-mail and translated into English.

Visits to website during evaluation period

Website visits represent a common form of evaluation for determining website popularity. Using web analytics, unique visitors, overall visits, origins (source from where an individual connects to the site), and location, our users were tracked. Statistics on the Cuidate Cuidador website document how visits more than doubled over the one month study period (see Table 3). The number of unique visitors also increased, though not at the same rate as visits. These data provide evidence that visitors were entering the site repeatedly. The number of pages visited was also at a much higher rate than the number of visitors, showing that people were navigating through various pages of the site. Statistics indicate that the majority of website visitors were from the U.S., Mexico, and Puerto Rico (see Table 4).

Table 3.

Website Visits Data from Cuidate Cuidador

| Months | Unique Visitors | Pages Visited by Unique Visitors | Pages Visited by All Visitors |

|---|---|---|---|

| January 2010 | 53 | 93 | 2,431 |

| February 2010 | 118 | 190 | 1,668 |

| March 2010 | 174 | 422 | 4,705 |

Table 4.

Top Country of Users Visiting Cuidate Cuidador

| Countries | Pages |

|---|---|

| United States | 5,537 |

| Mexico | 2,168 |

| Puerto Rico | 818 |

Cuidate Cuidador in social media

Maintaining a Spanish-language website presents a unique challenge, as there are many Spanish-speaking countries whose population we want to reach, but for one reason or another may not have easy access to our site, mainly due to barriers with international search engines. The constant creation of new content to keep users coming back to the website can also be a challenge, which was successfully addressed by encouraging user-generated content. Additionally, participants from both the formative and the assessment of the website’s effectiveness recommended linking Cuidate Cuidador to other sites, such as Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube. All of these recommendations led to the creation of social media pages, where people could more easily and actively engage and create content, which expanded the components of the Cuidate Cuidador website (see Table 5). One of the advantages of using Twitter and Facebook platforms was the ability to maintain a worldwide presence, and have features that allow for real-time communication between community facilitators and visitors.

Table 5.

Cuidate Cuidador Social Media Visitors as of June 26th, 2012

| Facebook Likes | 2,055 |

| Twitter Followers | 188 |

| Youtube ChannelViews | 13, 318 |

Once Cuidate Cuidador was established on Facebook, various strategies were used to reach out to caregivers and organizations that were already registered on the site. Searches were made for particular organizations, such as different branches of Alzheimer’s Association, as well as for individuals who had listed particular interests, such as “caregiving” or “Alzheimer’s”. By purchasing ad space on Facebook, we were also able to place ads, and re-direct those who clicked on them either back to the Facebook page or website.

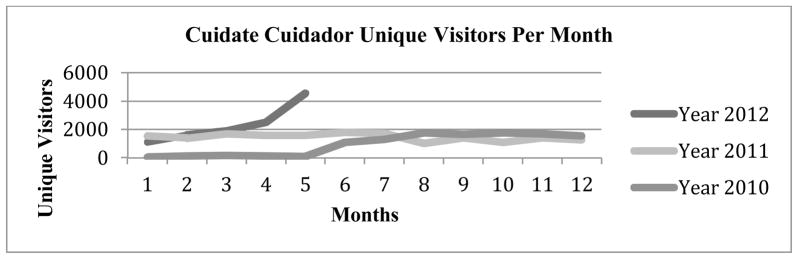

Social media sites require certain demographic information from users when they sign-in to the site. This information is available (in aggregate, not at the individual level) when the user begins to follow Cuidate Cuidador. This information (mainly user’s location, age, and gender) is used to get a better sense of who is utilizing the website and what content they are accessing, to better optimize content for users. Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube engage users on their platforms and then drive visitors to the main site, therefore becoming primary sources of traffic to the website and increasing the number of unique visitors to the site (see Figure 1 and Table 6). The popularity of the website and the social media sites can be viewed through the site analytics as presented above, as well as through the hundreds of messages that have been received, such as:

“Thank you for inviting me. The truth is I’m not alone. I know I can count on you and that every day I learn more. I feel calm, confident, and strong in the front of this new challenge life has given me. God bless you and keep illuminating you, so that you can give us more tools. Thank you.” Sent to the Cuidate Cuidador website e-mail and translated into English.

Figure 1.

Cuidate Cuidador Unique Visitors up to May 2012

Table 6.

Cuidate Cuidador Facebook Visitors as of July 1st, 2012 by Gender and Age

| F.13-17 | F.18-24 | F.25-34 | F.35-44 | F.45-54 | F.55-64 | F.65+ | M.13-17 | M.18-24 | M.25-34 | M.35-44 | M.45-54 | M.55-64 | M.65+ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.2% | 7.6% | 20.4% | 22.9% | 20.9% | 6.7% | 2.2% | 0.4% | 2.1% | 4.1% | 4.9% | 4.1% | 2.0% | 0.4% |

Discussion

Few intervention studies have been conducted with Hispanic caregivers of older adults with dementia (Llanque & Enriquez, 2012), even though previous research has shown that Hispanic caregivers could greatly benefit from receiving training in caregiving activities, information about services for caregivers and patients, and Spanish-language, culturally sensitive materials (NAC and Evercare, 2008). The creation of Cuidate Cuidador contributed to the field by offering a new, consumer-friendly, bilingual and technologically appealing vehicle for Hispanic caregivers. Results demonstrate the promise of this approach for enhancing the skills of caregivers of dementia patients and reducing of caregivers’ depressive symptomatology. Although the use of technology with Hispanic caregivers has already proven to be promising (Czaja & Rubert, 2002; Eisdorfer et al., 2003), the findings specific to the use of social media platforms with this population are a novel contribution to the caregiving literature.

Overall results from the formative evaluation showed that the website was easy to navigate and user-friendly. Most participants suggested it to be a valuable resource for Hispanic caregivers and would recommend it to others. The quantitative findings related to the assessment of the website’s effectiveness showed that, despite a small sample size, exposure to information through Cuidate Cuidador might be related to a higher perceived self-efficacy for caregiving and less isolation. Users’ comments reaffirmed the importance and usability of the website.

In addition to the main website, the use of social media sites continues to lead to better content and more interaction with users and provides an easy way for users to be notified about new content, such as with Facebook notifications or Tweets. These social networks promote a sense of community with their participants during their interactions. Those who follow these sites may participate in any way they feel comfortable, from reading posted articles, to writing their responses, or even suggesting new topics they would like to see covered in more detail. Users are encouraged to actively engage in the community by sending personal stories of their experiences, pictures, or writing articles about caregiving – all of which increase their sense of connectivity. The social media component provided many caregivers the opportunity to join a virtual community with other caregivers, something they had not been able to do locally because of either the absence of support groups in their area, lack of time, or inability to leave the home.

The study had two main limitations. The expected sample was to have fifty participants in the intervention group and fifty participants in the control group. As a result of problems with recruitment, we had fewer participants than we intended. The second limitation was not having the control group come for in-between sessions, as the intervention group received. The drawback is that participants in the control group did not receive the same level of attention as the intervention group, allowing speculation for what caused the differences in the results.

Conclusions

Hispanic caregivers face particular challenges that require consideration and innovative practices in order to address them. This project was based on trends of computer use and results of previous studies that had shown technology to be effective in addressing dementia caregivers’ well-being. Cuidate Cuidador provided an opportunity to explore the feasibility of a communication and social support model for bridging the conventional face-to-face support community and an online community. Our results show that our findings were not statistically significant, which could be due to a small sample size. Further research projects should pursue a larger number of subjects to better examine the effectiveness of online communities. Despite lack of statistically significant findings, our results offer a more fine-grained understanding of the needs of Hispanic caregivers, and how these can be addressed in the field of e-health. The use of social media technology can provide support to caregivers in a variety of ways: improving knowledge and skills, reducing isolation, linking caregivers with each other, and with other resources needed for caregiving. However, in order to maintain the functionality of the website, a team of support staff is necessary. Dementia experts need to be available to answer caregivers’ questions within a one to two day time frame. A web designer and management team need to be available in case, for example, the website has a technical glitch. Further, a team needs to be available to manage e-mail, and other user-generated content. In addition to the support staff mentioned above, content creators are needed for the website to stay fresh and relevant. Content creators not only ensure that the content on the website remains current, they search for new content, and make daily postings on the various social media sites, interact with users, and help re-direct them to the main site, depending on their caregiving needs. The resources to maintain a team dedicated to the upkeep of the website is a major challenge with this type of technological tool.

It is important to think locally, as well as internationally, regarding the design of online interventions. Although content and communities can cross geographical borders, it is essential to provide caregivers with resources that are local to their own cities, and can therefore offer even more tailored assistance to fit their needs. While Cuidate Cuidador attempted to do that by offering contact information for local resources, future interventions should concentrate on further bridging online and local resources. While e-health and e-technologies are increasing, there will always be individual caregivers who prefer the more traditional types of resources (for example pamphlets and other printed materials, as well as in-person trainings) to meet their caregiving needs. Thus, e-health programs for this population should strive to offer materials that can be reproduced and used by organizations that provide traditional services, in order to ensure that they have culturally competent and expert material that they can use at little to no cost.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This research was funded by National Institute on Aging Small Business Innovation Research grants (SBIRs) (R43 and R44AG020869) to Environment and Health Group, Inc.

Contributor Information

Marta E. Pagán-Ortiz, Environment & Health Group, Inc., Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA

Dharma E. Cortés, Environment & Health Group, Inc., Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA

Noelle Rudloff, Environment & Health Group, Inc., Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA.

Patricia Weitzman, Environment & Health Group, Inc., Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA.

Sue Levkoff, Environment & Health Group, Inc., Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA and College of Social Work, University of South Carolina, Columbia, South Carolina, USA.

References

- Acton GJ. Health-promoting self-care in family caregivers. Western Journal of Nursing Research. 2002;24(1):73–86. doi: 10.1177/01939450222045716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexy EM. Computers and caregiving: reaching out and redesigning interventions for homebound older adults and caregivers. Holistic Nursing Practice. 2000;14(4):60–66. doi: 10.1097/00004650-200007000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biegel D, Sales E, Schulz R. Family caregiving in chronic illness. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Box TL, White H, McConnell A, Clip E, Branch LG, Sloane R, Piepper C. A randomized controlled trial of the psychosocial impact of providing internet training and access to older adults. Aging & Mental Health. 2002;6(3):213–221. doi: 10.1080/13607860220142422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox C, Monk A. Strain among caregivers: Comparing the 34 experiences of African American and Hispanic caregivers of Alzheimer’s relatives. The International Journal of Aging and Human Development. 1996;43(2):93–105. doi: 10.2190/DYQ1-TPRP-VHTC-38VU. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czaja SJ, Rubert MP. Telecommunications technology as an aid to family caregivers of persons with dementia. Psychosomatic Medicine: Journal of Biobehavioral Medicine. 2002;64(3):469–476. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200205000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisdorfer C, Czaja SJ, Loewenstein DA, Rubert MP, Argüelles S, Mitrani VB, Szapocznic J. The effect of a family therapy and technology-based intervention on caregiver depression. The Gerontologist. 2003;43(4):521–531. doi: 10.1093/geront/43.4.521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Etters L, Goodall D, Harrison BE. Caregiver burden among dementia patient caregivers: A review of the literature. Journal of the American Academy of Nurse Practitioners. 2008;20(8):423–428. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7599.2008.00342.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Federal Interagency Forum on Aging Statistics. Older Americans 2010: Key indicators of well-being. 2010 Retrieved on May 15, 2012 from: http://www.agingstats.gov/agingstatsdotnet/Main_Site/Data/2010_Documents/Docs/OA_2010.pdf.

- Kane MN. Ethnoculturally-sensitive practice and Alzheimer’s disease. American Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease. 2000;15:80–86. [Google Scholar]

- Karlawish J, Barg FK, Augsburger D, Beaver J, Ferguson A, Nunez J. What Latino Puerto Ricans and non-Latinos say when they talk about Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s and Dementia: The Journal of the Alzheimer’s Association. 2011;7(2):161–170. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2010.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levkoff S, Levy B, Weitzman PF. The role of ethnicity and religion in the help seeking of family caregivers to dementia-affected elders. Journal of Cross-Cultural Gerontology. 1999;14:335–356. doi: 10.1023/a:1006655217810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livingston G. Latinos and Digital Technology, 2010. Washington D.C: Pew Hispanic Center; Feb 9, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Llanque SM, Enriquez M. Interventions for Hispanic caregivers of patients with dementia: A review of the literature. American Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease & Other Dementias. 2012;27(1):23–32. doi: 10.1177/1533317512439794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lubben JE. Assessing social networks among elderly populations. Family & Community Health. 1988;11(3):42–52. [Google Scholar]

- Mahoney R, Regan C, Katona C, Livingston G. Anxiety and depression in family caregivers of people with Alzheimer disease. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2005;13(9):795–801. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajgp.13.9.795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McConatha D, McConatha JT, Dermigny R. The use of interactive computer services to enhance the quality of life for long-term care residents. The Gerontologist. 1994;34(4):553–6. doi: 10.1093/geront/34.4.553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Alliance for Caregiving [NAC] and Evercare. Study of Hispanic family caregiving in the US: Findings from a national study. 2008 Retrieved on June 1, 2012 from: http://www.caregiving.org/data/Hispanic_Caregiver_Study_web_ENG_FINAL_11_04_08.pdf.

- National Institute on Aging [NIA] Alzheimer’s disease fact sheet. 2012 Jun; Retrieved on June 27, 2012 from: http://www.nia.nih.gov/alzheimers/publication/alzheimers-disease-fact-sheet.

- Neal L. Everything in Moderation: The Key to Using Text Chat Is a Knowledgeable Moderator. ACM eLearn Magazine. 2005 Retrieved on June 25, 2012 from: http://elearnmag.acm.org/archive.cfm?aid=1082213.

- Papastavrou E, Kalokerinou A, Papacostas SS, Tsangari H, Sourtzi P. Caring for a relative with dementia: Family caregiver burden. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2007;58(5):446–457. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04250.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearlin LI, Aneshensel CS, Mullan JT, Whitlach CJ. Caregiving and its social support. In: Binstock RH, George LK, editors. Handbook of aging and the social sciences. 4. San Diego, CA: Academic; 1997. pp. 283–302. [Google Scholar]

- Pinquart M, Sörensen S. Ethnic differences in stressors, resources, and psychological outcomes of family caregiving: a meta-analysis. The Gerontologist. 2005;45(1):90–106. doi: 10.1093/geront/45.1.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1(3):385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Reynoso-Vallejo H, Henderson N, Levkoff SE. Dementia radio support group for caregivers in the Latino community. The Gerontologist. 1998;38 [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal Gelman C. “La lucha”: The experience of Latino family caregivers of patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Clinical Gerontologist. 2010;33(3):181–193. [Google Scholar]

- Sum S, Mathews RM, Pourghasem M, Hughes I. Internet use as a predictor of sense of community in older people. Cyberpsychology & Behavior. 2009;12(2):235–239. doi: 10.1089/cpb.2008.0150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talamantes MA, Aranda MP. Cultural Competency in Working with Latino Family Caregivers. Family Caregiver Alliance. 2004 Mar; Retrieved on June 15, 2012 from: http://www.caregiver.org/caregiver/jsp/content_node.jsp?nodeid1/41095.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. National Alzheimer’s Project Act. 2012 Jun; Retrieved on June 23, 2012 from: http://aspe.hhs.gov/daltcp/napa/

- Valle R. Culture-fair behavioral symptom differential assessment and intervention in dementing illness. Alzheimer Disease & Associated Disorders. 1994;8(3):21–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valle R, Yamada AM, Barrio D. Ethnic differences in social network help- seeking strategies among Latino and Euro-American dementia caregivers. Aging & Mental Health. 2004;8(6):535–543. doi: 10.1080/13607860410001725045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weitzman P, Neal L, Chen H, Levkoff SE. Designing a culturally attuned bilingual education website for US Latino dementia caregivers. Ageing International. 2008;32:15–24. [Google Scholar]

- Willette-Murphy M, Todero C, Yeaworth R. Mental health and sleep of older wife caregivers for spouses with Alzheimer’s disease and related disorders. Issues in Mental Health Nursing. 2006;27:837–852. doi: 10.1080/01612840600840711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White H, McConnell E, Clipp E, Branch LG, Sloane R, Pieper C, Box TL. A randomized controlled trial of the psychosocial impact of providing Internet training and access to older adults. Aging & Mental Health. 2002;6(3):213–221. doi: 10.1080/13607860220142422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeo G, Gallagher-Thompson D. Ethnicity and the Dementias. Washington D.C: Taylor & Francis; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Zarit SH, Reever KE, Bach-Peterson J. Relatives of the impaired elderly: Correlates of feelings of burden. The Gerontologist. 1980;20:649–655. doi: 10.1093/geront/20.6.649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]