Abstract

Kalirin, a Rho GDP/GTP exchange factor for Rac1 and RhoG, is known to play an essential role in the formation and maintenance of excitatory synapses and in the secretion of neuropeptides.

Mice unable to express any of the isoforms of Kalrn in cells that produce POMC at any time during development (POMC cells) exhibited reduced anxiety-like behavior and reduced acquisition of passive avoidance behavior, along with sex-specific alteration in the corticosterone response to restraint stress. Strikingly, lack of Kalrn expression in POMC cells closely mimicked the effects of global Kalrn knockout on anxiety-like behavior and passive avoidance conditioning without causing the other deficits noted in Kalrn knockout mice. Our data suggest that deficits in excitatory inputs onto POMC neurons are responsible for the behavioral phenotypes observed.

Keywords: pituitary, ACTH, corticosterone, passive-avoidance, Cre-recombinase

INTRODUCTION

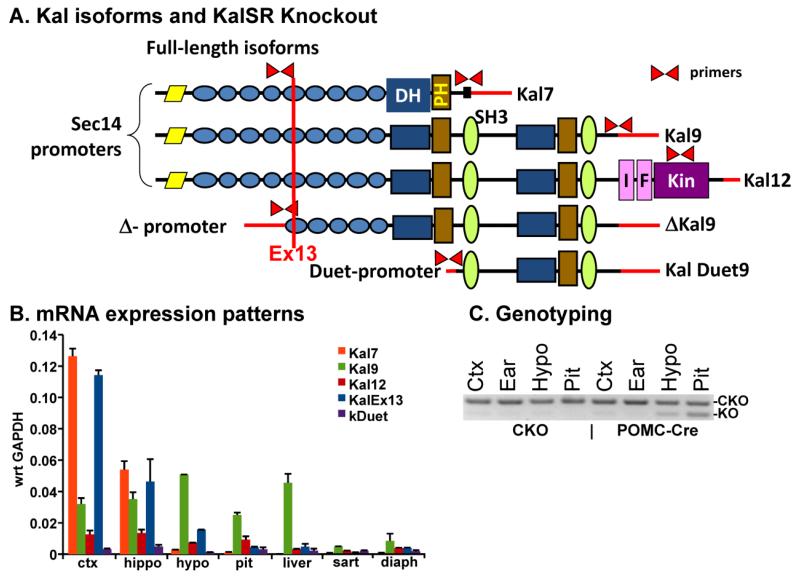

The human KALRN gene encompasses several functional domains and generates multiple isoforms (Fig.1A); KALRN has been implicated in cardiovascular disease, ischemic stroke, schizophrenia, Alzheimer’s disease and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (Beresewicz et al. 2008;Krug et al. 2010;Kushima et al. 2012;Wang et al. 2007;Wu et al. 2012;Youn et al. 2007). The rodent Kalrn gene gives rise to similar developmentally regulated and functionally distinct isoforms that were named based on the lengths of their mRNAs (Johnson et al. 2000;McPherson et al. 2004;Penzes et al. 2011). Kalirin-7 (Kal7) expression is limited to neurons, whereas Kal9 and Kal12 are broadly expressed (Ma et al. 2008;Mandela et al. 2012;Penzes et al. 2001;Penzes et al. 2001;Wu et al. 2012). Kal12, the largest isoform, includes a lipid binding Sec14 domain, nine spectrin repeats, two guanine nucleotide exchange factor (GEF) domains, two SH3 domains, an Ig/FnIII domain and a putative kinase domain (Mandela and Ma 2012;Miller et al. 2013;Rabiner et al. 2005); Kal7 includes a PDZ binding motif and is localized to the post-synaptic density.

Fig. 1. Kalirin isoforms and the Kalirin POMC-Cre mouse.

A] The major isoforms of Kalirin are indicated, along with the position of the Exon 13 ablation. The black box at the COOH-terminus of Kal7 is a PDZ-binding motif. B] Real time polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) was performed on RNA from the indicated tissues as described (Mandela et al. 2012). Results are expressed with respect to the GAPDH signal in the same samples on the same 96-well plate. C] Genotyping from the tissues indicated was performed as described; the products expected from KalSRCKO and KalSRKO mice are indicated (Mandela et al. 2012).

Kalirin was first identified as an interactor with the cytosolic domain of Peptidylglycine α-Amidating Monooxygenase (PAM), an enzyme essential for the synthesis of many bioactive peptides (Alam et al. 1996). The spectrin repeats common to the full-length isoforms of Kalirin are responsible for its ability to interact with PAM and for the formation of Kalirin/iNOS heterodimers (Ratovitski et al. 1999). In extracts of hippocampi from Alzheimer disease patients, there is a paucity of Kal7 and an excess of iNOS (Nathan et al. 2005;Youn et al. 2007;Youn et al. 2007). Although early studies demonstrated a role for Kalirin in controlling peptide hormone secretion, subsequent investigations focused on the role of Kal7 in dendritic spine formation and function. Roles for the larger isoforms of Kalirin in the cardiovascular, skeletal and neuromuscular systems have subsequently been demonstrated (Huang et al. 2013;Mandela et al. 2012;Wu et al. 2012).

Mice globally lacking the exon encoding the PDZ binding motif unique to Kal7 (Kal7KO mice) exhibit decreased anxiety-like behavior and decreased acquisition of passive avoidance behavior (Ma et al. 2008). In order to ablate all of the major isoforms of Kalirin, exon 13, which encodes part of the spectrin repeat region, was flanked by lox-p sites, generating KalSRKO mice (Mandela et al. 2012;Wu et al. 2012). In addition to the deficits observed in Kal7KO mice, the growth curves for male and female global Kalirin knockout mice (KalSRKO) are delayed, and female KalSRKO mice have difficulty with parturition and lactation. Primary pituitary cultures prepared from KalSRKO mice exhibit increased basal secretion of growth hormone and prolactin (Mandela et al. 2012).

Given the crucial role of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis in the response to stress (Bhargava et al. 2000;Young et al. 1990), and the deficiencies in the stress responses seen with global Kalrn knockout mice (Mandela et al. 2012), we wanted to test the consequences of eliminating Kalirin expression only in POMC cells (KalPOMC-KO). Studies on the role of individual neuropeptides in C. elegans have revealed their ability to modulate the circuitry involved in adjusting behavioral responses to environmental inputs (Bargmann 2012). Mice of the desired genotype were generated by breeding global Kalirin conditional knockout mice (KalSRCKO/CKO) to mice expressing Cre-recombinase under the control of the POMC promoter (Balthasar et al. 2004). Cells which express POMC at any time during development are referred to as POMC cells; although they may not produce POMC in the adult, expression of POMC and Cre-recombinase during development means that Kalirin expression will have been eliminated in these cells. POMC cells that actually express POMC in the adult are referred to as POMC-producing cells. The major sites of POMC production in the adult include anterior pituitary corticotropes, intermediate pituitary melanotropes and POMC neurons in the arcuate nucleus of the hypothalamus and nucleus of the tractus solitarius (NTS) (Eipper and Mains 1980;Khachaturian et al. 1985). The anterior pituitary POMC product, adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), stimulates glucocorticoid production and secretion by the adrenal cortex; glucocorticoid receptors are found in many neurons and mediate the multiple effects of stress on nervous system function (Bhargava et al. 2000;Dallman et al. 1987;Young et al. 1990). POMC-producing neurons synthesize non-acetylated ACTH(1-13)NH2 (Emeson and Eipper 1986), which signals satiety (Ellacott and Cone 2006), and β-endorphin, a potent endogenous opiate (Khachaturian et al. 1985). Behavioral and biochemical approaches were used to test the hypothesis that a lack of Kalirin expression in POMC cells contributes to a subset of the behavioral alterations observed in KalSRKO mice.

METHODS

In order to eliminate both the full-length and Δ-isoforms of Kalirin, lox-p sites were inserted both before and after Kalirin Exon 13 (Fig.1A), which is 3′ to the Δ-isoform initiation site in the intron preceding Exon 11 (Mandela et al. 2012). The KalSRCKO/CKO mice thus created were of normal weight, reproduced well and had an unaltered distribution and level of Kalirin isoforms. The floxed allele has been bred more than 15 generations into the C57Bl/6 background. Knockout of Kalirin in POMC neurons and endocrine cells was accomplished by mating KalSRCKO/CKO mice to POMC-Cre mouse lines that target expression of Cre-recombinase using the POMC promoter (JAX #5965). The pups were genotyped for the presence of both lox-p and Cre (Mandela et al. 2012). Mice were designated as Kalirin knockouts in POMC cells (KalSRPOMC-KO) when they expressed Cre-recombinase and were homozygous for the floxed Kalirin allele (KalSRCKO/CKO). KalSRCKO/CKO mice (KalSRCKO) were used as controls for KalSRPOMC-KO mice; these mice were identical to wild type mice in all behavioral and biochemical tests done so far (Mandela et al. 2012).

POMC Cre-recombinase Specificity

Homozygous Rosa26-LacZ mice (R26R; JAX# 3474; B6.129S4-Gt(ROSA)26Sortm1Sor/J) were bred with the POMC-Cre mice from JAX. The offspring whose genomes contained both the Cre and β-galactosidase coding sequences were used to localize the sites of Cre-recombinase expression with X-gal staining. Adult mice were sacrificed, pituitaries and brains were collected, and frozen sections were prepared and stained with X-Gal for lacZ (β-galactosidase) activity. Because the pattern of expression of Cre in the POMC-Cre mice has been a matter of controversy (Balthasar et al. 2004;King and Hentges 2011;Morrison and Munzberg 2012;Padilla et al. 2010;Padilla et al. 2012), the POMC-Cre mice were also bred with homozygous Rosa26-TdTomato mice (JAX# 7905; B6.129S6-Gt(ROSA)26Sortm9(CAG-tdTomato)Hze/J) and the pattern of TdTomato fluorescence was examined.

β-galactosidase and TdTomato Visualization

Animals were perfused, fixed and sectioned as previously described (Mandela et al. 2012). β-galactosidase was visualized in coronal sections using X-Gal staining (Soriano 1999). TdTomato fluorescence was observed directly and nuclei were identified using the Hoechst stain. The identity of the TdTomato-positive neurons was further probed using immunocytochemistry for Vglut1 (1:3000, Chemicon, AB5905), GAD65/67 (1:2000, Sigma, G5163), Neuropeptide Y (JH4 [1:20,000]), and several products of POMC cleavage (Georgie [1:4000], 16K fragment; affinity-purified JH189 [1:500], γ3MSH; JH44 [1:4000] and Kathy [1:4000], CLIP; JH93 [1:1000], N-ACTH) (Gaier et al. 2013;Khachaturian et al. 1985;Ma et al. 2002).

Behavioral Studies

Animals were group housed in the University of Connecticut Health Center (UCHC) animal facility with a 12 h light/dark cycle (lights on 7:00 A.M. to 7:00 P.M.). For behavioral studies, male and female littermates between 2 and 4 months of age were tested during the light phase. All animals were handled daily for at least 4 d before behavioral testing to minimize experimenter-induced stress during testing. For all experiments, animals were allowed to habituate to the room for 1 h before testing. All animals were reused for behavioral tests, but care was taken to ensure that the less stressful tests preceded those that were more stressful (elevated zero maze→ open field locomotion→ tail suspension test → prepulse inhibition of acoustic startle → rotarod→ object recognition test→ passive avoidance test → restraint stress). Tests were separated by 2 or more days, and the same set of mice were used for all behavioral experiments. Open field, elevated zero maze, passive avoidance, and object recognition tests were performed as described (Ma et al. 2008), as were rotarod, prepulse inhibition and restraint stress (Mandela et al. 2012). Core body temperature was measured with a rectal probe at regular intervals, 1 h before placement at 4° C and after 40, 80, and 120 min of exposure to 4° C (Bousquet-Moore et al. 2010). For studies where males and females did not differ (novel object recognition, prepulse inhibition, open field, rotarod), data were pooled, as is frequent in behavioral studies (Bousquet-Moore et al. 2010;Chen et al. 2008;Haller et al. 2002;Pillai-Nair et al. 2005;Pogorelov et al. 2005).

Tail suspension

Mice were suspended 70 cm above the floor of the cage for 6 min by taping the tail to a coat hanger (Steru et al. 1985). Mice were videotaped and total time spent immobile (defined as the complete cessation of movement) was scored. Males (N=11 KalSRCKO, N=11 KalSRPOMC-KO) and Females (N=6, 6) were tested separately.

Blood Corticosterone Levels

Blood samples were taken at least one week after the last behavioral testing; all samples were taken in mid-morning, 24h or more before the restraint stress. Corticosterone was measured with a radioimmunoassay from MP Diagnostics (Santa Ana, CA, USA). The basal serum corticosterone values obtained (50 ng/ml) were in good agreement with literature values for basal corticosterone levels in mice (Bousquet-Moore et al. 2009), indicating that the mice were given adequate time to return to baseline after any earlier behavioral tests; the detection limit of the assay was 6 ng/ml, eight-fold below the basal corticosterone levels. In Experiment 1, we utilized a 15 min restraint period; in Experiment 2, which included half as many animals in each group, we used a 30 min restraint period. The restraint period was varied to determine whether corticosterone values had reached a plateau with the longer stress. All samples were assayed in duplicate and averaged for each animal; the intrasample variation (variation between duplicate samples) was ± 30% and the between-assay variation for the low and high control samples included in the kit was <12%.

Pituitary Cell Culture

Anterior pituitaries from adult male and female mice were separated from the neurointermediate lobes under a dissecting microscope, and subjected to sequential collagenase and trypsin digestion at 32–37°C (Mandela et al. 2012). Dissociated cells were plated into wells of a 96 well plate for secretion experiments (1.5 pituitaries/well in different experiments). Cells were fed with Complete Serum-free Medium (CSFM, Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium/F-12, 25 mM HEPES, 100 units/ml penicillin, 100 mg/ml streptomycin, insulin/transferrin/selenium [Invitrogen], and 1 mg/ml fatty acid-free bovine serum albumin [Sigma]) until used (Mandela et al. 2012).

Secretion Stimulation Paradigm

Primary cells that had been maintained in culture for 3 days were pre-rinsed 2–3 times (15–30 min each) with serum-free DMEM air medium (bicarbonate eliminated and replaced with HEPES, containing 0.1 mg/ml BSA) devoid of secretagogue (Mandela et al. 2012). Cells were then fed with air medium alone (control) or air medium containing secretagogue (stimulation): 20 nM CRH and/or 20 nM arginine vasopressin (AVP) (Phoenix Pharmaceuticals, Burlingame CA), 2 mM BaCl2 or 1 μM phorbol myristate acetate. Basal or stimulated secretion was assessed over a 30 min time period; spent medium was collected and centrifuged to remove any non–adherent cells. The ACTH content in the spent medium was analyzed in duplicate using an ELISA kit (EIA-3647; DRG International, NJ, USA) with a sensitivity of 0.46 pg/ml and intra-assay variation of <10%.

Quantitative (real-time) Polymerase Chain Reaction

RNA was prepared and Q-PCR was performed as described (Mandela et al. 2012) using Kalirin primers as listed. In addition, a pair of primers for the 5′ sequence unique to mouse Duet [Genbank AK088732.1] was used (120 nt product):

TTCGTGCCATGCCGGAGCACTG Tm 60C

CTACAAGGGAAGCAACAGCAGCACTTAG Tm 61C

Statistical Analyses

SigmaPlot 11 was used for analyses (Pairwise Multiple Comparison Procedures [Holm-Sidak method]; 2-way ANOVA; RMANOVA, as appropriate) within a treatment, across genotype, and across sex. Details are provided in the figure legends. For all comparisons with statistically significant differences, alpha=0.05, and data are expressed as mean ± SEM. Calculations of η2 were performed according to http://www.uccs.edu/lbecker/glm_effectsize.html using the SigmaPlot11 output.

RESULTS

Kalirin Isoforms in POMC-Producing Tissues

Since POMC is most highly expressed in the adult in the intermediate and anterior lobes of the pituitary and in the arcuate nucleus of the hypothalamus (Balthasar et al. 2004;Eipper and Mains 1980), we used quantitative PCR (Q-PCR) to compare the expression of Kalirin isoforms in these tissues to the expression pattern in cortex and hippocampus (Fig.1B). We looked first at usage of the different Kalrn 3′-terminal exons; although the Kal7-specific exon was the most abundant 3′-terminal exon used in cortex and hippocampus, as expected, it was not highly expressed in the hypothalamus and was barely detectable in the other tissues tested. The Kal9-specific 3′-terminal exon was more prevalent than the Kal7- or Kal12-specific 3′-terminal exon in the hypothalamus, pituitary and liver. Transcripts encoding full-length isoforms of Kalirin are initiated at one of the four Sec14 promoters (Mains et al. 2011) and yield transcripts that include Exon13; full-length transcripts (KalEx13) predominated in cortex and hippocampus, but were less prevalent in hypothalamus, pituitary and liver; transcripts initiated from the Duet promoter were minor players in all tissues (Kawai et al. 1999). Taken together, in both hypothalamus and pituitary, ΔKal9 is expected to be the major Kalirin isoform.

To assess the contribution of POMC cells to the deficits observed in Kalirin knockout mice, we chose to mate mice in which Kalrn Exon13 was flanked by lox-p sites (KalSRCKO) (Mandela et al. 2012) to mice expressing Cre-recombinase under control of the POMC promoter, yielding KalSRPOMC-KO mice. The pattern of ablation of Kalirin Exon 13 was first determined by PCR genotype analysis in tissues known to express POMC at high levels in the adult (Fig.1C). Excision of Kalirin Exon13 was readily apparent in the pituitary and in the hypothalamus of KalSRPOMC-KO mice, where POMC is expressed in a significant minority of the cells; as expected, excision of Kal Exon13 was not detectable in DNA prepared from cortex or ear clips of KalSRPOMC-KO mice.

Sites of Kal Exon 13 Excision

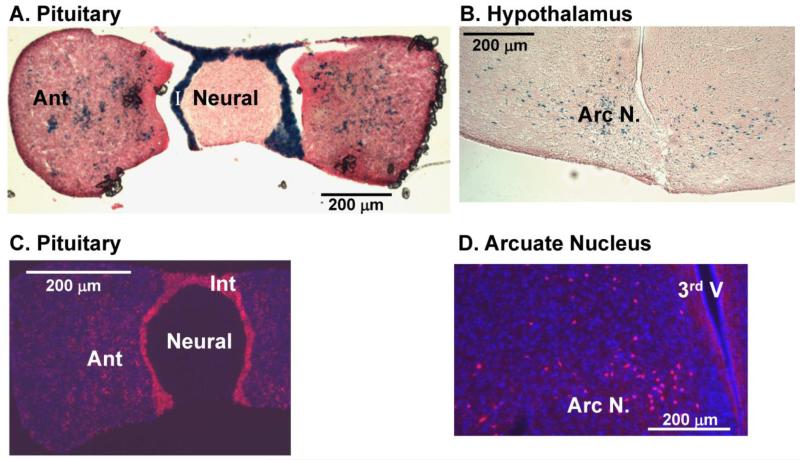

Since there has been considerable controversy about the pattern of expression of Cre-recombinase in POMC-Cre mice (Balthasar et al. 2004;King and Hentges 2011;Morrison and Munzberg 2012;Padilla et al. 2010;Padilla et al. 2012), we used two Rosa reporter lines to explore this issue in the mice used for these studies. Using the Rosa26-LacZ mouse, β-galactosidase expression was observed in scattered cells throughout the anterior pituitary and in all of the cells in the intermediate pituitary; corticotropes constitute about 5-10% of the cells in the anterior lobe while melanotropes are the only endocrine cells in the intermediate lobe (Fig.2A). As expected, scattered neurons in the arcuate nucleus also expressed β-galactosidase (Fig.2B).

Fig. 2. The POMC promoter drives Cre-recombinase expression in POMC-producing cells in the pituitary and hypothalamus.

POMC-Cre female mice were crossed with homozygous Rosa26-LacZ [A, B] or Rosa26-TdTomato [C, D] male mice and tissues taken from their progeny were examined after fixing and sectioning; the X-gal reaction was used to visualize sites of LacZ expression and fluorescence was used to detect TdTomato. A and C] pituitary; B and D] arcuate nucleus of the hypothalamus (coronal sections). Ant, anterior lobe of the pituitary; I or Int, intermediate lobe of the pituitary; Arc N, arcuate nucleus of the hypothalamus. Scale bars, 200 μm.

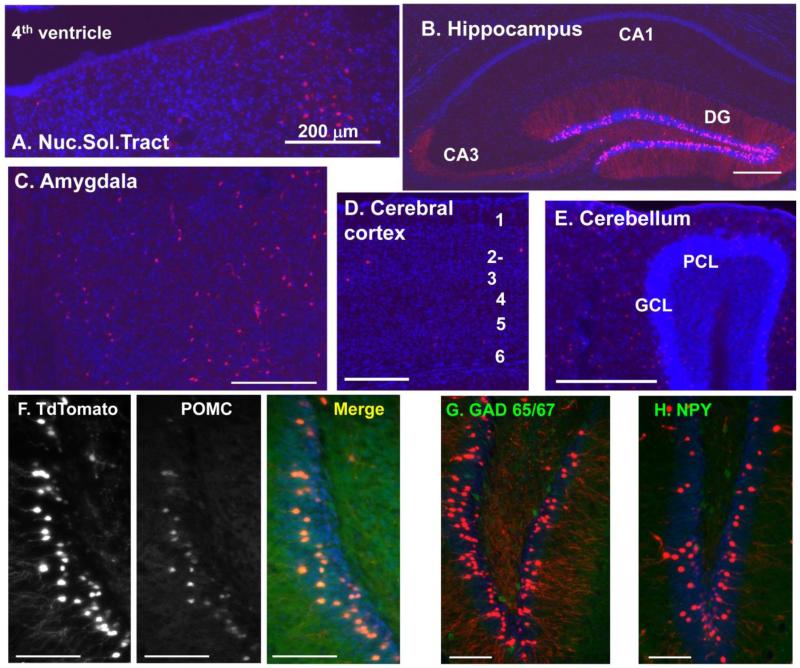

Although some expression of β-galactosidase was apparent in the hippocampus, the signal was not robust, so the Rosa26-TdTomato reporter mouse was utilized. Use of this fluorescent reporter confirmed the results obtained using the Rosa26-LacZ mouse in the pituitary and arcuate nucleus (Fig.2C, 2D); in addition, expression of TdTomato was apparent in the nucleus of the solitary tract, as expected (Fig. 3A). Use of the TdTomato reporter made signal readily detectable in the dentate gyrus and in scattered cells in the CA1-CA3 regions of the hippocampus (Fig.3B). Clear evidence of expression of Cre-recombinase at some point during development was also apparent in a subset of neurons in the amygdala (Fig.3C), in a very small population of neurons in the cortex (Fig.3D) and in scattered cells throughout the cerebellum (Fig.3E).

Fig. 3. The POMC promoter drives Cre-recombinase expression in cells not producing POMC in the adult.

POMC-Cre female mice were crossed with homozygous Rosa26-TdTomato male mice and tissues taken from progeny were examined for expression of TdTomato after fixation and sectioning: A] Nucleus of the solitary tract - TdTomato is detected in scattered cells in the adult; B] Hippocampus - TdTomato expressing cells are prevalent in the dentate gyrus; C] Amygdala (posteromedial and – lateral cortical amygdala, Bregma −2.0) (Paxinos and Franklin, 2008) - scattered TdTomato expressing cells are present; D] Cerebral cortex (layers numbered) and E] Cerebellum [layers as in (Tanaka et al. 2008); ML, molecular layer; PCL, Purkinje cell layer; GCL, granule cell layer; WM, white matter]. F, G, H] Higher power images of hippocampus stained for POMC product 16K fragment (F), glutamic acid decarboxylase (GAD 65/67) (G) and neuropeptide Y (NPY) (H). Expression of TdTomato indicates that the POMC promoter was active in these cells at some stage during development and that expression of all isoforms of Kalrn has been eliminated. Scale bars: A-E, 200 μm; F-H, 50 μm.

In order to determine which neurotransmitters the TdTomato-positive cells identified in the adult were producing, we turned to immunofluorescence. Five independent antisera to two POMC products, 16K fragment (Fig.3F) and ACTH (not shown), were utilized with identical results; surprisingly, nearly all the TdTomato-positive neurons, which activated POMC-Cre at some stage during development, were still producing POMC-derived peptides in the adult. As expected, in the adult hypothalamus, only about half of the adult hypothalamic TdTomato-positive neurons expressed POMC peptides (not shown), in agreement with Padilla et al (Padilla et al. 2012). The TdTomato-positive neurons in the hippocampus did not express GAD (Fig.3G), neuropeptide Y (NPY) (Fig.3H) or Vglut1 (not shown); the GAD and NPY patterns agreed with published reports (Ma et al. 2002;Ma et al. 2008). Although POMC is not expressed by all of the TdTomato-positive cells in the adult, any cell using the POMC promoter during development will lack Kalrn Exon 13 and be unable to produce any of the major Kalirin proteins. As expected, we never found POMC-peptide-producing neurons (green) which were not red (TdTomato-positive because they activated POMC-Cre at some time during development). The TdTomato-positive neurons in the amygdala did not express POMC peptides, GAD, NPY or Vglut1 (not shown).

These data provide the context for interpreting the consequences of eliminating the expression of full-length and ΔKalirin isoforms in all POMC cells. In the POMC-producing endocrine cells of the pituitary and in the POMC-producing neurons in the hypothalamus, Kal9 lacking the Sec14 domain and first four spectrin repeats (ΔKal9) is the major isoform expressed, in agreement with our previous Western blot analyses (Ferraro et al. 2007). In the POMC neurons in the NTS, hippocampus, amygdala and cortex, it is not clear whether Kal7 or Kal9 is the major isoform expressed.

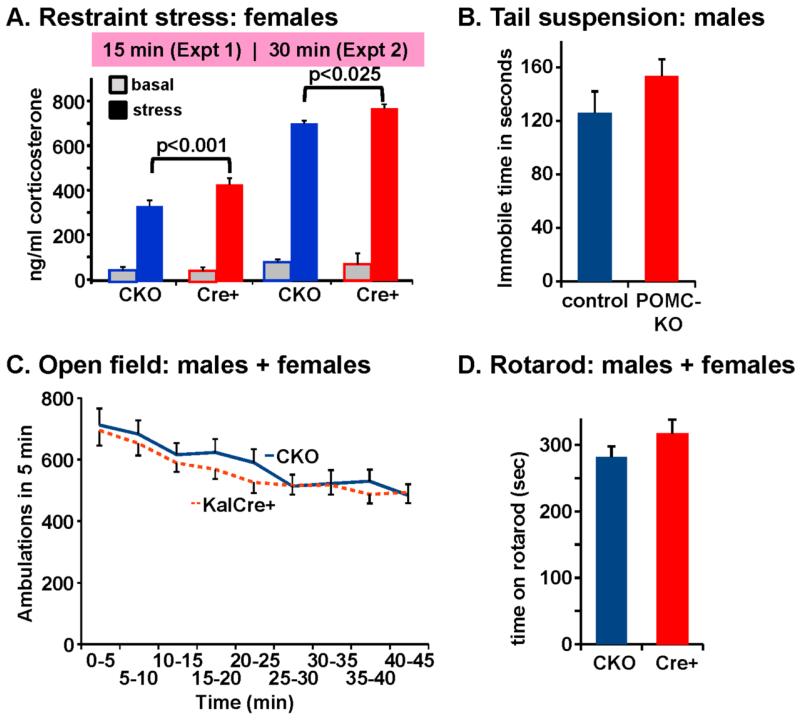

Kalirin Ablation in POMC Cells Leaves Many Physiological Responses and Behaviors Unaltered

We focused first on evaluating responses known to involve the POMC-producing cells of the adult. KalSRKO mice exhibit deficits in growth (Mandela et al. 2012). Since hypothalamic POMC-producing neurons are well established as key players in appetite and weight control (Ellacott and Cone 2006;Panaro and Cone 2013), we first evaluated weight gain in mice allowed free access to food; weight gain was unaltered in KalSRPOMC-KO vs. KalSRCKO mice (data not shown). Although deficits in maternal behavior were observed in KalSRKO mice, none were observed in the KalSRPOMC-KO mice. POMC-producing corticotropes play an essential role in the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis. Since restraint stress produces higher corticosterone levels in female than in male rodents (Mandela et al. 2012), the responses of male and female mice were analyzed separately. The response of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis to restraint stress is unaltered in male or female KalSRKO mice vs. KalSRCKO mice (Mandela et al. 2012). Similarly, after a 15 min restraint stress, no genotypic differences were observed in male KalSRPOMC-KO mice vs. KalSRCKO mice (Fig.4A). In contrast, after a 15 min restraint stress, KalSRPOMC-KO females showed a larger increase in serum corticosterone than did control females (p<0.001) (Fig.4A). By 2-way ANOVA (genotype x sex) of Experiment 1, there were no genotypic differences for males (N=6, each genotype; p=0.3), while there was a major effect of genotype for females (N=6 for each genotype; p<0.001; f(1,20)=65.85; η2=0.675), and corticosterone levels in females were higher than in the corresponding males of the same genotype (p<0.002). All the stressed female corticosterone values were significantly higher than the male values for each genotype (p<0.002) (not shown). The corticosterone values were also higher after a 30 min stress for both sexes and both genotypes, but the differences observed after a 15min stress were maintained: males did not differ by genotype; corticosterone levels in females were significantly higher than males for both genotypes, and corticosterone levels in female KalSRPOMC-KO mice were significantly higher than in KalSRCKO controls (p<0.025; f(1,5)=15.15; η2=0.791) (Fig.4A).

Fig. 4. Knockout of Kalirin in POMC cells increases serum corticosterone in females after restraint stress.

A] Mice were restrained in a ventilated disposable 50 ml tube for 15 min (Experiment 1) or 30 min (Experiment 2). Basal corticosterone was determined from submandibular pouch sampling at least 24h before the stress, and stressed levels of corticosterone were determined using trunk blood. B] Male mice (N=11 each genotype) were timed for immobility in the tail suspension test, with no significant genotypic differences (p=0.17). C] Male and female KalSRCKO and KalSRPOMC-KO mice (N=9 for each sex and genotype) were tested for mobility in the open field; no genotypic or sex differences were observed (RM-ANOVA p>0.6), so the data were pooled across sexes. D] Male and female KalSRCKO and KalSRPOMC-KO mice (N=6 for each sex and genotype) were tested for time to fall from the rotarod as its speed was increased; no genotypic or sex differences were observed.

Since glucocorticoids play a major role in depression, the behavior of the KalSRPOMC-KO mice in the tail suspension immobility test was evaluated; neither male KalSRPOMC-KO (Fig.4B) nor female KalSRPOMC-KO (not shown) mice showed a significant difference in immobility time in the 6-min test compared to the appropriate CKO littermates. Similarly, the ability of KalSRPOMC-KO mice to maintain core body temperature for 2 h in the cold room was normal (Bousquet-Moore et al. 2009;Mandela et al. 2012).

Both male and female KalSRKO mice exhibited profound deficiencies in neuromuscular function; grip strength and rotarod performance were compromised even in heterozygous animals (Mandela et al. 2012). Since locomotor ability affects the interpretation of many behavioral tests, the performance of KalSRPOMC-KO mice in the open field was evaluated; KalSRPOMC-KO mice of both sexes showed normal open field locomotion (Fig.4C). The KalSRPOMC-KO mice of both sexes were normal in open field, acoustic startle, novel object recognition, and exploratory behavior, so they are not hyperactive. The time to fall off the rotarod was also unaffected in KalSRPOMC-KO mice (Fig.4D). The changes observed in KalSRKO mice in the acoustic startle response and tests of exploratory behavior and novel object recognition (Bousquet-Moore et al. 2009;Mandela et al. 2012) were not observed in KalSRPOMC-KO mice (data not shown).

Kalirin Ablation in POMC Cells Reduces Anxiety-Like Behavior and Acquisition of Fear-Based Behavior

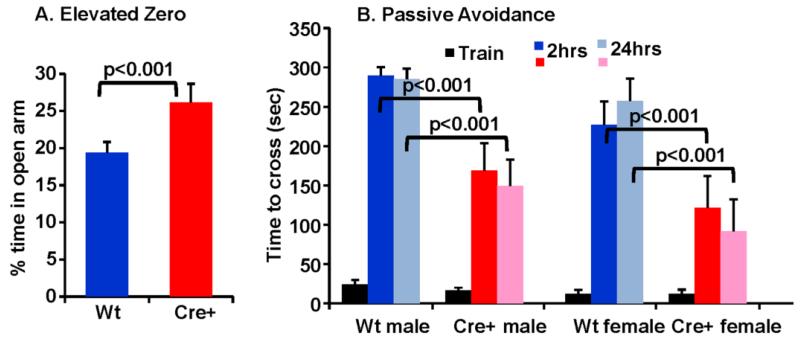

Both Kal7KO and KalSRKO mice exhibit a decrease in anxiety-like behavior and diminished passive avoidance conditioning (Ma et al. 2008;Mandela et al. 2012). The prevalence of POMC cells in the amygdala (Fig.3C) and hippocampus (Fig. 3B,F), which play essential roles in these behavioral responses, led us to evaluate KalSRPOMC-KO mice using these tests. Adult KalSRPOMC-KO mice were tested in the elevated zero maze (Fig.5A). Strikingly, KalSRPOMC-KO mice exhibited reduced anxiety-like behavior (increased time in the open arm), similar to the global KalSRKO mice (p<0.001). Using 2-way ANOVA, there was a major effect of genotype in each sex (p<0.01), with no effect of sex (p=0.728) (N=8 male, 9 female for each genotype). When pooled across sex, the difference is very significant (p<0.001; f(1,30)=14.63; η2=0.327). Data for male and female mice were pooled, since there was no effect of sex on this response.

fig. 5. Knockout of Kalirin in POMC cells decreases anxiety-like behavior and acquisition of fear-based behavior in both male and female mice.

A] Mice were tested for 5 min in the elevated zero maze and scored from videotapes by a blinded observer. B] Mice were tested for acquisition of fear-based behavior using a two compartment box with a footshock grid. Mice were trained once with the footshock and then tested without footshock at 2h and 24h later.

These mice were also evaluated using a passive avoidance paradigm, which tests hippocampal-dependent memory (Fig.5B). No genotype or sex differences were observed during the training session; KalSRCKO and KalSRPOMC-KO mice all took about 20 seconds to cross to the dark side of the chamber (p=0.438). Animals were tested 2 h after receiving a single foot shock when they crossed into the dark chamber and the same mice were tested again after 24 h. In comparison to KalSRCKO mice, littermate KalSRPOMC-KO mice exhibited a significantly decreased latency to cross over to the side in which they had received the foot shock (Fig.5B). Using 2-way ANOVA, there was a major effect of genotype in both sexes at 2h and at 24h (p<0.001 for both times; 2h, f(1,32)=15.08; η2=0.297; 24h, f(1,32)=27.26; η2=0.442). Females exhibited less hesitation than males to cross into the dark after 2h (p<0.04), but there was no effect of sex at 24h (N=9 males, 9 females of each genotype). Data for males and females were similar; a decreased latency to cross to the foot-shock paired side was apparent both at 2 h and at 24 h after the shock was given (p<0.001 for each time). Importantly, eliminating Kalirin expression only in POMC cells closely mimicked the impaired contextual fear learning seen in mice globally lacking Kal7 or all of the Kalirin isoforms (Kiraly et al. 2010;Ma et al. 2008;Mandela et al. 2012).

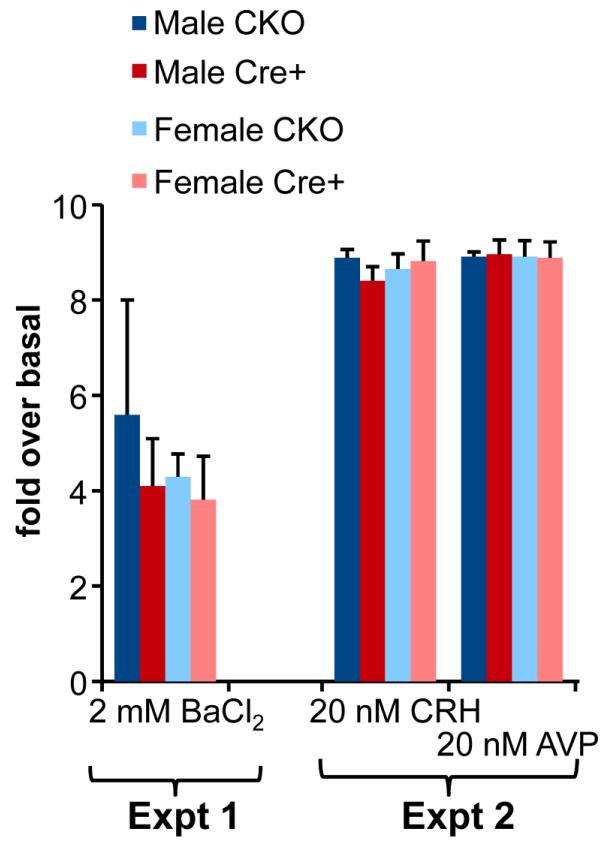

Kalirin Ablation in Corticotropes Does Not Disrupt Secretagogue-Stimulated Release of ACTH

Increased serum corticosterone in female KalSRPOMC-KO mice after restraint stress (Fig.4A), decreased anxiety-like behavior in both sexes (Fig.5A) and impaired acquisition of a passive avoidance behavior in both sexes (Fig.5B) revealed an important role for Kalirin in POMC cells. We turned to anterior pituitary corticotropes to evaluate the role of Kalirin in the regulated secretion of POMC products. Primary pituitary cultures prepared from global knockout KalSRKO mice were previously shown to exhibit increased basal secretion of growth hormone and prolactin, but secretion of POMC products was not evaluated (Mandela et al. 2012). Primary cultures were prepared from the anterior pituitaries of male and female littermate KalSRCKO (control) and KalSRPOMC-KO mice (Mandela et al. 2012) (Fig.6). Kalirin is known to play a role in the process by which peptide secreting cells target cargo to regulated secretory granules for storage rather than allowing it to be secreted basally (Ferraro et al. 2007). Basal and secretagogue-stimulated secretion of ACTH was quantified using an assay that detects ACTH(1-39) and ACTH biosynthetic intermediate, but not intact POMC or αMSH (Fig.6). Since the second GEF domain of Kalirin can be activated by binding to Gαq (Chhatriwala et al. 2007;Rojas et al. 2007), secretagogues known to act through different signaling pathways were tested. The secretory response of corticotropes to BaCl2, which acts as a substitute for Ca2+, was about a four-fold increase in secretion of ACTH, independent of sex or genotype. Corticotropin releasing hormone (CRH), which acts through the CRH1 receptor and Gαs to increase intracellular cAMP levels, stimulated secretion nine-fold over basal, with no effect of sex or genotype. Arginine vasopressin (AVP), which acts through the V1b receptor and Gαq to stimulate the phospholipase C pathway, also stimulated secretion of ACTH about nine-fold over the basal rate, independent of sex or genotype. Importantly, even in the absence of Kalirin, the response of corticotropes to AVP was normal (Aguilera et al. 2004;Kalantaridou et al. 2010;Ma et al. 1997;Wang et al. 2010).

Fig. 6. Pituitary cultures and ACTH secretion.

Anterior pituitary cultures were prepared separately from littermate male and female KalSRCKO (control) and KalSRPOMC-KO mice (Mandela et al. 2012). Three different secretagogues were tested: 2 mM BaCl2 (Expt.1), 20 nM CRH (Expt. 2), 20 nM AVP (Expt.2; a basal collection was made after CRH was removed and AVP was then applied). There were no consistent differences in stimulated secretion by sex or genotype across the experiments.

DISCUSSION

The global Kalirin knockout mouse (KalSRKO) exhibits a number of striking behavioral and physiological abnormalities (Mandela et al. 2012). While some of these abnormalities are shared with Kal7KO mice, others are not (Kiraly et al. 2010;Kiraly et al. 2013;Lemtiri-Chlieh et al. 2011;Ma et al. 2008;Mazzone et al. 2012); shared traits, such as the decrease in anxiety-like behavior and impaired contextual fear learning, may reflect the loss of Kal7. Since several of the traits exhibited by KalSRKO mice involve aberrant pituitary hormone secretion and several behavioral phenotypes suggest hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal involvement, we chose to test the effects of eliminating Kalirin expression only in cells which express POMC at some time during development or in adulthood. As expected, many of the behavioral and physiological deficits observed in KalSRKO mice did not occur in KalSRPOMC-KO mice; growth and lactation were normal, as was strength and performance on the rotarod. Remarkably, KalSRPOMC-KO mice exhibited a decrease in anxiety-like behavior and a decrease in their ability to acquire a passive avoidance task similar in magnitude to the deficits observed in KalSRKO mice (Fig. 5). In addition, female, but not male, KalSRPOMC-KO mice exhibited increased corticosterone secretion during restraint stress (Fig. 4). Several of the deficits identified in Kalirin knockout mice are also sex-specific (Mandela et al. 2012;Mazzone et al. 2012).

Any neurons that express POMC during development could contribute to the phenotype observed. Pituitary corticotropes control ACTH and thus corticosterone secretion while arcuate nucleus POMC neurons are an important source of endorphins (Khachaturian et al. 1985). Enhanced secretion of ACTH from corticotropes produces elevated corticosterone during stress (Fig. 4A), while elevated endorphin release by arcuate neurons could damp down anxiety-like behavior (Fig.5A) and depress fear-based memory acquisition (Fig.5B). Retrograde labeling demonstrated major projections from arcuate POMC neurons to the ventral tegmental area and amygdala (King and Hentges 2011). While most of the dentate gyrus neurons which express POMC during development continue to produce POMC in the adult (Fig. 3), some do not. Hippocampal pyramidal neurons help drive the hypothalamic-pituitary adrenal axis during stress but are suppressed by chronic exposure to corticosterone (Bhargava et al. 2000;Dallman et al. 1987;Young et al. 1990). Hippocampal Kalirin expression is up-regulated by estrogens in females (Ma et al. 2011;Mazzone et al. 2012), so it was reasonable to expect a sex-based difference in the corticosterone released after major stress (Fig.4A) and a major effect of Kalirin ablation which might show a sex difference (Fig.4A).

There is a controversy in the literature concerning which tissues and cells express Cre-recombinase in the POMCCre mouse used in this and many other studies (Balthasar et al. 2004;King and Hentges 2011;Morrison and Munzberg 2012;Padilla et al. 2010;Padilla et al. 2012). As this is a key point in interpreting the results obtained with the KalSRPOMC-KO mice, we mated the POMCCre mice with two reporter strains, one yielding β-galactosidase expression and one yielding TdTomato expression when Cre-recombinase is activated. There are advantages to each reporter, but the results were in good agreement. As expected, 5-10% of cells in the anterior pituitary (the corticotropes) and all of the cells of the intermediate pituitary were positive for Cre expression. The expected cluster of POMC-expressing neurons was observed in the arcuate nucleus of the hypothalamus, along with a smaller number of POMC-producing neurons in the nucleus of the solitary tract (Balthasar et al. 2004;King and Hentges 2011;Morrison and Munzberg 2012;Padilla et al. 2010;Padilla et al. 2012). TdTomato-positive cells were prominent in the dentate gyrus of the hippocampus; surprisingly, a large fraction of these neurons express POMC peptides in the adult. Although we did not observe NPY expression in TdTomato-expressing hippocampal neurons, neurons which produce POMC during development but switch to NPY production in the adult have been found in both the hippocampus and hypothalamus (Padilla et al. 2012). Our results for the dentate gyrus are in disagreement with a studying using a POMC-eGFP reporter mouse (Padilla et al. 2012), which revealed complete non-concordance of TdTomato expression (Cre recombinase expressed from POMC promoter some time during development) and eGFP expression (eGFP expression driven from a different POMC-promoter). Our identification of POMC-producing neurons in the dentate gyrus of the hippocampus is based on the use of five antisera to three regions of the POMC precursor (Eipper and Mains 1980;Khachaturian et al. 1985). The most likely biologically active POMC peptide produced by these cells is β-endorphin (Eipper and Mains 1980;Emeson and Eipper 1986). In addition, scattered TdTomato-positive cells were seen in the amygdala, a region of special interest for the behavioral effects observed. These amygdalar neurons are not known to produce POMC in the adult (Khachaturian et al. 1985) and were not recognized by any of the POMC antibodies used; it will be important to determine their identity. A minor population of cells expressing TdTomato was observed in the cerebellum and throughout the cerebral cortex. Loss of Kalirin expression in this widespread population of POMC cells must be factored into any interpretations of our behavioral and endocrine data.

A role for the second GEF domain of UNC-73, the C.elegans homolog of Kalirin, in neurosecretion is supported by analysis of multiple mutant strains (Hu et al. 2011;Steven et al. 2005). When the GEF1 domain of Kalirin is overexpressed in corticotrope tumor cells, the rate of constitutive-like secretion of POMC products increases (secretion of cleaved products without need for a stimulus), while stimulated secretion of mature POMC products is largely blocked (Ferraro et al. 2007). Pharmacological inhibition of Kalirin GEF1 activity in hippocampal neurons knocks out long-term potentiation, a process which requires increased regulated release of neurotransmitter (Lemtiri-Chlieh et al. 2011). Global elimination of Kalirin expression in the whole animal leads to an increase in basal PRL and GH secretion, with disruptions in growth, parturition and lactation (Mandela et al. 2012). Overexpression of PAM in corticotrope tumor cells causes elevated basal secretion of POMC products and blocks secretagogue-stimulated secretion; overexpression of the spectrin repeat region of Kalirin rescues stimulated secretion of peptides (Alam et al. 2001;Ciccotosto et al. 1999;Mains et al. 1999). The selective loss of Kalirin in POMC cells may alter their ability to release the correct products under basal or stimulated conditions. Selective loss of anxiety-like behavior and deficits in acquisition of passive avoidance behavior were not anticipated as consequences of targeting POMC cells (Fig.5). These data assign POMC cells a special role in anxiety- and fear-based behaviors, with a network of cells which is broadly distributed, including pituitary, hypothalamus, hippocampus, amygdala, and cortex. Knowledge of such a network could offer new targets for treatment.

Kal7KO mice exhibit a decrease in anxiety-like behavior and passive avoidance equivalent to the decrease observed in KalSRKO mice (Ma et al. 2008). Surprisingly, the deficits in these parameters in KalSRPOMC-KO mice are equally severe. There is negligible Kal7 in anterior pituitary or in the hypothalamus, which suggests that ablation of Kal7 should be without a direct effect on POMC cells in these two locations. The simplest explanation is that the lack of Kal7 affects signaling at excitatory endings elsewhere in the brain. Another possible explanation involves knockout of Kal7 in the widespread population of cells that produced POMC at some time during development - hippocampus, cortex, and amygdala are obvious candidates. Based on what is known about the role of Kal7 in other neurons, the absence of Kal7 presumably affects synapses with excitatory inputs onto functionally compromised dendritic spines of neurons no longer expressing Kalirin (Kiraly et al. 2011;Kiraly et al. 2010;Kiraly et al. 2013;Lemtiri-Chlieh et al. 2011;Ma et al. 2008;Mazzone et al. 2012). There are major projections from the arcuate nucleus of endorphin- and melanotropin-containing fibers into the amygdala, hippocampus and cortex which could all be altered by depressed Kalirin levels (Balthasar 2006;Herman et al. 2003;King and Hentges 2011;Vermetten and Bremner 2002). This demonstrates that loss of Kalirin expression in a relatively limited number of POMC endocrine cells and neurons has a dramatic effect on specific behaviors not conventionally attributed to the POMC-producing cells of the adult animal.

Highlights.

Kalirin, a multidomain RhoGEF, participates in multiple signaling pathways

Mice unable to express Kalirin exhibit blunted fear and anxiety

Proopiomelanocortin (POMC) is transiently expressed at diverse sites in development

Kalirin expression was eliminated everywhere that POMC was expressed

Loss of Kalirin expression in these cells altered anxiety and fear-based learning

Acknowledgments

We thank Darlene D’Amato for indefatigable technical support. This work was funded by National Institutes of Health Grant DK-32948. The NIH played no role in study design, data acquisition, analysis and interpretation, writing of the paper, or decision to submit the paper for publication.

Footnotes

FINANCIAL CONFLICT STATEMENT: The authors have nothing to disclose.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- Aguilera G, Nikodemova M, Wynn PC, Catt KJ. Corticotropin releasing hormone receptors: two decades later. Peptides. 2004;25:319–329. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2004.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alam MR, Caldwell BD, Johnson RC, Darlington DN, Mains RE, Eipper BA. Novel proteins that interact with the COOH-terminal cytosolic routing determinants of an integral membrane peptide-processing enzyme. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:28636–28640. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.45.28636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alam MR, Steveson TC, Johnson RC, Back N, Abraham B, Mains RE, Eipper BA. Signaling mediated by the cytosolic domain of peptidylglycine alpha-amidating monooxygenase. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2001;12:629–644. doi: 10.1091/mbc.12.3.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balthasar N. Genetic dissection of neuronal pathways controlling energy homeostasis. Obesity. 2006;14:222S–227S. doi: 10.1038/oby.2006.313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balthasar N, Coppari R, McMinn J, Liu SM, Elmquist JK, Lowell BB. Leptin receptor signaling in POMC neurons is required for normal body weight homeostasis. Neuron. 2004;42:983–991. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bargmann CI. Beyond the connectome: how neuromodulators shape neural circuits. Bioessays. 2012;34:458–465. doi: 10.1002/bies.201100185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beresewicz M, Kowalczyk JE, Jablocka B. Kalirin-7, a protein enriched in postsynaptic density, is involved in ischemic signal transduction. Neurochem. Res. 2008;33:1789–1794. doi: 10.1007/s11064-008-9631-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhargava A, Meijer OC, Dallman MF, Pearce D. Plasma membrane calcium pump isoform 1 gene expression is repressed by corticosterone and stress in rat hippocampus. J. Neurosci. 2000;20:3129–3138. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-09-03129.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bousquet-Moore D, Ma XM, Nillni EA, Czyzyk TA, Pintar JE, Eipper BA, Mains RE. Reversal of physiological deficits caused by diminished levels of peptidylglycine alpha-amidating monooxygenase by dietary copper. Endocrinology. 2009;150:1739–1747. doi: 10.1210/en.2008-1202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bousquet-Moore D, Prohaska JR, Nillni EA, Czyzyk TA, Wetsel WC, Mains RE, Eipper BA. Interactions of peptide amidation and copper: novel biomarkers and mechanisms of neural dysfunction. Neurobiol. Dis. 2010;37:130–140. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2009.09.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Q, Xiong X, Lee TH, Liu Y, Wetsel WC, Zhang X. Neural plasticity and addiction: integrin-linked kinase and cocaine behavioral sensitization. J. Neurochem. 2008;107:679–689. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05619.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chhatriwala MK, Betts L, Worthylake DK, Sondek J. The DH and PH domains of Trio coordinately engage Rho GTPases for their efficient activation. J. Mol. Biol. 2007;368:1307–1320. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.02.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciccotosto GD, Schiller MR, Eipper BA, Mains RE. Induction of integral membrane PAM expression in AtT-20 cells alters the storage and trafficking of POMC and PC1. J. Cell Biol. 1999;144:459–471. doi: 10.1083/jcb.144.3.459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dallman MF, Akana SF, Jacobson L, Levin N, Cascio CS, Shinsako J. Characterization of corticosterone feedback regulation of ACTH secretion. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1987;512:402–414. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1987.tb24976.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eipper BA, Mains RE. Structure and biosynthesis of pro-adrenocorticotropin/endorphin and related peptides. Endocr. Rev. 1980;1:1–27. doi: 10.1210/edrv-1-1-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellacott KL, Cone RD. The role of the central melanocortin system in the regulation of food intake and energy homeostasis: lessons from mouse models. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B. 2006;361:1265–1274. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2006.1861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emeson RB, Eipper BA. Characterization of pro-ACTH/endorphin-derived peptides in rat hypothalamus. J. Neurosci. 1986;6:837–849. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.06-03-00837.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferraro F, Ma XM, Sobota JA, Eipper BA, Mains RE. Kalirin/Trio Rho guanine nucleotide exchange factors regulate a novel step in secretory granule maturation. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2007;18:4813–4825. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-05-0503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaier ED, Miller MB, Ralle M, Aryal D, Wetsel WC, Mains RE, Eipper BA. Peptidylglycine alpha-amidating monooxygenase heterozygosity alters brain copper handling with region specificity. J. Neurochem. 2013;127:605–619. doi: 10.1111/jnc.12438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haller J, Bakos N, Rodriguez RM, Caron MG, Wetsel WC, Liposits Z. Behavioral responses to social stress in noradrenaline transporter knockout mice: effects on social behavior and depression. Brain Res. Bull. 2002;58:279–284. doi: 10.1016/s0361-9230(02)00789-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herman JP, Figueiredo H, Mueller NK, Ulric-Lai Y, Choi DC, Cullinan WE. Central mechanisms of stress integration: hierarchical circuitry controlling hypothalamo pituitary adrenocortical responsiveness. Front. Neuroendocrinol. 2003;24:151–180. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2003.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu S, Pawson T, Steven RM. Unc-73/trio RhoGEF-2 activity modulates C.elegans motility through changes in neurotransmitter signaling upstream of the GSA-1/Galphas pathway. Genetics. 2011;189:137–151. doi: 10.1534/genetics.111.131227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang S, Elensite P, Carter C, Shah N, Mandela P, Eipper BA, Mains RE, Allen M, Bruzzaniti A. The Rho-GEF Kalirin Regulates Trabecular and Cortical Bone Mass Through Effects on Both Osteoblasts and Osteoclasts. Bone Min. Res. 2013;60:235–245. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson RC, Penzes P, Eipper BA, Mains RE. Isoforms of kalirin, a neuronal Dbl family member, generated through use of different 5′- and 3′-ends along with an internal translational initiation site. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:19324–19333. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M000676200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalantaridou SN, Zoumakis E, Makrigiannakis A, Lavasidis LG, Vrekoussis T, Chrousos GP. Corticotropin-releasing hormone, stress and human reproduction: an update. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2010;85:33–39. doi: 10.1016/j.jri.2010.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawai T, Sanjo H, Akira S. Duet is a novel serine/threonine kinase with Dbl-Homology (DH) and Pleckstrin-Homology (PH) domains. Gene. 1999;227:249–255. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(98)00605-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khachaturian H, Lewis ME, Schafer MKH, Watson SJ. Anatomy of the CNS opioid systems. Trends Neurosci. 1985;8:111–119. [Google Scholar]

- King CM, Hentges ST. Relative Number and Distribution of Murine Hypothalamic Proopiomelanocortin Neurons Innervating Distinct Target Sites. PLoS One. 2011;6:e25864. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0025864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiraly DD, Lemtiri-Chlieh F, Levine ES, Mains RE, Eipper BA. Kalirin Binds the NR2B Subunit of the NMDA Receptor, Altering Its Synaptic Localization and Function. J. Neurosci. 2011;31:12554–12565. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3143-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiraly DD, Ma XM, Mazzone CM, Xin X, Mains RE. Behavioral and Morphological Responses to Cocaine Require Kalirin7. Biol. Psychiatry. 2010;68:249–255. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.03.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiraly DD, Nemirovsky NE, Larese TP, Tomek SE, Yahn SL, Olive MF, Eipper BA, Mains RE. Constitutive knockout of Kalirin-7 leads to increased rates of cocaine self-administration. Mol. Pharmacol. 2013;84:582–590. doi: 10.1124/mol.113.087106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krug T, Manso H, Gouveia L, Sobral J, Xavier JM, Oliveira SA. Kalirin: a novel genetic risk factor for ischemic stroke. Hum. Genet. 2010;127:513–523. doi: 10.1007/s00439-010-0790-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kushima I, Nakamura Y, Aleksic B, Ikeda M, Ito Y, Ozaki N. Resequencing and association analysis of the KALRN and EPHB1 genes and their contribution to schizophrenia susceptibility. Schizo. Bull. 2012;38:552–560. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbq118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemtiri-Chlieh F, Zhao L, Kiraly DD, Eipper BA, Mains RE, Levine ES. Kalirin-7 is necessary for normal NMDA receptor-dependent synaptic plasticity. BMC Neurosci. 2011;12:126. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-12-126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma XM, Huang JP, Kim EJ, Zhu Q, Kuchel GA, Mains RE, Eipper BA. Kalirin-7, an Important Component of Excitatory Synapses, is Regulated by Estradiol in Hippocampal Neurons. Hippocampus. 2011;21:661–677. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma XM, Kiraly DD, Gaier ED, Wang Y, Kim EJ, Levine ES, Eipper BA, Mains RE. Kalirin-7 Is Required for Synaptic Structure and Function. J. Neurosci. 2008;28:12368–12382. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4269-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma XM, Levy A, Lightman SL. Emergence of an isolated arginine vasopressin (AVP) response to stress after repeated restraint: a study of both AVP and corticotropin-releasing hormone messenger ribonucleic acid (RNA) and heteronuclear RNA. Endocrinology. 1997;138:4351–4357. doi: 10.1210/endo.138.10.5446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma XM, Mains RE, Eipper BA. Plasticity in hippocampal peptidergic systems induced by repeated electroconvulsive shock. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2002;27:55–71. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(02)00284-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma XM, Wang Y, Ferraro F, Mains RE, Eipper BA. Kalirin-7 Is an Essential Component of both Shaft and Spine Excitatory Synapses in Hippocampal Interneurons. J. Neurosci. 2008;28:711–724. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5283-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mains RE, Alam MR, Johnson RC, Darlington DN, Back N, Hand TA, Eipper BA. Kalirin, a Multifunctional PAM COOH-terminal Domain Interactor Protein, Affects Cytoskeletal Organization and ACTH Secretion from AtT-20 Cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:2929–2937. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.5.2929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mains RE, Kiraly DD, Eipper-Mains JE, Ma XM, Eipper BA. Kalrn promoter usage and isoform expression respond to chronic cocaine exposure. BMC Neurosci. 2011;12:20. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-12-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandela P, Ma XM. Kalirin, a Key Player in Synapse Formation, Is Implicated in Human Diseases. Neural Plasticity. 20122012 doi: 10.1155/2012/728161. doi:10.1155/2012/728161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandela P, Yankova M, Conti LH, Ma XM, Grady J, Eipper BA, Mains RE. Kalrn plays key roles within and outside of the nervous system. BMC Neurosci. 2012;13:136. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-13-136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazzone CM, Larese TP, Kiraly DD, Eipper BA, Mains RE. Analysis of Kalirin-7 knockout mice reveals different effects in female mice. Mol. Pharmacol. 2012;82:1241–1249. doi: 10.1124/mol.112.080838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McPherson CE, Eipper BA, Mains RE. Kalirin expression is regulated by multiple promoters. J. Mol. Neurosci. 2004;22:51–62. doi: 10.1385/JMN:22:1-2:51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller MB, Yan Y, Eipper BA, Mains RE. Neuronal Rho GEFs in Synaptic Physiology and Behavior. Neuroscientist. 2013 doi: 10.1177/1073858413475486. PMID: 23401188,in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison CD, Munzberg H. Capricious Cre: The Devil Is in the Details. Endocrinology. 2012;153:1005–1007. doi: 10.1210/en.2011-2169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nathan C, Calingasan N, Nezezon J, Ding A, Lucia MS, Beal MF. Protection from Alzheimer’s-like disease in the mouse by genetic ablation of inducible nitric oxide synthase. J. Exp. Med. 2005;202:1163–1169. doi: 10.1084/jem.20051529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padilla SL, Carmody JS, Zeltser LM. POMC-expressing progenitors give rise to antagonistic neuronal populations in hypothalamic feeding circuits. Nat. Medicine. 2010;16:403–405. doi: 10.1038/nm.2126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padilla SL, Reef D, Zeltser LM. Defining POMC Neurons Using Transgenic Reagents: Impact of Transient Pomc Expression in Diverse Immature Neuronal Populations. Endocrinology. 2012;153:1219–1231. doi: 10.1210/en.2011-1665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panaro BL, Cone RD. Melanocortin-4 receptor mutations paradoxically reduce preference for palatable foods. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2013;110:7050–7055. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1304707110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G, Franklin KB. The Mouse Brain In Stereotaxic Coordinates. Academic Press; New York: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Penzes P, Cahill ME, Jones KA, VanLeeuwen JE, Woolfrey KM. Dendritic spine pathology in neuropsychiatric disorder. Nat. Neurosci. 2011;14:285–293. doi: 10.1038/nn.2741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penzes P, Johnson RC, Kambampati V, Mains RE, Eipper BA. Distinct roles for the two Rho GDT/GTP exchange factor domains of Kalirin in regulation of neurite outgrowth and neuronal morphology. J. Neurosci. 2001;21:8426–8434. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-21-08426.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penzes P, Johnson RC, Sattler R, Zhang X, Huganir RL, Kambampati V, Mains RE, Eipper BA. The neuronal Rho-GEF Kalirin-7 interacts with PDZ domain-containing proteins and regulates dendritic morphogenesis. Neuron. 2001;29:229–242. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00193-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pillai-Nair N, Panicker AK, Rodriguiz RM, Miller K, Wetsel WC, Maness PF. NCAM-Secreting transgenic mice display abnormalities in GABAergic interneurons and alterations in behavior. J. Neurosci. 2005;25:4659–4671. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0565-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pogorelov VM, Insco ML, Caron MG, Wetsel WC. Novelty seeking and stereotypic activation of behavior in mice with disruption of the Dat1 gene. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2005;30:1818–1831. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabiner CA, Mains RE, Eipper BA. Kalirin: a dual Rho guanine nucleotide exchange factor that is so much more than the sum of its parts. Neuroscientist. 2005;11:148–160. doi: 10.1177/1073858404271250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ratovitski EA, Alam MR, Quick RA, McMillan A, Bao C, Hand TA, Johnson RC, Mains RE, Eipper BA, Lowenstein CJ. Kalirin inhibition of inducible nitric oxide synthase. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:993–999. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.2.993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rojas RJ, Yohe ME, Gershburg S, Kawano T, Kozasa T, Sondek J. Gαq directly activates p63RhoGEF and Trio via a conserved extension of the DH-associated PH domain. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:29201–29210. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M703458200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soriano P. Generalized lacZ expression with the ROSA26 Cre reporter strain. Nat. Genet. 1999;21:70–71. doi: 10.1038/5007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steru L, Chermat R, Thierry B, Simon P. The tail suspension test: a new method for screening antidepressants in mice. Psychopharmacology. 1985;85:367–370. doi: 10.1007/BF00428203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steven R, Zhang L, Culotti J, Pawson T. The unc-73/Trio RhoGEF2 domain is required in separate isoforms for the regulation of pharynx pumping and normal neurotransmission in C.elegans. Genes & Devel. 2005;19:2016–2029. doi: 10.1101/gad.1319905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka M, Yamaguchi K, Tatsukawa T, Theis M, Willecke K, Itohara S. Connexin43 and Bergmann glial gap junctions in cerebellar function. Front. Neurosci. 2008;2:225–233. doi: 10.3389/neuro.01.038.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vermetten E, Bremner DJ. Circuits and systems in stress, I. preclinical studies. Depress Anxiety. 2002;15:126–147. doi: 10.1002/da.10016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Hauser ER, Shah SH, Pericak-Vance MA, Goldschmidt-Clermont PJ, Vance JM. Peakwide mapping on chromosome 3q13 identifies the Kalirin gene as a novel candidate gene for coronary artery disease. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2007;80:650–663. doi: 10.1086/512981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang SS, Yan XB, Hofman MA, Swaab DF, Zhou JN. Increased expression level of corticotropin-releasing hormone in the amygdala and in the hypothalamus in rats exposed to chronic unpredictable mild stress. Neurosci. Bull. 2010;26:297–303. doi: 10.1007/s12264-010-0329-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu JH, Fanaroff AC, Sharma KC, Zhang L, Smith LS, Brian L, Eipper BA, Mains RE, Freedman NJ. Kalirin Promotes Neointimal Hyperplasia by Activating Rac in Smooth Muscle Cells. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2012;33:702–708. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.112.300234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Youn HS, Jeoung MK, Koo YB, Ji H, Markesbery WR, Ji I, Ji TH. Kalirin is under-expressed in Alzheimer’s Disease hippocampus. J. Alzheimers Disease. 2007;11:385–397. doi: 10.3233/jad-2007-11314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Youn HS, Ji I, Ji H, Markesbery WR, Ji TH. Under-expression of Kalirin-7 Increases iNOS activity in cultured cells and correlates to elevated iNOS activity in Alzheimer’s disease hippocampus. J. Alzheimers Disease. 2007;12:271–281. doi: 10.3233/jad-2007-12309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young EA, Akana SF, Dallman MF. Decreased sensitivity to glucocorticoid fast feedback in chronically stressed rats. Neuroendocrinology. 1990;51:536–542. doi: 10.1159/000125388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]