Abstract

SIRT6 is a histone deacetylase that has been proposed as a potential therapeutic target for metabolic disorders and the prevention of age-associated diseases. Thus the identification of compounds that modulate SIRT6 activity could be of great therapeutic importance. We have previously developed an H3K9 deacetylation guided assay with SIRT6 coated magnetic beads (SIRT6-MB). With the developed assay, we identified quercetin, naringenin and vitexin as SIRT6 inhibitors from T. foenum-graecum seed extract using a candidate approach. Currently, the predominant method for the identification of active compounds from a plant extract is carried out through a dereplication process. A novel targeted approach for the direct identification of active compounds from a complex matrix could save time and resources. Herein, we report the application of the SIRT6-MB for ‘fishing’ experiments utilizing T. foenum-graecum seed extract. In which orientin, and seventeen other compounds were identified as SIRT6 binders. This is the first use of this method for ‘fishing’ out active ligands from a botanical matrix, and sets the basis for the identification of active compounds from a complex matrix.

Keywords: SIRT6, Fenugreek seed extract, Orientin, Ligand fishing, Magnetic beads

1. Introduction

Trigonella foenum-graecum L. (fenugreek, Fabaceae) is extensively cultivated as a food crop in India, the Mediterranean regions, North Africa and Yemen [1]. Besides culinary use, T. foenum-graecum has been used as a remedy for cough, to soften boils [2], to prevent anemia [3], to promote lactation and as a yang tonic [4]. However, it is perhaps best known in modern phytotherapy for its use in diabetes [5,6].

Human studies of T. foenum-graecum have demonstrated a decrease in blood glucose from water extracts of the seed [7-9] and favorable effects on serum lipids [9,10]. In addition, a meta-analysis has suggested that T. foenum-graecum seed may improve glycemic control in type 2 diabetes [11]. While the mechanisms of action of these effects are not currently established, multiple constituents: the fiber, gum [12], saponins [13], guanides [14] and 4-hydroxy isoleucine [15] are suggested to be responsible.

Sirtuins are a family of NAD+-dependent histone deacetylases (HDACs) that have been implicated to be important regulators in the aging process, cancers and metabolic diseases [16]. SIRT6 knockout mice show a premature aging phenotype and shortened lifespan, developing several acute degenerative processes by three weeks of age, including decreased serum glucose and insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) levels [17]. SIRT6 also has a role in glycolysis, where activation of SIRT6 reduces glycolytic activity and controls the expression of multiple glycolytic genes [18,19]. Recent evidence, points to SIRT6 as a master regulator of glucose homeostasis and a target for the treatment of obesity and insulin resistant diabetes [19,20]. In animal models, SIRT6 activity suppresses gluconeogenesis and normalizes glycemia [20].

In previous research using H3K9 deacetylation guided assay, we demonstrated that the flavonoids quercetin and vitexin, contained within T. foenum-graecum seed extract (TFGExt), were SIRT6 modulators. While they inhibited deacetylation of H3K9Ac, quercetin and vitexin did not have the same level of inhibition as 1% fenugreek seed extract, suggesting that there were additional, and as of yet, unidentified modulators of SIRT6 in the extract. Considering the use of TFGExt in Type II diabetes, the identification of novel modulators of SIRT6 activity from TFGExt could be beneficial.

Currently, the identification of active compounds is carried out through a dereplication process, where bioassays of plant extracts are used to identify and isolate the active compounds through a bioassay-guided fractionation process [21]. While dereplication has been proven effective, an active compound that is only present in minute quantities could be missed.

A novel targeted approach is the direct identification of active compounds for a target from a complex matrix using a protein-coated bead. We have previously demonstrated the success of this approach with Acetylcholine esterase (AChE). In that study, AChE was immobilized onto the surface of magnetic beads, and the protein coated magnetic beads were used to fish out active compounds from Melodinus fusiformis, which lead to the identification of an inhibitor of AChE [22].

In this manuscript, SIRT6 was immobilized onto the surface of magnetic beads in an attempt to identify additional ligands from the crude plant extract, TFGExt, that possess SIRT6 activity. Herein, we report for the first time, the use of SIRT6-coated magnetic bead for the isolation of novel modulators from TFGExt and the identification of orientin as a novel SIRT6 inhibitor.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Materials

2-(N-morpholino)ethanesulfonic acid (MES) was purchased from EMD-Calbiochem (Gibbstown, NJ). 1-Ethyl-3-(3-methylaminopropyl)carbodiimide (EDC), gluteraldehyde, hydroxylamine hydrochloride, Dithiothreitol (DTT) potassium phosphate dibasic, pyridine (99.8%), sodium azide, sodium cyanoborohydride, sodium chloride, tryptone, yeast extract, glucose, β-mercaptoethanol, EDTA, Isopropyl β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG), trizma base, calcium chloride, glycerol and sodium phosphate monobasic, quercetin, vitexin, naringenin, orientin were obtained from Sigma–Aldrich Chemical Co. (Milwaukee, WI). Species verification of lot number 401255 (T. foenum-graecum) was from HerbPharm (Williams, OR). N-Hydroxysulfosuccinimide (Sulfo-NHS) was from Pierce (Rockford, IL). Solutions were prepared using purified water from a Millipore MilliQ system (Millipore Corporation, Bedford, MA). BcMag amine-terminated magnetic beads (50 mg/mL, 1 μm) were purchased from Bioclone, Inc. (San Diego, CA). The manual magnetic separator Dynal MPC-S was from Invitrogen Corporation (Carlsbad, CA).

2.2. Expression and purification of GST-tagged SIRT6 proteins in E. coli

Recombinant SIRT6 protein was expressed in E. coli (BL21, Rosetta strain, Novagen) and purified as previously described [23]. In brief, an overnight 5 mL culture of a single bacterial colony harboring the pGEX SIRT6 plasmid was used to inoculate 1 L of Luria Broth medium (10 g/L tryptone, 5 g/L yeast extract, 10 g/L NaCl, pH = 7.0) containing 2 g/L glucose. The cultures were grown at 37 °C and 200 rpm, and protein production was induced by adding 50 μM IPTG. After 3 h the bacteria were pelleted and flash frozen. Bacterial pellets were resuspended in 12.5 mL ice-cold lysis buffer (20 mM Tris pH = 8.0, 200 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 5 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 10% glycerol) including protease inhibitors and lysed by sonication (3× 15 s bursts with 30 s intervals on ice using a Branson digital sonifier). The GST-SIRT6 fusion proteins were bound to 400 μL glutathione sepharose resin (GE Healthcare) for 2 h at 4 °C on a rotator. The resin was washed twice with ice-cold lysis buffer, twice with ice-cold cleavage buffer (20 mM Tris pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM CaCl2, 5 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 10% glycerol), and finally resuspended in 600 μL of cleavage buffer. The SIRT6 protein was released from the resin be adding 4 μL of thrombin (1 U/μL, Novagen) and incubation at 4 °C overnight. The resin was pelleted and the supernatant was added to 50 μL benzamidine-agarose (Sigma). After 30 min at room temperature, the agarose was pelleted and the supernatant was further purified using a Superose 6 column in an AKTA FPLC system (GE Healthcare). Fractions containing monomeric SIRT6 protein were pooled and dialyzed overnight against 1× PBS + 20% glycerol, and finally stored as frozen aliquots at −80 °C.

2.3. Immobilization of SIRT6 onto the surface of magnetic beads

The amine groups on the BcMag beads and the SIRT-6 protein were linked by a previously described method [24]. Briefly, 0.5 mL (25 mg) of BcMag beads were rinsed with 1 mL of MES [100 mM, pH 5.5] in a 2 mL microcentrifuge tube. After magnetic separation, the supernatant was discarded, and the BcMag beads were suspended in 300 μL of MES [100 mM, pH 5.5] and 260 μg of SIRT6 protein. Fifty microliters of a mixture of 10 mg of EDC and 15 mg of sulfo-NHS in 1 mL of water were added and the mixture was vortex-mixed for 5 min and left for 3 h at 4 °C with gentle rotation. This was followed by the addition of 20 μL of 1 M hydroxylamine, and the mixture was left for 30 min at 4 °C with gentle rotation. The supernatant was discarded and the SIRT6-MB was rinsed three times with 1 mL of storage buffer (phosphate buffer [10 mM, pH7.4] containing 150 mM NaCl and 0.02% sodium azide). Histone deacetylation assay by mass spectrometry [23] was carried out to confirm the activity of immobilized SIRT6. For the control-MBs, SIRT6 was not added.

2.4. T. foenum-graecum seed extract preparation

Species verification of lot number 401255 (Herb Pharm, Williams, OR) of organic T. foenum-graecum semen was performed by macroscopic and microscopic examination and HPTLC analysis. A typical protocol for the manufacture of ethanolic extracts was followed for plant extractions [25]. T. foenum-graecum seed was extracted by maceration for 3 weeks at 1:2.5 ratio at 72% ethanol, ratio expressed as mass raw plant material (T. foenum-graecum seed) in weight (g) per volume (mL) of extraction solvent.

2.5. Fingerprinting of Trigonella foenum-graecum extract by mass spectrometry

A previously described method [26] for separation of polyphenols was used to establish a fingerprint for the TFGExt. Briefly, 1% (v/v) TFGExt was analyzed by mass spectrometry using a system composed of an Agilent Technologies 1100 LC/MSD equipped with a G1322A degasser, G1312A binary pump, G1367A autosampler, G1316A column thermostat, G1315A diode array detector and G1946D mass spectrometer equipped with an electrospray ionization (ESI) interface. Selected ion monitoring (SIM) chromatograms were acquired using Chemstation software, Rev. A.10.02. For the separation of the polyphenols, a reversed-phase Varian Pursuit XRs C18 analytical column (250 mm × 4.6 mm id, 5 μm particles) was used. The column was operated at 25 °C. Gradient elution was used for the separation. The two solvents used to make the gradient were (A) 25% methanol in 1% acetic acid, and (B) 75% methanol in 1% acetic acid. The solvent gradient in volumetric ratios of solvents A and B was as follows:0–30 min, 100 A/0 B; 30–45 min, 82 A/18 B; 45–65 min, 72 A/28 B; 65–85 min, 60 A/40 B; 85 min, 0 A/100 B. The flow rate was 0.75 mL/min and the injection volume was 20 μL.

2.6. Fishing for SIRT6 specific substrate/inhibitor in Trigonella foenum-graecum seed extract

TFGExt was diluted with ammonium acetate buffer [10 mM, pH 7.4] to prepare 1% (v/v) solution. SIRT6-MB were suspended in 1 mL of the 1% (v/v) of TFGExt. The suspension was vortexed and was constantly mixed using a roller at 4 °C for 15 min. Later, the SIRT6-MB was separated using a magnetic tray and the supernatant was collected (Load). The SIRT6-MB was washed twice (10 min) with 0.5 mL of 10 mM ammonium acetate, pH 7.4 and the supernatant was discarded. Following this wash, SIRT6-MB was incubated with 0.5 mL of 20:80 MEOH:10 mM Amm. Acetate buffer, pH 7.4 for 15 min and the supernatant was collected (Elute) after magnetic separation. The diluted TFGExt, Load and elute were analyzed by mass spectrometry (as described in Section 2.4).

3. Results and discussion

The use of protein-coated magnetic beads for ligand fishing in complex matrices allows for the identification of a compound(s) that is not concentration dependent but rather affinity dependent. This allows an advantage over the classic dereplication process, which is concentration dependent.

In this study, the SIRT6 coated magnetic beads were used to ‘fish’ active compounds from TFGExt. The optimal conditions required for the ligand fishing experiments using the SIRT6-MB were carried out using known inhibitors of the SIRT6 protein including: quercetin, naringenin and vitexin [23,24,27], representing strong, moderate and weak binder, respectively. The length of incubation time (5, 10 or 15 min) of ligands with the SIRT6-MB, was the initial parameter studied. It was determined that while quercetin, naringenin and vitexin were retained in both the 5 and 10 min incubations, 15 min was the optimal incubation time. After incubation, the SIRT6-MBs were washed twice with ammonium acetate buffer and eluted by incubating the SIRT6-MB with the elution buffer (ammonium acetate buffer [10 mM, pH 7.4] containing 10% methanol) for 15 min. While, a concentration of 10% methanol in the elution buffer worked, a marked improvement was observed when the methanol concentration was increased to 20%.

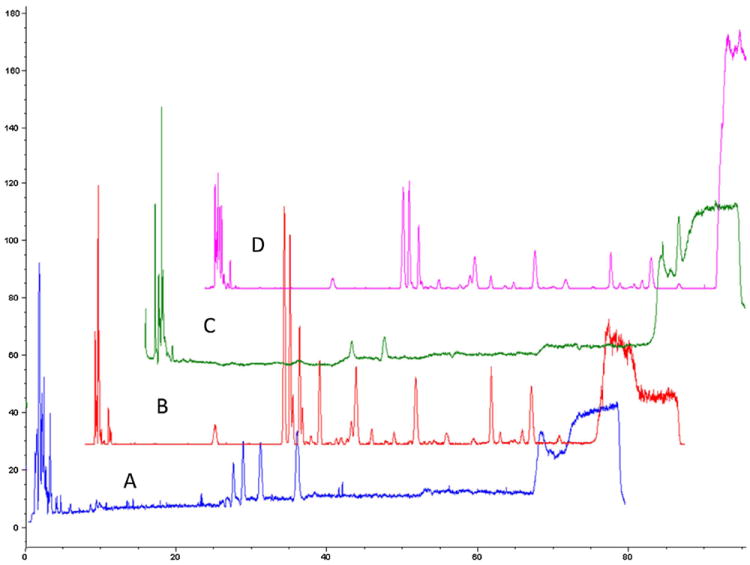

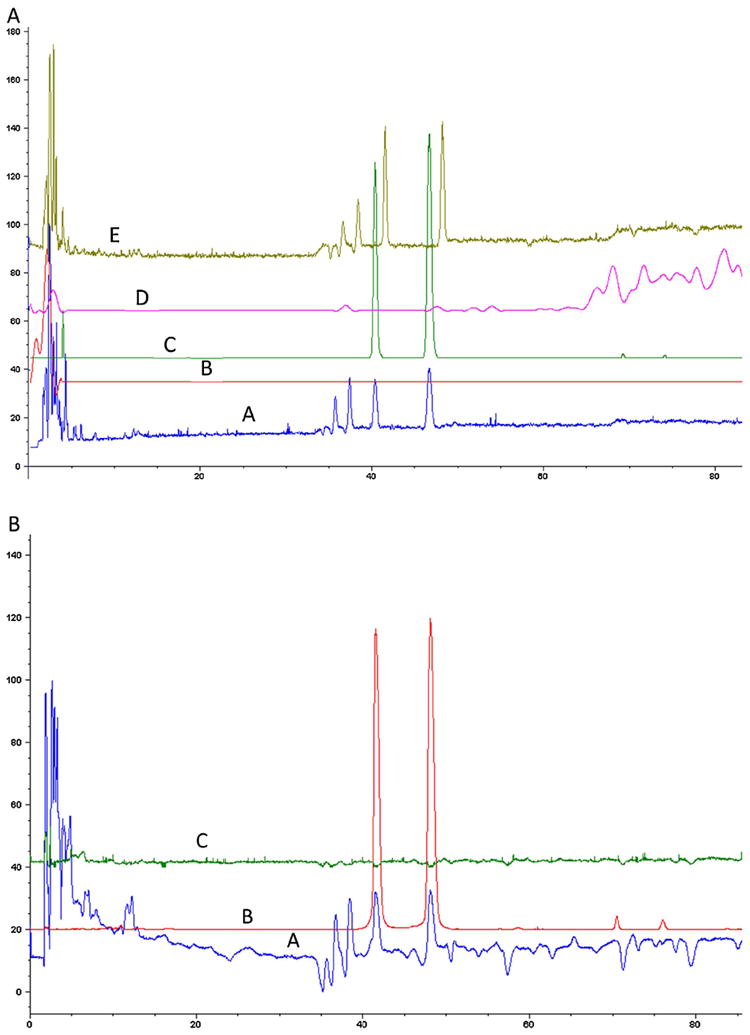

Prior to running the “fishing” experiments, a fingerprint of TFGExt was carried out on the LC–MS in both positive and negative mode at the following mass ranges: 150–500 m/z and 500–1000 m/z (Fig. 1), using a previously described method for separation of polyphenols with slight modifications [26]. The extract was subsequently spiked with T. foenum-graecum flavonoids vitexin, quercetin and naringenin to identify the retention time of these known components with the LC–MS method in negative ionization mode (Fig. 2A) and in positive ionization mode (Fig. 2B). The identification of vitexin and naringenin was seen in both negative ionization mode (Fig. 2A(C) (m/z 431.2) and Fig. 2A(D) (m/z 271.2), respectively) and in positive ionization mode (Fig. 2B(B) (m/z 433.2) and Fig. 2B(C) (m/z 273.2) respectively), while quercetin was only seen in negative ionization mode (Fig. 2A(B) (m/z 301.2)).

Fig. 1.

HPLC–MS analysis of a 1% (v/v) ethanolic extract of T. foenum-graecum seed. The separation was carried out on a reversed-phase Varian Pursuit XRs C18 analytical column (250 mm × 4.6 mm id, 5 μM particles). The flow rate was 0.75 mL/min and the injection volume was 20 μL The analysis was carried out in both a negative ionization mode with a mass range of m/z 150–500 (A) and m/z 500–1000 (B) and positive ionization mode with a scan range of m/z 150–500 (C) and m/z of 500–1000 (D).

Fig. 2.

(A) HPLC–MS analysis in negative ionization mode with a scan range of m/z 150–500 was carried out of a 1% (v/v) ethanolic extract of T. foenum-graecum seed (A) and the extracted ion chromatogram of m/z 301.2 (B); 431.2 (C); 271.2 (D) and a 1% (v/v) ethanolic extract of T. foenum-graecum seed spiked with 10 μM vitexin (42 min), 10 μM quercetin (86 min) and 10 μM naringenin (86 min) (E). (B) HPLC–MS analysis in positive ionization mode with a scan range of m/z 150–500 was carried out of a 1% (v/v) ethanolic extract of T. foenum-graecum seed (A) and the extracted ion chromatogram of m/z 433.2 (B); 273.2 (C).

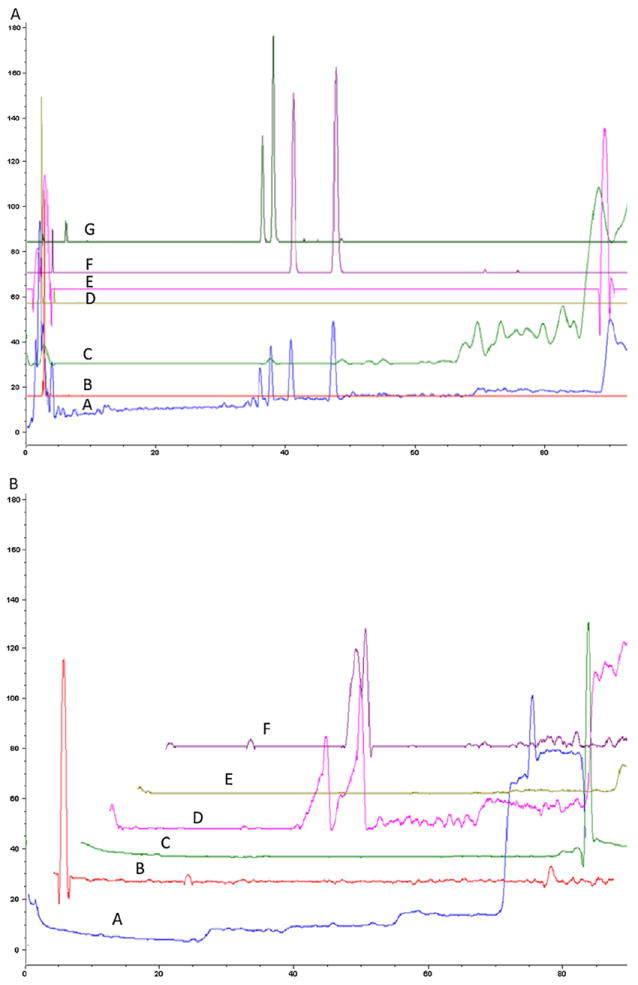

The deacetylation of H3K9Ac by SIRT6-MB was significantly inhibited (>50%, P < 0.05) by 1% TFGExt [24], therefore, a similar concentration of TFGExt was chosen for the ligand fishing experiments for both the SIRT6-MB and the control-MB. The fingerprint of the elution buffer in the m/z range of 100–500, was obtained in both the negative ion mode (Fig. 3A) and positive ion mode (Fig. 3B) for the SIRT6-MB. The identification of vitexin (Fig. 3A(F)/B(D)), naringenin (Fig. 3A(C)) and quercetin (Fig. 3A(E)) was seen in the elution buffer, while, no retention of these inhibitors was observed for the control-MBs. Of interest, in Fig. 3A(F), in addition to vitexin (42 min) and additional peak was identified at 48 min. It is suspected that this peak may correspond to isovitexin, as fenugreek has been reported to be rich in this flavonoid [28]. In addition to these compounds, an additional 14 compounds were identified (Table 1). The major constituents of TFGExt have been previously published [26]. We determined if any of the retained compounds reported in Table 1 matched previously reported compounds and identified orientin (the 8C glucoside of luteolin) as a possible SIRT6 modulator. In order to confirm that the compound was orientin, a standard of orientin was spiked into TFGExt and chromatographed (Fig. 3A(G) (m/z 447.2) and Fig. 4F (m/z 449.2)), the resulting chromatogram demonstrated that orientin had the same retention time and m/z as the identified compound. Of the 18 retained compounds from TFGExt, quercetin, vitexin, naringenin and orientin have been positively identified.

Fig. 3.

(A) Total ion chromatogram of the elution buffer (ammonium acetate buffer [10 mM, pH7.4]) obtained from incubation of a 1% (v/v) ethanolic extract of T. foenum-graecum seed with SIRT6-MB for 15 min in negative ionization mode with a scan range of m/z 150–500 (A) and the extracted ion chromatogram of m/z 267.2 (B); 271.2(C); 401.2 (D); 301.2 (E); 431.2 (F) and 447.2 (G). (B) Total ion chromatogram of the elution buffer (ammonium acetate buffer [10 mM, pH7.4]) obtained from incubation of a 1% (v/v) ethanolic extract of T. foenum-graecum seed with SIRT6-MB for 15 min in positive ionization mode with a scan range of m/z 150–500 (A) and the extracted ion chromatogram of m/z 226.2 (B); 279.2(C); 433.2 (D); 437.2 (E) and 449.2 (F).

Table 1.

HPLC–MS analysis of the elution buffer (ammonium acetate buffer [10 mM, pH7.4]) obtained from incubation of a 1% v/v ethanolic extract of T. foenum-graecum seed with SIRT6-MB for 15 min. The peaks were identified in both negative ionization mode and positive ionization mode with a scan range of m/z 150–1000.

| Positive mode (m/z) | Negative mode (m/z) | |

|---|---|---|

| 150–500 m/z | 174, 226, 235, 279, 433, 437, 449 | 267, 301, 401, 431, 447 |

| 500–1000 m/z | NA | 533, 545, 563, 577, 593, 621, 683 |

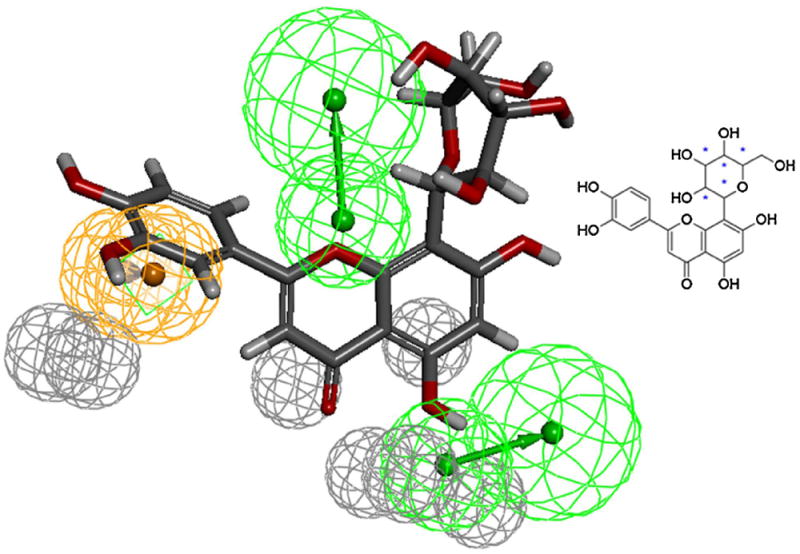

Fig. 4.

Orientin (inset) mapped to the pharmacophore model of the quercetin binding site of SIRT6. Gray spheres indicate the excluded volumes, Green spheres are HBA and the Ring-Aromatic feature is shown in orange color sphere. Common features modeling technique detailed in our previous work [23] was used for creating the pharmacophore model [27]. Discovery Studio (version 3.5; Accelrys, Inc., San Diego, CA) software was used for modeling and analysis. Discovery Studio module Ligand Profiler with default options was used to map Orientin to the model (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of the article.)

Previously, we have generated a refined pharmacophore of the quercetin binding site of SIRT6 [27] and the pharmacophore fit values generated by the model was shown to correlate with the experimental elution time which corresponded to the activity of the SIRT6 protein [23,27]. In order to determine the estimated activity, we used the pharmacophore model to generate the pharmacophore fit value (Fig. 4), and the model predicted that orientin should have a similar binding affinity as luteolin for the SIRT6 protein.

4. Conclusion

A novel affinity-based method utilizing immobilized SIRT6 onto magnetic beads suspended directly into T. foenum graecum seed extract elucidated orientin, and fourteen other compounds, as SIRT6 modulators for the first time. Further investigations are in process to identify the remaining compounds. This method holds potential for other applications and may streamline the development of drug leads from complex chemical matrices.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by funds from the NIA Intramural Research Program (RM), and from the National Cancer Institute/National Institutes of Health contract no. HHSN261200800001E (SR). The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of Health and Human Services, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the U.S. government.

Footnotes

This paper belongs to the “Special issue Chiral Separations 2013”, by R. Moaddel (Guest Editor).

There are no financial conflicts.

References

- 1.Al-Habori M, Raman A. In: Fenugreek: The Genus Trigonella. Petropoulos GA, editor. CRC Press; Boca Raton, FL: 2002. pp. 162–182. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weiss RF. Herbal Medicine, classic ed. Beaconsfield Publishers; Beaconsfield, UK: 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gardner ZE, McGuffin M. American Herbal Products Association. In: The American Herbal Products Association Botanical Safety Handbook. 2. Gardner ZE, McGuffin M, editors. CRC Press; Boca Raton, FL: 2013. pp. 880–882. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mills S, Bone K. Principles and Practice of Phytotherapy: Modern Herbal Medicine. 1. Churchill Livingston; New York: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kumar P, Kale RK, Baquer NZ. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2012;16:18–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mullaicharam AR, Deori G, Uma Maheswari R. Res J Pharm Biol Chem. 2013;4:1304–1313. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yadav M, Lavania A, Tomar R, Prasad GB, Jain S, Yadav H. Appl Biochem Biotechnol. 2010;160:2388–2400. doi: 10.1007/s12010-009-8799-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abdel-Barry JA, Abdel-Hassan IA, Jawad AM, Al-Hakiem MH. East Mediterr Health J. 2000;6:83–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kassaian N, Azadbakht L, Forghani B, Amini M. Int J Vitam Nutr Res. 2009;79:34–39. doi: 10.1024/0300-9831.79.1.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bordia A, Verma SK, Srivastava KC. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 1997;56:379–384. doi: 10.1016/s0952-3278(97)90587-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Suksomboon N, Poolsup N, Boonkaew S, Suthisisang CC. J Ethnopharmacol. 2011;137:1328–1333. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2011.07.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Roberts KT. J Med Food. 2011;14:485–1489. doi: 10.1089/jmf.2011.0002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lu FR, Shen L, Qin Y, Gao L, Li H, Dai Y. Chin J Integr Med. 2008;14:56–60. doi: 10.1007/s11655-007-9005-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Perla V, Jayanty SS. Food Chem. 2013;138:1574–1580. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2012.09.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sauvaire Y, Petit P, Broca C. Diabetes. 1998;47:206–210. doi: 10.2337/diab.47.2.206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Haigis MC, Sinclair DA. Annu Rev Pathol. 2010;5:253–295. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pathol.4.110807.092250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mostoslavsky R, Chua KF, Lombard DB, Pang WW, Fischer MR, Gellon L, Liu P, Mostoslavsky G, Franco S, Murphy MM. Cell. 2006;124:315–329. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.11.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu TF, Vachharajani VT, Yoza BK, McCall CE. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:25758–25769. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.362343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhong L, D’Urso A, Toiber D, Sebastian C, Henry RE, Vadysirisack D, Guimaraes A, Marinelli B, Widstrom JD, Nir T, Clish CB, Vaitheesvaran B, Illiopoulos O, Kurland L, Dor Y, Weissleder R, Shirihai OS, Ellisen LW, Espinosa JM, Mostoslavsky R. Cell. 2010;40:280–293. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.12.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dominy JE, Jr, Lee Y, Jedrychowski MP, Chim H, Jurczak MJ, Camporez JP, Ruan HB, Feldman J, Pierce K, Mostoslavsky R, Denu JM, Clish CB, Yang X, Shulman GI, Gygi SP, Puigserver P. Mol Cell. 2012;48:900–913. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.09.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lang G, Mayhudin NA, Mitova MI, Sun L, Sar SV, Blunt JW, Cole ALJ, Ellis G, Laatsch H, Munro MHG. J Nat Prod. 2008;71:1595–1599. doi: 10.1021/np8002222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lourenço KV, Jiang Z, Zang X, Curcino LCV, Gonçalvez AC, Lucia CC, Bezerra QC, Moaddel R. Talanta. 2013;116:647–652. doi: 10.1016/j.talanta.2013.07.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Singh N, Ravichandran S, Norton DD, Fugmann SD, Moaddel R. Anal Biochem. 2013;436:78–83. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2013.01.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yasuda M, Wilson DR, Fugmann SD, Moaddel R. Anal Chem. 2011;83:7400–7407. doi: 10.1021/ac201403y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Adams J, Tan E. Herbal Manufacturing: How to Make Medicines from Plants. Northern Melbourne Institute of TAFE; Australia: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yilmaz Y, Toldeo RT. J Agric Food Chem. 2004;52:255–260. doi: 10.1021/jf030117h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ravichandran S, Singh N, Donnelly D, Migliore M, Johnson P, Fishwick C, Luke BT, Martin B, Maudsley S, Fugmann S, Moaddel R. J Mol Graphics Modell. 2014;49:38–46. doi: 10.1016/j.jmgm.2014.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chatterjee S, Prasad SV, Sharma A. Food Chem. 2010;119:349–353. [Google Scholar]