Abstract

The increasing incidence and severity of methicillin- and vancomycin-resistant infections during pregnancy prompted further development of telavancin. The understanding of the pharmacokinetics of telavancin during pregnancy is critical to optimize dosing. Due to ethical and safety concerns the study is conducted on the pregnant baboons. A method using solidphase extraction coupled with liquid chromatography-single quadrupole mass spectrometry for the quantitative determination of telavancin in baboon plasma samples was developed and validated. Teicoplanin was used as an internal standard. Telavancin was extracted from baboon plasma samples by using Waters Oasis® MAX 96-Well SPE plate and achieved extraction recovery was > 66% with variation < 12%. Telavancin was separated on Waters Symmetry C18 column with gradient elution. Two SIM channels were monitored at m/z 823 and m/z 586 to achieve quantification with simultaneous confirmation of telavancin identification in baboon plasma samples. The linearity was assessed in the range of 0.188 µg/mL to 75.0 µg/mL, with a correlation coefficient of 0.998. The relative standard deviation of this method was < 11% for within- and between-run assays, and the accuracy ranged between 96% and 114%.

Keywords: Telavancin, LC-ESI-MS, SPE, Baboon plasma

1 Introduction

The appearance of Staphylococcus aureas (S. aureus) resistance strains, known as methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureas (MRSA), has become a significant healthcare problem in patients of all ages and demographics [1]. One group of population that appears to be particularly susceptible to MRSA infections is the pregnant and postpartum patients. S. aureus is a causative agent in approximately 25–50% of cesarean section infectious wound morbidity and puerperal mastitis [2]. During the period between 2000 and 2004, the rate of MRSA infections in pregnant women increased 10-fold [3]. Although vertical and neonatal transmission of MRSA is rare, the consequences to the developing fetus can be severe [4]. Therefore, effective treatment and prompt resolution of maternal infection will certainly benefit the fetus and neonate as well.

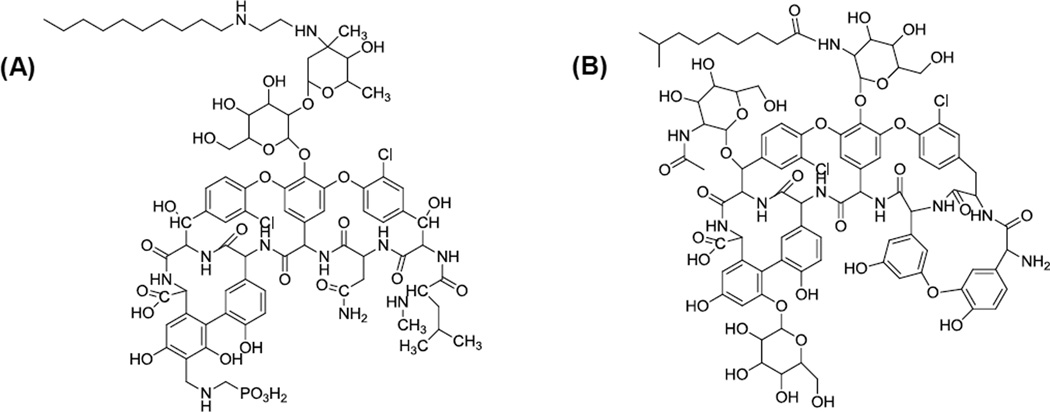

Until recently, vancomycin has been the antibiotic of choice for treatment of infections caused by MRSA. However, the development of vancomycin-resistant strains of Staphylococcus aureus (VRSA) have compromised its use [5] and led to the development of its derivative telavancin (Figure 1) [6]. Telavancin was approved by FDA for treatment of adults with complicated skin infections, including MRSA and vancomycin resistant S. aureus [7]. Telavancin is classified as Pregnancy Category C drug and is not approved for treatment of these infections due to insufficient safety and efficacy data on the pregnant patient and fetal development [6]. However, the increasing incidence and severity of MRSA and VRSA infections during pregnancy, treatment failures, recurrences, and drug resistance prompted further development of telavancin for pregnant patient.

Figure 1.

The chemical structures of (A) telavancin, MW=1756 and (B) teicoplanin (the internal standard), MW=1880.

The current dosing of telavancin during pregnancy is based on its pharmacokinetics (PK) in men and non-pregnant women [8] which does not take into consideration the physiological changes occurring during pregnancy and their effect on PK and efficacy of administered medications [9]. Developing a comprehensive understanding of the PK of telavancin for the treatment of MRSA infections during pregnancy and postpartum will provide the critical data required to optimize dosing, and as a result achieve earlier clearance of infection. Therefore, the goal of the current pre-clinical investigation conducted by the Department of OB & GYN at the University of Texas Medical Branch (UTMB) is to determine the pharmacokinetics (PK) of telavancin in each trimester of pregnancy and postpartum. Due to ethical and safety concerns the PK study is conducted on the pregnant baboons (Papio cynocephalus), which has been validated in our center as an animal model for pregnancy [10].

In the present study, the lowest concentration of telavancin determined in pre-tested baboon plasma following intravenous infusion was approximately 200 ng/ml. Since the molecular weight of telavancin is 1756 Da, the low molarity of the compound at this concentration precluded the use of HPLC-UV. Previously, LC-MS/MS method to achieve the lower limit of quantification (LLOQ) of telavancin at 250 ng/mL in human plasma samples has been briefly described [11–13]. However, these reports cited the method developed by Covance Bioanalytical Services, LLC, Indianapolis, IN, and detailed information of the method is not publically available. Therefore, the aim of current investigation was to develop and validate a LC-MS method for quantitative determination of telavancin in plasma samples from pregnant baboons.

2 Experimental

2.1 Chemicals, reagents and biological samples

Telavancin hydrochloride injection (VIBATIV®, 250 mg/vial) was a generous gift from Theravance, Inc. (South San Francisco, CA). VIBATIV® is a lyophilized powder containing telavancin hydrochloride 250 mg, hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin 2500 mg, mannitol 312.5 mg, sodium hydroxide and hydrochloric acid used in minimal quantities for pH adjustment. Other chemicals and reagents were purchased from the following companies: teicoplanin from Biotang Inc. (Waltham, MA), vancomycin and A4092 from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO); LC-MS grade acetonitrile, methanol, formic acid, ammonium hydroxide, hydrochloric acid from Fisher Scientific (Fair Lawn, NJ).

Blank plasma from six pregnant baboons containing heparin sodium as the anticoagulant was obtained from Southwest National Primate Research Center, Texas Biomedical Research Institute (San Antonio, TX), and stored at −70°C. All animal procedures were performed in accordance with accepted standards of humane animal care and approved by IACUC Southwest Foundation for Biomedical Research at San Antonio, Texas.

2.2 Instrument and analytical conditions

Analysis of telavancin was carried out using an LC-MS instrument consisting of a Waters® 600E multi-solvent delivery system, a Waters 717 auto-sampler, and a Waters EMD 1000 single quadrupole mass spectrometer controlled by Empower™ 2 Data Software (Waters, Milford, MA).

Telavancin was separated at room temperature (22–25°C) on a Waters Symmetry C18 column (150 × 4.6 mm, 5 µm) fitted with a Phenomenex C18 guard column (4 × 3.0 mm). The mobile phase consisted of solvent A: acetonitrile (containing 0.1% formic acid, v/v) and solvent B: water (containing 0.1% formic acid, v/v). The flow rate of mobile phase was 1.0 mL/min and the following gradient: 0–10 min, linear from 12% to 20% A; 10–15 min, linear from 20% to 90% A; 15–20 min, 12% A for re-equilibration of the HPLC column. The post-column eluent was split with a PEEK “T” connector and 250 µL/min of split eluent was directed into the mass spectrometer.

The mass spectrometer was equipped with an electrospray ion source (ESI) operated in positive mode. MS parameters were as follows: capillary voltage = 4.0 kV; source temperature = 140°C; desolvation temperature = 400°C; desolvation gas flow rate = 400 L/h and cone gas flow rate =150 L/h. Three selected ion monitoring (SIM) channels were monitored at: m/z 586 (cone voltage at 20 V) and m/z 823 (cone voltage at 40 V) for telavancin; m/z 316 (cone voltage at 40 V) for teicoplanin (internal standard, IS). The schedule of SIM signal collection was setup as follows: 6–10min for m/z 586 and 832; 11–15min for m/z 316.

2.3 Preparation of working stock solutions, calibration standards and quality control samples

Due to the lack of commercially available reference standard, telavancin injection (VIBATIV®, 250 mg/vial) was used to prepare the working stock solutions for the quantitative analysis. One vial of telavancin injection was dissolved into 25.0 mL deionized water and further diluted with 30% methanol to make the working stock solutions in the range between 0.938 µg/mL and 375 µg/mL. The working stock solutions of teicoplanin (IS) were prepared in the same solvent to achieve the final concentration of 15.4 µg/mL. All stock solutions were stored at 4°C and avoided light.

The calibration standards were prepared by adding 10 µL of telavancin working stock solution into 50 µL blank baboon plasma samples to achieve final concentrations of 0.188, 0.375, 0.750, 1.50, 7.50, 18.8, 37.5, 56.2 and 75.0 µg/mL. Quality control (QC) samples were similarly prepared at high (75.0 µg/mL), medium (37.5 µg/mL), and low concentrations (0.375 µg/mL), as well as samples for the determination of the LLOQ (0.188 µg/mL).

2.4 Sample preparation

Sample preparation was performed using the Oasis® MAX 96-well SPE plate (30 µm, 10mg) operated by the Positive Pressure-96 SPE extraction system (Waters, Milford, MA). The SPE plate was conditioned by 0.5 mL methanol followed by 0.5 mL deionized water. The baboon plasma samples (50 µL), calibration standards or QC samples containing 10 µL of IS working stock solution were pre-mixed with 150 µL of 20% (v/v) NH4OH aqueous solution and then loaded onto the conditioned SPE plate. The SPE plate was washed with 0.5 mL of 5% (v/v) NH4OH aqueous solution followed by 0.5 mL methanol. The eluent of 0.5 mL methanol containing 10% (v/v) formic acid solution was collected and dried under nitrogen stream at 40°C. The dried residues were reconstituted in 200 µL of initial mobile phase. An aliquot of 25 µL of each sample was injected and analyzed by LC-MS system.

2.5 Method validation

This analytical method of telavancin was validated for selectivity, matrix effect, extraction recovery, precision, accuracy, sensitivity, linearity and stability within the guidelines established by the FDA for bioanalytical method validation [14].

The selectivity of the method was evaluated by analyzing blank baboon plasma samples obtained from six pregnant baboons. The SIM chromatograms of the blank samples were compared to LLOQ samples with telavancin. The peak area of interference substances in blank samples co-eluting with telavancin should be < 5% of the peak area of telavancin at LLOQ concentration levels.

The matrix effect of telavancin and IS was evaluated quantitatively by calculating the Matrix Factor, which is defined as the ratio of the analyte peak area in post-extraction samples to the analyte peak area in pure standards [15]. The Matrix Factors of telavancin were investigated at low, medium and high concentrations in blank baboon plasma samples. The variability of the Matrix Factor, as measured by the relative standard deviation (RSD) should be <15% [15]. The extraction recovery of telavancin from baboon plasma samples was evaluated with the peak area of telavancin in QC samples versus the peak area of telavancin in the post-extracted samples at low, medium and high concentration levels.

Within-run and between-run accuracy and precision of telavancin in blank baboon plasma samples were evaluated by the analysis of six replicates of each QC sample at high, medium, low and LLOQ concentration levels. For the Within-run accuracy and precision, QC samples were analyzed using a calibration curve prepared on the same analytical run; for the between-run accuracy and precision, the QC samples were analyzed on three different analytical runs. The RSD for each concentration level should be <15%, except for LLOQ, which should be <20%. Accuracy of the method was evaluated as [mean obtained concentration/nominal concentration] × 100%. The accuracy is expected to be within 15% of the nominal concentration, except for the LLOQ, which should be within 20% [14].

To evaluate the linearity of the method, nine calibration standards of telavancin with blank sample (blank baboon plasma spiked with IS) and double blank sample (blank baboon plasma processed without telavancin or IS) were analyzed in triplicate. The calibration curve was fitted using weighted least-squares linear regression of the internal ratio (peak area of the analyte/peak area of the IS) versus concentration. The weighting factor of the calibration curve was selected according to the percentage of relative error for each calibration standard samples [16]. The correlation coefficient (r) >0.99 is acceptable for all calibration curves.

The stability of telavancin in spiked blank baboon plasma samples was investigated by analyzing triplicate QC samples at high and low concentrations. For freeze-thaw stability, unprocessed QC samples were stored at −70°C for 24 h, thawed at room temperature (22–25°C), and then refrozen at −70°C for 24 h. Samples were analyzed after three freeze-thaw cycles. For bench-top stability and long-term stability investigations, the unprocessed QC samples were kept at room temperature (22–25°C) for 4 h and at −70°C for 35 days, respectively. Thereafter, the QC samples were processed and analyzed. The concentration of telavancin was calculated using a newly prepared calibration curve.

2.6 Method application and incurred sample reanalysis

This validated method was applied to determine the concentration of telavancin in pregnant baboon plasma samples following i.v. infusion. Plasma was separated and kept frozen at −70 °C until analyzed. QC samples were prepared at low, medium and high concentration levels and assayed along with the baboon plasma samples in each run. The accuracy of QC samples (at least 67% of total number of QCs) should be within 15% of their respective nominal concentration values.

Incurred sample reanalysis (ISR) was applied to confirm the reproducibility of the method and the reliability of the reported telavancin concentration in baboon plasma samples. The number of ISR samples should be ≥ 7% of the study samples, and the concentration of telavancin in ISR samples should adequately cover the PK profile. The difference between the original concentration and the repeated concentration was evaluated as [(Repeated concentration−Original concentration)/Mean concentration] × 100%. The difference of at least 67% of ISR samples should be <20% [14].

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Mass spectrometric conditions

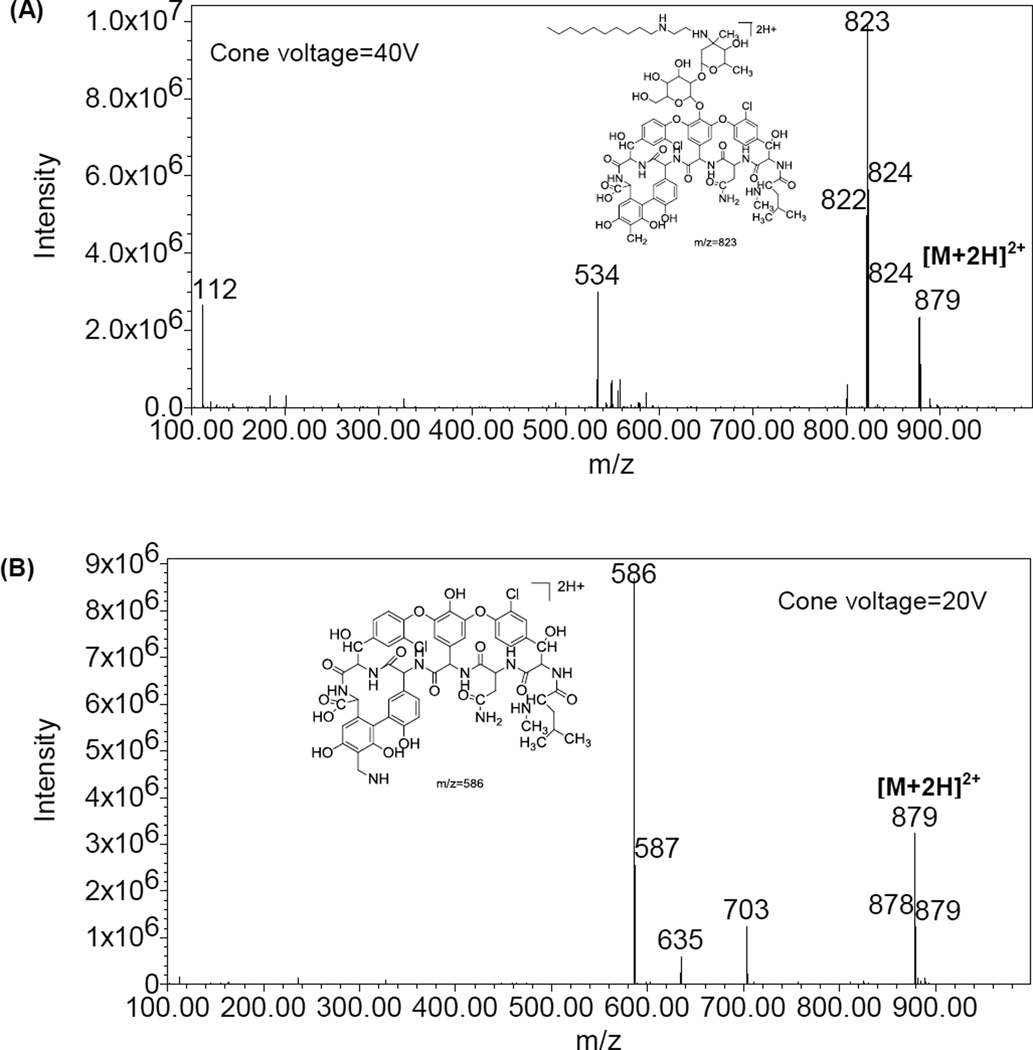

The ionization of telavancin with the ESI interface in both positive and negative ion mode was investigated. The positive ion mode was chosen for analysis of telavancin because of higher sensitivity of all fragment ions than that in the negative ion mode. The doubly charged quasi-molecular ion [M+2H]2+ of telavancin was observed at m/z 879 (Figure 2). This phenomenon was commonly found in lipoglycopeptide compounds, such as vancomycin and teicoplanin [17, 18], because of multiple acidic and basic ionizable groups in these molecules.

Figure 2.

Full-scan positive ionization electrospray mass spectra and the proposed fragmentation pattern of telavancin at (A) a cone voltage of 40 V and (B) a cone voltage at 20 V.

As shown in figure2A and 2B, the doubly charged ion at m/z 586 was the major fragmentation ion at cone voltage of 20 V, whereas the doubly charged ion at m/z 823 was the major fragmentation ion when the cone voltage was increased to 40 V. Both fragmentation ions revealed sufficient sensitivity of telavancin and clean baseline in the blank baboon plasma samples. Single quadrupole mass spectrometer has less selectivity than tandem mass spectrometer, and is usually considered unworkable with complicated matrices due to insufficient selectivity of analyte. However, this disadvantage was overcome in this case by achieving sufficient LC separation of analyte from interference peak and monitoring multiple SIM channels [19]. SIM channels were monitored at m/z 823 and m/z 586 to achieve quantification with simultaneous confirmation of telavancin identification in baboon plasma samples.

The MS conditions of teicoplanin (IS) were similar to the MS conditions of telavancin. The full scan of teicoplanin is shown in Supplementary Figure S1, and high abundance fragmentation ion at m/z 316 was chosen as the SIM channel.

3.2 LC conditions and IS selection

The chromatographic conditions including buffer composition and pH of mobile phase were modified and optimized for peak resolution, retention time and symmetry of analyte peak. Acetonitrile was chosen as organic modifiers because it enabled good selectivity and peak symmetry of telavancin in baboon plasma samples. The aqueous solution was tested using ammonium acetate buffer (pH=8.0 and pH=5.0), 0.1% (v/v) formic acid and 0.1% (v/v) acetic acid solution. A severe tailing peak of telavancin was observed under the ammonium acetate buffer conditions, whereas formic acid and acetic acid conditions showed better peak symmetry and sufficient chromatographic separation of telavancin from its co-eluted interfering peaks in baboon plasma samples. Considering higher baseline noise of acetic acid on the SIM channel at m/z 316, formic acid was selected as pH additive in mobile phase.

Three commercial analogues of telavancin: teicoplanin (Figure 1 B), vacomycin, and A4092 were screened for internal standard selection. Vacomycin co-eluted with unretained endogenous substances in baboon plasma samples under the optimized LC conditions. In contrast, A4092 and teicoplanin showed stronger retention on LC column than that of telavancin. Considering an interference peak of A4092 in baboon plasma samples, teicoplanin was selected as internal standard. Ideally, the internal standard should have a similar retention time to that of its analyte. Therefore, the mobile phase with a sharp linear gradient elution from 10 to 15min (20% to 90% acetonitrile in 5min) was applied to achieve a retention time of teicoplanin as close as possible to telavancin.

The short length HPLC column (Waters Symmetry C18, 75 × 4.6 mm, 3.5 µm) and high flow rate of mobile phase were tested for reducing the chromatographic time. Telavancin could not be sufficiently separated from the interference peak on the 75 mm length HPLC column. High flow rate of mobile phase (1.5 mL/min) was tested on the 150 mm length HPLC column (Waters Symmetry C18, 150 × 4.6 mm, 5 µm). However, the chromatographic time was not significantly reduced, and the pressure of HPLC system was significantly increased. The flow rate of mobile phase at 0.20 mL/min was tested on the narrow-bore HPLC column (Waters Symmetry C18, 100 × 2.1 mm, 3.5 µm) for reducing the solvent consumption. However, the pressure of HPLC system and retention time of teicoplanin was unstable under the low flow rate condition, probably due to the sharp slope gradient for the elution of teicoplanin (IS). Therefore, the Waters Symmetry C18 HPLC column (150× 4.6 mm, 5 µm) was selected for the analysis of telavancin, and the flow rate was setup at 1.0 mL/min.

3.3 Sample preparation

Extraction methods of protein precipitation, liquid-liquid extraction (LLE) and solid phase extraction (SPE) were screened for the preparation of baboon plasma samples. The protein precipitation of baboon plasma by adding methanol, acetonitrile or 20% (w/v) trichloroacetate aqueous solution resulted in severe ion suppression of telavancin in baboon plasma samples. For the optimization of the LLE method, the organic solvents and pH additives were screened as follows: ethyl acetate, dichloromethane, hexane, HCl and NH4OH. Due to high polarity (logP=0.6) [27] and multiply pKa values [20], telavancin cannot be extracted efficiently by organic solvent under acidic or alkaline conditions. The SPE columns with different types of extraction sorbents, such as Waters Oasis HLB (reversed-phase), MCX (mix-mode cation exchange) and MAX (mix-mode anion exchange), were screened for extraction of telavancin in baboon plasma samples. Due to the ion suppression effect on telavancin of Waters Oasis HLB extraction method and the low extraction recovery (<50%) of Waters Oasis MCX, the Waters Oasis MAX was selected to extract telavancin from baboon plasma samples.

3.4 Method validation

3.4.1 Selectivity and matrix effect

The selectivity of the method was achieved by comparing SIM chromatograms of six different blank (non-exposed) baboon plasma samples to LLOQ samples of telavancin. Figure 3 shows the following: typical SIM chromatograms of blank baboon plasma samples, blank baboon plasma samples spiked with telavancin (0.188 µg/mL, LLOQ) and IS, and plasma sample obtained from pregnant baboon after administration of telavancin. The retention time of telavancin and IS were 8.7 min and 13.6 min, respectively. No significant peaks were found at the retention times of telavancin and IS in blank plasma samples.

Figure 3.

Selected ion monitoring (SIM) chromatograms for the determination of telavancin in baboon plasma: (A) chromatogram of a blank plasma sample; (B) chromatogram of a blank plasma sample spiked with telavancin (0.188 µg/mL, LLOQ) and IS; (C) plasma sample of pregnant baboon following intravenous infusion administration of a trelavancin dose of 10 mg.

3.4.2 Matrix effect and extraction recovery

The Matrix Factor of telavancin in baboon plasma at the low, medium and high concentration levels ranged between 110% and 103%, with RSD < 7%. The Matrix factor of IS was 96%, with RSD < 5%. These results indicate that the matrix effect on telavancin and IS in baboon plasma played a minor role.

The extraction recovery of telavancin from baboon plasma ranged between 66% and 76% with variation < 13% at low, medium and high concentration levels. The extraction recovery for IS was 82% with variation < 7%. The data demonstrated that the SPE method for extraction of telavancin and IS from baboon plasma samples was stable and efficient.

3.4.3 Calibration curve and LLOQ

Calibration curve of telavancin in baboon plasma samples was constructed by the internal standard method and fit by using weighted (1/x) least-squares linear regression analysis of internal ratio versus concentration. As shown in table 1, SIM channels of telavancin at m/z 823 and m/z 586 exhibited good linear regressions (r2=0.998) in the concentration range from 0.188 to 75.0 µg/mL in baboon plasma samples. The lack of fit test of the linearity regression between the concentration and the internal ratio was not significant using F-test at α=0.05 levels.

Table 1.

Calibration curves of telavancin monitored at m/z 823 and m/z 586 in baboon plasma samples.

| SIM channels | Regression equationa | Weighting factor |

r2 | F-testb | Linear range (µg/mL) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F | p-value | |||||

| m/z 823 | y=−0.023(±0.011)+0.364(±0.003)x | 1/x | 0.998 | 0.43 | 0.878 | 0.188–75.0 |

| m/z 586 | y=−0.011(±0.010)+0.309(±0.002)x | 1/x | 0.998 | 0.24 | 0.973 | |

: In the regression equation y = b + ax, x refers to the concentration (µg/mL) of telavancin in baboon plasma samples, and y refers to the peak area ratio of telavancin versus the IS. The slope and intercept of the regression equation was presented as mean (±SE).

: F-test for lack-of-fit.

LLOQ is defined as the lowest concentration that can be measured with acceptable accuracy and precision. Although the concentration of telavancin < 0.188 µg/mL can be tested in baboon plasma with signal-to-noise ratio (S/N) >5:1, the non-linearity of calibration curve was observed due to the broad calibration range, and the accuracy at low concentrations were unacceptable. Additionally, since the concentrations of telavancin in all pre-tested baboon plasma samples were never below 0.188 µg/mL, the LLOQ was set at 0.188 µg/mL. As shown in table 2, the within- and between-run accuracy values at the LLOQ (0.188 µg/mL) were in the range of 114% to 99% with precision < 7%, meeting the requirement of FDA guidance.

Table 2.

Within-run and between-run precision and accuracy of telavancin monitored at m/z 823 and m/z 586 in baboon plasma samples.

| Within-run (n=6) | Between-run (n=3) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SIM channels |

Nominal concentration (µg/mL) |

Mean obtained concentration (µg/mL) |

Mean accuracya (%) |

Precision (RSD, %) |

Mean obtained concentration (µg/mL) |

Mean accuracya (%) |

Precision (RSD, %) |

| m/z 823 | 0.188 | 0.213 | 114 | 5.4 | 0.198 | 106 | 6.9 |

| 0.375 | 0.358 | 96 | 4.6 | 0.357 | 95 | 0.6 | |

| 37.5 | 37.0 | 99 | 7.4 | 37.0 | 99 | 7.6 | |

| 75.0 | 75.2 | 100 | 3.7 | 75.1 | 100 | 2.8 | |

| m/z 586 | 0.188 | 0.199 | 106 | 4.6 | 0.185 | 99 | 6.4 |

| 0.375 | 0.360 | 96 | 7.0 | 0.361 | 96 | 0.5 | |

| 37.5 | 37.6 | 100 | 7.5 | 38.4 | 102 | 10.7 | |

| 75.0 | 74.7 | 99 | 4.1 | 74.1 | 99 | 3.4 | |

: accuracy (%) = (mean obtained concentration/nominal concentration)×100%.

3.4.4 Accuracy and precision

The precision was presented as the RSD and the accuracy was calculated as the recovery of the nominal concentration. As shown in Table 2, the within-run accuracy for telavancin monitored at m/z 823 and m/z 586 ranged between 96% and 100% with precision < 8%, and the between-run accuracy ranged between 95% and 102% with precision < 11%. These results demonstrate that the SIM at m/z 823 and m/z 586 can both achieve reproducible quantitative determination of telavancin in baboon plasma samples. However at LLOQ, SIM at m/z 586 was more accurate than SIM at m/z 823 (106% vs. 114% in within-run and 99% vs. 106% in between-run analysis). Therefore, the SIM at m/z 586 was selected as quantification channel, and the SIM channel at m/z 823 was included as qualification channel for the confirmation of identity of telavancin.

3.4.5 Stability of telavancin in spiked baboon plasma samples

The stability of telavancin in baboon plasma was investigated under a variety of storage and handling conditions which exceeded the routine sample preparation and storage time. The recovery of telavancin in the freeze-thaw, bench-top and long-term stability samples ranged between 93.0% and 103.7% with precision < 8%, indicating that telavancin is stable in the above storage conditions.

3.4 Method application and incurred sample reanalysis

To date, a total of 56 baboon plasma and 18 QC samples were tested with this validated analytical method. The concentration of telavancin in baboon plasma samples ranged from 0.223 and 82.8 µg/mL. In two baboon plasma samples, the concentration of telavancin was out of the calibration range. These two samples were diluted 2 times with blank baboon plasma and reanalyzed with validated method. The accuracy of 16 QCs were within 15% of their respective nominal concentration values, whereas the accuracy of only 2 QCs exceeded 15% but was not more than 18%.

A total of 10 ISR samples were selected and reanalyzed. The differences of telavancin concentration in original test results and ISR test results were <15% in all ISR samples. These results confirmed the reproducibility of the validated method and the reliability of reported telavancin concentration in baboon plasma.

4. Conclusion

This is the first report of a sensitive and reliable solid-phase extraction coupled with LC-ESI-MS method for quantitative determination of telavancin in baboon plasma samples. Two SIM channels were monitored at m/z 823 and m/z 586 to achieve quantification with simultaneous confirmation of identity of telavancin in baboon plasma samples. The method had an LLOQ at 0.188 µg/mL with a linear calibration range of 0.188–75.0 µg/mL using 50 µL of baboon plasma sample.

The major disadvantage of this method is the long chromatographic time of each injection because of the strong retention of teicoplanin (internal standard) on the HPLC column. The application of ultra performance liquid chromatography (UPLC) technique or using stable isotope labeled telavancin as internal standard could potentially shorten the chromatographic time to meet the requirements of high-throughput analysis.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figure S1, Full-scan electrospray mass spectra of the teicoplanin (the internal standard) at cone voltage of 40 V.

Highlight.

SPE coupled with LC-ESI-MS method was developed and validated in baboon plasma.

Two SIM channels monitored for identification and quantification of telavancin.

Telavancin linearity assessed between 0.188 and 75.0 µg/ml.

Acknowledgement

This work was supported by grant U10HD047891 from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD), Obstetric Pharmacology Research Unit Network (OPRU) G. D.V. Hankins P.I. E. Rytting is supported by a research career development award (K12HD052023: Building Interdisciplinary Research Careers in Women’s Health Program, BIRCWH) from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), the NICHD, and the Office of the Director (OD), National Institutes of Health. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIAID, NICHD, OD, or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Kriebs JM. Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus Infection in the Obstetric Setting. J. Midwifery & Women’s Health. 2008;53:247–250. doi: 10.1016/j.jmwh.2008.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sweet LR, Gibbs RS. Infectious diseases of the female genital tract. 4th ed. Philadelphia (PA): Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2001. Clinical microbiology of the female genital tract; pp. 3–12. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Laibl VR, Sheffield JS, Roberts S, McIntire DD, Trevino S, Wendel GD. Clinical presentation of community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in pregnancy. Obstet. Gynecol. 2005;106:461–465. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000175142.79347.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bratu S, Antonella E, Robert K, Elizabeth C, Monica G, Robert Y, et al. Community-associated methicillan-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in hospital nursery and maternity units. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2005;11:808–813. doi: 10.3201/eid1106.040885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Howden BP, Ward PB, Charles PGP, Korman TM, Afuller F, Cros PD, et al. Treatment Outcomes for Serious Infections Caused by Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus with Reduced Vancomycin Susceptibility. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2004;38:521–528. doi: 10.1086/381202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Plotkin P, Patel K, Uminski A, Marzella N. Telavancin (Vibativ), a new option for the treatment of gram-positive infections. Drug Forecast. 2011;36:127–138. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.European Medicines Agency. Assessment report: Vibativ. 2009 http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/EPAR_-_Public_assessment_report/human/001240/WC500115363.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smith WJ, Drew RH. Telavancin: a new lipoglycopeptide for gram-positive infections. Drugs. Today. 2009;45:159–173. doi: 10.1358/dot.2009.45.3.1343792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Loebstein R, Lalkin A, Koren G. Pharmacokinetic changes during pregnancy and their clinical relevance. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 1997;33:328–343. doi: 10.2165/00003088-199733050-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zharikova OL, Ravindran S, Nanovskaya TN, Hill RA, Hankins GDV, Ahmed MS. Kinetics of glyburide metabolism by hepatic and placental microsomes of human and baboon. Biochem Pharmacol. 2007;73:201–209. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2007.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rashid M, Weintraub A, Nord CE. Effect of telavancin on human intestinal microflora. Int. J. Antimicrob. Ag. 2011;38:474–479. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2011.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goldberg MR, Wong SL, Shaw JP, Kitt MM, Barriere SL. Lack of effect of moderate hepatic impairment on the pharmacokinetics of telavancin. Pharmacotherapy. 2010;30:35–42. doi: 10.1592/phco.30.1.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gotfried MH, Shaw JP, Bento BM, Krause M, Goldberg MR, Kitt MM, Barriere SL. Intrapulmonary distribution of intravenous telavancin in healthy subjects and effect of pulmonary surfactant on in viro activities of tealvancin and other antibiotics. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2008;52:92–97. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00875-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Food and Drug Administration. Guidance for Industry: Bio-analytical Method Validation. Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. 2013 Sep; http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Guidances/ucm064964.htm.

- 15.Viswanathan CT, Bansal S, Booth B, DeStefano AJ, Rose MK, Sails TJ, et al. Workshop/Conference Report-Quantitative bioanalytical methods validation and implementation: Best practices for chromatographic and ligand biding assays. AAPS J. 2007;9:E30–E42. doi: 10.1007/s11095-007-9291-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Almdida AM, Castel-Branco MM, Falcao AC. Linear regression for calibration lines revised: weighting schemes for bioanalytical methods. J.Chromatogr. B. 2002;774:215–222. doi: 10.1016/s1570-0232(02)00244-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nobuhito S, Makoto I, Yarasani VRP, Weihua G, Yukako Y, Kanji T. Highly sensitive quantification of vancomycin in plasma samples using liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry and oral bioavailabiity in rats. J.Chromatogr. B. 2003;789:211–218. doi: 10.1016/s1570-0232(03)00068-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cass RT, Villa JS, Karr DE, Schmidt DE. Rapid bioanalysis of vancomycin in serum and urine by high-performance liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry using on-line sample extraction and parallel analytical columns. Rapid. Commun. Mass Spectrom. 2001;15:406–412. doi: 10.1002/rcm.246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Crellin KC, Sible E, Antwerp JV. Quantification and confirmation of identity of analytes in various matrices with in-source collision-induced dissociation on a single quadrupole mass spectrometer. Int. J. Mass Spectrom. 2003;222:281–311. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barcia-Macay M, Mouaden F, Mingeot-Leclercq MP, Tulkens PM, Van Bambeke F. Cellular pharmacokinetics of telavancin, a novel lipoglycopeptide antibiotic, and analysis of lysosomal changes in cultured eukaryotic cells (J774 mouse macrophages and rat embryonic fibroblasts) J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2008;61:1288–1294. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkn120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figure S1, Full-scan electrospray mass spectra of the teicoplanin (the internal standard) at cone voltage of 40 V.