Abstract

Background

More than 20% of women undergo induction of labour in some countries. The different methods used to induce labour have been the focus of previous reviews, but the setting in which induction takes place (hospital versus outpatient settings) may have implications for maternal satisfaction and costs. It is not known whether some methods of induction that are effective and safe in hospital are suitable in outpatient settings.

Objectives

To assess the effects on outcomes for mothers and babies of induction of labour for women managed as outpatients versus inpatients.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group’s Trials Register (December 2008). We updated this search on 24 February 2012 and added the results to the awaiting classification section.

Selection criteria

Published and unpublished randomised and quasi-randomised trials in which inpatient and outpatient methods of cervical ripening or induction of labour have been compared.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently assessed trial reports for inclusion. Two review authors carried out data extraction and assessment of risk of bias independently.

Main results

We included three trials, with a combined total of 612 women in the review; each examined a different method of induction and we were unable to pool the results from trials.

Vaginal PGE2 (One study including 201 women). There were no differences between women managed as out- versus inpatients for most review outcomes. Women in the outpatient group were more likely to have instrumental deliveries (risk ratio (RR) 1.74; 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.03 to 2.93). The overall length of hospital stay was similar in the two groups.

Controlled release PGE2 10mg (one study including 300 women). There was no evidence of differences between groups for most review outcomes, including success of induction. During the induction period itself, women in the outpatient group were more likely to report high levels of satisfaction with their care (satisfaction rated seven or more on a nine-point scale RR 1.42; 95% CI 1.11 to 1.81), but satisfaction scores measured postnatally were similar in the two groups.

Foley catheter (one study including 111 women). There was no evidence of differences between groups for caesarean section rates, total induction time and the numbers of babies admitted to neonatal intensive care.

Authors’ conclusions

The data available to evaluate the efficacy or potential hazards of outpatient induction are limited. It is, therefore, not yet possible to determine whether induction of labour is effective and safe in outpatient settings.

[Note: The four citations in the awaiting classification section of the review may alter the conclusions of the review once assessed.]

Medical Subject Headings (MeSH): *Cervical Ripening; *Hospitalization; Ambulatory Care [*methods]; Catheterization; Dinoprostone; Infant, Newborn; Labor, Induced [*methods]; Length of Stay; Oxytocics; Patient Satisfaction; Pregnancy Outcome; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic

MeSH check words: Female, Humans, Pregnancy

BACKGROUND

Multiple interventions are available for cervical ripening and induction of labour at term (Kelly 2001).

The method used, and indications for induction of labour, have been the main focus of previous trials, systematic reviews and guidelines, but there has been less published work focusing on the place of induction of labour. This is an important issue, as the number of women undergoing labour induction seems to be increasing; in England as a whole rates are above 20%, and some units report more than 25% of women being induced (NHS 2007).

The ideal agent for induction of labour would achieve cervical ripening followed by ‘spontaneous’ onset of labour without causing uterine hyperstimulation (Calder 1998). Currently most commonly used induction agents result in significant uterine activity, requiring close monitoring of mother and baby within a hospital environment. Some induction methods, such as intravenous syntocinon infusions, will only be suitable for use in an inpatient setting. Induction of labour in an outpatient setting is therefore, restricted to low-risk circumstances when cervical ripening and labour induction is carried out without an ongoing requirement for continuous or frequent maternal or fetal monitoring. The use of outpatient induction of labour attempts to balance potential improvements in maternal satisfaction, convenience, reduced length of hospitalisation and lower cost, against those of safety (both maternal and fetal). For the purpose of this review, outpatient settings include home and all other facilities (healthcare or otherwise) that are physically distant from the actual place of birth and require transport to hospital in case of complications. In most instances an outpatient induction will include an initial hospital assessment, including administration of the ripening or induction agent.

OBJECTIVES

The primary objective of this review is to assess the effects on maternal and neonatal outcomes of cervical ripening or third trimester induction of labour for women managed as outpatients compared to inpatient management.

A secondary objective of the review is to determine whether the effects on maternal and neonatal outcomes are influenced by predefined clinical subgroups including the effect of parity, membrane status (intact or ruptured) and cervical status (unfavourable, favourable or undefined).

This review does not attempt to compare the relative effects of different methods of induction of labour on maternal and neonatal outcomes within an outpatient setting. This is the topic of a separate review (Kelly 2009).

METHODS

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

All published and unpublished randomised trials, in which inpatient and outpatient methods of cervical ripening or induction of labour are compared. The trials include some form of random allocation to either group; and they report one or more of the prestated outcomes. In updates of the review we plan to include cluster-randomised trials if they are otherwise eligible.

Types of participants

Pregnant women with a viable fetus suitable for cervical ripening or induction of labour at or near term (greater than 35 weeks) in an outpatient setting.

Types of interventions

Outpatient cervical ripening or induction of labour with pharmacological agents or mechanical methods. Outpatient ripening is defined as any cervical ripening or induction of labour intervention (with the exception of membrane sweeping) that can be carried out at home or within community healthcare settings. It also includes a package of care initially provided in hospital (fetal monitoring, drug administration) after which the patient is allowed home until later review or until admission in labour.

Types of outcome measures

Clinically relevant outcomes for trials of methods of cervical ripening and labour induction have been prespecified by two authors of labour induction reviews (Justus Hofmeyr and Zarko Alfirevic) (Hofmeyr 2000). Most of these outcomes relevant to both inpatient and outpatient settings are used in this review.

In addition, an attempt has been made to use relevant outcome measures to quantify any cost effectiveness benefits of outpatient ripening.

Primary outcomes

Failure to achieve spontaneous vaginal delivery.

Additional induction agents required.

Length of hospital stay.

Use of emergency services.

Mother not satisfied.

Caregiver not satisfied.

Serious neonatal morbidity or perinatal death (e.g. seizures, birth asphyxia defined by trialists, neonatal encephalopathy, disability in childhood).

Serious maternal morbidity or death (e.g. uterine rupture, admission to intensive care unit, septicaemia).

Secondary outcomes

Outcomes related to measures of effectiveness, complications and satisfaction.

Measures of effectiveness

Vaginal delivery not achieved within 24/48/72 hours.

Randomisation to delivery interval.

Oxytocin augmentation.

Pain relief requirements (epidural, opioids).

Complications

Uterine hyperstimulation.

Instrumental vaginal delivery.

Caesarean section.

Apgar score less than seven at five minutes.

Neonatal intensive care unit admission.

Perinatal death.

Uterine rupture.

Postpartum haemorrhage (as defined by the trial authors).

Serious maternal complications (e.g. intensive care unit admission, septicaemia).

Where formal economic evaluation is lacking, we will attempt to describe potential cost savings and the impact of interventions used within an outpatient setting. Where possible these estimates will involve using some measures of effectiveness and complications in combination with estimates of healthcare provision.

Detailed definitions for outcomes

Perinatal and maternal morbidity and mortality are composite outcomes. This is not an ideal solution because some components are clearly less severe than others. It is possible for one intervention to cause more deaths but less severe morbidity. However, in the context of labour induction at term, this is unlikely. All these events will be rare, and a modest change in their incidence will be easier to detect if composite outcomes are presented. The incidence of individual components will be explored as secondary outcomes (see above).

‘Uterine rupture’ includes all clinically significant ruptures of unscarred or scarred uteri. Trivial scar dehiscence noted incidentally at the time of surgery is excluded.

The terminology of uterine hyperstimulation is problematic (Curtis 1987). In the reviews, the term ‘uterine hyperstimulation’ is defined as uterine tachysystole (more than five contractions per 10 minutes for at least 20 minutes) and uterine hypersystole/hypertonus (a contraction lasting at least two minutes).

‘Uterine hyperstimulation with fetal heart rate (FHR) changes’ is usually defined as uterine hyperstimulation syndrome (tachysystole or hypersystole with FHR changes such as persistent decelerations, tachycardia or decreased short-term variability). However, due to varied reporting, there is the possibility of subjective bias in the interpretation of these outcomes. Also, it is not always clear from the trials if these outcomes are reported in a mutually exclusive manner. More importantly, continuous monitoring is unlikely in an outpatient setting. Therefore, there is a high risk of biased reporting of uterine hyperstimulation (with or without FHR changes). It is possible that bias will favour the outpatient setting (i.e. by failure to recognise mild forms of hyperstimulation without continuous monitoring). On the other hand, clinicians who favour inpatient induction may, in the absence of continuous monitoring, label any maternal description of painful, frequent uterine contractions as hyperstimulation. Therefore, in the absence of blinding, hyperstimulation and other ‘soft’ outcomes should be interpreted with extreme caution.

While we sought data on all of the outcomes listed above, we have documented only those with data in the analysis tables. We have included outcomes in the analysis if reasonable measures were taken to minimise observer bias, and data were available according to original treatment allocation.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We contacted the Trials Search Co-ordinator to search the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group’s Trials Register (December 2008). We updated this search on 24 February 2012 and added the results to Studies awaiting classification.

The Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group’s Trials Register is maintained by the Trials Search Co-ordinator and contains trials identified from:

quarterly searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL);

weekly searches of MEDLINE;

weekly searches of EMBASE;

handsearches of 30 journals and the proceedings of major conferences;

weekly current awareness alerts for a further 44 journals plus monthly BioMed Central email alerts.

Details of the search strategies for CENTRAL, MEDLINE and EMBASE, the list of handsearched journals and conference proceedings, and the list of journals reviewed via the current awareness service can be found in the ‘Specialized Register’ section within the editorial information about the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group.

Trials identified through the searching activities described above are each assigned to a review topic (or topics). The Trials Search Co-ordinator searches the register for each review using the topic list rather than keywords

We did not apply any language restrictions.

Data collection and analysis

The review authors worked independently to assess trials for inclusion and for methodological quality. We resolved differences in interpretation by discussion.

Selection of studies

Two review authors (A Kelly and T Dowswell) independently assessed for inclusion all the potential studies identified as a result of the search strategy. We resolved any disagreement through discussion, or if required we consulted the third author.

Data extraction and management

We designed a form to extract data. At least two review authors extracted the data using the agreed form. We resolved discrepancies through discussion. We entered data into Review Manager software (RevMan 2008) and checked for accuracy.

When information on study design or outcomes was unclear, we attempted to contact authors of the original reports to provide further details.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors independently assessed risk of bias for each study using the criteria outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2008). We resolved any disagreement by discussion or by involving a third assessor.

(1) Sequence generation (checking for possible selection bias)

We have described for each included study the methods used to generate the allocation sequence in sufficient detail to allow an assessment of whether it should produce comparable groups.

We assessed the methods as:

adequate (e.g. random number table; computer random number generator);

inadequate (odd or even date of birth; hospital or clinic record number); or,

unclear.

(2) Allocation concealment (checking for possible selection bias)

We have described for each included study the method used to conceal the allocation sequence in sufficient detail and determine whether intervention allocation could have been foreseen in advance of, or during, recruitment.

We assessed the methods as:

adequate (e.g. telephone or central randomisation; consecutively numbered sealed opaque envelopes);

inadequate (open random allocation; unsealed or non opaque envelopes; alternation; date of birth);

unclear.

(3) Blinding (checking for possible performance bias)

When comparing induction of labour in different settings blinding women and clinical staff is not usually possible (although it may be feasible to blind outcome assessors for some outcomes). We did not formally assess blinding (or lack of it). Studies have been judged as being at lower risk of bias where we considered that lack of blinding was unlikely to affect results.

(4) Incomplete outcome data (checking for possible attrition bias through withdrawals, dropouts, protocol deviations)

We have described for each included study the completeness of data for each main outcome, including attrition and exclusions from the analysis. We have noted whether attrition and exclusions were reported, the numbers (compared with the total randomised participants), reasons for attrition/exclusion where reported, and any re-inclusions in analyses which we have undertaken.

We have assessed the methods as:

adequate (e.g. where there are no missing data or relatively low levels of attrition (less than 20%) and reasons for missing data are balanced across groups);

inadequate (e.g. where there are higher levels of missing data or where missing data are not balanced across groups);

unclear (e.g. where there is insufficient reporting of attrition or exclusions to permit a judgement to be made).

(5) Selective reporting bias

We have described for each included study how the possibility of selective outcome reporting bias was examined by us and what we found.

We have assessed the methods as:

adequate (where it is clear that all of the study’s prespecified outcomes and all expected outcomes of interest to the review have been reported);

inadequate (where not all the study’s prespecified outcomes have been reported; one or more reported primary outcomes were not prespecified; outcomes of interest are reported incompletely and so cannot be used; or, study fails to include results of a key outcome that would have been expected to have been reported);

unclear.

(6) Other sources of bias

We have noted for each included study any important concerns we have about other possible sources of bias. For example, any potential sources of bias associated with a particular study design.

Measures of treatment effect

We have carried out statistical analysis using the Review Manager software (RevMan 2008). As part of analysis we had planned to pool results from trials but as the three included studied examined different interventions we have examined them separately. In updates of the review we will pool data using the methods set out in Appendix 1.

RESULTS

Description of studies

See: Characteristics of included studies; Characteristics of studies awaiting classification; Characteristics of ongoing studies.

The search strategy identified four studies for possible inclusion in the review. One study is in the final writing-up stage and is awaiting assessment (Rijnders 2007). We have included the remaining three studies, with a total of 612 participants, in the review (Biem 2003; Ryan 1998; Sciscione 2001).

The Sciscione 2001 trial was carried out in the USA and the remaining two studies in Canada (Biem 2003; Ryan 1998). The interventions examined in the three studies all involved initial treatment and monitoring in hospital, with subsequent discharge home for the outpatient groups. The three trials used different cervical ripening/induction agents.

(Three reports from an updated search in February 2012 have been added to Studies awaiting classification.)

(1) Evaluation of vaginal PGE2 in an outpatient versus inpatient setting

In the Ryan 1998 study, the induction agent was vaginal prostaglandin E2; little information was provided on eligibility criteria.

(2) Evaluation of controlled release PGE2 in an outpatient versus inpatient setting

In the Biem 2003 study, women received controlled release prostaglandin E2 10mg. The trial authors set out detailed inclusion criteria, including low obstetric risk and access to reliable transportation. Women randomised to the outpatient group were provided with instructions on when to seek help, had regular telephone contacts by a nurse, and were asked to return to the hospital within 24 hours or less.

(3) Evaluation of the Foley catheter in an outpatient versus inpatient setting

The study by Sciscione 2001 examined the use of a Foley catheter to induce labour. In order to enter the trial, women had to be of low obstetric and medical risk; they were given detailed information on when to seek help; and had 24 hour telephone access to a doctor. Details of the three interventions and full inclusion and exclusion criteria are set out in the Characteristics of included studies table.

Risk of bias in included studies

With interventions where management in different settings are compared, it is not feasible to blind study participants to group allocation, and in the three included studies blinding of the outcome assessors was not attempted. The lack of blinding introduces the potential for bias in these trials and this should be kept in mind when interpreting the results. In the Ryan 1998 study, the results were reported in a conference abstract, and very little information was provided on study methods. In the two other trials, the allocation sequence was computer generated (Biem 2003; Sciscione 2001). In the Biem 2003 study, allocation concealment was by using sequentially numbered, sealed opaque envelopes opened immediately after the insertion of the induction agent, while Sciscione 2001 describes the use of sequentially numbered envelopes. Attrition for outcomes measured in labour was low in all three of these studies, but higher levels of attrition were reported in the Sciscione 2001 study for patient satisfaction outcomes measured in the postnatal period.

Effects of interventions

In view of the fact that the three studies used different methods to induce labour, we have not pooled results in a meta-analysis. Two of the included studies used vaginal prostaglandin E2, but the delivery mechanism was different in each study. A related review (Kelly 2003) provides evidence of different treatment effects depending on the vehicle used to deliver the PGE2.

In the text below, and in the data tables and forest plots, we have described the results for each type of induction method separately; we have calculated no overall effects.

(1) Evaluation of vaginal PGE2 in an inpatient versus outpatient setting (one study, 201 women)

Primary outcomes

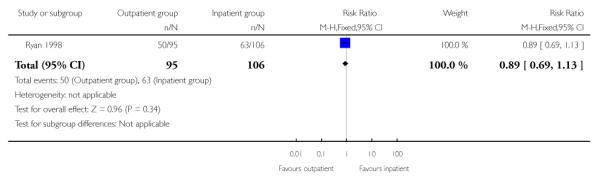

No information was collected in this study on the numbers of women achieving delivery within 24 hours of insertion of the vaginal prostaglandin gel, nor on other primary review outcomes including serious maternal or neonatal morbidity or mortality, maternal satisfaction, or use of emergency services (Ryan 1998). There was no evidence of a difference between groups for the numbers of women requiring a further induction agent (oxytocin) (Analysis 1.6).

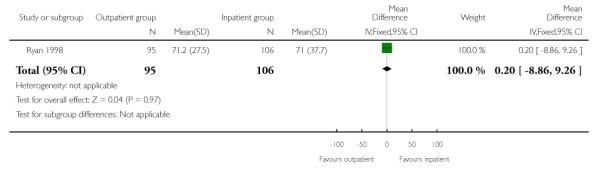

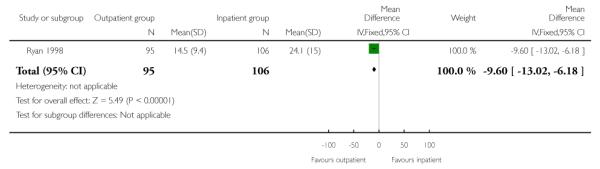

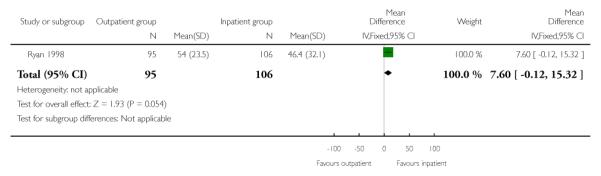

In this study, the total mean length of hospital stay was very similar for those receiving PGE2 and managed as out- and inpatients. While the length of time from admission to delivery was reduced in the outpatient group, this was offset by an increased length of postpartum hospital stay for this group (Analysis 1.1; Analysis 1.2; Analysis 1.3).

Secondary outcomes

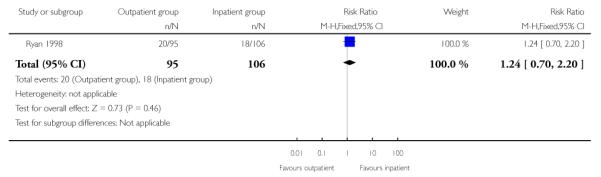

There was no evidence of a difference between groups in terms of the numbers of women undergoing caesarean section (Analysis 1.4).

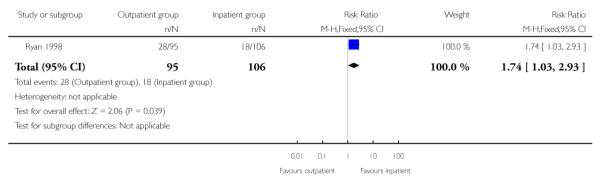

Women receiving vaginal PGE2 were more likely to have an instrumental delivery if they were in the outpatient group compared with those cared for in hospital (29.5% versus 17.0%, risk ratio (RR) 1.74; 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.03 to 2.93) (Analysis 1.5). The rates of instrumental delivery within the outpatient arm of this study are much higher than seen in other studies that have examined the use of vaginal PGE2, and this increase is difficult to explain.

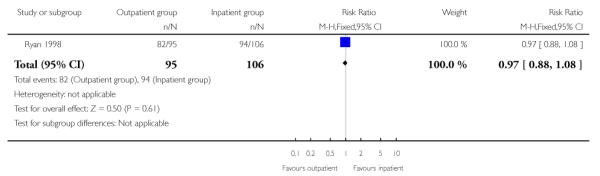

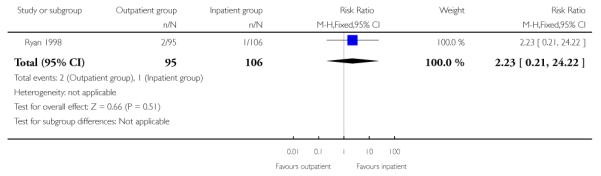

There was no evidence of a difference between groups for the numbers of women receiving epidural analgesia or babies with Apgar scores less than seven at five minutes, or admission to neonatal intensive care.

The authors concluded that “cost-savings for outpatients were $585”, but it was not clear how this figure was calculated.

(2) Evaluation of controlled release PGE2 in outpatient and inpatient settings (one study, 300 women)

Primary outcomes

In this study (Biem 2003), information was collected on most of the primary outcomes of the review.

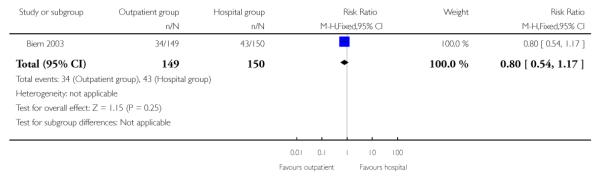

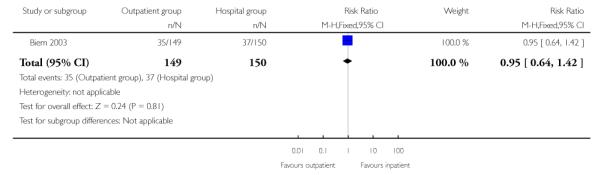

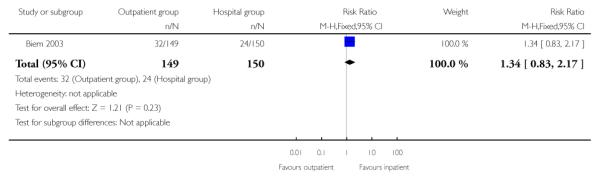

For failure of induction, figures included both those women failing to deliver and those not in spontaneous labour after 24 hours. There was no evidence of a difference between the groups (receiving controlled release prostaglandin) managed at home or as inpatients (22.8% versus 28.7%, RR 0.80; 95% CI 0.54 to 1.17). There was no evidence of differences between groups randomised to outpatient versus inpatient settings for use of additional induction agents, or mode of delivery (Analysis 2.8; Analysis 2.7; Analysis 2.6).

Three mothers were described as experiencing “major delivery complications”. One woman had a caesarean section, and because of bleeding, was transfused four units of blood (outpatient group). One women in the inpatient group had an emergency caesarean section and a uterine rupture necessitating a hysterectomy, a second women in the inpatient group required hysterectomy for postpartum haemorrhage.

This was the only one of the three included studies which provided information on maternal satisfaction for both the outpatient and inpatient groups. Satisfaction and anxiety levels were measured four hourly during the first 12 hours of the induction period (on a scale from zero to nine, women keyed their rating into a telephone keypad to reduce interviewer bias) and mean figures calculated for each woman. Overall satisfaction was also measured on the day after delivery.

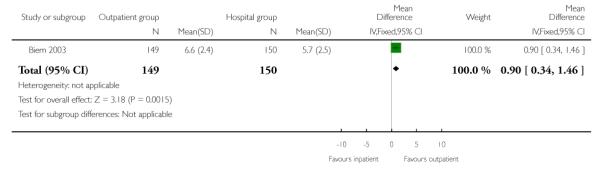

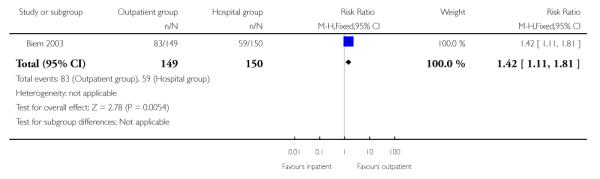

During the induction period, compared with women in the inpatient group, women in the outpatient group rated their satisfaction higher (mean difference 0.90; 95% CI 0.34 to 1.46) and were more likely to report high levels of satisfaction with their care (defined as the numbers of women rating satisfaction higher than seven on a nine-point scale, 55.7% versus 39.3%, RR 1.42; 95% CI 1.11 to 1.81).

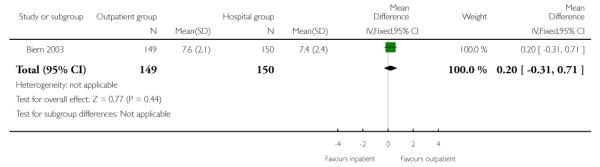

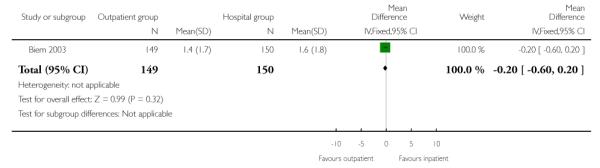

Overall satisfaction with labour and delivery for the two groups (measured postnatally) was similar (Analysis 2.4).

The total length of stay was similar for those managed as outpatients and inpatients for women receiving controlled release prostaglandin (median stay in the outpatient group was reported as 73.6 hours versus 75.6 hours for the inpatient group). (The length of stay was defined as the time from insertion of CR-PGE2 to discharge for the inpatient group, and from admission to discharge for the outpatient group). There was no information on costs or cost savings.

Secondary outcomes

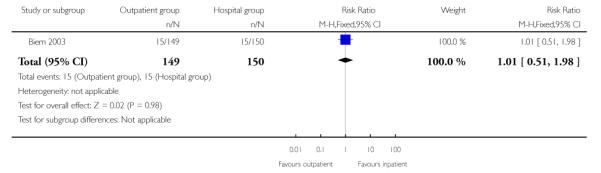

Biem 2003 reported relatively high numbers of women with uterine hyperstimulation (with or without fetal heart rate changes), but there were no differences between groups. This outcome must be interpreted with caution in view of problems with definition and diagnosis (Analysis 2.5).

The median time from induction to delivery was reported as being similar in the two groups: 21.4 hours in the outpatient group and 20.7 hours for the inpatients.

Outcomes for babies were similar in the two groups. There was no evidence of a difference between groups for non-reassuring fetal heart rate patterns, or admission to neonatal intensive care (Analysis 2.10; Analysis 2.11).

Other outcomes

In this study, anxiety was measured during the initial 12 hours of the induction period; there were no significant differences between the outpatient and inpatient groups (Analysis 2.12).

(2) Evaluation of the Foley catheter in outpatient versus inpatient settings (one study, 111 women)

Primary outcomes

In this study (Sciscione 2001), no information was provided on the numbers of women failing to deliver within 24 hours.

Information on patient satisfaction was only provided for the outpatient group and 94.6% (35 of the 37 respondents) reported that they would recommend outpatient induction to someone else. Most of these women (33 of the 37) had been able to remain in their own homes overnight. The response rate for these outcomes measured in the postnatal period was relatively low (37 of the 61 women in the outpatient group responded), so these satisfaction outcomes should be interpreted with caution.

The authors reported that “on average, the outpatient group avoided 9.6 hours of time in the hospital”, but separate figures were not provided on length of hospital stay for those receiving care in the two different settings.

Secondary outcomes

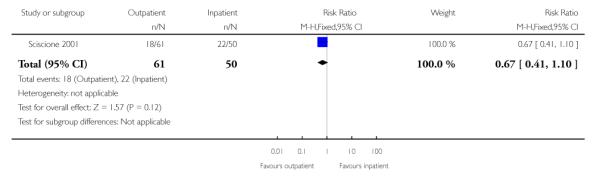

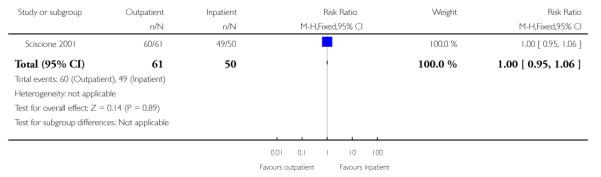

There was no evidence of a difference between groups for the number of women receiving epidural analgesia or the numbers of women delivering by caesarean section (Analysis 3.1; Analysis 3.2).

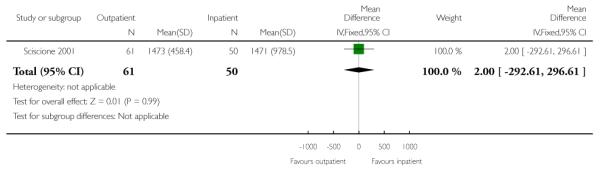

There was no evidence of a difference between groups for the total induction time (Analysis 3.3).

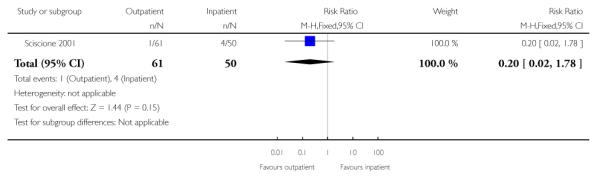

There was little information on outcomes for babies. There was no evidence of any difference between groups in the numbers of babies admitted to special care (Analysis 3.4).

DISCUSSION

Summary of main results

There is a small volume of data currently available to evaluate the efficacy or potential hazards of outpatient induction We found only three trials with 612 women included, and all three used different interventions.

There were very few differences between groups for most of the outcomes measured in this review. On the basis of the available data, it is not possible to determine whether these interventions are effective and safe within an outpatient setting.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

The outcomes chosen for the review reflect measures of both efficacy and harm (both direct, e.g. hyperstimulation and indirect, e.g. use of emergency services).

The studies included in the review did not have the statistical power to detect differences between the randomised groups for most outcomes, and more information is required to assess the safety and effectiveness of methods of induction of labour compared between the inpatient and outpatient setting. In one of the included trials, three women experienced serious labour complications, and the author of this study calls for larger studies in different settings “to compare the frequency of uncommon adverse events in labour and delivery” (Biem 2003).

Interpreting some of the results from the included studies was not simple. Outcome data using time intervals when examining induction of labour are often complicated. There are a variety of start and end points used. The data within these trials are recorded using a variety of methods, which makes comparing findings from studies difficult.

As patient convenience is often cited as a reason for carrying out care in outpatient settings, it is surprising that there is so little information on this. In fact, only one study collected information on maternal satisfaction from women in both arms of the trial. One study looked at maternal anxiety, and this may be useful additional outcome for future updates.

Cost savings are also frequently mentioned as a reason for providing less inpatient care. Again, although all three studies provided some information on length of hospital stay, this did not easily translate into cost data. Without a full breakdown of health service utilisation, it is not possible to impute costs.

The included studies had strict eligibility criteria and it is likely that outpatient cervical ripening and induction is only suitable for selected groups of women. The criteria cited within these studies reflect suitable ‘low-risk’ groups.

We were unable to pool results; it would be helpful to have more trials examining the interventions considered in this review where women are cared for in different settings. Without these direct comparisons between settings, we cannot make the assumption that a method that is known to be safe and effective in one setting would have the same effect in a different one.

Quality of the evidence

The included trials were of varying quality. There was limited information regarding randomisation and concealment in one of the included studies, and ideally, these processes should be explicit to avoid the introduction of bias. When comparing the same intervention within two settings, it is not necessary to blind participants and patients to the actual method if induction of labour, but where possible, researchers assessing outcomes should be blinded to the setting.

AUTHORS’ CONCLUSIONS

Implications for practice

This review highlights the small volume of available evidence relating to cervical ripening and induction of labour in an outpatient setting. Conclusions regarding the efficacy or hazards of cervical ripening and induction on labour in an outpatient setting cannot be drawn from the available evidence.

Implications for research

The recent national UK guideline by The National Institute for Clinical Excellence on intrapartum care (NICE 2008) highlighted the need for more research into the safety and efficacy of outpatient ripening. Further trials are required to assess both efficacy and the potential hazards of initiating labour away from a hospital setting, and researchers are guided to consider the use of outcomes similar to those developed within this review.

[The four citations in the awaiting classification section of the review may alter the conclusions of the review once assessed.]

PLAIN LANGUAGE SUMMARY.

Outpatient versus inpatient induction of labour

Up to a quarter of pregnant women may need their labour started artificially, or induced, with the use of medication or by other means. With most methods of induction it takes some time for labour to actually start. This means that it may be more convenient to women, and cheaper for health service providers, if they are cared for in outpatient settings, such as in their own homes. Women who are at low obstetric or medical risk could be assessed in hospital, given the induction agent and then return home with clear instructions. The use of outpatient induction of labour attempts to balance possible improvements in maternal satisfaction, convenience, reduced length of stay in hospital and lower cost with the safety of both the mother and baby.

Three randomised controlled trials with a combined total of 612 women assessed the effects of induction of labour for women managed as outpatients versus inpatients. The induction agents differed in each trial. The limited information from these trials did not support more successful induction within 24 hours, shorter length of stay in hospital or differences in need for further induction or the mode of giving birth. The information available was limited and it is, therefore, not yet possible to determine whether induction of labour is effective and safe in outpatient settings.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

As part of the pre-publication editorial process, this review has been commented on by three peers (an editor and two referees who are external to the editorial team), a member of the Pregnancy and Childbirth Group’s international panel of consumers and the Group’s Statistical Adviser.

SOURCES OF SUPPORT

Internal sources

The University of Liverpool, UK.

External sources

TD is supported by a grant from the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR), UK.

NIHR NHS Cochrane Collaboration Programme Grant Scheme award for NHS prioritised, centrally-managed, pregnancy and childbirth systematic reviews: CPGS02

CHARACTERISTICS OF STUDIES

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

| Methods | RCT. | |

| Participants | 300 women randomised (1 woman withdrew). Inclusion criteria: singleton, term pregnancy, cephalic presentation, intact membranes, Bishop’s score 6 or less, parity 5 or less, unscarred uterus, normal nonstress test, reliable transportation from home Exclusion criteria: congenital anomaly, dead fetus, IUGR, hypertension, abnormal placenta, poly- or oligohydramnios |

|

| Interventions | Both groups received vaginal controlled release prostaglandin E2 10mg. Both groups were monitored in the antenatal ward for 1 hour Outpatient group: after initial monitoring women were discharged home to return when in labour or were reviewed after 12 hours (nonstress test). If they were not in labour 24 hours later they returned to hospital for induction of labour as an inpatient. Women were in telephone contact with a nurse every 4 hours and were given detailed instructions on when to seek help. They were asked to remain within easy travelling distance of the hospital Inpatient group: women remained on the antenatal ward throughout and managed in a similar way to the outpatient group |

|

| Outcomes | Satisfaction with care, length of hospital stay, length of labour, mode of delivery, labour interventions, maternal, fetal and neonatal complications | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors’ judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Computer-generated sequence. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | “Sequential sealed opaque envelopes” opened immediately after the insertion of the PGE2 |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) Women |

High risk | Not feasible for this intervention. |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) Clinical staff |

High risk | |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) Outcome assessors |

High risk | |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes |

Low risk | Only 1 woman withdrew from the study after randomisation. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | None apparent. |

| Other bias | Low risk | None apparent. No baseline imbalance apparent. |

| Methods | RCT. | |

| Participants | 201 women. Inclusion and exclusion criteria were not clear. Women at “term… who met the eligibility criteria to receive PGE2 as an outpatient” |

|

| Interventions | Unclear. Information not provided. Inpatient and outpatient management after insertion of PGE2 gel (dose not stated) were compared | |

| Outcomes | Length of hospital stay, mode of delivery, Apgar score and neonatal admission to special care | |

| Notes | Abstract only available, we have attempted to contact the author for more information but to date (November 2008) we have had no response | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors’ judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Described as “randomised”. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | No information provided. |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) Women |

High risk | Not feasible. |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) Clinical staff |

High risk | |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) Outcome assessors |

High risk | |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes |

Unclear risk | No loss to follow up apparent but little information provided |

| Methods | RCT. | |

| Participants | 111 women. Inclusion criteria: singleton, term pregnancy, cephalic position, intact membranes with a Bishop’s score < 6, with reactive nonstress test, “…attending physician had requested preinduction cervical ripening using the Foley catheter” Exclusion criteria: fetal anomaly or dead fetus, hypertension, vaginal bleeding, ruptured membranes, placenta praevia, IUGR, active herpes infection, without access to phone, without reliable transportation or living more than 30 minutes’ distance from the hospital |

|

| Interventions | Both groups had a number 16 Foley catheter inserted into the endocervical canal to or past the internal os; the balloon was filled with 30 ml of sterile water, the end of the catheter was taped to the thigh. After placement of the catheter if there was a reactive nonstress test and no signs of uterine hyperstimulation and the amniotic fluid index was > 5th percentile women were randomised Outpatient group: women received detailed oral and written guidelines on when to seek advice and then were discharged home. 24 hour phone access to a doctor was provided. They were asked to return for review the next morning for induction of labour with oxytocin Inpatient group: women were admitted to the labour ward. They were allowed to ambulate. The catheter was checked every 2-4 hrs and the fetal heart rate was assessed hourly |

|

| Outcomes | Primary outcome: Bishop score. | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors’ judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Computer-generated random number table. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Sequentially numbered envelopes. |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) Women |

High risk | Blinding not attempted. |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) Clinical staff |

High risk | |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) Outcome assessors |

High risk | |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes |

Low risk | Complete data for main outcomes. Only the outpatient group was followed up in the postnatal period and there was high attrition (40%) for this longer term follow up |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Some of the results were difficult to interpret. |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | Not clear how many of the women approached were eligible for this trial. Not clear how women were managed as regards oxytocin and this may have had an impact on results. Not clear how many women in the outpatient group were surveyed in the postnatal period; figures differ between the main study paper and an abstract reporting survey results |

RCT: randomised controlled trial

Characteristics of studies awaiting assessment [ordered by study ID]

| Methods | |

| Participants | |

| Interventions | |

| Outcomes | |

| Notes |

| Methods | |

| Participants | |

| Interventions | |

| Outcomes | |

| Notes |

| Methods | RCT. |

| Participants | Target number of participants: 500. |

| Interventions | Study examining the costs and effectiveness of home versus hospital amniotomy for low-risk women |

| Outcomes | |

| Notes | We have contacted the study authors. The study is in the final writing up stages (autumn 2008) and the authors will be contacted again before the review is updated |

| Methods | |

| Participants | |

| Interventions | |

| Outcomes | |

| Notes |

RCT: randomised controlled trial

Characteristics of ongoing studies [ordered by study ID]

| Trial name or title | RCT of outpatient cervical priming for induction of labour (from the Australian and New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry) |

| Methods | Multicentre randomised trial. |

| Participants | Women having priming for induction of labour where induction is clinically indicated and there is no evidence of maternal or fetal compromise |

| Interventions | Study comparing outpatient versus inpatient cervical priming with intravaginal prostaglandins for induction of labour |

| Outcomes | Syntocinon usage; obstetric interventions; pregnancy complications; economic evaluation; maternal satisfaction |

| Starting date | 1.07.08 |

| Contact information | Contact Dr Chris Wilkinson chris.wilkinson@cywhs.sa.gov.au |

| Notes | The study aims to find out whether or not it is good practice to permit pregnant women to go home to rest after they have had induction of labour started. It aims to identify the potential advantages and disadvantages of this approach to inform choice |

DATA AND ANALYSES

Comparison 1.

Outpatient versus inpatient induction with vaginal PGE2

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Total length of hospital stay | 1 | 201 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.20 [−8.86, 9.26] |

| 2 Length of stay: admission to delivery | 1 | 201 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | −9.60 [−13.02, −6.18] |

| 3 Postnatal hospital stay | 1 | 201 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 7.60 [−0.12, 15.32] |

| 4 Caesarean section rate | 1 | 201 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.24 [0.70, 2.20] |

| 5 Instrumental vaginal delivery | 1 | 201 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.74 [1.03, 2.93] |

| 6 Additional induction agent required (oxytocin) | 1 | 201 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.89 [0.69, 1.13] |

| 7 Women receiving epidural analgesia | 1 | 201 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.97 [0.88, 1.08] |

| 8 Apgar score less than 7 at 5 minutes | 1 | 201 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.23 [0.21, 24.22] |

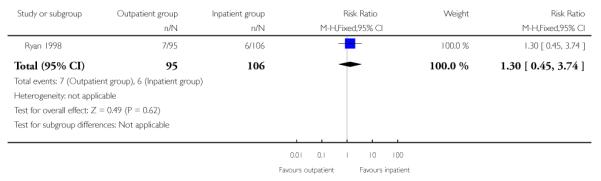

| 9 Neonatal intensive care unit admission | 1 | 201 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.30 [0.45, 3.74] |

Comparison 2.

Outpatient versus inpatient induction with controlled release PGE

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Vaginal delivery or labour not achieved within 24 hours | 1 | 299 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.80 [0.54, 1.17] |

| 2 Mean satisfaction score measured during induction | 1 | 299 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.90 [0.34, 1.46] |

| 3 High level of maternal satisfaction measured during induction period | 1 | 299 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.42 [1.11, 1.81] |

| 4 Overall satisfaction score with labour and delivery measured in the postnatal period | 1 | 299 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.20 [−0.31, 0.71] |

| 5 Uterine hyperstimulation (with or without fetal heart rate changes) | 1 | 299 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.01 [0.51, 1.98] |

| 6 Caesarean section rate | 1 | 299 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.95 [0.64, 1.42] |

| 7 Instrumental vaginal delivery | 1 | 299 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.34 [0.83, 2.17] |

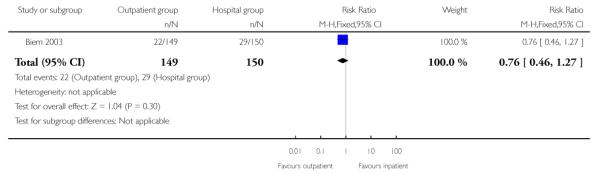

| 8 Oxytocin required | 1 | 299 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.76 [0.46, 1.27] |

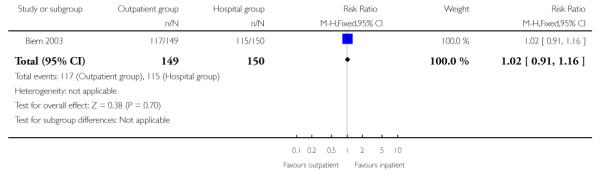

| 9 Number receiving epidural | 1 | 299 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.02 [0.91, 1.16] |

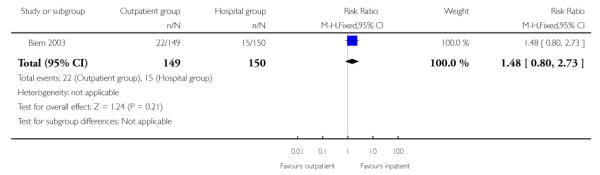

| 10 Nonreassuring fetal heart rate | 1 | 299 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.48 [0.80, 2.73] |

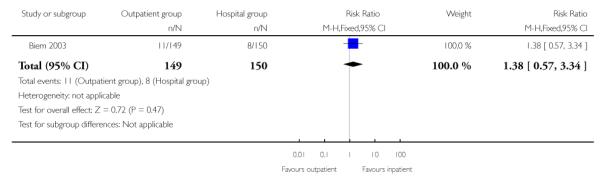

| 11 Neonatal intensive care admission | 1 | 299 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.38 [0.57, 3.34] |

| 12 Anxiety score measured during induction period | 1 | 299 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | −0.20 [−0.60, 0.20] |

Comparison 3.

Outpatient versus inpatient induction with Foley catheter

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Caesarean section rate | 1 | 111 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.67 [0.41, 1.10] |

| 2 Women receiving epidural analgesia | 1 | 111 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.00 [0.95, 1.06] |

| 3 Total induction time (insertion of catheter to delivery) | 1 | 111 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.0 [−292.61, 296. 61] |

| 4 Neonatal intensive care unit admission | 1 | 111 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.20 [0.02, 1.78] |

Analysis 1.1. Comparison 1 Outpatient versus inpatient induction with vaginal PGE2, Outcome 1 Total length of hospital stay

Review: Outpatient versus inpatient induction of labour for improving birth outcomes

Comparison: 1 Outpatient versus inpatient induction with vaginal PGE2

Outcome: 1 Total length of hospital stay

|

Analysis 1.2. Comparison 1 Outpatient versus inpatient induction with vaginal PGE2, Outcome 2 Length of stay: admission to delivery

Review: Outpatient versus inpatient induction of labour for improving birth outcomes

Comparison: 1 Outpatient versus inpatient induction with vaginal PGE2

Outcome: 2 Length of stay: admission to delivery

|

Analysis 1.3. Comparison 1 Outpatient versus inpatient induction with vaginal PGE2, Outcome 3 Postnatal hospital stay

Review: Outpatient versus inpatient induction of labour for improving birth outcomes

Comparison: 1 Outpatient versus inpatient induction with vaginal PGE2

Outcome: 3 Postnatal hospital stay

|

Analysis 1.4. Comparison 1 Outpatient versus inpatient induction with vaginal PGE2, Outcome 4 Caesarean section rate

Review: Outpatient versus inpatient induction of labour for improving birth outcomes

Comparison: 1 Outpatient versus inpatient induction with vaginal PGE2

Outcome: 4 Caesarean section rate

|

Analysis 1.5. Comparison 1 Outpatient versus inpatient induction with vaginal PGE2, Outcome 5 Instrumental vaginal delivery

Review: Outpatient versus inpatient induction of labour for improving birth outcomes

Comparison: 1 Outpatient versus inpatient induction with vaginal PGE2

Outcome: 5 Instrumental vaginal delivery

|

Analysis 1.6. Comparison 1 Outpatient versus inpatient induction with vaginal PGE2, Outcome 6 Additional induction agent required (oxytocin)

Review: Outpatient versus inpatient induction of labour for improving birth outcomes

Comparison: 1 Outpatient versus inpatient induction with vaginal PGE2

Outcome: 6 Additional induction agent required (oxytocin)

|

Analysis 1.7. Comparison 1 Outpatient versus inpatient induction with vaginal PGE2, Outcome 7 Women receiving epidural analgesia

Review: Outpatient versus inpatient induction of labour for improving birth outcomes

Comparison: 1 Outpatient versus inpatient induction with vaginal PGE2

Outcome: 7 Women receiving epidural analgesia

|

Analysis 1.8. Comparison 1 Outpatient versus inpatient induction with vaginal PGE2, Outcome 8 Apgar score less than 7 at 5 minutes

Review: Outpatient versus inpatient induction of labour for improving birth outcomes

Comparison: 1 Outpatient versus inpatient induction with vaginal PGE2

Outcome: 8 Apgar score less than 7 at 5 minutes

|

Analysis 1.9. Comparison 1 Outpatient versus inpatient induction with vaginal PGE2, Outcome 9 Neonatal intensive care unit admission

Review: Outpatient versus inpatient induction of labour for improving birth outcomes

Comparison: 1 Outpatient versus inpatient induction with vaginal PGE2

Outcome: 9 Neonatal intensive care unit admission

|

Analysis 2.1. Comparison 2 Outpatient versus inpatient induction with controlled release PGE, Outcome 1 Vaginal delivery or labour not achieved within 24 hours

Review: Outpatient versus inpatient induction of labour for improving birth outcomes

Comparison: 2 Outpatient versus inpatient induction with controlled release PGE

Outcome: 1 Vaginal delivery or labour not achieved within 24 hours

|

Analysis 2.2. Comparison 2 Outpatient versus inpatient induction with controlled release PGE, Outcome 2 Mean satisfaction score measured during induction

Review: Outpatient versus inpatient induction of labour for improving birth outcomes

Comparison: 2 Outpatient versus inpatient induction with controlled release PGE

Outcome: 2 Mean satisfaction score measured during induction

|

Analysis 2.3. Comparison 2 Outpatient versus inpatient induction with controlled release PGE, Outcome 3 High level of maternal satisfaction measured during induction period

Review: Outpatient versus inpatient induction of labour for improving birth outcomes

Comparison: 2 Outpatient versus inpatient induction with controlled release PGE

Outcome: 3 High level of maternal satisfaction measured during induction period

|

Analysis 2.4. Comparison 2 Outpatient versus inpatient induction with controlled release PGE, Outcome 4 Overall satisfaction score with labour and delivery measured in the postnatal period

Review: Outpatient versus inpatient induction of labour for improving birth outcomes

Comparison: 2 Outpatient versus inpatient induction with controlled release PGE

Outcome: 4 Overall satisfaction score with labour and delivery measured in the postnatal period

|

Analysis 2.5. Comparison 2 Outpatient versus inpatient induction with controlled release PGE, Outcome 5 Uterine hyperstimulation (with or without fetal heart rate changes)

Review: Outpatient versus inpatient induction of labour for improving birth outcomes

Comparison: 2 Outpatient versus inpatient induction with controlled release PGE

Outcome: 5 Uterine hyperstimulation (with or without fetal heart rate changes)

|

Analysis 2.6. Comparison 2 Outpatient versus inpatient induction with controlled release PGE, Outcome 6 Caesarean section rate

Review: Outpatient versus inpatient induction of labour for improving birth outcomes

Comparison: 2 Outpatient versus inpatient induction with controlled release PGE

Outcome: 6 Caesarean section rate

|

Analysis 2.7. Comparison 2 Outpatient versus inpatient induction with controlled release PGE, Outcome 7 Instrumental vaginal delivery

Review: Outpatient versus inpatient induction of labour for improving birth outcomes

Comparison: 2 Outpatient versus inpatient induction with controlled release PGE

Outcome: 7 Instrumental vaginal delivery

|

Analysis 2.8. Comparison 2 Outpatient versus inpatient induction with controlled release PGE, Outcome 8 Oxytocin required

Review: Outpatient versus inpatient induction of labour for improving birth outcomes

Comparison: 2 Outpatient versus inpatient induction with controlled release PGE

Outcome: 8 Oxytocin required

|

Analysis 2.9. Comparison 2 Outpatient versus inpatient induction with controlled release PGE, Outcome 9 Number receiving epidural

Review: Outpatient versus inpatient induction of labour for improving birth outcomes

Comparison: 2 Outpatient versus inpatient induction with controlled release PGE

Outcome: 9 Number receiving epidural

|

Analysis 2.10. Comparison 2 Outpatient versus inpatient induction with controlled release PGE, Outcome 10 Nonreassuring fetal heart rate

Review: Outpatient versus inpatient induction of labour for improving birth outcomes

Comparison: 2 Outpatient versus inpatient induction with controlled release PGE

Outcome: 10 Nonreassuring fetal heart rate

|

Analysis 2.11. Comparison 2 Outpatient versus inpatient induction with controlled release PGE, Outcome 11 Neonatal intensive care admission

Review: Outpatient versus inpatient induction of labour for improving birth outcomes

Comparison: 2 Outpatient versus inpatient induction with controlled release PGE

Outcome: 11 Neonatal intensive care admission

|

Analysis 2.12. Comparison 2 Outpatient versus inpatient induction with controlled release PGE, Outcome 12 Anxiety score measured during induction period

Review: Outpatient versus inpatient induction of labour for improving birth outcomes

Comparison: 2 Outpatient versus inpatient induction with controlled release PGE

Outcome: 12 Anxiety score measured during induction period

|

Analysis 3.1. Comparison 3 Outpatient versus inpatient induction with Foley catheter, Outcome 1 Caesarean section rate

Review: Outpatient versus inpatient induction of labour for improving birth outcomes

Comparison: 3 Outpatient versus inpatient induction with Foley catheter

Outcome: 1 Caesarean section rate

|

Analysis 3.2. Comparison 3 Outpatient versus inpatient induction with Foley catheter, Outcome 2 Women receiving epidural analgesia

Review: Outpatient versus inpatient induction of labour for improving birth outcomes

Comparison: 3 Outpatient versus inpatient induction with Foley catheter

Outcome: 2 Women receiving epidural analgesia

|

Analysis 3.3. Comparison 3 Outpatient versus inpatient induction with Foley catheter, Outcome 3 Total induction time (insertion of catheter to delivery)

Review: Outpatient versus inpatient induction of labour for improving birth outcomes

Comparison: 3 Outpatient versus inpatient induction with Foley catheter

Outcome: 3 Total induction time (insertion of catheter to delivery)

|

Analysis 3.4. Comparison 3 Outpatient versus inpatient induction with Foley catheter, Outcome 4 Neonatal intensive care unit admission

Review: Outpatient versus inpatient induction of labour for improving birth outcomes

Comparison: 3 Outpatient versus inpatient induction with Foley catheter

Outcome: 4 Neonatal intensive care unit admission

|

Appendix 1. Methods for updating the review

Planned analyses in updates of the review

In future updates of the review, if more than one study examines the same intervention, we will pool the results from studies and carry out meta-analyses using the methods set out in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2008).

For dichotomous data, we will present results as summary risk ratio with 95% confidence intervals.

For continuous data, we will use the mean difference if outcomes were measured in the same way between trials. We will use the standardised mean difference to combine trials that measure the same outcome, but use different methods. Again we will report 95% confidence intervals.

We will assess heterogeneity by visual inspection of the outcomes, and by applying tests of heterogeneity between trials using the I2 statistic. If we identify heterogeneity among the trials, we will explore it by prespecified subgroup analysis and perform sensitivity analyses.

As more data become available, we plan to conduct subgroup analyses using the methods described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2008). Data permitting, we would perform subgroup analyses by: nulliparous women; induction indication, i.e. postdates (41 weeks or greater).

Sensitivity analyses: in updates of the review, if results from more than one trial are pooled we will carry out sensitivity analyses to explore the effect of trial quality for important outcomes in the review. Where there is risk of bias associated with a particular aspect of study quality (e.g. inadequate allocation concealment or high levels of missing data), we will explore this by sensitivity analyses. Analysis of cluster-randomised trials: if we identify cluster randomised trials that are eligible for inclusion, we will include such trials in analyses along with individually randomised trials. Their sample sizes will be adjusted using the methods described in Gates 2005 using an estimate of the intracluster correlation co-efficient (ICC) derived from the trial (if possible), or from another source. If ICCs from other sources are used, we will report this and conduct sensitivity analyses to investigate the effect of variation in the ICC. If we identify both cluster randomised trials and individually randomised trials, we plan to synthesise the relevant information. We will consider it reasonable to combine the results from both if there is little heterogeneity between the study designs and the interaction between the effect of intervention and the choice of randomisation unit is considered to be unlikely. We will also acknowledge heterogeneity in the randomisation unit and perform a separate meta-analysis. Therefore, we will perform the meta-analysis in two parts as well.

HISTORY

Protocol first published: Issue 4, 2008

Review first published: Issue 2, 2009

DIFFERENCES BETWEEN PROTOCOL AND REVIEW

Planned methods for updating the review have been removed from the main text and placed in Appendix 1.

WHAT’S NEW

Last assessed as up-to-date: 28 December 2008.

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 24 February 2012 | Amended | Search updated. Three reports added to Studies awaiting classification (Henry 2011; Henry 2011a; Wilkinson 2012) |

Footnotes

DECLARATIONS OF INTEREST None known.

References to studies included in this review

* Indicates the major publication for the study

- Biem 2003 {published data only} .Biem SRD, Turnell RW, Olatunbosun O, Tauh M, Biem HJ. A randomized controlled trial of outpatient versus inpatient labour induction with vaginal controlled-release prostaglandin-E2: effectiveness and satisfaction. Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology Canada: JOGC. 2003;25(1):23–31. doi: 10.1016/s1701-2163(16)31079-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan 1998 {published data only} .Ryan G, Oskamp M, Seaward PGR, Barrett J, Barrett H, O’Brien K, et al. Randomized controlled trial of inpatient vs. outpatient administration of prostaglandin E2, gel for induction of labour at term [SPO Abstract 303] American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1998;178(1 Pt 2):S92. [Google Scholar]

- Sciscione 2001 {published data only} .Pollock M, Maas B, Muench M, Sciscione A. Patient acceptance of outpatient pre-induction cervical ripening with the foley bulb. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2000;182(1 Pt 2):S136. [Google Scholar]; *; Sciscione AC, Muench M, Pollock M, Jenkins TM, Tildon-Burton J, Colmorgen GHC. Transcervical foley catheter for preinduction cervical ripening in an outpatient versus inpatient setting. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2001;98:751–6. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(01)01579-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References to studies awaiting assessment

- Henry 2011 {published data only} .Henry A, Madan A, Reid R, Tracy S, Sharpe V, Austin K, et al. Outpatient Foley catheter versus inpatient Prostin gel for cervical ripening: the FOG (Foley or Gel) trial. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2011;51:473–4. [Google Scholar]

- Henry 2011a {published data only} .Henry A, Reid R, Madan A, Tracy S, Sharpe V, Welsh A, et al. Satisfaction survey: outpatient Foley catheter versus inpatient Prostin gel for cervical ripening. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2011;51:474. [Google Scholar]

- Rijnders 2007 {published data only} .Rijnders MEB. [accessed 15.02.2007];Costs and effects of amniotomy at home for induction of post term pregnancy (ongoing trial) Current Controlled Trials. http://controlled-trials.com.

- Wilkinson 2012 {published data only} .Wilkinson C, Bryce R, Adelson P, Coffey J, Coomblas J, Ryan P, et al. Two center RCT of outpatient versus inpatient cervical ripening for induction of labour with PGE2. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2012;206(Suppl 1):S137. [Google Scholar]

References to ongoing studies

- Adelaide 2009 {published data only} .Turnbull D. [accessed 8 January 2009];A multicentre randomised controlled trial comparing outpatient and inpatient cervical priming with intravaginal prostaglandins for induction of labour. Australian Clinical Trials Register. http://www.actr.org/actr.

Additional references

- Calder 1998 .Calder AA. Nitric oxide--another factor in cervical ripening. Human Reproduction. 1998;13(2):250–1. doi: 10.1093/humrep/13.2.250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis 1987 .Curtis P, Evans S, Resnick J. Uterine hyperstimulation. The need for standard terminology. Journal of Reproductive Medicine. 1987;32:91–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gates 2005 .Gates S, The Editorial Team. Pregnancy and Childbirth Group . About The Cochrane Collaboration (Collaborative Review Groups (CRGs)) Issue 2 2005. Methodological Guidelines. [Google Scholar]

- Higgins 2008 .Higgins JPT, Green S, editors. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Version 5.0.0. The Cochrane Collaboration; [updated February 2008]. 2008. Available from www.cochrane-handbook.org. [Google Scholar]

- Hofmeyr 2000 .Hofmeyr GJ, Alfirevic Z, Kelly T, Kavanagh J, Thomas J, Brocklehurst P, et al. Methods for cervical ripening and labour induction in later pregnancy:generic protocol. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2000;(Issue 2) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000941. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD002074] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly 2001 .Kelly A, Alfirevic Z, Hofmeyr GJ, Kavanagh J, Neilson JP, Thomas J. Induction of labour in specific clinical situations: generic protocol. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2001;(Issue 4) [Art. No.: CD003398. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD003398] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly 2003 .Kelly AJ, Kavanagh J, Thomas J. Vaginal prostaglandin (PGE2 and PGF2a) for induction of labour at term. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2003;(Issue 4) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003101. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD003101] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly 2009 .Kelly AJ, Alfirevic Z, Norman JE, Dowswell T. Different methods for the induction of labour in outpatient settings. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2009;(Issue 2) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007701.pub2. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD007701] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NHS 2007 .Richardson A, Mmata C. NHS Maternity Statistics, England: 2005-06. National Statistics, The Information Centre; London: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- NICE 2008 .National Collaborating Centre for Women’s and Children’s Health . Induction of labour: Clinical Guideline. RCOG Press; London: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- RevMan 2008 .The Cochrane Collaboration . Review Manager (RevMan) 5.0 The Nordic Cochrane Centre: The Cochrane Collaboration; Copenhagen: 2008. [Google Scholar]