Abstract

Atrial fibrillation (AF) and heart failure (HF) are common cardiovascular diseases and the co-occurrence of AF and HF is associated with reduced survival. Data are needed on potentially changing trends in the characteristics, treatment, and prognosis of patients with acute decompensated HF (ADHF) and AF. The study population consisted of 9,748 patients hospitalized with ADHF at 11 hospitals in the Worcester, MA, metropolitan area in 4 study periods between 1995 and 2004. 3,868 (39.7%) of patients admitted with ADHF had a history of AF and 449 (4.6%) developed new-onset AF during hospitalization. Rates of new-onset AF remained stable (4.9% in 1995; 5.0% in 2004), whereas the proportion of patients with pre-existing AF (34.5% in 1995; 41.6% in 2004) increased over time. New-onset and pre-existing AF were associated with older age, but pre-existing AF was more closely linked to greater comorbid disease burden. Treatment with HF therapies did not differ greatly by AF status. Despite this, new-onset AF was associated with longer length of stay (7.5 vs. 6.1 days) and higher in-hospital death rates (11.4% vs. 6.6%), whereas pre-existing AF was associated with lower rates of post-discharge survival compared to patients with no AF (all p’s<0.05). Mortality rates improved significantly over time in patients with AF. In conclusion, AF was common among patients with ADHF and the proportion of ADHF patients with co-occurring AF increased during the years under study. Despite improving trends in survival, patients with ADHF and AF are at increased risk for in-hospital and post-discharge mortality.

Keywords: heart failure, atrial fibrillation, community trends

Introduction

Heart failure (HF) and atrial fibrillation (AF) represent two global cardiovascular disease epidemics.1,2 The prevalence of AF is high and ever-increasing concomitant with the aging of the U.S. population,2,3 likely because this arrhythmia disproportionately affects older individuals and those with HF. The impact of AF on the quality of life and longevity of affected patients is profound as AF is associated with higher hospitalization rates, lower quality of life, a markedly higher risk for ischemic stroke,4 and reduced survival.5 Approximately 1 in 3 patients with HF also have AF and upwards of 40% of patients diagnosed with HF develop AF within 10 years of their diagnosis.6–8 However, the epidemiology, treatment, and prognosis of AF and HF have changed in recent years and several reports suggest that AF is no longer associated with increased mortality in well-treated patients with HF.9–15 There may also be differences in the prognosis of AF developing prior to, as compared with after, HF onset.16 Despite conflicting data on the prognostic import of AF17,18 and its changing treatment,19 limited relatively recent information exists on the incidence, treatment, in-hospital and long-term outcomes of patients hospitalized with HF further categorized according to the presence and type of AF.

Methods

The Worcester Heart Failure Study is a community-based investigation including adult residents from the Worcester, MA, metropolitan area (2000 census population estimates = 478,000) who were hospitalized for ADHF at any of 11 greater Worcester medical centers during 4 study years (1995, 2000, 2002, and 2004). Primary and/or secondary International Classification of Disease discharge diagnoses consistent with possible HF were reviewed in a standardized fashion as has been previously outlined in detail. 11 Patients with a discharge diagnosis of HF, as well as patients with discharge diagnoses of rheumatic HF, hypertensive heart and renal disease, cardiomyopathy, pulmonary heart disease and congestion, acute lung edema, edema, dyspnea, acute cor pulmonale, pulmonary heart disease and congestion, dyspnea, and respiratory abnormalities had their charts reviewed by trained study physicians and nurses to identify hospitalized patients with ADHF. The diagnosis of HF was confirmed using the Framingham criteria and required that patients have at least 2 major, or 1 major and 2 minor, criteria for HF present.20 Incident HF was considered to be present if a patient did not have a prior hospitalization for HF noted, a prior physician diagnosis of HF, or treatment for HF based on hospital record review. Patients with HF secondary to another acute illness, after surgery, or after an interventional procedure were excluded.

Trained study staff abstracted demographic, clinical, treatment, and laboratory information from patients’ medical records. Information was collected about patients’ age, sex, comorbidities, length of hospital stay, and hospital discharge status. We reviewed physicians’ progress notes and medication logs for prescribing of cardiac medications, especially those thought to be of benefit in improving the prognosis (e.g., beta-blockers, angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors) or symptoms (e.g., diuretics, digoxin) of patients with ADHF. Short and long-term survival status was determined through a comprehensive review of all regional hospital records for other medical care contacts and by reviewing the Social Security Death Index and death certificates at the Massachusetts State Health Department.

Patients with pre-existing AF were identified on the basis of documentation of AF at any previous time in their medical history. Presence of AF was determined based on data from the medical record and review of all electrocardiograms obtained during hospitalization for ADHF. The criteria used to define new-onset AF in this study were electrocardiographic changes consistent with AF on admission or at any point during their hospitalization among persons without a prior history of AF.

We examined differences in the characteristics and treatment of patients with pre-existing, new-onset, and no AF using t tests and chi square tests for continuous and discrete variables, respectively. Logistic regression analysis was used to examine changes over time in the rates of new-onset and pre-existing AF, adjusting for factors associated with risk for AF (age, sex, race, length of stay, history of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, stroke, anemia, diabetes, coronary heart disease, coronary artery bypass graft, as well as admission systolic and diastolic blood pressures, heart rate, creatinine, and serum glucose). In-hospital and post-discharge case-fatality rates (CFRs) were calculated in a standard manner. Multivariate logistic regression was used to examine the association between type of AF and in-hospital, 1-year, and 2-year post-admission mortality while controlling for previously described factors of prognostic importance. We did not attempt to control for the receipt of medications or interventional therapies due to the substantial risk for confounding by treatment indication as well as lack of information on the timing of therapy administration relative to AF onset. Analyses were conducted using SAS (Version 9.2, SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC).

Results

The mean age of study participants was 76.2 years, 56.1% were women, and 93.3% were white. Of the 9,748 patients admitted with ADHF between 1995 and 2004, 3,868 patients (39.7%) had a history of AF and 449 (4.6%) developed new-onset AF during hospitalization (Table 1). Higher rates of new-onset AF were observed in patients without a history of HF (7.0% vs 3.6%).

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Patients with Acute Heart Failure according to the presence and type of Atrial Fibrillation (AF)

| Variable* | New-Onset AF (n=449) | P Value (New vs. No) | Pre-existing AF (n=3868) | P Value (Pre vs. No) | No AF (n=5431) | P Value (New vs. Pre) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 78.5 ± 11.0 | <0.001 | 79.1 ± 9.95 | <0.001 | 73.9 ± 13.1 | 0.23 |

| Male | 206 (45.9%) | 0.20 | 1757 (45.4%) | <0.05 | 2321 (42.7%) | 0.85 |

| White race | 433 (96.4%) | <0.001 | 3709 (95.9%) | <0.001 | 4949 (91.1%) | 0.57 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 28.2 +/− 8.4 | 0.18 | 27.1 +/− 9.3 | <0.001 | 28.9 +/− 9.1 | <0.05 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 140.6 +/− 31.4 | <0.001 | 138.7 +/− 30.3 | <0.001 | 146.1 +/− 34.3 | 0.21 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 77.2 +/− 20.7 | 0.16 | 72.8 +/− 18.6 | <0.001 | 75.8 +/− 20.4 | <0.001 |

| Pulse (bpm) | 96.5 +/− 27.2 | <0.001 | 88.9 +/− 24.1 | 0.53 | 89.2 +/− 21.3 | <0.001 |

| Length of stay (days) | 7.54+/−7.92 | <0.05 | 6.14+/−8.69 | 0.56 | 6.07+/−7.01 | <0.05 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 150 (33.4%) | 0.46 | 1441 (37.3%) | <0.05 | 1909 (35.2%) | 0.11 |

| Anemia | 86 (19.2%) | 0.07 | 1077 (27.8%) | <0.001 | 1236 (22.8%) | <0.001 |

| Coronary heart disease | 200 (44.5%) | <0.001 | 2329 (60.2%) | <0.001 | 2927 (53.7%) | <0.001 |

| Heart failure | 252 (56.1%) | <0.001 | 3105 (80.3%) | <0.001 | 3557 (65.5%) | <0.001 |

| Angina | 63 (14.0%) | <0.05 | 642 (16.6%) | 0.21 | 956 (17.6%) | 0.16 |

| Coronary artery bypass graft | 70 (15.6%) | 0.06 | 956 (24.7%) | <0.001 | 1038 (19.1%) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 135 (30.1%) | <0.001 | 1371 (35.4%) | <0.001 | 2301 (42.4%) | <0.05 |

| Hypertension | 304 (67.7%) | 0.72 | 2667 (69.0%) | 0.67 | 3722 (68.5%) | 0.59 |

| Stroke | 47 (10.5%) | 0.17 | 564 (14.6%) | <0.05 | 687 (12.7%) | <0.05 |

| Renal disease | 93 (20.7%) | <0.05 | 1036 (26.8%) | 0.29 | 1401 (25.8%) | <0.01 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 73 (16.3%) | 0.08 | 780 (20.2%) | 0.49 | 1064 (19.6%) | <0.05 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.6 +/− 1.4 | 0.11 | 1.6 +/− 1.0 | <0.001 | 1.71 +/− 1.9 | 0.93 |

| eGFR (ml/min/1.73 m2) | 54.1 +/− 59.2 | 0.89 | 51.0 +/− 24.9 | <0.001 | 53.7 +/− 31.7 | 0.27 |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL) | 150.4 +/− 46.1 | <0.01 | 156.3 +/− 50.7 | <0.001 | 168.1 +/− 51.1 | 0.31 |

| Glucose (mg/dL) | 154.6 +/− 69.8 | <0.01 | 153.2 +/− 71.6 | <0.001 | 166.3 +/− 82.3 | 0.70 |

| B-type natriuretic peptide (ng/L) | 906.3 +/− 906.6 | 0.07 | 959.6 +/− 1079.1 | <0.05 | 1120.8 +/− 1272.8 | 0.69 |

| Baseline ejection fraction (%)** | 45.7 +/− 16.5 | 0.84 | 45.5 +/− 25.2 | 0.90 | 45.5 +/− 20.0 | 0.91 |

| Left bundle branch block | 41 (9.1%) | 0.58 | 410 (10.6%) | 0.31 | 538 (9.9%) | 0.34 |

Mean (± SD), laboratory values obtained from admission. The presence of non-cardiovascular medical conditions was defined based on a review of the hospital medical record.

Echocardiographic data was available for only 5009 participants

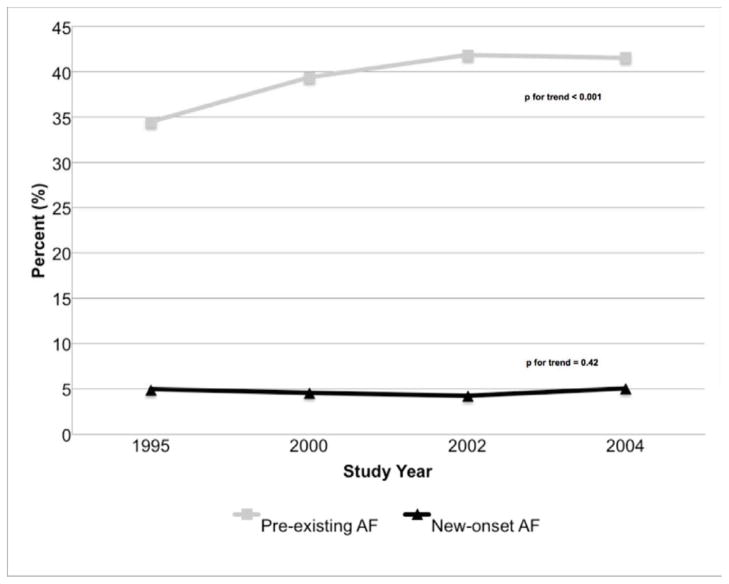

Rates of new-onset AF remained stable between 1995 and 2004 (4.9% to 5.0%), whereas the proportion of patients with pre-existing AF (34.5% to 41.6%) increased during the years under study (Figure 1). In multivariate logistic regression analyses adjusting for potential confounders, the odds of developing new-onset AF during hospitalization for ADHF was 30% higher in 2004 compared to 1995 [OR = 1.30, 95% CI 0.96, 1.77] and the odds of presenting with a history of AF was nearly 50% higher in 2004 than in 1995 (OR = 1.42, 95% CI 1.24, 1.63).

Figure 1.

Rates of New-Onset and Pre-existing Atrial Fibrillation (AF) in Patients Admitted with Acute Heart Failure by Study Year

Patients admitted for ADHF with a history of AF or new-onset AF were on average older and more likely to be white than were patients with no AF (Table 1). Patients with new-onset AF had lower systolic blood pressure and heart rate, but similar diastolic blood pressure values, to patients with no AF on admission. Patients with pre-existing AF, but not new-onset AF, were more likely to report a history of cardiovascular and non-cardiovascular diseases.

The demographic characteristics of patients with new-onset AF differed little from those with pre-existing AF, but those with new-onset AF had a lower burden of comorbid disease and a poorer hemodynamic profile on hospital presentation (Table 1). Likely reflecting the lower prevalence of diabetes and obesity among patients with pre-existing and new-onset AF, both groups had lower admission blood glucose and total cholesterol levels than did patients with no prior AF.

The treatment of patients with ADHF and either new-onset or pre-existing AF was significantly different from those with no AF (Table 2). Individuals with new-onset and pre-existing AF were less likely to have been prescribed aspirin, nitrates, or statins, but were more likely to have received digoxin, amiodarone or anticoagulants (over half were prescribed warfarin) while hospitalized for ADHF. Patients with any type of AF were less likely to have undergone percutaneous coronary revascularization but were more likely to have received a permanent pacemaker than those with no AF. The use of evidence-based HF medications differed little between ADHF patients with pre-existing and new-onset AF (Table 2). Patients developing AF in-hospital were more commonly prescribed heparin, but were less commonly prescribed warfarin or amiodarone, than those with pre-existing AF. Notably, patients with pre-existing AF were less likely to have undergone percutaneous coronary intervention than those with new-onset AF.

Table 2.

In-Hospital Treatment Practices in Patients with Acute Heart Failure According to the presence and type of Atrial Fibrillation (AF)

| Treatment | New-Onset AF (n=449) | P Value (New vs. No) | Pre-existing AF (n=3868) | P Value (Pre vs. No) | No AF (n=5431) | P Value (New vs. Pre) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| In-Hospital Medications | ||||||

| Aspirin | 239 (53.2%) | <0.001 | 1922 (49.7%) | <0.001 | 3325 (61.2%) | 0.16 |

| Beta-blocker | 249 (55.5%) | 0.78 | 2163 (55.9%) | 0.27 | 2974 (54.8%) | 0.85 |

| Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor | 220 (49.0%) | 0.18 | 1960 (50.7%) | 0.12 | 2841 (52.3%) | 0.50 |

| Angiotensin receptor blocker | 22 (4.9%) | 0.52 | 264 (6.8%) | <0.05 | 305 (5.6%) | 0.12 |

| Statin | 100 (22.3%) | <0.01 | 1022 (26.4%) | <0.05 | 1541 (28.4%) | 0.05 |

| Digoxin | 257 (57.2%) | <0.001 | 2382 (61.6%) | <0.001 | 1603 (29.5%) | 0.08 |

| Nitrate | 244 (54.3%) | 0.09 | 2136 (55.2%) | <0.01 | 3177 (58.5%) | 0.72 |

| Diuretic | 439 (97.8%) | 0.34 | 3757 (97.1%) | 0.75 | 5269 (97.0%) | .042 |

| Amiodarone | 31 (6.9%) | <0.05 | 471 (12.2%) | <0.001 | 193 (3.6%) | <0.01 |

| Anticoagulants | 314 (69.9%) | <0.001 | 2891 (74.7%) | <0.001 | 3002 (55.3%) | <0.05 |

| Coumadin | 183 (40.8%) | <0.001 | 2040 (52.7%) | <0.001 | 616 (11.3%) | <0.001 |

| Heparin | 206 (45.9%) | 0.59 | 1316 (34.0%) | <0.001 | 2420 (44.6%) | <0.001 |

| Enoxaparin | 49 (10.9%) | <0.001 | 317 (8.2%) | <0.01 | 352 (6.5%) | 0.06 |

| Procedures | ||||||

| Percutaneous coronary intervention | 25 (5.6%) | 0.23 | 134 (3.5%) | <0.001 | 381 (7.0%) | <0.05 |

| Coronary artery bypass graft | 2 (0.5%) | 0.32 | 15 (0.4%) | <0.01 | 46 (0.9%) | 0.86 |

| Intra-aortic balloon pump | 1 (0.2%) | 0.94 | 6 (0.2%) | 0.37 | 13 (0.2%) | 0.75 |

| Permanent Pacemaker | 11 (2.5%) | <0.05 | 92 (2.4%) | <0.001 | 63 (1.2%) | 0.93 |

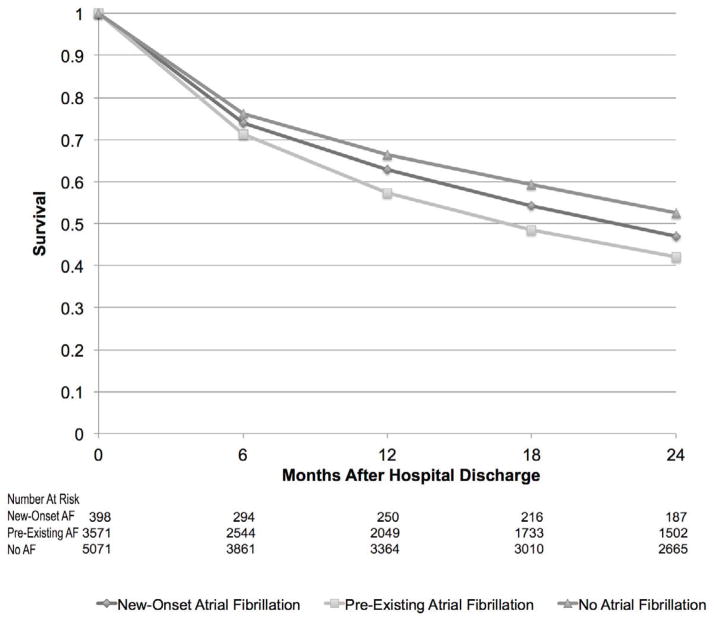

Patients admitted with ADHF and either pre-existing or new-onset AF had higher in-hospital and post-discharge mortality rates than did those with no AF (Figure 2). After adjustment for differences in factors known to influence the prognosis of patients with ADHF, patients with new-onset AF remained nearly 70% more likely to die during their index hospitalization, whereas patients with pre-existing AF were at 30% higher odds of dying at 1 and 2-years after hospital discharge, compared to patients without AF (Table 3).

Figure 2.

Post-Discharge Survival in Patients with New-Onset, Pre-Existing, and No Atrial Fibrillation During Hospitalization for Acute Heart Failure

Table 3.

In-hospital, 1-year, and 2-year Post-Discharge Death Rates among Patients Hospitalized with Acute Heart Failure According to the Presence and Type of Atrial Fibrillation (AF)

| Atrial Fibrillation | In-hospital deaths | Adjusted Odds of Death (95% CI) | 1-year deaths | Adjusted Odds of Death (95% CI) | 2-year deaths | Adjusted Odds of Death (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| None | 358 (6.6%) | REFERENT | 1708 (33.7%) | REFERENT | 2404 (47.4%) | REFERENT |

| Previous | 295 (7.6%) | 1.07 (0.91, 1.26) | 1523 (42.6%) | 1.28 (1.17, 1.40) | 2069 (57.9%) | 1.30 (1.19, 1.42) |

| New Onset | 51 (11.4%) | 1.66 (1.22, 2.27) | 148 (37.2%) | 1.01 (0.81, 1.25) | 211 (53.0%) | 1.07 (0.87, 1.32) |

Adjusted for age (per year increase), sex, study period

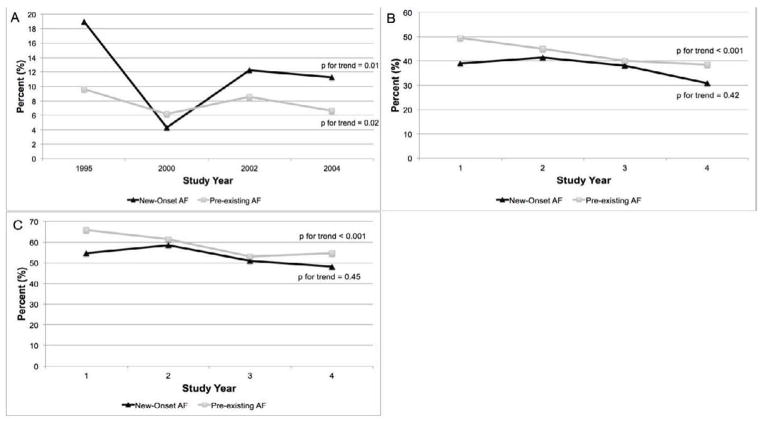

In-hospital, as well as 1 and 2-year post-discharge death rates, improved during the years under study in patients with pre-existing AF (Figure 3). Although in-hospital CFRs declined, post-discharge death rates did not change significantly over the study period among patients with new-onset AF (Figure 3). In multivariable logistic regression models adjusting for potentially confounding factors, we observed no significant change over time in the odds of dying among those with new-onset AF (Table 4) between 1995 and 2004. In contrast, we noted a steady decline in the odds of dying during hospitalization and in the 2 years after discharge in patients with pre-existing AF during this period (Table 4).

Figure 3.

In-Hospital, 1-Year, and 2-Year Post-Discharge Death Rates in Patients with New-Onset and Pre-Existing AF During Hospitalization for Acute Heart Failure by Study Year (A=In-Hospital; B = 1-Year Post-Discharge; C = 2-Years Post-Discharge).

Table 4.

Trends in the Adjusted* Odds of In-Hospital, 1-year, and 2-year Post-Discharge Death Among Patients with New-onset and Pre-existing Atrial Fibrillation

| Study Year | Adjusted Odds of In-Hospital Death | Adjusted Odds of Death at 1-Year | Adjusted Odds of Death at 2-Years | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-Existing AF | New-Onset AF | Pre-Existing AF | New-Onset AF | Pre-Existing AF | New-Onset AF | |

| 1995 | REFERENT | REFERENT | REFERENT | REFERENT | REFERENT | REFERENT |

| 2000 | 0.56 (0.39, 0.83) | 0.24 (0.08, 0.74) | 0.63 (0.56, 0.88) | 1.52 (0.75, 3.10) | 0.67 (0.53, 0.84) | 1.73 (0.85, 3,55) |

| 2002 | 0.80 (0.56, 1.14) | 0.69 (0.29, 1.65) | 0.54 (0.43, 0.67) | 0.76 (0.36, 1.57) | 0.44 (0.35, 0.56) | 0.64 (0.31, 1.34) |

| 2004 | 0.53 (0.35, 0.78) | 0.69 (0.28, 1.67) | 0.47 (0.38, 0.60) | 1.06 (0.50, 2.26) | 0.46 (0.46, 0.58) | 1.17 (0.56, 2.46) |

Adjusted for age, sex, race, length of stay, history of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, stroke, anemia, diabetes, coronary heart disease, coronary artery bypass graft, as well as admission systolic and diastolic blood pressures, heart rate, creatinine, and glucose.

Discussion

Within a community-based cohort of almost 10,000 patients hospitalized with ADHF over a nearly decade long period, we demonstrated that pre-existing and new-onset AF are common in these ill patients and that the proportion of patients hospitalized with pre-existing AF and HF is increasing.

AF and HF frequently coexist, have similar risk factors, and each condition predisposes to the other.21 Estimates on the prevalence of AF among patients hospitalized with AF vary (15–35%), but a recent analysis of administrative data from over 90,000 admissions for HF between 2005 and 2010 showed that nearly 1 in 3 hospitalized ADHF patients had AF.22 We observed high rates of pre-existing AF and showed an increase in the proportion of patients admitted for ADHF with known AF. Since both HF and AF are associated with advancing age, it is likely that the increasing numbers of older patients admitted with ADHF are contributing to the higher rates of pre-existing AF seen in our sample over time.23

Few data are available on the rates of, or recent trends in, new-onset AF complicating ADHF. Most cases of AF occur in the first 12-months after HF diagnosis and the incidence of AF in outpatients with HF is estimated to be 44 per 1000 patient-years.18 We observed that 1 in 20 patients admitted with ADHF had new-onset AF on presentation or developed AF during their index hospitalization. Consistent with a prior report showing that patients with new-onset AF were more likely to be hospitalized for a longer duration than patients who did not develop AF,22 individuals with ADHF and new-onset AF in our study were, on average, hospitalized for 1.5 days longer than those without AF. Similar to the findings of 2 prior HF clinical trials and a community-based investigation involving 1,664 individuals with HF, we observed that new-onset AF in patients with ADHF was associated with a nearly two-thirds higher-odds of dying during hospitalization.6,17,24,25

Although a recent investigation showed that optimally treated outpatients who had a history of AF and developed HF had similar survival rates to patients with HF alone,15 we observed poorer 1 and 2-year survival rates among patients with AF at the time of their HF diagnosis. Perhaps due to the older age and higher comorbid disease burden of “real-world” patients enrolled in our study compared to those presenting to specialty HF clinics,26 rates of adherence to evidence-based HF therapies were low in participants with and without AF. When viewed in light of recent data suggesting an incremental reduction in risk of dying associated with increased use of guideline-based HF therapies in patients with AF,27 the persistent relation between AF and long-term death rates in ADHF might be abrogated with higher use of evidence-based HF therapies.

Whereas pre-existing AF was associated with reduced post-discharge survival, new-onset AF was not. Although we enrolled comparatively few patients with new-onset AF, our findings suggest that presentation with, or development of, AF in the context of ADHF may contribute to in-hospital course but not necessarily long-term prognosis. Our observation stands in contrast to the findings of a recent study showing that patients with AF at the time of their HF diagnosis have better long-term survival rates as compared with those developing AF after their HF diagnosis.16 Reasons for the discrepant nature of these findings may be due to relatively small sample sizes or under-diagnosis of AF in prior studies; it is notable that our results are consistent with the larger and rigorously adjudicated events included among patients with AF and HF enrolled in the SOLVD study.25

We observed a decrease over time in the odds of dying in patients with ADHF and pre-existing, but not new-onset, AF during the study period. Although we did not examine or adjust for changes over time in the treatment of patients admitted with AF and ADHF, our findings suggest that efforts to improve the inhospital observation and treatment of patients with ADHF and AF may be having a beneficial effect on mortality rates in these high-risk patients.

Acknowledgments

Grant Support: Grant support for this project was provided by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (R01 HL69874).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Lloyd-Jones DM, Larson MG, Leip EP, Beiser A, D’Agostino RB, Kannel WB, Murabito JM, Vasan RS, Benjamin EJ, Levy D. Lifetime risk for developing congestive heart failure: The Framingham heart study. Circulation. 2002;106:3068–3072. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000039105.49749.6f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lloyd-Jones DM, Wang TJ, Leip EP, Larson MG, Levy D, Vasan RS, D’Agostino RB, Massaro JM, Beiser A, Wolf PA, Benjamin EJ. Lifetime risk for development of atrial fibrillation: The Framingham heart study. Circulation. 2004;110:1042–1046. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000140263.20897.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Steinberg JS. Atrial fibrillation: An emerging epidemic? Heart. 2004;90:239–240. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2003.014720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wolf PA, Abbott RD, Kannel WB. Atrial fibrillation as an independent risk factor for stroke: The Framingham study. Stroke. 1991;22:983–988. doi: 10.1161/01.str.22.8.983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Benjamin EJ, Wolf PA, D’Agostino RB, Silbershatz H, Kannel WB, Levy D. Impact of atrial fibrillation on the risk of death: The Framingham heart study. Circulation. 1998;98:946–952. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.98.10.946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang TJ, Larson MG, Levy D, Vasan RS, Leip EP, Wolf PA, D’Agostino RB, Murabito JM, Kannel WB, Benjamin EJ. Temporal relations of atrial fibrillation and congestive heart failure and their joint influence on mortality: The Framingham heart study. Circulation. 2003;107:2920–2925. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000072767.89944.6E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lubitz SA, Benjamin EJ, Ellinor PT. Atrial fibrillation in congestive heart failure. Heart Fail Clin. 6:187–200. doi: 10.1016/j.hfc.2009.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fonarow GC, Corday E. Overview of acutely decompensated congestive heart failure (adhf): A report from the adhere registry. Heart Fail Rev. 2004;9:179–185. doi: 10.1007/s10741-005-6127-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Greenlee RT, Vidaillet H. Recent progress in the epidemiology of atrial fibrillation. Curr Opin Cardiol. 2005;20:7–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goldberg RJ, Darling C, Joseph B, Saczynski J, Chinali M, Lessard D, Pezzella S, Spencer FA. Epidemiology of decompensated heart failure in a single community in the northeastern united states. Am J Cardiol. 2009;104:377–382. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2009.03.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goldberg RJ, Ciampa J, Lessard D, Meyer TE, Spencer FA. Long-term survival after heart failure: A contemporary population-based perspective. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:490–496. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.5.490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ghali JK, Cooper R, Ford E. Trends in hospitalization rates for heart failure in the united states, 1973–1986. Evidence for increasing population prevalence. Arch Intern Med. 1990;150:769–773. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Go AS, Hylek EM, Phillips KA, Chang Y, Henault LE, Selby JV, Singer DE. Prevalence of diagnosed atrial fibrillation in adults: National implications for rhythm management and stroke prevention: The anticoagulation and risk factors in atrial fibrillation (atria) study. JAMA. 2001;285:2370–2375. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.18.2370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carson PE, Johnson GR, Dunkman WB, Fletcher RD, Farrell L, Cohn JN. The influence of atrial fibrillation on prognosis in mild to moderate heart failure. The v-heft studies. The v-heft va cooperative studies group. Circulation. 1993;87:VI102–110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tveit A, Flonaes B, Aaser E, Korneliussen K, Froland G, Gullestad L, Grundtvig M. No impact of atrial fibrillation on mortality risk in optimally treated heart failure patients. Clin Cardiol. 2011;34:537–542. doi: 10.1002/clc.20939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smit MD, Moes ML, Maass AH, Achekar ID, Van Geel PP, Hillege HL, van Veldhuisen DJ, Van Gelder IC. The importance of whether atrial fibrillation or heart failure develops first. Eur J Heart Fail. 2012;14:1030–1040. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hfs097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dries DL, Exner DV, Gersh BJ, Domanski MJ, Waclawiw MA, Stevenson LW. Atrial fibrillation is associated with an increased risk for mortality and heart failure progression in patients with asymptomatic and symptomatic left ventricular systolic dysfunction: A retrospective analysis of the solvd trials. Studies of left ventricular dysfunction. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 1998;32:695–703. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(98)00297-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miyasaka Y, Barnes ME, Gersh BJ, Cha SS, Bailey KR, Abhayaratna W, Seward JB, Iwasaka T, Tsang TS. Incidence and mortality risk of congestive heart failure in atrial fibrillation patients: A community-based study over two decades. Eur Heart J. 2006;27:936–941. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maisel WH, Stevenson LW. Atrial fibrillation in heart failure: Epidemiology, pathophysiology, and rationale for therapy. Am J Cardiol. 2003;91:2D–8D. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(02)03373-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vasan RS, Benjamin EJ, Levy D. Prevalence, clinical features and prognosis of diastolic heart failure: An epidemiologic perspective. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 1995;26:1565–1574. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(95)00381-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Seiler J, Stevenson WG. Atrial fibrillation in congestive heart failure. Cardiol Rev. 18:38–50. doi: 10.1097/CRD.0b013e3181c21cff. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mountantonakis SE, Grau-Sepulveda MV, Bhatt DL, Hernandez AF, Peterson ED, Fonarow GC. Presence of atrial fibrillation is independently associated with adverse outcomes in patients hospitalized with heart failure: An analysis of get with the guidelines-heart failure. Circ Heart Fail. 2012;5:191–201. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.111.965681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Anter E, Jessup M, Callans DJ. Atrial fibrillation and heart failure: Treatment considerations for a dual epidemic. Circulation. 2009;119:2516–2525. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.821306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee DS, Gona P, Vasan RS, Larson MG, Benjamin EJ, Wang TJ, Tu JV, Levy D. Relation of disease pathogenesis and risk factors to heart failure with preserved or reduced ejection fraction: Insights from the framingham heart study of the national heart, lung, and blood institute. Circulation. 2009;119:3070–3077. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.815944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kober L, Swedberg K, McMurray JJ, Pfeffer MA, Velazquez EJ, Diaz R, Maggioni AP, Mareev V, Opolski G, Van de Werf F, Zannad F, Ertl G, Solomon SD, Zelenkofske S, Rouleau JL, Leimberger JD, Califf RM. Previously known and newly diagnosed atrial fibrillation: A major risk indicator after a myocardial infarction complicated by heart failure or left ventricular dysfunction. Eur J Heart Fail. 2006;8:591–598. doi: 10.1016/j.ejheart.2005.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yancy CW, Fonarow GC, Albert NM, Curtis AB, Stough WG, Gheorghiade M, Heywood JT, McBride ML, Mehra MR, O’Connor CM, Reynolds D, Walsh MN. Influence of patient age and sex on delivery of guideline-recommended heart failure care in the outpatient cardiology practice setting: Findings from improve hf. Am Heart J. 2009;157:754–762. e752. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2008.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fonarow GC, Albert NM, Curtis AB, Gheorghiade M, Liu Y, Mehra MR, O’Connor CM, Reynolds D, Walsh MN, Yancy CW. Incremental reduction in risk of death associated with use of guideline-recommended therapies in patients with heart failure: A nested case-control analysis of improve HF. Journal of the American Heart Association. 2012;1:16–26. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.111.000018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]