Abstract

Depression is one of the most common mental health problems encountered in primary care and a leading cause of disability worldwide. In many cases, depression is a chronic or recurring disease, and as such, it is best managed like a chronic illness. Moreover, medically ill patients with depressive disorder are at greater risk for a chronic course of depression or less complete recovery. Antidepressant medications and psychotherapies can help many if not most depressed individuals, but millions of primary care patients do not receive effective treatment. Effective management of depression in the primary care setting requires a systematic, population-based approach which entails systematic case finding and diagnosis, patient engagement and education, use of evidence-based treatments including medications and / or psychotherapy, close follow-up to make sure patients are improving and a commitment to keep adjusting treatments or consult with mental health specialists until depression is significantly improved. Programs in which primary care providers and mental health specialists collaborate effectively using principles of measurement-based stepped care and treatment to target can substantially improve patients’ health and functioning while reducing overall health care costs.

Introduction

Depression is one of the most common and disabling chronic health problems encountered in the primary care setting. In this article, opportunities and strategies to improve care for depression in primary care practice are reviewed and collaborative care, an evidence-based approach to chronic disease management for depression is introduced. In this approach, primary care providers (PCPs) and care managers look after a caseload of depressed patients with systematic support from mental health experts. Lessons from implementing evidence-based collaborative care programs in diverse primary care practice settings are summarized to convey relatively simple changes that can improve patient outcomes in primary care practices.

The clinical epidemiology of depression in primary care

Behavioral health problems such as depression, anxiety, alcohol or substance abuse are among the most common and disabling health conditions worldwide 1 and common in primary care settings 2-9. Depending on the clinical setting, between 5 and 20 % of adult patients,10, 11 including adolescents,12-14 and older adults15, seen in primary care have clinically significant depressive symptoms. Depression is one of the most common conditions treated in primary care and nearly 10% of all primary care office visits are depression related.16 From 1997 to 2002, the proportion of depression visits that took place in primary care increased from 51% to 64%.17 For many patients, depression is a chronic or recurrent illness.18 For example, up to 40 % of depressed older adults meet criteria for chronic depression.19 And depressed patients with chronic medical illnesses are at greater risk for a chronic course of depression or less complete recovery.20

National surveys have consistently demonstrated that more Americans receive mental health care from primary care providers than from mental health specialists 21, 22 and primary care has been identified as the ‘de facto mental health services system’2, 21 for adults, children, and older adults with common mental disorders.23, 24 Most patients would prefer an integrated approach in which primary care and mental health providers work together to address medical and behavioral health needs.25 In reality, however, we have a fragmented system in which medical, mental health, substance abuse, and social services are delivered in geographically and organizationally separate ‘silos’ with little to no effective collaboration. A recent national survey26 concluded that two thirds of primary care providers reported that they could not get effective mental health services for their patients. Barriers to mental health care access included shortage of mental health care providers, and lack of insurance coverage.

Interaction of depression with other chronic illnesses

Successful management of depression in primary care settings is particularly important considering complex interactions between mental and physical health27. Major depression is associated with high numbers of medically unexplained symptoms 28-30, such as pain and fatigue, and poor general health outcomes1, 31. Untreated depression is independently associated with morbidity31-34, delayed recovery and negative prognosis among those with medical illness, elevated premature mortality associated with comorbid medical illness 35 and increased health care costs 36-38. Depression also increases functional impairment 39-44 and decreases work productivity 45. Depression significantly decreases quality of life for patients and their family members 46, 47. In a study of 2,558 elderly primary care patients, participants with depression had greater losses in quality adjusted life years (QALYs) than those with emphysema, cancer, chronic foot problems, or hypertension47. Depression can also be a barrier to positive and productive relationships between patients and providers48, 49. PCPs tend to rate patients with depression as more difficult to evaluate and treat compare to those without depression 48 and depressed patients have been shown to be less satisfied with their PCPs49.

Screening/Diagnosing Depression

Depression in primary care is underdetected, underdiagnosed, and undertreated. Older adults, men, patients with medical comorbidities, and patients from ethnic minority groups are at particularly high risk of not being recognized as depressed or treated effectively.50-54 The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) issued recommendations, encouraging primary care physicians to routinely screen their adult patients for depression in clinical settings that have systems in place to assure effective treatment and follow up 55.

Brief screening tools for depression are available. A simple question ‘Do you often feel sad or depressed?’ to which the patient is required to answer either ‘yes’ or ‘no’ was tested in a sample of medically ill patients in the community and had a sensitivity of 69% and a specificity of 90% 56. The Patient Health Questionaire-2 (PHQ-2) consists of two questions about depressed mood: (a) ‘during the past weeks have you often been bothered by feeling down, depressed, or hopeless?’ And (b) ‘during the past month have you often been bothered by little interest or pleasure in doing things.’57 Such brief screening tools can be easily administered by office staff or physicians during a primary care visit. Positive response to these questionnaires should alert the primary care provider to further evaluate the patient for depression. Not all depressed patients will answer positively to these questionnaires. To address the possible ‘false negatives,’ clinicians may wish to ask additional questions about depressive symptoms for patients who appear depressed, who have a difficulty engaging in care, or whose functional impairment seems inconsistent with objective medical illness.

Treatment of depression

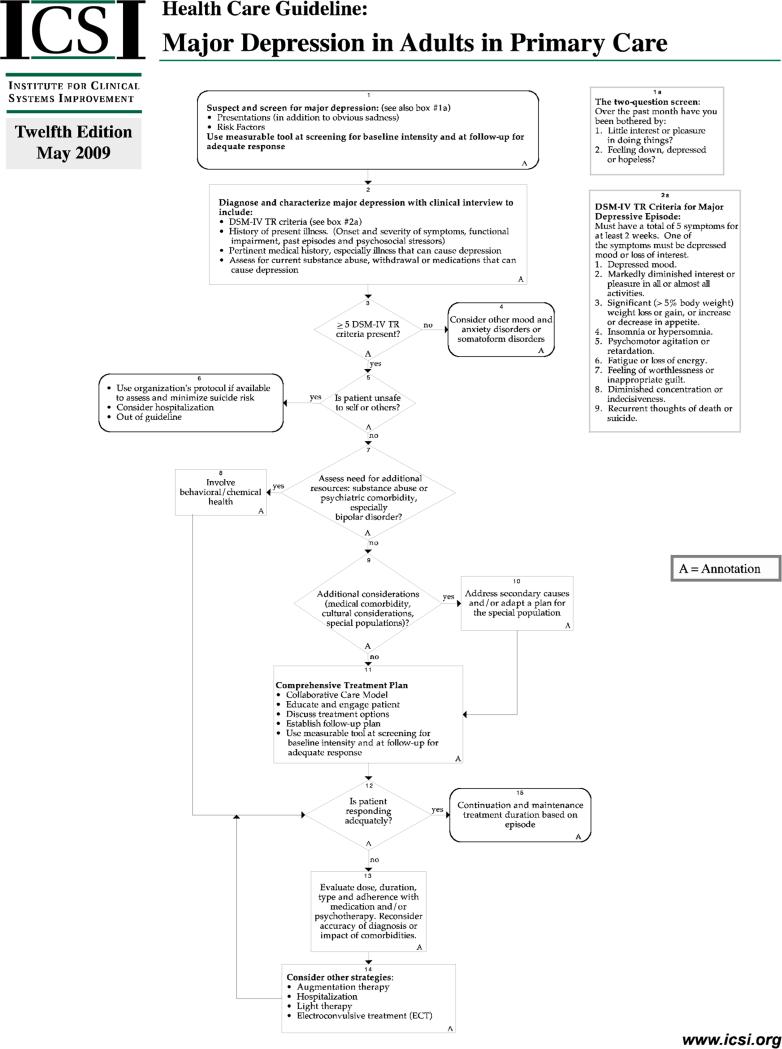

Over 25 medications have been approved by the FDA for the treatment of major depression and there is strong and increasing evidence about the effectiveness of psychotherapies that can be delivered in primary care or specialty mental health care settings 58-60. A number of guidelines have been developed to guide the effective management of depression in primary care 61 and in specialty mental health settings.62 These guidelines succinctly summarize the evidence-base for pharmacological and nonpharmacological treatment options. If nonpharmacologic treatments are available, PCPs should ask patients who are initiating depression treatment about preferences for medications or psychotherapy because the ability to address a patient's treatment preference has been shown to be related to the likelihood of entering depression treatment 63 and better treatment outcomes 64. Patients’ clinical outcomes should be tracked with structured depression rating scales, such as the 9-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9), similar to the way primary care providers follow clinical outcomes of other treatments such as blood pressures or blood lipids. Treatments should be systematically adjusted for patients who do not improve with initial treatments using evidence-based medication treatments and/or psychotherapies. The flowchart in Figure 1 summarizes a comprehensive guideline for the treatment of major depression in primary care developed by the Institute of Clinical Systems Improvement (ICSI).65

Figure 1.

ICSI Guideline for Major Depression in Adults in Primary Care

Effective management of depression in primary care requires a number of steps: detection and diagnosis, patient education and engagement in treatment, initiation of evidence-based pharmacotherapy or psychotherapy, close follow-up focusing on treatment adherence, treatment effectiveness, and treatment side effects. Consistent follow up is crucial as treatment adherence is a major problem in primary care. Response to specific depression treatments varies among individuals and data from large treatment trials in primary care and specialty care settings point out that initial treatments are effective in about 30 – 50 % of patients regardless of the choice of initial pharmacotherapy or psychotherapy.63, 66-68

There is little information to guide initial selection of treatments except for treatment history in patients and family members. Clinicians should follow existing guidelines and take into account patient's treatment preferences when selecting initial treatments. Perhaps most importantly, they should be prepared to adjust and intensify treatment for the 50 – 70 % of patients who will not improve with initial treatment.69 Data from the Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression (STAR-D) trial indicates that the majority of patients who failed an initial trial of an antidepressant medication improved with sequential adjustments in dose, agent, or both in treatment.70 Patients with particularly challenging cases of depression (i.e. those who do not respond to several treatment adjustments, patients with comorbid psychiatric problems such as psychosis, or patients considered to be at high risk for self harm) should be considered for a psychiatric consultation or referral to specialty mental health care for additional treatments such as inpatient treatment and electroconvulsive therapy.

Quality of care for depression

There is a large gap between the efficacy of treatments for depression under research conditions and the effectiveness of treatments as they occur in the “real world” primary care settings 71. Although a number of effective pharmacological and nonpharmacological treatments exist for depression, studies in the United States and Canada have consistently demonstrated that few patients receive adequate doses or courses of such treatments.50, 72-74 Almost 30 million Americans receive prescriptions for antidepressants each year, which are most often prescribed by primary care providers. Unfortunately many patients stop medication early because of side effects or other concerns and do not follow up with their primary care provider to change treatments. Few patients have access to or use evidence-based psychotherapies in primary care settings. Others continue on ineffective doses and medications due to clinical inertia75 and a lack of appropriate treatment intensification in patients who are not improving with initial treatments. As a result, as few as 20 – 40 % of patients started on depression treatment in primary care show substantial clinical improvements.76, 77 Similar problems have been identified for patients treated in specialty mental health care settings78, but patients treated in specialty settings often have greater severity of illness and receive treatment that is more consistent with existing guidelines. Patients referred to psychotherapy often receive inadequate trials of such treatments and treatment response rates can be as low as 20 %.79 Barriers include limited availability of evidence-psychotherapy and costs.

Time constraints and conflicting demands in ‘real-world’ primary care settings are a major challenge for effectively treating depression in primary care settings 80. Generalist physicians also have limited training in the diagnosis and treatment of depression and other mental illnesses. Patients may feel reluctance to discuss their emotional distress, family problems, or behavioral problems with primary care providers because of the stigma associated with mental disorders and concerns that the PCP might not take their other health problems seriously.

Strategies to improve the management of depression in primary care

Efforts to improve the management of depression and other common mental disorders in primary care have focused on screening, education of primary care providers, development of treatment guidelines, and referral to mental health specialty care. Although well intended, these efforts have by and large not been effective in reducing the substantial burden of depression and other common mental disorders in primary care.81 Another approach to improve care for patients with depression is to co-locate mental health specialists into primary care clinics. Having a mental health professional such as a psychologist, a clinical social worker, or a psychiatrist available to see patients in primary care can improve access to mental health services but there is little evidence that such co-location of a behavioral health provider in primary care by itself is sufficient to improve patient outcomes for large populations of primary care patients.82

Collaborative Care and Stepped Care

Over the past 15 years, more than 40 randomized controlled trials have established a robust evidence base for an approach called ‘collaborative care for depression’83-85. More recent studies have documented the effectiveness of such collaborative approaches for anxiety disorders 86 and for depression and comorbid medical disorders such as diabetes and heart disease 87. In such programs, primary care providers are part of a collaborative care team that a depression care manager (usually a nurse or clinical social worker and in some cases a trained medical assistant under supervision from a mental health provider) and a designated psychiatric consultant to augment the management of depression in the primary care setting. The depression care manager supports medication management prescribed by PCPs through patient education, close and pro-active follow-up, and brief, evidence-based psychosocial treatments such as behavioral activation or problem solving treatment in primary care. The care manager may also facilitate referrals to additional services as needed. A designated psychiatric consultant regularly (usually weekly) reviews all patients in the care manager's caseload who are not improving as expected and provides focused treatment recommendations to the patient's PCP. The psychiatric consultant is also available to the care manager and the PCP for questions about patients.83, 88-90 Table 1 summarizes key roles and tasks of the two new team members, the depression care manager and the psychiatric consultant.

Table 1.

Key Processes and Roles for Collaborative Care Team Members

| PROCESS | ROLE | |

|---|---|---|

| Depression Care Manager | Psychiatric Consultant | |

| 1. Systematic diagnosis and tracking of patient outcomes | Patient engagement, education / self management support Close follow-up to make sure patients don't “fall through the cracks” |

Systematic caseload review. Diagnostic consultation on difficult cases |

| 2. Stepped Care a)Change treatment according to evidence-based algorithm if patient is not improving b)Relapse prevention once patient is improved |

Support medication management by primary care provider (PCP) Brief counseling (e.g., behavioral activation or problem-solving treatment in primary care) Facilitate treatment change / referral to mental health as needed Relapse prevention planning |

Consultation focused on patients not improving as expected Recommendations to PCP for additional treatment or referral to specialty care |

From Advancing Integrated Mental Health Solutions (AIMS) Center Website, with permission

Effective collaborative care adhere to the principle of stepped care in which treatment is systematically changed, intensified, or ‘stepped up’ if patients are not improving as expected (e.g., 8-10 weeks after the initiation of evidence-based pharmacotherapy)91. Stepped care approaches can enhance the cost-effectiveness of depression care by focusing the use of limited resources such as care management and specialist consultation on those patients who cannot be effectively managed by the primary care provider alone. Patients initiating care are educated on this systematic approach to treatment and provided tools such as a 9-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9)92, 93 that help them track symptoms of depression over time. They are also encouraged and empowered to request changes in treatment if treatments are not effective or cause significant side effects. Patients who continue to have depressive symptoms after initial treatment trials with medication or psychotherapy are systematically reviewed with a psychiatric consultant and considered for additional treatments as summarized in table 2.

Table 2.

Stepped-care Activities for Depression in Evidence-based Collaborative Care Programs

| Stepped Care Activity | Depression | Local Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Patient Identification / Screening | Provider Referral or screening with PHQ-2 / PHQ-9. | •Who provides key treatment components: primary care provider, mental health staff in primary care, care manager, other? •Where are treatments provided? (e.g., what can happen in primary care clinic vs in referral center) •How do team members communicate & collaborate effectively? •Who is responsible for tracking patient and program outcomes? •How is psychiatric caseload consultation provided? •What kind of training and ongoing clinical support is needed for the program to succeed? |

| Patient Education and Engagement | Patient education. Shared goal setting. Screening for bipolar disorder and substance use. |

|

| Close Follow-up and Behavioral Activation | Close telephone or in-person follow-up. Support of medical management. Behavioral activation strategies used at each contact. |

|

| Medication Management prescribed by primary care provider with guidance from psychiatric consultant | Antidepressant medications. Anxiolytics and Hypnotics as clinically indicated. |

|

| Evidence-based psychotherapy. | Problem-Solving Treatment in Primary Care (PST-PC) or other evidence-based psychotherapy (e.g cognitive behavioral therapy or interpersonal therapy). | |

| Community-based resources | Local community-based resources and support services | |

| Specialty Mental Health / Substance Abuse Referral and Treatment | Mental Health specialty care for severe or persistent depression or comorbidities (e.g., suicidal, dual diagnosis, psychotic). |

From Advancing Integrated Mental Health Solutions (AIMS) Center Website, with permission

Because of the high risk of depression relapse 94, patients who have responded to treatment receive relapse prevention plans that help them maintain treatment gains made. Such relapse prevention plans include advice on the continuation of maintenance medications as clinically indicated, personal warning signs if depression should recur, strategies to maintain clinical gains made (e.g., continued systematic scheduling of pleasant events), and advice on what to do if depression symptoms should recur. Relapse prevention may be particularly important in patients with co-morbid medical conditions who are at higher risk for relapse than those with depression only 20

Research Evidence for Collaborative Care

Studies of collaborative care programs have been conducted in small and large primary care practices, in diverse health care settings under fee-for-service or capitated payment arrangements, with different patient populations including both insured and uninsured / safety net populations, and with different mental health conditions including depression83, 85 and anxiety disorders.95 The literature has consistently demonstrated that collaborative management of depression in primary care is more effective than usual primary care.83, 96

In the largest trial of collaborative care to date, the study entitled ‘Improving Mood – Promoting Access to Collaborative Treatment for Late-Life Depression (IMPACT)’, 1,801 primary care patients with depression and an average of 3.5 chronic medical disorders from 18 primary care clinics in five states were randomly assigned to a collaborative stepped care program or to care as usual. IMPACT participants were more than twice as likely as those in usual care to experience a substantial improvement (a 50% or greater improvement in the depression severity score of the Hopkins Symptom Checklist (SCL-20) over 12 months.76 They also had less physical pain, better social and physical functioning, and better overall quality of life than patients in care as usual 97. Patients and providers participating in collaborative were more satisfied than those in usual care group.98 More recent studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of the IMPACT program in depressed adolescents,99 depressed cancer patients100, 101 and diabetics,102, 103 including low income Spanish speaking patients.104

Long-term cost effectiveness analyses from the IMPACT study found that patients who received collaborative care for depression had substantially lower overall health care costs than those in usual care.105 An initial ‘investment’ in 12 months of collaborative care of approximately $522 resulted in savings in total health care costs of $3,363. Similar cost savings have been identified in other collaborative care trials in patients with depression and diabetes103 and other chronic medical conditions, and in patients with severe anxiety (panic disorder)106. Large scale implementations outside of research trials in several large health care systems such as Kaiser Permanente107 and Intermountain Healthcare108 also point to savings in overall health care costs when collaborative care is effectively implemented. Collaborative care interventions also generate important social benefits in terms of quality adjusted life years.109 Finally, and perhaps most importantly, collaborative care has been shown to improve both patient76 and provider98 satisfaction with care.

Collaborative care programs such as the approach tested in IMPACT have been recommended as an evidence-based practice by the Substance Abuse & Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) and recommended as a “best practice” by the Surgeon General's Report on Mental Health110, the President's New Freedom Commission on Mental Health111, and a number national organizations including the National Business Group on Health112. In a recent evidence-based practice report by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality AHRQ that reviewed the existing literature on approaches to Integration of Mental Health/Substance Abuse and Primary Care, the IMPACT program was profiled as one of the most successful models of integrated mental health care to date.113

Large Scale Implementations of Collaborative Care

Although there are some variations in the components of collaborative care programs, most effective programs build on several core clinical principles and components. These include the core components of chronic illness care as proposed by Wagner and colleagues114: (a) the use of explicit treatment plans and protocols; (2) the reorganization of the practice to meet the needs of patients who require more time, a broad array of resources, and closer follow-up; (3) systematic attention to the information and behavioral change needs of patients (4) ready access to necessary expertise (5) supportive information systems and strategies such as ‘measurement-based care,’115 ‘treatment to target,’ and ‘stepped care.’91 Systematic measurement of clinical outcomes using brief, patient-rating scales such as the 9-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) for depression92 helps clinicians keep track if patients are improving as expected or if treatment needs to be adjusted. On the PHQ9, a drop in 5 points has been identified as a clinically meaningful reduction in symptoms but the ultimate treatment target is remission, which is captured by a PHQ-9 score less than 5.116 Psychiatric consultation, a limited resource in most settings can then be focused on patients who are not improving as expected. Such systematic ‘treatment to target’ can overcome the ‘clinical inertia’75 that is often responsible for ineffective treatments of common mental disorders in primary care.

Several health care organizations have undertaken large-scale implementations of evidence-based collaborative care programs for depression. These include national health plans such as Kaiser Permanente, the Depression Improvement Across Minnesota, Offering a New Direction (DIAMOND) program in Minnesota in which the Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement (ICSI) has worked with 8 commercial health plans, 25 medical groups, and over 80 primary care clinics to implement collaborative care for depression 117, 118. In the State of Washington, the Mental Health Integration Program (MHIP) sponsored by the Community Health Plan of Washington and Seattle King County Public Health120 includes more than 100 community health centers and over 30 community mental health centers that work together to provide integrated care for poor, underserved, uninsured or underinsured clients with medical and behavioral health needs. Other large-scale implementations include the Army's Re-Engineering Systems of Primary Care Treatment in the Military (RESPECT-MIL) program 121, implemented in Army primary care clinics in the US and abroad; and the Department of Veterans Affairs’ Veterans Health Administration 122, which has implemented Collaborative Care in hundreds of primary care clinics across the US.

Implementing Effective Collaborative Care Programs

Over the past 10 years, the Advancing Integrated Mental Health Solutions (AIMS) Center at the University of Washington97 has provided technical assistance and training to more than 5,000 clinicians in over 600 primary care practices to implement effective collaborative care. Below are some key lessons from the implementation of such programs in diverse practice settings.

Fragmented financing streams are an important barrier to integrating mental health and primary care services123, but financial integration does not guarantee clinical integration and practices have to develop effective clinical workflows where primary care providers and supporting mental health providers communicate and collaborate effectively.

Simply co-locating a mental health provider into a primary care setting may improve access to behavioral health care but it does not guarantee improved health outcomes for the large population of primary care patients with mental health needs.

Effective treatment requires a move from episodic acute care in which we provide the equivalent of ‘behavioral health urgent care’ to patients presenting for care to a population-based approach in which all patients with behavioral health needs are systematically tracked until the problem is resolved. A ‘registry’ or clinical tracking system is required to identify patients who are ‘falling through the cracks’ and to support effective stepped care. This can be accomplished using the registry functions of electronic health record systems or a freestanding registry tool 124

Initial treatments (be they pharmacologic or psychosocial) are rarely sufficient to achieve desired health outcomes. Systematic outcome tracking, treatment adjustment, and consultation for patients who are not improving can help achieve the desired health outcomes. This requires systematic caseload review by the treating providers and psychiatric consultation, focusing on patients who are not improving as expected.

For mental health providers, effective collaboration in primary care requires clinical flexibility in both mental health specialist as well as primary care providers mental health providers to be flexible, regular and effective communication with patients’ PCPs, the willingness to be interrupted during therapy sessions, the use of the telephone to reach patients who cannot make clinic appointments and the use of brief, evidence-based therapies such as motivational interviewing, behavioral activation, problem solving, or brief cognitive behavioral therapy that can be provided in the context of a busy primary care practice.

Training mental health specialists and primary care in integrated care are important but not sufficient. Effective implementation requires ongoing support from clinical champions in primary care and behavioral health, financial support, operational support, and a clear set of shared and measureable goals and objectives. As with all efforts to improve chronic illness care, such support may be easier to obtain in large delivery systems and under managed care arrangements than in small fee-for-service medical practices.

There are many ways to implement effective integrated care for behavioral health problems in primary care. Treatment manuals used in research studies have been ‘translated’ into job descriptions and clear operational manuals that help busy practices implement the program in their unique settings.

Attention to core principles such as measurement-based care and careful tracking of desired outcomes at the patient and clinic level can help make sure that integrated care programs ‘live up to their promise’ as they are implemented in diverse real world settings.

While the full-scale implementation of evidence-based collaborative care programs may be challenging for small to moderate sized primary care practices under current fee-for-service health care financing mechanisms,123 relatively ‘simple’ changes can help practices improve care and gain important experience on the way to becoming a fully integrated patient centered health care home. Such changes include

Routine use of brief, structured rating scales for common mental disorders such as the PHQ-9 for depression to help with screening but more importantly to determine if patients started on treatment are improving as expected.

Incorporation of such behavioral health rating scales into paper or electronic health records, creating a ‘registry’ function that allows PCPs and clinic managers to identify patients who are ‘falling through the cracks’ or not improving as expected.

Stepped care and ‘treatment to target’ in which treatments (medications, psychosocial treatments, or referrals to mental health) are actively changed and adjusted until the desired health outcomes are achieved.

Incorporation of evidence-based motivational interviewing strategies into patient encounters to help engage patients engage in and adhere to effective treatment for behavioral health problems. Both physicians and other office staff can be trained in these techniques.

Training office-based personnel to help perform core support functions of behavioral health care managers such as proactive outreach and tracking of treatment adherence, medication side effects, referrals (if appropriate), and treatment effectiveness.

Development of relationships and ‘shared workflows’ with behavioral health providers that are not simply referrals but include active dialogue and collaboration between the PCP and the behavioral health provider to ensure patients achieve the desired clinical outcomes.

These strategies are highly compatible with approaches to improve patient care and outcomes through patient centered medical homes.

Conclusion

Depression can be effectively treated in primary care settings using an evidence-based collaborative approach in which primary care providers are systematically supported by mental health providers in caring for a caseload of patients. Core components of effective collaborative care programs include a focus on populations of patients identified with depression, measurement-based care, treatment to target, and stepped care in which treatments are systematically adjusted and ‘stepped up’ if patients are not improving as expected. Such an approach can dramatically improve patient satisfaction and health outcomes. These principles of collaborative care are highly consistent with the notion of Patient Centered Medical Homes and Accountable Care and can help effectively position primary care practices for health care reform and coming changes in health care delivery and financing.

Footnotes

Financial disclosure: Authors have nothing to disclose

References

- 1.Moussavi S, Chatterji S, Verdes E, Tandon A, Patel V, Ustun B. Depression, chronic diseases, and decrements in health: results from the World Health Surveys. Lancet. 2007 Sep 8;370(9590):851–858. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61415-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Regier DA, Goldberg ID, Taube CA. The de facto US mental health services system: a public health perspective. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1978 Jun;35(6):685–693. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1978.01770300027002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barrett JE, Barrett JA, Oxman TE, Gerber PD. The Prevalence of Psychiatric Disorders in a Primary Care Practice. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1988 1988 Dec 1;45(12):1100–1106. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1988.01800360048007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ansseau M, Dierick M, Buntinkx F, et al. High prevalence of mental disorders in primary care. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2004;78(1):49–55. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(02)00219-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leon AC, Olfson M, Broadhead WE, et al. Prevalence of Mental Disorders in Primary Care: Implications for Screening. Arch Fam Med. 1995 Oct 1;4(10):857–861. doi: 10.1001/archfami.4.10.857. 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Monahan PO, Löwe B. Anxiety Disorders in Primary Care: Prevalence, Impairment, Comorbidity, and Detection. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2007 Mar 6;146(5):317–325. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-146-5-200703060-00004. 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sherbourne CD, Jackson CA, Meredith LS, Camp P, Wells KB. Prevalence of comorbid anxiety disorders in primary care outpatients. Archives of Family Medicine. 1996;5(1):27–34. doi: 10.1001/archfami.5.1.27. discussion 35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brienza RS, Stein MD. Alcohol Use Disorders in Primary Care. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2002;17(5):387–397. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2002.10617.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Regier DA, Narrow WE, Rae DS, Manderscheid RW, Locke BZ, Goodwin FK. The de Facto US Mental and Addictive Disorders Service System: Epidemiologic Catchment Area Prospective 1-Year Prevalence Rates of Disorders and Services. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1993 1993 Feb 1;50(2):85–94. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1993.01820140007001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Katon W, Schulberg H. Epidemiology of depression in primary care. General hospital psychiatry. 1992;14(4):237–247. doi: 10.1016/0163-8343(92)90094-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zung W, Broadhead W, Roth M. Prevalence of depressive symptoms in primary care. J Fam Pract. 1993;37(4):337–344. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schubiner H, Tzelepis A, Wright K, Podany E. The clinical utility of the safe times questionnaire. Journal of Adolescent Health. 1994;15(5):374–382. doi: 10.1016/1054-139x(94)90260-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Winter LB, Steer RA, Jones-Hicks L, Beck AT. Screening for major depression disorders in adolescent medical outpatients with the Beck Depression Inventory for Primary Care. Journal of Adolescent Health. 1999;24(6):389–394. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(98)00135-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Johnson JG, Harris ES, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW. The patient health questionnaire for adolescents: Validation of an instrument for the assessment of mental disorders among adolescent primary care patients. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2002;30(3):196–204. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(01)00333-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lyness JM, Caine ED, King DA, Cox C, Yoediono Z. Psychiatric Disorders in Older Primary Care Patients. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 1999;14(4):249–254. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1999.00326.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stafford RS, Ausiello JC, Misra B, Saglam D. National Patterns of Depression Treatment in Primary Care. Primary Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2000;2:211–216. doi: 10.4088/pcc.v02n0603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harman JS, Veazie PJ, Lyness JM. Primary Care Physician Office Visits for Depression by Older Americans. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2006;21(9):926–930. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00497.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Klein DN, Shankman SA, Rose S. Ten-year prospective follow-up study of the naturalistic course of dysthymic disorder and double depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2006 May;163(5):872–880. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.5.872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alexopoulos G, Chester JG. Outcomes on geriatric depression. Vol. 8. Elsevier; New York, NY: 1992. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Iosifescu DV, Nierenberg AA, Alpert JE, et al. Comorbid Medical Illness and Relapse of Major Depressive Disorder in the Continuation Phase of Treatment. Psychosomatics. 2004 Oct 1;45(5):419–425. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.45.5.419. 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Regier DA, Narrow WE, Rae DS, Manderscheid RW, Locke BZ, Goodwin FK. The de facto US mental and addictive disorders service system. Epidemiologic catchment area prospective 1-year prevalence rates of disorders and services. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1993 Feb;50(2):85–94. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1993.01820140007001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang PS, Demler O, Olfson M, Pincus HA, Wells KB, Kessler RC. Changing Profiles of Service Sectors Used for Mental Health Care in the United States. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2006 Jul 1;163(7):1187–1198. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.7.1187. 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Burns BJ, Costello EJ, Angold A, et al. Children's mental health service use across service sectors. Health Affairs. 1995 Aug 1;14(3):147–159. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.14.3.147. 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kessler RC, Birnbaum H, Bromet E, Hwang I, Sampson N, Shahly V. Age differences in major depression: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R). Psychological Medicine. 2010;40(02):225–237. doi: 10.1017/S0033291709990213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mauksch LB, Tucker SM, Katon WJ, et al. Mental illness, functional impairment, and patient preferences for collaborative care in an uninsured, primary care population. J Fam Pract. 2001 Jan;50(1):41–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cunningham PJ. Beyond Parity: Primary Care Physicians' Perspectives On Access To Mental Health Care. Health Aff. 2009 May 1;28(3):w490–501. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.3.w490. 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Katon WJ. Clinical and health services relationships between major depression, depressive symptoms, and general medical illness. Biological Psychiatry. 2003;54(3):216–226. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(03)00273-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Simon GE, VonKorff M. Somatization and psychiatric disorder in the NIMH Epidemiologic Catchment Area study. Am J Psychiatry. 1991;148(11):1494–1500. doi: 10.1176/ajp.148.11.1494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Henningsen P, Zimmermann T, Sattel H. Medically Unexplained Physical Symptoms, Anxiety, and Depression: A Meta-Analytic Review. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2003 Jul 1;65(4):528–533. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000075977.90337.e7. 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gureje O, Von Korff M, Simon GE, Gater R. Persistent Pain and Well-being. JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association. 1998 Jul 8;280(2):147–151. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.2.147. 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Van der Kooy K, van Hout H, Marwijk H, Marten H, Stehouwer C, Beekman A. Depression and the risk for cardiovascular diseases: systematic review and meta analysis. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2007;22(7):613–626. doi: 10.1002/gps.1723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Knol M, Twisk J, Beekman A, Heine R, Snoek F, Pouwer F. Depression as a risk factor for the onset of type 2 diabetes mellitus. A meta-analysis. Diabetologia. 2006;49(5):837–845. doi: 10.1007/s00125-006-0159-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mezuk B, Eaton WW, Golden SH. Depression and Type 2 Diabetes Over the Lifespan: A Meta-Analysis. Diabetes Care. 2009 2009 May 1;32(5):e57. doi: 10.2337/dc08-0985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bonnewyn A, Katona C, Bruffaerts R, et al. Pain and depression in older people: Comorbidity and patterns of help seeking. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2009;117(3):193–196. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2009.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cuijpers P, Smit F. Excess mortality in depression: a meta-analysis of community studies. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2002;72(3):227–236. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(01)00413-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Katon WJ, Lin E, Russo J, Unützer J. Increased medical costs of a population-based sample of depressed elderly patients. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2003 Sep;60(9):897–903. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.9.897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Simon G, Ormel J, VonKorff M, Barlow W. Health care costs associated with depressive and anxiety disorders in primary care. Am J Psychiatry. 1995 Mar;152(3):352–357. doi: 10.1176/ajp.152.3.352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Unützer J, Patrick DL, Simon G, et al. Depressive symptoms and the cost of health services in HMO patients aged 65 years and older. A 4-year prospective study. JAMA. 1997 May 28;277(20):1618–1623. doi: 10.1001/jama.1997.03540440052032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wells K, Stewart A, Hayes R, et al. The functioning and well-being of depressed patients. Results from the Medical Outcomes Study. JAMA. 1989;262:914–919. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Alexopoulos GS, Buckwalter K, Olin J, Martinez R, Wainscott C, Krishnan KRR. Comorbidity of late life depression: an opportunity for research on mechanisms and treatment. Biological Psychiatry. 2002;52(6):543–558. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(02)01468-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kessler RC, Ormel J, Demler O, Stang PE. Comorbid Mental Disorders Account for the Role Impairment of Commonly Occurring Chronic Physical Disorders: Results From the National Comorbidity Survey. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine. 2003;45(12):1257–1266. doi: 10.1097/01.jom.0000100000.70011.bb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Barry LC, Allore HG, Bruce ML, Gill TM. Longitudinal Association Between Depressive Symptoms and Disability Burden Among Older Persons. The Journals of Gerontology Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences. 2009 Dec 1;64A(12):1325–1332. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glp135. 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ciechanowski PS, Katon WJ, Russo JE. Depression and Diabetes: Impact of Depressive Symptoms on Adherence, Function, and Costs. Arch Intern Med. 2000 Nov 27;160(21):3278–3285. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.21.3278. 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lin EHB, Katon W, Von Korff M, et al. Relationship of Depression and Diabetes Self-Care, Medication Adherence, and Preventive Care. Diabetes Care. 2004 Sep 1;27(9):2154–2160. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.9.2154. 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Greenberg PE, Kessler RC, Birnbaum HG, et al. The economic burden of depression in the United States: How did it change between 1990 and 2000? Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2003;64(12):1465–1475. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v64n1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sewitch MJ, McCusker J, Dendukuri N, Yaffe MJ. Depression in frail elders: impact on family caregivers. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2004;19(7):655–665. doi: 10.1002/gps.1135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Unützer J, Patrick DL, Diehr P, Simon G, Grembowski D, Katon W. Quality Adjusted Life Years in Older Adults With Depressive Symptoms and Chronic Medical Disorders. International Psychogeriatrics. 2000;12(01):15–33. doi: 10.1017/s1041610200006177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hahn S, Kroenke K, Spitzer R, et al. The difficult patient. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 1996;11(1):1–8. doi: 10.1007/BF02603477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Callahan E, Bertakis K, Azari R, Robbins J, Helms L, Miller J. The influence of depression on physician-patient interaction in primary care. family medicine. 1996;28(5):346–351. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ettner SL, Azocar F, Branstrom RB, Meredith LS, Zhang L, Ong MK. Association of general medical and psychiatric comorbidities with receipt of guideline-concordant care for depression. Psychiatr Serv. Dec;61(12):1255–1259. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.61.12.1255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gonzalez HM, Vega WA, Williams DR, Tarraf W, West BT, Neighbors HW. Depression care in the United States: too little for too few. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010 Jan;67(1):37–46. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Unützer J, Katon W, Callahan CM, et al. Depression treatment in a sample of 1,801 depressed older adults in primary care. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2003 Apr;51(4):505–514. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51159.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ettner SL, Azocar F, Branstrom RB, Meredith LS, Zhang L, Ong MK. Association of General Medical and Psychiatric Comorbidities With Receipt of Guideline-Concordant Care for Depression. Psychiatric Services. 2010;61(12):1255–1259. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.61.12.1255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mojtabai R, Olfson M. Proportion Of Antidepressants Prescribed Without A Psychiatric Diagnosis Is Growing. Health Affairs. 2011 Aug 1;30(8):1434–1442. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2010.1024. 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.U.S. Preventive Services Task Force [October 30, 2011];Screening for Depression: Recommendations and Rationale. 2002 http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/3rduspstf/depression/depressrr.htm.

- 56.Watkins CL, Lightbody CE, Sutton CJ, et al. Evaluation of a single-item screening tool for depression after stroke: a cohort study. Clinical Rehabilitation. 2007 Sep 1;21(9):846–852. doi: 10.1177/0269215507079846. 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW. The Patient Health Questionnaire-2: Validity of a Two-Item Depression Screener. Medical care. 2003;41(11):1284–1292. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000093487.78664.3C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mynors-Wallis L, Gath D, Day A, Baker F. Randomised controlled trail of problem solving treatment, antidepressant medication, and combined treatment for major depression in primary care. BMJ. 2000;320:26–30. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7226.26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kuyken W, Byford S, Taylor RS, et al. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy to prevent relapse in recurrent depression. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2008;76(6):966–978. doi: 10.1037/a0013786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cuijpers P, van Straten A, Warmerdam L. Behavioral activation treatments of depression: A meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review. 2007;27(3):318–326. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2006.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Inatitute for Clinical Systems Improvement (ICSI). Health Care Guideline: Major Depression in Adults in Primary Care. 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 62.APA working group on major depressive disorder . Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients with Major Depressive Disorder. American Psychiatric Association; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Dwight-Johnson M, Unutzer J, Sherbourne C, Tang L, Wells KB. Can quality improvement programs for depression in primary care address patient preferences for treatment? Med Care. 2001 Sep;39(9):934–944. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200109000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lin P, Campbell D, Chaney E, et al. The influence of patient preference on depression treatment in primary care. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2005;30(2):164–173. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm3002_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.ICSI (Inatitute for Clinical Systems Improvement) Health Care Guideline: Major Depression in Adults in Primary Care. 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 66.Trivedi M, Rush A, Wisniewski S, et al. Evaluation of outcomes with citalopram for depression using measurement-based care in STAR*D: implications for clinical practice. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(1):28–48. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.1.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hansen NB, Lambert MJ, Forman EM. The Psychotherapy Dose-Response Effect and Its Implications for Treatment Delivery Services. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2002;9(3):329–343. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Thase M, Haight B, Richard N, et al. Remission rates following antidepressant therapy with bupropion or selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors: a meta-analysis of original data from 7 randomized controlled trials. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66(8):974–981. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v66n0803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Simon GE, Perlis RH. Personalized Medicine for Depression: Can We Match Patients With Treatments? Am J Psychiatry. 2010 Sep;15 doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.09111680. appi.ajp.2010.09111680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Rush AJ, Trivedi MH, Wisniewski SR, et al. Acute and Longer-Term Outcomes in Depressed Outpatients Requiring One or Several Treatment Steps: A STAR*D Report. Am J Psychiatry. 2006 2006 Nov 1;163(11):1905–1917. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.11.1905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Unutzer J, Katon W, Sullivan M, Miranda J. Treating depressed older adults in primary care: narrowing the gap between efficacy and effectiveness. Milbank Q. 1999;77(2):225–256, 174. doi: 10.1111/1468-0009.00132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Young AS, Klap R, Sherbourne CD, Wells KB. The quality of care for depressive and anxiety disorders in the United States. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2001 Jan;58(1):55–61. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.1.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Duhoux A, Fournier L, Nguyen CT, Roberge P, Beveridge R. Guideline concordance of treatment for depressive disorders in Canada. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2009 May;44(5):385–392. doi: 10.1007/s00127-008-0444-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Wells KB, Schoenbaum M, Unutzer J, Lagomasino IT, Rubenstein LV. Quality of care for primary care patients with depression in managed care. Arch Fam Med. 1999 Nov-Dec;8(6):529–536. doi: 10.1001/archfami.8.6.529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Henke RM, Zaslavsky AM, McGuire TG, Ayanian JZ, Rubenstein LV. Clinical Inertia in Depression Treatment. Medical Care. 2009;47(9):959–967. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31819a5da0. 910.1097/MLR.1090b1013e31819a31815da31810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Unutzer J, Katon W, Callahan CM, et al. Collaborative care management of late-life depression in the primary care setting: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2002 Dec 11;288(22):2836–2845. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.22.2836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Rush AJ, Trivedi M, Carmody TJ, et al. One-year clinical outcomes of depressed public sector outpatients: a benchmark for subsequent studies. Biol Psychiatry. 2004 Jul 1;56(1):46–53. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Simon GE, Von Korff M, Rutter CM, Peterson DA. Treatment process and outcomes for managed care patients receiving new antidepressant prescriptions from psychiatrists and primary care physicians. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2001 Apr;58(4):395–401. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.4.395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Hansen N. The Psychotherapy Dose-Response Effect and its Implications for Treatment Delivery Services. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2002;9:329–343. 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Tai-Seale M, McGuire T, Colenda C, Rosen D, Cook MA. Two-Minute Mental Health Care for Elderly Patients: Inside Primary Care Visits. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2007;55(12):1903–1911. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01467.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Unutzer J, Schoenbaum M, Druss BG, Katon WJ. Transforming Mental Health Care at the Interface With General Medicine: Report for the Presidents Commission. Psychiatr Serv. 2006 2006 Jan 1;57(1):37–47. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.57.1.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Uebelacker LA, Smith M, Lewis AW, Sasaki R, Miller IW. Treatment of depression in a low-income primary care setting with colocated mental health care. Fam Syst Health. 2009 Jun;27(2):161–171. doi: 10.1037/a0015847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Gilbody S, Bower P, Fletcher J, Richards D, Sutton AJ. Collaborative care for depression: A cumulative meta-analysis and review of longer-term outcomes. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:2314–2321. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.21.2314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Simon G. Collaborative care for depression. BMJ. 2006 Feb 4;332(7536):249–250. doi: 10.1136/bmj.332.7536.249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Simon G. Collaborative care for mood disorders. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2009 Jan;22(1):37–41. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e328313e3f0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Roy-Byrne P, Craske MG, Sullivan G, et al. Delivery of Evidence-Based Treatment for Multiple Anxiety Disorders in Primary Care. JAMA. 2010 May 19;303(19):1921–1928. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.608. 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Katon WJ, Lin EHB, Von Korff M, et al. Collaborative Care for Patients with Depression and Chronic Illnesses. New England Journal of Medicine. 2010;363(27):2611–2620. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1003955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Katon W, Unutzer J. Collaborative Care Models for Depression: Time to Move From Evidence to Practice. Arch Intern Med. 2006 Nov 27;166(21):2304–2306. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.21.2304. 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Katon W, Unutzer J, Wells K, Jones L. Collaborative depression care: history, evolution and ways to enhance dissemination and sustainability. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2010 Sep-Oct;32(5):456–464. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2010.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Katon W, Von Korff M, Lin E, Simon G. Rethinking practitioner roles in chronic illness: the specialist, primary care physician, and the practice nurse. General Hospital Psychiatry. 2001 May-Jun;23(3):138–144. doi: 10.1016/s0163-8343(01)00136-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Von Korff M, Tiemens B. Individualized stepped care of chronic illness. Western Journal of Medicine. 2000 Feb;172(2):133–137. doi: 10.1136/ewjm.172.2.133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2001 Sep;16(9):606–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Löwe B, Unützer J, Callahan CM, Perkins AJ, Kroenke K. Monitoring Depression Treatment Outcomes With the Patient Health Questionnaire-9. Medical care. 2004;42(12):1194–1201. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200412000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Kupfer DJ, Frank E, Perel JM, et al. Five-year outcome for maintenance therapies in recurrent depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1992 Oct;49(10):769–773. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1992.01820100013002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Roy-Byrne P, Craske MG, Sullivan G, et al. Delivery of Evidence-Based Treatment for Multiple Anxiety Disorders in Primary Care: A Randomized Controlled Trial. JAMA. 2010 May 19;303(19):1921–1928. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Williams JW, Gerrity M, Holsinger T, Dobscha S, Gaynes B, Dietrich A. Systematic review of multifaceted interventions to improve depression care. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2007;29:91–116. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2006.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.AIMS Cener [Oct 29, 2011];IMPACT Evidence-based depression care. 2011 http://impact-uw.org.

- 98.Levine S, Unutzer J, Yip JY, et al. Physicians' satisfaction with a collaborative disease management program for late-life depression in primary care. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2005 Nov-Dec;27(6):383–391. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2005.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Richardson L, McCauley E, Katon W. Collaborative care for adolescent depression: a pilot study. General Hospital Psychiatry. 2009;31(1):36–45. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2008.09.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Dwight-Johnson M, Ell K, Lee PJ. Can collaborative care address the needs of low-income Latinas with comorbid depression and cancer? Results from a randomized pilot study. Psychosomatics. 2005 May-Jun;46(3):224–232. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.46.3.224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Ell K, Xie B, Quon B, Quinn DI, Dwight-Johnson M, Lee PJ. Randomized controlled trial of collaborative care management of depression among low-income patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008 Sep 20;26(27):4488–4496. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.16.6371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Ell K, Katon W, Xie B, et al. Collaborative care management of major depression among low-income, predominantly Hispanic subjects with diabetes: a randomized controlled trial. Diabetes Care. 2010 Apr;33(4):706–713. doi: 10.2337/dc09-1711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Katon WJ, Russo JE, Von Korff M, Lin EH, Ludman E, Ciechanowski PS. Long-Term Effects on Medical Costs of Improving Depression Outcomes in Patients with Depression and Diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2008 Mar 10; doi: 10.2337/dc08-0032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Gilmer TP, Walker C, Johnson ED, Philis-Tsimikas A, Unutzer J. Improving Treatment of Depression Among Latinos with Diabetes Using Project Dulce and IMPACT. Diabetes Care. 2008 Mar 20; doi: 10.2337/dc08-0307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Unutzer J, Katon WJ, Fan MY, et al. Long-term cost effects of collaborative care for late-life depression. Am J Manag Care. 2008 Feb;14(2):95–100. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Katon WJ, Roy-Byrne P, Russo J, Cowley D. Cost-effectiveness and cost offset of a collaborative care intervention for primary care patients with panic disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2002 Dec;59(12):1098–1104. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.12.1098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Grypma L, Haverkamp R, Little S, Unutzer J. Taking an evidence-based model of depression care from research to practice: making lemonade out of depression. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2006 Mar-Apr;28(2):101–107. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2005.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Reiss-Brennan B, Briot PC, Savitz LA, Cannon W, Staheli R. Cost and quality impact of Intermountain's mental health integration program. J Healthc Manag. Mar-Apr;55(2):97–113. discussion 113-114. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Glied S, Herzog K, Frank R. The Net Benefits of Depression Management in Primary Care. Med Care Res Rev. 2010 Jan;21 doi: 10.1177/1077558709356357. 1077558709356357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services [Oct 30 2011];Mental Health: A Report of the Surgeon General—Executive Summary. 1999 http://www.surgeongeneral.gov/library/mentalhealth.

- 111.New Freedom Commission on Mental Health Achieving the Promise: Transforming Mental Health Care in America, Final Report. 2003 http://store.samhsa.gov/product/SMA03-3831.

- 112.National Business Group on Health [Oct 31, 2011];Engaging Large Employers Regarding Evidence-Based Behavioral Health Treatment. 2010 http://www.businessgrouphealth.org/benefitstopics/et_mentalhealth.cfm.

- 113.Butler M, Kane RL, McAlpine D, et al. Integration of mental health/substance abuse and primary care. Evid Rep Technol Assess (Full Rep) 2008 Nov;(173):1–362. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Wagner EH, Austin BT, Von Korff M. Organizing care for patients with chronic illness. Milbank Quarterly. 1996;74(4):511–544. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Trivedi MH, Daly EJ. Measurement-based care for refractory depression: a clinical decision support model for clinical research and practice. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007 May;88(Suppl 2):S61–71. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Kroenke K, Spitzer R, Williams J. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:606–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement (ICSI). [July 10, 2011]; http://www.icsi.org/health_care_redesign_/diamond_35953/.

- 118.Korsen N, Pietruszewski P. Translating Evidence to Practice: Two Stories from the Field. Journal of Clinical Psychology in Medical Settings. 2009;16(1):47–57. doi: 10.1007/s10880-009-9150-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Korsen N, Pietruszewski P. Translating evidence to practice: two stories from the field. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2009 Mar;16(1):47–57. doi: 10.1007/s10880-009-9150-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.AIMS Cener [Oct 30, 2011];MHIP for Behavioral Helath (Mental Health Integration Program) 2011 http://integratedcare-nw.org/.

- 121.United States Department of Defenses’ Deployment Health Clinical Center (DHCC) [Oct 30, 2011];RESPECT-Mil. http://www.pdhealth.mil/respect-mil/index.asp.

- 122.Health Services Research and Development Service Collaborative Care for Depression in the Primary Care Setting. 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 123.Kathol RG, Butler M, McAlpine DD, Kane RL. Barriers to Physical and Mental Condition Integrated Service Delivery. Psychosom Med. 2010 May 24;72(6):511–518. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181e2c4a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Unützer J, Choi Y, Cook IA, Oishi S. A web-based data management system to improve care for depression in a multicenter clinical trial. Psychiatric Services. 2002 Jun;53(6):671–673, 678. doi: 10.1176/ps.53.6.671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]