Abstract

Injury to the permanent central incisors due to trauma in the maxillofacial region, though common, may result in an uncommon sequel. We report a case of traumatic injury in a 5-year-old child with displacement of the tooth bud into the nasal floor. The identification of ectopic tooth buds poses little diagnostic challenge due to the available imaging facilities, however, in the present case the ectopic bud remained unnoticed and resulted in ectopic eruption of the tooth in the nasal cavity 1 year later. This report highlights a rare case of nasal eruption of a permanent tooth and places stress on the need for close attention to detail during maxillofacial trauma for early detection and proper management.

Background

Eruption of a tooth into the nasal cavity is a rare phenomenon, the exact aetiology of which remains obscure. A few theories have been proposed to explain it, including the theory of developmental origin, which states that ectopic eruption may occur either due to reversion to the dentition of extinct primates having three pairs of incisor teeth, defect in migration of neural crest derivatives destined to reach the jaw bones or due to a flaw in the multistep epithelial–mesenchymal interaction.1–3 Other causes include developmental disturbances such as cleft lip and palate, trauma or cystic lesions leading to tooth displacement, genetic factors, persistent deciduous teeth and supernumerary teeth.4 We report a rare case of traumatic displacement of a tooth bud with simultaneous inversion, which later resulted in eruption into the nasal cavity via a normal pattern of mucosal penetration. We also emphasise the need for close observation during maxillofacial trauma for proper diagnosis and management.

Case presentation

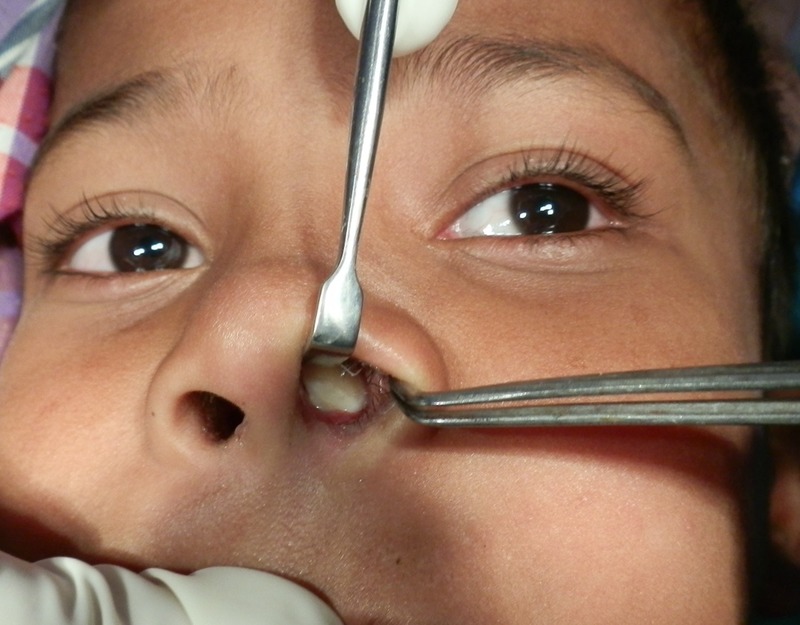

A 6-year-old male child presented to our outpatient department with pus discharge from the left nasal cavity for the past 1 month. There was a history of trauma in the maxillofacial region around 1 year earlier, which was treated by the attending surgeon; details of the treatment procedure were not available. Over the last few weeks the patient had started experiencing stuffiness in the left side of the nose and pus discharge from the same site for which he reported to us. Extraoral examination did not show any signs of swelling or tenderness around the nose and maxillary sinus. Intranasal examination revealed a pale cream coloured hard mass projecting from the left nasal floor along with purulent discharge (figure 1). The right nostril was clear. Intraoral examination revealed a mixed type of dentition. A provisional diagnosis of calcified mass into nasal cavity was performed.

Figure 1.

Bony mass in the nasal cavity, preoperatively.

Investigations

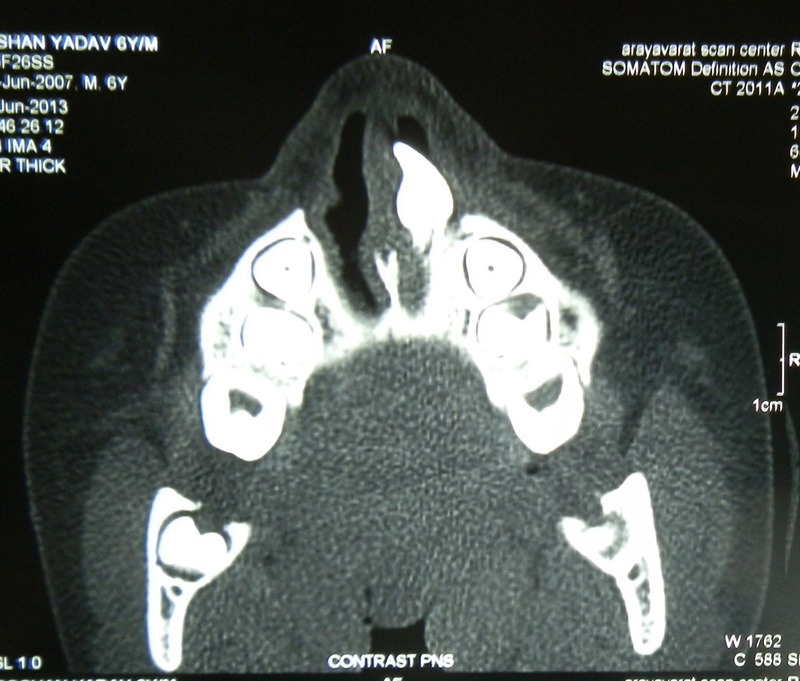

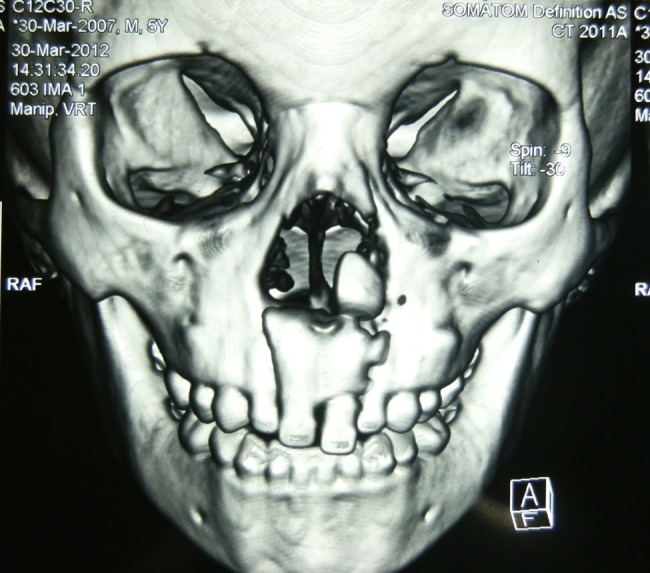

A CT scan was advised, which revealed a radio-opaque mass resembling the crown of a tooth located in the left nasal cavity between the inferior turbinate and nasal septum (figure 2). Later, the patient brought a CT scan report taken at the time of trauma (1 year earlier), which showed a fracture of the maxillary anterior alveolar bone with displacement of the left maxillary permanent tooth bud onto the nasal floor (figure 3). It was suspected that no management in relation to the displaced tooth bud was done at that time, as it was probably enclosed beneath the nasal mucosa and remained unnoticed.

Figure 2.

Contrast paranasal sinus showing the ectopic tooth in the nasal cavity.

Figure 3.

Frontal three-dimensional reconstruction at the time of injury (1 year before presenting for treatment).

As the present CT scan revealed, the ectopic tooth had an incomplete root formation. Reimplantation of the tooth bud to its original position was not considered feasible and extraction was advised.

Differential diagnosis

Differential diagnosis of the calcified mass included rhinolith, foreign body, ectopic tooth in nasal cavity and a calcifying benign or malignant tumour.

Treatment

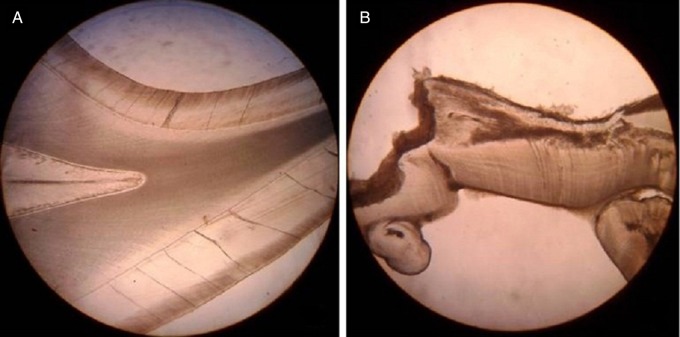

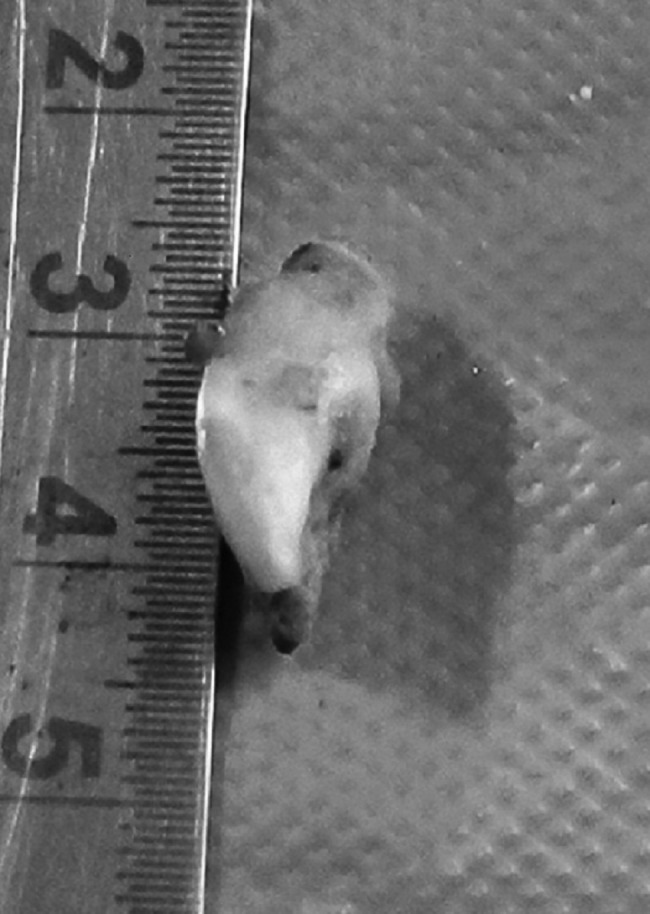

Transnasal extraction of the ectopic tooth was performed under general anaesthesia under direct vision. The gross specimen resembled a permanent central incisor tooth crown with a rudimentary (3 mm) root and was sent for histopathological examination (figure 4). The prepared ground section of the hard tissue specimen showed the presence of normal dental tissues and some disorganised dentine coronal to the pulpal space. The root was rudimentary with open apex, small pulp space and cemental tissue on its periphery (figure 5).

Figure 4.

Postoperative specimen of the extracted ectopic tooth, showing short-root formation.

Figure 5.

(A) and (B) Photomicrographs of ground section of the extracted ectopic tooth, showing presence of enamel, dentin and cementum.

Outcome and follow-up

At postoperative follow-up 10 months later the patient was asymptomatic.

Discussion

Ectopic eruption of a tooth in the nasal cavity, though rare, has been reported in the literature as early as 1897 by Smith et al5 Approximately 78 cases of intranasal teeth have been reported in the literature according to a study by Chen and Lee in 2005.6

Ectopic teeth may be found anywhere in the maxillofacial region and elsewhere in the body; the palate and maxillary sinus are the most common sites due to their anatomic proximity to the alveolus. Other relatively rare sites are the nasal cavity, orbit, mandibular condyle, coronoid process, facial skin, ethmoid sinus and teratomas in ovary, testes, anterior mediastinum and presacral region.4 An increased prevalence of ectopic tooth eruption has been found to be associated with various syndromes such as cleidocranial dysplasia, Gardner syndrome, orofacial-digital syndrome and cases of cleft lip and palate.7 8

In the present case, trauma to the maxillofacial region at the age of 5 years appeared to result in the displacement of a tooth bud. It appears that due to the impact of trauma the axis of the tooth got inverted, resulting in the crown facing towards the nasal floor. The tooth bud was probably concealed within the nasal mucosa and, though visible clearly in CT, remained unnoticed and was not treated at that time. In due course the tooth erupted, piercing the nasal epithelial lining in the same manner as eruption into the oral cavity, except that due to the confined space the crown, though fully developed, was horizontally positioned. The root was of extremely short (3 mm) length, appearing rudimentary. The root formation may have been abnormal due to alteration in the structure of the basal bone, as it is known that root formation occurs at the expense of basal bone.9 Or the unnatural root morphology may have resulted due to the impact of trauma or confinement of the bud resulting in lack of proper growth space.

The aetiology, though hypothesised, is still not clear but two different groups of causes have been proposed by Yamamoto and Kunimatsu10 in a study regarding intranasal teeth. The first being a problem in the tooth germ's development and the second in the tooth germ's migration. In our case, migration of the tooth germ due to trauma seems to be the most likely cause.

Diagnosis of intranasal an tooth is not difficult, but it is easily missed due to lack of clinical symptoms and obscure clinical presentation. Patients are usually asymptomatic but may present with variable symptoms, as discussed by Murty et al,11 which include nasal obstruction, nasal discharge (as seen in our case), facial pain, external deformities, recurrent epistaxis, foul smell in the nose and mouth, rhinorrhoea, nasal septal abscess and osteomyelitis of maxilla. Nasolacrimal duct obstruction secondary to an ectopic nasal (inferior meatus) has been reported by Alexandrakis et al.12 Radiological investigation helps in identifying the exact location of the tooth and is also useful for proper management.

There are many schools of thought pertaining to management of such cases. It is suggested that regular radiographic and clinical follow-up alone are adequate for asymptomatic patients and extraction is advised on the completion of root formation of the permanent teeth, thereby minimising the risk of developmental injury to the dentition.13 Transnasal and transpalatal approaches are the most common surgical approaches indicated. The completely formed tooth, after extraction, can be reimplanted to its original position for normal functioning. The limitations during management include inability to reimplant the tooth due to the abnormal morphology of the tooth, as was seen in the present case, and thus immediate extraction was planned.

Through this paper we have discussed a very rare case of nasal eruption of a permanent central incisor tooth following trauma to the maxillofacial region. This presentation stresses on the need for close observation, especially in cases of patients with mixed dentition, along with proper utilisation of imaging techniques for diagnostic confirmation and appropriate management.

Learning points.

The palate and maxillary sinus are the most common and nasal cavity a relatively rare site of ectopic eruption of teeth due to their anatomic proximity.

Though nasal discharge and obstruction are the most common clinical findings in patients with a nasal tooth, diagnostic confirmation requires proper interpretation of imaging techniques.

Reimplantation of the ectopic tooth is the treatment of choice in such cases, but may not be possible due to abnormal morphology of the displaced tooth.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the help of Dr Jyoti Sheoran in the final editing.

Footnotes

Contributors: MA was involved in the conception and design of study; TSK was involved in the clinical workout and drafting of case report; TG was involved in the drafting of the article and editing; SK was involved in the histopathological analysis.

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Thawley SE, Ferriere KA. Supernumerary nasal tooth. Laryngoscope 1977;87:1770–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ray B, Singh LK, Das CJ, et al. Ectopic supernumerary tooth on the inferior nasal concha. Clin Anat 2006;19:68–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smith RA, Gordon NC, De Luchi SF. Intranasal teeth. Report of two cases and review of the literature. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1979;47:120–2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gupta YK, Shah N. Intranasal tooth as a complication of cleft lip and alveolus in a four year old child: case report and literature review . Int J Paediatr Dent 2001;11:221–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim DH, Kim JM, Chae SW, et al. Endoscopic removal of an intranasal ectopic tooth. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 2003;67:79–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen HC, Lee JC. Intranasal tooth. J Med Sci 2005;25:255–8 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen A, Huang JK, Cheng SJ, et al. Nasal teeth: report of three cases. A JNR Am J Neuroradiol 2002;23:671–3 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Virk PKS, Sharma U, Kaur D. Tubercular intranasal mesiodens in oro-facial-digital syndrome. Pakistan Oral Dent J 2012;32:260–3 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marks SC, Jr, Schroeder HE. Tooth eruption: theories and facts. Anat Rec 1996;245:374–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yamamoto A, Kunimatsu Y. Intranasal tooth in Japanese Macaque. Mammal Study 2006;31:41–5 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Murty PS, Hazarika P, Hebbar GK. Supernumerary nasal teeth. Ear Nose Throat J 1988;67:128–9 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alexandrakis G, Hubbell RN, Aitken PA. Nasolacrimal duct obstruction secondary to ectopic teeth. Ophthalmol 2000;107:189–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lin IH, Hwang CF, Su CY, et al. Intranasal tooth: report of three cases. Chang Gung Med J 2004;27:385–9 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]