Abstract

We report a case of rectal atresia treated using magnets to create a rectal anastomosis. This minimally invasive technique is straightforward and effective for the treatment of rectal atresia in children.

Background

Rectal atresia is a rare congenital malformation that accounts for 1% of all anorectal malformations.1 2 These children typically have a short stenosis or fibrous band in the distal rectum without other anorectal abnormalities and the anal opening is located within the center of a normal sphincter complex. We propose the use of magnetic compression as a minimally invasive technique to treat rectal atresia.

Case presentation

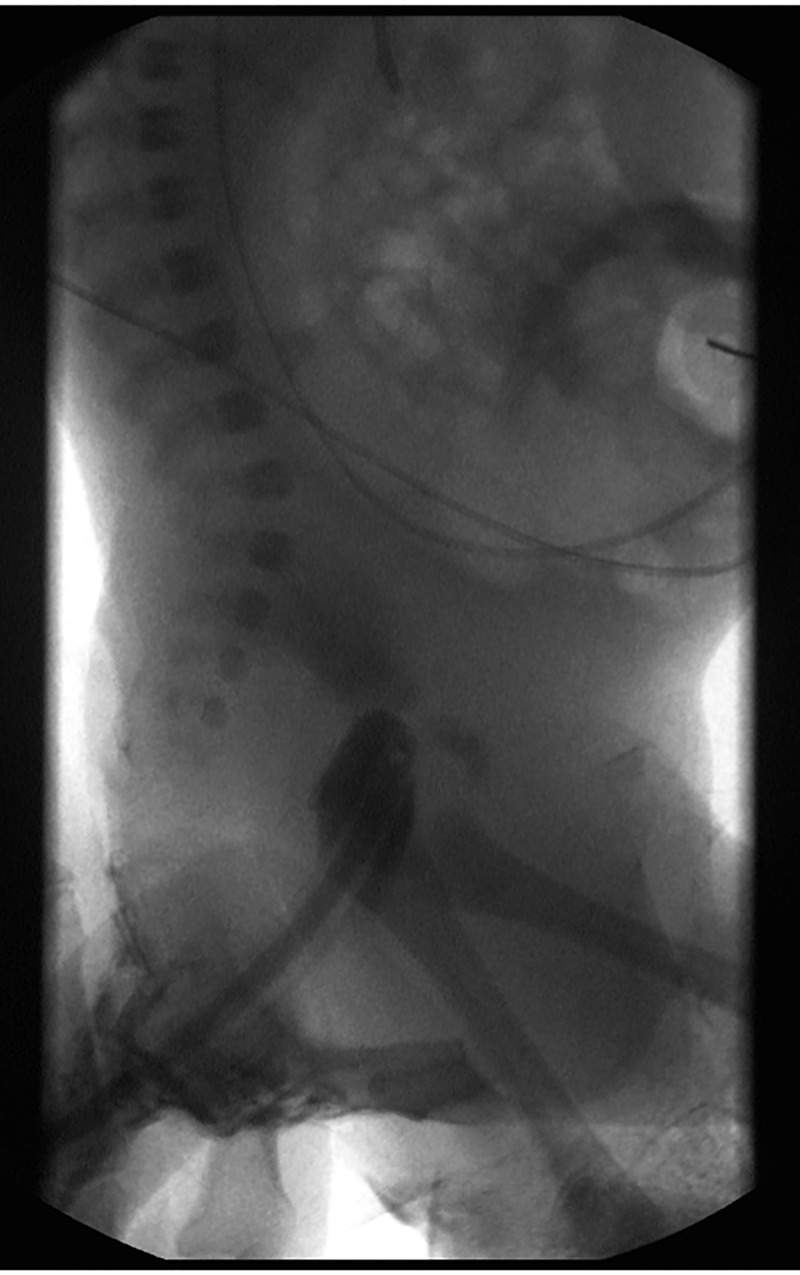

A 1680 g twin males, born at 30 weeks of gestation secondary to fetal distress was transferred to our tertiary referral centre with concern for bowel obstruction. Clinical examination revealed a normal appearing anus and external genitalia but there was failure to pass meconium. On digital rectal examination there was a blind ending rectum 2 cm above the dentate line. A plain abdominal X-ray revealed dilated loops of bowel, and a contrast enema demonstrated rectal atresia (figure 1). The child had no associated cardiac, spinal or urinary malformations.

Figure 1.

Preoperative contrast enema showing rectal atresia.

Treatment

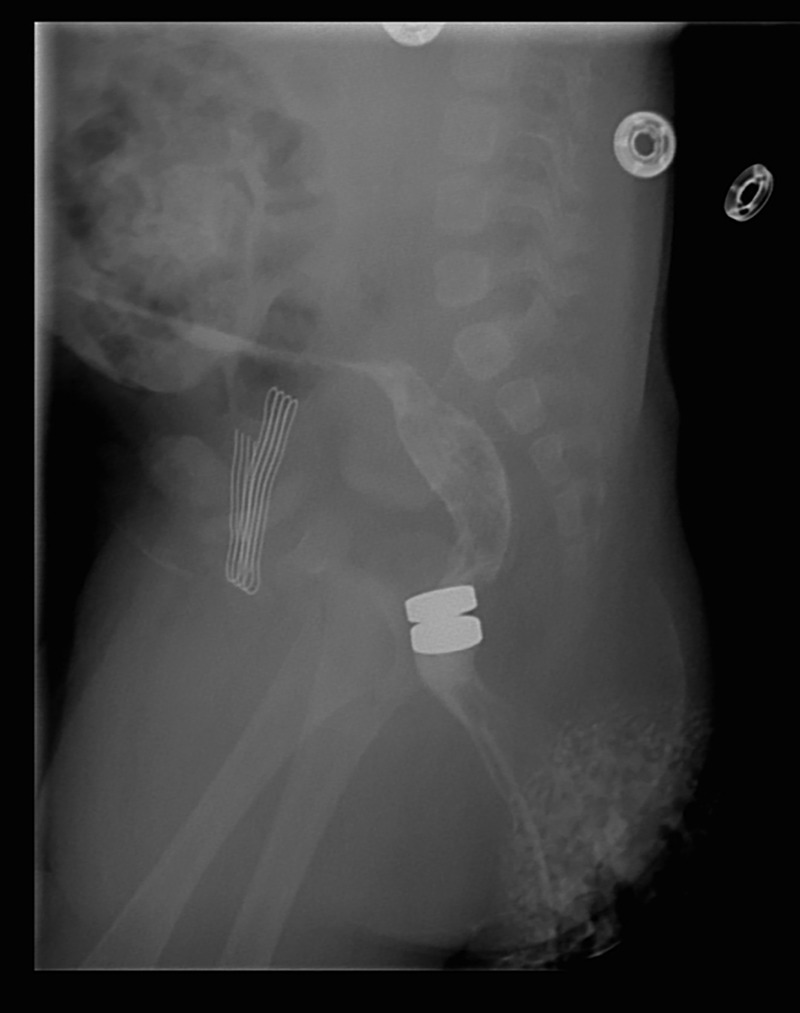

On his first day of life, the infant was treated with a diverting end colostomy and mucous fistula. At 4 months of age, fluoroscopy was used to deliver an 8 mm magnet through the mucous fistula and a second magnet through the anus to create a magnamosis between the distal and proximal pouches (figure 2). As an outpatient, he had minor discomfort and fever lasting 2 days. On the fourth day he passed the two magnets per rectum with a disc of tissue between them (figure 3).

Figure 2.

Opposed magnets following passage of one magnet through the mucous fistula and one per rectum.

Figure 3.

Extruded magnets with disc of tissue.

Outcome and follow-up

Three weeks later following passage of the magnets, a contrast enema demonstrated an intact anastomosis without stricture (figure 4). The parents performed daily rectal dilations to prevent anastomotic stenosis. At 7 months of age, the colostomy and mucous fistula were closed, restoring gastrointestinal continuity, without complication. The child is now 4 years old with normal bowel function.

Figure 4.

Post-treatment contrast enema demonstrating the absence of stricture.

Discussion

Magnamosis has been shown to be a safe and effective method of preforming gastroenteric and vascular anastomoses in animal models,3–5 and has been used successfully in humans for the treatment of bile duct strictures,6 7 and to create a biliary-enteric anastomosis.8 Magnamosis has also been suggested as a technique for creating an oesophageal anastomosis in children born with oesophageal atresia.9 There may be additional applications for magnamosis that have not yet been realised.

Multiple reports have described intestinal fistulas resulting from accidental magnet ingestion.10 This observation led to the idea that rectal atresia could be treated with an anastomosis formed by rare earth magnets (magnamosis). Rectal atresia is a rare defect that typically requires staged operative management. Several operative techniques including various pull-through procedures, transanal rectorectal anastomosis,11 posterior sagittal repair1 2 12 and endoscopic techniques13 have been described for management of this condition, but there is no clear consensus on best management.

Depending on the experience of the surgeon, this defect may be definitively repaired in the newborn. However, the conservative approach is to create an end colostomy and mucous fistula and perform the definitive repair at several months of age after optimal preoperative imaging has been obtained. By using magnet therapy, any disruption to the sphincter mechanism and associated nerves may be avoided. Magnamosis offers a minimally invasive technique as an option for repair of this congenital anomaly. In anorectal malformations with favourable anatomy, this procedure may avoid an operative repair such as posterior sagittal reconstruction.

We propose that magnamosis can be considered as an alternative option for the treatment of rectal atresia in certain children. Anastomotic stricture is a primary concern when using this technique and we recommend scheduled anastomotic dilations per rectum similar to those performed in children with other anorectal malformations repaired using the traditional posterior sagittal anorectoplasty.

Patient's perspective

“We were so lucky that we had the best care! The technique sounded really interesting to say the least, but non-invasive and we agreed to do anything that is best for our son. We hope other kids can benefit from this procedure. Our son is 4 years old now and very healthy and happy.” Patient's mother

Learning points.

Rectal atresia is a rare congenital anomaly that frequently requires staged operative repair.

Children born with rectal atresia have a normal anal canal and anal sphincter mechanism.

We propose that magnamosis can be considered as a less invasive treatment for rectal atresia in infants.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the patient and his family for their willingness to be creative with treatment options and for their support in publishing this report.

Footnotes

Contributors: KWR did the literature review and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. ERS, MDR and GPF were all directly involved in the patient care and made major edits and contributions to the final version of the manuscript.

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Hamrick M, Eradi B, Bischoff A, et al. Rectal atresia and stenosis: unique anorectal malformations. J Pediatr Surg 2012;47:1280–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Levitt MA, Peña A. Anorectal malformations. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2007;2:33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pichakron KO, Jelin EB, Hirose S, et al. Magnamosis II: magnetic compression anastomosis for minimally invasive gastrojejunostomy and jejunojejunostomy. J Am Coll Surg 2011;212:42–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Erdmann D, Sweis R, Heitmann C, et al. Side-to-side sutureless vascular anastomosis with magnets. J Vasc Surg 2004;40:505–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jamshidi R, Stephenson JT, Clay JG, et al. Magnamosis: magnetic compression anastomosis with comparison to suture and staple techniques. J Pediatr Surg 2009;44:222–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oya H, Sato Y, Yamanouchi E, et al. Magnetic compression anastomosis for bile duct stenosis after donor left hepatectomy: a case report. Transplant Proc 2012;44:806–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jang SI, Kim J-H, Won JY, et al. Magnetic compression anastomosis is useful in biliary anastomotic strictures after living donor liver transplantation. Gastrointest Endosc 2011;74:1040–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Avaliani M, Chigogidze N, Nechipai A, et al. Magnetic compression biliary-enteric anastomosis for palliation of obstructive jaundice: initial clinical results. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2009;20:614–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zaritzky M, Ben R, Zylberg GI, et al. Magnetic compression anastomosis as a nonsurgical treatment for esophageal atresia. Pediatr Radiol 2009;39:945–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Naji H, Isacson D, Svensson JF, et al. Bowel injuries caused by ingestion of multiple magnets in children: a growing hazard. Pediatr Surg Int 2012;28:367–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Upadhyaya P. Rectal atresia: transanal, end-to-end, rectorectal anastomosis: a simplified, rational approach to management. J Pediatr Surg 1990;25:535–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Osman MA. Rectal atresia: multiple approaches in neonates. Med J Cairo Univ 2012;80:157–62 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stenström P, Clementson Kockum C, Arnbjörnsson E. Rectal atresia—operative management with endoscopy and rransanal approach: a case report. Minim Invasive Surg 2011;2011:1–5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]