Abstract

Wild grown European blackberry Rubus fruticosus) plants are widespread in different parts of northern countries and have been extensively used in herbal medicine. The result show that European blackberry plants are used for herbal medicinal purpose such as antimicrobial, anticancer, antidysentery, antidiabetic, antidiarrheal, and also good antioxidant. Blackberry plant (R. fruticosus) contains tannins, gallic acid, villosin, and iron; fruit contains vitamin C, niacin (nicotinic acid), pectin, sugars, and anthocyanins and also contains of berries albumin, citric acid, malic acid, and pectin. Some selected physicochemical characteristics such as berry weight, protein, pH, total acidity, soluble solid, reducing sugar, vitamin C, total antioxidant capacity, antimicrobial screening of fruit, leaves, root, and stem of R. fruticosus, and total anthocyanins of four preselected wild grown European blackberry (R. fruticosus) fruits are investigated. Significant differences on most of the chemical content detect among the medicinal use. The highest protein content (2%), the genotypes with the antioxidant activity of standard butylated hydroxyanisole (BHA) studies 85.07%. Different cultivars grown in same location consistently show differences in antioxidant capacity.

Keywords: Anticancer, antidiabetic, antidysentery, antimicrobial, antioxidant, blackberry, phototherapeutics, R. fruticosus, rosaceae

INTRODUCTION

In British folk medicine, the bramble has a reputation for curing and preventing a wide variety of ailments.[1] The species of blackberry (Rubus fruticosus) most common in Britain is naturalized throughout most of the world, including north America. In folk medicinal records, it is often not possible to trace the actual species used in the past. Blackberry root is one component of a decoction used to treat dysentery.[2] Blackberry root has been used to treat diarrhea.[3] Blackberry bush has been used to treat whooping cough.[4] Blackberry juice has been recommended for colitis.[5] Whereas a tea made from the roots has been used for labor pain.[6] The leaves of the blackberry have been chewed for toothache.[7] The berry is a powerful source of antioxidant.[8] R. fruticosus (European blackberry, European bramble, known as vilaayati anchhu) is cultivated in the valley of Kashmir, Assam, and Tamilnadu (India) up to 2000 meter. The plant gave triterpenic acid and rubitic acid characterized as 7 alpha-hydroxyursolic acid.[9] Blackberries are notable for their high nutritional contents of dietary fiber, vitamin C, vitamin K, and the essential mineral manganese.[10] The root contains saponins and tannins, whereas leaf contains fruits acid, flavonoids, and tannins.[11] Fruits are gathered (as of most other blackberries) in the wild for jam, syrups, wine, and liqueur. Because there are many similar species, it seems doubtful, whether the reports refer really to this species.[12] Blackberry is a perennial shrub. It has sprawling, woody, and thorny stems. They can reach the height of about 5 meters. It has dark green hairy leaves, toothed along the margins. Leaves grow in clusters of three to five. Flowers are white to pale pink, appearing from late summer until autumn. Fruits are the well-known fleshy black berries.[13]

Description

In its first year, a new stem, the primocane, grows vigorously to its full length of 3-6 m (in some cases, up to 9 m), arching or trailing along the ground and bearing large palmately compound leaves with five or seven leaflets; it does not produce any flowers. In its second year, the cane becomes a floricane and the stem does not grow longer, but the lateral buds break to produce flowering laterals (which have smaller leaves with three or five leaflets).[14] First and second year shoots usually have numerous short-curved very sharp prickles that are often erroneously called thorns. These prickles can tear through denim with ease and make the plant very difficult to navigate around. Unmanaged mature plants form a tangle of dense arching stems, the branches rooting from the node tip on many species when they reach the ground. Vigorous and growing rapidly in woods, scrub, hillsides, and hedgerows, blackberry shrubs tolerate poor soils, readily colonizing wasteland, ditches, and vacant lots.[15,16] The flowers are produced in late spring and early summer on short racemes on the tips of the flowering laterals. Each flower is about 2-3 cm in diameter with five white or pale pink petals. The newly developed primocane fruiting blackberries flower and fruit on the new growth.[17]

Stem

Canes arched or trailing up to 7-meter long, green, purplish or red, smooth or moderately hairy, round or angled, with numerous curved or straight prickles of different sizes.

Leaves

Compound with three or five oval leaflets. Leaflets are usually dark-green above and lighter green beneath, with small teeth around the edges.[18]

Flowers

White or pink, 2-3 cm in diameter, formed in clusters at the ends of short branches; petals five.

Fruit

A berry changing color from green to red to black as it ripens, 1-3 cm in diameter, consisting of an aggregate of fleshy segments or drupelets, each containing one seed.

Seed

Light to dark brown, somewhat triangular, 2-3-mm long, deeply and irregularly pitted.

Root

Most roots occur in the top 20 cm of soil but a few are up to 1-m deep; there is a well-defined crown at ground level.[19]

Taxonomy

Botanical name: R. fruticosus L. aggregate-Family Rosaceae (rose family) [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Plant of R. fruticosus

Blackberry comprises a number of closely related plants that for convenience are dealt with (aggregated) under the one Latin name. On a world scale, R. fruticosus includes approximately 2000 named species, subspecies, and varieties and belongs to the family of the Rosaceae (Rose Family), which is collectively referred to as taxa. The identities and correct names of the taxa occurring in Australia require clarification.

Standard common name

Blackberry, also known as European blackberry.

Relationship to other species in Australia

The term “European blackberry” is used to distinguish it from closely related north American Rubus species, which occasionally escape from cultivation in Australia. There are native species of Rubus (some known as brambles) in Australia. Care should be taken not to confuse blackberry with the indigenous Rubus species or commercial varieties of raspberries, blackberries, and brambleberries.[20]

Economic impact

Net annual cost to Australia using early 1980s data for Victoria (Vic.), New South Wales (NSW), Tasmania (Tas), and Western Australia (WA) was $41.5 million based on estimated losses from primary production and costs of control and not including non-market costs or any estimate of the impact on natural ecosystems. It is estimated that $0.3 million would need to be spent to obtain a reasonably accurate estimate of current costs.[21]

Chemical characterization

Total phenolic quantification

Determination of total phenolic compounds is performed by the Folin-Ciocalteau method, adapted to a microplate reader. Gallic acid is use as the standard, and the results are expressed as milligram of gallic acid equivalents (mg GAE).

Peroxyl radical-scavenging capacity determination

Peroxyl radical-scavenging capacity is determined by the oxygen radical absorbance capacity method, as described by Tavares et al., (2010b). The final results are calculated using the differences in area under the fluorescence decay curves between the blank and the sample and are expressed as lM trolox equivalents.

Phenolic profile determination by liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS)

Extracts and digested fractions are applied to a C-18 column and analyzed by a LCQ-Deca system controlled by the XCALIBUR software (2.0, Thermo Finnigan), as reported by Tavares et al., (2010b). The LCQ-Deca system comprised a surveyor autosampler, pump and photo diode array (PDA) detector and a Thermo Finnigan mass spectrometer ion trap.[22,23] Blackberry fruits are well known to be a rich source of polyphenols and to exhibit high antioxidant capacity.[24,25]

PHYTOCONSTITUENTS

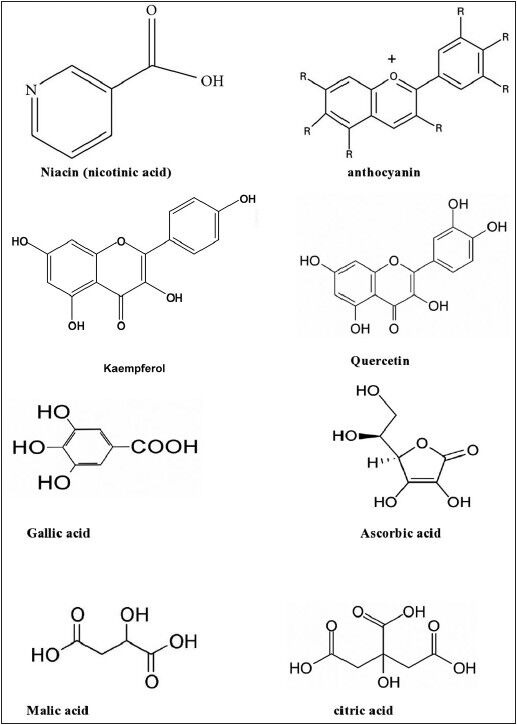

The plant materials contain various type of phytochemical constituents such as alkaloids, flavonoids, tannins, saponins, glycosides, terpenoids, sterols, and carbohydrates.[26,27,28] It also contains ascorbic acid, organic acids, tannins, and volatile oils.[29] On the basis of these chemical constituents, the plant is very useful antidiarrheal and soothes inflamed mucosa. Decoction of leaves is use as tonic and gargle. Poultice of the leaves is applied to abscesses and skin ulcers.[30,31] Blackberries contain numerous phytochemical including polyphenols, flavonoids, anthocyanins, salicylic acid, ellagic acid, and fiber.[32,33] Blackberries have both soluble and insoluble fiber.[34] [Figure 2].

Figure 2.

Phytoconstituents of R. fruticosus

MEDICAL USES

Blackberries are known for their anticancer properties. As they contain antioxidants, they are known to destroy the free radicals that harm cells and can lead to cancer. They also help protect and strengthen the immunity, which lowers the risk of cancer. They are especially helpful when it comes to reducing the risk of esophageal, cervical, and breast cancer.[35] Blackberry leaves have been traditionally used in herbal medicine as an antimicrobial agent and for their healthful antioxidant properties. A laboratory study was published in the “International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents” in July 2009.[36] Young blackberry leaves have high levels of antioxidants, or oxygen radical absorbance capacity, according to a study conducted by the U. S. Department of Agriculture's Agricultural Research Service and published in the “Journal of Agricultural Food Chemistry” in February 2000.[37] R. fruticosus has been used in Europe to treat diabetes. An extract of the leaves showed a hypoglycemic effect on diabetic rats.[38] Blackberry leaves and roots are a long-standing home remedy for anemia, regulates menses, diarrhea, and dysentery. The fruit and juice are taken for anemia. A standard infusion made, which can also be applied externally as a lotion, reported to cure psoriasis and scaly conditions of the skin. Blackberries are also used to make wine, brandy, and flavor liqueurs and cordials.[39] They are used to treat sore throats, mouth ulcers, and gum inflammations. A decoction of the leaves is useful as a gargle in treating thrush and also makes a good general mouthwash.[40]

TRADITIONAL USES

Because the plant is strongly astringent, infusions are used to relieve diarrhea. As a mouthwash, it is used to strengthen spongy gums and ease mouth ulcers. The berries make a pleasant gargle for swallowing. Poultices or compresses are used externally on wounds and bruises. Decoctions are used to relieve diarrhea and hemorrhoids. The tannins in the herb not only tighten tissue but also help to control minor bleeding.[41]

CONCLUSION

Plants of R. fruticosus are widespread in northern countries of the world. It has a lot of medicine use. Various blackberry plants are useful in the treatment of cancer, dysentery, diarrhea, whopping cough, colitis, toothache, anemia, psoriasis, sore throat, mouth ulcer, mouthwash, hemorrhoids, and minor bleeding. R. fruticosus has different pharmacological activities like anticancer, antimicrobial, antioxidant, antidysentery, antidiabetic, and antidiarrheal. This review article has reestablished various properties of “Rubus fruticosus” and pharmacological activities of plant with various phytochemical constituents such as alkaloids, flavonoids, tannins, saponins, glycosides, terpenoids, sterols, and carbohydrates. It also contains ascorbic acid, organic acids, tannins, and volatile oils.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared

REFERENCES

- 1.Hatfield G. California: ABC-CLIO; 2004. Encyclopedia of folk medicine. Encyclopedia of Folk Medicine: Old World and New World Traditions, illustrated; p. 33. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Meyer C. 19th ed. Glenwood: Meyer Books; 1985. American Folk Medicine; p. 178. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cadwallader DE, Wilson FJ. Vol. 49. Collections of the Georgia historical society; 1965. Folklore medicine among Georgia's piedmont Negroes after the Civil War; pp. 217–27. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hohman GJ. The long hidden friend. J Am Folklore. 1904;17:89–152. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Browne RB. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California publications; 1958. Popular beliefs and practices from Alabama. Folklore studies 9; p. 52. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Parler MC. Vol. 15. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas; 1962-3. University student contributors. Folk beliefs from Arkansas; p. 51. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hatfield G. Woodbridge: Boydell; 1994. Country remedies: Traditional East Anglian plant remedies in the twentieth century; p. 55. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wynn SG, Fougere BJ, editors. 1st ed. Maryland Heights, Missouri: Mosby; 2006. Veterinary herbal medicine. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Verlag H. Indian medicinal plants; an illustrated dictionary. In: Khare CP, editor. Encyclopedia of Indian Medicinal Chemistry. Vol. 2. New York City: Springer Publisher; 2004. p. 560. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Condé Nast, Nutrition Facts and analysis for blackberries, raw, Inc; c2013. [Last accessed on 2013 Jul 10]. Nutritiondata.self.com [Internet] Available from: http://nutritiondata.self.com/facts/fruits-and-fruit-juices/1848/2 . [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pullaiah T. Vol. 1. New Delhi: Daya Publishing House a unit of Astral International (P) Ltd; 2006. Encyclopedia of world medicine plant; p. 1697. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weber; 1985. Ehlers 1960. P. 278, Hegi IV (2A), 1955, Mansfeld 1959; p. 659. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Health from nature. [Last accessed on 2013 Jul 15]. http://health-from-nature.net[Internet] Available from: http://health-from-nature.net/Blackberry.html .

- 14.Krewer G, Fonseca M, Brannen P, Horton D. Home Garden: Raspberries, Blackberries Cooperative Extension Service/The University of Georgia College of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huxley A, editor. Macmillan; 1992. New RHS Dictionary of Gardening. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Blamey M, Grey-Wilson C. Flora of Britain and Northern Europe. 1989 [Google Scholar]

- 17.mcshanesnursery.com [Internet]. McShane's Nursery and Landscape Supply. [Last accessed on 2013 Aug 25]. Available from: http://www.mcshanesnursery.com/wpcontent/uploads/2010/06/BLACKBERRIES1.pdf .

- 18.Clarence Valley Council, Inc; 2014. [Last accessed on 2013 Aug 26]. clarence.nsw.gov.au [Internet] Available from: http://www.clarence.nsw.gov.au/content/uploads/Blackberry.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 19.Parsons WT. Noxious Weeds of Australia. 2nd ed. Collingwood: CSIRO Publishing; 2001. Noxious weed legislation in Australia-Family Rosaceae; p. 578. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bruzzese E, Mahr F, Faithfull I. PO Box48, Frankston, Victoria, Australia 3199: Keith Turnbull Research Institute and Weeds CRC. Publication date: September 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Economics of blackberries: Current data and rapid evaluation techniques. In: James R, Lockwood M, editors; Groves, et al., editors. Towards an integrated management system for blackberry (Rubus fruticosus L agg.) Vol. 13. Proceedings of a workshop sponsored by the CRC for Weed Management Systems, Albury Plant Protection Quarterly; 1998. pp. 175–9. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tavares L, Carrilho D, Tyagi M, Barata D, Serra AT, Duarte CM, et al. Antioxidant capacity of Macaronesian traditional medicinal plants. Molecules. 2010;15:2576–92. doi: 10.3390/molecules15042576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tavares L, Fortalezas S, Carrilho C, McDougall GJ, Stewart D, Ferreira RB, et al. Antioxidant and anti proliferative properties of strawberry tree tissues. J Berry Res. 2010b;1:3–12. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moyer RA, Hummer KE, Finn CE, Frei B, Wrolstad RE. Anthocyanins, phenolics, and antioxidant capacity in diverse small fruits: Vaccinium, Rubus, and Ribes. J Agric Food Chem. 2002;50:519–25.24. doi: 10.1021/jf011062r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Siriwoharn T, Wrolstad RE, Finn CE, Pereira CB. Influence of cultivar, maturity, and sampling on blackberry (Rubus L. hybrids) anthocyanins, polyphenolics, and antioxidant properties. J Agric Food Chem. 2004;52:8021–30. doi: 10.1021/jf048619y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Aduragbenro DA, Yeside OO, Adeolu AA, Olanrewaju MJ, Ayotunde SA, Olumayokun AO, et al. Blood pressure lowering effect of Adenanthera pavonina Seed extract on normotensive rats. Rec Nat Prod. 2009;3:282–9. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Harborne JB. London: Chapman and Hall; 1973. Phytochemical methods; p. 117. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kokate CK, Purohit AP, Gokhale SB. 4th ed. New Delhi: Vallabh Prakashan; 1997. Practical Pharmacognosy; pp. 106–11. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wada L, Ou B. Antioxidant activity and phenolic content of Oregon caneberries. J Agr Food Chem. 2002;50(Suppl 12):3495–500. doi: 10.1021/jf011405l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sher H. Ethnoecological evaluation of some medicinal and aromatic plants of Kot Malakand Agency. Pak Sci Res Essays. 2011;6(Suppl 10):2164–73. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Riaz M, Ahmad M, Rahman N. Antimicrobial screening of fruit, leaves, root and stem of Rubus fruticosus. J Med Plant Res. 2011;5(Suppl 24):5920–4. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sellappan S, Akoh CC, Krewer G. Phenolic compounds and antioxidant capacity of Georgia-grown blueberries and blackberries. J Agric Food Chem. 2002;50:2432–8. doi: 10.1021/jf011097r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Conde Nast; 2012. “Nutrition facts for raw blackberries”. [Internet] Nutritiondata.com. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jakobsdottir G, Blanco N, Xu J, Ahrné S, Molin G, Sterner O, et al. Formation of short-chain fatty acids, excretion of anthocyanins, and microbial diversity in rats fed blackcurrants, blackberries, and raspberries. J Nutr Metab 2013. 2013 doi: 10.1155/2013/202534. 202534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Live and Feel, Inc; c2014. [Last accessed on 2013 Aug 28]. liveandfeel.com [Internet] Available from: http://www.liveandfeel.com/vegetables/blackberry.htm . [Google Scholar]

- 36.Martini S, Addario CD, Colacevich A, Focardis, et al. Antimicrobial activity against Helicobacter pylori strains and antioxidant properties of blackberry leaves (Rubus ulmifolius) and isolated compounds. Int J Antimicrob Ag. 2009;34:50–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2009.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang SY, Lin HS. Antioxidant activity in fruits and leaves of blackberry, raspberry, and strawberry varies with cultivar and developmental stage. J Agric Food Chem. 2000;48:140–6. doi: 10.1021/jf9908345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bailey CJ, Day C. Traditional plant medicines as treatments for diabetes. Diabetes Care. 1989;12:553–64. doi: 10.2337/diacare.12.8.553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Alternatives from nature by rainbear, Inc; 1995-10. [Last accessed on 2013 Sep 04]. herbsrainbear.com [internet] Available from: http://herbsrainbear.com/encylopedia/blackberry.htm . [Google Scholar]

- 40.altnature.com [Internet]. Blackberry Herbal Use and Medicinal Properties. [Last accessed on 2013 Sep 06]. Available from: http://www.altnature.com/gallery/Blackberry.htm .

- 41.Cloverleaf Farm, Inc; c2014. [Last accessed on 2013 Sep 06]. cloverleaffarmherbs.com [Internet] Available from: http://www.cloverleaffarmherbs.com/blackberry/#sthash. 0×JqXObG.dpbs . [Google Scholar]