Summary

More frequent utilization and continuous improvement of imaging techniques has enhanced appreciation of the high phenotypic variability of autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease, improved understanding of its natural history, and facilitated the observation of its structural progression. At the same time, identification of the PKD1 and PKD2 genes has provided clues to how the disease develops when they (genetic mechanisms) and their encoded proteins (molecular mechanisms) are disrupted. Interventions designed to rectify downstream effects of these disruptions have been examined in animal models and some are currently tested in clinical trials. Efforts are underway to determine whether interventions capable to slow down, stop or reverse structural progression of the disease will also prevent decline of renal function and improve clinically significant outcomes.

Introduction

Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD) occurs worldwide and in all races. It has a disease expectancy at birth (i.e. prevalence of disease causing mutations at birth) estimated to be between 1:400 and 1:1000. It is genetically heterogeneous with two genes identified, PKD1 (chromosome 16p13.3) and PKD2 (4q21). The PKD1 and PKD2 proteins, polycystin-1 (PC1, ~460kDa) and polycystin-2 (PC2, ~110kDa) constitute a subfamily (TRPP) of transient receptor potential (TRP) channels.

Awareness of ADPKD has greatly increased in the last three decades. More frequent utilization and continuous improvement of imaging techniques has enhanced appreciation of its high phenotypic variability, improved understanding of its natural history, and facilitated the observation of its structural progression. At the same time, identification of PKD1 and PKD2 has provided clues to how the disease develops when they (genetic mechanisms) and their encoded proteins (molecular mechanisms) are disrupted. Interventions designed to rectify downstream effects of these disruptions have been examined in animal models and some are currently tested in clinical trials. Efforts are underway to determine whether interventions capable to slow down, stop or reverse structural progression of the disease will also prevent decline of renal function and improve clinically significant outcomes.

Natural history of ADPKD

The Consortium for Radiologic Imaging Study of PKD (CRISP) study, an ongoing observational study of ADPKD patients initiated in 2001, has provided invaluable information on how cysts develop and grow.(1) Participants were age 15 to 46 years old and had a measured or estimated creatinine clearance ≥70 mL/min at enrolment. Two thirds had an increased risk for renal insufficiency defined by presence of hypertension and/or low grade proteinuria. During the first phase of the study (CRISP I) two hundred forty-one ADPKD subjects had four yearly visits between January 2001 and August 2006. At each visit, total kidney volume was measured by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and glomerular filtration rate (GFR) was determined from iothalamate clearance. In most subjects, kidneys and cysts increased in volume exponentially from year to year. At baseline total kidney volume was 1060 ± 642 mL and mean increase over three years was 204 mL (5.27%) per year. Rates of kidney and cyst enlargement were strongly correlated and varied widely from subject to subject. Extrapolation of total kidney volume in individual CRISP subjects back to an age of 18 was consistent with volumes observed by direct measurement in the subset of patients who were 18 years old during the study. The good fit of extrapolated and measured values indicates that total kidney volume growth rate is a defining trait for individual patients.(2) CRISP results have been confirmed by recent a European study of 100 ADPKD patients with an eGFR ≥70 mL/min who underwent standardized MRIs with unenhanced sequences six months apart. Baseline total kidney volume was 1003±568 mL and estimated annual growth rate 5.36%(3).

Baseline and subsequent rate of increase in total kidney volume were associated with declining GFR. The correlation between kidney volume and GFR slopes was significant (r −0.186, P = 0.005). To determine if kidney enlargement was uniformly associated with decreasing renal function across renal size, the cohort was stratified into three groups of increasing baseline volume. GFR slopes were not significantly different from zero in the <750 ml and the 750 – 1500 ml subgroups. On the other hand, the slope decreased significantly in the >1500 ml subgroup (−4.3 ± 8.07 ml per minute per year, P <.001).

Renal blood flow (RBF) was measured by MRI in a subset of CRISP I participants. RBF decreased from year to year, while overall GFR remained stable. Analysis of baseline predictors of disease progression showed that RBF and urinary sodium and albumin excretions, in addition to total kidney volume, independently predicted kidney volume increase.(4) The association between urine sodium excretion and structural progression suggests that sodium intake may affect cyst growth. RBF, in addition to total kidney volume, was an independent predictor of GFR decline. These associations point to the importance of hemodynamic factors in the progression of ADPKD.

ADPKD is characterized by high phenotypic variability. While many ADPKD subjects would benefit from a therapy capable to slow down disease progression, others with mild disease would not require treatment even if one became available. The genic and allelic factors, modifier genes, gender effects, and environmental factors that determine this phenotypic variability are discussed in detail by Rossetti and Harris in this issue.

Genetic and molecular mechanisms of ADPKD as treatment targets

Evidence from animal models of ADPKD and analysis of cystic epithelia have shown that renal cysts may develop from loss of functional polycystin with somatic inactivation of the normal allele consistent with a two hit mechanism. However, dosage reduction of the protein in Pkd1 animal models with hypomorphic alleles indicates that cysts can develop even if the protein is not completely lost.(5) Development of renal cystic disease in Pkd1 and Pkd2 transgenic rodents(6–9) suggests that additional genetic mechanisms that disrupt the balance of polycystin expression may also affect their function and lead to development of PKD.

Conditional knockouts of of Pkd1 or ciliogenic genes (Tg737 and Kif3a) at various time points have shown that the timing of Pkd1 inactivation or ciliary loss determines the rate of development of cystic disease.(10–13) Kidney-specific inactivation of Kif3a in newborn mice leads to rapid cyst development, whereas inactivation at postnatal day 10 or later does not, despite comparable loss of primary cilia.(10) Cysts also develop rapidly in the pars recta and thick ascending limbs of Henle of adult mouse kidneys subjected to renal ischemic/reperfusion injury to stimulate cell proliferation when Kif3a is conditionally inactivated.(14) Age-dependence, location, and induction of the cysts by ischemia-reperfusion injury suggest that cyst formation is associated with increased rates of cell proliferation and/or transcriptional programs associated with renal development. This suggests that targeting cyst growth may be more effective than targeting cyst initiation after completion of renal development.

The polycystins are essential to maintain the differentiated phenotype of the tubular epithelium. Reduction in one of these proteins below a critical threshold results in a phenotypic switch characterized by inability to maintain planar polarity, increased rates of proliferation and apoptosis, expression of a secretory phenotype, and remodeling of the extracellular matrix. The molecular mechanisms responsible for this phenotypic switch are reviewed in detail by Gallagher, Germino and Somlo in this issue.

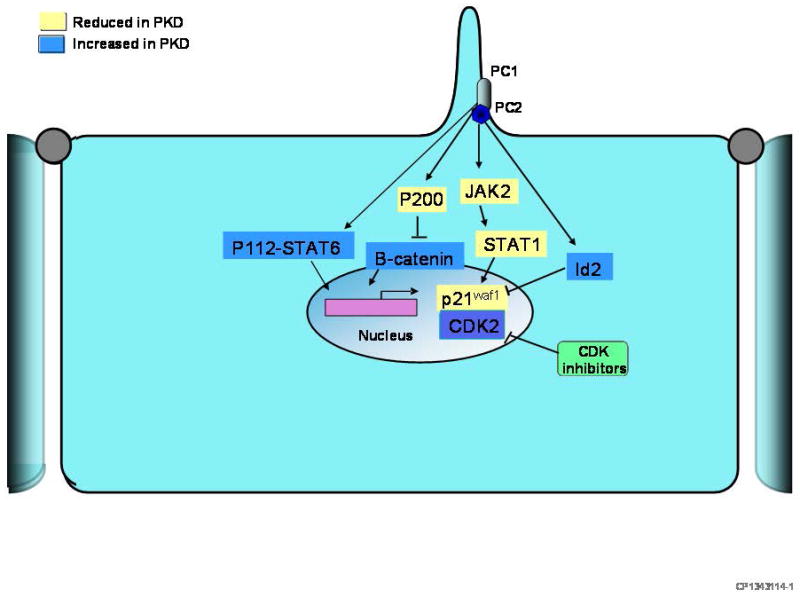

Several studies have implicated the polycystins directly in the regulation of the cell cycle (Figure 1). PC1 was reported to activate JAK2/STAT-1, upregulate p21waf (a cell cycle inhibitor), inhibit cyclin-dependent kinase 2 (Cdk2) and induce cell cycle arrest in G0/G1 in a PC2-dependent manner. PC2 was reported to bind Id2, a helix-loop-helix protein, and prevent its translocation to the nucleus and suppression of p21waf, thus preventing Cdk2 activation and cell cycle progression. Two studies have suggested that the C-terminal tail of PC1 can be cleaved and migrate to the nucleus. Two non-mutually exclusive models have been suggested. In the first, PC1 normally sequesters the transcription factor STAT6 on cilia thereby preventing its activation. Interruption of luminal fluid flow (e.g. after ureteral clamping or renal injury) triggers the cleavage of the final 112 amino acids. This p112 fragment interacts with STAT6 and the co-activator P100 and stimulates transcriptional activity.(15) In the second, mechanical stimulation of the primary cilium normally triggers the cleavage and release of the entire C terminal tail (p200). This p200 fragment contains a nuclear localization motif, binds β-catenin in the nucleus, and inhibits its ability to activate T-cell factor-dependent gene transcription, a major effector of the canonical Wnt signaling pathway.(16)

Figure 1.

Diagram depicting hypothetical mechanisms by which the polycystins directly affect gene transcription and regulate the cell cycle. PC1 binds and activates JAK2 in a PC2-dependent manner. JAK2 is a member of the Janus kinase family of tyrosine kinases which in turn phosphorylates and activates the transcription factor STAT-1, upregulating p21waf (a cell cycle inhibitor), inhibiting cyclin-dependent kinase 2 (Cdk2), and inducing cell cycle arrest in G0/G1. PC2 binds Id2, a helix-loop-helix protein, and prevents its translocation to the nucleus and suppression of p21waf, thus preventing Cdk2 activation and cell cycle progression. The C-terminal tail of PC1 can be cleaved and migrate to the nucleus. Two non-mutually exclusive models have been suggested. In the first, PC1 normally sequesters the transcription factor STAT6 on cilia thereby preventing its activation. Interruption of luminal fluid flow (e.g. after ureteral clamping or renal injury) triggers the cleavage of the final 112 amino acids. This p112 fragment interacts with STAT6 and the co-activator P100 and stimulates transcriptional activity. In the second, mechanical stimulation of the primary cilium normally triggers the cleavage and release of the entire C terminal tail (p200). This p200 fragment contains a nuclear localization motif, binds β-catenin in the nucleus, and inhibits its ability to activate T-cell factor-dependent gene transcription, a major effector of the canonical Wnt signaling pathway.

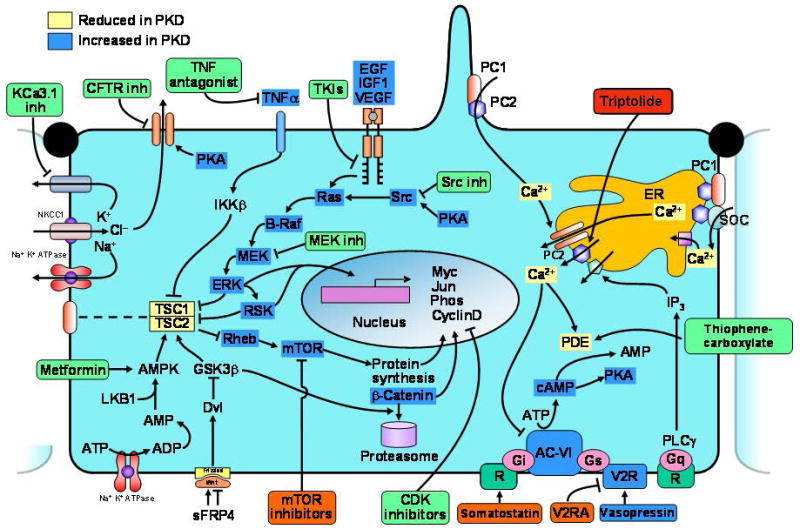

The location of the polycystins in the primary cilium has received much attention. In tubular epithelial cells the cilium projects into the lumen and is thought to have a sensory role. The PC1-PC2 complex acts as a sensor on cilia that translates mechanical or chemical stimulation into calcium influx through PC2 channels (Figure 2). This in turn induces calcium release from intracellular stores where PC2 interacts with inositol triphosphate and ryanodine receptors.(17–19) ADPKD cyst cells lack flow-sensitive calcium signaling and exhibit reduced endoplasmic reticulum calcium stores, store-depletion-operated entry and, under certain conditions, intracellular calcium concentrations.(20–23) The polycystins also play an important role in the regulation of the endoplasmic reticulum calcium stores and intracellular calcium homeostasis in vascular smooth muscle cells and cardiac myocytes, The precise mechanisms by which this regulation operates remain uncertain.(19, 24)

Figure 2.

Diagram depicting hypothetical pathways up- or down regulated in polycystic kidney disease and rationale for treatment with V2R antagonists, somatostatin, triptolide; tyrosine kinase, src, MEK, TNFα, mTOR or CDK inhibitors; metformin, and CFTR or KCa3.1 inhibitors (drugs in pre-clinical trials only in green boxes; drugs in clinical trials in orange boxes). Dysregulation of [Ca2+]i, increased concentrations of cAMP, mislocalization of ErbB receptors, and upregulation of EGF, IGF1, VEGF and TNFα occur in cells/kidneys bearing PKD mutations. Increased accumulation of cAMP in polycystic kidneys may result from: (i) disruption of the polycystin complex, since PC1 may act as a Gi protein-coupled receptor; (ii) stimulation of Ca2+ inhibitable AC6 and/or inhibition of Ca2+-dependent PDE1 by a reduction in [Ca2+]i; (iii) increased levels of circulating AVP due to an intrinsic concentrating defect; (iv) upregulation of AVP V2Rs. Increased cAMP levels contribute to cystogenesis by stimulating chloride and fluid secretion. In addition, cAMP stimulates mitogen-activated protein kinase/extracellularly regulated kinase (MAPK/ERK) signaling and cell proliferation in a Src and Ras dependent manner in cyst derived cells or in wild type tubular epithelial cells treated with Ca2+ channel blockers or in a low Ca2+ medium. Activation of tyrosine kinase receptors by ligands present in cystic fluid also contributes to the stimulation of MAPK/ERK signaling and cell proliferation. Phosphorylation of tuberin by ERK (or inadequate targeting to the plasma membrane due to defective interaction with polycystin 1) may lead to the dissociation of tuberin and hamartin and lead to the activation of Rheb and mTOR. TNFα acting on its receptor activates IKKb (inhibitor of kB kinase-b), which phosphorylates hamartin, suppressing TSC1-TSC2 function and activating mTOR. Activation of AMPK may blunt cystogenesis via inhibition of CFTR, inhibition of ERK, and phosphorylation of tuberin and inhibition of mTOR. Upregulation of Wnt signaling stimulates mTOR and β-catenin signaling. ERK and mTOR activation promotes G1/S transition and cell proliferation through regulation of cyclin D1, phosphorylation of retinoblastoma protein (RB) by CDK4/6-cyclin D and CDK2-cyclin E, and release E2F transcription factor. AC-VI, adenylate cyclase 6; AMPK, AMP kinase; CDK, cyclin dependent kinase; ER, endoplasmic reticulum; MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinase; mTOR, mammalian target of rapamycin; PC1, polycystin-1; PC2, polycystin-2; PDE, phosphodiesterase; PKA, protein kinase A; R, somatostatin sst2 receptor; TSC, tuberous sclerosis proteins tuberin (TSC2) and hamartin (TSC1); V2R, AVP V2R; V2RA, AVP V2R antagonists.

Increased levels of cAMP and expression of cAMP-dependent genes (such as AQP2 in the kidney) are a common finding in the kidneys of cpk, jck, pcy, KspCre;HNF1βflox/flox, Pkd2−/ws25, and γGT.Cre:Pkd1flox/flox mice and PCK rats,(25–27) liver of PCK rats,(28) vascular smooth muscle of Pkd2+/− mice, and choroid plexus of TG737orpk mice.(29) In view of the role of PC1 and PC2 in the regulation of intracellular calcium homeostasis and the importance of calcium in the regulation of cAMP metabolism by stimulation of calcium inhibitable adenylyl cyclase 6 and/or inhibition of calcium dependent phosphodiesterase 1, it has been suggested that alterations in intracellular calcium homeostasis account for the accumulation of cAMP (Figure 2). Up-regulation of the AVP V2 receptor (V2R) and high circulating AVP levels may contribute to the increased cAMP levels. Forskolin, an activator of adenylyl cyclase, may be synthesized by mural cyst epithelial cells, has been identified within the cyst fluid, and may contribute to the progression of PKD.(30)

In the cystic cells, chloride enters across basolateral NaK2Cl cotransporters, driven by the sodium gradient generated by basolateral Na-K-ATPase and exits across apical cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) (Figure 2). Basolateral recycling of potassium may occur via KCa3.1 channels.(31, 32) Active accumulation of chloride within the cyst lumen drives sodium and water secretion down transepithelial potential and osmotic gradients. This model for cyst fluid secretion requires a paracellular pathway sealed by tight junctions impermeable to chloride that remain intact even in late-stage cysts.(33)

While under normal conditions, cAMP inhibits MAP kinase signaling and cell proliferation, in PKD or in conditions of calcium deprivation it stimulates cell proliferation in a Src, Ras and B-raf dependent manner (Figure 2). The abnormal proliferative response to camp is directly linked to the alterations in [Ca2+]i, since it can be reproduced in wild-type cells by lowering [Ca2+]i. Conversely, Ca2+ ionophores or channel activators can rescue the abnormal response of cyst derived cells.(34) Cell proliferation can be further enhanced by stimulation of epidermal growth factor (EGF)-like factors present in cyst fluid, increased insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) in cystic tissues, and by activation of mTOR. ERK-dependent phosphorylation of tuberin prevents its association with hamartin and the inhibition of Rheb and mTOR by the tuberin-hamartin complex. Upregulation of TNFα or downregulation of AMPK signaling can also activate mTOR through inhibition of the tuberin-hamartin complex. Activation of AMPK may blunt cystogenesis via inhibition of CFTR and ERK. Upregulation of Wnt signaling stimulates mTOR and β-catenin signaling. ERK and mTOR activation promote G1/S transition and cell proliferation through regulation of cyclin D1, phosphorylation of retinoblastoma protein (rb) by cdk4/6-cyclin d and cdk2-cyclin e, and release e2F transcription factor.

Human and animal models of polycystic kidney disease exhibit an abnormal expression of matrix degrading enzymes and inhibitors of metalloproteinases, necessary for the remodeling of basement membranes and the surrounding extracellular matrix (ECM). Cyst lining epithelia produce large amounts of structural (collagen I and III, laminin) and soluble ECM-associated proteins (TGF-β, βig-H3, periostin) which accumulate around the cysts. Some ECM components (laminin, periostin) actively contribute to epithelial cell proliferation and cyst growth.(35–37)

Novel therapies

Potential targets for therapy in ADPKD include the genetic and molecular mechanisms responsible for cyst initiation, molecular mechanisms important for cyst growth, and less disease specific mechanisms contributing to progressive chronic kidney disease.

a) Genetic mechanisms and cyst initiation

Treatments directed at reducing the rate of somatic mutations contributing to cyst initiation can be considered. Their effectiveness would depend on whether the somatic mutations occur mostly during development, maturation and growth of the kidney or at later stages in association with environmental exposures and cellular senescence. Modeling based on data from CRISP suggests that most visible cysts in adults develop in utero in an environment that promotes extraordinary cellular proliferation.(38) This is consistent with observations in conditional knockouts showing that inactivation of Pkd1 in the early neonatal period result in the rapid formation of kidney cysts, whereas inactivation of Pkd1 in adult mice results in slow onset of kidney cysts.(10–12) If correct, this would limit the effectiveness of this strategy.

While high rates of cell proliferation make the developing kidney particularly susceptible to cystogenesis, environmental factors capable to stimulate tubular epithelial cell proliferation may increase the rate of cyst formation after maturation. Thus, ischemic reperfusion injury in conditional Kif3a or Pkd1 knockout mice and TNF-α administration to Pkd2+/− mice enhance cell proliferation and cyst formation.(14, 39, 40) Similarly, sustained elevated levels of circulating AVP, shown to stimulate the proliferation of renal tubular cells expressing V2Rs, enhances cyst development in PCK and PCK/Brattleboro rats.(41) Therefore, it is theoretically possible that environmental factors capable to induce a proliferative response may enhance cystogenesis, while interventions that limit tubular epithelial cell proliferation inhibit cyst development.

If ADPKD was a recessive disease at the cellular level, gene replacement therapy would be theoretically possible. The renal phenotype in the Oak Ridge National laboratory polycystic kidney (orpk) model can be rescued by the expression of the wild-type orpk gene as a transgene.(42) Expression of PKD1 as a transgene rescues the embryonically lethal phenotype in the Pkd1del34/del34 knock-out mouse.(43) Technical considerations, such as the requirement for a highly selective, efficient, and durable gene transfer to somatic cells, safety issues, and the observation that the overexpression of PKD1 or PKD2 also results in a cystic phenotype cast doubt on the feasibility of gene therapy as a successful treatment for ADPKD.

Stem cell therapy is not likely to work for ADPKD, as the cells introduced would need a proliferative advantage over the existing mutant cells.(44) Even then, it could not depend on an endogenous stem cell population, as these cells would carry the same mutation as the existing renal tissue.

b) Molecular mechanisms: Interventions focusing on cyst growth

Increasing understanding of how cysts grow and availability of orthologous animal models has facilitated the identification of promising targets and drugs to test in preclinical and clinical trials for ADPKD (Figure 2).

The effect of AVP, via V2Rs, on cAMP levels in the collecting duct and distal nephron, the major site of cyst development in ADPKD, and the role of cAMP in cystogenesis provided the rationale for preclinical trials of AVP V2R antagonists. OPC-31260, reduced the renal levels of cAMP and inhibited cyst development in models of ARPKD, ADPKD and nephronophthisis.(4) Administration to PCK rats and pcy mice at moderately advanced stages of the disease (starting at 10 and 15 weeks respectively) halted progression or induced regression. An antagonist with high potency and selectivity for the human VPV2R (tolvaptan) was also effective. There was no effect on liver cysts, consistent with the absence of VPV2R in the liver. High water intake also exerted a protective effect on the development of PKD in PCK rats likely due to suppression of AVP.(45) Genetic elimination of AVP in these rats yielded animals born with normal kidneys that remained relative free of cysts unless an exogenous V2R agonist was administered.(46) An antagonist of the endothelin-1 ETB receptor (predominant endothelin receptor subtype in the collecting tubules that inhibits AVP action and promotes diuresis) increased renal cAMP and aggravated the renal cystic disease in Pkd2WS25/− mice, presumably by enhancing the action of AVP.(47) Phase II clinical trials with tolvaptan have provided encouraging preliminary results.(48, 49) A phase III clinical trial is ongoing (NCT00428948).

Somatostatin acting on SST2 receptors inhibits cAMP accumulation in kidney and in liver.(50) Octreotide, a metabolically stable somatostatin analog, halted the expansion of hepatic cysts from PCK rats in vitro and in vivo.(28) Similar effects were observed in the kidneys. These observations are consistent with the inhibition of renal growth in a pilot study of long-acting octreotide for human ADPKD.(51) Small clinical trials (NCT00309283, NCT00426153, NCT00565097) have shown that administration of octreotide or lanreotide for periods of 6–12 months inhibits the growth of polycystic kidneys and livers.(52–54) Larger studies of longer duration are needed to confirm the safety and sustained efficacy of these treatments.

Since the hydrolytic capacity of cAMP phosphodiesterases exceeds the maximum rate of synthesis by adenylyl cyclases, activation of phosphodiesterases that regulate cAMP pools affecting fluid secretion and cell proliferation could be an alternative strategy to lower the cellular levels of cAMP. Recently a new class of compounds, the 2-(acylamino)-3-thiophenecarboxylates, that function as nonselective phosphodiesterase activators has been shown to inhibit the growth of MDCK cysts.(55) At present the efficacy of these compounds may be limited by their lack of selectivity and potential toxicity in vivo.

Correcting the alteration in intracellular calcium homeostasis thought to be responsible for the accumulation of cAMP and the proliferative phenotype of the cystic epithelium is a logical strategy to inhibit PKD development. Consistent with this is the aggravation of PKD in cy/+ rats by the administration of calcium channel blockers.(56) Triptolide (a biologically active compound isolated from the medicinal plant Tripterygium wilfordii) induced cellular calcium release through a PC2–dependent pathway, arrested growth of Pkd1−/− cells, and reduced cystic burden in embryonic and kidney-specific conditional Pkd1 knockout mice.(57, 58) A clinical trial of triptolide for ADPKD is currently active in China (NCT00801268).

At first sight, calcimimetics acting on the calcium sensing receptor (CaR) would seem to be excellent candidates to treat PKD. By coupling to Gq proteins, CaR activates phospholipase C-protein kinase C and mobilizes calcium from intracellular stores. By coupling to Gi proteins, it inhibits adenylyl cyclase-cAMP signaling. Unfortunately, type 2 calcimimetics did not inhibit cystogenesis in PCK rats and Pkd2WS25/− mice at early stages of disease, possibly because their effect on calcium-sensing receptors is outweighed by a reduction in extracellular calcium.(26).

The transporters required for chloride driven fluid secretion into the cysts (NaK2Cl cotransporter, Na-K-ATPase, CFTR, and KCa3.1) have been targeted to inhibit cyst growth. CFTR inhibitors slowed cyst growth in an MDCK cell culture model, in metanephric kidney organ cultures, and in Pkd1flox/−;Ksp-Cre mice.(59, 60) These observations are consistent with reports of families with both ADPKD and cystic fibrosis in which individuals with both diseases had less severe cystic disease than those with only ADPKD.(61) CFTR inhibitors that achieve high concentrations in the kidney and urine may find a place in the treatment of ADPKD because their accumulation in the lung is minimal and CFTR inhibition has to exceed 90% to affect lung function, thus making the development of cystic fibrosis–like lung disease unlikely.

A KCa3.1 inhibitor, TRAM-34 (an analogue of des-imidazolyl clotrimazole), inhibited forskolin stimulated transepithelial chloride secretion in filter-grown polarized monolayers of MDCK, NHK, and ADPKD cells, as well as MDCK and ADPKD cell cyst formation and enlargement in collagen gels.(31, 32) Although the efficacy of KCa3.1 inhibitors in ADPKD still needs to be demonstrated in animal models of the disease, it is encouraging that pharmacological inhibition or knockdown of KCa3.1 suppresses tubulointerstitial damage and protects functional renal parenchyma in an animal model of unilateral ureteral obstruction.(62) Senicapoc (ICA-17043), a KCa3.1 inhibitor, has been used successfully in a phase 2 trial and has shown little or no toxicity in a phase 3 trial for sickle cell disease.(63)

Targeting the NaK2Cl cotransporter or Na-K-ATPase to treat ADPKD seems less feasible because of likely side-effects and less predictable effects on cystogenesis. Inhibition of the NaK2Cl cotransporter could potentially be detrimental as hypokalemia has been associated with and chronic stimulation of COX-2 and PGE2 production may favor cyst development. Addition of relatively high concentrations of ouabain to basolateral but not apical membranes of ADPKD cell monolayers and intact cysts dissected from ADPKD kidneys inhibited fluid secretion. However, nanomolar concentrations of ouabain, within the range of levels found in blood under normal conditions, increase ERK phosphorylation and MEK-ERK dependent proliferation of ADPKD cells, without a significant effect on normal human kidney cells.(64)

Patients with the contiguous PKD1-TSC2 gene syndrome exhibit a more severe form of PKD than those with ADPKD alone. This observation suggests a convergence of signaling pathways downstream from PC1 and the TSC2 protein tuberin. Activation of mTOR in polycystic kidneys and an interaction between PC1 and tuberin have been reported.(65) Furthermore, studies in three rodent models of PKD have shown that the mTOR inhibitors sirolimus and/or everolimus significantly retard cyst expansion and protects renal function.(65–69) Small retrospective studies of ADPKD patients after transplantation have shown a significant reduction in the volume of the polycystic kidneys or polycystic liver in patients treated with sirolimus compared to patients treated with calcineurin inhibitors.(65, 70) Prospective, randomized clinical trials of rapamycin and everolimus are in progress (NCT00346918, NCT00491517, NCT00286156, NCT00414440).

It has been suggested that AMP-activated protein kinase activation might have a beneficial effect on the development of PKD since it directly phosphorylates and inhibits CFTR and inhibits mTOR via phosphorylation of tuberin (Figure 2). Consistent with this, metformin has been shown to reduce the growth of MDCK cysts and the cystic index of conditional kidney-specific Pkd1 knockout mouse.(71)

One of the effects of mTOR inhibition is to inhibit the production of and the cellular response to VEGF. VEGF is present in ADPKD liver and kidney cyst fluids and VEGF receptors 1 and 2 (VEGFR1 and VEGFR2) are present in cystic tissues. The results of VEGF inhibition in PKD have been mixed. Administration of the VEGFR inhibitor SU-5416 had a significant protective effect on the development of cystic disease in the liver, but not in the kidney, in a small number of Pkd2WS25/− mice.(72) On the other hand, treatment of developing CD-1 mice with antibodies against VEGFR2 results in the development of renal cysts, suggesting that inhibition of VEGF signaling could promote renal cyst growth.(73)

TNF-a, TNFR-I and TNF-a converting enzyme are over-expressed in cystic tissues. The administration of TNF promotes cyst formation in Pkd2+/− mice, whereas etanercept had an inhibitory effect.(39) An inhibitor of TNF-α-converting enzyme was shown to ameliorate the polycystic disease in the bpk mouse, a recessive model of PKD. The aggravation of PKD by TNFa may be due to its enhancement of the expression of FIP2, a protein that physically interacts with PC2 and prevents its transport to the plasma membrane and primay cilium. Alternatively, TNFa also activates IKKb (inhibitor of kB kinase-b), which physically interacts and phosphorylates hamartin, suppressing TSC1-TSC2 function and activating mTOR.(74)

PKD has been described as “neoplasm in disguise”. Many drugs developed to suppress cell proliferation and treat neoplastic diseases have been shown in animal models to be effective and of potential value for the treatment of ADPKD. These include Erb-B1 (EGF receptor) and Erb-B2 tyrosine kinase, Src kinase, MEK, and cdk inhibitors.(75–77) Roscovitine, a cyclin dependent kinase inhibitor, inhibited cystogenesis and improved renal function in two murine models of PKD, acting through blockade of the cell cycle, transcriptional regulation and inhibition of apoptosis.(78) Like PC1, roscovitine has been shown to increase the levels of p21, which is downregulated in PKD.(79)

Increased apoptosis accompanies increased cell proliferation in PKD, but it is unclear whether it is a neutral or beneficial consequence of excessive proliferation or an important contributor to cyst formation and renal injury. A caspase inhibitor (IDN-8050) reduced epithelial cell apoptosis and proliferation, and inhibited the development of the cystic disease and renal insufficiency in Han:SPRD rats.(69) Double mutants with PKD (cpk mice) and a knockout of caspase 3 had less severe cystic disease and lived longer than cpk mice with intact caspase 3.(80)

A number of studies have focused on the role of arachidonic acid metabolites and their inhibitors on the progression of PKD. Prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) accumulates in cyst fluids and enhances cAMP production and growth of MDCK cysts in collagen gels (81). PGE2 may act on four different G protein coupled receptors named E-prostanoid (EP) receptors 1–4. EP2 and EP4 are coupled to G stimulatory proteins and stimulate cAMP formation. EP3 is coupled to G inhibitory protein, inhibits cAMP formation, induces Rho activation and actin polymerization, and antagonizes AVP action. EP1 activation induces inositol 3-phosphate formation and calcium release. Recently, the effects of PGE2 on cAMP formation and cystogenesis, in a three-dimensional cell-culture system of human epithelial cells from normal and ADPKD kidneys, have been shown to be mediated by EP2 receptor activation, thus suggesting a possible role for EP2 receptor antagonists in the treatment of ADPKD.(81)

PLA, COX-1 and COX-2 activities and the production of prostacyclin, thromboxane A2 and PGE2 are higher in cystic than wild-type kidneys. Endogenous and steady-state in vitro levels of prostanoids were 2–10 times higher in diseased compared with normal kidneys. The administration of the COX-2 inhibitor NS-398 reduced cystic expansion by 18%, interstitial fibrosis by 67%, macrophage infiltration by 33%, cell proliferation by 38%, and presence of oxidized LDL by 59% compared to controls, but had no protective effect on renal function.(82)

The production of 20-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid (20-HETE), an endogenous cytochrome P450 metabolite of arachidonic acid with mitogenic properties, is markedly increased in microsomes from bpk compared to wild-type mice.(83) Daily administration of HET-0016, an inhibitor of 20-HETE synthesis, reduced kidney size by half and doubled survival. Transfection of principal cells isolated from wild-type mice with Cyp4a12 induced a four- to five-fold increase in cell proliferation, which was completely abolished when 20-HETE synthesis was inhibited. These observations suggest that 20-HETE contributes to the proliferation of epithelial cells in the formation of renal cysts and provide another potential target for intervention.

c) Molecular mechanisms: Late interventions

At advanced stages of the disease, mechanisms responsible for further progression may not be different from those operating in advanced stages of other renal diseases. Few preclinical trials have targeted PKD beyond early stages of the disease. Administration of the calcimimetic R-568, calcium gluconate or both to male cy/+ rats starting at 20 weeks of age had no effect on the severity of cystic disease or renal function at 34 weeks of age, but prevented the rapid progression of the cystic disease, development of interstitial fibrosis, and deterioration of renal function that occurred in the untreated animals between 34 and 38 weeks of age, coinciding with a three-fold increase in serum PTH levels.(84) R-568 inhibits CKD progression in subtotally nephrectomized rats to an extent similar to that observed with parathyroidectomy or administration of calcitriol.(85, 86) These studies suggest that the major, if not the only, factor explaining the effect of R-568 on CKD progression in the presence or absence of PKD is the decrease in the serum PTH concentration. Another study cy/+ rats showed that administration of a converting enzyme inhibitor for up to 40 weeks reduced kidney growth and proteinuria and protected renal function.(87) Other anti-inflammatory and antifibrotic therapies may be effective at advanced stages of the disease.

Challenges in the design of a clinical trial for ADPKD

In planning for clinical trials for ADPKD, selection of an appropriate primary outcome becomes an issue. A composite endpoint to 50% reduction in GFR, ESRD or death is most commonly used for trials in chronic kidney disease. Most ADPKD patients, however, maintain a GFR within the normal range, despite relentless growth of cysts, until the 4th to 6th decade of life. Interventional trials at early stages of the disease would require unrealistic periods of follow-up if GFR was to be used as the primary outcome. By the time renal function starts declining, the kidneys usually are markedly enlarged and distorted with little recognizable parenchyma on imaging studies. At this late stage, the decline in GFR that occurs at an average rate of 4.4–5.9 mL/min/year may be mostly due to non-specific mechanisms of CKD progression.(88) This makes detection of a benefit from therapies directed at specific ADPKD targets much less likely.

CRISP has shown that kidney volume is the strongest predictor of renal functional decline in ADPKD(1, 4), confirming previous cross-sectional and longitudinal studies. Kidney volume is also associated with the development of hypertension and symptoms such as pain and hematuria. CRISP has also shown that changes in renal volume can be accurately detected over relatively short periods of time. Therefore, a strong argument can be made for the utilization of kidney volume as a surrogate marker of disease progression in clinical trials for ADPKD. At present, however, regulatory agencies do not accept volume as a satisfactory primary end-point because a causal relation between renal enlargement and renal function decline (i.e. demonstration that renal function decline does not occur when renal enlargement is prevented) has not been proven.

The HALT-PKD Trials, a model for early and late interventional trials

HALT-PKD consists of two NIH/NIDDK funded, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled trials developed to investigate the impact of intensive blockade of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system and level of BP control on progressive renal disease in hypertensive ADPKD patients at early (Study A) and late (Study B) stages of the disease. With study end-points appropriate for each stage of the disease, a positive intervention for either study would translate into years of life gained without dialysis in this population. Details of the study design and implementation have been published.(89)

In Study A, 558 participants with an eGFR >60 mL/min/1.73 m2 have been randomized to one of four conditions in a 2-by-2 design: angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor (ACE-I)/angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB) combination therapy at two levels of blood pressure control (standard, systolic 120–130 and diastolic 70–80 mm Hg vs. low, systolic 95–110 and diastolic 60–75 mm Hg) or ACE-I monotherapy at the same two levels of blood pressure control. The primary outcome is percent change in total kidney volume measured by MRI. Secondary measures include changes in left ventricular mass index and renal blood flow by MRI, albumin excretion and eGFR. Power estimates were based on data from the CRISP study. A sample size of 548 participants has 90% power for detecting a 25% reduction from 5.4 to 4.1% per year change in total kidney volume for subjects treated with combination versus mono therapy, with a significance level of 0.05 (two-tailed), assuming a 15% loss of follow-up information on enrolled subjects.

In Study B, 486 participants with an eGFR 25–60 mL/min/1.73 m2 have been randomized to ACE-I/ARB combination therapy or ACE-I monotherapy, with both groups treated to a standard level of blood pressure control (systolic 110–130 mm Hg and diastolic <80 mm Hg). The primary outcome is a composite endpoint of time to 50% reduction of baseline eGFR, ESRD or death. Power estimates were based on data from the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease (MDRD) study. A sample size of 470 subjects has 0.90 power to detect a slowing in the rate of change of eGFR by 25%, with a significance level of 0.05 (two-tailed), assuming a 15% loss of follow-up information on enrolled subjects.

In summary, recent advances in the understanding of the genetic and molecular mechanisms and the natural history of ADPKD have made possible the development of therapies designed to slow down the progression of ADPKD. Some are currently being tested in clinical trials (Table 1). Identification of patients most likely to benefit from treatment, those with rapid disease progression, at relatively early stages has become possible. The important role of cAMP in cystogenesis and the ability to hormonally modulate cAMP signaling in a tissue/cell-specific manner provide a strategy that minimizes adverse effects on unaffected tissues or cells, obviously very important when considering treatments for a chronic disease such as ADPKD. Combination therapies also may provide opportunities to maximize efficiency and minimize adverse events. Interventions capable to slow down, stop or reverse structural progression of the disease will need to be proven capable to prevent decline of renal function and improve clinically significant outcomes.

Table 1.

Currently active clinical trials for ADPKD

| Intervention | Study design | Eligibility* | Enrollment Target and Primary Outcome Measure | Start- Finish Dates | Sponsor | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HALT-PKD Study A Phase 3 NCT00283686 |

Lisinopril/telmisartan vs lisinopril/placebo and low vs standard BP target | Multi-center, randomized, double blind, placebo control, 2×2 factorial assignment | 15–49 y.o. GFR >60 BP ≥130/80 or treatment for HT |

548 Kidney volume change (MRI) |

2006–2013 | NIDDK |

| HALT-PKD Study B Phase 3 NCT00283686 |

Lisinopril/telmisartan vs lisinopril/placebo | Multi-center, randomized, double blind, placebo control | 18–64 y.o. GFR 25–60 BP ≥130/80 or treatment for HT |

470 Time to the 50% reduction in eGFR, ESRD or death |

2006–2013 | NIDDK |

| Effect of Statin on Disease Progression Phase 3 NCT00456365 |

Pravastatin | Randomized, double blind, placebo control | 8–21 y.o, Normal GFR | 100 Kidney volume, LVMI, urine albumin, endothelial dependent vasodilation |

2006–2011 | U. of Colorado |

| TEMPO 2/4 Trial Phase 2 NCT00413777 |

V2 receptor antagonist (tolvaptan) | Multi-center, open-label, dose comparison | >18 y.o. Participation in prior dose- finding studies |

48 Long-term safety (kidney volume sec. outcome) |

2005–2008 | Otsuka Pharm. |

| TEMPO 3/4 Trial Phase 3 NCT00428948 |

V2 receptor antagonist (tolvaptan) | Multi-center, double-blind, placebo control | 18–40 y.o. GFR≥60 TKV ≥750 ml |

1500 Kidney volume change (MRI) |

2007–2011 | Otsuka Pharm. |

| Octreotide in ADPKD Phase 3 NCT00309283 |

Long-acting somatostatin (octreotide) | Randomized, single blind, placebo control | 18–75 y.o. GFR >40 |

66 Kidney volume change (MRI) |

2006–2010 | Mario Negri Institute |

| Octreotide in severe PLD Phase 2-3 NCT00426153 |

Long-acting somatostatin (octreotide) | Randomized, double-blind, placebo control, crossover | >18 y.o. LV>4,000 ml or highly symptomatic PLD |

42 Liver volume change (MRI) (kidney volume sec. outcome) |

2007–2010 (open label extension) | Mayo Clinic, Novartis |

| Lanreotide in PLD Phase 2-3 NCT00565097 |

Long-acting somatostatin (lanreotide) | Randomized, double blind, placebo control | >18 y.o. >20 liver cysts |

38 Liver volume change (CT) |

2007–2009 (open label extension) | Radboud University, Ipsen Ltd. |

| SUISSE Study Phase 3 NCT00346918 |

mTOR inhibitor (sirolimus) | Multi-center, randomized, single blind, placebo control | 18–40 y.o. GFR ≥70 |

100 Kidney volume change (MRI) |

2006–2010 | U. of Zurich |

| SIRENA Study Phase 2 NCT00491517 |

mTOR inhibitor (sirolimus) | Randomized, open label, crossover | 18–80 y.o. GFR ≥70 |

16 Kidney volume change (CT) |

2007–2009 | Mario Negri Institute |

| Sirolimus in ADPKD Phase 1-2 NCT00286156 |

mTOR inhibitor (sirolimus) | Randomized, open label, dose comparison | 18–75 y.o. | 45 Iothalamate GFR change |

Cleveland Clinic | |

| Everolimus in ADPKD Phase 3 NCT00414440 |

mTOR inhibitor (everolimus) | Multicenter, randomized, placebo control, double-blind | 18–65 y.o. GFR≥60 |

400 Kidney volume change (MRI) |

2006–2009 | Novartis |

| PLD in Kidney Transplant Phase 2-3 NCT00934791 |

mTOR inhibitor (sirolimus) | Randomized, open label | >18 y.o. Primary kidney transplant Liver volume 2.5–7.5 L |

68 Liver volume change (MRI) |

2009–2015 | Mayo Clinic/Wyeth |

| Triptolide in ADPKD Phase 2 NCT00801268 |

Triptolide | Randomized, open label | 15–70 y.o. eGFR>70 |

150 Kidney volume change (MRI), eGFR |

2008–2011 | Nanjing University |

| ADPKD Pain Study Phase 2 NCT00571909 |

Videothoracoscopic sympatho- splanchnicectomy | Non- randomized, open label, uncontrolled | >18 y.o. Debilitating kidney pain |

20 Pain control and quality of life |

2007–2010 | Mayo Clinic, PKDF |

GFR, estimated or measured, in mL/min or ml/min/1.73 m2; BP in mmHg.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement: Dr. Torres is an investigator in clinical trials supported by Otsuka, Novartis, and Wyeth Pharmaceuticals.

References

- 1.Grantham JJ, Torres VE, Chapman AB, et al. Volume progression in polycystic kidney disease. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:2122–2130. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa054341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grantham JJ, Cook LT, Torres VE, et al. Determinants of renal volume in autosomal-dominant polycystic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2008;73(1):108–116. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5002624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kistler AD, Poster D, Krauer F, et al. Increases in kidney volume in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease can be detected within 6 months. Kidney Int. 2009;75(2):235–241. doi: 10.1038/ki.2008.558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Torres VE, King BF, Chapman AB, et al. Magnetic resonance measurements of renal blood flow and disease progression in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;2(1):112–120. doi: 10.2215/CJN.00910306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jiang ST, Chiou YY, Wang E, et al. Defining a link with autosomal-dominant polycystic kidney disease in mice with congenitally low expression of Pkd1. Am J Pathol. 2006;168(1):205–220. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.050342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thivierge C, Kurbegovic A, Couillard M, Guillaume R, Cote O, Trudel M. Overexpression of PKD1 causes polycystic kidney disease. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26(4):1538–1548. doi: 10.1128/MCB.26.4.1538-1548.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Park EY, Sung YH, Yang MH, et al. CYST formation kidney via B-RAF signaling in the PKD2 transgenic mice. J Biol Chem. 2008 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M805890200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burtey S, Riera M, Ribe E, et al. Overexpression of PKD2 in the mouse is associated with renal tubulopathy. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2008;23(4):1157–1165. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfm763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gallagher AR, Hoffmann S, Brown N, et al. A truncated polycystin-2 protein causes polycystic kidney disease and retinal degeneration in transgenic rats. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 2006;17(10):2719–2730. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2005090979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Davenport JR, Watts AJ, Roper VC, et al. Disruption of intraflagellar transport in adult mice leads to obesity and slow-onset cystic kidney disease. Curr Biol. 2007;17(18):1586–1594. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.08.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Piontek K, Menezes LF, Garcia-Gonzalez MA, Huso DL, Germino GG. A critical developmental switch defines the kinetics of kidney cyst formation after loss of Pkd1. Nat Med. 2007;13(12):1490–1495. doi: 10.1038/nm1675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lantinga-van Leeuwen IS, Leonhard WN, van der Wal A, Breuning MH, de Heer E, Peters DJ. Kidney-specific inactivation of the Pkd1 gene induces rapid cyst formation in developing kidneys and a slow onset of disease in adult mice. Hum Mol Genet. 2007;16(24):3188–3196. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddm299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Takakura A, Contrino L, Beck AW, Zhou J. Pkd1 inactivation induced in adulthood produces focal cystic disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;19(12):2351–2363. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2007101139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Patel V, Li L, Cobo-Stark P, et al. Acute kidney injury and aberrant planar cell polarity induce cyst formation in mice lacking renal cilia. Hum Mol Genet. 2008;17(11):1578–1590. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Low SH, Vasanth S, Larson CH, et al. Polycystin-1, STAT6, and P100 function in a pathway that transduces ciliary mechanosensation and is activated in polycystic kidney disease. Dev Cell. 2006;10(1):57–69. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lal M, Song X, Pluznick JL, et al. Polycystin-1 C-terminal tail associates with beta-catenin and inhibits canonical Wnt signaling. Hum Mol Genet. 2008;17(20):3105–3117. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Koulen P, Cai Y, Geng L, et al. Polycystin-2 is an intracellular calcium release channel. Nat Cell Biol. 2002;4:191–197. doi: 10.1038/ncb754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li Y, Wright JM, Qian F, Germino GG, Guggino WB. Polycystin 2 interacts with type I inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor to modulate intracellular Ca2+ signaling. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(50):41298–41306. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M510082200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Anyatonwu GI, Estrada M, Tian X, Somlo S, Ehrlich BE. Regulation of ryanodine receptor-dependent calcium signaling by polycystin-2. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(15):6454–6459. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610324104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aguiari G, Trimi V, Bogo M, et al. Novel role for polycystin-1 in modulating cell proliferation through calcium oscillations in kidney cells. Cell Prolif. 2008;41(3):554–573. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2184.2008.00529.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Weber KH, Lee EK, Basavanna U, et al. Heterologous expression of polycystin-1 inhibits endoplasmic reticulum calcium leak in stably transfected MDCK cells. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2008;294(6):F1279–1286. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00348.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xu C, Rossetti S, Jiang L, et al. Human ADPKD primary cyst epithelial cells with a novel, single codon deletion in the PKD1 gene exhibit defective ciliary polycystin localization and loss of flow-induced Ca2+ signaling. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2007;292(3):F930–945. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00285.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wegierski T, Steffl D, Kopp C, et al. TRPP2 channels regulate apoptosis through the Ca(2+) concentration in the endoplasmic reticulum. EMBO J. 2009 doi: 10.1038/emboj.2008.307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Geng L, Boehmerle W, Maeda Y, et al. Syntaxin 5 regulates the endoplasmic reticulum channel-release properties of polycystin-2. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105(41):15920–15925. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805062105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Smith LA, Bukanov NO, Husson H, et al. Development of polycystic kidney disease in juvenile cystic kidney mice: insights into pathogenesis, ciliary abnormalities, and common features with human disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17(10):2821–2831. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006020136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang X, Harris PC, Somlo S, Batlle D, Torres VE. Effect of calcium-sensing receptor activation in models of autosomal recessive or dominant polycystic kidney disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2009;24(2):526–534. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfn527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Starremans PG, Li X, Finnerty PE, et al. A mouse model for polycystic kidney disease through a somatic in-frame deletion in the 5′ end of Pkd1. Kidney Int. 2008;73(12):1394–1405. doi: 10.1038/ki.2008.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Masyuk TV, Masyuk AI, Torres VE, Harris PC, Larusso NF. Octreotide inhibits hepatic cystogenesis in a rodent model of polycystic liver disease by reducing cholangiocyte adenosine 3′,5′-cyclic monophosphate. Gastroenterology. 2007;132(3):1104–1116. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.12.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Banizs B, Komlosi P, Bevensee MO, Schwiebert EM, Bell PD, Yoder BK. Altered pHi regulation and Na+/HCO3− transporter activity in choroid plexus of cilia-defective Tg737orpk mutant mouse. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2007;292(4):C1409–1416. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00408.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Putnam WC, Swenson SM, Reif GA, Wallace DP, Helmkamp GM, Jr, Grantham JJ. Identification of a forskolin-like molecule in human renal cysts. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;18(3):934–943. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006111218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Albaqumi M, Srivastava S, Li Z, et al. KCa3.1 potassium channels are critical for cAMP-dependent chloride secretion and cyst growth in autosomal-dominant polycystic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2008;74(6):740–749. doi: 10.1038/ki.2008.246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Alper SL. Let’s look at cysts from both sides now. Kidney Int. 2008;74(6):699–702. doi: 10.1038/ki.2008.357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yu AS, Kanzawa SA, Usorov A, Lantinga-van Leeuwen IS, Peters DJ. Tight junction composition is altered in the epithelium of polycystic kidneys. J Pathol. 2008;216(1):120–128. doi: 10.1002/path.2392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yamaguchi T, Hempson SJ, Reif GA, Hedge AM, Wallace DP. Calcium restores a normal proliferation phenotype in human polycystic kidney disease epithelial cells. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17(1):178–187. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2005060645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wallace DP, Quante MT, Reif GA, et al. Periostin induces proliferation of human autosomal dominant polycystic kidney cells through alphaV-integrin receptor. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2008;295(5):F1463–1471. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.90266.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Joly D, Berissi S, Bertrand A, Strehl L, Patey N, Knebelmann B. Laminin 5 regulates polycystic kidney cell proliferation and cyst formation. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(39):29181–29189. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M606151200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shannon MB, Patton BL, Harvey SJ, Miner JH. A hypomorphic mutation in the mouse laminin alpha5 gene causes polycystic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17(7):1913–1922. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2005121298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Grantham JJ, Cook LT, Cadnapaphornchai MA, Bae KT. Evidence of extraordinary mural cell proliferation and cyst growth during the early development of renal cysts in ADPKD. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20:494A. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li X, Magenheimer BS, Xia S, et al. A tumor necrosis factor-alpha-mediated pathway promoting autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Nat Med. 2008;14(8):863–868. doi: 10.1038/nm1783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Takakura A, Contrino L, Zhou X, et al. Renal injury is a third hit promoting rapid development of adult polycystic kidney disease. Hum Mol Genet. 2009;18(14):2523–2531. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Alonso G, Galibert E, Boulay V, et al. Sustained elevated levels of circulating vasopressin selectively stimulate the proliferation of kidney tubular cells via the activation of V2 receptors. Endocrinology. 2009;150(1):239–250. doi: 10.1210/en.2008-0068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yoder B, Richards W, Sommardahl C, et al. Functional correction of renal defects in a mouse model for ARPKD through expression of the cloned wild-type Tg737 cDNA. Kidney Int. 1996;50:1240–1248. doi: 10.1038/ki.1996.433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pritchard L, Sloane-Stanley JA, Sharpe J, et al. A human PKD1 transgene generates functional polycystin-1 in mice and is associated with a cystic phenotype. Hum Mol Genet. 2000;9:2617–2627. doi: 10.1093/hmg/9.18.2617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hopkins C, Li J, Rae F, Little MH. Stem cell options for kidney disease. J Pathol. 2009;217(2):265–281. doi: 10.1002/path.2477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nagao S, Nishii K, Katsuyama M, et al. Increased water intake decreases progression of polycystic kidney disease in the PCK rat. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17(8):2220–2227. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006030251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang X, Wu Y, Ward CJ, Harris PC, Torres VE. Vasopressin directly regulates cyst growth in the PCK rat. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;19(1):102–108. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2007060688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chang MY, Parker E, El Nahas M, Haylor JL, Ong AC. Endothelin B receptor blockade accelerates disease progression in a murine model of autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;18(2):560–569. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006090994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Torres VE, Winklhofer F, Chapman AB, et al. Phase 2 open-label study to determine long-term safety, tolerability and efficiacy of split-dose Tolvaptan in ADPKD. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20:746A. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Higashihara E, Nutahara K, Horie S, Gejyo F, Hishida A. An open label long-term administration study of tolvaptan in patients with autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD) in Japan. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20:746A. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Masyuk AI, Masyuk TV, Splinter PL, Huang BQ, Stroope AJ, LaRusso NF. Cholangiocyte cilia detect changes in luminal fluid flow and transmit them into intracellular Ca2+ and cAMP signaling. Gastroenterology. 2006;131(3):911–920. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ruggenenti P, Remuzzi A, Ondei P, et al. Safety and efficacy of long-acting somatostatin treatment in autosomal dominant polcysytic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2005;68:206–216. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.00395.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Caroli A, Antiga L, Cafaro M, et al. Reducing polycystic liver volume in ADPKD: Effects of extended release somatostatin. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20:497A. doi: 10.2215/CJN.05380709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hogan MC, Masyuk T, Kim B, et al. A pilot study of long-acting Octreotide (Octreotide LAR® Depot) in the treatment of patients with severe polycystic liver disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20:29A. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Keimpema LV, Nevens F, Vanslembrouck R, et al. Lanreotide reduces the volume of polycystic liver: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Gastroenterology. 2009;137:1661–1668. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.07.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tradtrantip L, Yangthara B, Padmawar P, Morrison C, Verkman AS. Thiophenecarboxylate suppressor of cyclic nucleotides discovered in a small-molecule screen blocks toxin-induced intestinal fluid secretion. Mol Pharmacol. 2009;75(1):134–142. doi: 10.1124/mol.108.050567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nagao S, Nishii K, Yoshihara D, et al. Calcium channel inhibition accelerates polycystic kidney disease progression in the Cy/+ rat. Kidney Int. 2008;73(3):269–277. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5002629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Leuenroth SJ, Bencivenga N, Igarashi P, Somlo S, Crews CM. Triptolide reduces cystogenesis in a model of ADPKD. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;19(9):1659–1662. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2008030259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Leuenroth SJ, Okuhara D, Shotwell JD, et al. Triptolide is a traditional Chinese medicine-derived inhibitor of polycystic kidney disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(11):4389–4394. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700499104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Magenheimer BS, St John PL, Isom KS, et al. Early embryonic renal tubules of wild-type and polycystic kidney disease kidneys respond to cAMP stimulation with cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator/Na(+), K(+),2Cl(−) Co-transporter-dependent cystic dilation. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17(12):3424–3437. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006030295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yang B, Sonawane ND, Zhao D, Somlo S, Verkman AS. Small-molecule CFTR inhibitors slow cyst growth in polycystic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;19(7):1300–1310. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2007070828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Xu N, Glockner JF, Rossetti S, Babovich-Vuksanovic D, Harris PC, Torres VE. Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease coexisting with cystic fibrosis. J Nephrol. 2006;19(4):529–534. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Grgic I, Kiss E, Kaistha BP, et al. Renal fibrosis is attenuated by targeted disruption of KCa3.1 potassium channels. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106(34):14518–14523. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0903458106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ataga KI, Smith WR, De Castro LM, et al. Efficacy and safety of the Gardos channel blocker, senicapoc (ICA-17043), in patients with sickle cell anemia. Blood. 2008;111(8):3991–3997. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-08-110098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Nguyen AN, Wallace DP, Blanco G. Ouabain Binds with High Affinity to the Na, K-ATPase in Human Polycystic Kidney Cells and Induces Extracellular Signal-Regulated Kinase Activation and Cell Proliferation. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;18(1):46–57. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006010086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Shillingford JM, Murcia NS, Larson CH, et al. The mTOR pathway is regulated by polycystin-1, and its inhibition reverses renal cystogenesis in polycystic kidney disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103(14):5466–5471. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509694103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wahl PR, Serra AL, Le Hir M, Molle KD, Hall MN, Wuthrich RP. Inhibition of mTOR with sirolimus slows disease progression in Han:SPRD rats with autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD) Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2006;21(3):598–604. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfi181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wu M, Wahl PR, Le Hir M, Wackerle-Men Y, Wuthrich RP, Serra AL. Everolimus retards cyst growth and preserves kidney function in a rodent model for polycystic kidney disease. Kidney & Blood Pressure Research. 2007;30(4):253–259. doi: 10.1159/000104818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Berthier CC, Wahl PR, Le Hir M, et al. Sirolimus ameliorates the enhanced expression of metalloproteinases in a rat model of autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2008;23(3):880–889. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfm697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Edelstein CL. Mammalian target of rapamycin and caspase inhibitors in polycystic kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;3(4):1219–1226. doi: 10.2215/CJN.05611207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Qian Q, Du H, King BF, et al. Sirolimus reduces polycystic liver volume in ADPKD patients. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;19(3):631–638. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2007050626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Takiar V, Nishio S, King JD, Hallows KR, Somlo S, Caplan MJ. Metformin activation of AMPK slows renal cystogenesis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;19:26A. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Amura CR, Brodsky KS, Groff R, Gattone VH, Voelkel NF, Doctor RB. VEGF receptor inhibition blocks liver cyst growth in pkd2(WS25/−) mice. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2007;293(1):C419–428. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00038.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.McGrath-Morrow S, Cho C, Molls R, et al. VEGF receptor 2 blockade leads to renal cyst formation in mice. Kidney Int. 2006;69(10):1741–1748. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5000314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Lee DF, Kuo HP, Chen CT, et al. IKKbeta suppression of TSC1 function links the mTOR pathway with insulin resistance. International journal of molecular medicine. 2008;22(5):633–638. doi: 10.3892/ijmm_00000065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Wilson SJ, Amsler K, Hyink DP, et al. Inhibition of HER-2(neu/ErbB2) restores normal function and structure to polycystic kidney disease (PKD) epithelia. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1762:647–655. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2006.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Sweeney WE, Jr, von Vigier RO, Frost P, Avner ED. Src inhibition ameliorates polycystic kidney disease. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 2008;19(7):1331–1341. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2007060665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Omori S, Hida M, Fujita H, et al. Extracellular signal-regulated kinase inhibition slows disease progression in mice with polycystic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17(6):1604–1614. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2004090800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Bukanov NO, Smith LA, Klinger KW, Ledbetter SR, Ibraghimov-Beskrovnaya O. Long-lasting arrest of murine polycystic kidney disease with CDK inhibitor roscovitine. Nature. 2006;444(7121):949–952. doi: 10.1038/nature05348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Park JY, Schutzer WE, Lindsley JN, et al. p21 is decreased in polycystic kidney disease and leads to increased epithelial cell cycle progression: roscovitine augments p21 levels. BMC Nephrol. 2007;8:12. doi: 10.1186/1471-2369-8-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Tao Y, Zafar I, Kim J, Schrier RW, Edelstein CL. Caspase-3 gene deletion prolongs survival in polycystic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;19(4):749–755. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006121378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Elberg G, Elberg D, Lewis TV, et al. EP2 receptor mediates PGE2-induced cystogenesis of human renal epithelial cells. American Journal of Physiology - Renal Physiology. 2007;293(5):F1622–1632. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00036.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Sankaran D, Bankovic-Calic N, Ogborn MR, Crow G, Aukema HM. Selective COX-2 inhibition markedly slows disease progression and attenuates altered prostanoid production in Han:SPRD-cy rats with inherited kidney disease. American Journal of Physiology - Renal Physiology. 2007;293(3):F821–830. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00257.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Park F, Sweeney WE, Jia G, Roman RJ, Avner ED. 20-HETE mediates proliferation of renal epithelial cells in polycystic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;19(10):1929–1939. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2007070771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Gattone VH, II, Chen NX, Sinders R, et al. Calcimimetic inhibition of late stage renal cystic pathology in a rat model of autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009 (in press) [Google Scholar]

- 85.Ogata H, Ritz E, Odoni G, Amann K, Orth SR. Beneficial effects of calcimimetics on progression of renal failure and cardiovascular risk factors. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2003;14(4):959–967. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000056188.23717.e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Piecha G, Kokeny G, Nakagawa K, et al. Calcimimetic R-568 or calcitriol: equally beneficial on progression of renal damage in subtotally nephrectomized rats. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2008;294(4):F748–757. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00220.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Kennefick T, Al-Nimri M, Oyama T, et al. Hypertension and renal injury in experimental polycystic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 1999;56(6):2181–2190. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1999.00783.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Klahr S, Breyer J, Beck G, et al. Dietary protein restriction, blood pressure control, and the progression of polycystic kidney disease modification of diet in renal disease study group. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1995;5(12):2037–2047. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V5122037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Chapman AB, Torres VE, Perrone RD, et al. The HALT polycystic kidney disease trials: Design and implementation. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010 doi: 10.2215/CJN.04310709. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]