Abstract

Background

Cryptococcal meningitis accounts for 20 to 25% of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome–related deaths in Africa. Antiretroviral therapy (ART) is essential for survival; however, the question of when ART should be initiated after diagnosis of cryptococcal meningitis remains unanswered.

Methods

We assessed survival at 26 weeks among 177 human immunodeficiency virus–infected adults in Uganda and South Africa who had cryptococcal meningitis and had not previously received ART. We randomly assigned study participants to undergo either earlier ART initiation (1 to 2 weeks after diagnosis) or deferred ART initiation (5 weeks after diagnosis). Participants received amphotericin B (0.7 to 1.0 mg per kilogram of body weight per day) and fluconazole (800 mg per day) for 14 days, followed by consolidation therapy with fluconazole.

Results

The 26-week mortality with earlier ART initiation was significantly higher than with deferred ART initiation (45% [40 of 88 patients] vs. 30% [27 of 89 patients]; hazard ratio for death, 1.73; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.06 to 2.82; P = 0.03). The excess deaths associated with earlier ART initiation occurred 2 to 5 weeks after diagnosis (P = 0.007 for the comparison between groups); mortality was similar in the two groups thereafter. Among patients with few white cells in their cerebrospinal fluid (<5 per cubic millimeter) at randomization, mortality was particularly elevated with earlier ART as compared with deferred ART (hazard ratio, 3.87; 95% CI, 1.41 to 10.58; P = 0.008). The incidence of recognized cryptococcal immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome did not differ significantly between the earlier-ART group and the deferred-ART group (20% and 13%, respectively; P = 0.32). All other clinical, immunologic, virologic, and microbiologic outcomes, as well as adverse events, were similar between the groups.

Conclusions

Deferring ART for 5 weeks after the diagnosis of cryptococcal meningitis was associated with significantly improved survival, as compared with initiating ART at 1 to 2 weeks, especially among patients with a paucity of white cells in cerebrospinal fluid. (Funded by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases and others; COAT ClinicalTrials.gov number, NCT01075152.)

Cryptococcus neoformans is the most common cause of meningitis in adults in sub-Saharan Africa,1–5 and meningitis caused by C. neoformans accounts for approximately 20 to 25% of deaths from the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) in Africa.6–9 Determining when antiretroviral therapy (ART) should be initiated after a diagnosis of cryptococcal meningitis involves balancing the survival benefit conferred by ART against the risk of the immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome (IRIS), a paradoxical reaction that occurs during immunologic recovery with ART despite effective therapy for the opportunistic infection. Since 2009, the international standard of care has shifted toward earlier ART initiation after diagnosis of an opportunistic infection; most of the evidence in support of this strategy is for tuberculosis, particularly in persons with CD4 cell counts lower than 50 per cubic millimeter.10–13

Conflicting data regarding the relationship between the timing of ART for cryptococcosis and the outcome pose a therapeutic dilemma. Three randomized trials have differed with respect to both the timing of ART initiation and the results.13–15 The AIDS Clinical Trials Group A5164 trial, involving 41 U.S. and South African participants with cryptococcosis who were receiving amphotericin-based treatment, showed nonsignificant decreases in the rates of death and AIDS progression among those who were randomly assigned to earlier ART initiation (<14 days after diagnosis; median, 12 days), as compared with those assigned to deferred ART initiation (>28 days after diagnosis; median, 45 days).13,16 In contrast, in a group of 54 patients in Zimbabwe treated with fluconazole monotherapy (800 mg per day), mortality was higher among those randomly assigned to immediate ART (median, <24 hours) than among those assigned to deferred ART (median, 10 weeks).14 A third randomized trial, involving 27 patients in Botswana, showed no significant difference in the survival rate but a higher incidence of IRIS with earlier ART.15 All three trials were underpowered to provide definitive guidance. In addition, earlier ART has been found not to be beneficial for tuberculous meningitis17; thus, the timing of ART that provides the greatest therapeutic benefit in patients with central nervous system (CNS) infections may differ from the timing in patients with non-CNS infections.

We designed the Cryptococcal Optimal ART Timing (COAT) Trial to determine whether earlier or deferred ART confers a survival benefit, given the equipoise between the risk of cryptococcal IRIS and the benefit of ART. After initiation of ART, cryptococcal IRIS occurs in approximately 14 to 30% of persons whose cryptococcosis has been successfully treated.10,11 IRIS may be fatal when it occurs in the brain.18, 19 However, earlier ART initiation is beneficial after opportunistic infections not involving the CNS.10–13 We hypothesized that ART initiation 1 to 2 weeks after diagnosis of cryptococcal meningitis, during the second week of amphotericin-based therapy in the hospital, would improve the 26-week survival rate, as compared with ART initiation at approximately 5 weeks after diagnosis, provided on an outpatient basis.

methods

Study Population and Setting

We enrolled patients at Mulago Hospital, Kampala, and Mbarara Hospital, Mbarara — both in Uganda — and at GF Jooste Hospital in Cape Town, South Africa, beginning in November 2010, February 2011, and April 2011, respectively. Patients with suspected meningitis were screened at the time of hospital presentation and counseled regarding cryptococcosis, HIV and AIDS, ART, and possible research participation. Eligibility criteria for enrollment were an age of 18 years or older, a diagnosis of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, no previous receipt of ART, a diagnosis of cryptococcal meningitis based on cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) culture or CSF cryptococcal antigen assay, and treatment with amphotericin-based therapy. Exclusion criteria were an inability to undergo follow-up, contraindication for or refusal to undergo lumbar punctures, multiple concurrent CNS infections, previous cryptococcosis, receipt of chemotherapy or immunosuppressive agents, pregnancy, breast-feeding, and serious coexisting conditions that precluded random assignment to earlier or deferred ART. Women included in the study agreed to use two forms of contraception, because high-dose fluconazole is potentially teratogenic during the first trimester of pregnancy. Written informed consent was obtained from each participant or his or her surrogate. The institutional review board at each participating site approved the study.

Study Treatment

Patients entered the trial after 7 to 11 days of antifungal treatment. Participants were randomly assigned to receive either ART initiated within 48 hours after randomization (earlier-ART group) or ART initiated 4 weeks after randomization (deferred-ART group). Cryptococcal induction therapy consisted of 2 weeks of treatment with amphotericin B (0.7 to 1.0 mg per kilogram of body weight per day) combined with fluconazole (800 mg per day), a regimen that is consistent with international guidelines.20,21 Flucytosine, although it is the most effective drug to combine with amphotericin, is unavailable in low-income and middle-income countries.22,23 Enhanced consolidation therapy consisted of 800 mg of fluconazole per day for at least 3 weeks or until a CSF culture was sterile, followed by 400 mg of fluconazole per day thereafter, for a total consolidation period of at least 12 weeks. Secondary prophylaxis with fluconazole (200 mg per day) was then continued for at least 1 year. ART regimens, which were selected before randomization, consisted of either zidovudine or stavudine, each with lamivudine and efavirenz. Tenofovir was avoided as an initial ART medication because of concern about potential nephrotoxicity with concomitant amphotericin treatment.

The President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) provided support for HIV care but not for research. ART was provided by PEPFAR in Uganda and by the Department of Health in South Africa. Merck Sharp & Dohme donated a reserve supply of efavirenz but did not have any other involvement in any aspect of the trial.

Randomization and Follow-up

We used a computer-generated, permuted-block randomization algorithm with blocks of different sizes in a 1:1 ratio, stratified according to site and the presence or absence of altered mental status at the time that informed consent was obtained (Glasgow Coma Scale score ≤14 vs. 15; scores can range from 3 to 15, with lower scores indicating reduced levels of consciousness). Sequentially numbered, opaque, sealed envelopes stored in a lockbox contained the randomization assignments for enrolled participants. Envelopes were opened after written informed consent had been obtained.

After the initial diagnostic lumbar puncture, therapeutic lumbar punctures were performed, with the use of manometers, on day 7 and day 14 of amphotericin therapy and additionally as needed for the control of intracranial pressure (a median of three lumbar punctures). Routine care included the administration of intravenous fluids (≥2 liters per day), electrolyte management, and trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole prophylaxis. Participants were followed daily while hospitalized, then every 2 weeks for 12 weeks and monthly thereafter through 46 weeks. For details of study conduct, see the protocol and statistical analysis plan, available with the full text of this article at NEJM.org.

Study End Points

The primary end point was survival at 26 weeks. (The results of the primary analysis are expressed in the text as mortality at 26 weeks.) The secondary end points were survival through 46 weeks, cryptococcal IRIS, relapse of cryptococcal meningitis, fungal clearance, virologic suppression (<400 copies per milliliter) at 26 weeks, adverse events (grades 3 to 5), and ART discontinuation for more than 3 days for any reason. Cryptococcal IRIS was defined in accordance with the published case definition.24 An external panel of three physicians who were not aware of ART timing adjudicated IRIS events and deaths. Relapse of cryptococcal meningitis was defined as recurrence of symptoms and increasing growth of cryptococcus in CSF quantitative culture after 4 weeks of treatment. Fungal clearance was assessed with the use of the early fungicidal activity method.25 Adverse events were classified according to the 2009 Division of AIDS toxicity scale.

Interim Monitoring

The National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases data and safety monitoring board for African studies reviewed interim analyses annually. A Lan–DeMets spending-function analogue of the O’Brien–Fleming boundaries was proposed to control the type I error resulting from multiple interim analyses. After the second review in April 2012, the data and safety monitoring board recommended stopping enrollment because of substantial excess mortality with earlier ART. Enrollment was stopped on April 27, 2012, with 177 participants enrolled.

Statistical Analysis

We compared the primary end point (survival at 26 weeks) in the treatment groups using time-to-event methods with Cox proportional-hazards models. The study was statistically powered to detect a 25% relative survival benefit (absolute benefit, 15 percentage points) with 90% power and an overall two-sided alpha level of 0.05 with an intended sample size of 500 participants. The a priori assumption was that the survival rate at 26 weeks would be 40 to 50% with the deferred-ART strategy.19,26–30 Survival at 26 weeks was compared among prespecified subgroups defined according to baseline characteristics, with the use of models including an interaction term between treatment group and subgroup.

Categorical secondary end points were compared with the use of Fisher’s exact test. To account for the competing risk of death, the cumulative incidence function was used to compare the end points of IRIS, relapse, and adverse events between treatment groups.31 A linear mixed-effects regression model fit with a random intercept and slope was used to estimate the rate of fungal clearance, measured as the log10 decrease in colony-forming units (CFU) of cryptococcus per milliliter of CSF per day among all participants for whom two or more cultures were available.22 All analyses were conducted with SAS software version 9.3 (SAS Institute), according to the intention-to-treat principle, on the basis of a two-sided type I error with an alpha level of 0.05.

Results

Participants

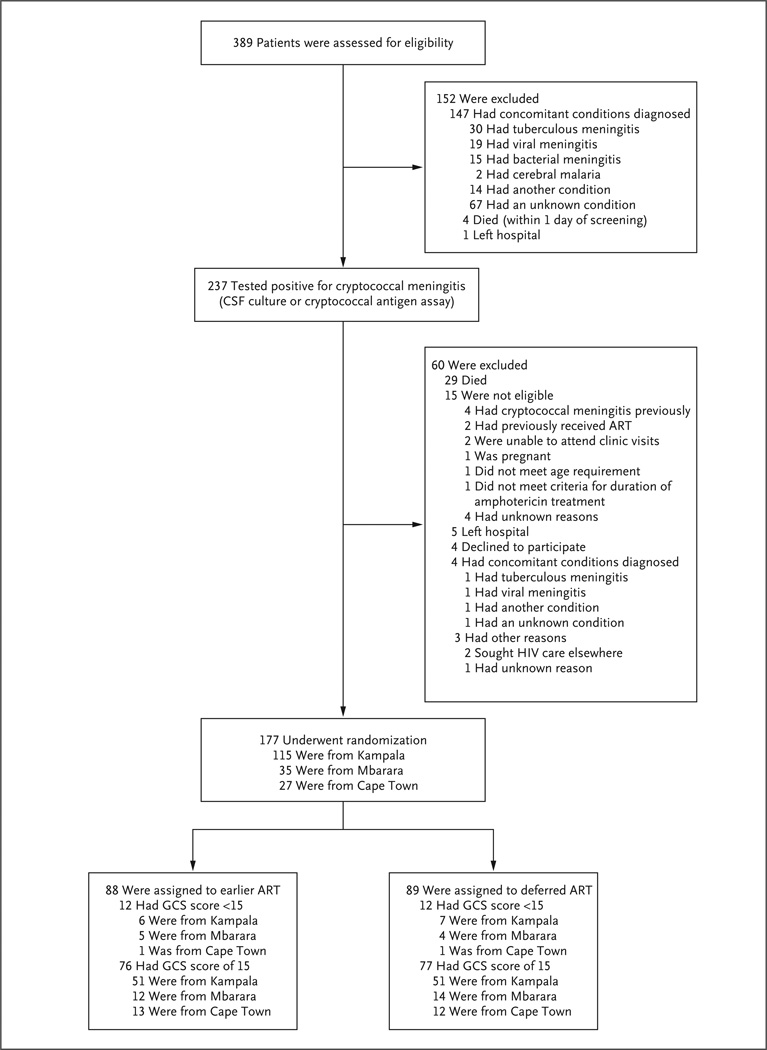

Among the 389 patients with suspected meningitis who were screened, 177 with cryptococcal meningitis were randomly assigned to a treatment group after a median of 8 days of amphotericin therapy (interquartile range, 7 to 8) (Fig. 1). The demographic and baseline clinical characteristics of the study participants were typical of those for patients with cryptococcal meningitis and did not differ significantly between treatment groups (Table 1). Linkage to outpatient care occurred for 99% of participants, 94% missed one or no study visits, and vital status at 46 weeks was known for all 177 participants except 1, who withdrew consent. The total follow-up time was 100.7 person-years.

Figure 1. Screening and Randomization.

Of 237 patients with cryptococcal meningitis, 177 were enrolled in the study after 7 to 11 days of antifungal treatment. One participant randomly assigned to receive earlier antiretroviral therapy (ART) withdrew consent 2 days after randomization. All other participants were followed for 46 weeks or until death. No participants were lost to follow-up. Analyses were performed according to the intention-to-treat principle. Randomization was stratified according to site and the presence or absence of altered mental status (Glasgow Coma Scale [GCS] score <15) at the time informed consent was obtained (within 48 hours before randomization).

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics According to Treatment Group.*

| Characteristic | Earlier ART (N = 88) |

Deferred ART (N = 89) |

|---|---|---|

| Median age (IQR) — yr | 35 (28–40) | 36 (30–40) |

| Male sex — no. (%) | 46 (52) | 47 (53) |

| Median weight (IQR) — kg† | 53.0 (46.5–58.8) | 54.1 (48.3–59.0) |

| Glasgow Coma Scale score at screening — no. (%) | ||

| 15 | 67 (76) | 62 (70) |

| 14 | 13 (15) | 14 (16) |

| 11–13 | 6 (7) | 7 (8) |

| ≤10 | 2 (2) | 6 (7) |

| Median duration of headache (IQR) — days | 14 (7–28) | 14 (7–25) |

| CSF characteristics at diagnosis‡ | ||

| Median opening pressure (IQR) — mm H2O | 280 (190–360) | 260 (180–410) |

| Opening pressure >250 mm H2O — no./total no. (%) | 46/79 (58) | 38/74 (51) |

| Median quantitative culture result (IQR) — log10CFU/ml | 5.3 (4.2–5.7) | 4.8 (3.8–5.5) |

| Median cryptococcal antigen titer (IQR)§ | 1:8000 (1:2000–1:16,000) | 1:4000 (1:1000–1:14,400) |

| Median white-cell count (IQR) — cells/mm3 | 9 (4–85) | 25 (4–110) |

| White-cell count <5 cells/mm3— no./total no. (%) | 36/80 (45) | 27/83 (33) |

| Median protein level (IQR) — mg/dl | 99 (46–185) | 106 (61–181) |

| CSF characteristics at randomization¶ | ||

| Median opening pressure (IQR) — mm H2O | 220 (120–300) | 200 (124–300) |

| Opening pressure >250 mm H2O — no./total no. (%) | 26/71 (37) | 25/65 (38) |

| Median quantitative culture result (IQR) — log10CFU/ml | 2.5 (0.2–4.0) | 2.3 (0.0–3.4) |

| Median white-cell count (IQR) — cells/mm3 | 13 (4–96) | 18 (4–80) |

| White-cell count <5 cells/mm3— no./total no. (%) | 33/75 (44) | 31/71 (44) |

| Median protein level (IQR) — mg/dl | 105 (50–196) | 95 (70–148) |

| No lumbar puncture performed — no. (%) | 9 (10) | 8 (9) |

| Active tuberculosis — no. (%) | ||

| None | 64 (73) | 67 (75) |

| Previous, completed treatment | 7 (8) | 7 (8) |

| Current, receiving an induction regimen | 14 (16) | 10 (11) |

| Current, receiving a 2-drug consolidation regimen | 3 (3) | 5 (6) |

| Previous AIDS-related opportunistic infection — no. (%) | 7 (8) | 7 (8) |

| Median hemoglobin level (IQR) — g/dl | ||

| At diagnosis of cryptococcal meningitis | 11.0 (8.9–12.7) | 11.5 (9.3–13.2) |

| At randomization | 9.2 (7.6–10.9) | 8.9 (7.6–10.3) |

| Median CD4 cell count (IQR) — cells/mm3 | 19 (9–69) | 28 (11–76) |

| Median HIV RNA level (IQR) — log10 copies/ml | 5.5 (5.2–5.8) | 5.5 (5.3–5.8) |

ART denotes antiretroviral therapy, CFU colony-forming units, CSF cerebrospinal fluid, and IQR interquartile range. P values (based on the chi-square or Wilcoxon test) were greater than 0.10 for all between-group comparisons.

Data on weight were unavailable for 13 participants in the earlier-ART group and 11 in the deferred-ART group, who were too severely ill to stand.

Quantitative culture data were not available for 4 participants in the earlier-ART group and 2 participants in the deferred-ART group, because their first lumbar puncture was performed at an outside facility. Opening CSF pressure was not measured in 9 participants in the earlier-ART group and 15 participants in the deferred-ART group, because their initial lumbar puncture was performed by physicians not involved in the study.

Titers were determined with the use of a lateral flow assay.

Data were collected during the period from day 7 to day 11 of amphotericin therapy (median, day 8) and before randomization and were available for 75 participants in the earlier-ART group and 71 participants in the deferred-ART group.

The median times from diagnosis of cryptococcal meningitis to ART initiation were 9 days (interquartile range, 8 to 9) in the earlier-ART group and 36 days (interquartile range, 34 to 38) in the deferred-ART group. In the earlier-ART group, 1 participant died after randomization but before the initiation of ART, and 1 started to receive ART but withdrew consent 2 days after randomization (both were included in the intention-to-treat analysis). In the deferred-ART group, 18 participants (20%) died after randomization and before the ART-initiation window closed (42 days) and never received ART, 1 participant with Kaposi’s sarcoma started to receive ART 5 days before the 4-week window opened, for clinical reasons, 62 participants (70%) started within their assigned window, 6 participants (7%) started to receive ART after 42 days, and 2 participants (2%) died after 42 days without receiving ART. The initial ART regimens were zidovudine, lamivudine, and efavirenz in 80% of participants; stavudine, lamivudine, and efavirenz in 19%; and tenofovir, lamivudine, and efavirenz in 1%. Switches to a second ART regimen occurred in 46% of participants (72 of 156); in 52 patients, the switch was to tenofovir. Participants initially receiving stavudine were systematically switched to tenofovir at 12 weeks.

Primary End Point

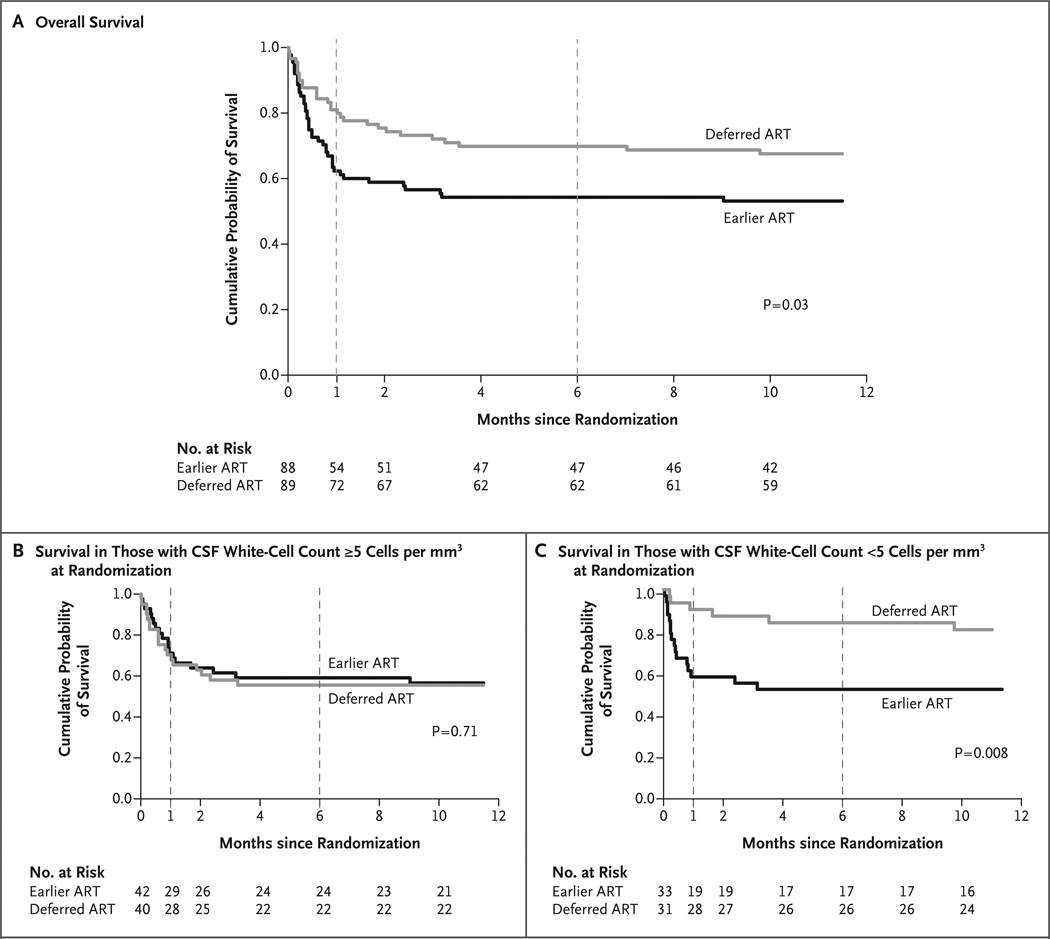

The proportion of participants who died by 26 weeks was greater in the earlier-ART group than in the deferred-ART group (40 of 88 [45%] vs. 27 of 89 [30%]; hazard ratio for death, 1.73; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.06 to 2.82; P = 0.03) (Fig. 2). The difference in mortality between the two groups occurred early during treatment, during study days 8 through 30 (2 to 5 weeks after diagnosis), when participants were receiving consolidation fluconazole therapy (800 mg per day). During this period, 21 of 75 participants (28%) in the earlier-ART group and 8 of 80 (10%) in the deferred-ART group died (hazard ratio, 3.10; 95% CI, 1.37 to 7.00; P = 0.007). Mortality did not differ significantly thereafter (P = 0.87). Between weeks 26 and 46, 1 participant randomly assigned to the earlier-ART group and 2 participants randomly assigned to the deferred-ART group died (overall hazard ratio at 46 weeks, 1.66; 95% CI, 1.03 to 2.68; P = 0.04).

Figure 2. Cumulative Probability of Survival According to Timing of ART.

Overall survival from randomization (time 0) at 7 to 11 days after diagnosis of cryptococcal meningitis to 46 weeks is shown in Panel A. Earlier ART initiation, at 7 to 13 days after diagnosis, was associated with a risk of death within 26 weeks that was 15 percentage points higher than that associated with ART initiation at 5 weeks after diagnosis (P = 0.03). Panels B and C show survival stratified according to the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) white-cell count at the time of randomization. Among study participants with a paucity of CSF white cells (<5 cells per cubic millimeter), mortality was significantly higher with earlier ART initiation than with deferred ART initiation (P = 0.008). In all panels, the vertical dashed line at 1 month indicates the time of ART initiation in the deferred-ART group. The primary outcome was the survival at 26 weeks (vertical dashed line at 6 months).

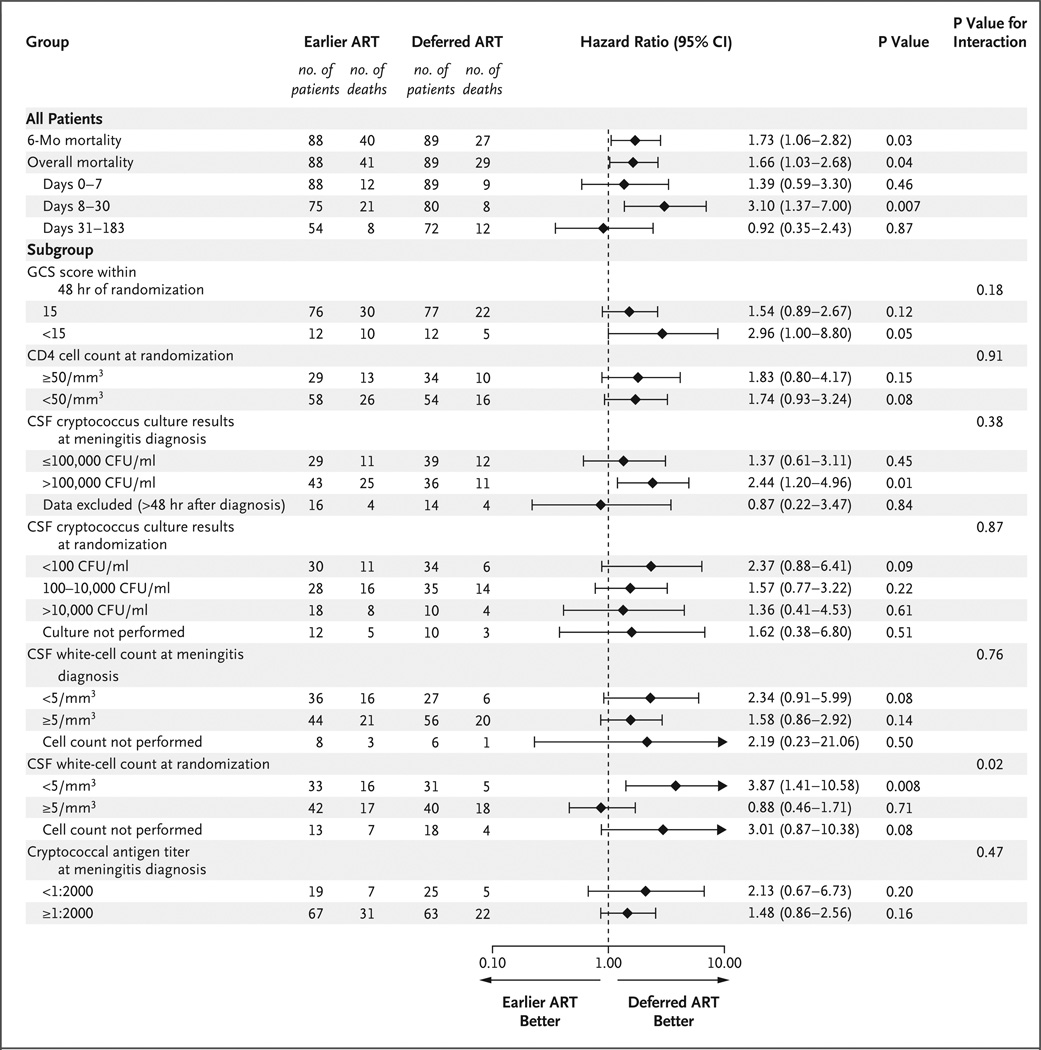

Subgroup Analyses

We assessed prespecified subgroups to determine whether differences in survival between treatment groups at 26 weeks were dependent on participants’ baseline clinical characteristics (Fig. 3). The only characteristic with a significant interaction was the white-cell count in CSF at randomization (P = 0.02 for interaction) (Fig. 2B, 2C, and 3). For the subgroup with a CSF white-cell count of less than 5 cells per cubic millimeter, mortality was higher with earlier ART than with deferred ART (hazard ratio, 3.87; 95% CI, 1.41 to 10.58; P = 0.008). In contrast, the survival rate was similar between treatment groups in the subgroup with CSF white-cell counts of 5 cells per cubic millimeter or higher at randomization (hazard ratio, 0.88; 95% CI, 0.46 to 1.71; P = 0.71). Earlier ART was not favorable in any subgroup analyzed, including participants at high risk for death, such as those with CD4 cell counts of less than 50 per cubic millimeter (hazard ratio, 1.74; 95% CI, 0.93 to 3.24) and those with an altered mental status (Glasgow Coma Scale score <15) at randomization (hazard ratio, 2.96; 95% CI, 1.00 to 8.80). Participants at lower risk for death, such as those with a lower CSF fungal burden at day 7 of antifungal therapy, also did not benefit from earlier ART.

Figure 3. Subgroup Analyses of Mortality.

Prespecified subgroups were assessed to determine whether differences in survival between treatment groups at 26 weeks were dependent on baseline clinical characteristics. Values for subgroups are 6-month mortality. The CSF white-cell count at randomization was the only characteristic with a significant interaction, which suggested a differential response to the timing of ART initiation.

Secondary End Points

The timing of ART initiation did not influence any of the secondary end points (Table 2). Even the cumulative incidence of recognized cryptococcal IRIS did not differ significantly between the earlier-ART group and the deferred-ART group (20% [17 of 87] and 13% [9 of 69], respectively; P = 0.32) (Fig. S1 in the Supplementary Appendix, available at NEJM.org). As expected, CD4 cell counts and virologic responses differed during the first month after randomization (with and without ART), but values converged by 26 weeks (Fig. S2 in the Supplementary Appendix). Earlier ART did not increase the rate of cryptococcal clearance in CSF; early fungicidal activity was −0.31 CFU per milliliter per day in both treatment groups (95% CI, −0.33 to −0.28; 166 participants), with similar rates of CSF culture positivity at 14 days (37% in the earlier-ART group and 39% in the deferred-ART group, P = 0.87). Among 59 participants with positive CSF cultures at 14 days, the median cryptococcal growth was 100 CFU per milliliter (interquartile range, 15 to 500), with no significant difference between treatment groups (P = 0.13); only 5 participants had more than 10,000 CFU per milliliter in CSF. Adverse events were frequent and primarily attributable to amphotericin, and the rates did not differ significantly between the treatment groups (Fig. S3 and Table S1 in the Supplementary Appendix). Thus, earlier ART initiation did not have any advantages over deferred ART initiation with respect to secondary end points.

Table 2.

Secondary Outcomes in the Two Treatment Groups.*

| Outcome | Earlier ART | Deferred ART | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of Patients |

C No. of Events |

cumulative Incidence (95% CI) |

No. of Patients |

No. of Events |

Cumulative Incidence (95% CI) |

P Value | |

| percent | percent | ||||||

| Cryptococcal IRIS† | 87 | 17 | 20 (12–29) | 69 | 9 | 13 (6–22) | 0.32 |

| CSF culture positive at 14 days of amphotericin therapy‡ | 76 | 28 | 37 (26–49) | 80 | 31 | 39 (28–50) | 0.87 |

| Cryptococcal meningitis relapse§ | 88 | 2 | 2 (<1–7) | 89 | 8 | 9 (4–16) | 0.06 |

| Adverse events¶ | |||||||

| Grade 3–5 | 88 | 73 | 84 (74–90) | 89 | 75 | 84 (75–91) | 0.98 |

| Grade 4 or 5 | 88 | 49 | 56 (45–66) | 89 | 47 | 53 (42–63) | 0.64 |

| ART discontinuation for ≥3 days | 87 | 5 | 6 (2–13) | 69 | 1 | 1 (0–8) | 0.23 |

| Plasma HIV RNA level <400 copies/ml at 26 wk | 47 | 43 | 91 (80–98) | 59 | 49 | 83 (71–92) | 0.26 |

The cumulative incidence of immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome (IRIS), relapse, and adverse events and associated P values were calculated with Gray's method to account for the competing risk of death.31 Other percentages and associated P values were calculated with exact methods for binomial proportions.

IRIS events among patients who received ART are included. The presence of IRIS was determined by an external adjudication panel on the basis of the consensus case definition for cryptococcal IRIS.24

Data for day 14 lumbar puncture were missing for 18 participants in the earlier-ART group: 12 who died, 1 who withdrew consent, and 5 who declined to undergo lumbar puncture. Data were missing for 12 participants in the deferred-ART group: 6 who died and 6 who declined to undergo lumbar puncture. Results of CSF cultures that were sterile before day 14 were carried forward if a quantitative culture was not available at day 14.

Cryptococcal relapse was defined as recurrence of symptoms and increasing cryptococcal growth in CSF quantitative culture after 4 weeks.

Grade 5 events (deaths) were not related to cryptococcal meningitis. Adverse events were defined in accordance with the 2009 version of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Division of AIDS classification scale.

Causes of Death

The causes of death were similar in the two treatment groups, with the exception of an excess of cryptococcal meningitis–related deaths in the earlier-ART group (19, vs. 10 deaths in the deferred-ART group). The other causes of death in the earlier-ART group and deferred-ART group, respectively, were bacterial sepsis (9 and 7 deaths), tuberculosis-related causes (2 and 2), IRIS-related causes (1 and 2), cryptococcal meningitis relapse (0 and 2), adverse events due to medication (2 and 0), pulmonary embolism (2 and 2), hypokalemia or hypovolemia (0 and 1), and unknown causes (2 and 3); causes of death reported only in the earlier-ART group were toxoplasmosis (1), intracranial pressure (1), head trauma (1), and multifactorial causes (1). Twenty-seven postmortem examinations were performed (for 39% of deaths), and external adjudication was in agreement with 88% of clinician-ascertained cryptococcal meningitis– related causes of death, with disagreements reconciled after review of additional clinical and postmortem data.

Thirteen cryptococcal meningitis–related deaths occurred between 2 and 5 weeks after diagnosis (10 in the earlier-ART group and 3 in the deferred-ART group) and were judged to be caused by the initial cryptococcosis rather than separate, distinct cryptococcal-IRIS events. Of the 10 patients who died from cryptococcal meningitis–related causes in the earlier-ART group between 2 and 5 weeks after diagnosis, 5 had CSF opening pressures below 250 mm of water at their last lumbar puncture, and 7 had decreases greater than 3 log10 CFU of cryptococcus per milliliter in their CSF cultures. Thus, clinically it is unclear whether these excess deaths in the earlier-ART group were directly due to sequelae of cryptococcal meningitis or due to IRIS.

CSF White-Cell Count

Earlier ART did have a detectable effect on the immune response in CSF. At day 14 of amphotericin treatment, the proportion of participants who had CSF white-cell counts of 5 per cubic millimeter or higher was greater with earlier initiation of ART (median, 6 days of ART) than with deferred initiation (58% vs. 40%, P = 0.047). The difference was accounted for by an influx of CSF white cells in 10 of the 23 participants (43%) in the earlier-ART group who did not have CSF pleocytosis at diagnosis, as compared with none of the 20 participants without pleocytosis in the deferred-ART group, who were not yet receiving ART (P = 0.001). With earlier ART, it was difficult to determine whether deterioration early after randomization was due to cryptococcal IRIS or to progressive sequelae of cryptococcal meningitis. Nevertheless, earlier ART initiation was associated with significant excess mortality.

Discussion

This multisite randomized trial showed that deferring ART until 5 weeks after the start of amphotericin therapy improved survival rates among patients with cryptococcal meningitis, as compared with initiating ART at 1 to 2 weeks. This improved survival associated with deferring ART was observed in patients with advanced HIV infection, including patients with severe disease, such as those with CD4 cell counts of less than 50 per cubic millimeter, altered mental status, or lack of CSF pleocytosis. The higher short-term mortality observed with earlier ART initiation in this trial may relate to the site of infection in the anatomically constrained CNS.

This adverse effect of earlier ART after cryptococcosis may involve unrecognized increases in inflammatory responses in the CNS due to ART-associated immune reconstitution in the first month after ART initiation. Earlier ART also does not appear to be beneficial in the treatment of HIV-associated tuberculous meningitis.26 In contrast to these meningitis results, earlier ART has been shown to reduce AIDS-defining events and deaths in a group of patients with various opportunistic infections,13 as well as among persons with noncerebral tuberculosis who had CD4 cell counts of less than 50 per cubic millimeter.10,11 Thus, the outcomes and consequences of CNS infections, such as cryptococcal and tuberculous meningitis, differ from those of other AIDS-related opportunistic infections, in that earlier ART can be detrimental in CNS infections14,17 but can be beneficial overall in non-CNS opportunistic infections.16

We observed the highest risk of death with earlier ART among participants with low numbers of CSF white cells at randomization. A paucity of CSF white cells has previously been reported as a significant risk factor for cryptococcal IRIS.32,33 In tuberculosis, earlier ART is associated with a risk of IRIS that is three to six times as high as the risk associated with deferred ART10–12,34; however, unlike cryptococcal IRIS, tuberculosis IRIS outside the CNS is rarely fatal.35,36 Therefore, we hypothesize that earlier ART is most harmful in high-risk persons with a predisposition to cryptococcal IRIS (i.e., those without CSF inflammation) and that this effect drove the overall results of our trial. IRIS with CNS infections initiates local inflammation in a confined space, within intracranial structures that are permissive neither to inflammation nor to compression.17,19,37 Persons who have not fully recovered from their initial meningitis episode may not survive a second insult due to IRIS. A limitation of the IRIS case definition is the requirement for previous clinical improvement.24 For the earlier-ART group, clinicians and the adjudication committee were often unable to discern whether progressive clinical deterioration was due to complications of cryptococcosis or to cryptococcal IRIS, which probably resulted in an ascertainment bias, with underdetection of early IRIS events. Conversely, the cryptococcal IRIS case definition performed well for later IRIS events, in scenarios in which patients had clinical improvement, started to receive ART, and then had clinical deterioration.

The differences in mortality between the two treatment groups were of sufficient magnitude that the trial was stopped early by the data and safety monitoring board. As a result, the treatment groups in the COAT Trial did not reach the proposed cohort size. Historically, trials stopped early have routinely overestimated the magnitude of benefit or harm.38,39 Moreover, the smaller sample limits the power for subgroup analyses to provide customized guidance for care of individual patients. This limitation is particularly notable for study participants with CSF pleocytosis, for whom definitive guidance on ART initiation was not determined; however, earlier ART was not beneficial in our analysis. Nevertheless, we believe the main finding of this multisite treatment-strategy trial is generalizable to affected persons in resource-limited and high-income countries. COAT Trial participants received a high level of care from experienced clinicians.20,21 Persons presenting with suspected meningitis underwent lumbar puncture promptly, and comprehensive CSF diagnostic tests were performed with standardized checklists.2 Intracranial pressure was monitored routinely, and elevated pressure was managed with a median of three therapeutic lumbar punctures during hospitalization. A strength of the trial was the extensive inpatient HIV counseling with systematic linkage to outpatient care; 99% of patients were retained in care as outpatients. The survival rate in both treatment groups was improved as compared with our historical prospective experience with the use of amphotericin and the same deferred-ART regimens (6-month survival rate, 40 to 50%).19,26–29,40 Indeed, the improved outcomes in this trial suggest that increased survival is possible in resource-limited settings.20 However, earlier ART initiation during hospitalization does not improve survival.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Supported by grants from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID; U01AI089244, K23AI073192, T32AI055433, and K24AI096925), the Wellcome Trust (081667 and 098316, to Dr. Meintjes, and 087540, to Dr. Meya), and the Veterans Affairs Research Service (to Dr. Janoff ).

We thank Dr. Trinh Ly, Dr. Chris Lambros, Karen Reese, and Dr. Neal Wetherall for their support; Drs. Tihana Bicanic, Lewis Haddow, and Jason Baker for serving on the external adjudication committee; Professors Jim Neaton, Thomas Harrison, John Perfect, and Philippa Easterbrook for providing input on study design and clinical care; Drs. Alex Coutinho, Aaron Friedman, Moses Kamya, and Robert J. Wilkinson for providing institutional support; Dr. Anne Marie Weber-Main for critical review of a previous draft of the manuscript; the Infectious Disease Institute DataFax team of Mariam Namawejje and Mark Ssennono for data management with support from Kevin Newell, Steven Reynolds, and the staff of the NIAID Office of Cyberinfrastructure and Computational Biology; and the clinical and administrative staff of the Provincial Government of the Western Cape of South Africa for their support.

Footnotes

A list of members of the Cryptococcal Optimal ART Timing (COAT) Trial Team is provided in the Supplementary Appendix, available at NEJM.org

References

- 1.Jarvis JN, Meintjes G, Williams A, Brown Y, Crede T, Harrison TS. Adult meningitis in a setting of high HIV and TB prevalence: findings from 4961 suspected cases. BMC Infect Dis. 2010;10:67. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-10-67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Durski KN, Kuntz KM, Yasukawa K, Virnig BA, Meya DB, Boulware DR. Cost-effective diagnostic checklists for meningitis in resource-limited settings. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2013;63(3):e101–e108. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31828e1e56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cohen DB, Zijlstra EE, Mukaka M, et al. Diagnosis of cryptococcal and tuberculous meningitis in a resource-limited African setting. Trop Med Int Health. 2010;15:910–917. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2010.02565.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Group for Enteric, Respiratory and Meningeal Disease Surveillance in South Africa. GERMS-SA annual report. Johannesburg: National Institute for Communicable Diseases; http://www.nicd.ac.za/assets/files/GERMS-SA%202012%20Annual %20Report.pdf) [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hakim JG, Gangaidzo IT, Heyderman RS, et al. Impact of HIV infection on meningitis in Harare, Zimbabwe: a prospective study of 406 predominantly adult patients. AIDS. 2000;14:1401–1407. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200007070-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Park BJ, Wannemuehler KA, Marston BJ, Govender N, Pappas PG, Chiller TM. Estimation of the current global burden of cryptococcal meningitis among persons living with HIV/AIDS. AIDS. 2009;23:525–530. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328322ffac. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.French N, Gray K, Watera C, et al. Cryptococcal infection in a cohort of HIV-1-infected Ugandan adults. AIDS. 2002;16:1031–1038. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200205030-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liechty CA, Solberg P, Were W, et al. Asymptomatic serum cryptococcal antigenemia and early mortality during antiretroviral therapy in rural Uganda. Trop Med Int Health. 2007;12:929–935. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2007.01874.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lawn SD, Harries AD, Anglaret X, Myer L, Wood R. Early mortality among adults accessing antiretroviral treatment programmes in sub-Saharan Africa. AIDS. 2008;22:1897–1908. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32830007cd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blanc FX, Sok T, Laureillard D, et al. Earlier versus later start of antiretroviral therapy in HIV-infected adults with tuberculosis. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:1471–1481. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1013911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Havlir DV, Kendall MA, Ive P, et al. Timing of antiretroviral therapy for HIV-1 infection and tuberculosis. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:1482–1491. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1013607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Abdool! Karim SS, Naidoo K, Grobler A, et al. Integration of antiretroviral therapy with tuberculosis treatment. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:1492–501. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1014181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zolopa A, Andersen J, Powderly W, et al. Early antiretroviral therapy reduces AIDS progression/death in individuals with acute opportunistic infections: a multi-center randomized strategy trial. PLoS One. 2009;4(5):e5575. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Makadzange AT, Ndhlovu CE, Takarinda K, et al. Early versus delayed initiation of antiretroviral therapy for concurrent HIV infection and cryptococcal meningitis in sub-Saharan Africa. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50:1532–1538. doi: 10.1086/652652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bisson GP, Molefi M, Bellamy S, et al. Early versus delayed antiretroviral therapy and cerebrospinal fluid fungal clearance in adults with HIV and cryptococcal meningitis. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;57:1165–1173. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit019. [Erratum, Clin Infect Dis:p1067.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grant PM, Zolopa AR. When to start ART in the setting of acute AIDS-related opportunistic infections: the time is now! Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2012;9:251–258. doi: 10.1007/s11904-012-0126-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Török ME, Yen NT, Chau TT, et al. Timing of initiation of antiretroviral therapy in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)–associated tuberculous meningitis. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52:1374–1383. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bahr N, Boulware DR, Marais S, Scriven J, Wilkinson RJ, Meintjes G. Central nervous system immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2013;15:583–593. doi: 10.1007/s11908-013-0378-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Boulware DR, Meya DB, Bergemann TL, et al. Clinical features and serum bio-markers in HIV immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome after cryptococ-cal meningitis: a prospective cohort study. PLoS Med. 2010;7(12):e1000384. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rapid advice: diagnosis, prevention and management of cryptococcal disease in HIV-infected adults, adolescents and children. Geneva: World Health Organization; http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2011/9789241502979_eng.pdf. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Perfect JR, Dismukes WE, Dromer F, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of cryptococcal disease: 2010 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50:291–322. doi: 10.1086/649858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Day JN, Chau TT, Wolbers M, et al. Combination antifungal therapy for cryptococcal meningitis. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:1291–1302. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1110404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Loyse A, Thangaraj H, Easterbrook P, et al. Cryptococcal meningitis: improving access to essential antifungal medicines in resource-poor countries. Lancet Infect Dis. 2013;13:629–637. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70078-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Haddow LJ, Colebunders R, Meintjes G, et al. Cryptococcal immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome in HIV-1-infected individuals: proposed clinical case definitions. Lancet Infect Dis. 2010;10:791–802. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(10)70170-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bicanic T, Muzoora C, Brouwer AE, et al. Independent association between rate of clearance of infection and clinical outcome of HIV-associated cryptococcal meningitis: analysis of a combined cohort of 262 patients. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49:702–709. doi: 10.1086/604716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kambugu A, Meya DB, Rhein J, et al. Outcomes of cryptococcal meningitis in Uganda before and after the availability of highly active antiretroviral therapy. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46:1694–1701. doi: 10.1086/587667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Butler EK, Boulware DR, Bohjanen PR, Meya DB. Long term 5-year survival of persons with cryptococcal meningitis or asymptomatic subclinical antigenemia in Uganda. PLoS One. 2012;7(12):e51291. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0051291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Muzoora CK, Kabanda T, Ortu G, et al. Short course amphotericin B with high dose fluconazole for HIV-associated cryptococcal meningitis. J Infect. 2012;64:76–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2011.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bicanic T, Meintjes G, Wood R, et al. Fungal burden, early fungicidal activity, and outcome in cryptococcal meningitis in anti-retroviralnaive or antiretroviral-experienced patients treated with amphotericin B or fluconazole. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45:76–80. doi: 10.1086/518607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Longley N, Muzoora C, Taseera K, et al. Dose response effect of high-dose fluconazole for HIV-associated cryptococcal meningitis in southwestern Uganda. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;47:1556–1561. doi: 10.1086/593194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gray RJ. A class of K-sample tests for comparing the cumulative incidence of a competing risk. Ann Stat. 1998;16:1141–1154. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Boulware DR, Bonham SC, Meya DB, et al. Paucity of initial cerebrospinal fluid inflammation in cryptococcal meningitis is associated with subsequent immune re-constitution inflammatory syndrome. J Infect Dis. 2010;202:962–970. doi: 10.1086/655785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chang CC, Dorasamy AA, Gosnell BI, et al. Clinical and mycological predictors of cryptococcosis-associated immune re-constitution inflammatory syndrome. AIDS. 2013;27:2089–2099. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3283614a8d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lawn SD, Myer L, Bekker LG, Wood R. Tuberculosis-associated immune reconstitution disease: incidence, risk factors and impact in an antiretroviral treatment service in South Africa. AIDS. 2007;21:335–341. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328011efac. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Meintjes G, Wilkinson RJ, Morroni C, et al. Randomized placebo-controlled trial of prednisone for paradoxical tuberculosis-associated immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome. AIDS. 2010;24:2381–2390. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32833dfc68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Worodria W, Massinga-Loembe M, Mazakpwe D, et al. Incidence and predictors of mortality and the effect of tuberculosis immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome in a cohort of TB/HIV patients commencing antiretroviral therapy. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2011;58:32–37. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3182255dc2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lawn SD, Bekker LG, Myer L, Orrell C, Wood R. Cryptococcocal immune reconstitution disease: a major cause of early mortality in a South African antiretroviral programme. AIDS. 2005;19:2050–2052. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000191232.16111.f9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bassler D, Briel M, Montori VM, et al. Stopping randomized trials early for benefit and estimation of treatment effects: systematic review and meta-regression analysis. JAMA. 2010;303:1180–1187. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pocock SJ. When (not) to stop a clinical trial for benefit. JAMA. 2005;294:2228–2230. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.17.2228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bicanic T, Meintjes G, Rebe K, et al. Immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome in HIV-associated cryptococcal meningitis: a prospective study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2009;51:130–134. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181a56f2e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.