Abstract

The skin has a dual function as a barrier and a sensory interface between the body and the environment. To protect against invading pathogens, the skin harbors specialized immune cells, including dermal dendritic cells (DDCs) and interleukin (IL)-17 producing γδ T cells (γδT17), whose aberrant activation by IL-23 can provoke psoriasis-like inflammation1–4. The skin is also innervated by a meshwork of peripheral nerves consisting of relatively sparse autonomic and abundant sensory fibers. Interactions between the autonomic nervous system and immune cells in lymphoid organs are known to contribute to systemic immunity, but how peripheral nerves regulate cutaneous immune responses remains unclear5,6. Here, we have exposed the skin of mice to imiquimod (IMQ), which induces IL-23 dependent psoriasis-like inflammation7,8. We show that a subset of sensory neurons expressing the ion channels TRPV1 and NaV1.8 is essential to drive this inflammatory response. Imaging of intact skin revealed that a large fraction of DDCs, the principal source of IL-23, is in close contact with these nociceptors. Upon selective pharmacological or genetic ablation of nociceptors9–11, DDCs failed to produce IL-23 in IMQ exposed skin. Consequently, the local production of IL-23 dependent inflammatory cytokines by dermal γδT17 cells and the subsequent recruitment of inflammatory cells to the skin were dramatically reduced. Intradermal injection of IL-23 bypassed the requirement for nociceptor communication with DDCs and restored the inflammatory response12. These findings indicate that TRPV1+NaV1.8+ nociceptors, by interacting with DDCs, regulate the IL-23/IL-17 pathway and control cutaneous immune responses.

Repeated topical application of imiquimod (IMQ) to murine skin provokes inflammatory lesions that resemble human psoriasis7,8. This response is mediated by IL-23, which stimulates skin-resident γδ T cells to secrete IL-17 and IL-22, cytokines that induce inflammatory leukocyte recruitment and acanthosis13. Indeed, antibodies targeting the shared p40 subunit of IL-12 and IL-23 inhibit both IMQ-induced murine dermatitis and human psoriasis8,13. Frequent symptoms in human psoriasis, aside from the prominent skin lesions, include the sensations of itch, pain and discomfort in affected areas14. Clinical reports suggest that intralesionally administered anesthetics or surgical denervation of psoriatic lesions not only abrogate local sensation, but also ameliorate local inflammation15. Similarly, in mutant mice with disseminated psoriasiform dermatitis, peripheral nerve dissection attenuated skin inflammation16; however, cutaneous nerves are composed of sympathetic and several types of sensory fibers, and the role of individual types of nerve fibers remains unclear6. Here, using the IMQ-model, we have investigated whether and how specific subsets of peripheral nerves contribute to the formation of psoriasiform skin lesions.

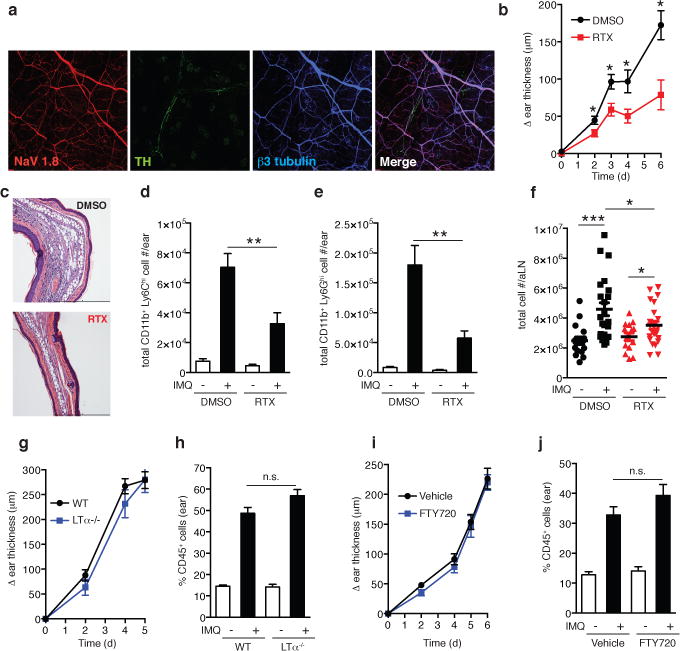

Skin sensations perceived as inflammatory pain, noxious heat and some forms of itch are transmitted by sensory fibers that express the cation channel TRPV1. Most TRPV1+ fibers co-express the sodium channel NaV1.8 (ref. 9–11). NaV1.8+nociceptors can be identified in the dermis of NaV1.8-TdTomato (TdT) mice by their red fluorescence (Fig. 1a)9. Confocal microscopy of skin samples from NaV1.8-TdT mice co-stained for tyrosine hydroxylase (TH), which identifies sympathetic fibers, and for β3-tubulin, a pan-neuronal marker, revealed that NaV1.8+TH− nociceptors represent the vast majority of cutaneous nerve fibers, while NaV1.8−TH+ sympathetic fibers are rare.

Figure 1. TRPV1+ nociceptor ablation attenuates skin inflammation and draining lymph node hypertrophy in the IMQ model.

a, Representative whole-mount confocal micrograph of normal ear skin from NaV1.8-TdT reporter mice (NaV1.8+ nociceptors, red) stained for β3-tubulin (peripheral nerves, blue) and tyrosine hydroxylase (TH, sympathetic nerves, green). b–f, The ear skin of vehicle treated controls (DMSO) or TRPV1+ nociceptor ablated (RTX) mice was treated with topical IMQ cream daily. (b) Ear thickness was measured relative to the contralateral ear at indicated time points (n=10–15 mice per time point; *, P < 0.02). (c) Representative histological sections of IMQ treated ears at day 6 stained by H&E. (d) Total inflammatory monocytes (n=10) and (e) total neutrophils in skin at day 3 (n=10; **, P < 0.005). (f) Total cell number in auricular lymph nodes at day 3 (n= 20; *, P = 0.01; ***, P < 0.001). g–j, IMQ was applied daily to (g,h) WT (n=10) and LTα −/− mice (n=6) or (i,j) vehicle treated (n=10) and FTY720 treated mice (n=10) and (g,i) ear swelling was measured at indicated time points. (h,j) The percentage of CD45+ leukocytes was determined in ear skin digests on day 6.

To dissect the roles of sympathetic fibers and nociceptors in the IMQ-model, mice were treated systemically with either 6-hydroxydopamine (6OHDA) or resiniferatoxin (RTX) to ablate TH+ sympathetic neurons or TRPV1+nociceptors, respectively (Extended Data Figs. 1&2)11,17. Subsequently, IMQ was applied topically to one ear and the ensuing inflammatory response was assessed based on the change in ear thickness, size of the myeloid infiltrate (Extended Data Fig. 3a) and tissue contents of inflammatory cytokines.

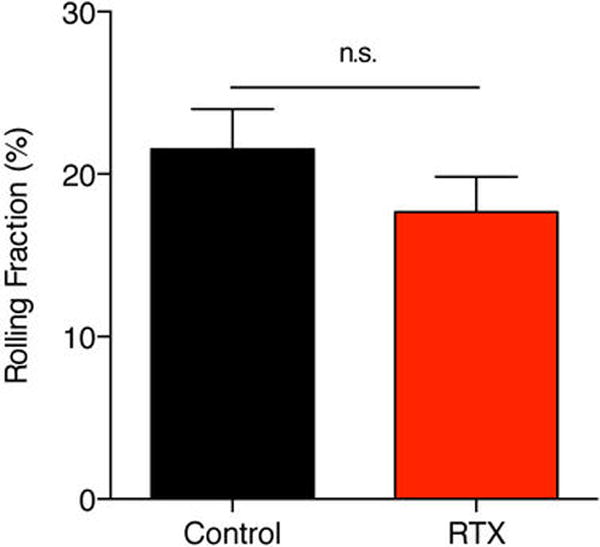

Following sympathetic denervation, IMQ-induced ear swelling was reduced compared to controls (Extended Data Fig. 1c); however, the inflammatory infiltrate was increased, while IL-17A, IL-17F, IL-22 and IL-23-p40 production remained unchanged (Extended Data Fig. 1d–i). Thus, sympathetic innervation exerts little or no direct local control over the inflammatory skin response. The observed changes were likely due to cardiovascular effects and/or global immune dysregulation following systemic sympathectomy (Supplementary Information)5. By contrast, in RTX-treated mice both ear swelling and inflammatory infiltrates in IMQ-exposed ears were profoundly reduced (Fig. 1b–e; Extended Data Fig. 4a–d). RTX treatment did not alter the systemic supply of inflammatory cells (Extended Data Fig. 4e–f)18. Moreover, intravital microcopy of ear skin revealed similar leukocyte rolling in RTX-treated and control mice (Extended Data Fig. 5), indicating that the absence of nociceptors did not affect the baseline adhesiveness of dermal microvessels19. More likely, ablation of TRPV1+ sensory nerves reduced IMQ-induced inflammation via local, extravascular mechanisms. However, the attenuated inflammatory response was not limited to the skin, as the IMQ-induced enhancement in cellularity of the draining auricular lymph node (LN) was also blunted by RTX (Fig. 1f).

LNs have a critical function in dermal antigen presentation to naive T-cells and generation of migratory effector cells. LNs also possess peripheral innervation20, which could have been altered by RTX; however, the role of skin-draining LNs during psoriatic inflammation is unclear. To address this issue, we tested the effect of IMQ in lymphotoxin-α-deficient (LTα−/−) mice, which are devoid of LNs. Compared to WT mice, there was no statistical difference in ear thickness, frequency, or composition of the inflammatory infiltrate in ears of LTα−/− mice (Fig. 1g&h). Additionally, we treated WT mice with FTY720, which blocks T cell egress from LNs preventing trafficking of effector cells to peripheral tissues21. Again, IMQ elicited full-fledged inflammation in exposed ears (Fig. 1i&j), indicating that T cell priming in skin draining LNs is dispensable for the acute induction of psoriasiform inflammation. Together, these findings imply that TRPV1+ nociceptors promote local immune responses directly in the skin.

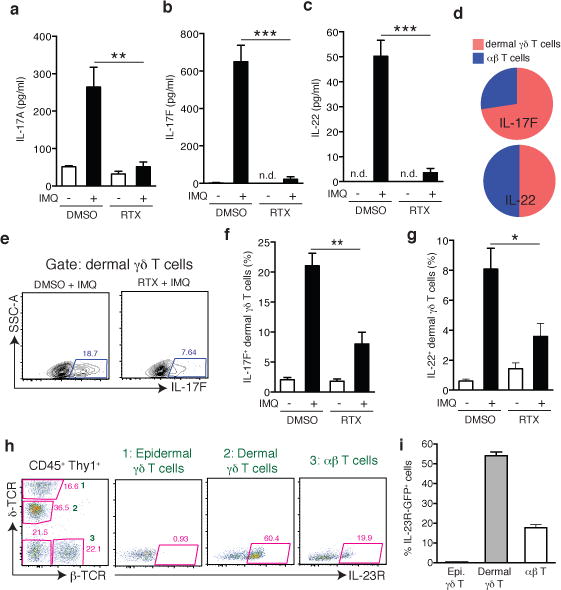

Neutrophil recruitment to the skin and keratinocyte hyperproliferation, hallmarks of IMQ-induced inflammation, are driven by IL-17 and IL-22, respectively2,7,12 so we asked whether nociceptors regulate the production of these cytokines. Indeed, after IMQ treatment, protein levels of IL-17A, IL-17F, and IL-22 had dramatically increased in ears of control mice, while in RTX-treated mice IL-17A was very low and IL-17F and IL-22 remained below the detection limit (Fig. 2a–c). Thus, TRPV1+ nociceptors control the generation of several key effector cytokines in psoriasiform dermatitis.

Figure 2. TRPV1+ nociceptors control IL-17F and IL-22 production by IL-23R+ dermal γδ T cells.

a–c, After 3 days of IMQ challenge, ears from vehicle- (DMSO; n=5) or RTX-treated mice (n=5) were harvested to perform ELISA for (a) IL-17A, (b) IL-17F, and (c) IL-22. (**, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001). d–g, Flow cytometry on digested ear skin was performed on day 6 of IMQ challenge. (d) Relative frequency of IL-17F+ or IL-22+ dermal γδ T cells and αβ T cells in IMQ treated control mice (n=15). (e) Representative FACS plots of IL-17F staining in dermal γδ T cells from vehicle (DMSO) and RTX treated mice. Quantification of frequency of (f) IL-17F+ and (g) IL-22+ amongst dermal γδ T cells in DMSO and RTX mice (n=5/group; *, P < 0.05; **, P = 0.01). h, Representative FACS plots of normal ear skin from an IL-23RGFP/+ mouse and i, quantification of frequency of IL-23R-GFP+ cells among skin resident Thy1+ T cell subsets (n=8).

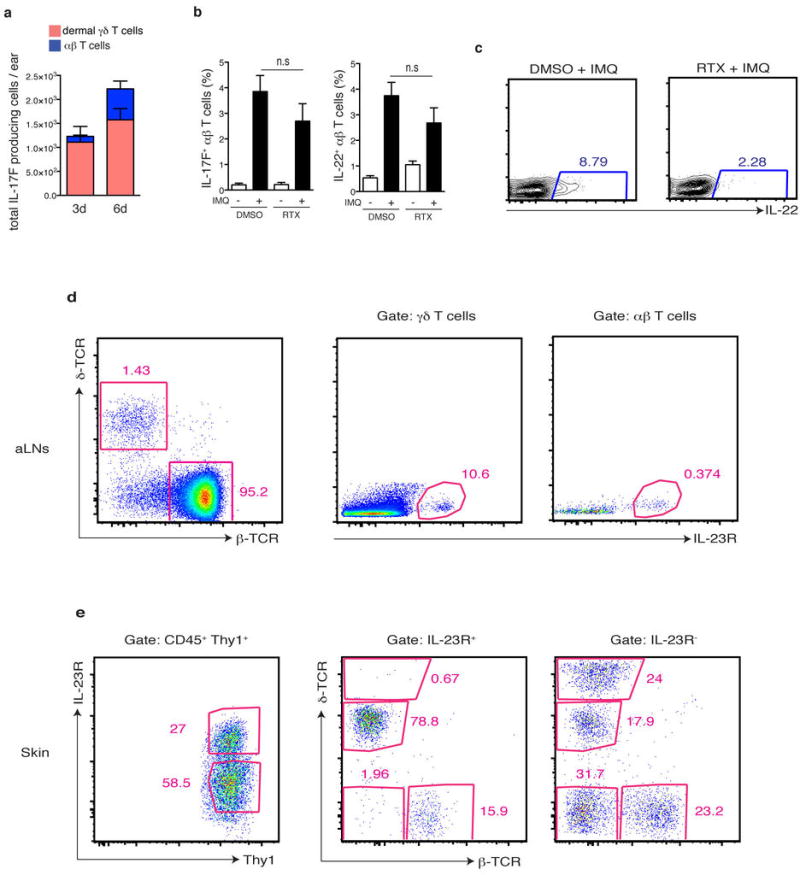

Since our findings in FTY720-treated mice suggested that recruitment of LN derived effector T-cells is not needed for IMQ-induced skin inflammation, we asked whether nociceptors regulate cytokine production by skin-resident lymphocytes, particularly γδT17 cells, which produce IL-17F and IL-22 (ref. 3,22,23). In ears of IMQ-treated control mice, most IL17F+ lymphocytes were dermal γδ T cells, while few conventional αβ T cells expressed IL-17F (Fig. 2d; Extended Data Figs. 3b & 6a). In RTX-treated mice, both IL-17F+ and IL-22+dermal γδ T cells were significantly reduced, indicating that TRPV1+ neurons drive the local production of IL-17F and IL-22 primarily by γδT17 cells (Fig. 2e–g; Extended Data Fig. 6b,c). These T-cells seed the skin in early life and are poised for rapid IL-17 production upon stimulation by IL-23 (ref. 24). Indeed, in ears of IL-23RGFP/+ mice25, ~60% of dermal γδT17 and ~20% of αβ T-cells expressed IL-23R (Fig. 2h&i), whereas T-cells in auricular LNs and epidermal γδ cells expressed little or no IL-23R (Extended Data Fig. 6d&e).

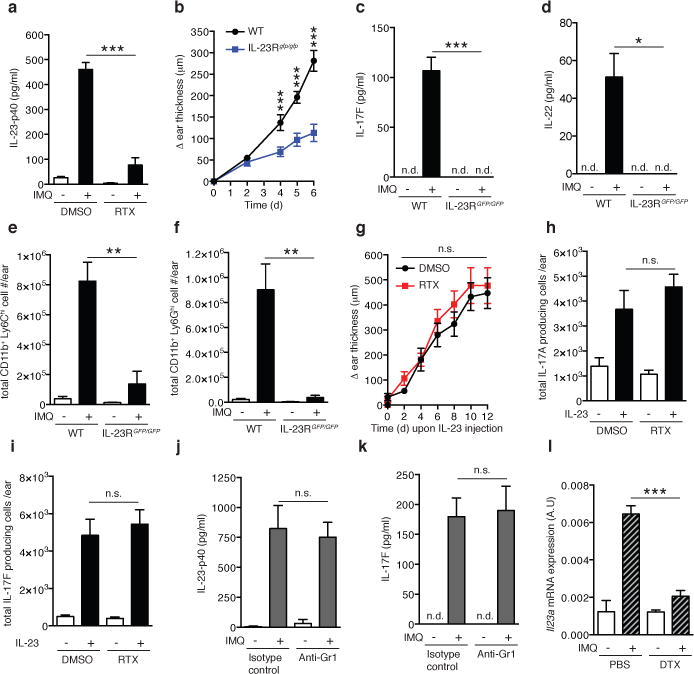

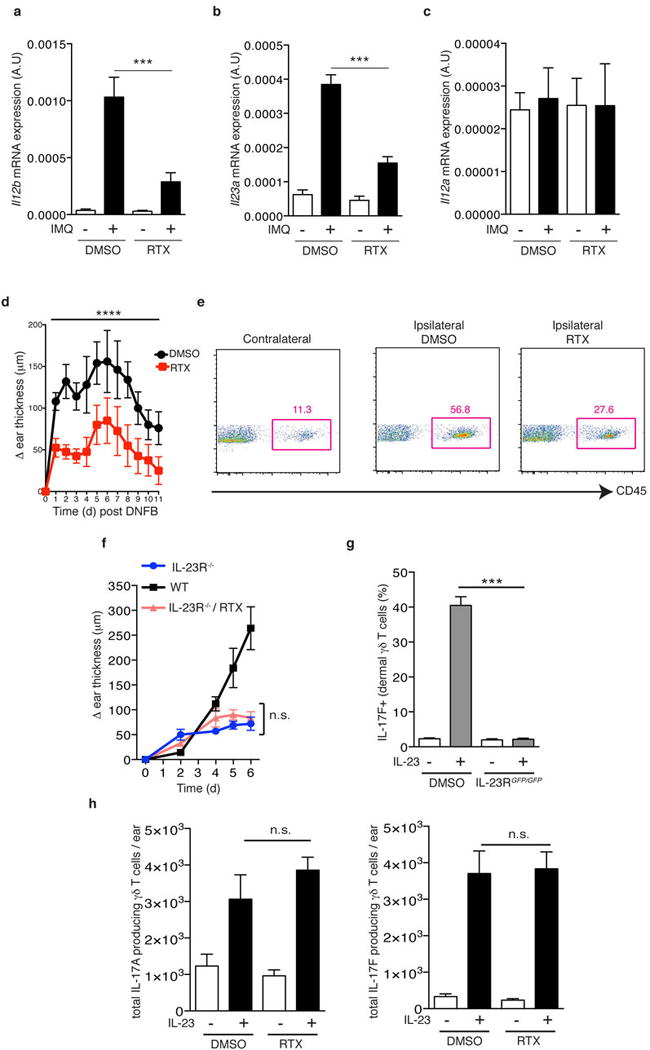

In light of the preferential expression of IL-23R on dermal γδT17 cells, the known role of IL-23 as a driver of IL-17 and IL-22 generation in psoriasiform inflammation13 and our finding that RTX pretreatment profoundly diminished IMQ-induced cytokine production by γδT17 cells, we hypothesized that TRPV1+ nociceptors might control dermal IL-23 production. Topical IMQ treatment of control mice dramatically increased p40 protein levels, as well as mRNA levels of il12b (IL-12/23p40) and il23a (IL-23p19), but not il12a (IL-12p35). These effects were nearly abolished after RTX treatment (Fig. 3a; Extended Data Fig. 7a–c), suggesting that TRPV1+ nociceptors are essential for cutaneous IL-23 production. It seems unlikely that IL-12 had a major impact in the IMQ model, because IMQ-induced inflammatory parameters were markedly reduced in IL-23RGFP/GFP mice, which respond to IL-12 but not IL-23, (Fig. 3b–f). However, IL-12-dependent skin inflammation induced using a chemical irritant, DNFB26, was profoundly reduced in RTX-treated mice, suggesting that RTX-sensitive fibers also play a role in IL-12-driven dermatitis (Extended Data Fig. 7d&e).

Figure 3. Dermal DC-derived IL-23 is critical to drive psoriasiform skin inflammation and acts downstream of RTX sensitive nociceptors.

a, After 3 days of IMQ challenge of vehicle (DMSO) or RTX treated mice, ears were harvested and total protein was prepared to quantify IL-23p40 by ELISA (n=5/experiment;***, P < 0.001). b, Ears of WT or IL-23RGFP/GFP mice (n=5/group) were treated daily with IMQ and ear thickness was measured relative to the contralateral ear at indicated time points (***, P < 0.001). c–f After 3 days of IMQ challenge in WT (n=5) or IL-23RGFP/GFP mice (n=4) total protein was prepared from ear skin and (c) IL-17F and (d) IL-22 were quantified by ELISA (*, P < 0.05; ***, P < 0.001). Cell suspensions from exposed ears stained for (e) inflammatory monocytes and (f) neutrophils to assess total numbers (n=5/experiment; *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01). g–i, IL-23 was injected intradermally every other day into ears of DMSO or RTX treated mice (n=8/group). (g) Ear thickness was measured as indicated. After 3 days, (h) IL-17A and (i) IL-17F producing Thy1+ cells per ear were quantified by FACS (n=5). j,k, Mice were treated with anti-Gr1 to deplete neutrophils and inflammatory monocytes or isotype-matched control mAb and challenged with IMQ for 3 days. Ear skin protein lysates were analyzed for (j) IL-23p40 and (k) IL-17F by ELISA (n=5). l, CD11c-DTR mice were treated with diphtheria toxin (DTX) or PBS 12 h prior to IMQ challenge. After 6h, ears were harvested and processed for total RNA isolation and il23a mRNA levels analyzed by qPCR (n=4; ***, P = 0.001).

Of note, while IL-17F and IL-22 production as well as myeloid infiltrates were virtually abolished in IL-23RGFP/GFP mice, ear swelling was only partially reduced (Fig. 3b–f), suggesting that topical IMQ promotes modest tissue edema through an IL-23 independent pathway. This activity was independent of nociceptors since RTX treatment of IL-23RGFP/GFP mice had no effect on the IMQ-induced swelling (Extended Data Fig. 7f).

While the above findings clearly demonstrate that nociceptors are indispensable for IMQ-induced dermal IL-23 production, it remained possible that nociceptive fibers exert additional proinflammatory functions, e.g. by directly regulating γδT17 cells. To address this, we performed intradermal IL-23 injections, which trigger psoriasiform skin inflammation in murine skin12. Regardless of whether nociceptors were ablated or left intact, IL-23 administration resulted in profound ear swelling and fully rescued IL-17 and IL-22 production by Thy1+ cells (Fig. 3h–i) and γδT17 cells (Extended Data Fig. 7g&h). Together, these results suggest that the proinflammatory function of TRPV1+neurons is rooted exclusively in the promotion of IL-23 production, at least in this experimental setting.

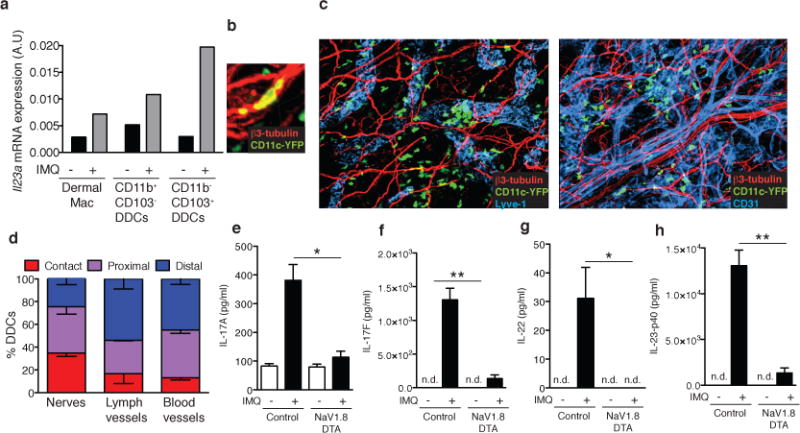

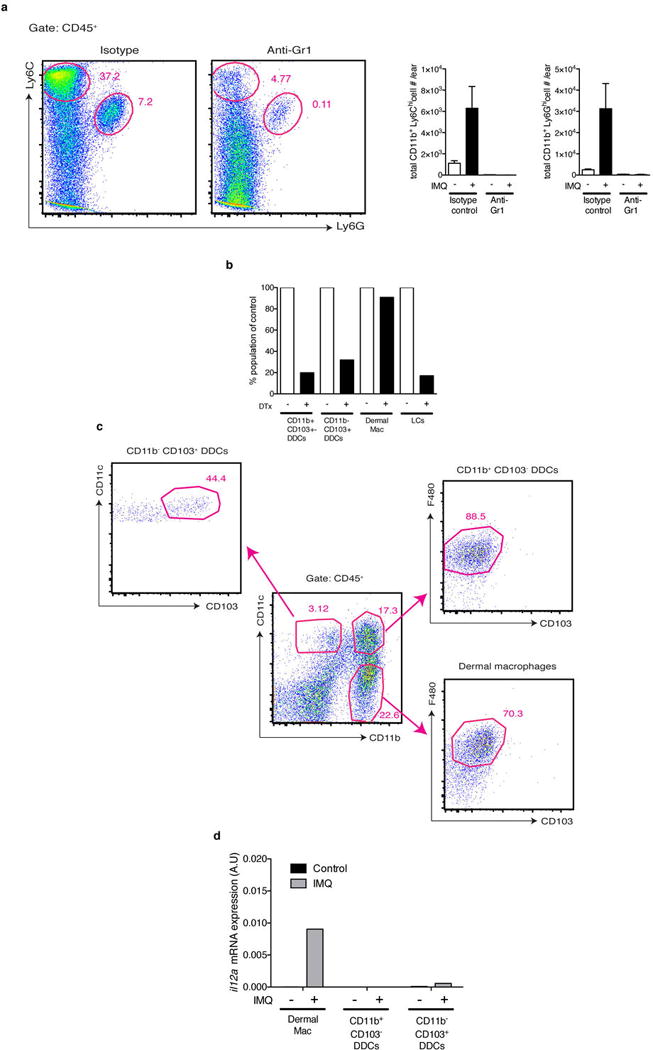

Next, we sought to identify the IL-23 producing cell type(s) regulated by TRPV1+ nociceptors. In intestinal barrier tissues, Ly-6Chigh inflammatory monocytes were identified as a major source of IL-23 in a colitis model27. However, depletion of neutrophils and inflammatory monocytes with anti-Gr-1 did not affect IMQ-induced dermal IL-23-p40 or IL-17F levels (Fig. 3j&k, Extended Data Fig. 8a), suggesting that skin-resident DCs and/or macrophages rather than migratory myeloid cells were the critical source of IL-23. Thus, we injected CD11c-diptheria toxin receptor (DTR) mice with diphtheria toxin (DTX), which depleted dermal DCs (DDCs) and Langerhans cells (LCs), but not macrophages (Extended Data Fig. 8b&c). Following DTX treatment, IMQ-induced expression of il23a mRNA was dramatically reduced in treated ears (Fig. 3l). Although these results do not discriminate between the relative contributions of LCs and dDCs to IL-23 production, IL-34 deficient mice, which selectively lack LCs are not impaired in IMQ-induced skin inflammation8. We focused our analysis on DDCs which can be further subdivided into CD103+ and CD11b+ subsets28. Both DC subsets, as well as macrophages, were FACS sorted from IMQ-treated and control ears to measure mRNA for il23a and il12a. Although CD103+ DDCs showed the most dramatic upregulation of il23a mRNA, taking into consideration that CD11b+ DDCs are more abundant, we estimate that the latter subset produced ~75% of the il23a mRNA, consistent with a recent report (Fig. 4a; Extended Data Fig. 8c&d)29.

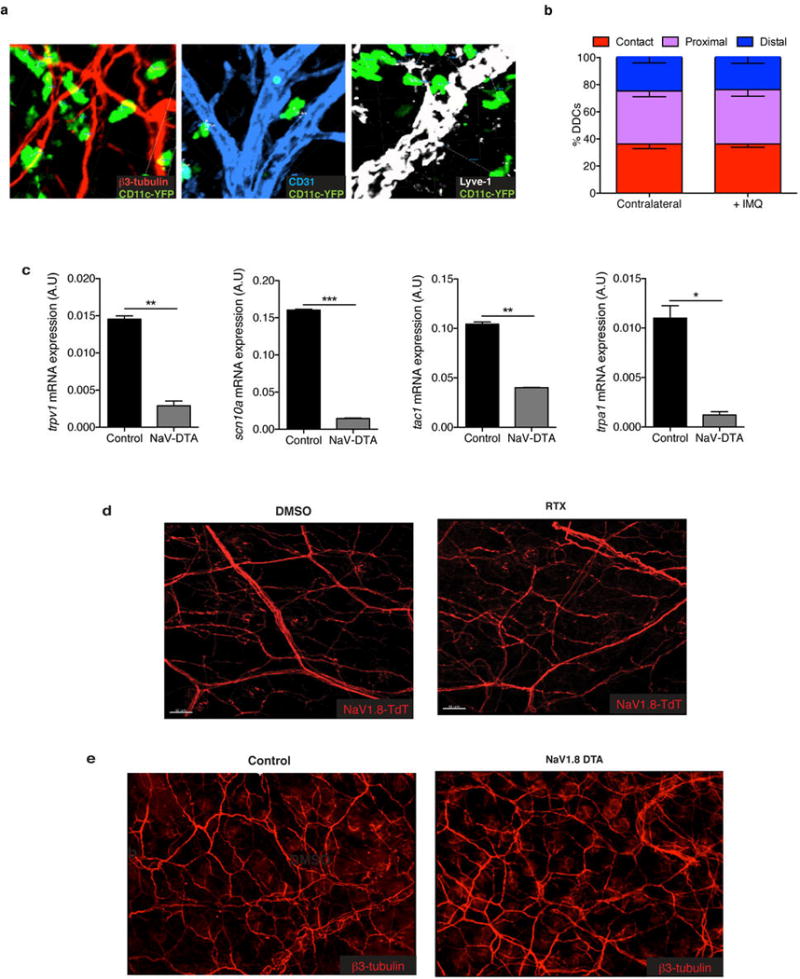

Figure 4. Dermal DCs (DDCs) are closely associated with cutaneous nerves and depend on NaV1.8+ nociceptors for IMQ induced IL-23 production.

a, Mice were challenged with IMQ (n=20 pooled mice/condition) and after 6h, myeloid cell populations comprising dermal macrophages and two subsets of DDCs were FACS sorted (Extended Data Fig. 8c) from cell suspensions to measure il23a mRNA by qPCR. b, Representative confocal micrographs of ear skin whole mounts from CD11c-YFP mice stained for β3-tubulin (peripheral nerves, red) and Lyve-1 (collecting lymphatics, blue) or CD31 (blood and lymphatic endothelial cells, blue). Original magnification was 200X. c, Close-up confocal micrograph of a CD11c-YFP cell in contact with a nerve (see also Suppl. Videos 1&2). d, Quantification of 3D DDC proximity to peripheral nerves, lymphatics, and blood vessels in normal ear skin. The frequency of DDCs (n=330) in contact, proximal (0–7μm) and distal (>7μm) to nerve fibers was determined as described in Methods and a Chi-square test showed bias of DDC to nerves relative to lymphatics and blood vessels (***P< 0.0001).e–h, Ears of NaV1.8-DTA or control littermates were treated daily with IMQ. Total protein was prepared from ear skin after 3 days and (e) IL-17A, (f) IL-17F, (g) IL-22 and (h) IL-23p40 were quantified by ELISA (n=4 ears/condition; *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01).

Having identified DDCs as the principal source of IMQ-induced IL-23, we sought to characterize the spatial relationship between DDCs and cutaneous nerves. Remarkably, confocal microscopy of skin whole mounts revealed that at steady state ~75% of DDCs were either in direct contact or in close proximity to sensory nerves (Fig. 4b–d; Extended Data Fig. 9a). Interactions were apparent along the entire length of nerves suggesting that DDCs may receive signals from unmyelinated nociceptor axons and not just from nerve terminals. However, given the high density of peripheral nerves in the skin, it was difficult to judge whether the association with DDCs occurred merely by chance or reflected a biased distribution. To address this possibility, we compared DDC localization relative to two other dense anatomical structures: blood and lymph vessels. In resting tissues contacts of DDCs with these microvascular networks were only about half as frequent as with peripheral nerves (Fig. 4d).

Of note, even though inflammation enhances DC motility and egress into draining lymphatics, IMQ-challenge did not alter the frequency of DDCs contacting nerves (Extended Data Fig. 9b), suggesting that dDCs engaged in dynamic interactions with nociceptors. We reconstituted NaV1.8-TdT mice with CD11c-YFP bone marrow and performed time-lapse multiphoton–intravital microscopy (MP-IVM) in ear skin to generate three-dimensional time-lapse videos of interactions between YFP+DDCs and TdT+ nociceptors. These interactions were highly diverse (Suppl. Video 1); some DDCs seemed to be anchored on nerves and sometimes extended protrusions to probe the surrounding tissue, while others appeared to use nerve fibers as a scaffold for directional migration (Suppl. Video 2).

Together, our results support the idea that DDCs can physically interact with a subset of nociceptors that regulate the production of IL-23. However, it should be cautioned that the pharmacological target of RTX, TRPV1, is also expressed on some non-neuronal cells10 so we sought an alternative to confirm the role of nociceptors in an experimental system that does not rely on pharmacologically targeting TRPV1. To this end, we employed NaV1.8-diptheria toxin (DTA) mice in which NaV1.8+ fibers, which respond to mechanical pressure, inflammatory pain and noxious cold, are selectively deleted9. Although nociceptor-associated transcripts in dorsal root ganglia were more profoundly reduced in this genetic model than after RTX treatment, trpv1 mRNA levels were only reduced by ~80%, consistent with the fact that noxious heat sensing fibers express TRPV1, but not NaV1.8 (Extended Data Fig. 2c & 9c)9. Following IMQ challenge, ears of NaV1.8-DTA mice contained very low protein levels of IL-17A, IL-17F, IL-22 and IL-23-p40 as compared to littermate controls (Fig. 4e–h). We conclude that NaV1.8−TRPV1+ neurons are insufficient to induce IL-23 production; rather, NaV1.8+TRPV1+ nociceptors are driving the response.

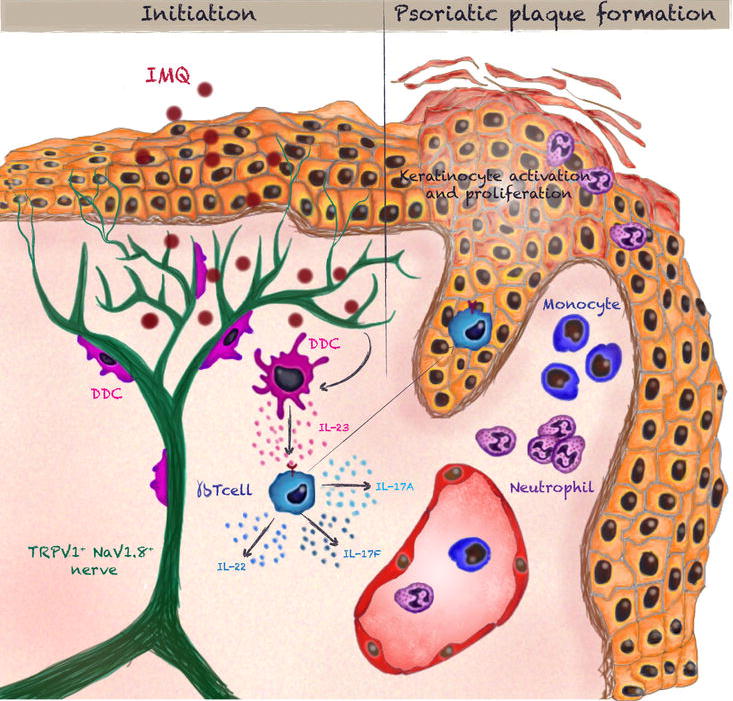

In light of these results, we propose a model of cutaneous neuroimmune interactions (Extended Data Fig. 10) whereby dermal NaV1.8+TRPV1+ nociceptors are essential to induce IL-23 production by nearby DDCs. IL-23 then acts on IL-23R+ γδT17 cells to induce IL-17F and IL-22 secretion, which precipitates the recruitment of circulating neutrophils and monocytes driving psoriasiform skin inflammation. The fact that both RTX and NaV1.8-DTA mice largely preserve a dense meshwork of dermal nerves (Extended Data Fig. 9d&e) implies that DDCs do not simply rely on nerves as a scaffold from which to produce IL-23. More likely, NaV1.8+TRPV1+ nociceptors actively induce and control IL-23 production.

While further studies will be needed to dissect the precise molecular underpinnings of neuroimmune communication in the skin (Supplementary Information), the present findings indicating nociceptor mediated control of DDCs and the IL-23/IL-17 axis open new avenues for the treatment of inflammatory diseases in the skin and perhaps elsewhere. Intriguingly, recent work has shown that NaV1.8+ nerve fibers exert immunosuppressive activity during S. aureus infection30, raising the possibility that some pathogens have evolved mechanisms to subvert the proinflammatory function of nociceptors. Together, this recent work and the present study suggest an emerging new paradigm whereby TRPV1+NaV1.8+ nociceptive fibers integrate environmental signals to modulate local immune responses to a variety of infectious and inflammatory stimuli.

Methods Summary

Published mouse strains used in this study are referenced in the online Methods. NaV1.8-Cre mice were bred with Rosa26-DTA and Rosa26-TdT mice in order to generate NaV1.8-DTA mice for functional studies and NaV.1.8-TdT mice for imaging, respectively. TRPV1+ nociceptors were deleted using three escalating doses (30 μg/kg, 70 μg/kg, and 100 μg/kg) of resiniferatoxin (RTX) as described11. To induce psoriasiform ear inflammation, 8–12 week old mice were treated topically with 5% IMQ cream or injected with 500 ng/ear rIL-23. Ear thickness was measured using an engineer’s micrometer (Mitutoyo). Cytokines were quantified from skin protein extracts by ELISA (Biolegend, R&D). For flow cytometric analysis of tissue leukocyte markers and intracellular cytokines, single-cell suspensions from ear skin were prepared by enzymatic digestion4. Imaging of fixed skin tissue was performed using an Olympus Fluoview BX50WI inverted microscope, while MP-IVM in live anesthetized mice was performed using an upright microscope (Prairie Technologies) with a MaiTai Ti:sapphire laser (Spectra-Physics). All animal studies were approved by the IACUC of Harvard Medical School and complied with NIH guidelines.

Methods

Mice

C57BL/6 mice, 4–8 weeks old, were purchased from Charles River or the Jackson Laboratory and female mice were used in experiments. IL-23RGFP/GFP mice25 in which GFP is knocked into the cytoplasmic tail of IL-23R and the homozygous GFP mouse acts as a functional receptor knockout were provided by M. Oukka and both male and female mice were used in experiments. CD11c-YFP mice31 were a gift from M. Nussenzweig and both male and female mice were used in experiments. LTα−/− mice32 were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory and male mice were used in experiments. CD11c-DTR33 mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratory and both male and female mice were used in experiments. NaV1.8-Cre mice were previously described9. Rosa26-DTA mice and Rosa26-TdTomato mice, which express a floxed-STOP cassette upstream of the ubiquitously expressed Rosa26-Diphtheria Toxin or Rosa26-TdTomato construct respectively, were purchased from Jackson Laboratory. NaV1.8-Cre male mice were bred with Rosa26-DTA and Rosa26-TdTomato female mice in order to generate NaV1.8-DTA for functional studies and NaV.1.8-TdT for imaging experiments respectively of which both matched male and female litters were used in experiments. Glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP)-Cre-TdTomato mice were generated by crossing heterozygous GFAP-Cre mice34 purchased from Jackson Laboratory with Rosa26-TdTomato mice. MHC-II-GFP mice35 were provided by M. Boes. Bone marrow chimeras were generated by irradiating NaV1.8-TdT mice or GFAP-Cre-TdT mice with two split doses totaling 1,300 rad and reconstituting with CD11c-YFP or MHC-II-GFP unfractionated bone marrow injected intravenously respectively. Bone marrow chimeras were allowed to rest for 12 weeks before use. Mice were all housed in specific pathogen-free conditions in accordance with the National Institutes of Health and all experimental animal protocols were approved by the IACUC at Harvard Medical School. For most animal experiments since the contralateral ear served as a control for the ear in which an inflammatory stimulus was applied, no randomization was used. Investigators were blinded for the initial ear-swelling experiments and subsequently no blinding was used.

Denervation

Resiniferatoxin (RTX), a capsaicin analogue, was injected subcutaneously into the flank of 4 week-old mice in three escalating (30 μg/kg, 70 μg/kg, and 100 μg/kg) doses on consecutive days11. Control mice were treated with vehicle solution (DMSO in PBS). Mice were allowed to rest for 4 weeks before denervation was confirmed by tail-flick assay. The tail-flick assay was conducted by holding mice vertically in a relaxed fashion allowing their tail to be immersed in a temperature-controlled water bath maintained at 52°C. Denervated mice exhibited a tail-flick latency of >10 seconds. Besides insensitivity to noxious heat stimuli, overall behavior qualitatively remained unaltered in RTX-treated mice. For chemical sympathectomy, Mice were intraperitoneally injected with 80 mg/kg 6-OHDA in 0.01% ascorbic acid in PBS at day −3. Control mice received injections of 0.01% ascorbic acid in PBS17.

Imiquimod Treatment, IL-23 injection, DNFB Treatment and Ear Measurement

Mice, 8–12 weeks old, of indicated genotypes or pharmacological treatments were treated with 5 mg of 5% imiquimod cream (IMQ) applied topically to dorsal and ventral aspects of ear skin totaling 125 μg of IMQ/day. Mice were treated starting on day 0 three times and sacrificed for analyses on day 3 or were treated six times and sacrificed for analyses on day 6. Interleukin-23 (IL-23) was injected intradermally into the dorsal aspect of the ear skin as a 50 μg/mg solution in 10 μL PBS (500 ng/ear). Contralateral ears were injected with PBS alone. A 0.5% solution of DNFB in Acetone was applied to the dorsal and ventral aspects of ear skin without prior sensitization. Ear thickness was measured using an engineer’s micrometer (Mitutoyo) at indicated timepoints and the Δ ear thickness is calculated as the change in ear thickness from the treated ear relative to the contralateral naïve or vehicle treated ear.

FTY720 Treatment and In Vivo Depletion of Dendritic Cells or Inflammatory Monocytes/Neutrophils

FTY720 (1 mg/kg) or PBS was injected daily intraperitoneally commencing at Day 0 of IMQ challenge. Efficacy of treatment was confirmed by a dramatic reduction in circulating lymphocytes from peripheral blood (data not shown). In order to deplete dendritic cells from skin, CD11c-DTR mice33 were injected at Day (−1) with 4ng of diphtheria toxin / g mouse, a dose which is nontoxic to murine cells not expressing the diphtheria toxin receptor36. Depletion of dermal DCs and Langerhans cells, but not macrophages, was confirmed by flow cytometry (Suppl. Fig. 8). In order to deplete neutrophils and inflammatory monocytes, 500 μg of anti-Gr1/mouse (clone: RB6-8C5; BioXCell), was injected intraperitoneally at Days −1, 0, 1 and 2. Depletion was confirmed by flow cytometry of peripheral blood as well as challenged ear skin showing a paucity of neutrophils and inflammatory monocytes (Suppl. Fig. 8).

Histology

Ears were embedded in paraffin and submitted for histological analysis by haematoxylin and eosin staining to the Harvard Rodent Histopathology Core.

Whole-mount immunofluorescence of ear skin

Ears were harvested and split into dorsal and ventral halves. After fixation in 4% paraformaldehyde, any adherent cartilage was removed under a dissecting microscope in order to expose the dermis evenly for imaging. Tissue was blocked in blocking buffer containing PBS with 0.5% BSA, 0.3% Triton X-100, 10% goat serum and Fc Block and also stained with the following antibodies in the same buffer. Unconjugated antibodies used include: anti-neuronal class III β-tubulin (clone TUJ1; Covance), anti-tyrosine hydroxylase (clone A2B5-105; Millipore), anti-Lyve1 (clone ALY7; eBiosciences), anti-peripherin (Polyclonal; Abcam), and anti-NeuN (A60; Millipore). Alexa488 conjugated antibodies include: anti-neuronal class III β-tubulin (clone TUJ1; Covance), goat anti-mouse IgG (Invitrogen) and goat anti Rabbit IgG. Alexa 647 conjugated antibodies include: goat anti-rat IgG and goat anti-rabbit IgG. Washing steps were performed in PBS with 0.2% BSA, and 0.1% Triton X-100. Ears were mounted with the dermis facing the imaging plane in FluorSave reagent (Calbiochem).

Confocal Microscopy

Confocal images were acquired on an Olympus Fluoview BX50WI inverted microscope with 10X/0.4, 20X/0.5, and 40X/1.3 magnification/numerical aperture objectives. For images used in three-dimensional analysis, image planes were acquired at 0.5 μM intervals through the imaging volume.

Intra-vital Two-Photon Microscopy

Anesthetized mice were placed on a custom-built stage and the ear fixed to a temperature-controlled metallic support to facilitate exposure of the dorsal aspect to a water-immersion 20X objective (0.95 numerical aperture) of an upright microscope (Prairie Technologies). A MaiTai Ti:sapphire laser (Spectra-Physics) was tuned between 870nm and 900nm for multiphoton excitation and second-harmonic generation. For dynamic analysis of cell interaction in four dimensions, several xy section (512×512) with z spacing ranging from 2μm to 4μm were acquired every 15–20 seconds with an electronic zoom varying from 1X to 3X. Emitted light and second-harmonic signals were directed through 450/80-nm, 525/50-nm and 630/120-nm bandpass filters and detected with non-descanned detectors. Post-acquisition image analysis, volume-rendering and four-dimensional time-lapse videos were performed using Imaris software (Bitplane scientific software).

Intravital Microscopy and Image Analysis

Intravital microscopy of skin was performed as previously described19. In brief, control or RTX treated mice were anesthetized and the left ear was exposed and positioned for epifluorescence intravital microscopy. Preparations were transferred to an intravital microscope (IV-500; Mikron Instruments, San Diego, CA), equipped with a Rapp OptoElectronic SP-20 xenon flash lamp system (Hamburg, Germany) and QImaging Rolera-MGi EMCCD camera (Surrey, BC). The fluorescent dye rhodamine-6G (20 mg/kg in PBS) was administrated through the catheterized right carotid artery to visualize circulating leukocytes. Cell behavior in skin venules was recorded in 10 min recordings through 10× or 20× water immersion objectives (Achroplan; Carl Zeiss). Rolling fractions in individual vessel segments were determined offline by playback of digital video files. Rolling fraction was determined as the percentage of cells interacting with skin venules in the total number of cells passing through a vessel during the observation period.

Cytokine Quantification by ELISA

Skin biopsies from ears were obtained using 10mm diameter skin biopsy punches (Acuderm, Inc). Samples were homogenized in Tissue Extraction Reagent I (Invitrogen) in the presence of protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche) using a gentleMACS dissociator (Miltenyi Biotec). Skin protein extracts were assayed for IL-17A, IL-22, IL-23p40, (Biolegend) and IL-17F (R&D Systems) in accordance with manufacturer’s instructions.

RNA Isolation and qPCR

RNA from sorted and pelleted cells was isolated using RNEasy Plus Mini Kit (Qiagen) including a gDNA elimination step. Ear skin and dorsal root ganglia (DRGs) were harvested and placed immediately in RNALater (Ambion) before homogenization and RNA isolation using Qiagen RNEasy Plus Mini Kit (Qiagen)9. DRGs for comparison of the efficacy of denervation were harvested from equivalent anatomical locations, typically consisting of the cervical and thoracic ganglia from C1-T2. cDNA synthesis was done using Superscript Vilo cDNA synthesis kit (Invitrogen) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Relative quantification of transcripts was done using validated Quantitect Primer Assays (Qiagen) combined with the QuantiTect SYBR Green Detection Kit (Qiagen) on a LightCycler 480 (Roche). Relative expression of genes was calculated to gapdh using the ΔCT method.

Tissue Digestion

Single-cell suspensions of lymph nodes, spleen, and bone marrow were generated as described previously20. For ear-skin digestion, the dorsal and ventral aspects of the ear were mechanically separated before mincing and placing into a digestion mix modified from E. Gray and J. Cyster4. Ears were digested for 80 minutes at 37°C in gentleMACS tubes (Miltenyi) with gentle agitation in freshly prepared digestion mix consisting of DMEM (Gibco) supplemented with HEPES (Invitrogen), 2% FCS, 100 μg/mL Liberase TM (Roche), 100 μg/mL DNase I (Roche) and 0.5 mg/mL Hyaluronidase (Sigma). After enzymatic digestion, the mixture was processed using a gentleMACS homogenizer (Miltenyi) in order to obtain a cell suspension, which was then filtered through a 70 μM cell strainer (BD). Cells were then resuspended in FACS buffer for analysis. If cell suspensions were to be analyzed for cytokine producing cells, ears were harvested and digested in the presence of Brefeldin A (Biolegend).

Flow Cytometry, Cell Sorting, and Cell Counts

Single-cell suspensions in FACS Buffer (PBS with 2 mM EDTA and 2% FCS (Invitrogen-GIBCO)) were pre-incubated with Fc-Block (clone 2.4G2) before staining for surface antigens. FITC-conjugated antibodies used include: anti-Ly-6G (Clone 1A8; BD Pharmingen), Alexa488-conjugated antibodies used include: anti-CD103 (Clone 2E7; Biolegend), PE-conjugated antibodies used include: anti-δ-TCR (Clone GL3; Biolegend), anti-Ly-6C (Clone HK1.4; Biolegend), PerCP/Cy5.5-conjugated antibodies used include: anti-CD45.2 (Clone 104; Biolegend), PE-Cy7-conjugated antibodies include: anti-TCR-B (Clone H57-597; Biolegend), anti-CD11c (Clone HL3; BD Pharmingen), Alexa647-conjugated antibodies used include: anti-CCR6 (Clone 140706; BD Pharmingen), anti-CD11b (Clone M1/70; Biolegend), APC-Cy7-conjugated antibodies used include: anti-Thy1.2/CD90.2 (Clone 30-H12; Biolegend), anti-I-A/I-E “Class-II” (Clone M5/114.15.2; Biolegend). Cells were then washed with PBS and resuspended in MACS buffer for immediate acquisition or fixed in Cytofix (BD Pharmingen) per manufacturer’s instructions for later acquisition. For analysis, cells were acquired on a BD FACS CANTO (BD Pharmingen) and analyzed using FlowJo software (Treestar Inc.). For intracellular cytokine staining, cells were not restimulated and rather harvested and digested in the presence of Brefeldin A (Biolegend). After staining for surface antigens, cells were then fixed and permeabilized using BD Cytofix/Cytoperm kit (BD Pharmingen) as per manufacturer’s instructions. Cells were stained in Perm/Wash buffer. Alexa488-conjugated antibodies used include: anti-IL-17A (Clone TC11-18H10.1; Biolegend), anti-IL-17F (Clone 9D3.1C8; Biolegend), Alexa647-conjugated antibodies used include: anti-IL-17A (Clone TC11-18H10.1; Biolegend), anti-IL-17F (Clone 9D3.1C8; Biolegend), and anti-IL-22 (Clone Poly5164; Biolegend). For determining total counts of cell subsets, an aliquot of the same cell suspension used for flow cytometry was stained for CD45.2 and acquired on an Accuri Cytometer (BD Biosciences) with a known amount of CountBright counting beads (Invitrogen). The total CD45+ cell number was then determined in the original cell suspension and used for total quantification of the cell number of each subset of interest defined by multi-parameter flow cytometry based on that subset’s frequency relative to the CD45+ population. For cell sorting, cells were stained for indicated surface markers and sorted using a BD FACSAria (BD Biosciences) into complete DMEM media prior to RNA extraction.

Image Analysis

Images from confocal microscopy and from two-photon microscopy were analyzed on either Volocity software (Improvision) or Imaris (Bitplane). For determining the distance of CD11c-YFP cells from nerves, lymphatics, or blood vessels, the centroid of DCs was calculated by an unbiased approach, and the distance between a given DC centroid and the closest nerve, blood vessel or lymphatic vessel was calculated using Imaris software. In order to bin cells into contact (<0 μm), proximal (0–7 μm), and distal (>7 μm) fractions, the calculated average radius of a DC (7.04 μm) was subtracted from each measured distance.

Statistical Analyses

Precise experimental numbers of animals are reported in the figure legends. Experiments were repeated at least three times except in Figure 2e, Figure 3e, Figure 3f, and Figure 3g in which two replicates were done assessing ten mice total in each experimental group overall. Some data, such as ear-swelling curves, represent pooled averages of the sum total of animals used in experiments whereas other data consists of a representative experiment of the independent experiments. All statistical analyses were performed using Prism (GraphPad Software) and results are calculated as means with error bars representing the s.e.m. Means between two groups were compared by using a two-tailed t-test. Means between three or more groups were compared by using a one- way or two-way ANOVA. A Chi-square statistical analysis was performed for Figure 4d comparing the total number of dendritic cells in contact, proximal and distal bins relative to nerves vs. lymphatic vessels or vs. blood vessels.

Extended Data

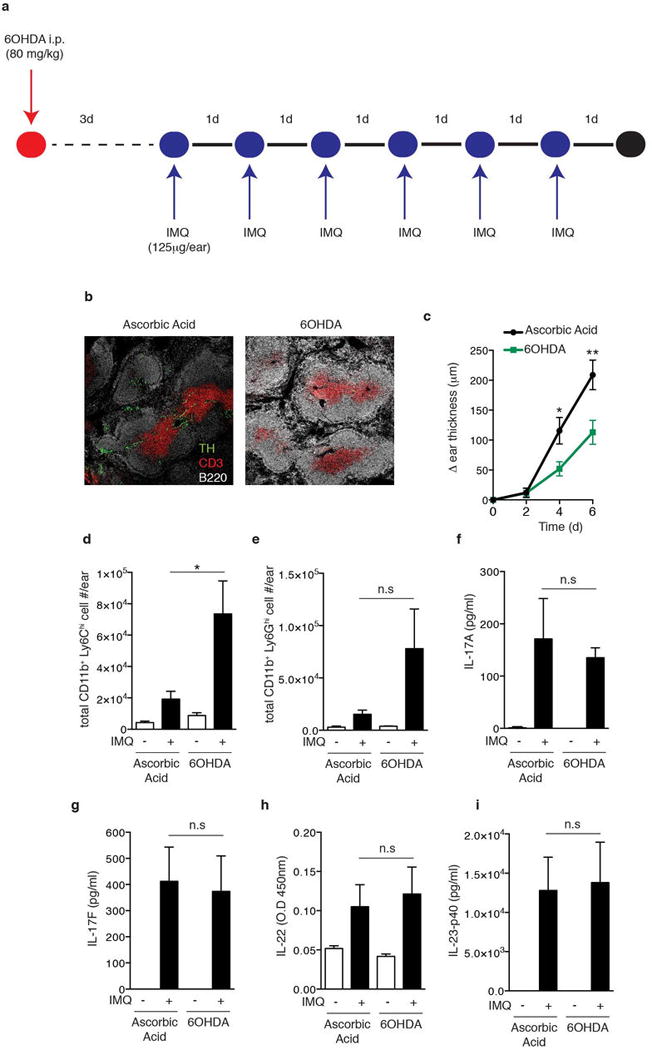

Extended Data Figure 1. 6-Hydroxydopamine (6OHDA) treatment ablates sympathetic nerve function and reduces ear swelling, but does not ameliorate the inflammatory response to IMQ treatment.

a, Experimental protocol: Mice were injected intraperitoneally with 6OHDA, resulting in a reversible chemical sympathectomy lasting ~two weeks. After a rest period of 3 days animals were challenged topically on the ear with IMQ. b, Representative section of splenic white pulp showing B cells (B220, white), T cells (CD3, red), and tyrosine hydroxylase+ (TH, green) nerve fibers in vehicle (ascorbic acid) treated and sympathectomized (6OHDA) mice. c–i. Analysis of the inflammatory response in ears of vehicle (ascorbic acid) treated and sympathectomized (6OHDA) mice after daily topical IMQ challenge: (c) timecourse of change in ear thickness of IMQ treated ear relative to the contralateral ear (n=10; *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01) and (d) total number of infiltrating monocytes and (e) neutrophils, and the amount of (f) IL-17A, (g) IL-17F, (h) IL-22 and (i) IL-23-p40 in protein extracts of IMQ exposed ears at day 3 (*, P < 0.05; n=5).

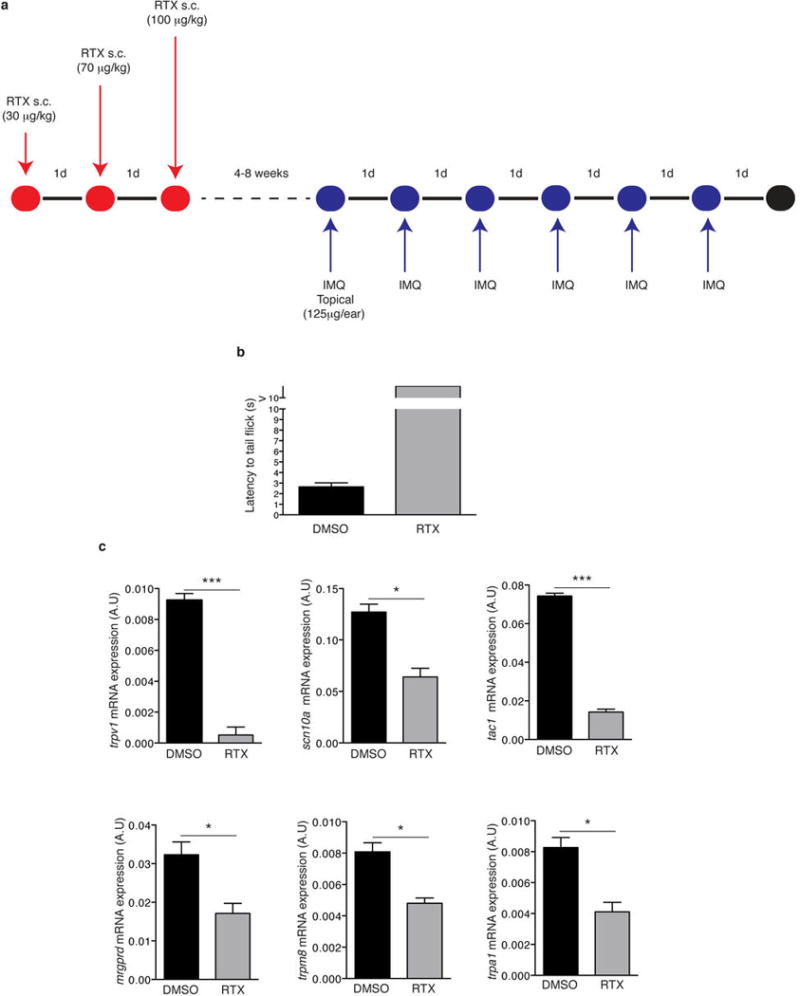

Extended Data Figure 2. Resiniferatoxin (RTX) treatment diminishes noxious heat sensation and decreases the expression of nociceptor markers on dorsal root ganglia (DRGs).

a, Schematic protocol of nociceptor ablation and induction of psoriasisform skin inflammation. RTX was injected subcutaneously into the back in three escalating doses (30 μg/kg, 70 μg/kg and 100 μg/kg) on consecutive days and mice were allowed to rest for at least 4 weeks before IMQ treatment. b, Denervation was confirmed by immersing the tail of mice into a temperature controlled water bath maintained at 52°C and the latency to the first tail movement to avoid water was measured (n=6). c, Total RNA was isolated from dorsal root ganglia (DRG; level C1-C7) of vehicle (DMSO) and RTX-treated mice and the levels of trvp1, scn10a (NaV1.8), tac1 (Substance P), trpm8 and trpa1 mRNA relative to gapdh were determined (n=3).

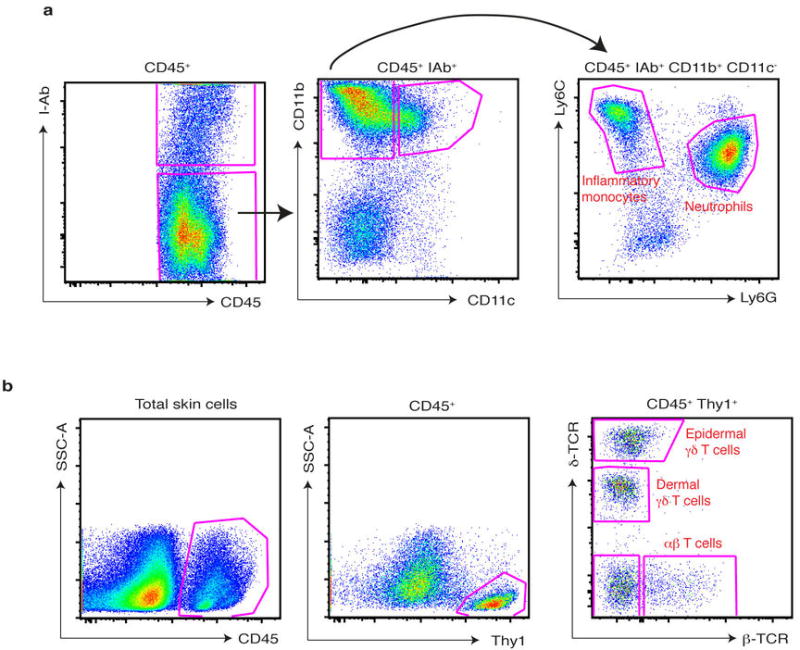

Extended Data Figure 3. Gating strategy for T cell subsets and myeloid cells from digested ear skin.

a, The ear skin of mice challenged for 3 days with IMQ was digested as described in methods and, after doublet exclusion and gating on defined FSC-A, SSC-A parameters, infiltrating myeloid cells were gated as CD45+ I-Ab (Class-II)−, CD11b+ CD11c−, and then subdivided into inflammatory monocytes and neutrophils based on Ly6C and Ly6G staining. b, The ear skin of naïve mice was digested as described in methods and, after doublet exclusion and gating on defined FSC-A, SSC-A parameters, cutaneous T cells were gated on CD45+, Thy1+, and then divided into subsets based on staining for δ-TCR and β-TCR.

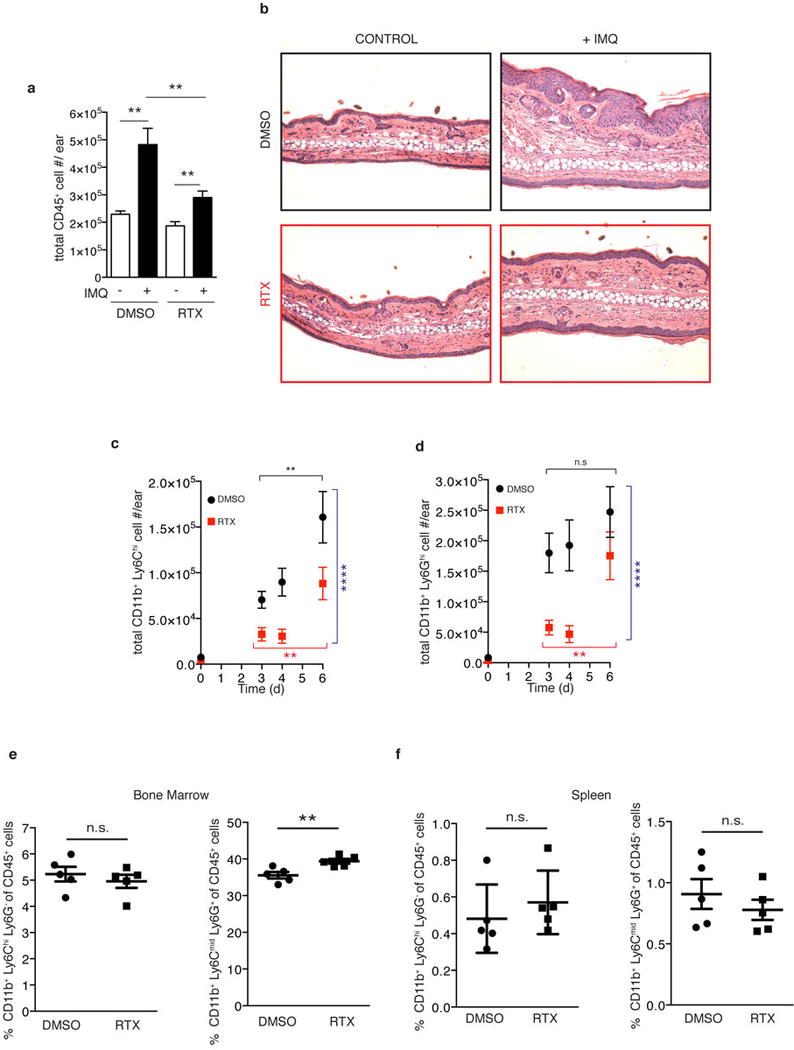

Extended Data Figure 4. RTX treatment reduces the immune cell infiltrate upon IMQ treatment in the skin but does not affect reservoirs of inflammatory monocytes and neutrophils at steady-state.

a, The ear skin of vehicle (DMSO) or sensory denervated (RTX) mice was treated with topical IMQ cream daily and the total numbers of CD45+ cells were determined on day 3 as explained in methods (n=10). b, Representative histological sections of untreated and IMQ treated ears at day 3 stained by H&E (20x) (n=5 per condition). c,d, Total inflammatory monocytes (CD45+, CD11b+, Ly6Chigh) and neutrophils (CD45+, CD11b+, Ly6Ghigh) were determined by flow cytometry (n=5–10 mice per time point). Two-way ANOVA was run to compare total numbers of inflammatory monocytes and neutrophils between DMSO and RTX conditions over days 3–6 (****, P< 0.0001). One-way ANOVA was run to compare total inflammatory monocytes and neutrophil numbers over days 3–6 within DMSO or RTX conditions (**, P< 0.003). e, Bone marrow was isolated from WT and RTX mice from one femur and the frequency of inflammatory monocytes (CD45+, CD11b+, Ly6Chigh, Ly6G−) and neutrophils (CD45+, CD11b+, Ly6Ghigh, Ly6Cmid) relative to CD45+ cells was determined by flow cytometry (n=5). f, Spleens from WT and RTX mice were processed for flow cytometry and the frequency of inflammatory monocytes (CD45+, CD11b+, Ly6Chigh, Ly6G−) and neutrophils (CD45+, CD11b+, Ly6Ghigh, Ly6Cmid) relative to CD45+ cells was determined (n=5).

Extended Data Figure 5. Leukocyte rolling fractions in skin venules of control and RTX-treated mice analyzed by intravital microscopy.

Combined results are shown for 26 venules from 5 control mice and for 20 venules from 4 RTX-treated mice. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM of four experiments.

Extended Data Figure 6. Dermal γδ T cells represent a major source of IL-17F and IL-22 in skin during IMQ challenge and already express IL-23R+ at steady state.

a, WT mice were challenged with IMQ and the total numbers of IL17F+ dermal γδ T cells and αβ T cells at 3 days (n=15) or 6 days (n=10) were quantified. b, Representative flow plots related to (Figure 2g) of gating for IL-22+ cells within dermal γδ T cells after 6 days of IMQ treatment. c, Ears of DMSO or RTX treated mice were exposed for 6 days to IMQ and the frequency of IL-17F+ and IL-22+ cells within αβ T cells was determined (n=5).d, Auricular lymph node (aLN) cells from IL-23RGFP/+ mice were analyzed by flow cytometry for expression of IL-23R-GFP+ cells within the γδ T cells and αβ T cell compartment at steady state (representative FACS plot from 8 mice analyzed). e, The ear skin from IL-23RGFP/+ mice was digested and analyzed by flow cytometry and the distribution of T cells subsets within IL-23R-GFP+ and IL-23R-GFP− fractions of Thy1+ cells determined (representative FACS plot from 8 mice analyzed).

Extended Data Figure 7. TRPV1+ nociceptors regulate the expression of il12b and il23a upon IMQ challenge, the inflammatory response to DNFB application, and IL-23 injection can bypass their contribution to activate γδ T cells.

a–c, After 3 days of IMQ challenge, ears were harvested and processed for total RNA isolation and (a) il12b (b) il23a and (c) il12a mRNA levels were analyzed by qPCR (n=5). d, DNFB (0.5% in acetone) was applied topically to DMSO and RTX mice. Time course of change in ear thickness of IMQ treated ear relative to the contralateral ear is represented (n=10). Two-way ANOVA was run to compare ear swelling under DMSO and RTX conditions over time (****, P < 0.0001). e, Representative FACS plots from ears harvested after 24h of DNFB application. f, IL-23R−/− mice were treated with RTX and then compared to WT and IL-23RGFP/GFP littermate controls during IMQ treatment. Ear thickness was calculated relative to the contralateral ear (n=5). g, After two IL-23 injections into the ear skin of WT and IL-23RGFP/GFP mice, the frequency of IL-17F+ cells within dermal γδ T cells was determined by flow cytometry (n=5). h, IL-23 was injected twice into the ear skin of Vehicle- and RTX-treated mice and the total numbers of IL17A+ or IL-17F+ dermal γδ T cells per ear were determined by flow cytometry (n=5).

Extended Data Figure 8. Selective depletion of migratory and skin resident myeloid cell subsets in ear skin and gating strategy used for sorting to isolate RNA from MHC-II+ cells in skin.

a, WT mice were treated with anti-Gr1 (clone RB6-8C5 to deplete neutrophils and inflammatory monocytes) or matched isotype control, challenged with IMQ for 3 days and skin was digested to quantify the total numbers of inflammatory monocytes and neutrophils per ear. Shown are representative plots pre-gated on CD45+ cells and quantification of cell numbers from n=3 mice. b, DTX treatment resulted in depletion of both subsets of dermal DCs (DDCs) as well as Langerhans cells (LCs) but not macrophages. Cells were gated as shown in (Extended Data Fig. 8c) and normalized to levels in WT mice based on the frequency within the CD45+ population from n=4 mice. c, Ear skin from naïve mice was digested and analyzed by flow cytometry for the indicated subsets. Shown is a representative plot pre-gated on CD45+ Class II+ cells from which further subsets were divided based on CD11b and CD11c expression and then F4/80 and CD103 as indicated. d, Total RNA from sorted cells was isolated and qPCR for il12a relative to gapdh was performed from naïve and IMQ treated ears after 6 hours from n=20 pooled mice.

Extended Data Figure 9. Dermal DCs (DDCs) are found in close apposition to NaV1.8+ nociceptors in skin, NaV-DTA mice express reduced levels of key nociceptor markers, yet nociceptor deletion does not grossly affect the peripheral neural network in skin.

a, Representative confocal micrographs of CD11c-YFP mice stained for β3-tubulin, Lyve-1 (collecting lymphatics), and CD31 (blood and lymphatic endothelial cells). b, 3D quantification of DDC proximity to peripheral nerves in naïve and 6 hours post-IMQ treatment binned into contact (<0 um), proximal (0–7 um) and distal (>7 um) fractions as explained in the methods (n of DCs = 200). c, Total RNA from dorsal root ganglia (DRGs) (C1–C4) of littermate control and NaV1.8-DTA mice was isolated and levels of mRNA for trpv1 (TRPV1), scn10a (NaV1.8), tac1 (Substance P) and trpa1 (TRPA1) were determined relative to gapdh. This demonstrates the efficacy of the NaV1.8-DTA system and combined with the original reference characterizing the pain phenotype of these mice illustrates that a subset of peptidergic TRPV1+ nerve fibers is spared. d, Representative confocal micrograph of whole mount ear skin of Vehicle- and RTX-treated mice showing preserved nerve scaffold and e, representative confocal micrographs of whole mount ear skin of Control and NaV1.8-DTA mice showing preserved nerve scaffold. While DRGs showed a loss of the hallmark ion channels of these nerve subsets (Extended Data Fig. 1c and Extended Data Fig. 9c), surprisingly we still observed that RTX mice and NaV1.8-DTA mice maintain a meshwork of nerves in the skin.

Extended Data Figure 10.

Summary Diagram.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank G. Cheng, M. Flynn and S. Omid for technical support; M. Perdue, L. Jones and E. Nigro for secretarial assistance; E. Gray for providing detailed protocols for flow cytometry of skin samples; J. Harris for discussion and providing detailed RNA isolation protocols of skin samples;R. T. Roderick for histopathology analysis; T. Liu and J. Ru-Rong for providing the RTX denervation protocol; M. Ghebremichael for statistical advice; F. Winau and J.L. Rodriguez-Fernandez for critical reading of the manuscript and members of the von Andrian lab for discussion and advice. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants AI069259, AI078897, AI095261, and AI111595 (to U.H.v.A.), NIH 5F31AR063546-02 (to J.O.M.) and Human Frontiers Science Program, Charles A. King Trust and National Psoriasis Foundation (to L.R.B).

Footnotes

Online Content

Extended Data Figures 1–10, 2 Videos, Full Methods, Supplementary Information and associated references are available with the online version.

Author Contributions

L.R.B., J.O.M., and U.H.v.A. designed the study. L.R.B., J.O.M., M.P., E.N., A.T., and D.A., performed and collected data from experiments and L.R.B., J.O.M., and E.N., analyzed data. J.N.W., provided reagents and gave conceptual advice. J.O.M., L.R.B., and U.H.v.A. wrote the manuscript. L.R.B., and J.O.M., contributed equally to this work.

No authors declare competing interests.

References

- 1.Nestle FO, Di Meglio P, Qin JZ, Nickoloff BJ. Skin immune sentinels in health and disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9:679–691. doi: 10.1038/nri2622. doi:10.1038/nri2622nri2622 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Perera GK, Di Meglio P, Nestle FO. Psoriasis. Annu Rev Pathol. 2012;7:385–422. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pathol-011811-132448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cai Y, et al. Pivotal role of dermal IL-17-producing gammadelta T cells in skin inflammation. Immunity. 2011;35:596–610. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.08.001. doi:10.1016/j.immuni.2011.08.001 S1074-7613(11)00306-2 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gray EE, Suzuki K, Cyster JG. Cutting edge: Identification of a motile IL-17-producing gammadelta T cell population in the dermis. J Immunol. 2011;186:6091–6095. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1100427. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.1100427 jimmunol.1100427 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rosas-Ballina M, et al. Acetylcholine-synthesizing T cells relay neural signals in a vagus nerve circuit. Science. 2011;334:98–101. doi: 10.1126/science.1209985. doi:10.1126/science.1209985 science.1209985 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chiu IM, von Hehn CA, Woolf CJ. Neurogenic inflammation and the peripheral nervous system in host defense and immunopathology. Nat Neurosci. 2012;15:1063–1067. doi: 10.1038/nn.3144. doi:10.1038/nn.3144 nn.3144 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van der Fits L, et al. Imiquimod-induced psoriasis-like skin inflammation in mice is mediated via the IL-23/IL-17 axis. J Immunol. 2009;182:5836–5845. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0802999. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.0802999 182/9/5836 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Flutter B, Nestle FO. TLRs to cytokines: Mechanistic insights from the imiquimod mouse model of psoriasis. Eur J Immunol. 2013;43:3138–3146. doi: 10.1002/eji.201343801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abrahamsen B, et al. The cell and molecular basis of mechanical, cold, and inflammatory pain. Science. 2008;321:702–705. doi: 10.1126/science.1156916. doi:10.1126/science.1156916 321/5889/702 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lumpkin EA, Caterina MJ. Mechanisms of sensory transduction in the skin. Nature. 2007;445:858–865. doi: 10.1038/nature05662. doi:nature05662 [pii] 10.1038/nature05662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sandor K, Helyes Z, Elekes K, Szolcsanyi J. Involvement of capsaicin-sensitive afferents and the Transient Receptor Potential Vanilloid 1 Receptor in xylene-induced nocifensive behaviour and inflammation in the mouse. Neurosci Lett. 2009;451:204–207. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2009.01.016. doi:10.1016/j.neulet.2009.01.016 S0304-3940(09)00043-3 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zheng Y, et al. Interleukin-22, a T(H)17 cytokine, mediates IL-23-induced dermal inflammation and acanthosis. Nature. 2007;445:648–651. doi: 10.1038/nature05505. doi:nature05505 [pii] 10.1038/nature05505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lowes MA, Russell CB, Martin DA, Towne JE, Krueger JG. The IL-23/T17 pathogenic axis in psoriasis is amplified by keratinocyte responses. Trends Immunol. 2013;34:174–181. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2012.11.005. doi:10.1016/j.it.2012.11.005 S1471-4906(12)00199-8 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rapp SR, Feldman SR, Exum ML, Fleischer AB, Jr, Reboussin DM. Psoriasis causes as much disability as other major medical diseases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41:401–407. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(99)70112-x. doi:S0190-9622(99)70112-X [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Farber EM, Lanigan SW, Boer J. The role of cutaneous sensory nerves in the maintenance of psoriasis. Int J Dermatol. 1990;29:418–420. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4362.1990.tb03825.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ostrowski SM, Belkadi A, Loyd CM, Diaconu D, Ward NL. Cutaneous denervation of psoriasiform mouse skin improves acanthosis and inflammation in a sensory neuropeptide-dependent manner. J Invest Dermatol. 2011;131:1530–1538. doi: 10.1038/jid.2011.60. doi:10.1038/jid.2011.60 jid201160 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grebe KM, et al. Sympathetic nervous system control of anti-influenza CD8+ T cell responses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:5300–5305. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808851106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Swirski FK, et al. Identification of Splenic Reservoir Monocytes and Their Deployment to Inflammatory Sites. Science. 2009;325:612–616. doi: 10.1126/science.1175202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Weninger W, et al. Specialized contributions by alpha(1,3)-fucosyltransferase-IV and FucT-VII during leukocyte rolling in dermal microvessels. Immunity. 2000;12:665–676. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80217-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Iannacone M, et al. Subcapsular sinus macrophages prevent CNS invasion on peripheral infection with a neurotropic virus. Nature. 2010;465:1079–1083. doi: 10.1038/nature09118. doi:nature09118 [pii] 10.1038/nature09118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Matloubian M, et al. Lymphocyte egress from thymus and peripheral lymphoid organs is dependent on S1P receptor 1. Nature. 2004;427:355–360. doi: 10.1038/nature02284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gray EE, et al. Deficiency in IL-17-committed Vgamma4(+) gammadelta T cells in a spontaneous Sox13-mutant CD45.1(+) congenic mouse substrain provides protection from dermatitis. Nat Immunol. 2013;14:584–592. doi: 10.1038/ni.2585. doi:10.1038/ni.2585 ni.2585 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pantelyushin S, et al. Rorgammat+ innate lymphocytes and gammadelta T cells initiate psoriasiform plaque formation in mice. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:2252–2256. doi: 10.1172/JCI61862. doi:10.1172/JCI61862 61862 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guo L, Junttila IS, Paul WE. Cytokine-induced cytokine production by conventional and innate lymphoid cells. Trends Immunol. 2012;33:598–606. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2012.07.006. doi:10.1016/j.it.2012.07.006 S1471-4906(12)00128-7 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Awasthi A, et al. Cutting edge: IL-23 receptor gfp reporter mice reveal distinct populations of IL-17-producing cells. J Immunol. 2009;182:5904–5908. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900732. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.0900732 182/10/5904 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Muller G, et al. IL-12 as mediator and adjuvant for the induction of contact sensitivity in vivo. J Immunol. 1995;155:4661–4668. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zigmond E, et al. Ly6C hi monocytes in the inflamed colon give rise to proinflammatory effector cells and migratory antigen-presenting cells. Immunity. 2012;37:1076–1090. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.08.026. doi:10.1016/j.immuni.2012.08.026 S1074-7613(12)00504-3 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Guilliams M, et al. From skin dendritic cells to a simplified classification of human and mouse dendritic cell subsets. Eur J Immunol. 2010;40:2089–2094. doi: 10.1002/eji.201040498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wohn C, et al. Langerinneg conventional dendritic cells produce IL-23 to drive psoriatic plaque formation in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:10723–10728. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1307569110. doi:10.1073/pnas.1307569110 1307569110 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chiu IM, et al. Bacteria activate sensory neurons that modulate pain and inflammation. Nature. 2013 doi: 10.1038/nature12479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lindquist RL, et al. Visualizing dendritic cell networks in vivo. Nat Immunol. 2004;5:1243–1250. doi: 10.1038/ni1139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.De Togni P, et al. Abnormal development of peripheral lymphoid organs in mice deficient in lymphotoxin. Science. 1994;264:703–707. doi: 10.1126/science.8171322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jung S, et al. In vivo depletion of CD11c(+) dendritic cells abrogates priming of CD8(+) T cells by exogenous cell-associated antigens. Immunity. 2002;17:211–220. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00365-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Garcia AD, Doan NB, Imura T, Bush TG, Sofroniew MV. GFAP-expressing progenitors are the principal source of constitutive neurogenesis in adult mouse forebrain. Nature neuroscience. 2004;7:1233–1241. doi: 10.1038/nn1340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Boes M, et al. T-cell engagement of dendritic cells rapidly rearranges MHC class II transport. Nature. 2002;418:983–988. doi: 10.1038/nature01004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Saito M, et al. Diphtheria toxin receptor-mediated conditional and targeted cell ablation in transgenic mice. Nat Biotechnol. 2001;19:746–750. doi: 10.1038/90795. doi:10.1038/9079590795 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.