Abstract

Objective

To review systematically the role of e-mails in patient–provider communication in terms of e-mail content, and perspectives of providers and patients on e-mail communication in health care.

Methods

A systematic review of studies on e-mail communication between patients and health providers in regular health care published from 2000 to 2008.

Results

A total of 24 studies were included in the review. Among these studies, 21 studies examined e-mail communication between patients and providers, and three studies examined the e-mail communication between parents of patients in pediatric primary care and pediatricians. In the content analyses of e-mail messages, topics well represented were medical information exchange, medical condition or update, medication information, and subspecialty evaluation. A number of personal and institutional features were associated with the likelihood of e-mail use between patients and providers. While benefits of e-mails in enhancing communication were recognized by both patients and providers, concerns about confidentiality and security were also expressed.

Conclusion

The e-mail is transforming the relationship between patients and providers. The rigorous exploration of pros and cons of electronic interaction in health care settings will help make e-mail communication a more powerful, mutually beneficial health care provision tool.

Practice implications

It is important to develop an electronic communication system for the clinical practice that can address a range of concerns. More efforts need to be made to educate patients and providers to appropriately and effectively use e-mail for communication.

Keywords: E-mail, Internet, Patient–provider communication, Health care

1. Introduction

Communication is an essential component of patient care. A wealth of evidence has shown that effective communication between providers and patients may positively influence patients’ behaviors and well-being, including satisfaction with care, medication adherence, recall and comprehending of medical information, and functional and physiological status [1–6]. Traditionally, face-to-face communication and telephone communication have been the primary means for the patients to interact with their health providers. However, with advances in technology, Internet applications for communications, particularly electronic mail (e-mail), are emerging as another viable avenue for patient communication. The popularity of e-mail in daily life is attributable to some of its unique characteristics, such as asynchronous communication and rapid message transfer. Despite the simplicity and efficiency of e-mail, the medical profession has been slow in embracing it as a means of improving patient communications [7,8].

According to the American Medical Association, the provider needs to take on an explicit measure of responsibility for the patient's care in provider–patient e-mail. Providers who choose to utilize e-mail for patient and medical practice communications are required to follow the communication, medicolegal, and administrative guidelines [9]. These guidelines apply to electronic communication within an established partnership. Attention is particularly paid to informed consent, confidentiality, and record keeping of e-mail exchanges.

In recent years, with the increasing penetration of the Internet, many studies have been conducted to examine E-communication between providers and patients. This review aimed to improve understanding of the role of e-mail in patient–provider communication. In this report, we assess: (1) the content of e-mail communication between patients and providers; (2) patients’ use of and attitudes toward e-mail communication with providers; and (3) providers’ use of and attitudes toward e-mail communication with patients.

2. Methods

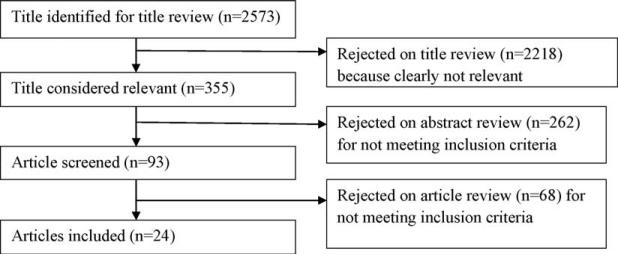

This review was carried out using systematic methods to produce a narrative summary. Relevant studies were identified using a systematic search of the computerized databases including PubMed/MEDLINE, ProQuest, and PsycINFO. The following terms were used, in various combinations, in the search: e-mail, electronic communication, doctor–patient communication, physician–patient communication, patient–doctor communication, patient–physician communication, primary care, health care, family medicine, internal medicine. The inclusion criteria included (1) empirical research focused on at least one aspect of e-mail communication between patients and health providers during the regular health care: provider's perspective, patient's perspective, and/or e-mail content; (2) studies conducted in the United States and were written in English, and (3) studies published between 2000 and 2008. E-mail communication was defined as electronic mails that allow asynchronous transmission of messages by using computer networks. We excluded studies that merely focused on providers’ or patients’ use of information technology in general or other forms of Internet communication tools such as Internet/ instant messengers. A flow diagram (Fig. 1) shows an overview of the study selection.

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of included and excluded studies.

3. Results

A total of 24 studies were included in the review. Among these studies, 21 studies examined patient–provider e-mail communication, and three studies examined the e-mail communication between parents of patients in pediatric primary care and their pediatricians. Most of the studies used cross-sectional surveys that were conducted in different formats, including in-person/paper-based survey, Internet-based/e-mail survey, and mailed survey. Six studies analyzed the content of e-mail messages from both patients and providers. In two studies, in-depth interviews were conducted among patients or providers. Three studies adopted interventions that allowed researchers to test the effects of e-mail use on provider–patients relationships. Table 1 provides the sample and study design of research papers included in the review.

Table 1.

Overview of the studies of E-mail communication between patients and providers.

| Authors | Research objectives | Sample | Methods | Findings related to |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anand et al. [10] | To evaluate the content of e-mails between providers and parents of patients in pediatric primary care, and parent attitudes about e-mail. | Two primary care pediatricians 54 parents of patients e-mails from pediatricians and parents |

1.Content analysis 2.Cross-sectional e-mail survey |

1.E-mail content 2.Patient use and Attitudes 3.Provider use and attitudes |

| Brooks and Menachemi [27] | To examine factors associated with physician-patient e-mail, and report on the physicians' adherence to recognized guidelines for e-mail communication. | 4203 physicians in Florida | Cross-sectional mailed survey | Provider use and attitudes |

| Couchman et al. [16] | To determine the proportion of patients with e-mail access, determine patients' willingness to use this technology to expedite communication with health care providers, and assess their expectations of response times. | 950 patients in 6 family practice clinics | Cross-sectional in-person survey | Patient use and attitudes |

| Couchman et al. [17] | To assess patients' willingness of using e-mail to obtain test results, assess their expectations regarding response times, and identify any demographic trends. | 2314 patients in 19 general clinics | Cross-sectional in-person survey | Patient use and attitudes |

| Gaster et al. [28] | To assess physicians' use of and attitudes toward e-mail for patient communication | 283 physicians who saw patients in outpatient clinics | Cross-sectional mailed survey | Provider use and attitudes |

| Grant et al. [29] | To determine current prevalence of non-electronic health record Internet technology use by a national sample of U.S. physicians, and to identify associated physician, practice, and patient panel characteristics. | 1662 US patients from 3 primary care specialties and 3 nonprimary care specialties | Cross-sectional mailed survey | Provider use and attitudes |

| Hobbs et al. [30] | To evaluate the current use of e-mail between physicians and patients in an integrated delivery system, and to identify developments that may promote increased use of e-mail communication. | 71 primary care physicians n the Partners HealthCare System | Cross-sectional paper-based survey | Provider use and attitudes |

| Houston et al. [31] | To survey the experiences of physicians who were early adopters of the technology, including an assessment of satisfaction with using e-mail with patients. | 204 physicians who reported using e-mail with patients on a daily basis | Cross-sectional Internet-based survey | Provider use and attitudes |

| Houston et al. [18] | To explore the experiences of patients who were early adopters of e-mail communication with their physicians. | 1881 patients who responded to the recruiting message posted on Intelihealth.com | 1.Cross-sectional Internet-base survey 2.In-depth telephone follow-up interview with 56 individuals |

Patient use and attitudes |

| Kagan et al. [32] | To describe surgeons' and nurses' use of e-mail with patients and their caregivers after head and neck cancer surgery. | 423 surgeons and nurses who were members of three professional societies | Cross-sectional mailed survey | Provider use and attitudes |

| Kagan et al. [19] | To describe patients' and family members' interest in and use of e-mail with their surgeons and nurses after head and neck cancer surgery. | 74 patients and 35 family members attending clinic visits after head and neck cancer surgery | Cross-sectional in-person survey | Patient use and attitudes |

| Katz et al. [20] | To test whether a triage-based e-mail system can enhance communication between patients and their providers | 24 staff physicians and 74 resident physicians in internal medicine and family practice (50 in the e-mail group, and 48 in the control group) 900 patients (450 patients of physicians in the intervention group and 450 patients of physicians in the control group) |

Controlled trial Intervention (survey) | 1.Patient use and attitudes 2.Provider use and attitudes |

| Katzen et al. [21] | To evaluate patient interest, assess patient perspectives about how e-mail communication might facilitate medical treatment and advice, and determine areas of patient concern regarding e-mail communication with their physicians. | 47 patients treated for prostate cancer with radiation therapy | Cross-sectional mailed survey | Patient use and attitudes |

| Kleiner et al. [22] | To determine (1) the e-mail capabilities of families, general pediatricians, and subspecialty pediatricians from an integrated pediatric health care delivery system and (2) the knowledge base and attitudes of these groups regarding the potential issues involved in using e-mail for physician-patient communication. | 325 parents of patients and 37 physicians in the office of practices | Face-to-face interview using a standardized survey tool. | 1.Patient use and attitudes 2.Provider use and attitudes |

| Leong et al. [11] | To examine whether e-mail enhance communication and address some of the barriers inherent to medical practices | 100 patients (67 in the e-mail group, and 33 in the control group) | Controlled trial intervention (survey, content analysis) | 1.E-mail content 2.Patient use and attitudes 3.Provider use and attitudes |

| Moyer et al. [23] | To determine e-mail utilization patterns and attitudes toward e-mail use among primary care physicians and their ambulatory outpatient clinic patients. | 476 consecutive outpatient clinic patients, 126 general medical and family practice physicians, and 16 clinical and office staff | Cross-sectional paper-based survey | 1.Patient use and attitudes 2.Provider use and attitudes |

| Patt et al. [33] | To understand physicians' experience of e-mail communication with their patients | 45 physicians currently using e-mail with patients (identified through sample of members of Physicians' Online) | In-depth phone interview | Provider use and attitudes |

| Rosen and Kwoh [12] | To assess the patterns of patient users of a patient-physician e-mail service, measure physician time spent on e-mail communication with patients, and determine the satisfaction of families who are provided e-mail access to their child's rheumatologist. | 306 patient families who were offered patient-physician e-mail access | Intervention (survey and content analysis) | 1.E-mail content 2.Patient use and attitudes |

| Roter et al. [13] | To examine the extent to which e-mail messages between patients and physicians mimic the communication dynamics of traditional medical dialogue and its fulfillment of communication functions. | E-mails from 40 patients and 34 physicians | Content analysis | E-mail content |

| Schiamanna et al. [24] | To assess the access of patients to physicians who conduct e-mail consults. | National representative sample (physicians: n = 825 in 2001; n = 970 in 2002; n = 930 in 2003) | Data from the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NAMCS) in 2001, 2002, and 2003. | 1.Patient use and attitudes 2.Provider use and attitudes |

| Sittig [14] | To provide insight into how patients are using e-mail to request information or services from their healthcare providers. | E-mails from 5 physicians and their patients | Content analysis | E-mail content |

| Sitting et al. [25] | To determine how a group of Internet-active, e-mail-ready patients currently use, or potentially view, the ability to exchange e-mail messages with their health care providers | 954 users of WebMD | Cross-sectional e-mail survey | Patient use and attitudes |

| Virji et al. [26] | To determine the number of clinic patients receptive to communicating with their physician via e-mail and to assess the feasibility of providing health education via e-mail to family practice patients. | 390 patients at a family medicine clinic | Cross-sectional paper-based survey | Patient use and attitudes |

| White et al. [15] | To determine the validity of concerns about patients' inappropriate and inefficient use of the technology. | 3007 patient-physician e-mail messages | Content analysis | E-mail content |

3.1. Content of e-mails

Six studies that used content analysis method examined both the content and feature of e-mails between providers and patients (Table 2) [10–15]. The majority of e-mail inquiries from patients were for nonacute issues, including medical questions, medical condition/consultations/medical update, medication information, and subspecialty evaluation. A smaller number of e-mails were concerned with administrative issues and lab testing results. In studying the message exchanges between patients and physicians. Roter et al. [13] reported that in addition to task-focused communication, the rest of e-mail messages was characterized as expressing and responding to emotions and building a therapeutic partnership. In very rare cases, patients used e-mail for urgent issues. Rosen and Kwoh [12] found that 5.7% of patients’ e-mails were urgent (i.e., notification of disease flare or new symptoms) and only 0.002% of the e-mails required physicians’ emergent attention. Similarly, White et al. [15] found that very few e-mails (5.1%) included sensitive content, and none of them were urgent messages.

Table 2.

Findings on content of e-mails.

| Sources | Main findings |

|---|---|

| Anand et al. [10] | Of all e-mail exchanges, 81 were generated by parents of patients and 91 by pediatricians. E-mail inquiries were all for nonacute issues. The e-mail exchanges resulted in appointments, phone calls, subspecialty referrals, prescriptions or recommendations for over-the-counter medications, administrative tasks, and radiograph. |

| Leong et al. [11] | E-mail messages were about informational content (32%), medical conditions/consult (31%), medication (16%), administrative (14%), and test results (6.7%). The response time was longer with e-mail than with phone; 38% were answered in the same day, 29% in 1 day, and 15.5% in 2 days. |

| Rosen and Kwoh [12] | The patients sent 40% of their e-mails outside business hours. 5.7% of e-mails from the patients communicated urgent concerns. 0.002% of e-mails to the physician required emergent attention. |

| Roter et al. [13] | E-mails sent by physicians were shorter and more direct than those of patients (the number of statements: 7 vs. 14; p < .02 and words 62 vs. 121; p < .02). Majority of statements of physicians (72%) and patients (59%) were devoted to information exchange; other communication included expressing and responding to emotions and building a therapeutic partnership. Many similarities in communication patterns in e-mail and face-to-face interaction. |

| Sittig [14] | On average, replies sent by physicians contained only 39 words and 59.4% of them were sent within 24 hours. Patients averaged 1 request per message. 75% of patients' request focused on information on medications or treatments, specific symptoms or diseases, and requests for actions regarding medications or treatments. Physicians fulfilled 80.2% of patients' requests. |

| White et al. [15] | 82.8% of e-mail messages from the patients addressed a single issue. Frequently used message types included information updates to the physicians (41.4%), prescription renewals (24.2%), health questions (13.2%), questions about test results (10.9%) and referrals (8.8%). 94.5% of messages were directly related to medical issues. Only 5.1% of messages included sensitive content, and none included urgent messages. |

Three studies examined the characteristics of e-mails and indicated that the messages from patients were usually brief, formal, and medically relevant [13–15]. One study also found that most of patient-initiated messages (82.8%) addressed a single issue [15]. Another study that compared physicians’ e-mail with patients’ e-mails showed that physicians’ messages tended to be shorter and more direct than those of patients [13].

3.2. Patients’ use of and attitudes toward e-mail communication with providers

A total of 14 studies examined the e-mail use of patients to communicate with their providers (Table 3) [10–12,16–26]. Studies conducted at a state level or within certain clinics found that only low percentages of patients had ever communicated via e-mail with their providers, even though many patients expressed interests [17,19,23,25]. For instance, Couchman et al. [17]. surveyed 2314 patients in 19 general health clinics, and found that although over half of patients reported having current e-mail access and were willing to use it for communication, only 5.8% reported having ever used it to communicate with their provider.

Table 3.

Findings on patients' use of and attitudes toward e-mail communication with providers.

| Sources | Main findings |

|---|---|

| Anand et al. [10] | Of all the parents who returned survey, 93% were mothers and 86% had completed college. 98% were very satisfied with their e-mail communication with their pediatrician. 80% felt that all pediatricians should use e-mail for communication with parents and 65% would be more likely to choose a pediatrician based on access by e-mail; 63% were unwilling to pay for access. |

| Couchman et al. [16] | 54.3% of patients reported having e-mail access, with significant variation among the clinics involved in the survey. Patients mostly desired to use the e-mail for requesting prescription refills, non-urgent consultations, and obtaining routine laboratory results or test reports. |

| Couchman et al. [17] | 58.3% of patients had e-mail access, but only 5.8% reported having used it to communicate with their physician. Patients were most willing to use e-mail for requesting prescription refills (83%), followed by direct communication with their physician (82%), non-urgent consultations (82%), and obtaining routine laboratory results or test reports (82%). High expectation of timeliness of responses. Significant differences of willingness and expectations by age group, education, and income. |

| Houston et al. [18] | Users of e-mail with physicians in this survey were twice as likely to have a college education, were younger, were less frequently ethnic minorities, and more frequently reported fair/poor health than participants in the population-based Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance Survey (BRFSS). Among those who used e-mail with their physicians, the most common topics were results of laboratory testing and prescription renewals. 21% of topics reported included urgent issues and 17% included sensitive issues. Frequently reported benefits of e-mail communication included the efficiency of communication, being more emboldened to ask questions and able to save the e-mail messages. Users expressed concerns about privacy. |

| Kagan et al. [19] | 9.5% of patients reported actually using e-mail to contact their surgeon or nurses. About 30% of those who were not currently using e-mail with health professionals planned to do so within the coming year. The most common issues addressed by e-mail were symptom management and prescription refills. Family members were less interested in using e-mail than patients. |

| Katz et al. [20] | There were few differences between patients in e-mail group and control group in attitudes toward electronic communication or communication in general. |

| Katzen et al. [21] | Patients favored e-mail for increased convenience, efficiency, and timeliness for communication with their physicians about general health problems. 80% of respondents favored posing a health-related question to their physicians over e-mail. 51% of patients were concerned about overall confidentiality of physician-patient e-mail communication. |

| Kleiner et al. [22] | Parents aged 31–40 years were significantly more likely to have access to e-mail. E-mail access was higher for those with higher family income or higher parental education. 74% parents expressed interest in using e-mail to contact their child's physician/physician's office for getting information or test results, scheduling appointments, and/or discussing a particular symptom. Parents at the general pediatricians offices were significantly more concerned about confidentiality than those at subspecialty pediatricians offices. |

| Leong et al. [11] | Compared with patients in the control group, those in the e-mail group showed higher level of satisfaction the areas of convenience of communicating with their physician and the amount of time spent contacting their physician. |

| Moyer et al. [23] | Among the self-defined e-mail users, only 10.5% of them had ever used e-mail to communicate with their doctors. 70% of all patients said they would be willing to use e-mail to communicate with their doctors. Overall, patients were concerned about logistics (e.g., whether the message would get to the right person, how long it would take to get a response). |

| Rosen and Kwoh [12] | 86% strongly agreed or agreed that e-mail increased access to their children's doctors. 84% strongly agreed or agreed that more physicians should offer e-mails. |

| Schiamanna et al. [24] | The likelihood of access to a provider who did e-mail consults were greater for patients who visited primary care providers, for patients seen in the west, for patients aged 45–64, for male patients, for nonminority patients, for patients seen for pre-postsurgical care, and for those who saw a physician instead of a nurse in addition to a physician. |

| Sittig et al. [25] | 6% of the patients in the survey had actually sent an e-mail message to their provider. Identified main issues that prevented patients from sending e-mail messages to their providers included not knowing their provider's e-mail address and concerns that someone other than their provider may read the message. When being told that their e-mail messages might be read for screening, over 33% patients were worried that their messages could be intercepted and read by unauthorized people. |

| Virji et al. [26] | 80% of patients who used e-mails were interested in using e-mail to communicate with the clinic. 42% were willing to pay an out-of-pocket fee for e-mail access to their physicians. |

Three studies examined the links between the sociodemo-graphic characteristics of patients and their use of e-mail communication with providers [17,18,24]. Couchman et al.'s [17] study showed that patients’ prior use of e-mail with their providers was significantly associated with annual family income and weakly associated with education. Another study using data from an Internet-based survey of 1881 patients found that compared with population-based Behavioral Risk Factor Surveil-lance Survey (BRFSS), users of e-mail with providers were twice as likely to have a college degree, were younger, were less frequently ethnic minorities, and more frequently reported fair/poor health status [18]. Schiamanna et al.'s [24] analyses of national representative data showed that the likelihood of patients’ access to a provider who did e-mail consults were greater for male patients, for patients aged 45–64, for nonminority patients, for patients seen for pre-postsurgical care, and for those who saw a physician instead of a nurse in addition to a physician.

Benefits of using e-mail for communicating with providers included convenience [11,21], increased access to the provider [12], improved the quality of care [12,21], feeling more comfortable to ask questions [18], and the ability to save the message [18]. Barriers to using e-mails with providers were highlighted in three studies. Moyer et al.'s [23] study indicated that patients were concerned about logistic issues, such as whether the message would get to the right person and how long it would take to get a response. In Sittig et al.'s [25] study, over two thirds of patients cited not having their providers’ e-mail address as a main reason for not sending e-mail to providers; over one-fifth expressed concerns that someone other than their health care providers would read their message. In Houston et al.'s [18] study, e-mail users also expressed concerns about privacy when e-mailing their providers.

Interventional studies that tested attitudes of patients toward e-mail communication with their providers yielded inconsistent results. Two studies showed that providing e-mail communication for patients may increase patients’ satisfaction with communication and health care quality. In Leong et al.'s [11] intervention, 4 physicians offered e-mail communication to participating patients and 4 did not. Patient satisfaction sig nificantly increased in the e-mail group compared with the control group in the areas of convenience and the amount of time spent interacting with their physicians. In Rosen and Kwoh's [12] study, a consecutive series of patients’ families were offered e-mail access during a 2-year period. After 1 year of enrollment in the patient–physician e-mail service, the majority of families agreed that patient–physician e-mail increased access to the physician and improved the quality of care. However, the intervention study conducted by Katz et al. [20] that tested the effect of a triage-based e-mail system showed that patients in the intervention group that had access to the e-mail system did not have more favorable attitudes toward electronic communication or communication in general than patients in the control group that did not have access to the system.

3.3. Providers’ use of and attitudes toward e-mail communication with patients

Of all the studies included in the review, 13 studies examined some aspects of providers’ e-mail communication with patients (Table 4) [10,11,20,22–24,27–33]. The reported percentage of providers who had ever used e-mail to communicate with their patients varied substantially across studies. Gaster et al. [28] found that among 283 providers who saw patients in outpatient clinics, 72% of providers reported using e-mail to communicate with patients, averaging 7.7 e-mails from patients per month. However, Brooks and Menachemi [27] found that among 4203 providers who returned questionnaires, 16.6% had personally used e-mail to communicate with patients and only 2.9% used e-mail with patients frequently. In addition, only 6.7% of the providers in their study adhered to at least half of the 13 selected guidelines for e-mail communication. Schiamanna et al.'s [24] study using the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey showed that overall, 6.9% of patient visits in the United States were with a provider who conducted Internet or e-mail consults (9.2% in 2001, 5.8% in 2002, and 5.5% in 2003).

Table 4.

Findings on providers' use of and attitudes toward e-mail communication with patients.

| Sources | Main findings |

|---|---|

| Anand et al. [10] | During 6-week period, the 2 pediatricians estimated an average of 30min/day spent responding to e-mail. |

| Brooks and Menachemi [27] | Of the physicians who returned the survey, 16.6% had used e-mail to communicate with patients. Only 2.9% used e-mail with patients frequently. Univariate analysis showed that e-mail use correlated with physician age (decreased use: age > 61), race (decreased use: Asian background), medical training (increased use: family medicine or surgical specialty), practice size (increased use: >50 physicians), and geographic location (increased use: urban). In a multivariate model, practice size greater than 50 and Asian-American race were related to e-mail use with patients. Only 6.7% physicians adhered to at least half of the 13 selected guidelines for e-mail communication. |

| Gaster et al. [28] | 72% of physicians used e-mail to communicate with patients. Significant differences were observed by practice site, with lowest use by community-based primary care physicians. Those who had used e-mail with patients were highly satisfied with its use. Physicians were concerned about the confidentiality of e-mail. |

| Grant et al. [29] | 3.4% of physicians surveyed reported frequent use e-mail communication with patients. Primary care practice and academic practice setting were strongly associated with use of information technology, including e-mail with patients. Clinicians graduated from U.S. or Canadian medical school were more likely to communicate with patients and other clinicians via e-mail than those from a foreign medical school. Years since medical school graduation and solo/2-person practice setting were negatively associated with use of information technology. |

| Hobbs et al. [30] | Nearly 75% of physicians used e-mail with their patients. The physicians spent much more time managing patient phone calls than responding to e-mails. The main barriers were workload, security and payment. |

| Houston et al. [31] | Among the frequent users, commonly reported e-mail topics were new, non-urgent symptoms, and questions about lab results. 25% were not satisfied with physician-patient e-mail. Important reasons for using e-mail with patients among satisfied physicians included time saving and helping deliver better care. Dissatisfied physicians were concerned about time demands, medicolegal risks, and ability of patients to use e-mail appropriately. |

| Kagan et al. [32] | 40 and 25% of surgeons and nurses, respectively, used e-mail with patients. More than half of both clinician groups that used e-mail with patients began this practice at the request of patients. Surgeons not using e-mail with patients were more likely than nurses to cite concerns about privacy, liability issues, time management, and miscommunication. |

| Katz et al. [20] | E-mail volume was greater for intervention physicians than control physicians. Physicians in the e-mail intervention group reported more favorable attitudes toward electronic communication than did control physicians. |

| Kleiner et al. [22] | 74% of general pediatricians and 100% of subspecialty pediatricians had access to e-mail. 79% of them did not want to use e-mail for physician-patient communication, with concerns about confidentiality and time demands. |

| Leong et al. [11] | Physicians in the e-mail group increased their satisfaction of the e-mail message system regarding convenience, amount of time spent on messages, and volume of messages. The response time was longer with e-mail than phone messages. |

| Moyer et al. [23] | 61.1% of physicians felt that e-mail was a good way for patients to reach them and helping them handle patients' administrative concerns. Frequent e-mail users had more favorable attitudes toward using e-mail with patients. Physicians and staff were more optimistic than patients about using e-mail to improve the doctor-patient relationship. |

| Patt et al. [33] | The dominant and consistent theme was that e-mail communication enhanced chronic-disease management. Many physicians reported improved continuous communication with patients and increased flexibility in responding to non-urgent issues by using e-mail. |

| Schiamanna et al. [24] | 9.2% of outpatient visits in the United States in 2001, 5.8% in 2002, and 5.5% in 2003 were to physicians who conducted Internet or e-mail consults. |

Providers’ e-mail use with patients was higher for primary care physicians (as compared to specialty care physicians) [24], those in the west [24], those in larger practices [27], those graduated from American or Canadian medical schools [29], and those in academic practice settings [29], but was lower for providers of Asian-American race [27] and for those in community-based primary care setting (as compared to hospital-based sites) [28]. While studies found some providers were satisfied with using e-mails with patients because it was convenient [11,31,33] and helped improve health care [23,31,33], providers also identified a number of barriers to their use of e-mail communication with patients. The most commonly expressed barriers were workload and time demands [22,30–33], confidentiality and security [22,30–32], lack of reimbursement [30,33], and inappropriate use of e-mail by patients [23,31–33].

4. Discussion and conclusion

4.1. Discussion

With the further penetration of information technology in the past decade, there is a growing body of literature regarding electronic communication between providers and patients. This systematic review identified 24 studies that focused on certain aspects of e-mail communication in health care. Because of heterogeneity of study design, outcome measures and other methodological features, the results were presented descriptively, focusing on e-mail content and features, patients’ perspectives, and providers’ perspectives.

In the content analysis of e-mail messages, topics that were well represented included medical information exchange, medical condition or update, medication information, subspecialty evaluation. The content and tone of the majority of e-mails were appropriate. Patients in these studies who sent e-mail generally wrote medically focused content, limited the number of requests to one per message, and avoided urgent requests or sensitive health issues.

The use of e-mail in health care increased among certain groups of patients and providers. Some data have suggested that among patients, e-mail use was associated with gender, age, education, ethnicity, living areas, family income, and health status; among providers, e-mail use was related to ethnicity, physician specialty, geographic region of their office, areas of medical schools attended, practice size, and settings. However, the evidence was based on a very limited number of studies—three studies for patent characteristics [17,18,24] and four studies for provider characteristics [24,27–29]. More investigation on factors related to use of e-mail for health care communication is warranted.

The benefits of e-mails were recognized by both patients and providers. One implication that most studies made is that the e-mail has great potential to improve health care communication between providers and patients, thus increasing satisfaction and the quality of care. It is important to note that patients and providers shared concerns in using e-mails for communication security and privacy. In clinical settings, providers have ethical and legal obligations to maintain the privacy and confidentiality of their communications with and regarding patients. E-mail communication between patients and providers adds complexity and responsibilities for both parties. Risks to patient confidentiality can occur in such situations as when multiple individuals share the same e-mail address, or when access passwords are not used or are not kept secured [34]. Providers also had concerns about workload and time demands, as they spent valuable time and resources responding to patients’ e-mail messages.

Some solutions to these concerns have been suggested in previous articles. For example, a secure server can be developed for online communication between patients and providers. The provider's office must first authenticate the identity of the patient, and provide a sign-on code and temporary password specific to that individual. The patients can reset their password after they first log in. A message alert will be sent to patients’ home e-mail address when a message is sent to that patient's system mailbox by the office [34]. An integrated web system may also have functions that can prevent providers from being overwhelmed by e-mails, such as limiting the e-mail to a certain number of characters. Compared to regular e-mails, such a web system may be safer and less time-consuming. Some healthcare delivery systems have adopted secure web-based portals to facilitate electronic communication between patients and providers [35]. It is important to develop plans that compensate providers for time spent communicating via e-mail with patients. This may substantially increase their willingness to adopt this service, which further lead to better health care delivery [30].

The studies reviewed were subject to methodology limitations. Some studies that used survey design had rather low response rates. For example, the response rates for Brooks and Menachemi's [27] study and Grant et al.'s [29] study were 28.2% and 52.5%, respectively. The self-selection of participants in studies also limited the generalizability of the results. Very few studies used a controlled trial design. Thus, it is hard to determine the extent to which e-mail use may influence provider–patient communication and relationship and the health outcome of patients.

4.2. Conclusion

There are several implications of this review for future research, policy and practice. Efforts need to be made in disseminating formal guidelines regarding e-mail use to ensure that providers and patients effectively use e-mail for health care communication, while being fully aware of possible risks. Future studies need to examine how the e-mail communication between providers and patients may influence patients’ health outcome, such as adherence with medications and health care costs. It may also be necessary to explore links between e-mail use and providers’ prior and subsequent malpractice rates. Providers’ willingness to adopt e-mail in health care may be associated whether the use of e-mail communication with their patients will improve outcomes clinically and medicolegally or will leave them more vulnerable since putting information into writing would be more difficult for either party to dispute.

Medical research scholars have predicted that the e-mail use will most likely continue to grow in clinical settings [36]. Even though for many of us e-mail has been a primary means to build relationships and keep in touch in our daily life, it is still a new frontier in patient– provider communication. It has the potential to transform the relationships between providers and patients. E-mail also helps address some unmet needs for communication in health care. The rigorous exploration of various pros and cons of electronic interaction in health care settings will help make e-mail communication a more powerful, mutually beneficial health care provision tool.

4.3. Practice implications

It is important to develop an electronic communication system for the clinical practice that can address a range of concerns. In particularly, the system needs to be tailored to the need of patients and ensure privacy and security. Meanwhile, more efforts need to be made to educate patients and providers to appropriately and effectively use e-mail for communication. Finally, standardized regulations and guidelines should be available for providers to deal with issues on service compensations and any potential ethical problems.

References

- 1.Stewart MA. Effective physician–patient communication and health outcomes: a review. CMAJ-Can Med Assoc J. 1995;152:1423–33. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Levinson W, Roter DL, Mullooly JP, Dull VT, Frankel RM. Physician–patient communication: the relationship with malpractice claims among primary care physicians and surgeons. J Am Med Assoc. 1997;277:553–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.277.7.553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ruiz-Moral R, Pérez Rodríguez E, Pérula de Torres LA, de la Torre J. Physician–patient communication: a study on the observed behaviours of specialty physicians and the way their patients perceive them. Patient Educ Couns. 2006;64:242–8. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2006.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zandbelt LC, Smets EM, Oort FJ, Godfried MH, de Haes HC. Patient participation in the medical specialist encounter: does physicians’ patient-centered communication matter? Patient Educ Couns. 2007;65:396–406. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2006.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dutta-Bergman MJ. The relation between health-orientation, provider–patient communication, and satisfaction: an individual-difference approach. Health Commun. 2005;8:291–303. doi: 10.1207/s15327027hc1803_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kerse N, Buetow S, Mainous AG, Young G, Coster G, Arroll B. Physician–patient relationship and medication compliance: a primary care investigation. Ann Fam Med. 2004;2:455–61. doi: 10.1370/afm.139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bodenheimer T, Grumbach K. Electronic technology: a spark to revitalize primary care. J Am Med Assoc. 2003;290:259–64. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.2.259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Masters K. For what purpose and reasons do doctors use the Internet: a systematic review. Int J Med Inform. 2008;77:4–16. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2006.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.American Medical Association. [July 12, 2009];Guidelines for physician–patient electronic communication. Available at http://www.ama-assn.org/ama/pub/about-ama/our-people/member-groups-sections/young-physicians-section/advocacy-resources/guidelines-physician-patient-electronic-communications.shtml.

- 10.Anand SG, Feldman MJ, Geller DS, Bisbee A, Bauchner HA. Content analysis of e-mail communication between primary care providers and parents. Pediatrics. 2005;115:1283–8. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-1297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Leong SL, Gingrich D, Lewis PR, Mauger DT, George JH. Enhancing doctor–patient communication using email: a pilot study. J Am Board Fam Pract. 2005;18:180–8. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.18.3.180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rosen P, Kwoh CK. Patient–physician e-mail: an opportunity to transform pediatric health care delivery. Pediatrics. 2007;120:701–6. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-1094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Roter DL, Larson S, Sands DZ, Ford DE, Houston T. Can e-mail messages between patients and physicians be patient-centered? Health Commun. 2008;23:80–6. doi: 10.1080/10410230701807295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sittig DF. Results of a content analysis of electronic messages (email) sent between patients and their physicians. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2003;3:11. doi: 10.1186/1472-6947-3-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.White CB, Moyer CA, Stern DT, Katz SJ. A content analysis of e-mail communication between patients and their providers: patients get the message. J Am Med Inform Assn. 2004;11:260–7. doi: 10.1197/jamia.M1445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Couchman GR, Forjuoh SN, Rascoe TG. E-mail communications in family practice: what do patients expect? J Fam Pract. 2001;50:414–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Couchman GR, Forjuoh SN, Rascoe TG, Reis MD, Koehler B, Walsum KL. E-mail communications in primary care: what patients’ expectations for specific test results? Int J Med Inform. 2005;74:21–30. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2004.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Houston TK, Sands DZ, Jenckes MW, Ford DE. Experiences of patients who were early adopters of electronic communication with their physician: satisfaction, benefits, and concerns. Am J Manag Care. 2004;10:601–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kagan SH, Clarke SP, Happ MB. Head and neck cancer patient and family member interest in and use of E-mail to communicate with clinicians. Head Neck. 2005;27:976–81. doi: 10.1002/hed.20263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Katz SJ, Moyer CA, Cox DT, Stern DT. Effect of a triage-based E-mail system on clinic resource use and patient and physician satisfaction in primary care: a randomized controlled trial. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18:736–44. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2003.20756.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Katzen C, Solan MJ, Dicker AP. E-mail and oncology: a survey of radiation oncology patients and their attitudes to a new generation of health communication. Prostate Cancer P D. 2005;8:189–93. doi: 10.1038/sj.pcan.4500797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kleiner KD, Akers R, Burke BL, Werner EJ. Parent and physician attitudes regarding electronic communication in pediatric practices. Pediatrics. 2002;109:740–4. doi: 10.1542/peds.109.5.740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moyer CA, Stern DT, Dodias KS, Cox DT, Katz SJ. Bridging the electronic divide: patient and provider perspectives on e-mail communication in primary care. Am J Manag Care. 2002;8:427–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schiamanna CN, Rogers ML, Shenassa ED, Houston TK. Patient access to U.S. physicians who conduct Internet or E-mail consults. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22:378–81. doi: 10.1007/s11606-006-0076-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sittig DF, King S, Hazlehurst BL. A survey of patient–provider e-mail communication: what do patients think. Int J Med Inform. 2001;61:71–80. doi: 10.1016/s1386-5056(00)00134-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Virji A, Yarnall KS, Krause KM, Pollak KI, Scannell MA, Gradison M, et al. Use of email in family practice setting: opportunities and challenges in patient- and physician-initiated communication. BMC Med. 2006;4:18. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-4-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brooks RG, Menachemi N. Physicians’ use of email with patients: factors influencing electronic communication and adherence to best practices. J Med Internet Res. 2006;8:e2. doi: 10.2196/jmir.8.1.e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gaster B, Knight CL, DeWitt DE, Sheffield JV, Assefi NP, Buchwald D. Physicians’ use of and attitudes toward electronic mail for patient communication. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18:385–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2003.20627.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Grant RW, Campbell EG, Gruen RL, Ferris TG, Blumenthal D. Prevalence of basic information technology use by U.S. physicians. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:1150–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00571.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hobbs J, Wald J, Jagannath YS, Kittler A, Pizziferri L, Volk LA, et al. Opportunities to enhance patient and physician e-mail contact. Int J Med Inform. 2003;70:1–9. doi: 10.1016/s1386-5056(03)00007-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Houston TK, Sands DZ, Nash Br, Ford DE. Experiences of physicians who frequently use e-mail with patients. Health Commun. 2003;15:515–25. doi: 10.1207/S15327027HC1504_08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kagan SH, Clarke SP, Happ MB. Surgeons’ and nurses’ use of e-mail communication with head and neck cancer patients. Head Neck. 2005;27:108–13. doi: 10.1002/hed.20119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Patt MR, Houston TK, Jenckes MW, Sands DZ, Ford DE. Doctors who are using e-mail with their patients: a qualitative exploration. J Med Internet Res. 2003;5:e9. doi: 10.2196/jmir.5.2.e9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gerstle RS. Task Force on Medical Informatics. E-mail communication between pediatricians and their patients. Pediatrics. 2004;114:317–21. doi: 10.1542/peds.114.1.317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kittler AF, Carlson GL, Harris C, Lippincott M, Pizziferri L, Volk LA, et al. Primary care physicians attitudes towards using a secure web-based portal designed to facilitate electronic communication with patients. Inform Prim Care. 2004;12:129–38. doi: 10.14236/jhi.v12i3.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mandl KD, Kohane IS, Brandt AM. Electronic patient–physician communication: problems and promise. Ann Intern Med. 1998;129:495–500. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-129-6-199809150-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]