Abstract

Objective

Individuals with both physical and mental health problems may have elevated levels of emergency department (ED) service utilization either for index conditions or for associated comorbidities. This study examines the use of ED services by Medicaid beneficiaries with comorbid diabetes and schizophrenia, a dyad with particularly high levels of clinical complexity.

Methods

Retrospective cohort analysis of claims data for Medicaid beneficiaries with both schizophrenia and diabetes from fourteen Southern states was compared with patients with diabetes only, schizophrenia only, and patients with any diagnosis other than schizophrenia and diabetes. Key outcome variables for individuals with comorbid schizophrenia and diabetes were ED visits for diabetes, mental health-related conditions, and other causes.

Results

Medicaid patients with comorbid diabetes and schizophrenia had an average number of 7.5 ED visits per year, compared to the sample Medicaid population with neither diabetes nor schizophrenia (1.9 ED visits per year), diabetes only (4.7 ED visits per year), and schizophrenia only (5.3 ED visits per year). Greater numbers of comorbidities (over and above diabetes and schizophrenia) were associated with substantial increases in diabetes-related, mental health-related and all-cause ED visits. Most ED visits in all patients, but especially in patients with more comorbidities, were for causes other than diabetes or mental health-related conditions.

Conclusion

Most ED utilization by individuals with diabetes and schizophrenia is for increasing numbers of comorbidities rather than the index conditions. Improving care in this population will require management of both index conditions as well as comorbid ones.

Keywords: Schizophrenia, Diabetes, Emergency department utilization, Medicaid

1. Introduction

In recent years, there has been increasing focus on improving health outcomes for complex patients with multiple, comorbid, chronic diseases. The US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) has developed a national strategy for improving the health of individuals with multiple chronic conditions (Parekh et al., 2011). Specific combinations of comorbid conditions create unique challenges to the overall health and mortality risk of patients with multiple chronic conditions, particularly comorbid physical and mental illnesses. Morbidity and mortality in individuals with serious mental illness have been well documented, with rates of excess mortality ranging from 8 years to 25 years (Colton and Manderscheid, 2006; Parks et al., 2006; Druss et al., 2011). This excess mortality is attributed most often to chronic physical conditions, and complicated by quality of care and socioeconomic status (Colton and Manderscheid, 2006; Parks et al., 2006; Druss et al., 2011).

There is a strong association with schizophrenia, diabetes, and an increased risk or poor physical health and disability (Dixon et al., 2000). Prevalence rates of diabetes mellitus in patients with schizophrenia are estimated at approximately 15%–21% in previous studies, about two to four times greater than the general population (Dixon et al., 2000; Subramaniam et al., 2003; Bushe and Holt, 2004; Mai et al., 2011). The concurrence of both conditions makes health management complex due to the negative effects on medication adherence for physical illnesses (Piette et al., 2007) and self-care management (Dickerson et al., 2005). In addition, hereditary factors, lifestyle factors, downward social drift, and metabolic syndrome associated with atypical antipsychotic use further contribute to the combined complexity and poor health and social outcomes associated with these diseases (Mukherjee et al., 1996).

Emergency department (ED) visits for mental health-related causes have been rising in recent years, and are responsible for significant burden of care for EDs (Larkin et al., 2005). This increase in visits contributes to ED overcrowding, which can result in poor quality of care (American College of Emergency Physicians, 2008). Mental illness and psychological distress have been associated with higher rates of all-cause ED visits among various populations (Fogarty et al., 2008; Lin et al., 2012). With the rise in mental health-related ED visits each year, higher rates of ED utilization have been associated with psychosis, African American race/ethnicity, and being insured with Medicaid, although these findings are not always consistent (Hazlett et al., 2004; Pandya et al., 2009).

There is limited research on ED utilization among individuals with serious mental illness, and schizophrenia in particular; however, previous reports have shown increased rates of ED utilization for individuals with serious mental illness when compared to the general population (Dickerson et al., 2003; Hackman et al., 2006; Hendrie et al., 2013). Among individuals with schizophrenia, rates of ED utilization and recurrent ED visits are more common when compared to patients who do not have schizophrenia, with 69% of the study population with a diagnosis of schizophrenia having at least one ED visit in two years (Dhossche and Ghani, 1998; Salsberry et al., 2005).

In patients with schizophrenia, certain comorbidities have been associated with increased ED visits, including substance use disorders (Curran et al., 2003). Furthermore, individuals treated with atypical antipsychotic medications have lower rates of ED utilization than individuals treated with typical antipsychotics (Al-Zakwani et al., 2003).

Although few studies have examined ED utilization rates in the chronic comorbid conditions of schizophrenia and diabetes, analysis of chronic physical illness and comorbid serious mental illness (depression) found higher rates of utilization among those with a diagnosis of depression (Himelhoch et al., 2004). Previous studies have examined the impact of schizophrenia with other chronic physical conditions, a study in Canada found that individuals with schizophrenia have greater rates of coronary artery disease, although they are less likely to visit a specialist or undergo coronary revascularization than individuals without schizophrenia (Bresee et al., 2012). In examining the management of diabetes in individuals with schizophrenia, one study determined that people with schizophrenia and diabetes had a 74% greater risk of hospital and ED visits for hypo- or hyperglycemia compared to those with diabetes only (no schizophrenia) (Becker and Hux, 2011). Similarly, individuals with diabetes have higher rates of ED utilization than those without diabetes, but these findings are inconsistent (McCusker et al., 2000; Egede, 2004). Access to a primary care physician is associated with a lower risk of ED utilization for conditions of lower severity (Moineddin et al., 2011). We were unable to find studies that classified the type of ED visit among individuals with schizophrenia and diabetes.

Therefore, because there is a dearth of consistent literature on ED utilization for the specific comorbidity of schizophrenia and diabetes, we undertook this study to evaluate overall ED utilization rates and the causes of ED visits for patients with schizophrenia with and without comorbid diabetes. Also, we evaluated the risk associated with varying types of ED visits in patients with comorbid diabetes and schizophrenia. Because schizophrenia and diabetes can commonly co-occur, and comorbid chronic disease is of great concern in focusing on whole-person outcomes, we seek to better understand the reasons why patients with schizophrenia and diabetes access ED services. A greater understanding of ED utilization in this specific comorbid population can lead to specific, targeted interventions that can improve health outcomes in this multiple chronic conditions population.

2. Materials and methods

This study used claims data extracted from the 2006 and 2007 Medicaid Analytic Extract (MAX) files obtained from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). Secondary data analysis of large population claims data provides several key advantages when studying patients with multiple chronic conditions. First, using Medicaid claims data allows for evaluation of illnesses in a large population, which improves statistical power to address service use patterns related to comorbidity. Second, because Medicaid is provided for aged, blind, disabled segments of low income populations, it can be used to address quality and access to care in vulnerable individuals. Finally, analysis of comorbid conditions in this particular population is important, as the prevalence of this particular study population could increase in the coming years with planned Medicaid expansion under the Affordable Care Act.

2.1. Study population

2.1.1. Inclusion and exclusion criteria

From the Medicaid personal summary file, we identified adults ages 18 to 64 years residing in the states of Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maryland, Mississippi, Missouri, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, and Virginia during the years of 2006 and 2007 (n = 8 376 324). Patients with both Medicaid and Medicare (dual eligible) (n = 2 732 637) or those who participated in a Medicaid Health Maintenance Organization (HMO) plan (n = 1 364 422) were excluded because the necessary encounter-level data could not be reliably accessed from our dataset.

For the purposes of this study, patients were categorized into the following four groups: a) patients with diabetes and without schizophrenia (diabetes only), b) patients with schizophrenia and without diabetes (schizophrenia only), c) patients with both schizophrenia and diabetes, and d) patients with any diagnosis other than schizophrenia or diabetes (neither schizophrenia nor diabetes). Patients that were categorized into these four groups had a varied number of additional co-morbid conditions, ranging from none to greater than nine. Claims related to diabetes were defined as claims billed with primary or secondary diagnosis using International Classification of Diseases 9 (ICD-9) diagnostic codes 250.××, 357.2×, 362.0 or 366.41 (diabetes mellitus and diseases that are complications of diabetes mellitus). Patients with schizophrenia were defined as claims billed with ICD-9 diagnostic codes 295.××. Consistent with previous Medicaid claims data research, in order to improve case-finding accuracy, a person was included in each group according to the specific diagnosis or diagnoses if they had one billed claim for a hospitalization from the inpatient (IP) file, or at least two billed claims on different service dates from the outpatient (OT) file (Lurie et al., 1992). Patients categorized as “neither schizophrenia nor diabetes” were defined as those patients that did not have a primary diagnosis of diabetes or schizophrenia in the IP file, and did not have at least two diagnoses of schizophrenia or diabetes in the OT file.

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Outcome variables

ED visits were divided into the following three categories: a) ED visits resulting from a primary diagnosis of diabetes (diabetes-related ED visits), b) ED visits resulting from a primary mental health diagnosis (mental health-related ED visits), and c) ED visits for all other medical diagnoses (all other-cause ED visits). Mental health diagnoses included all encounters with ICD-9 primary diagnostic codes 290.××–298.×× (psychoses), 300.×× (neurotic disorders), 303.××–305.×× (psychoactive substance), and 308.××–316.×× (other (primarily adult onset) and mental disorders diagnosed in childhood). ED visits were identified by revenue codes 450–459 or a place of service code of 23.

2.2.2. Covariates

Covariates included demographic variables (age, gender, and race/ethnicity), rural/urban status, and comorbidities. Rural/urban status was determined by merging the MAX data with county level data from the Area Resource File (ARF). The ARF aggregates publically available data from multiple sources about socioeconomic and environmental characteristics. Federal Information Processing Standard (FIPS) codes for patient's county of residence were used to merge the ARF and MAX files. The 2003 Rural/Urban Continuum Codes are from the Department of Agriculture's Economic Research Service (ERS) (population < 250 000, population between 250 000 and 1 million, population > 1 million). Comorbidities were characterized using the Elixhauser comorbidity index, a validated approach for risk adjustment using administrative claims data (Elixhauser et al., 1998; Southern et al., 2004). We then classified the comorbidity index into five groups (0, 1–3, 4–5, 6–8, ≥9). The number of disease constructs was tallied for each patient.

2.3. Statistical analysis

We used SAS version 9.2 for all analysis (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). ED visits per 1000 patients per year by predictor variables were calculated for each of the three ED visit outcomes. One-way analysis of variance tests (ANOVA) were used to evaluate mean differences within the predictor variables for each of the three ED visit outcomes, controlling for the four disease conditions. Multivariate logistic regression models were used to estimate three ED visit risks for the schizophrenia and diabetes conceptual model only, mutually adjusting for age, race/ethnicity, gender, and rural/urban status. P-values < .01 were considered statistically significant.

2.4. Ethics

The study was conducted with approval from the Morehouse School of Medicine Institutional Review Board.

3. Results

3.1. Emergency department visits characterized by disease condition

Table 1 describes ED use by disease conditions: diabetes only (n = 316 873), schizophrenia only (n = 82 326), both schizophrenia and diabetes (n = 23 913), and neither schizophrenia nor diabetes (n = 3 856 153). Half of patients with any disease had ED visits during the time period, but there were higher percentages of ED visits for people with comorbid diabetes and schizophrenia than other disease conditions. Patients with comorbid diabetes and schizophrenia had a significantly higher average number of ED visits per year compared to individuals with neither diabetes nor schizophrenia, diabetes only, or schizophrenia only (p < .01).

Table 1.

Average and total numbers of emergency department visits characterized by disease states.

| Diabetes and schizophrenia | Diabetes only | Schizophrenia only | Neither diabetes nor schizophrenia | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N(%) | 23913 (0.6) | 316873 (7.4) | 82326 (1.9) | 3856153 (90.1) | 4279265 (100) |

| Total ED visits (%)a | 19494 (81.5) | 243115 ( 76.7) | 61581 (74.8) | 1928403 (50.0) | 2252593 (52.6) |

| Mean ED visits/year (sd)a | 7.5 (8.1) | 4.7 (4.4) | 5.3 (6.2) | 1.9 (2.4) | 2.2 (2.8) |

| Diabetes-related ED visits (%)a | 3972 (16.6) | 46251 (14.6) | 113 (0.1) | 1312 (0.0) | 51648 (1.2) |

| Mean diabetes-related ED visits/year (sd)a | 0.3 (0.7) | 0.2 (0.5) | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.0 (0.2) |

| Mental health-related ED visits (%)a | 5616 (23.5) | 14918 (4.7) | 20316 (24.7) | 104444 (2.7) | 145292 (3.4) |

| Mean Mental health-related ED visits/year (sd)a | 0.4 (1.0) | 0.1 (0.3) | 0.4 (0.8) | 0.1 (0.2) | 0.1 (0.2) |

| All other cause ED visits (%) | 19166 (80.2) | 239882 (75.7) | 60442 (73.4) | 1922533 (49.9) | 2242023 (52.4) |

| Mean all other cause visits/year (sd)a | 6.9 (7.6) | 4.4(4.1) | 4.9 (5.9) | 1.8 (2.3) | 2.1 (2.7) |

p < .01.

3.2. Causes of ED visits and demographic characteristics for Medicaid beneficiaries with comorbid diabetes and schizophrenia

Table 2 summarizes ED visits causes for the 23 913 Medicaid beneficiaries with comorbid diabetes and schizophrenia by demographic characteristics. Among these individuals with comorbid diabetes and schizophrenia, there were more mental health-related and other cause visits per 1000 persons per year for younger patients, patients living in urban areas, patients treated with atypical antipsychotics, and patients with greater comorbidities (p < 0.01). Blacks had greater ED visits per 1000 persons per year than whites and Hispanics for diabetes-related visits, but whites had higher rates of ED visits for mental health-related and all other cause visits than black or Hispanic populations (p < 0.01). Asians had significantly lower amounts of all other cause visits compared to other racial groups. There were no significant differences between males and females in rates of mental health-related or diabetes-related ED visits, but females had significantly higher rates of all other cause ED visits compared to males.

Table 2.

Demographics and ED visit causes per 1000 persons/year for patients with diabetes and schizophrenia.

| Diabetes and schizophrenia patients | Diabetes related ED visits |

Mental health related ED visits |

All other cause ED visits |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | p | n (%) | p | n (%) | p | |

| Age | ||||||

| 18-29 (n = 1565) | 277 (17.7) | <.01 | 552 (35.3) | <.01 | 1314 (84.0) | <0.01 |

| 30-44 (n = 6138) | 1108 (18.1) | 1763 (28.7) | 5019 (81.8) | |||

| 45-64 (n = 16 210) | 2587 (16.0) | 3301 (20.4) | 12 833 (79.2) | |||

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||

| White (n = 8987) | 1403 (156) | <.01 | 2455 (27.3) | <.01 | 7374 (82.1) | <.01 |

| Black (n = 10 413) | 1957 (18.9) | 2363 (27.3) | 8375 (80.4) | |||

| Hispanic (n = 2455) | 281 (11.5) | 415 (16.9) | 1828 (74.5) | |||

| Asian (n = 131) | 18 (13.7) | 26 (19.9) | 87 (66.4) | |||

| Other (n = 1927) | 313 (16.2) | 357 (18.5) | 1502 (77.9) | |||

| Gender | ||||||

| Female (n = 15 464) | 2613 (16.9) | 0.11 | 3705 (24.0) | 0.02 | 12836 (83.0) | <.01 |

| Male (n = 8448) | 1359 (16.1) | 1911 (22.6) | 6329 (74.9) | |||

| Rural/urban status | ||||||

| >1 million (metro area) (n = 6528) | 1145 (17.5) | .01 | 1737 (26.6) | <.01 | 5316 (81.4) | <.01 |

| 250 000-1 million (small metro area) (n = 8204) | 1376 (16.8) | 1898 (23 1) | 6568 (80.1) | |||

| <250 000 (rural area) (n = 9181) | 1451 (15.8) | 1981 (21.6) | 7282 (79.3) | |||

| Treatment | ||||||

| Atypical antipsychotics (n = 13910) | 2155 (15.5) | <.01 | 2813 (20.2) | <.01 | 10918 (78.5) | <.01 |

| Typical antipsychotics (n = 1843) | 294 (16.0) | 253 (13.7) | 1327 (72.0) | |||

| Both (n = 6188) | 1149 (18.6) | 2214 (35.8) | 5295 (85.6) | |||

| None (n = 1972) | 374 (19.0) | 336 (17.0) | 1626 (82.5) | |||

| Elixhauser comorbidity index | ||||||

| 0 (n = 6362) | 562 (8.8) | <.01 | 548 (8.6) | <.01 | 3738 (58.8) | <.01 |

| 1-3 (n = 4316) | 637 (14.8) | 753 (17.5) | 3384 (78.4) | |||

| 4-5 (n = 2010) | 311 (15.5) | 458 (22.8) | 1718 (85.5) | |||

| 6-8 (n = 2171) | 374 (17.2) | 565 (26.0) | 1893 (87.2) | |||

| >9 (n = 9054) | 2087 (23.1) | 3292 (36.4) | 8433 (93.1) | |||

3.3. Predictors of ED visit types among Medicaid beneficiaries with comorbid diabetes and schizophrenia

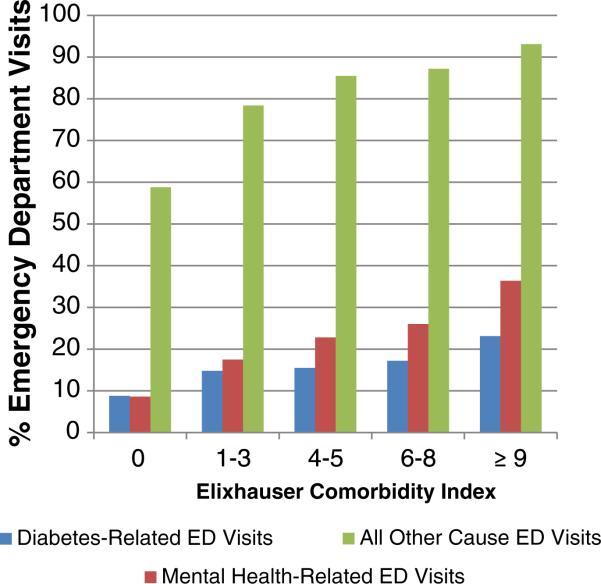

As shown in Table 3, among individuals with comorbid diabetes and schizophrenia, significant predictors (p < .01) of diabetes related ED visits in the logistic regression model were black race and having 1 or more comorbidities. Higher comorbidity scores were a strong predictor of diabetes-related ED visits. Significant predictors of any mental health-related ED visits were ages 18–29 years old, residence in a small or large metropolitan area (population greater than 250 000), and treatment with atypical antipsychotics or a combination of typical and atypical antipsychotics. Black and Hispanic races/ethnicities were predictive of lower rates of mental health-related ED visits compared to whites. Greater numbers of comorbidities were more strongly predictive of mental health-related visits than diabetes-related visits. Male gender and older age were predictive of lower rates of all other causes of ED visits. No treatment with any antipsychotic medication was predictive of higher all other cause ED visits, as were treatment with atypical antipsychotics or combination atypical and typical antipsychotics. Non-Hispanic white and Hispanic races/ethnicities were predictive of lower rates of all other causes of ED visits compared to blacks. As with diabetes-related and mental health-related ED visits, greater comorbidity was strongly predictive of higher rates of all other causes of ED visits, as demonstrated in Figure 1.

Table 3.

Crude and adjusted odds ratios (OR) of ED visits based on logistic regression model among patients with schizophrenia and diabetes.

| Diabetes-related ED visits |

Mental health-related ED visits |

All other cause ED visits |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crude OR (95% CI) | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | Crude OR (95% CI) | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | Crude OR (95% CI) | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | |

| Age group (reference group = 45–64 years old) | ||||||

| 45–64 years | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 18–29 years | 1.13 (0.99,1.30) | 1.19 (1.04,1.37)a | 2.13 (1.91,2.38)a | 2.42 (2.15,2.73)a | 1.38 (1.20,1.59)a | 1.71 (1.47,1.98)a |

| 30–44 years | 1.16 (1.07,1.25)a | 1.22 (1.12,1.32)a | 1.58 (1.47,1.69)a | 1.73 (1.61,1.86)a | 1.18 (1.10,1.27)a | 1.37 (1.27,1.49)a |

| Race/ethnicity(reference group = White) | ||||||

| White | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Black | 1.25 (1.16,1.35)a | 1.37 (1.27,1.49)a | 0.78 ( 0.73, 0.83)a | 0.87 (0.81,0.93)a | 0.90 (0.84,0.97)a | 1.08 (1.00,1.17) |

| Hispanic | 0.70 (0.61,0.80)a | 0.70 (0.61,0.81 )a | 0.54 (0.48, 0.61)a | 0.55 (0.49, 0.62)a | 0.64 (0.57,0.71)a | 0.58 (0.52, 0.65)a |

| Asian | 0.86 (0.52,1.42) | 1.03 (0.62,1.71) | 0.66 (0.43,1.02) | 0.80 (0.50,1.26)a | 0.43 (0.30,0.62)a | 0.53 (0.36, 0.80)a |

| Other | 1.05 (0.92,1.20) | 1.13 (0.99, 1.30) | 0.61 (0.53, 0.69)a | 0.67 (0.59, 0.77)a | 0.77 (0.69,0.87)a | 0.84 (0.73, 0.95)a |

| Gender(reference group = Male) | ||||||

| Male | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Female | 1.06 (0.99,1.14) | 1.00 (0.93,1.07) | 1.08(1.01,1.15)a | 1.04 (0.97,1.12) | 1.64 (1.53,1.75)a | 1.58 (1.47,1.70)a |

| Rural/urban status(reference group = Rural Area) | ||||||

| <250 000 rural area | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| > 1 million metro area | 1.13 (1.04,1.23)a | 1.03 (0.94,1.12) | 1.32 (1.22,1.42)a | 1.24 (1.15,1.34)a | 1.14 (1.06,1.24)a | 1.08 (0.99,1.18) |

| 250 000–1 million small metro area | 1.07 (0.99,1.16) | 1.06 (0.98,1.15) | 1.09 (1.02,1.18)a | 1.15 (1.07,1.24)a | 1.05 (0.97,1.23) | 1.12(1.03,1.21) |

| Treatment (reference group = typical antipsychotics) | ||||||

| Typical antipsychotics | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Atypical antipsychotics | 0.97 (0.85,1.01) | 0.89 (0.77,1.02) | 1.59 (1.39,1.83)a | 1.25 (1.08,1.45)a | 1.42 (1.27,1.58)a | 1.14 (1.01,1.28)a |

| Both | 1.20 (1.04,1.38)a | 0.99 (0.85,1.14)a | 3.50 (3.04,4.04)a | 2.54 (2.19, 2.95)a | 2.31 (2.04,2.61)a | 1.59 (1.39,1.81 )a |

| None | 1.23 (1.04,1.46)a | 1.12 (0.94, 1.32) | 1.29 (1.08,1.54)a | 1.00 (0.83,1.20) | 1.83 (1.57,2.13)a | 1.53 (1.29,1.80)a |

| Elixhauser comorbidity index (reference group = 0) | ||||||

| 0 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||

| 1–3 | 1.78 (1.58,2.01)a | 1.83 (1.62,2.07)a | 2.24 (1.99, 2.52)a | 2.17 (1.93,2.45)a | 2.55 (2.33,2.78)a | 2.54 (2.32, 2.78)a |

| 4–5 | 1.89 (1.63,2.19)a | 1.97 (1.69,2.29)a | 3.13 (2.73, 3.59)a | 3.10 (2.70, 3.57)a | 4.13 (3.61,4.72)a | 4.23 (3.69,4.85)a |

| 6–8 | 2.14(1.86,2.47)a | 2.29 (1.98,2.64)a | 3.73 (3.28,4.25)a | 3.74 (3.27,4.27)a | 4.78 (4.18,5.47)a | 4.95 (4.31,5.68)a |

| ≥9 | 3.09 (2.79,3.41)a | 3.31 (2.99,3.66)a | 6.06 (5.50, 6.68)a | 6.09 (5.51,6.73)a | 9.53 (8.66,10.49)a | 9.78 (8.86,10.78)a |

p < 0.05.

Fig. 1.

Percentage of diabetes-related, mental health-related, and all other cause emergency department visits by comorbidities in a population of individuals with schizophrenia and diabetes.

3.4. Causes of ED visits among Medicaid beneficiaries with comorbid schizophrenia and diabetes

The most common causes of ED visits among individuals with comorbid schizophrenia and diabetes were “symptoms, signs, and ill-defined conditions” such as shortness of breath, fatigue/malaise, and “general symptoms,” injury and poisoning, and musculoskeletal symptoms. The leading causes of ED visits for the diabetes and schizophrenia sample are listed in Table 4.

Table 4.

Summary of all other cause emergency department visits by diagnostic category in individuals with both diabetes and schizophrenia.

| ICD-9 (3-digit) | Number of ED visits by diagnosis | Percent | Description | Most common diagnoses in this category |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 780–799a | 111 303 | 33.8% | Symptoms, signs, & ill-defined conditions | Chest symptoms, shortness of breath, “general symptoms”: fatigue/malaise etc.; nausea, dizziness, etc. |

| 800–999 | 38 894 | 11.8% | Injury and poisoningb | Sprains, strains, contusions, lacerations; face, skull, and extremity fractures; medication overdose (psychogenic and medical Rx) |

| 710–739 | 27 226 | 8.3% | Musculoskeletal diseases or symptoms | Neck pain, back pain, non-specificpain, and osteoarthritis |

| 460–519 | 20 383 | 6.2% | Respiratory system diseases or symptoms | Asthma, pneumonia, and other obstructive lung disease |

| 290–319 | 19 000 | 5.8% | Other mental health diagnoses | Bipolar illness, depressive symptoms, conduct disturbance, mental retardation, and other psychiatric symptoms (body rocking, etc.) |

| 390–159 | 13 315 | 4.0% | Circulatory/cardiovascular | Hypertension, heart failure, arrhythmias, and coronary disease |

| 520–579 | 12 852 | 3.9% | Gastrointestinal/digestive | Gastroenteritis, constipation, GERD, and dental problems; GI bleeding |

| 580–629 | 9421 | 2.9% | Genitourinary | UTI, urethritis, menstrual pain and bleeding abnormalities |

| 001–139 | 8059 | 2.4% | Infections | Viral/chlamydial infections, HIV, sepsis |

| 320–389 | 7651 | 2.3% | Nervous system | Migraine, epilepsy, other headache, and otitis |

| 680–709 | 7374 | 2.2% | Skin and subcutaneous tissue | Cellulitis, abscess, dermatitis, rash, skin ulcer |

ICD-9 codes in the range of 780 to 780.xx include diagnoses which could be tied to schizophrenia explicitly (e.g., 780.01 = hallucinations), or implicitly (e.g., altered consciousness [780.09] or transient alteration of awareness [780.02]).

Additional injury visits identified by E-codes are not included in this count

4. Discussion

4.1. The impact of comorbidity

Our findings help to quantify ED utilization in a combination of multiple chronic conditions, diabetes and schizophrenia. Comorbid diabetes and schizophrenia results in higher levels of ED visits compared to individuals with diabetes only, schizophrenia only, or other chronic physical illnesses. Greater numbers of comorbid conditions predicted higher rates of diabetes, mental health, and all other-cause visits in individuals with comorbid diabetes and schizophrenia. These all other-cause ED visit rates are more than ten times higher for those with the highest comorbidity scores versus the lowest, even within the already high-risk sub-population of Medicaid enrollees with both schizophrenia and diabetes.

Although in 1943 the combination of schizophrenia and diabetes was described as “extremely rare,” this comorbidity cluster is known to be more common in present day (Kasin and Parker, 1943; Dixon et al., 2000; Rouillon and Sorbara, 2005). When evaluating diabetes and schizophrenia more closely, the highest rates of ED visits are for all other causes than diabetes or mental health chief complaints. Individuals with schizophrenia have greater severity of physical illness, and often have lower quality of care associated with treatment of physical conditions (Goldberg et al., 2007; Leucht et al., 2007; Bresee et al., 2012). Individuals with diabetes are at greater risk for various physical complications associated with their illness, including heart disease, blindness, renal failure, and extremity amputations (Dall et al., 2003). The complexity of comorbid diabetes and schizophrenia may lead to increased ED usage in all areas of health, not just for diabetes related or schizophrenia related complications of the illnesses.

Previous research has confirmed that quality of diabetes care for individuals with schizophrenia is not worse than care for the general population (Desai et al., 2002; Dixon et al., 2004; Krein et al., 2006). Even so, some primary care providers report difficulty communicating effectively and providing effective care for individuals with serious mental illness (Lester et al., 2005). Furthermore, individuals with serious mental illness frequently have less general preventive medical care compared to the general population (Druss et al., 2002). Thus, the causes of disability and illness in this specific population may be more complex than concentrating care management efforts specifically on schizophrenia or diabetes. Patients with comorbid schizophrenia and diabetes may benefit from greater emphasis on overall health promotion and prevention activities, focused on decreasing risk associated with various general medical conditions.

4.2. Racial/ethnic disparities

Racial and ethnic disparities exist among patients with comorbid schizophrenia and diabetes. Although racial/ethnic disparities associated with schizophrenia are focused more on access to care and poorer quality of care than racial differences in incidence or prevalence, the racial/ethnic disparities in diabetes also highlight incidence and prevalence differences, with blacks and Hispanics having higher rates of diabetes compared to whites (Brancati et al., 2000; McBean et al., 2004). Our analysis found higher rates of diabetes-related ED visits among blacks than whites and Hispanics, and after controlling for covariates, these racial disparities persisted. For mental health-related visits, whites had the highest ED visit rates compared to all other racial/ethnic groups, a trend which was strikingly different when compared to diabetes-related and all other-cause ED visits. This finding is inconsistent with research that has shown higher rates of ED utilization for mental health problems among blacks (with less outpatient mental health treatment) compared to non-Hispanic whites (Hu et al., 1991; Snowden and Holschuh, 1992; Chow et al., 2003). However, in recent years, rates of non-Hispanic white populations accessing ED settings for mental health related issues have been increasing while rates in minority populations have remained stable—these findings may confirm a shift in the trend (Larkin et al., 2005).

Social complexity and its direct association with access to care are difficult to clearly delineate. Access to care may be reduced for racial/ethnic minority populations due to a number of factors, including geographical barriers, attitudes toward treatment-seeking, and poor therapeutic alliance (Sussman et al., 1987; Cooper-Patrick et al., 1997; US Department of Health and Human Services, 2001; Shim et al., 2009). Blacks have higher rates of diabetes than whites, and whites are more likely to have greater access to mental health services and receive atypical antipsychotics than blacks, which may lead to worsening physical health outcomes among blacks, and may have an impact on all other cause and diabetes-related ED utilization (Kreyenbuhl et al., 2003).

4.3. Treatment considerations

The burden of disease associated with multiple chronic conditions, and the limitations of current single-disease focused clinical practice guidelines make it difficult to offer specific evidence-based recommendations with regard to achieving optimal outcomes in this population (Boyd et al., 2005; Fortin et al., 2006). Clearly, multi-morbidity leads to unnecessary hospitalizations, adverse drug events, health care expenditures, disability, and mortality. This is exacerbated by fragmentation in the health care system, in which multiple clinicians manage individual diseases in a single patient without effectively communicating or sharing in decision-making, often with delays in care or duplicated services. The impact of fragmentation is addressed in the Institute of Medicine report Crossing the Quality Chasm (Institute of Medicine Committee on Quality of Health Care in America, 2001; Vogeli et al., 2007; Parekh and Barton, 2010).

The sheer medical and social complexity of diabetes and schizophrenia require targeted interventions to specifically address the complications associated with multiple chronic conditions (Piette and Kerr, 2006). Recommendations and guidelines aimed at improved monitoring of physical health for individuals for schizophrenia have helped to move usual care toward the direction of improved health outcomes (Marder et al., 2004). Medical care management programs have been shown to improve overall health outcomes among individuals with schizophrenia and other serious mental illness (Ohlsen et al., 2005; Druss et al., 2010a). In fact, interventions targeting patients with comorbid diabetes and schizophrenia have been shown to result in greater weight loss, lower triglycerides, and increased diabetes self-efficacy (McKibbin et al., 2006). Increasing focus on primary care has been shown to reduce ED visits in patients with chronic illness; however, few interventions have been effective in reducing ED utilization in patients with serious mental illness (Latimer, 1999; Coleman et al., 2001). Chronic disease self-management programs have shown efficacy in the management of diabetes, and preliminary testing chronic disease self-management programs in individuals with serious mental illness are promising (Newman et al., 2004; Druss et al., 2010b). Also, integrated and co-located primary care and mental health services have demonstrated improved physical health outcomes for individuals with serious mental illnesses (Pirraglia et al., 2012). Additional testing of innovative models is needed to ensure that patients with comorbid diabetes and schizophrenia receive team-based care that emphasizes whole-person health, rather than management of specific disease states.

4.4. Limitations

There are several limitations that should be discussed. The limitations of Medicaid claims data have been previously documented (Bright et al., 1989), especially with regard to the accuracy of diagnosis coding in various claims and the completeness of our capturing of ED visits through claims data (Lurie et al., 1992). However, we have used specific methodology strategies to minimize the impact of this limitation and to improve reliability (Walkup et al., 2000). Similarly, accuracy of coding race–ethnicity is subject to the accurate recording of self-described racial/ethnic group during the Medicaid enrollment process. In evaluating racial/ethnic disparities, we know that socioeconomic status also plays a significant role, but we did not analyze socioeconomic status within this Medicaid population. However, all Medicaid enrollees are at least somewhat similar socioeconomically in having to prove low-income status as an essential basis for Medicaid eligibility. Additionally, the Medicaid sample consisted of 14 Southern states, which does somewhat limit generalizability of these findings. However, this particular sample comprises the majority of African American patients with Medicaid coverage in the United States, which increases opportunities to examining disparities between African American and non-Hispanic white patients with schizophrenia and diabetes.

4.5. Clinical implications

This study focuses on a specific comorbidity cluster that combines a “physical” disease requiring effective self-management and a “mental health” disease that can profoundly affect an individual's ability to manage self-care and overall health. Single disease models of disease management are unlikely to be effective in addressing the complexities of these patients to improve overall health outcomes. The impact of additional comorbidities beyond the diabetes–schizophrenia dyad raises the clinical complexity of these patients even further, and the combination of poverty and racial/ethnic disparities adds an additional layer of social complexity. Greater understanding of the rate and type of ED visits among individuals with comorbid diabetes and schizophrenia can help add context and insight to related measures within the Medicaid population, including inpatient and outpatient service utilization, expenditures, and mortality. Clinicians and healthcare professionals serving patients with comorbid diabetes and schizophrenia should consider integrated approaches to the management of the whole person in social context, in order to decrease overall ED utilization, to improve quality of care, and to achieve optimal outcomes in such challenging combinations of psychiatric and medical chronic diseases.

Acknowledgments

The authors have no acknowledgements to report.

Role of the funding source

This project was funded under contract/grant number R24 HS 019470-01 from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The opinions expressed in this document are those of the authors and do not reflect the official position of AHRQ or the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Footnotes

Contributors

Ruth Shim designed the study and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. Benjamin Druss wrote and reviewed all manuscript drafts and designed the study. Shun Zhang undertook the statistical analysis and wrote the portions of the manuscript. Giyeon Kim wrote and reviewed all manuscript drafts. Adesoji Oderinde and Sosunmolu Shoyinka reviewed all manuscript drafts. George Rust designed the study, managed the analyses, and wrote and reviewed all manuscript drafts. All authors contributed to and have approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of interest

George Rust, MD, MPH is the principal investigator of a center grant from the Bristol-Myers Squibb Foundation. All other authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- Al-Zakwani IS, Barron JJ, Bullano MF, Arcona S, Drury CJ, Cockerham TR. Analysis of healthcare utilization patterns and adherence in patients receiving typical and atypical antipsychotic medications. Curr. Med. Res. Opin. 2003;19(7):619–626. doi: 10.1185/030079903125002270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP) Psychiatric and Substance Abuse Survey, 2008. [March 26, 2013];Fact Sheet. (Available at: http://www.acep.org/uploadedFiles/ACEP/Advocacy/federal_issues/PsychiatricBoardingSummary.pdf)

- Becker T, Hux J. Risk of acute complications of diabetes among people with schizophrenia in Ontario, Canada. Diabetes Care. 2011;34(2):398–402. doi: 10.2337/dc10-1139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd CM, Darer J, Boult C, Fried LP, Boult L, Wu AW. Clinical practice guidelines and quality of care for older patients with multiple comorbid diseases. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2005;294(6):716–724. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.6.716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brancati FL, Kao WHL, Folsom AR, Watson RL, Szklo M. Incident type 2 diabetes mellitus in African American and white adults. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2000;283(17):2253–2259. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.17.2253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bresee LC, Majumdar SR, Patten SB, Johnson JA. Utilization of general and specialized cardiac care by people with schizophrenia. Psychiatr. Serv. 2012;63(3):237–242. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201000363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bright RA, Avorn J, Everitt DE. Medicaid data as a resource for epidemiologic studies: strengths and limitations. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 1989;42(10):937–945. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(89)90158-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bushe C, Holt R. Prevalence of diabetes and impaired glucose tolerance in patients with schizophrenia. Br. J. Psychiatry. 2004;184(47):s67–s71. doi: 10.1192/bjp.184.47.s67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chow JC-C, Jaffee K, Snowden L. Racial/ethnic disparities in the use of mental health services in poverty areas. Am. J. Public Health. 2003;93(5):792–797. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.5.792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman E, Eilertsen T, Kramer A, Magid D, Beck A, Conner D. Reducing emergency visits in older adults with chronic illness. A randomized, controlled trial of group visits. Eff. Clin. Pract. 2001;4(2):49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colton C, Manderscheid R. Congruencies in increased mortality rates, years of potential life lost, and causes of death among public mental health clients in eight states. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2006;3(2):A42. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper-Patrick L, Powe NR, Jenckes MW, Gonzales JJ, Levine DM, Ford DE. Identification of patient attitudes and preferences regarding treatment of depression. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 1997;12(7):431–438. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1997.00075.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curran GM, Sullivan G, Williams K, Han X, Collins K, Keys J, Kotrla KJ. Emergency department use of persons with comorbid psychiatric and substance abuse disorders. Ann. Emerg. Med. 2003;41(5):659–667. doi: 10.1067/mem.2003.154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dall T, Nikolov P, Hogan P. Economic costs of diabetes in the US in 2002. Diabetes Care. 2003;26:917–932. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.3.917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desai MM, Rosenheck RA, Druss BG, Perlin JB. Mental disorders and quality of diabetes care in the veterans health administration. Am. J. Psychiatr. 2002;159(9):1584–1590. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.9.1584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhossche DM, Ghani SO. A study on recidivism in the psychiatric emergency room. Ann. Clin. Psychiatry. 1998;10(2):59–67. doi: 10.1023/a:1026162931925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickerson F, Goldberg R, Brown C, Kreyenbuhl J, Wohlheiter K, Fang L, Medoff D, Dixon L. Diabetes knowledge among persons with serious mental illness and type 2 diabetes. Psychosomatics. 2005;46(5):418. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.46.5.418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickerson FB, McNary SW, Brown CH, Kreyenbuhl J, Goldberg RW, Dixon LB. Somatic healthcare utilization among adults with serious mental illness who are receiving community psychiatric services. Med. Care. 2003;41(4):560–570. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000053440.18761.F0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon L, Weiden P, Delahanty J, Goldberg R, Postrado L, Lucksted A, Lehman A. Prevalence and correlates of diabetes in national schizophrenia samples. Schizophr. Bull. 2000;26(4):903–912. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a033504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon LB, Kreyenbuhl JA, Dickerson FB, Donner TW, Brown CH, Wolheiter K, Postrado L, Goldberg RW, Fang LJ, Marano C. A comparison of type 2 diabetes outcomes among persons with and without severe mental illnesses. Psychiatr. Serv. 2004;55(8):892–900. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.55.8.892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Druss BG, Rosenheck RA, Desai MM, Perlin JB. Quality of preventive medical care for patients with mental disorders. Med. Care. 2002;40(2):129–136. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200202000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Druss BG, Silke A, Compton MT, Rask KJ, Zhao L, Parker RM. A randomized trial of medical care management for community mental health settings: the Primary Care Access, Referral, and Evaluation (PCARE) study. Am. J. Psychiatr. 2010a;167(2):151–159. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09050691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Druss BG, Zhao L, Von Esenwein S, Morrato EH, Marcus SC. Understanding excess mortality in persons with mental illness: 17-year follow up of a nationally representative US survey. Med. Care. 2011;49(6):599–604. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31820bf86e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Druss BG, Zhao L, von Esenwein SA, Bona JR, Fricks L, Jenkins-Tucker S, Sterling E, DiClemente R, Lorig K. The Health and Recovery Peer (HARP) Program: a peer-led intervention to improve medical self-management for persons with serious mental illness. Schizophr. Res. 2010b;118(1):264–270. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2010.01.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egede LE. Patterns and correlates of emergency department use by individuals with diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2004;27(7):1748–1750. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.7.1748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elixhauser A, Steiner C, Harris DR, Coffey RM. Comorbidity measures for use with administrative data. Med. Care. 1998;36(1):8–27. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199801000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fogarty CT, Sharma S, Chetty VK, Culpepper L. Mental health conditions are associated with increased health care utilization among urban family medicine patients. J. Am. Board Fam. Med. 2008;21(5):398–407. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2008.05.070082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fortin M, Dionne J, Pinho G, Gignac J, Almirall J, Lapointe L. Randomized controlled trials: do they have external validity for patients with multiple comorbidities? Ann. Fam. Med. 2006;4(2):104–108. doi: 10.1370/afm.516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg R, Kreyenbuhl J, Medoff D, Dickerson F, Wohlheiter K, Fang LJ, Brown C, Dixon L. Quality of diabetes care among adults with serious mental illness. Psychiatr. Serv. 2007;58(4):536–543. doi: 10.1176/ps.2007.58.4.536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hackman A, Goldberg R, Brown C, Fang L, Dickerson F, Wohlheiter K, Medoff D, Kreyenbuhl J, Dixon L. Brief reports: use of emergency department services for somatic reasons by people with serious mental illness. Psychiatr. Serv. 2006;57(4):563–566. doi: 10.1176/ps.2006.57.4.563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hazlett SB, McCarthy ML, Londner MS, Onyike CU. Epidemiology of adult psychiatric visits to US emergency departments. Acad. Emerg. Med. 2004;11(2):193–195. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendrie HC, Lindgren D, Hay DP, Lane KA, Gao S, Purnell C, Munger S, Smith F, Dickens J, Boustani MA. Comorbidity profile and healthcare utilization in elderly patients with serious mental illnesses. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry. 2013;21(12):1267–1276. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2013.01.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Himelhoch S, Weller WE, Wu AW, Anderson GF, Cooper LA. Chronic medical illness, depression, and use of acute medical services among Medicare beneficiaries. Med. Care. 2004;42(6):512–521. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000127998.89246.ef. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu T.-w, Snowden LR, Jerrell JM, Nguyen TD. Ethnic populations in public mental health: services choice and level of use. Am. J. Public Health. 1991;81(11):1429–1434. doi: 10.2105/ajph.81.11.1429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine Committee on Quality of Health Care in America . Crossing the quality chasm: a new health system for the 21st century. National Academies Press; 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasin E, Parker S. Schizophrenia and diabetes. Am. J. Psychiatr. 1943;99(6):793–797. [Google Scholar]

- Krein S, Bingham CR, McCarthy J, Mitchinson A, Payes J, Valenstein M. Diabetes treatment among VA patients with comorbid serious mental illness. Psychiatr. Serv. 2006;57(7):1016–1021. doi: 10.1176/ps.2006.57.7.1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreyenbuhl J, Zito JM, Buchanan RW, Soeken KL, Lehman AF. Racial disparity in the pharmacological management of schizophrenia. Schizophr. Bull. 2003;29(2):183–194. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a006996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larkin GL, Claassen CA, Emond JA, Pelletier AJ, Camargo CA. Trends in US emergency department visits for mental health conditions, 1992 to 2001. Psychiatr. Serv. 2005;56(6):671–677. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.56.6.671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latimer EA. Economic impacts of assertive community treatment: a review of the literature. Can. J. Psychiatr. 1999;44(5):443–454. doi: 10.1177/070674379904400504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lester H, Tritter JQ, Sorohan H. Patients' and health professionals' views on primary care for people with serious mental illness: focus group study. Br. Med. J. 2005;330(7500):1122. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38440.418426.8F. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leucht S, Burkard T, Henderson J, Maj M, Sartorius N. Physical illness and schizophrenia: a review of the literature. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2007;116(5):317–333. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2007.01095.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin M-T, Burgess JF, Jr., Carey K. The association between serious psychological distress and emergency department utilization among young adults in the USA. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2012;47(6):939–947. doi: 10.1007/s00127-011-0401-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lurie N, Popkin M, Dysken M, Moscovice I, Finch M. Accuracy of diagnoses of schizophrenia in Medicaid claims. Hosp. Community Psychiatry. 1992;43(1):69–71. doi: 10.1176/ps.43.1.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mai Q, Holman CDA, Sanfilippo F, Emery J, Preen D. Mental illness related disparities in diabetes prevalence, quality of care and outcomes: a population-based longitudinal study. BMC Med. 2011;9(1):118. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-9-118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marder SR, Essock SM, Miller AL, Buchanan RW, Casey DE, Davis JM, Kane JM, Lieberman JA, Schooler NR, Covell N. Physical health monitoring of patients with schizophrenia. Am. J. Psychiatr. 2004;161(8):1334–1349. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.8.1334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McBean AM, Li S, Gilbertson DT, Collins AJ. Differences in diabetes prevalence, incidence, and mortality among the elderly of four racial/ethnic groups: whites, blacks, Hispanics, and Asians. Diabetes Care. 2004;27(10):2317–2324. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.10.2317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCusker J, Cardin S, Bellavance F, Belzile E. Return to the emergency department among elders: patterns and predictors. Acad. Emerg. Med.: Off. J. Soc. Acad. Emerg. Med. 2000;7(3):249–259. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2000.tb01070.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKibbin CL, Patterson TL, Norman G, Patrick K, Jin H, Roesch S, Mudaliar S, Barrio C, O'Hanlon K, Griver K. A lifestyle intervention for older schizophrenia patients with diabetes mellitus: a randomized controlled trial. Schizophr. Res. 2006;86(1):36–44. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2006.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moineddin R, Meaney C, Agha M, Zagorski B, Glazier RH. Modeling factors influencing the demand for emergency department services in Ontario: a comparison of methods. BMC Emerg. Med. 2011;11(1):13. doi: 10.1186/1471-227X-11-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee S, Decina P, Bocola V, Saraceni F, Scapicchio P. Diabetes mellitus in schizophrenic patients. Compr. Psychiatry. 1996;37(1):68–73. doi: 10.1016/s0010-440x(96)90054-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman S, Steed L, Mulligan K. Self-management interventions for chronic illness. Lancet. 2004;364(9444):1523–1537. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17277-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohlsen R, Peacock G, Smith S. Developing a service to monitor and improve physical health in people with serious mental illness. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2005;12(5):614–619. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2850.2005.00884.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandya A, Larkin GL, Randles R, Beautrais AL, Smith RP. Epidemiological trends in psychosis-related Emergency Department visits in the United States, 1992–2001. Schizophr. Res. 2009;110(1):28–32. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2008.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parekh AK, Barton MB. The challenge of multiple comorbidity for the US health care system. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2010;303(13):1303–1304. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parekh AK, Goodman RA, Gordon C, Koh HK. Managing multiple chronic conditions: a strategic framework for improving health outcomes and quality of life. Public Health Rep. 2011;126(4):460. doi: 10.1177/003335491112600403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parks J, Svendsen D, Singer P, Foti ME, Mauer B. Morbidity and Mortality in People with Serious Mental Illness. National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors (NASMHPD) Medical Directors Council; Alexandria, VA: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Piette J, Heisler M, Ganoczy D, McCarthy J, Valenstein M. Differential medication adherence among patients with schizophrenia and comorbid diabetes and hypertension. Psychiatr. Serv. 2007;58(2):207. doi: 10.1176/ps.2007.58.2.207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piette JD, Kerr EA. The impact of comorbid chronic conditions on diabetes care. Diabetes Care. 2006;29(3):725–731. doi: 10.2337/diacare.29.03.06.dc05-2078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pirraglia PA, Rowland E, Wu W-C, Friedmann PD, O'Toole TP, Cohen LB, Taveira TH. Benefits of a primary care clinic co-located and integrated in a mental health setting for veterans with serious mental illness. Prev. Chronic. Dis. 2012;9 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rouillon F, Sorbara F. Schizophrenia and diabetes: epidemiological data. Eur. Psychiatry. 2005;20:S345–S348. doi: 10.1016/s0924-9338(05)80189-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salsberry PJ, Chipps E, Kennedy C. Use of general medical services among Medicaid patients with severe and persistent mental illness. Psychiatr. Serv. 2005;56(4):458–462. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.56.4.458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shim R, Compton M, Rust G, Druss B, Kaslow N. Race–ethnicity as a predictor of attitudes toward mental health treatment seeking. Psychiatr. Serv. 2009;60(10):1336–1341. doi: 10.1176/ps.2009.60.10.1336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snowden LR, Holschuh J. Ethnic differences in emergency psychiatric care and hospitalization in a program for the severely mentally ill. Community Ment. Health J. 1992;28(4):281–291. doi: 10.1007/BF00755795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Southern DA, Quan H, Ghali WA. Comparison of the Elixhauser and Charlson/Deyo methods of comorbidity measurement in administrative data. Med. Care. 2004;42(4):355–360. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000118861.56848.ee. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subramaniam M, Chong S-A, Pek E. Diabetes mellitus and impaired glucose tolerance in patients with schizophrenia. Can. J. Psychiatr. 2003;48(5):345–347. doi: 10.1177/070674370304800512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sussman LK, Robins LN, Earls F. Treatment-seeking for depression by black and white Americans. Soc. Sci. Med. 1987;24(3):187–196. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(87)90046-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- US Department of Health and Human Services . Mental Health: Culture, Race, and Ethnicity—A Supplement to Mental Health: A Report of the Surgeon General. US Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Mental Health Services; Rockville: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Vogeli C, Shields AE, Lee TA, Gibson TB, Marder WD, Weiss KB, Blumenthal D. Multiple chronic conditions: prevalence, health consequences, and implications for quality, care management, and costs. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2007;22:391–395. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0322-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walkup JT, Boyer CA, Kellermann SL. Reliability of Medicaid claims files for use in psychiatric diagnoses and service delivery. Adm. Policy Ment. Health Ment. Health Serv. Res. 2000;27(3):129–139. doi: 10.1023/a:1021308007343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]