Abstract

Teaching parents to be mindful in their daily interactions with their adolescents may be one way to improve the quality of parent-youth relationships and positively affect youth psychological development. Mindfulness in parenting may be especially helpful during adolescence, when youth experience many rapid cognitive, emotional and social changes. The Mindfulness-enhanced Strengthening Families Program (MSFP) teaches both mindfulness and parenting skills to parents of adolescents. In this article we review the theoretical and empirical foundations of the program, describe sample activities, and highlight the advantages of a mindfulness-based, family-focused approach with adolescents.

Adolescence: Risk, Family Relationships and Interventions

The ways in which parents support their adolescents emotionally, cognitively and physically and teach them to manage emotionally arousing situations are fundamental to adolescent mental health and well-being.1 When parents lack youth management and relationship skills, they increase their adolescents’ risk for problem behaviors.2 Fortunately, prevention programs are effective in helping parents develop parenting skills to support healthy youth development.3

Parent-Youth Relationships

A central goal of such prevention programs is strengthening parent-youth relationships that socialize healthy adolescent skills, values and behaviors. During adolescence, however, changes in the content and intensity of parent-youth interactions necessitate a reorganization of relationships.4 Misinterpretations and rapid emotional reactions can quickly transform innocuous interactions into highly charged exchanges. Problems emerge when parents respond with overreactive harsh discipline or avoidance and withdrawal. Rigidity during parent-youth conflict predicts adolescent problem behavior, whereas flexibility positively affects well-being.5

Mindfulness in Parenting and Mindful Parenting Interventions

The concept of mindfulness, commonly defined as nonjudgmental attention to one’s experiences in the present moment,6 is a promising concept for parenting research and interventions.7 Some conceptual models of mindfulness in parenting attend exclusively to parents’ experiences; their thoughts and feelings about being parents. We have proposed a conceptual model that attends both to parents’ intrapersonal mindfulness as well as to their interpersonal mindfulness, which focuses on how parents are “mindful” as they actually interact with their youths.7 The model, described more fully elsewhere,7 has five dimensions that were selected based on a review of the mindfulness and parenting literature: a) emotional awareness of self and child; b) self-regulation in the parenting relationship; c) non-judgmental acceptance of self and child; d) listening with full attention, and e) compassion for self and child. We hypothesize that mindfulness in parenting can be promoted and facilitates positive youth development because it increases the use of positive parenting strategies and decreases the use of negative parenting strategies and enhances positive parent-youth relationships.

Interventions to enhance mindful parenting show promise8 and have benefitted substantially from the literature supporting the efficacy of mindfulness-based interventions such as Mindfulness Based Stress Reduction (MBSR)9 and Mindfulness Based Cognitive Therapy (MBCT).10 Comprehensive programs like MBSR and MBCT promote mindfulness through extensive meditation training and daily home exercises while also fostering a broader ethical foundation of reducing suffering for oneself and others.6 Similarly, some mindful parenting interventions teach parents to meditate through in session and home practice exercises which theoretically alters cognitive and emotional processes that, in turn, lead to better parenting and parent-youth relationships even in the absence of direct parenting skills training.11 In contrast, we believe that the combination of brief mindfulness training coupled with parenting skills training, can help parents bring mindfulness into their everyday interactions with their youths and more effectively use their parenting skills in the moment. This intervention model is similar to other successful mindfulness-based approaches such as Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT)12 or Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT)13 which have blended skills training with brief mindfulness activities that focus on applying mindfulness in everyday life.

Developing a Mindful Parenting Intervention

To create MSFP we integrated mindfulness activities into an evidence-based family prevention program, the Strengthening Families Program: For Parents and Youth 10–14 (SFP 10–14).14 We selected SFP 10–14, because of its underlying philosophy of building new and enhancing existing individual and family strengths. We also selected it because of the strong evidence supporting its efficacy for improving parenting practices, enhancing youth development and preventing problem behavior.15 SFP 10–14 includes didactic and interactive training activities in highly structured two-hour sessions in which parents and youth meet separately for the first hour and conjointly for the second. We adopted SFP 10–14’s validated structure (e.g., number of sessions and format) and retained its core parent training activities. Working with the SFP developer, we created new activities based on core mindfulness practices that were common to other interventions but designed them to be appropriate for this parent training context and consistent with our conceptual model. We also added “mindfulness” language using words such as “presence,” “attention,” and “compassion.”

Mindful Parenting Activities in MSFP

Each session begins and ends with brief reflections. The reflections are 1–5 minute activities for parents to practice skills such as focused attention and deep breathing, while cultivating a kind attitude toward self and others. Most reflections also include setting intentions, such as parents reflecting on their purposes for attending MSFP or their wishes for their youths’ and their own well-being. Intention-setting is a conscious, motivational element of mindfulness practice that provides purpose to the direction of one’s attention and may be a central mechanism of mindfulness.16 Setting positive intentions may help shift parents’ attention or cognitive interpretations of their youths’ behaviors, facilitating more positive interactions. Transitions, like the start and end of sessions, are excellent opportunities for parents to stop and refocus their attention before consciously engaging with the next experience.

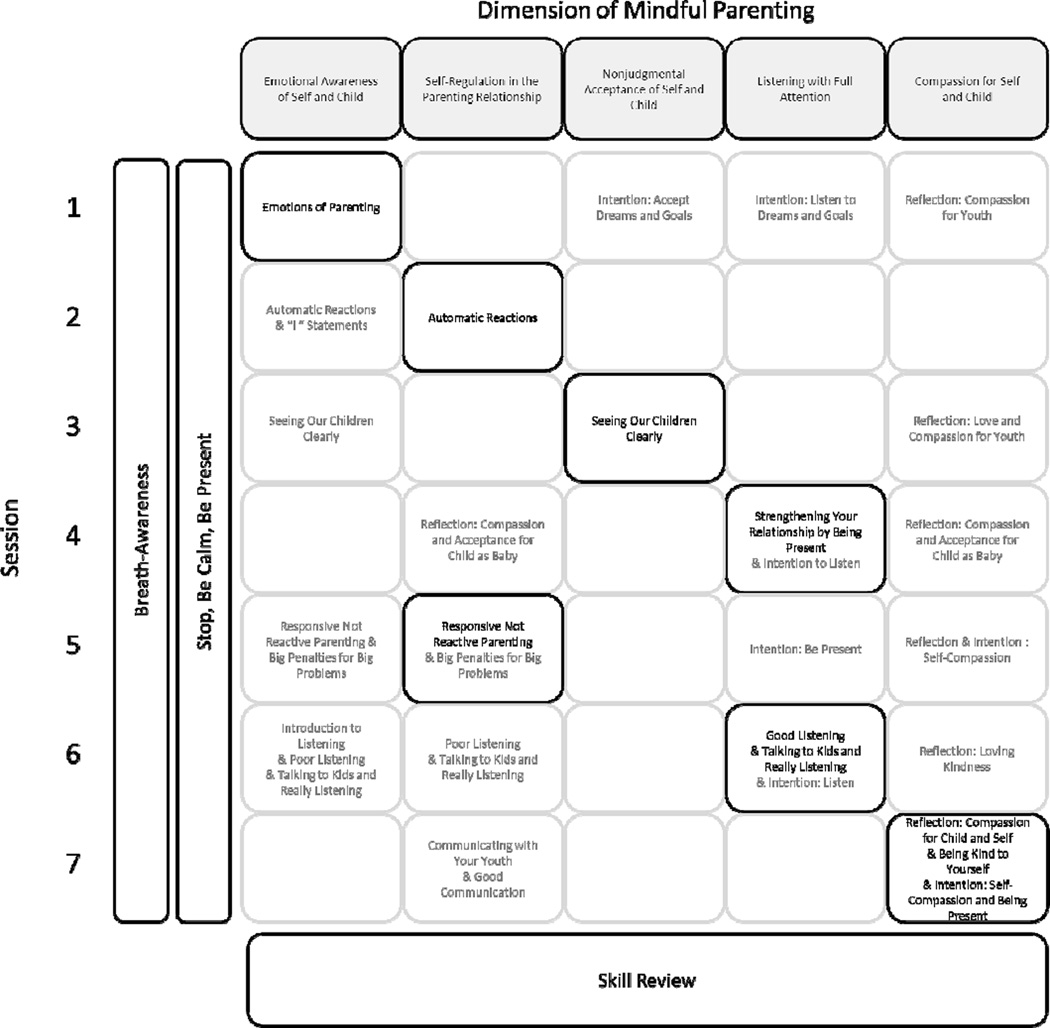

Below, we describe exemplary MSFP practices and activities to illustrate the intervention’s content and flow. Figure 1 displays the new mindfulness activities across the seven sessions and the five mindful parenting dimensions.

Figure 1.

Mindful parenting activities in MSFP by session and conceptual dimension

Breath awareness

Breath Awareness is a common practice in mindfulness training6 and is used throughout MSFP with the dual purpose of helping parents learn to focus their attention on the present moment and reduce stress. Breath awareness is an easily generalizable mindfulness practice that parents can use in any context, including during emotional interactions with their youths. Helping parents direct their attention to what is actually occurring in the present moment can assist with overriding automatized cognitive judgments, expectations and behavioral patterns developed during years of interactions. Moreover, deep breathing, also incorporated in the reflections, has been shown to increase parasympathetic tone which also helps parents focus their attention and remain calm during emotional situations.17 These calmer, more mindful interactions can facilitate more positive parent-youth relationships.

The first MSFP session opens with a breath awareness and deep breathing reflection. Facilitators model the technique and provide gentle instruction to parents. Parents discuss their experiences and often describe feeling awkward at first. Over the course of MSFP, parents gain comfort with using the breath as a foundational tool to practice being calm, present, and non-judgmentally responsive in a variety of situations, including parenting.

Breath awareness, used to regulate one’s attention, is a thread that ties together other mindfulness practices and is revisited during the opening and closing reflections of all seven sessions. As a reminder to use this practice when noticing emotional reactions while parenting, participants also receive a magnet printed with the phrase “Stop, Be Calm, Be Present.”

Emotions of parenting

Our conceptual and intervention models acknowledge that most parenting behaviors are activated because of emotional experiences.18 Years of emotional parent-youth exchanges can lead to ingrained patterns of interaction that shape the cognitive schemas and behaviors of both parents and youths. As a first step toward developing mindful parenting skills, we teach parents to recognize and acknowledge their emotions while parenting and to begin to explore how their emotional experiences influence reactions to youths’ behaviors. Teaching parents to recognize their emotions is similar to the mindfulness practice of noting and labeling emotions, which has been shown to facilitate emotion regulation.19

We ask parents to identify “comfortable” and “uncomfortable” feelings they have while parenting without judging those feelings as “good” or “bad.” Our intention is to help parents create a mindset that all emotions are temporary internal experiences that may not be avoidable and that recognition and acceptance of both comfortable and uncomfortable emotions will help them parent more mindfully and behave less reactively. Parents are encouraged to experience emotions as signals to refocus their attention to the present. We explain that the goal is to identify emotions before they become so strong that parents react in ways that exacerbate negative interactions.

Managing automatic reactions

Many human actions are guided by automatic cognitive and emotional process that are triggered by environmental events.20 Mindfulness brings awareness to automatic processes, enhancing the potential for conscious decision-making about behavioral responses. MSFP helps parents discern that automatic behavioral reactions usually are preceded by strong uncomfortable emotions that may overwhelm parents’ cognitive processes and leave them less able to parent intentionally. To gain some conscious control over automatic reactions, parents can become aware of and label feelings as they are arising, which provides the opportunity to pause and reflect before responding.

To help parents understand this process, MSFP asks them to generate a list of youth behaviors that trigger strong uncomfortable feelings, connect specific emotions to these triggers and identify automatic behavioral reactions, such as, yelling, blaming or punishing harshly. Parents also reflect on how youths might feel when parents react automatically. This final step helps develop perspective-taking skills which may enhance relationships through greater empathy, compassion and helping behavior.21 Parents discuss how their own trigger-emotion-behavioral reaction sequences can escalate and harm relationships. The take-home message is that by increasing self-awareness and noticing one’s feelings early, parents can see situations more clearly, respond in ways that are aligned with their parenting goals and prevent highly-charged and potentially relationship-damaging emotional interactions with their youths. A brief reflection, in which parents imagine a recent challenging exchange with their youth, guides parents to an understanding of how their growing skills of emotional awareness, cognitive recognition of triggers, and present-centered breath awareness can disrupt the escalation of the trigger-emotion-behavioral reaction sequence.

Seeing youths clearly

As MSFP progresses, activities become increasingly focused on mindful interpersonal relations and emphasize the approach of nonjudgmental awareness and acceptance of self and child. Acceptance of one’s experience in the present moment reduces active avoidance of uncomfortable thoughts or feelings, which may instead lead to reappraisal of uncomfortable experiences in more positive ways.22 Acceptance is also a form of perspective-taking related to empathy and compassionate actions for self and others.

Parents are asked to focus attention on their youths’ unique characteristics which helps them see their youths from a fresh perspective, without the cognitive biases and distortions of expectations and judgments formed over years. Reflection activities also direct parents to examine how their judgments or self-interest may lead them to misinterpret their youths’ intentions and behavior.

Non-judgmental acceptance has the goal of helping parents see their youths as they are and not how parents want them to be. Non-judgmental acceptance involves parents’ recognizing that youths have their own thoughts, feelings, desires, and goals, which may or may not align with what parents perceive or want. Non-judgmental acceptance is also about seeing beyond surface conditions to recognize and support a child’s true nature. Seeing one’s child clearly, without judgment, helps parents develop a fuller understanding of their youths’ internal lives and a more compassionate view of their youths’ experiences. Parents connect how their desires and expectations for their youth or their worries about their own parenting influences the quality of their relationships with their teens. Avoiding these evaluative thoughts can lead to parenting that is supportive and nurturing rather than critical and censoring.

Strengthening the parent-youth relationship by being present

Being present with their youths means that parents bring a gentle, non-judging and focused attention to what their youths are saying or doing in that moment. Parents are taught to notice when their minds wander and to consciously bring attention back to the present. By developing the capacity to focus their attention on the present moment, parents increase their ability to let go of worry about the past or the future, reduce their judgment of the situation, and become more fully attuned their own and their youths’ experiences, which can enhance their relationships.23

Parents consider what it means to be present and how it feels when someone is or is not giving them unidived attention. Parents identify situations when they are, or have been, fully present with their youths, and when they may not have been. Parents often acknowledge that because of their busy lives, their attention often wanders while their youths are talking, but they also recognize the value of listening with full attention. Parents practice this skill of regulating their attention by listening intently during the conjoint portion of the sessions and are also encouraged to practice at home.

Compassion for self and child

Parents enhance parent-youth relationships by treating their youths with empathy and compassion. Compassion for oneself, however, may be equally important in the practice of mindful parenting because it facilitates emotion regulation processes.22 When parents can replace harsh self-judgment with a compassionate approach to their parenting missteps, they are better able to be present for their youths and are better able to repair relationship disconnections. Throughout MSFP, activities are incorporated that promote caring and compassion for both the youth and oneself as a parent. Brief reflections, adapted from lovingkindness practices24 are designed to bring awareness of the challenges of being a youth and parenting a youth while promoting positive feelings toward one’s child and oneself. To encourage compassion for oneself, parents also reflect on effective aspects of their parenting.

When parents are struggling they often feel a sense of disconnection from their youths. Lovingkindness activities help parents reconnect with the positive feelings they have for their youths. Brief reflections ask parents to recall their youths as vulnerable infants or reflect on moments when their parent-youth relationships were especially close and loving. These reflections help parents connect to the accepting, loving, and compassionate feelings they have for their youths, remind parents that their youths still need love and support, and help parents see themselves and their parenting more positively.

Conclusions and Recommendations

Mindful parenting interventions are increasing in popularity as a strategy for reducing child and youth behavior problems, enhancing parent-child relationships, and fostering parents’ well-being. MSFP was designed to promote mindful parenting skills within the context of an existing empirically-validated family-based preventive intervention. We hypothesize that the mindfulness-based activities will allow parents to more effectively use the communication, monitoring, and behavior management skills they are also learning. We also hypothesize that the mindfulness-based activities will allow parents and youths to build and sustain more positive relationships during the adolescent transition when most parents and youths feel increasingly disconnected from one another.

A series of pilot studies showed that our strategy of infusing brief mindfulness activities into an evidence-based intervention is feasible, acceptable and can have salutary effects.25,26 We are now completing a large randomized clinical trial of the intervention with over 400 families from four communities in Pennsylvania. In this trial, we are comparing MSFP to both SFP 10–14 and a home-study control condition, in which parents receive information about adolescent development in the mail. Baseline, post-intervention, and one-year follow-up self-report and observational assessments are completed with mothers, fathers, and youths. More complete information about the design and the early findings from this intervention is available elsewhere.27

Results from this large trial will address several unanswered questions. First, results will answer whether, or in what ways, brief mindfulness activities can enhance the efficacy of an evidence-based family-skills intervention. Second, our design allows us to examine several different mediating mechanisms proposed in our conceptual model. Third, because we will have collected data from both mothers and fathers, we will have the rare opportunity to examine differential parenting effects. Finally, our multi-method assessment strategy will allow us to closely examine whether our intervention influenced interpersonal behavior and changed how parents and youths interact over time. We have proposed that changes in mindful parenting influence changes in relationship quality and youth behavior, but socialization occurs through dynamic interactions within parent-youth relationships.28 We will carefully attend to whether changes in adolescent behaviors might precipitate changes in parent mindfulness.

Finally, we are piloting an extension of our work in which we teach mindfulness strategies to both youths and parents separately and conjointly. Given findings that mindfulness training with youths can build life-skills, well-being and resilience,29 this strategy could further enhance the outcomes of universal, family-focused preventive interventions.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the National Institute on Drug Abuse for their support of this project through grant DA026217, and The Pennsylvania State University Children Youth and Families Consortium for their support of the pilot projects to develop the intervention. We would also like to sincerely thank Virginia Molgaard, an author of the original SFP for assisting us with our adaptation. We also thank Christa Turksma and Patricia Jennings for their input and assistance.

Footnotes

Headnote: Teaching parents mindfulness skills in the context of family-focused preventive interventions may be an effective way of enhancing youth wellness and reducing youth problem behavior.

Contributor Information

J. Douglas Coatsworth, Human Development and Family Studies at Colorado State University.

Larissa G. Duncan, Family and Community Medicine at the Osher Center for Integrative Medicine at the University of California – San Francisco School of Medicine.

Elaine Berrena, MSFP and has been a Prevention Educator at The Pennsylvania State University for more than 20 years.

Katharine T. Bamberger, Human Developmen and Family Studies at the Pennsylvania State University.

Daniel Loeschinger, psychology at the Friederich-Schiller University in Jena, Germany.

Mark T. Greenberg, The Department of Human Development & Family Studies at The Pennsylvania State University.

Robert L. Nix, Bennett Pierce Prevention Research Center at The Pennsylvania State University.

References

- 1.Morris AS, Silk JS, Steinberg L, Myers SS, Robinson LR. The role of the family context in the development of emotion regulation. Social Development. 2007;16:361–388. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9507.2007.00389.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dishion TJ, Kavanagh K. Intervening in adolescent problem behavior: A family-centered approach. Guilford Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kumpfer KL, Alvarado R. Family-strengthening approaches for the prevention of youth problem behaviors. American Psychologist. 2003;58:457–465. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.58.6-7.457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Granic I, Hollenstein T, Dishion TJ, Patterson GR. Longitudinal analysis of flexibility and reorganization in early adolescence: A dynamic systems study of family interactions. Developmental Psychology. 2003;39:606–617. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.39.3.606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hollenstein T, Granic I, Stoolmiller M, Snyder J. Rigidity in Parent-Child Interactions and the Development of Externalizing and Internalizing Behavior in Early Childhood. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2004;32:595–607. doi: 10.1023/b:jacp.0000047209.37650.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kabat-Zinn J. Full catastrophe living: Using the wisdom of your body and mind to face stress, pain, and illness. New York, NY US: Dell Publishing; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Duncan LG, Coatsworth JD, Greenberg MT. A model of mindful parenting: Implications for parent–child relationships and prevention research. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2009;12:255–270. doi: 10.1007/s10567-009-0046-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harnett PH, Dawe S. The contribution of mindfulness-based therapies for children and families and proposed conceptual integration. Child and Adolescent Mental Health. 2012;17:195–208. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-3588.2011.00643.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grossman P, Niemann L, Schmidt S, Walach H. Mindfulness-based stress reduction and health benefits: A meta-analysis. Journal of psychosomatic research. 2004;57:35–43. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3999(03)00573-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Segal ZV, Williams JMG, Teasdale JD. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for depression. New York, NY US: The Guilford Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bögels SM, Lehtonen A, Restifo K. Mindful parenting in mental health care. Mindfulness. 2010;1:107–120. doi: 10.1007/s12671-010-0014-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Linehan M. Cognitive behavioral treatment of borderline personality disorder. Guilford Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hayes SC, Strosahl KD, Wilson KG. Acceptance and commitment therapy: An experiential approach to behavior change. Guilford Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Molgaard V, Kumpfer KL, Fleming E. The Strengthening Families Program: For Parents and Youth 10–14; A video-based curriculum. Ames, IA: Iowa State University Extension; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Spoth RL, Shin C, Redmond C. Long-term effects of universal preventive interventions on methamphetamine use among adolescents. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine. 2006;160:876–882. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.160.9.876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Farb NA. Mind Your Expectations: Exploring the Roles of Suggestion and Intention in Mindfulness Training. The Journal of Mind–Body Regulation. 2012;2:27–42. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thayer JF, Friedman BH, Borkovec TD, Johnsen BH, Molina S. Phasic heart period reactions to cued threat and nonthreat stimuli in generalized anxiety disorder. Psychophysiology. 2000;37:361–368. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dix T. The affective organization of parenting: Adaptive and maladaptative processes. Psychological Bulletin. 1991;110:3–25. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.110.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Creswell JD, Way BM, Eisenberger NI, Lieberman MD. Neural correlates of dispositional mindfulness during affect labeling. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2007;69:560–565. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3180f6171f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bargh JA, Williams EL. The Automaticity of Social Life. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2006;15:1–4. doi: 10.1111/j.0963-7214.2006.00395.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Batson CD, Sager K, Garst E, Kang M, Rubchinsky K, Dawson K. Is empathy-induced helping due to self–other merging? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1997;73:495. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hölzel BK, Lazar SW, Gard T, Schuman-Olivier Z, Vago DR, Ott U. How Does Mindfulness Meditation Work? Proposing Mechanisms of Action From a Conceptual and Neural Perspective. Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2011;6:537–559. doi: 10.1177/1745691611419671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Siegel DJ. The mindful brain: Reflection and attunement in the cultivation of well-being. WW Norton & Co.; 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Salzberg S. Loving-kindness: The revolutionary art of happiness. Boston: Shambhala; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Coatsworth JD, Duncan LG, Greenberg MT, Nix RL. Changing Parent's Mindfulness, Child Management Skills and Relationship Quality With Their Youth: Results From a Randomized Pilot Intervention Trial. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2010;19:203–217. doi: 10.1007/s10826-009-9304-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Duncan LG, Coatsworth JD, Greenberg MT. Pilot Study to Gauge Acceptability of a Mindfulness-Based, Family-Focused Preventive Intervention. Journal of Primary Prevention. 2009;30:605–618. doi: 10.1007/s10935-009-0185-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Coatsworth JD, Duncan LG, Nix RL, Greenberg MT, Bamberger KT, Gayles JG, Demi MA. Integrating mindfulness with Parent Training: Effects of the Mindfulness-enhanced Strengthening Families Program. Manuscript submitted for publication. 2013 doi: 10.1037/a0038212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Collins WA, Steinberg L. Adolescent Development in Interpersonal Context. Social, emotional, and personality development. In: Eisenberg W, Damon W, Lerner R, editors. Handbook of Child Psychology. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 2006. pp. 1003–1067. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Greenberg MT, Harris AR. Nurturing mindfulness in children and youth: Current state of research. Child Development Perspectives. 2012;6:161–166. [Google Scholar]