Abstract

Objectives

To estimate the proportion of children who die with chronic conditions and examine time trends in childhood deaths involving chronic conditions.

Design

Retrospective population-based death cohort study using linked death certificates and hospital discharge records.

Setting

England, Scotland and Wales.

Participants

All resident children who died aged 1–18 years between 2001 and 2010.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

The primary outcome was the proportion of children who died with chronic conditions according to age group and type of chronic condition. The secondary outcome was trends over time in mortality rates involving chronic conditions per 100 000 children and trends in the proportion of children who died with chronic conditions.

Results

65.4% of 23 438 children (95% CI 64.8%, 66.0%) died with chronic conditions, using information from death certificates. This increased to 70.7% (95% CI 70.1% to 71.3%) if hospital records up to 1 year before death were also included and was highest (74.8–79.9% depending on age group) among children aged less than 15 years. Using data from death certificates only led to underascertainment of all types of chronic conditions apart from cancer/blood conditions. Neurological/sensory conditions were most common (present in 38.5%). The rate of children dying with a chronic condition has declined since 2001, whereas the proportion of deaths affected by chronic conditions remained stable.

Conclusions

The majority of children who died had a chronic condition. Neurological/sensory conditions were the most prevalent. Linkage between death certificate and hospital discharge data avoids some of the under-recording of non-cancer conditions on death certificates, and provides a low-cost, population-based method for monitoring chronic conditions in children who die.

Keywords: Paediatrics, Epidemiology

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This was a population-based study of all children who died, which minimised selection bias and allowed comparisons of the proportion who died with chronic conditions between age groups and over time.

Linkage between death certificates and hospital records avoided some of the under-recording of non-cancer chronic conditions on death certificates.

Standardised coding systems used in these linked databases allow for international comparisons in the proportion of children who die with chronic conditions.

This study was limited to linked hospital and death registration data. This means some children with chronic conditions managed mainly in primary care would be misclassified as not having a chronic condition.

Introduction

Steep declines in child mortality during the first half of the last century are attributed mainly to improved infant care, sanitation and diet.1 2 The decline since the 1950s3 reflects continued improvements in perinatal and infant care, and public health preventive policies such as better housing, clean air, immunisation programmes,4 traffic safety5 and use of better emergency care.6 Compared with 50 years ago, few previously healthy children now die from acute infections or injuries. At the same time, many children with conditions that were previously fatal in early childhood are now surviving much longer. Although neonatal and infant mortality rates have fallen among babies born preterm, there are concerns that the prevalence of neurodisability is increasing among survivors.7 8

This shift in survival of children with chronic and often complex conditions combined with more effective prevention of deaths in healthy children means that children with chronic conditions now make up an increasing proportion of childhood deaths.9 Policies to reduce child deaths therefore need to focus on preventable risk factors for death in children with chronic conditions, including the quality of their care.10 11 Also, some of these deaths will not be preventable, and there is a need to improve the quality of life and death for children and provide better support for their families.

Despite growing awareness of the importance of chronic childhood conditions resulting in death or intensive care,12 13 evidence on the proportion of child deaths affected by chronic conditions in the UK has been limited to conditions recorded on death certificates. In this report, we used data from the child's complete hospital discharge record linked to data from death certificates to determine the proportion of children who died with chronic conditions. Our study illustrates whole-country monitoring of chronic conditions in child deaths, which could be extended to international comparisons.

Methods

Defining chronic conditions

We characterised chronic conditions affecting the children who died. We did not attempt to infer whether the conditions contributed to death, as this is hard to deduce from records of children with multiple morbidities. In reporting what children died with, rather than what they died from, we aimed to inform policymakers about the most prevalent conditions in children who die, and indicate whether they are likely to have had contact with health services. Information on children who die with chronic conditions can indicate where in health services improvements in care might reduce mortality or lead to improvements in the quality of end-of-life care. Defining the conditions children die with also creates a framework that can be easily replicated in studies using linked administrative health data to examine, for example, the association between quality of care for children with particular chronic conditions and mortality.

We developed a definition of chronic conditions in children who die for use with longitudinal hospital discharge data linked to death certificates. We used a pragmatic definition of a chronic condition as any health problem likely to require follow-up for more than 1 year, where follow-up could be repeated hospital admission, specialist follow-up through outpatient department visits, medication or use of support services. This definition is broader than previously published definitions of chronic conditions in children, where the focus has been on the contribution of comorbidity to healthcare costs or to death.9 14 15

Using our definition of a chronic condition, we involved five clinicians in developing a code list (based on the International Classification of Diseases v.10 (ICD10)) to identify indices of chronic conditions recorded in death certificate and hospital administrative records16 (see online supplementary table S1). We included codes from validated code lists for chronic conditions in children9 17–22 and added further candidate codes based on searches of ICD10 and in electronic hospital discharge data.

We grouped the final list of ICD10 codes for chronic conditions into eight groups to ensure sufficient numbers of cases for analyses: mental/behavioural, cancer/blood, chronic infections, respiratory, endocrine/metabolic/digestive/renal/genitourinary (GU), musculoskeletal/skin, neurological/sensory and cardiac conditions (see online supplementary table S1). The groups were not mutually exclusive; that is, a child could have conditions from more than one group. We also included codes that identified children as having a chronic condition (eg, gastrostomy), but were not specific enough to classify into one of the eight groups (see online supplementary table S1). Children affected by multiple conditions were counted in each group for condition-specific analyses but were counted only once in the overall analyses.

Data sources

Our analyses are based on linkage of hospital discharge data to death certificates for all children resident in England, Scotland and Wales who died aged 1–18 completed years. Infants were excluded by the funders of the study. Summaries of the linked data sets and linkage methods can be found in online supplementary table S2.

We analysed deaths occurring between 2001 and 2010. However, deaths in Wales were included only from 2003 onwards (see online supplementary table S2). Because of delayed registration of death in England and Wales, we included all deaths that occurred before the end of 2010 that were registered up to August 2012.23 Details of data cleaning procedures are described elsewhere.16

Linkage between death certification and hospital discharge records was undertaken by the respective data providers in England, Scotland and Wales.16 Children with no evidence of a link between death certificates and hospital discharge records were assumed not to have been admitted to hospital in the period between the first available date from which linked hospital records were available and death.

We searched for any ICD10 codes indicating a chronic condition in all diagnostic fields in all hospital discharges from birth or from date when first available for a particular child until death and all causes mentioned on death certification records. All data in this study were anonymised, therefore ethics committee approval was not required (please see guidance from the National Health Service (NHS) Health Research Authority: http://www.hra.nhs.uk/documents/2013/09/does-my-project-require-rec-review.pdf).

Chronic conditions recorded in all children admitted to hospital

To provide a benchmark of the frequency of chronic conditions in hospitalised children using our indicator, we analysed all children admitted to hospital under the NHS in England between 2006 and 2010 aged 1–18 years old. We expected this proportion to be significantly lower in hospitalised children than among children who died. Using their most recent admission as the index, we determined the proportion of children with one or more chronic conditions recorded in their current or previous admissions during the preceding 12 months. This extract was provided by the Health and Social Care Information Centre.

Mid-year population estimates by age group were used as denominators for rates and obtained from the Office for National Statistics and National Records for Scotland.

Statistical analyses

We report results for the three countries combined. Differences between countries are reported in detail elsewhere.16 To illustrate the added value of linked longitudinal data, we determined the proportion of children who died with chronic conditions by type of condition and age group according to the amount of data from the child's hospitalisation trajectory. All children with a prior hospitalisation record have at least 1 year's linked hospital data available. However, admissions ending before the introduction of ICD10 coding are not included (see online supplementary table S2).16 We also calculated the proportion of children within each chronic condition group who had comorbid chronic conditions from other groups.

We estimated trends over time, by measuring the proportion of children who died with one or more chronic conditions in each calendar year. To determine the population burden of deaths with chronic conditions in children, we calculated annual death rates with mention of one or more chronic condition per 100 000 children. These analyses were based on linked hospital discharge data up to 1 year before death. We tested for a linear trend in the proportion of child deaths affected by at least one chronic condition at death by fitting logistic regression models to all child deaths where presence of at least one chronic condition at death was the outcome variable and year of death was the exposure variable. We repeated these analyses to examine trends in the proportion of children who had chronic conditions from two or more of the eight groups.

To test for trends in the rate of death per 100 000 children where chronic conditions were recorded, we fitted Poisson regression models (there was no evidence of overdispersion) with number of deaths as the outcome variable, year of death as the exposure variable and population size as an offset. For the regression models, a Wald test p value of the linear coefficient for year less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All models were fitted separately in each age group (1–4, 5–9, 10–14 and 15–18 years), and adjusted for sex of the child. Data management and statistical analyses were carried out in Stata/SE v.1124 and R v.3.1.0.25

Results

The study comprised death certificate data for 23 438 children resident in England and Scotland who died between 2001 and 2010, and Wales between 2003 and 2010. Death certification data for younger children, girls, Scottish residents and children who died later in the study period were more likely to be linked to a hospital record (see online supplementary table S3).

The proportion of child deaths affected by chronic conditions

Depending on the age group, between 57% and 76% of children who died had a chronic condition, based on codes recorded on death certificates, increasing to 67–83% when all the available hospital discharge data were used (table 1). The proportion of children with one or more chronic conditions was highest among children aged 5–14 years, yet the increase in this proportion, as increasing amounts of data from the hospital trajectory were included, was similar between age groups.

Table 1.

Proportion of children who died with one or more chronic conditions in England and Scotland (2001–2010) and Wales (2003–2010), by age group at death

| Data source (%) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Death certificate |

Death certificate and hospital discharge records |

|||||

| Age group | Underlying cause | Any condition mentioned | <30 days before death | <1 year before death* | <3 years before death | All available |

| Total (1–18 years) n=23 438 |

56.6 (56.0, 57.3) |

65.4 (64.8, 66.0) |

69.0 (68.4, 69.6) |

70.7 (70.1, 71.3) |

72.2 (71.6, 72.7) |

73.9 (73.3, 74.4) |

| 1–4 years n=5868 |

55.7 (54.4, 56.9) |

67.9 (66.7, 69.0) |

72.7 (71.5, 73.8) |

74.8 (73.7, 75.9) |

76.4 (75.3, 77.5) |

76.7 (75.6, 77.8) |

| 5–9 years n=3460 |

66.5 (64.9, 68.1) |

75.8 (74.3, 77.2) |

78.5 (77.1, 79.8) |

79.9 (78.5, 81.2) |

81.2 (79.9, 82.5) |

82.9 (81.6, 84.1) |

| 10–14 years n=4447 |

63.4 (61.9, 64.8) |

71.7 (70.3, 73.0) |

75.1 (73.8, 76.3) |

76.4 (75.1, 77.6) |

77.3 (76.1, 78.5) |

79.2 (77.9, 80.3) |

| 15–18 years n=9663 |

50.6 (49.6, 51.6) |

57.4 (56.4, 58.4) |

60.7 (59.7, 61.6) |

62.3 (61.3, 63.3) |

64.0 (63.0, 64.9) |

66.5 (65.5, 67.4) |

Bold typeface indicates the key outcome measure in the models.

*Note this is the outcome used in the regression models.

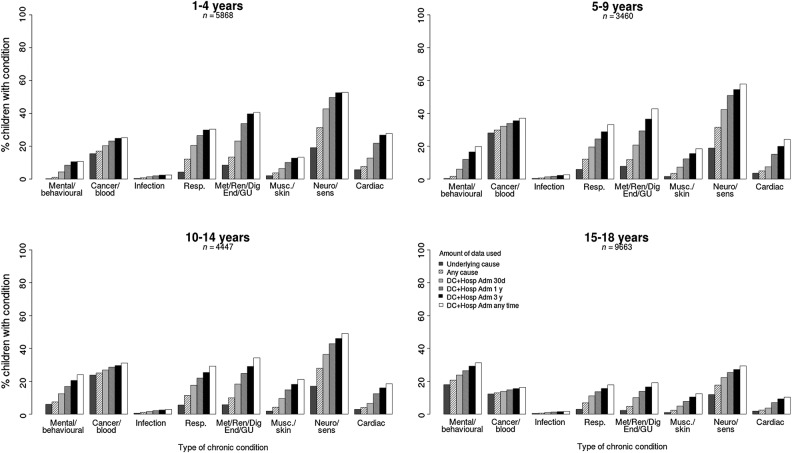

The amount of extra information gained by adding further data from the child's longitudinal healthcare trajectory varied according to the type of condition (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Proportion of children who died with each type of chronic condition according to the amount of data used from death certificates and longitudinal hospital records by age group.

If we considered only the underlying cause of death, cancer and blood disorders were the most common chronic conditions recorded (17.6% of child deaths aged 1–18 years; 4123 of 23 438 children). However, using linked hospital discharge records up to 1 year before death, the most common chronic conditions in children who died were neurological/sensory conditions (figure 1); 38.5% (9032 of 23 438) of children died with neurological/sensory conditions. 65.1% (5880 of 9032) of these children would have been identified if we included data from death certificates only.

Mental/behavioural conditions were the most prevalent chronic conditions in children aged 15–18 years, the age group with the largest number of deaths (figure 1). In this age group, 26.5% (2557 of 9663 children) died with a mental/behavioural condition using data from death certificates and hospital data up to 1 year before death; 78.1% of these children (1998 of 2557) could be identified from causes of death recorded on death certificates. In children younger than 15 years, adding data from hospital records up to 1 year before death led to between two (in 10–14-year-olds) and eight (in 1–4 year-olds) fold increase in the proportion of children who died with mental/behavioural disorders. For chronic infections, respiratory, metabolic/endocrine/renal/digestive/GU, musculoskeletal/skin and cardiac conditions only 31–49% of children, depending on the condition, would have been identified using death certificates compared with also using hospital records up to 1 year before death.

In total, 16 570 children had at least one chronic condition recorded on their death certificate or on linked hospital discharge records up to 1 year before death. 57.7% (9569 of 16 570 children) had chronic conditions from more than one group. A further 10 children were identified as having a chronic condition from non-specific codes only (eg, presence of gastrostomy or dependence on wheelchair). The proportion of children with conditions from two or more condition groups varied according to the type of chronic condition, being highest for children with musculoskeletal/skin conditions or chronic infections and lowest for children with mental/behavioural disorders (see online supplementary table S4).

Trends in the proportion of children who die with a chronic condition

There were significant increases in the proportion of children who died with one or more chronic conditions between 2001 and 2010 among children aged 5–9 years (increase from 77.8% to 83.9% of all deaths in this age group, Wald test p=0.007) and children aged 10–14 years (increase from 72.7% to 81.7% of all deaths in the age group, Wald test p=0.001). Rates remained stable in the other age groups (figure 2). In contrast, the proportion of children who died with conditions from two or more condition groups increased significantly in all age groups (Wald test p<0.001 in all age groups). These increases could be wholly accounted for by increases in the proportion of children who died with chronic conditions in England. No significant trends were observed in Scotland or in Wales in any age group (analyses not shown).

Figure 2.

Proportion of children who died with one or more chronic conditions or with conditions from two or more chronic condition groups, by age group at death and year of death.

Trends in child mortality rates involving chronic conditions

The overall rate of child deaths affected by chronic conditions per 100 000 children in the population declined over time (figure 3). These declines amounted to 2.4%, 3.1% and 4.2% per year in1–4, 10–14 and 15–18-year-olds, respectively and were statistically significant in all age groups apart from 5 to 9 years (Wald test p=0.10 for 5–9 year-olds, and p <0.001 for all other age groups). Declines were particularly evident for mental/behavioural conditions, cancer/blood conditions and neurological/sensory conditions (see online supplementary figure S1).

Figure 3.

Rate of deaths (per 100 000 children) with one or more chronic conditions (from death certificates or on hospital records up to 1 year before death) by age group and year of death.

The proportion of children admitted to hospital affected by a chronic condition

The proportion of children who died with chronic conditions was significantly higher than the proportion of children admitted to hospital who were affected by chronic conditions (table 2). Among hospitalised children, the proportion of children with a chronic condition increased with age.

Table 2.

Proportion of chronic conditions in children in England who died and in all children admitted to hospital in the NHS in England, 2006–2010

| Children who died in 2006–2010* Death certificates and hospital records |

Children who died in 2006–2010† Hospital records only |

All children hospitalised in the NHS in 2006–2010† |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age group | % n/N |

95% CI | % n/N |

95% CI | % n/N |

95% CI |

| 1–4 years | 76.3 1919/2516 |

(74.6 to 77.9) | 67.1 1688/2516 |

(65.2 to 68.9) | 24.4 208 186/853 557 |

(24.3 to 24.5) |

| 5–9 years | 82.9 1169/1410 |

(80.8 to 84.8) | 72.9 1028/1410 |

(70.5 to 75.2) | 27.9 179 862/645 047 |

(27.8 to 28.0) |

| 10–14 years | 78.7 1314/1669 |

(76.7 to 80.6) | 64.6 1078/1669 |

(62.3 to 66.8) | 28.1 158 425/563 504 |

(28.0 to 28.2) |

| 15–18 years | 61.2 2255/3686 |

(59.6 to 62.7) | 41.3 1522/3686 |

(39.7 to 42.9) | 32.0 257 877/805 046 |

(31.9 to 32.1) |

| Total | 71.3 6657/9281 |

(70.8 to 72.6) | 57.2 5316/9281 |

(56.3 to 58.3) | 28.1 804 350/2 867 154 |

(28.0 to 28.1) |

*Allowing for one year's data from hospital trajectory and death certificates.

†Allowing for one year's data from hospital trajectory.

NHS, National Health Service.

Discussion

Seventy-one per cent of children who died in England, Scotland and Wales had a chronic condition, most frequently a neurological/sensory condition. Fifty-eight per cent of children who died with chronic conditions were affected by two or more types of chronic conditions affecting different body systems. Adding data from hospital discharge records substantially increased the proportion of children who died with a chronic condition for all non-cancer/blood conditions and shifted the most prevalent condition from cancer/blood to neurological/sensory conditions. The mortality rate in children with chronic conditions declined over time in all age groups apart from children aged 5–9 years.

A key strength of this study was that the approach was based on administrative health data with population-based coverage, avoiding selection bias and allowing comparisons of patterns of chronic conditions and trends over time. Linkage to hospital discharge data avoids some of the underascertainment of non-cancer chronic conditions on death certificates.

We used a definition of chronic conditions based on internationally standardised coding, which lends itself to comparisons between countries on the role of chronic conditions in children who die. To validate our definition of chronic conditions, we compared the prevalence of chronic conditions in children who die and in all children admitted to hospital. Further studies are required to validate our definition in other settings, including in intensive care and primary care databases. This would also allow a more detailed examination of where in the NHS these children are being seen, and how often. Our classification was specifically designed to identify children with chronic conditions who required ongoing healthcare. In the future, comparisons between our approach and other classifications developed by Feudtner et al9 or the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality26 would guide choices about the most appropriate approach depending on the research question.

A key limitation of our study was the reliance on hospital discharge data. Linkage to general practice, community care and hospital outpatient databases would capture conditions such as asthma, diabetes and mental health conditions, which are most likely managed in these settings. This onward linkage would also allow further studies to examine, for example, the association between quality of care for children with mental illness and mortality.

As linked hospital discharge records build up over time, the proportion of death certificates in older children successfully linked to a hospital record will increase, reducing the risk of underestimating the prevalence of chronic conditions in older children. However, including many years of hospital data may overcount conditions which have resolved. This is why we focused analyses on linked hospital data up to 1 year before death.

Some deaths in children with chronic conditions may be preventable, but others are expected deaths. Distinguishing these groups is not possible using administrative data and requires more in-depth case-note reviews or qualitative studies.27

The prevalence of chronic conditions using our classification system was consistent with Feudtner et al9 (using their own classification), who reported a prevalence of 58.1% in children who died of medical causes aged 1–19 years in 1997 in the USA based on the underlying cause from the death certificate. Evidence of the importance of neurological conditions comes from studies of children needing intensive or end-of-life care. Edwards et al28 found that neuromuscular conditions were the most common type of complex chronic condition in children and young adults aged up to 21 years admitted to an intensive care unit in the USA, whereas Fraser et al20 found that congenital anomalies were the most common and neurological the third most common life-limiting conditions in England in children aged up to 19 years using hospital discharge data. Similar to Fraser et al, Ramnarayan et al13 found that the most common diagnoses recorded in paediatric intensive care audit data for children who died aged up to 18 years in intensive care at a tertiary paediatric hospital were congenital anomalies and perinatal conditions. None of these studies used a child's longitudinal hospital record to determine the presence and type of chronic conditions.

We identified declining trends in the population mortality rate involving chronic conditions. This finding was expected since all-cause mortality is declining in children in the UK.16 We also found evidence for an increase in the proportion of children who died with two or more different types of chronic conditions. This increase was observed for only England. This is partly due to the small number of deaths per year in Scotland and Wales. Another reason for the observed increase is that mortality due to infections and injuries in previously health children is decreasing, implying that a higher proportion of deaths will occur in children with chronic conditions. However, the increase may also reflect increasing coding depth in England. Under Payment by Results, a remuneration system for English NHS hospitals, which was introduced in 2004, hospitals are paid according to a formula determined by the surgical procedure carried out and the complexity of the diagnoses.29 While some hospitals have increased the number of codes recorded for each episode, fraudulent ‘overcoding’ has not been identified.30 Instead, increasing coding depth means that, over time, the prevalence of chronic conditions estimated using hospital databases approaches the true prevalence of chronic conditions. The number of diagnoses that could be entered per admission was also higher in England than in Scotland and increased over the study period (see online supplementary table S2). These changes in coding practice in English hospitals during the study period emphasise that thresholds for recording and coding need to be carefully considered when extending our approach to international comparisons.

We found that the proportion of hospitalised children in England increased with age, whereas the opposite was true for children who died. These differences may reflect the higher proportion of older children who die of injury,31 attrition as some children with chronic conditions die at a young age, and underascertainment of mental health problems, which are mainly managed in the community, in older children who died.

This study demonstrates how linked death records and hospital discharge databases can be used to examine trends and patterns of chronic conditions in children who die. This approach can be used for regular assessments of the role of chronic conditions in childhood mortality, and can be extended to other settings to further examine the use of health services by children who die.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors are very grateful to Dr Mike Sharland, Dr Katja Doerholt, Dr Quen Mok, Dr Andrew McArdle and Professor Peter Sidebotham for helping to develop the coding cluster for chronic conditions. They also gratefully acknowledge the Health and Social Care Information Centre, the Information Services Division of NHS Scotland and NHS Wales Informatics Services for providing the linked data for this study. The authors also acknowledge Ivana Pribramska for editorial support.

Footnotes

Collaborators : Members of the Working Group: Alison Macfarlane (City University), Sonia Saxena (Imperial College), Berit Müller-Pebody (Public Health England), Rachel Knowles (UCL Institute of Child Health), Roger Parslow (University of Leeds), Charles Stiller (University of Oxford), Anjali Shah (University of Oxford), Peter Sidebotham (University of Warwick), Jonathan Davey (UCL Institute of Child Health).

Contributors: RG conceptualised and designed the study, oversaw data analyses and contributed to drafting the final manuscript. PH carried out the data cleaning and analyses and drafted the final manuscript. ND negotiated access to data sources, contributed to data cleaning and analysis, and contributed to drafting the manuscript. All authors approved the final manuscript as submitted.

Funding: This study was part of the Child Health Reviews UK programme, which was commissioned by the Healthcare Quality Improvement Partnership (HQIP) on behalf of NHS England, NHS Wales, the Health and Social Care division of the Scottish government, The Northern Ireland Department of Health, Social Services and Public Safety (DHSSPS) the States of Jersey, Guernsey, and the Isle of Man. Members of the Project Programme Board were Neena Modi, Jennifer J Kurinczuk, Alan McMahon, John Thain, Jyotsna Vohra, Angela Moore. The study benefitted from infrastructure and academic support at the MRC Centre of Epidemiology for Child Health and the Farr Institute of Health Informatics Research @ UCL Partners.

Competing interests: None.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

Contributor Information

Collaborators: Alison Macfarlane, Sonia Saxena, Berit Müller-Pebody, Rachel Knowles, Roger Parslow, Charles Stiller, Anjali Shah, Peter Sidebotham, and Jonathan Davey

References

- 1.Mckeown T, Record RG, Turner RD. An interpretation of the decline of mortality in England and Wales during the twentieth century. Popul Stud (Camb) 1975;29:391–422 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centre for Disease Control and Prevention. Achievements in public health, 1900–1999: healthier mothers and babies. MMWR Surveill Summ 1999;48:849–58 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Viner RM, Coffey C, Mathers C, et al. 50-Year mortality trends in children and young people: a study of 50 low-income, middle-income, and high-income countries. Lancet 2011;377:1162–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Trotter CL, Ramsay ME, Kaczmarski EB. Meningococcal serogroup C conjugate vaccination in England and Wales: coverage and initial impact of the campaign. Commun Dis Public Health 2002;5:220–5 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roberts I. Why have child pedestrian death rates fallen. BMJ 1993;306:1737–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lecky F, Woodford M, Yates DW. Trends in trauma care in England and Wales 1989–97. UK Trauma Audit and Research Network. Lancet 2000;355:1771–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wilson-Costello D, Friedman H, Minich N, et al. Improved survival rates with increased neurodevelopmental disability for extremely low birth weight infants in the 1990s. Pediatrics 2005;115:997–1003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boyle CA, Boulet S, Schieve LA, et al. Trends in the prevalence of developmental disabilities in US children, 1997–2008. Pediatrics 2011;127:1034–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Feudtner C, Christakis DA, Connell FA. Pediatric deaths attributable to complex chronic conditions: a population-based study of Washington state, 1980–1997. Pediatrics 2000;106:205–9 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Confidential Enquiry into Maternal and Child Health. Why children die: a pilot study. 2008. http://www.injuryobservatory.net/documents/why_children_die1.pdf (accessed 30 Apr 2013).

- 11.Cohen E, Kuo DZ, Agrawal R, et al. Children with medical complexity: an emerging population for clinical and research initiatives. Pediatrics 2011;127:529–38 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Edwards P, Roberts I, Green J, et al. Deaths from injury in children and employment status in family: analysis of trends in class specific death rates. BMJ 2006;333:119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ramnarayan P, Craig F, Petros A, et al. Characteristics of deaths occurring in hospitalised children: changing trends. J Med Ethics 2007;33:255–60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Simon TD, Berry J, Feudtner C, et al. Children with complex chronic conditions in inpatient hospital settings in the United States. Pediatrics 2010;126:647–55 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cohen E, Berry JG, Camacho X, et al. Patterns and costs of health care use of children with medical complexity. Pediatrics 2012;130:E1463–70 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hardelid P, Dattani N, Davey J, et al. Overview of child deaths in the four UK countries. 2013. http://www.rcpch.ac.uk/system/files/protected/page/CHR-UK%20MODULE%20B%20REVISED%20v2%2015112013.pdf (accessed 8 Jan 2014).

- 17.Benchimol EI, Guttmann A, Griffiths AM, et al. Increasing incidence of paediatric inflammatory bowel disease in Ontario, Canada: evidence from health administrative data. Gut 2009;58:1490–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dart AB, Martens PJ, Sellers EA, et al. Validation of a pediatric diabetes case definition using administrative health data in Manitoba, Canada. Diabetes Care 2011;34:898–903 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.EUROCAT. EUROCAT Guide1.3 and referenced documents: Instructions for the Registration and Surveillance of Congenital Anomalies. 2005. http://www.eurocat-network.eu/content/EUROCAT-Guide-1.3.pdf (accessed 30 Apr 2013).

- 20.Fraser LK, Miller M, Hain R, et al. Rising national prevalence of life-limiting conditions in children in England. Pediatrics 2012;129:E923–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shah A, Diggens N, Stiller C, et al. Place of death and hospital care for children who died of cancer in England, 1999–2006. Eur J Cancer 2011;47:2175–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Steliarova-Foucher E, Stiller C, Lacour B, et al. International classification of childhood cancer, third edition . Cancer 2005;103:1457–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Devis T, Rooney C. The time taken to register a death. Popul Trends 1997;88:48–55 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.StataCorp. Stata 12. 2013. College Station, Texas: http://www.stata.com/accessed (20 May 2013). [Google Scholar]

- 25.R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. 2012. Vienna, Austria. http://www.R-project.org (accessed 20 May 2013).

- 26.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Chronic Condition Indicator (CCI) for ICD-9-CM. 2011. http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/toolssoftware/chronic/chronic.jsp (accessed 22 Apr 2013) [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Hogan H, Healey F, Neale G, et al. Preventable deaths due to problems in care in English acute hospitals: a retrospective case record review study. BMJ Qual Saf 2012;21:737–45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Edwards JD, Houtrow AJ, Vasilevskis EE, et al. Chronic conditions among children admitted to U.S. pediatric intensive care units: their prevalence and impact on risk for mortality and prolonged length of stay. Crit Care Med 2012;40:2196–203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jameson S, Reed MR. Payment by results and coding practice in the National Health Service. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2007;89B:1427–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Audit Commission. Payment by Results Assurance Framework. 2006. http://archive.audit-commission.gov.uk/auditcommission/subwebs/publications/corporate/publicationPDF/NEW1077.pdf (accessed 25 Apr 2013).

- 31.Hardelid P, Davey J, Dattani N, et al. Child deaths due to injury in the four UK countries: a time trends study from 1980 to 2010. PLoS ONE 2013;8:e68323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.