Abstract

Introduction

Postoperative pain control remains a major challenge for surgical procedures, including laparoscopic gastric bypass. Pain management is particularly relevant in obese patients who experience a higher number of cardiovascular and pulmonary events. Effective pain management may reduce their risk of serious postoperative complication, such as deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary emboli. The objective of this study is to evaluate the efficacy of intraperitoneal local anaesthetic, ropivacaine, to reduce postoperative pain in patients undergoing laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass.

Methods and analysis

A randomised controlled trial will be conducted to compare intraperitoneal ropivacaine (intervention) versus normal saline (placebo) in 120 adult patients undergoing bariatric bypass surgery. Ropivacaine will be infused over the oesophageal hiatus and throughout the abdomen. Patients in the control arm will undergo the same treatment with normal saline. The primary end point will be postoperative pain at 1, 2 and 4 h postoperatively. Pain measurements will then occur every 4 h for 24 h and every 8 h until discharge. Secondary end points will include opioid use, peak expiratory flow, 6 min walk distance and quality of life assessed in the immediate postoperative period. Intention-to-treat analysis will be used and repeated measures will be analysed using mixed modelling approach. Post-hoc pairwise comparison of the treatment groups at different time points will be carried out using multiple comparisons with adjustment to the type 1 error. Results of the study will inform the feasibility of recruitment and inform sample size of a larger definitive randomised trial to evaluate the effectiveness of intraperitoneal ropivacaine.

Ethics and dissemination

This study has been approved by the Ottawa Health Science Network Research Ethics Board and Health Canada in April 2014. The findings of the study will be disseminated through national and international conferences and peer-reviewed journals.

Trial registration number

Clinicaltrial.gov NCT02154763.

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The study will have an impact on the use of intraperitoneal local anaesthetic (IPLA) in laparoscopic gastric bypass surgery. A positive finding would confirm the effectiveness of IPLA in laparoscopic gastric bypass surgery. Negative results may lead to changes to the current postoperative management practices and prompt further research to improve pain management following laparoscopic gastric bypass.

This will be the first study to evaluate intraperitoneal Ropivacaine in bariatric gastric bypass surgery.

The study is a single centre study. Patients will be subject to standardised intraoperative anaesthetic use and postoperative surgical pathway. Generalisability of the study will depend on the practice of individual institution.

Introduction

Management of postoperative pain remains a major challenge. Effective pain control encourages early ambulation, which significantly reduces the risk of deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary emboli (PE); enhances patient's ability to take deep breaths to decrease the risk of pulmonary complications (eg, atelectasis and pneumonia); and decreases the incidence of tachycardia and unnecessary related investigations.

The obesity epidemic has led to a significant rise in the need for surgical intervention. This recent phenomenon further highlights the importance of understanding the analgesic requirements of the bariatric patient. Pain management is particularly relevant in the obese population given their higher susceptibility for serious perioperative complications from cardiovascular, thromboembolic and pulmonary events. These include a high prevalence of obstructive sleep apnoea, hypoxia, respiratory depression and PE, which is the second leading cause of death among bariatric surgery patients.1

A number of strategies exist for controlling postoperative pain. One such method, intraperitoneal local anaesthetic (IPLA), involves the infusion of local anaesthetic into the abdomen during surgery. This procedure has been extensively studied in general surgery and gynaecology.2–6 Two systematic reviews have investigated the effectiveness of IPLA as a method of reducing postoperative pain and opioid consumption.7 8 Although the timing of IPLA administration varied between included studies (ie, at predissection or postdissection), evidence overwhelmingly supports pre-emptive IPLA9–11 as it blocks the afferent nerves in the peritoneum before surgical trauma.

Ropivacaine, a newer analgesic, with a better toxicity profile compared with alternatives such as bupivacaine, is currently considered the safest long-acting local anaesthetic in the market.12 Two trials comparing the plasma concentration after intravenous use of ropivacaine versus bupivacaine have demonstrated that ropivacaine requires a higher plasma concentration before toxicity develops.8 13 Importantly as an IPLA, ropivacaine has been shown to be effective at reducing pain without clinical toxicity.14–18 Despite promising results, there is still a paucity of studies that have specifically focused on the use of IPLA in the bariatric surgery population.19–22 To our knowledge, Our INtraperitoneal rOPivAcaINe in bariatric surgery (INOPAIN) study is the first trial examining the use of ropivacaine in the setting of obesity surgery. Our objective is to evaluate the efficacy of ropivacaine as an IPLA to reduce postoperative pain in patients undergoing laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery (LRYGB).

Methods and analysis

Design

The study recruitment began on 3 July and is expected to last 6 months to 31 December 2014. This pilot trial is a double-blind, randomised, controlled parallel arm study. Participants, the clinical care team (surgeon and nurses) and outcome assessors will all be concealed from allocation and blinded during the trial. The pilot study will assess the feasibility of a larger definitive study.

Setting and participants

Participants will be recruited from the Ottawa Civic Hospital, an academic centre serving a catchment area of 1.3 million residents in Eastern Ontario (Ottawa and environs), Canada. LRYGB is the standard operation for obesity in Canada. Patients will be treated by one of three participating expert surgeons (JM, JDY or AN) who routinely perform LRYGB.

Eligible participants will be adults undergoing LRYGB for obesity who are able to tolerate general anaesthetic and pneumoperitoneum, and provide informed consent for the surgery. Patients with chronic pain requiring preoperative opioids will be included. Exclusion criteria are: (1) patients undergoing planned sleeve gastrectomy (intraoperative conversion to sleeve gastrectomy after IPLA delivery will be included and analysed using intention-to-treat approach); (2) allergy to local anesthetics; (3) severe underlying cardiovascular disease, including congestive heart failure, conduction abnormalities, and ischaemic heart disease; (4) chronic renal disease stage 3 or higher (defined as creatinine clearance less than 60 mL/h); (5) hepatic dysfunction Child-Pugh class B or C and (6) previous foregut surgery, including oesophageal, gastric, liver and pancreas resections.

Recruitment

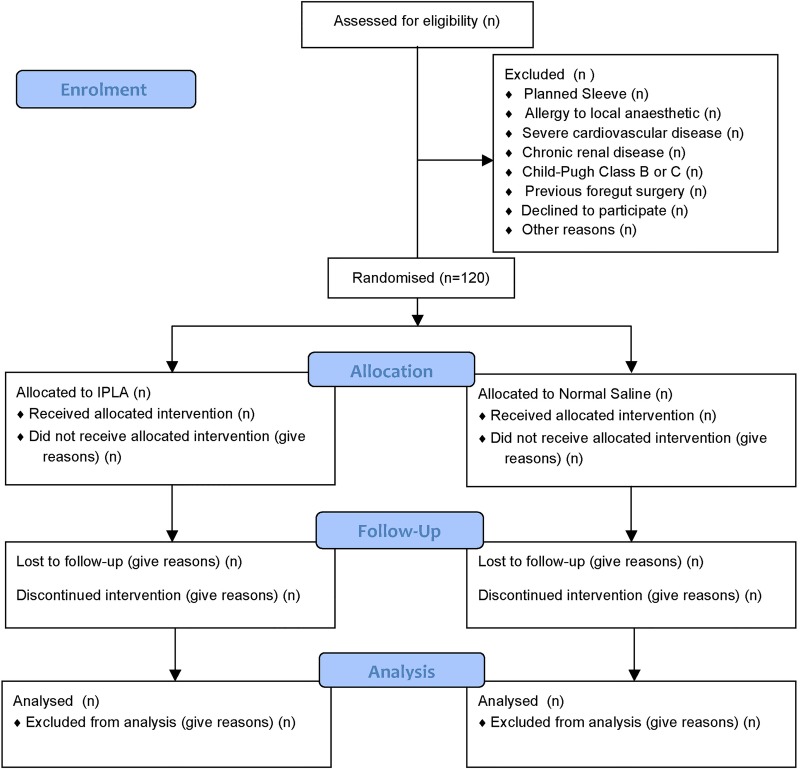

Eligible participants will initially be identified by a participating surgeon or a nurse from the Ottawa Hospital Bariatric Surgery Clinic. If the patient agrees to participate, consent will be obtained by a research assistant (RA), who is independent from the clinical care of patients. The study flow will be shown according to the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) flow chart (figure 1). Baseline data will be captured by the surgeon at the time of enrolment into trial.

Figure 1.

CONSORT flow diagram of the INOPAIN study. Source: Moher et al29 (IPLA, intraperitoneal local anaesthetic).

Randomisation

Participants will be randomised using a computerised simple randomisation scheme in a 1:1 ratio to intervention and control arms. Randomisation will be performed on the day prior to surgery to allow for the preparation of medication by the department of pharmacy. Surgeries booked on Monday will be randomised on Friday.

Allocation concealment

Once randomised, the pharmacy will independently prepare the treatment solution (ropivacaine or normal saline (NS)) in a standardised 100 mL bag. The treatment solution will be attached a patient's unique identifier and will not indicate to which arm the patient is allocated. Intravenous bags will be labelled according to Health Canada regulations and will not disclose content contained in the bag. The treatment medication will be delivered to the operating room on the day of surgery.

Blinding

All parties, including the patients, surgeons, clinic/OR/floor unit nurses will be blinded to treatment arm. If emergency unblinding is required (at the discretion of the investigator), a request to the on-call pharmacy research technician will be made in order to determine the patient treatment regimen. If unblinding occurs, the event will be recorded in the patient's chart and study file with the corresponding reason for unblinding.

Interventions

Study participants will be randomised into two parallel arms. The patients assigned to the intervention arm will receive the following treatment:

The trocars will be placed in the abdomen in the usual manner. All patients will receive a total of 100 mL of 0.2% ropivacaine. Using a standard suction/irrigation device and tubing, 200 mg total of ropivacaine in 100 mL NS will be instilled into the abdomen prior to surgical dissection. Under direct visualisation, 50 mL will be delivered over the oesophageal hiatus. The remaining 50 mL will be infused throughout the abdomen. The infusion line will then be flushed with 30 mL of NS to ensure any residual ropivacaine is delivered. The remainder of the surgery will proceed as usual. Patients assigned to the control arm will only receive intraperitoneal NS with the same delivery procedure.

The effect of irrigation and suction is unlikely to impact the absorption of ropivacaine unless the infused fluid is suctioned immediately. It has a high absorption constant and is rapidly taken up systemically.23 There is ample research support for the pre-emptive delivery of anaesthetic prior to dissection.9–11 The intraperitoneal absorption of ropivacaine and plasma concentration has been studied and shown to have low-toxicity potential where the peak concentration was much less (1.14 μg/mL) than the maximum tolerable level of 2.2 mg/L.24 To ensure operator compliance, each delivered package to the operating theatre will be checked to ensure all assigned medication was delivered.

Patients in both arms will receive standardised anaesthetic protocol for induction and maintenance. Induction anaesthetic would only include fentanyl boluses for pain, ketamine or propofol for sedation, and rocuronium or succinylcholine for neuromuscular blockade. For general anaesthesia maintenance, dexmedetomidine and fentanyl boluses are to be used. Dexamethasone and ondansetron will be used as intraoperative antiemetics. No long-acting opioids will be used preoperatively or intraoperatively. Postoperatively, patients will receive breakthrough pain medication, as necessary, including morphine, hydromorphone and acetaminophen. All participants will undergo the bariatric surgery clinical pathway.

Outcome assessment

Baseline data will include patient demographics and their existing comorbidities, medical and surgical history, medications, allergies and social history including smoking, alcohol and drug use. Pain history of fibromyalgia, back pain and arthritis will be documented. The patient will also be asked to complete a quality of recovery questionnaire (QR-40) and a 6 min walk test.

Feasibility measures and the decision to proceed with the definitive trial will be determined by number of eligible patients, rates of recruitment, randomisation, data completion and quality, patient retention and cost-related data collection. The required sample size for a definitive trial will be calculated using the clinical outcome data from the pilot trial. The pilot study will be deemed feasible if the number of eligible, randomised and retained cases within the pilot trial generate the required sample size within a 12 month period of recruitment. A more than 60% recruitment of those eligible will be seen as acceptable and 90% as satisfactory.

Efficacy end point

The data collection and questionnaires to be administered in the pilot trial are those proposed for the definitive trial. The primary efficacy end point is postoperative pain score, as measured by the visual analogue scale, which has been extensively validated in pain management. Changes between 13–16 mm are widely accepted as clinically relevant.25

The secondary efficacy end points include: (1) opioid use, as measured by total opioid consumption. The quantity and route of opioid medication delivery will be captured and converted to morphine equivalent for comparison. Opioid use has been evaluated in other studies where IPLA was used. Some evidence indicate IPLA may significantly reduce the consumption of opioid.19 Acetaminophen will be administered orally and overall consumption will be captured. (2) Peak expiratory flow (PEF), as measured by the incentive spirometry. PEF has not been studied in obese patients. There is no recommendation on a clinically significant change. (3) A 6 min walking distance (6 MWD), defined as the distance (in metres) an individual is able to walk along a flat 30 m walkway over a 6 min period, with breaks as required. Walk testing has been validated in the obese population. Clinically significant differences occur at a minimum of 80 m.26

Pain scores will be measured at baseline, immediately in recovery, at 1, 2 and 4 h postoperation and then every 4 h for 24 h, then every 8 h up to a maximum of 48 h postoperation. Opioid consumption will be measured immediately after the surgery, then at 1, 2, 4, 12, 24 and then 48 h or sooner if patient is discharged earlier. PEF scores will be measured at baseline, immediately in recovery and then every 4 h for a period of 24 h, then every 8 h up to a maximum of 24 h postsurgery. Six MWD will be measured at the baseline, on postoperative days 1 and 2 and at follow-up clinic within 10 days of operation.

Explanatory end point

Quality of life as measured by the QR-40 will be measured. It is a validated instrument that was developed specifically for postoperative patients.27

QR-40 scores will be recorded at baseline, prior to discharge and at clinic follow-up within 10 days of discharge.

Study flow

An overview of planned data collection is demonstrated in table 1.

Table 1.

INOPAIN study flow

| Preoperative education class | Clinic visit with surgeon | Preoperative admit unit | Operating room | Postoperative anaesthetic unit | Bariatric floor | Follow-up clinic | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Informed consent | X | ||||||

| Study eligibility confirmation | X | ||||||

| Demographic data | X | ||||||

| Medical and surgical history | X | ||||||

| Height, weight and BMI | X | ||||||

| 6 min walk distance | X | X | X | ||||

| Quality of recovery 40 | X | X | X | ||||

| Pain | X | X | X | ||||

| Peak expiratory flow | X | X | X | ||||

| Intraoperative anaesthetic use | X | ||||||

| Intraoperative adverse events and procedures | X | ||||||

| Postoperative pain medication use | X | X | |||||

| Postoperative events | X |

BMI, body mass index.

Sample size

There is relatively little information on the distribution of pain scores, health-related quality of life scores or on recruitment and retention rates in the obese patient population. The main purpose of the proposed pilot trial is to define the distribution in outcome measures, as well as the feasibility of recruiting and retaining patients for a more definitive trial.

The sample size for pilot trials is typically determined pragmatically, with recommendations of 30–60 participants per arm. Based on a loss to follow-up of 10% with 95% CI of 12.7% to 16.3%, we anticipate a recruitment rate of 33–38 patients/month to a total of 120 participants within a 4-month recruitment period.

Rescue medication and risk management

The organisation, monitoring and quality assurance will be under the responsibility of the principal investigator.

Peak serum concentration of ropivacaine occurs 30 min after instillation15 and decreases thereafter. Patients will receive standard cardiorespiratory monitoring, temperature and neuromuscular monitoring throughout the procedure. Gastric bypass typically takes 2–3 h and therefore patients will have close clinical observation during the expected peak concentration times. In accordance with the American Society of Regional Anesthesia28 recommendations, patients in the study will be monitored with continuous ECG from the time of administration for the first 24 h. Patients who develop signs of toxicity will receive prompt and immediate standard advanced cardiac life support (ACLS)-guided resuscitation and advanced airway management. Depending on their presentation, they may require seizure suppression, cardioprotective strategies with antiepileptics, or 20% lipid emulsion (Intralipid). These drugs and the ability to provide cardiorespiratory support are both available in the PACU.

Discontinuation criteria

Early withdrawal of participants will be initiated by research staff if:

Mechanical complications occur during surgery that are unrelated to the treatment but that may confound postoperative outcomes, for example, intraoperative haemorrhage, larger spillage of bowel contents, iatrogenic injuries, conversion to laparotomy, etc.

Patients are unwilling to follow investigators’ instructions.

As the Data Safety monitoring Board (DSMB) conducts ongoing review of safety data, the investigators may prematurely stop the study in its entirety due to toxicity at the recommendation of DSMB.

Data safety monitoring

An independent DSMB will be established prior to the randomisation of the first patient. The DSMB is an external independent group which included at least one expert in trial methodology, anaesthesiology and/or bariatric surgery. The DSMD will perform ongoing review of safety and efficacy data to minimise exposure of patients to unsafe therapy or dose, make recommendations for changes in the study processes where appropriate, advise on the need for dose adjustment for safety issues and endorse study continuation.

The sponsoring organisation, the Ottawa Health Research Institute (OHRI), will also internally audit the trial conduct at the beginning and every 3 months during the trial.

Data collection and analysis plan

RA will collect majority of the data and nurses on the bariatric floor and will also help collect pain score and PEF while patients are recovering in the bariatric unit. Nurse educator, nursing unit coordinator in the relevant hospital units have been informed and trained for the study. RAs have been trained by the sponsoring OHRI on accuracy and consistency of data collection.

The primary and secondary efficacy analysis will be based on the assigned treatment of patients (intention-to-treat analysis). Efficacy measures will be analysed using a mixed modelling approach to account for the dependence between measurements taken over time from the same patient. The comparison of the treatment arms for the efficacy end points will be conducted at a two-sided significance level of 0.05. Post-hoc pairwise comparison of the treatment arms at different time points will be carried out using multiple comparisons with adjustment to the type 1 error rate. No interim analysis is planned for this study.

QR-40 will be analysed by various cross-tabulations, CIs and proper graphical displays. Parametric and non-parametric correlation coefficients scatter plots and box-and-whisker plots will be studied. Measurements over time will be summarised at each interval. QR-40 over time will be compared between treatment arms.

Outcome assessors involved in the measuring and collecting of study end points will be blinded to the intervention.

The trial data will be housed on the OHRI network and will only be accessible to the study investigators and RAs on request.

Safety

Safety end points are:

Serious adverse event (SAE) rates—defined as the fraction of participants with an SAE.

Surgical complication rates—defined as the fraction of participants with a surgical complication.

Anticipated SAEs include the risks of an anaesthetic, bleeding, wound infection, bowel injury, unexpected leak, pneumothorax, obstruction and general complications such as a thromboembolic events, pneumonia, cardiac events and stroke. As per current protocol, patients will be contacted by a nurse practitioner the day following discharge to ensure they are coping at home. Patients will also be instructed to contact the clinical research team at any time after consenting to join the trial if they have an event that requires hospitalisation or results in persistent or significant disability or incapacity. Ropivacaine is well tolerated and has been studied in the management of other surgical patients. SAE are not anticipated in this study.

Safety analysis

The safety efficacy analysis will be based on the treated population. Participants will be included in the analysis according to the treatment received.

SAE will be mapped to preferred terms and system organs class using the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (MedDRA). The incidence of participants with a study drug-related SAEs will be summarised by treatment group according to preferred term and system organ class. Information regarding the occurrence of surgical complication events will be recorded on specific case report forms (CRFs). SAEs rate will be summarised based on the crude proportion of participants with one or more SAEs at the time of final analysis. Pearson χ2 test performed at the 0.05 level, stratified by treatment groups, will be used to compare SAE rates.

Surgical complication will be classified according to the Clavien-Dindo classification (http://www.surgicalcomplication.info/index-2.html). Complication event rates will be summarised based on the crude proportion of participants with one or more complication events. Pearson χ2 test performed at the 0.05 level, stratified by treatment groups, will be used to compare events rates based on severity (grade ≥3 vs grade <3).

Reporting of safety results

Investigators will report all unanticipated problems (ie, unexpected, related/possibly related and increased risks of harm) to the Ottawa Health Science Network Research Ethics Board (OHSN-REB) within 7 days of the incident or after the investigator becomes aware of the event in accordance with REB SOP OH1003—Safety Reporting Requirements for Research Involving Human Participants.

The investigators will report all SAEs to the DSMB Chair by email within seven calendar days after the investigators become aware of the event. A written report will be sent to the DSMB within 15 calendar days.

The investigators will also determine if the SAE is unexpected and related/possibly related for ropivacaine. An unexpected event for a ropivacaine is defined as any event not listed in the drug package insert. If the investigators determine that any study-related SAE is unexpected for a ropivacaine, Health Canada will be notified within seven calendar days.

Ethics and dissemination

The OHSN-REB has approved the study and all participants provided informed consent. All changes to the trial protocol are required to be approved by the OHSN-REB.

Only the study RAs and individuals in the patient's circle of care will have access to patient information.

The study results will be made publically available through local, national and international conferences, as well as peer-reviewed journals.

Discussion

Outcomes of this pilot trial will determine the feasibility of a larger randomised controlled trial. Recruitment rates, logistics of randomisation, treatment allocation and data acquisition will all be used to assess the feasibility of the definitive study. Improvement of postoperative pain management offers great benefit to patient care and quality of life. It provides surgeons and anaesthesiologists with further opportunity to improve patient comfort and; reduce complications, reduce length of stay and healthcare costs. On the other hand, if our study finds evidence to indicate equivalence between IPLA and control arms in postoperative pain control, the already established use of ropivacaine by many clinics in North America and Europe, would be challenged.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Hadi Mehrzad Namazi for helping with the database creation of the study. The authors thank Dong Vo of the Ottawa Health Research Institute for creating the randomisation scheme and database for the trial.

Footnotes

Contributors: RW made contributions to study design, was involved in coordinating and overseeing the trial, and drafted the manuscript. FH made substantial contributions to conception and design, was involved in coordinating the trial and writing and revising the manuscript. NP and NE made substantial contributions to the conception and design and were also involved in organising the trial. IR, JDY and AN were involved in organising the trial and were also involved in revising the manuscript. TR made significant contributions to study design and statistical analysis. JM made contributions to study design, was involved in overseeing the trial, revising the manuscript and has given the final approval of the version to be published.

Funding: This work was supported by The Ottawa Hospital Department of Surgery Research Grant [LBLB 7171609017].

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: The Ottawa Health Science Network Research Ethics Board.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Fernandez AZ, Demaria EJ, Tichansky DS, et al. Multivariate analysis of risk factors for death following gastric bypass for treatment of morbid obesity. Ann Surg 2004;239:698–703 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Narchi P, Benhamou D, Fernandez H. Intraperitoneal local anaesthetic for shoulder pain after day-case laparoscopy. Lancet 1991;338:1569–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bisgaard T, Klarskov B, Kristiansen VB, et al. Multi-regional local anesthetic infiltration during laparoscopic cholecystectomy in patients receiving prophylactic multi-modal analgesia: a randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled study. Anesth Analg 1999;89: 1017–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.El-Sherbiny W, Saber W, Askalany AN, et al. Effect of intra-abdominal instillation of lidocaine during minor laparoscopic procedures. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2009;106:213–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kang H, Kim B-G. Intraperitoneal ropivacaine for effective pain relief after laparoscopic appendectomy: a prospective, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Int Med Res 38:821–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kahokehr A, Sammour T, Shoshtari KZ, et al. Intraperitoneal local anesthetic improves recovery after colon resection: a double-blinded randomized controlled trial. Ann Surg 2011;254:28–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boddy AP, Mehta S, Rhodes M. The effect of intraperitoneal local anesthesia in laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Anesth Analg 2006;103:682–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marks JL, Ata B, Tulandi T. Systematic review and metaanalysis of intraperitoneal instillation of local anesthetics for reduction of pain after gynecologic laparoscopy. J Minim Invasive Gynecol 2012;19:545–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pappas-Gogos G, Tsimogiannis KE, Zikos N, et al. Preincisional and intraperitoneal ropivacaine plus normal saline infusion for postoperative pain relief after laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a randomized double-blind controlled trial. Surg Endosc 2008;22:2036–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gupta A. Local anaesthesia for pain relief after laparoscopic cholecystectomy—a systematic review. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol 2005;19:275–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bisgaard T. Analgesic treatment after laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a critical assessment of the evidence. Anesthesiology 2006;104:835–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Graf BM. The cardiotoxicity of local anesthetics: the place of ropivacaine. Curr Top Med Chem 2001;1:207–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Knudsen K, Beckman Suurküla M, Blomberg S, et al. Central nervous and cardiovascular effects of i.v. infusions of ropivacaine, bupivacaine and placebo in volunteers. Br J Anaesth 1997;78:507–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Callesen T, Hjort D, Mogensen T, et al. Combined field block and i.p. instillation of ropivacaine for pain management after laparoscopic sterilization. Br J Anaesth 1999;82:586–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Labaille T, Mazoit JX, Paqueron X, et al. The clinical efficacy and pharmacokinetics of intraperitoneal ropivacaine for laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Anesth Analg 2002;94:100–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kucuk C, Kadiogullari N, Canoler O, et al. A placebo-controlled comparison of bupivacaine and ropivacaine instillation for preventing postoperative pain after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surg Today 2007;37:396–400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Park YH, Kang H, Woo YC, et al. The effect of intraperitoneal ropivacaine on pain after laparoscopic colectomy: a prospective randomized controlled trial. J Surg Res 2011;171:94–100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cha SM, Kang H, Baek CW, et al. Peritrocal and intraperitoneal ropivacaine for laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a prospective, randomized, double-blind controlled trial. J Surg Res 2012;175:251–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Symons JL, Kemmeter PR, Davis AT, et al. A double-blinded, prospective randomized controlled trial of intraperitoneal bupivacaine in laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. J Am Coll Surg 2007;204:392–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Alkhamesi NA, Kane JM, Guske PJ, et al. Intraperitoneal aerosolization of bupivacaine is a safe and effective method in controlling postoperative pain in laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. J Pain Res 2008;1:9–13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sherwinter DA, Ghaznavi AM, Spinner D, et al. Continuous infusion of intraperitoneal bupivacaine after laparoscopic surgery: a randomized controlled trial. Obes Surg 2008;18:1581–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rodriguez L. Intraperitoneal analgesia compared with levobupivacaine 0.25% versus saline in laparoscopic bariatric surgery: 14AP5-11. Eur J Anaesthesiol 2011;28:203 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Betton D, Greib N, Schlotterbeck H, et al. The pharmacokinetics of ropivacaine after intraperitoneal administration: instillation versus nebulization. Anesth Analg 2010;111:1140–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maestroni U, Sortini D, Devito C, et al. A new method of preemptive analgesia in laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surg Endosc 2002;16:1336–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gallagher EJ, Bijur PE, Latimer C, et al. Reliability and validity of a visual analog scale for acute abdominal pain in the ED. Am J Emerg Med 2002;20:287–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Larsson UE, Reynisdottir S. The six-minute walk test in outpatients with obesity: reproducibility and known group validity. Physiother Res Int 2008;13:84–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Myles PS, Weitkamp B, Jones K, et al. Validity and reliability of a postoperative quality of recovery score: the QoR-40. Br J Anaesth 2000;84:11–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.ATS Committee on Proficiency Standards for Clinical Pulmonary Function Laboratories. ATS statement: guidelines for the six-minute walk test. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2002;166:111–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moher D, Schulz KF, Altman D. The CONSORT statement: revised recommendations for improving the quality of reports of parallel-group randomized trials. JAMA 2001;285:1987–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.