Abstract

Objectives

To characterise the mRNA expression patterns of early and advanced stage colorectal adenocarcinomas of Malaysian patients.

Design

Comparative expression analysis.

Setting and participants

We performed a combination of annealing control primer (ACP)-based PCR and reverse transcription-quantitative real-time PCR for the identification of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) associated with early and advanced stage primary colorectal tumours. We recruited four paired samples from patients with colorectal cancer (CRC) of Dukes’ A and B for the preliminary differential expression study, and a total of 27 paired samples, ranging from CRC stages I to IV, for subsequent confirmatory test. The tumouric samples were obtained from the patients with CRC undergoing curative surgical resection without preoperative chemoradiotherapy. The recruited patients with CRC were newly diagnosed with CRC, and were not associated with any hereditary syndromes, previously diagnosed cancer or positive family history of CRC. The paired non-cancerous tissue specimens were excised from macroscopically normal colonic mucosa distally located from the colorectal tumours.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

The differential mRNA expression patterns of early and advanced stage colorectal adenocarcinomas compared with macroscopically normal colonic mucosa were characterised by ACP-based PCR and reverse transcription-quantitative real-time PCR.

Results

The RPL35, RPS23 and TIMP1 genes were found to be overexpressed in both early and advanced stage colorectal adenocarcinomas (p<0.05). However, the ARPC2 gene was significantly underexpressed in early colorectal adenocarcinomas, while the advanced stage primary colorectal tumours exhibited an additional overexpression of the C6orf173 gene (p<0.05).

Conclusions

We characterised two distinctive gene expression patterns to aid in the stratification of primary colorectal neoplasms among Malaysian patients with CRC. Further work can be done to assess and compare the mRNA expression levels of these identified DEGs between each CRC stage group, stages I–IV.

Keywords: PUBLIC HEALTH

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This regional-based study has a relatively small sample size due to the lack of a designated Tissue Bank and colorectal cancer (CRC) patient volunteers.

All subjects were newly diagnosed with CRC, and were not associated with any hereditary syndromes, previously diagnosed cancer or positive family history of CRC.

The findings of this study are considered preliminary.

Introduction

Cancer staging is vital for patient management, especially in prognosis prediction and planning of treatment intervention.1 This is especially so in the colorectal cancer (CRC) staging system. As such, there have been many noteworthy improvements since the introduction of the classical Dukes’ staging system, followed by the modified Astler-Coller staging system; to the latest seventh edition of tumour-node-metastasis (TNM) staging system published by the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC).2–4 The TNM staging system allows the incorporation of various clinical information (which are obtained through histopathological examination, radiological imaging and surgical findings), for accurate CRC stratification.5 However, these clinical assessments are greatly dependent on the expertise of pathologists, radiologists and clinicians.

The TNM classification is applicable for both clinical (cTNM) and pathological (pTNM) staging of primary colorectal tumours. Typically, it involves the assessment on the depth of bowel wall invasion at the time of diagnosis and the presence of regional lymph nodes metastases, as well as the presence of distant organ metastasis.4 As a potentially worse patient outcome with more advanced disease stage is the core concept in cancer staging, AJCC revises the TNM classification system every few years with an attempt to formulate it for more accurate patient prognostication.5 The latest seventh edition has further detailed the subclassification of the pN category and the assessment of discontinuous/satellite tumour foci. However, these revisions have increased the complexity and subjectivity during evaluation, and thus might lead to interobserver variability and hamper its efficiency in routine clinical practise.5 6 In addition, current clinicopathological parameters are insufficient to address the great biological and genetic heterogeneity of CRC in patients’ outcome and treatment response prediction. From the perspective of clinical oncology, the integration of molecular biomarkers into existing clinicopathological assessment will further refine the cancer management in future.

Over the past decades, many researchers have attempted to establish gene expression signatures specifically for the diagnosis, prognostication and recurrence prediction of sporadic CRC. Transcriptional profiling promises a fairly dynamic view on the cellular functions, regulatory mechanisms and biochemical pathways involved in the disease pathogenesis and progression.7 Various gene expression profiling techniques ranging from differential display, SAGE to microarrays, have been utilised. Despite its wide application in gene expression profiling, microarray experiments have been subjected to various sources of variability, false-positives as well as statistical and bioinformatic challenges. To date, none of the molecular markers described has been validated and employed in routine clinical practise owing to the poor reproducibility of the identified differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between different profiling platforms.8 Although the KRAS mutation and mismatch repair status have shown promising prognostic and predictive values, they have yet to be incorporated into either routine pathological reporting systems or TNM staging systems.5

As most of the molecular studies on CRC were based in Western populations and different molecular changes were thought to underlie the development of sporadic CRC in populations with different genetic backgrounds, we aimed to investigate the changes in mRNA expression patterns in primary sporadic colorectal tumours with regard to our Malaysian patients. In our study, we employed a combined approach of a two-step ACP-based PCR and real-time reverse transcription PCR to characterise the gene expression patterns for early and advanced stage sporadic colorectal adenocarcinomas.

Materials and methods

Patient selection and specimen collection

All patients presented with histologically confirmed colorectal adenocarcinomas and were staged accordingly to the AJCC TNM staging system (table 1). The staging of cancer was performed by taking into consideration their histopathological reports, CT images, morphological evaluations during surgery and serum carcinoembryonic antigen levels. All patients were newly diagnosed with CRC, and were not associated with any hereditary syndromes, previously diagnosed cancer or positive family history of CRC. Initially, four patients with CRC stages I–III were recruited for the preliminary ACP-based PCR analysis, while another 27 patients with CRC stages I–IV were recruited for subsequent reverse transcription-quantitative real-time PCR (RT-qPCR) analysis. The patients’ group was composed of the three main ethnic groups in the Malaysian population, that is, Chinese, Malays and Indians, in order to ensure a better representative of the study population.

Table 1.

Cancer staging of recruited subjects

| Subject | Cancer stage |

|---|---|

| T1 | Stage I/pT1N0M0 |

| T2 | Stage II/pT3N0M0 |

| T3 | Stage II/pT2N0M0 |

| T4 | Stage II/pT3N0M0 |

| T5 | Stage II/pT3N0M0 |

| T6 | Stage II/pT4N0M0 |

| T7 | Stage II/pT4N0M0 |

| T8 | Stage II/pT4N0M0 |

| T9 | Stage II/pT3N0M0 |

| T10 | Stage II/pT3N0M0 |

| T11 | Stage IV/pT3N2M1 |

| T12 | Stage IV |

| T13 | Stage III/pT3N1M0 |

| T14 | Stage IV |

| T15 | Stage III/pT3N1M0 |

| T16 | Stage III/pT3N2M0 |

| T17 | Stage IV/pT4N1M1 |

| T18 | Stage III/pT3N1M0 |

| T19 | Stage IV |

| T20 | Stage III/pT4N1M0 |

| T21 | Stage III |

| T22 | Stage II |

| T23 | Stage III/pT3N1M0 |

| T24 | Stage II/pT3-4N0M0 |

| T25 | Stage IV/pT4N1M1 |

| T26 | Stage II/pT3N0M0 |

| T27 | Stage III/pT3N1M0 |

The subjects were admitted to the University Malaya Medical Centre, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, and underwent curative surgical resection between 2010 and 2011. None had received preoperative chemoradiotherapy. The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee Board of University Malaya Medical Centre (Ref. No. 654.1), and written informed consent was obtained from all study patients. The tumouric specimens were excised from the primary colorectal tumours, while the non-cancerous tissue specimens were obtained from distally located macroscopically normal colonic mucosa. Both colorectal tumour and paired non-cancerous tissue specimens were immersed in RNAlater RNA Stabilisation Reagent (Qiagen) immediately after excision and stored at −80°C.

Total RNA extraction

Total RNA was extracted from homogenised colonic tissues with the RNeasy Plus Mini Kit (Qiagen) according to manufacturer's instructions. Subsequently, the RNA yield and integrity were ascertained via Agilent 2100 Bioanalyser in conjunction with Agilent RNA 6000 Nano Kits (Agilent Technologies). The values of RIN were then determined in order to assess the integrity of the isolated total RNA. In this study, only RNA samples with RIN values of 8.0–10.0 and rRNA ratios (28S/18S) of 1.5–2.5 were selected for successive applications.

ACP-based PCR analysis

First-strand cDNA synthesis

The synthesis of first-strand cDNA was performed according to the manufacturer's protocol for the GeneFishing DEG Premix Kit (Seegene), as follows: 3 µg of total RNA was added with 2 µL of 10 µM dT-ACP1 (5′-CTGTGAATGCTGCGACTACGATXXXXX(T)18-3′) and RNase-free water to a final volume of 9.5 µL. The mixture was then incubated at 80°C for 3 min, followed by chilling on ice for another 2 min. Subsequently, 4 µL of 5X RT buffer (Mbiotech), 5 µL of 2 mM dNTP (Fermentas), 0.5 µL of 40 U/µL RNase inhibitor (Mbiotech) and 1 µL of 200 U/µL M-MLV reverse transcriptase (Mbiotech) were added. This mixture was then incubated at 42°C for 90 min, heated at 94°C for another 2 min and chilled on ice for 2 min. Finally, 80 µl of DNase-free water was added to dilute the synthesised cDNA. The first-strand cDNA was stored under −20°C until further analysis.

ACP-based GeneFishing PCR

First, all four cDNA samples within each CRC and control group samples were pooled together in equal amounts. The characterisation of DEGs was then conducted via ACP-based PCR based on 20 arbitrary ACP primers (Cat. No. K1021) in a thermal cycler (Mastercycler Gradient, Eppendorf) according to the manufacturer's protocol (GeneFishing DEG Premix Kit, Seegene). Initially, the synthesis of second-strand cDNA was commenced in a one-cycle first-stage PCR: 94°C for 5 min, 50°C for 3 min and 72°C for 1 min. Next, the constructed second-strand cDNA was subjected to second-stage PCR with 40 cycles of a denaturing step at 94°C for 40 s, annealing step at 65°C for 40 s and extension step at 72°C for 40 s. Finally, a final extension step at 72°C for 5 min was carried out. The amplified products were then separated on 3% (w/v) agarose gels stained with ethidium bromide.

Cloning and sequencing

The identified differentially expressed bands were extracted from the agarose gel by using the PureLink Quick Gel Extraction Kit (Invitrogen). Each of these extracted DNA fragments was then individually cloned with the use of the TOPO TA Cloning Kit for Sequencing (Invitrogen). Subsequently, the plasmid containing the inserted DNA fragment was extracted from clones of interest via PureLink Quick Plasmid Miniprep Kit (Invitrogen). The isolated cloned plasmids were then sequenced with the ABI 3730xl DNA Analyser (Applied Biosystems). Finally, all the sequences obtained were analysed and matched for similarities with reference to the BLAST programme under the NCBI database.

RT-qPCR analysis

Reverse transcription

The total RNA isolated from 27 paired samples was reverse transcribed to first-strand cDNA, with the following protocol: 3 µg of total RNA was added with 2 µL of 0.5 µg/µL oligo(dT)12–18 (Invitrogen) and RNase-free water to a final volume of 9.5 µL. The reaction mixture was then incubated at 80°C for 3 min, followed by chilling on ice for another 2 min. Next, 4 µL of 5X first-strand buffer (Invitrogen), 5 µL of 2 mM dNTP (Fermentas), 0.5 µL of 40 U/µL RNaseOUT recombinant RNase inhibitor (Invitrogen) and 1 µL of 200 U/µL M-MLV reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen) were added to the mixture. Finally, the reaction mixture was incubated at 42°C for 90 min, heated at 94°C for another 2 min and chilled on ice for 2 min. The synthesised first-strand cDNA was stored under −20°C until further usage.

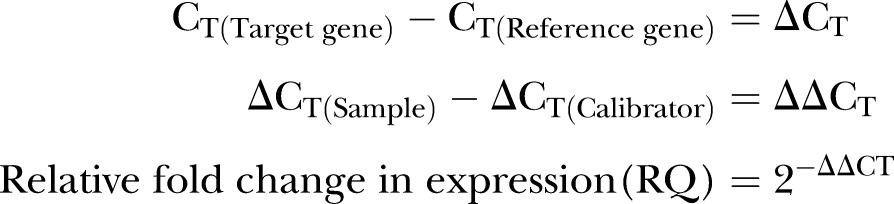

ΔΔCT analysis

The relative expression of identified DEGs in all paired colorectal tumours and control samples was determined via ΔΔCT method. The RT-qPCR was performed in a singleplex reaction containing 50 ng first-strand cDNA under universal thermal cycling conditions with the ABI 7500 Fast Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems). Both ACTB (Assay ID: Hs99999903_m1) and GAPDH (Assay ID: Hs99999905_m1) were used as reference genes and are commercially available as TaqMan Pre-designed Assays (Applied Biosystems). Prior to the analysis of gene expression, the amplification efficiency for all target and reference genes assays was measured by using the standard curve method with 2-log measurements. The amplification efficiency value of 90–110% was acceptable (Applied Biosystems). In this relative quantification method, the  values obtained represented the fold change in gene expression of the colorectal tumours, which was normalised with both reference genes, in relative to the calibrator (control sample).9

values obtained represented the fold change in gene expression of the colorectal tumours, which was normalised with both reference genes, in relative to the calibrator (control sample).9

Statistical analysis

The difference in the expression level between primary colorectal tumour and paired non-cancerous tissues was analysed by using Real-Time StatMiner software (Integromics). The distribution of the ΔCT values obtained for each DEGs within each CRC and control group were tested for normality via the Shapiro-Wilk test. Subsequently, the paired t test was performed to assess the statistical significance of the observed differential expression patterns.

Results

DEGs between colorectal tumours and non-cancerous colonic tissues

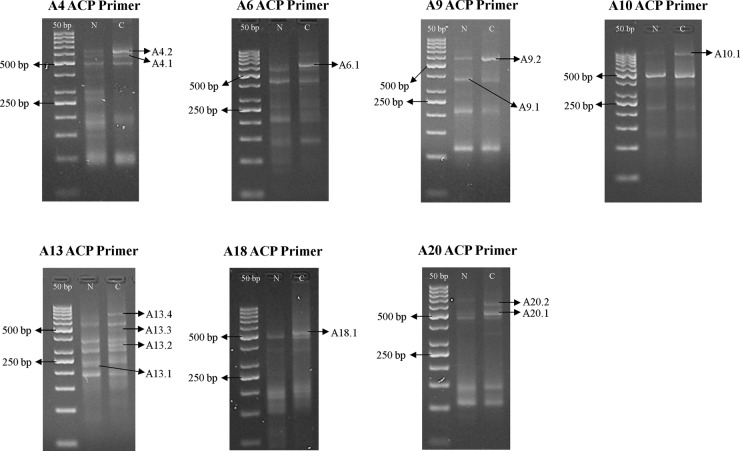

This preliminary study was conducted on paired samples pooled from four patients with CRC stages I–III. In ACP-based GeneFishing PCR, 20 sets of arbitrary ACP primers were used to randomly amplify gene products in both colorectal tumours and normal colonic samples. Upon visualisation on agarose gels, a total of 13 differentially expressed bands were observed by means of comparing bands intensity between the tumouric and non-cancerous samples, as shown in figure 1. These bands were further sequenced for gene identification, and 16 DEGs were successfully reported. Among them, 13 DEGs were overexpressed in colorectal tumours, while 3 DEGs were underexpressed, as listed in table 2.

Figure 1.

Differential banding patterns on 3% agarose gel postannealing control primer (ACP)-based PCR amplification between normal colon and colorectal tumour samples (N, normal sample; C, colorectal cancer sample).

Table 2.

Sequence similarities and identification of DEGs

| Differentially expressed band | DEG | Identity | Sequence homology (%) | Accession number | UniGene number | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overexpressed | ||||||

| A4.1 | DEG1 | Homo sapiens proteasome (prosome, macropain) 26S subunit, ATPase, 5 (PSMC5), mRNA | 502/506 (99%) | NM_002805.4 | Hs.79387 | Involves in the ATP-dependent degradation of ubiquitinated proteins |

| DEG2 | H. sapiens ubiquinol-cytochrome c reductase hinge protein (UQCRH), mRNA | 514/521 (98%) | NM_006004.2 | Hs.481571 | A component of the ubiquinol-cytochrome c reductase complex (complex III or cytochrome b-c1 complex, which is part of the mitochondrial respiratory chain | |

| A4.2 | DEG3 | H. sapiens ribosomal protein S23 (RPS23), mRNA | 551/551 (100%) | NM_001025.4 | Hs.527193 | A component of the 40S subunit of human ribosomes |

| A6.1 | DEG4 | H. sapiens ribosomal protein L10 (RPL10), transcript variant 1, mRNA | 554/557 (99%) | NM_006013.3 | Hs.534404 | A component of the 60S subunit of human ribosomes |

| A9.2 | DEG6 | H. sapiens actin related protein 2/3 complex, subunit 2, 34 kDa (ARPC2), transcript variant 2, mRNA | 473/473 (100%) | NM_005731.2 | Hs.529303 | Involves in the regulation of actin polymerisation as an actin-binding component of the Arp2/3 complex, and mediates the formation of branched actin networks together with an activating nucleation-promoting factor |

| DEG7 | H. sapiens TIMP metallopeptidase inhibitor 1 (TIMP1), mRNA | 503/511 (98%) | NM_003254.2 | Hs.522632 | Irreversibly inactivates the metalloproteinase by binding to their catalytic zinc cofactor | |

| A10.1 | DEG8 | H. sapiens ATP synthase, H+ transporting, mitochondrial F1 complex, beta polypeptide (ATP5B), nuclear gene encoding mitochondrial protein, mRNA | 917/919 (99%) | NM_001686.3 | Hs.406510 | A subunit of mitochondrial ATP synthase that catalyses the synthesis of ATP by utilising an electrochemical gradient of protons across the inner membrane during oxidative phosphorylation |

| A13.2 | DEG11 | H. sapiens chromosome 11 open reading frame 10 (C11orf10), mRNA | 273/273 (100%) | NM_014206.3 | Hs.437779 | Unknown |

| A13.3 | DEG12 | H. sapiens mitochondrial ribosomal protein L24 (MRPL24), nuclear gene encoding mitochondrial protein, transcript variant 2, mRNA | 408/411 (99%) | NM_024540.3 | Hs.418233 | Involves in protein synthesis within the mitochondrion |

| A13.4 | DEG13 | H. sapiens similar to OK/SW-CL.16 (LOC100288418) | 635/644 (98%) | XM_002342023.1 | – | Unknown |

| A18.1 | DEG14 | H. sapiens family with sequence similarity 96, member B (FAM96B), transcript variant 2, transcribed RNA | 486/487 (99%) | NR_024525.1 | Hs.9825 | Involves in chromosome segregation as part of the mitotic spindle-associated MMXD complex |

| A20.1 | DEG15 | H. sapiens ribosomal protein L35 (RPL35), mRNA | 440/446 (99%) | NM_007209.3 | Hs.182825 | A component of the 60S subunit of human ribosomes |

| A20.2 | DEG16 | H. sapiens chromosome 6 open reading frame173 (C6orf173), mRNA | 551/554 (99%) | NM_001012507.2 | Hs.486401 | May be required for proper chromosome segregation during mitosis and involved with CENPT in the establishment of centromere chromatin structure |

| Underexpressed | ||||||

| A9.1 | DEG5 | H. sapiens ribosomal protein L37 (RPL37), mRNA | 284/284 (100%) | NM_000997.4 | Hs.731513 | A component of the 60S subunit of human ribosomes, and can bind to the 23S rRNA |

| A13.1 | DEG9 | H. sapiens solute carrier family 25 (mitochondrial carrier; citrate transporter), member 1 (SLC25A1), nuclear gene encoding mitochondrial protein, mRNA | 165/165 (100%) | NM_005984.2 | Hs.111024 | A mitochondrial tricarboxylate transporter which is responsible for the movement of citrate across the mitochondrial inner membrane |

| DEG10 | H. sapiens similar to cytochrome c oxidase subunit II (LOC100288578), miscRNA | 141/146 (97%) | XR_078216.1 | – | Unknown | |

DEG, differentially expressed gene.

Differential ability of the identified DEGs on early and advanced colorectal neoplasia

Following the identification of DEGs, the gene sequences obtained were then used to design primers and TaqMan probes for RT-qPCR analysis by Applied Biosystems, as listed in table 3. In an attempt to assess the differential ability of identified DEGs on early and advanced colorectal adenocarcinomas, the recruited paired samples were further stratified into two groups according to the cancer stage. Among them, 13 patients with stages I and II were grouped as early stage CRC, while the advanced stage CRC group comprised 14 patients with stages III and IV.

Table 3.

Primers and TaqMan probes for relative quantification with Comparative CT method.

| DEG | Primers sequence |

TaqMan probe sequence | |

|---|---|---|---|

| DEG1 | Forward: Reverse: |

5′-GGGCGTGTGCACAGAAG-3′ 5′-AAGTCCTCCTGAGTGACATGGA-3′ |

5′-CTCGCAGGGCATACAT-3′ |

| DEG2 | Forward: Reverse: |

5′-GATGCTTACCGAATCCGGAGATC-3′ 5′-GCATTGCTCTCTCACTGTTGTTAG-3′ |

5′-CCTCTTCCTCTTCCTCCTCC-3′ |

| DEG3 | Forward: Reverse: |

5′-CAACCGTCATTGGGTACAAAGG-3′ 5′-TGTAAGGGTCCAGCTGATCAAGA-3′ |

5′-ATGGCAAGAAAATCAC-3′ |

| DEG4 | Forward: Reverse: |

5′-CGGCCAGGAAACTTGAACTTG-3′ 5′-CCGAGCTGCAGAACAAGGA-3′ |

5′-CAGGGCCTCAATCACA-3′ |

| DEG5 | Forward: Reverse: |

5′-CTGGTCGAATGAGGCACCTAAAA-3′ 5′-TGGGTTTAGGTGTTGTTCCTTCAC-3′ |

5′-CATGCCTGAATCTGC-3′ |

| DEG6 | Forward: Reverse: |

5′-AGATTAGCGGGATGAAAACGTCTT-3′ 5′-CGCCCAGATGCCGAGAAAA-3′ |

5′-CCCCGTGATTGTTTTC-3′ |

| DEG7 | Forward: Reverse: |

5′-GGTAGTGATGTGCAAGAGTCCAT-3′ 5′-CCGCAGCGAGGAGTTTCT-3′ |

5′-CATTGCTGGAAAACTG-3′ |

| DEG8 | Forward: Reverse: |

5′-GAAGGAGACCATCAAAGGATTCCA-3′ 5′-GAAGGCCTGTTCTGGGAGATG-3′ |

5′-ATTCACCTGCCAAAATC-3′ |

| DEG9 | Forward: Reverse: |

5′-GGCAGGGTGGTCCTGAGA-3′ 5′-CCGCCATTGGCCTTAACTG-3′ |

5′-CCTCTCTCCGCCCCGGACA-3′ |

| DEG11 | Forward: Reverse: |

5′-CAGGTTTCAGTGAAGCCATCTG-3′ 5′-GGGTTGGCATCTACGTGTGA-3′ |

5′-CACCCAAGGGTAACAAC-3′ |

| DEG12 | Forward: Reverse: |

5′-CCAGGTCAAACTTGTGGATCCT-3′ 5′-GCTTCAGTAAATCTCCACTCGATCT-3′ |

5′-ATGGACAGGAAACCCAC-3′ |

| DEG14 | Forward: Reverse: |

5′-CCCGCTCCTTATCTGCAAGTT-3′ 5′-TCAAGATGGACGTGCACATTACTC-3′ |

5′-CATGCAGTGAACAAGC-3′ |

| DEG15 | Forward: Reverse: |

5′-CGGCCTCCAAGCTCTCT-3′ 5′-TGAGAACACGGGCAATGGATTT-3′ |

5′-CCGGACGACTCGGATCT-3′ |

| DEG16 | Forward: Reverse: |

5′-GGACTCTTCTGCTAATCGATGAACA-3′ 5′-GCCTCAACTTCGTCTGGAGAAAA-3′ |

5′-CAGATGGACCAATAAGTCA-3′ |

DEG, differentially expressed gene.

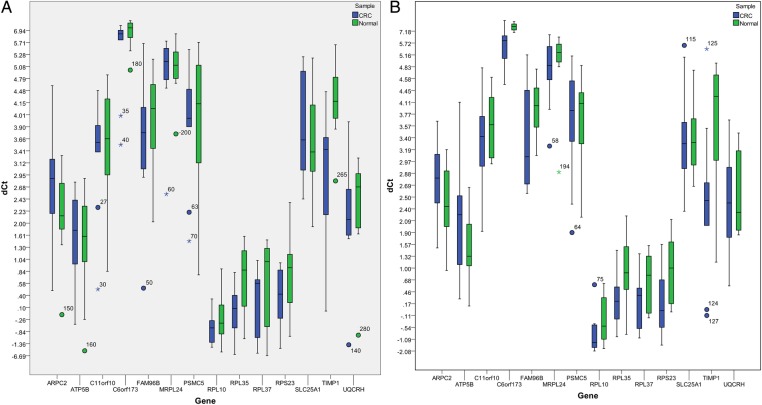

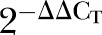

The analysis of RT-qPCR results was performed via Real-Time StatMiner software by importing the raw Ct data. The within-group correlation of these ΔCT values was then determined by calculating the median absolute deviation for all the samples within the same experimental group. The biological samples that do not correlate well with other samples in the same group, were detected as group outliers and excluded from subsequent analysis. Both ACTB and GAPDH were used for normalisation in computing the ΔCT (figure 2) and  values by using the following formulas (table 4):

values by using the following formulas (table 4):

|

Figure 2.

Box plots showing ΔCT values of all colorectal tumours and normal colonic tissues in each early (A) and advanced (B) stage colorectal cancer (CRC) group.

Table 4.

ΔCT mean, ΔΔCT, 2−ΔΔCT and p values for all the differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in early and advanced stage colorectal cancer (CRC) groups

| DEG | Early stage CRC |

Advanced stage CRC |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ΔCT mean (CRC) | ΔCT mean (normal) | ΔΔCT |  |

p Value | ΔCT mean (CRC) | ΔCT mean (normal) | ΔΔCT |  |

p Value | |

| ARPC2 | 2.6854 | 2.0664 | 0.6190 | 0.6511 | 0.0282* | 2.7240 | 2.3300 | 0.3940 | 0.7610 | 0.2424 |

| ATP5B | 1.5846 | 1.2702 | 0.3144 | 0.8042 | 0.3524 | 1.9558 | 1.3838 | 0.5720 | 0.6727 | 0.1484 |

| C11orf10 | 3.2897 | 3.3639 | −0.0742 | 1.0528 | 0.8333 | 3.3281 | 3.6709 | −0.3428 | 1.2682 | 0.3710 |

| C6orf173 | 6.1083 | 7.1943 | −1.0860 | 2.1228 | 0.0905 | 5.9949 | 7.9087 | −1.9138 | 3.7680 | 0.0013* |

| FAM96B | 3.5602 | 3.8955 | −0.3353 | 1.2616 | 0.2935 | 3.5276 | 3.9920 | −0.4644 | 1.3797 | 0.2113 |

| MRPL24 | 4.9171 | 5.0839 | −0.1668 | 1.1226 | 0.3564 | 4.9728 | 5.1467 | −0.1739 | 1.1281 | 0.7001 |

| PSMC5 | 3.8232 | 3.9617 | −0.1385 | 1.1008 | 0.6812 | 3.7705 | 3.8455 | −0.0750 | 1.0534 | 0.8048 |

| RPL10 | −0.7462 | −0.4853 | −0.2609 | 1.1982 | 0.4001 | −1.1576 | −0.5196 | −0.6380 | 1.5562 | 0.0950 |

| RPL35 | −0.1926 | 0.6222 | −0.8148 | 1.7591 | 0.0024* | 0.1748 | 0.8769 | −0.7021 | 1.6269 | 0.0372* |

| RPL37 | −0.0059 | −0.1539 | 0.1480 | 0.9025 | 0.8645 | 0.2184 | 0.7143 | −0.4959 | 1.4102 | 0.1537 |

| RPS23 | 0.2176 | 0.7739 | −0.5563 | 1.4705 | 0.0310* | 0.0676 | 0.9431 | −0.8755 | 1.8346 | 0.0250* |

| SLC25A1 | 3.7514 | 3.5430 | 0.2084 | 0.8655 | 0.5721 | 3.5565 | 3.4428 | 0.1137 | 0.9242 | 0.7991 |

| TIMP1 | 2.9096 | 4.3059 | −1.3963 | 2.6323 | 0.0440* | 2.3330 | 3.8547 | −1.5217 | 2.8713 | 0.0062* |

| UQCRH | 2.0087 | 2.2216 | −0.2129 | 1.1590 | 0.4108 | 2.3375 | 2.4459 | −0.1084 | 1.0780 | 0.7808 |

*p<0.05=statistically significant.

The relative fold change in the mRNA expression level between the colorectal tumours and adjacent normal colonic mucosa was shown as the  values. The statistical significance of the observed fold change in expression was determined by paired t test for all the DEGs. A p value of less than 0.05 is considered as statistically significant (table 4).

values. The statistical significance of the observed fold change in expression was determined by paired t test for all the DEGs. A p value of less than 0.05 is considered as statistically significant (table 4).

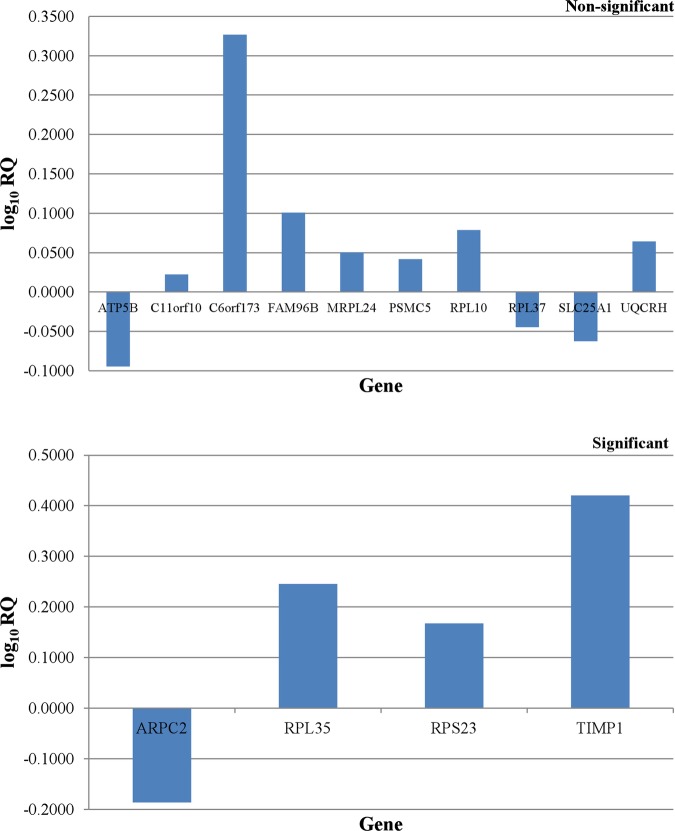

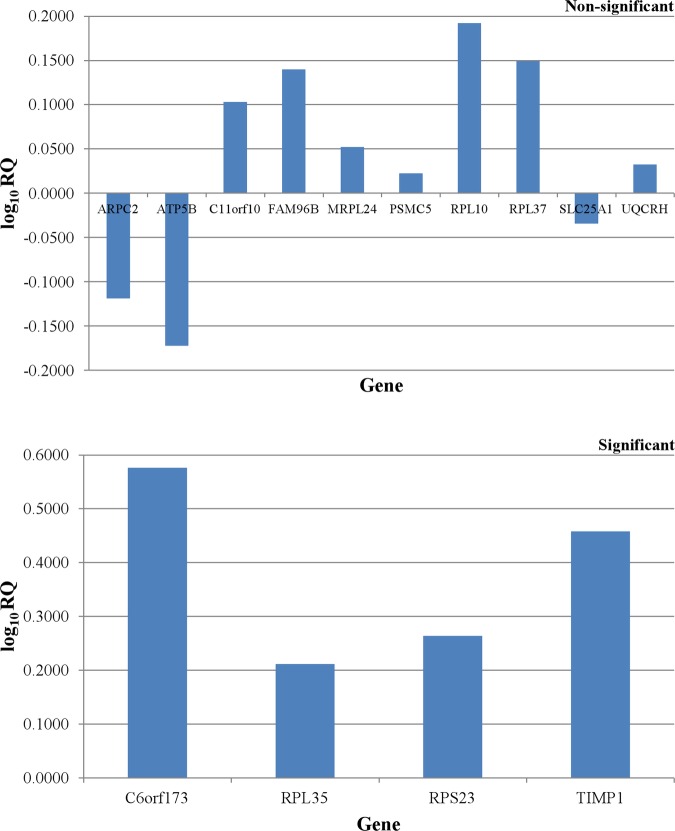

In both early and advanced stage CRC groups, the expression of 4 of 16 DEGs was reported to be significantly differed between tumouric and non-cancerous tissues. Remarkably, the combination of this panel of four genes is different among two groups. The RPL35, RPS23 and TIMP1 genes were found to be overexpressed in early and advanced colorectal neoplasms (p<0.05) (figures 3 and 4). It is interesting to note that the under-expression of ARPC2 gene (p<0.05) was only observed in early stage colorectal tumours (figure 3). However, the C6orf173 gene was found to be overexpressed (p<0.05) in advanced colorectal adenocarcinomas, but not in early stage colorectal tumours (figure 4).

Figure 3.

Differential expression patterns of all the identified differentially expressed genes in early stage colorectal cancer group.

Figure 4.

Differential expression patterns of all the identified differentially expressed genes in advanced stage colorectal cancer group.

Discussion

Our current study has revealed two distinctive four-gene signatures for both early and advanced stage colorectal adenocarcinomas. The early stage sporadic CRC was characterised by the overexpression of RPL35, RPS23 and TIMP1 genes, as well as underexpression of ARPC2 gene. However, the advanced primary colorectal tumours were reported with overexpression of C6orf173, RPL35, RPS23 and TIMP1 genes. Although the relative fold change for ARPC2, RPL35 and RPS23 genes is below 2, the individual result does not affect the analysis as gene expression patterns of all four genes in combination were proposed to distinguish between the early and advanced stage colorectal neoplasms. The potential involvement of these DEGs and their altered expression levels in CRC were further supported by previous researches.

In fact, several proto-oncogenes and tumour suppressors are previously reported to regulate the ribosome production, that is, the RB,10 TP53,11 PTEN genes,12 as well as the MYC gene family.13 It is suggested that the alterations in ribosome biogenesis might affect the translation of genes that are involved in neoplastic transformation. In addition, the additional extra-ribosomal functions of the ribosomal proteins (r-proteins) in cellular apoptosis, cellular proliferation, cellular transformation, genes transcription, mRNA translation, DNA repair and inflammation, might also trigger and support the neoplastic development.14 Hence, the overexpression of r-proteins-encoding genes observed in colorectal adenocarcinomas is not unexpected.15–17 Our current study has revealed the significant overexpression of two r-proteins that were not previously described in colorectal tumours, that is, the RPL35 and RPS23. The observed fold changes for the RPL35 and RPS23 mRNA levels were comparable between the early and advanced stage colorectal tumours in our sample cohort. This was in agreement with previous reports by Barnard et al18 and Frigerio et al,19 where the changes in the mRNA expression levels of the r-proteins were irrespective of the cancer stage. The hypothesis that the same ribosomal protein may contribute in different stages of cancer progression with their hitherto unknown extra-ribosomal roles might provide an explanation to these observations.20

However, our current study also demonstrated an over-expression of the TIMP1 gene in both early and advanced stage primary colorectal tumours. This finding is supported by Zeng et al,21 where the overexpression of TIMP1 was reported in all stages of primary colorectal tumours. Under normal physiological conditions, the proteolytic activities of MMPs are kept at bay by their natural inhibitors, the TIMPs.22 Previous studies have reported the overexpression of MMPs in early and advanced stage colorectal tumours, as well as other cancer types,23–25 which is in accordance to their biological roles. Hence, a similar scenario is expected for TIMPs and indeed, their suppressive role in tumour invasion and metastasis has been demonstrated in various cancer models.26 However, more recent studies have revealed a direct correlation between TIMP1 expression and tumour aggressiveness in cancer, including CRC.21 27 These findings, which are contradictory to its protease-inhibiting function, have suggested a possible tumour-promoting role of TIMP1 in tumorigenesis. It is postulated that the TIMP1 exhibits the abilities to inhibit tumour cell apoptosis and promote tumour angiogenesis, as well as other growth-factor-like effects.28 In our current study, the observed comparable overexpression of TIMP1 in early and advanced stage sporadic colorectal neoplasms was in line with its MMP inhibitory and MMP-independent tumour-promoting activities.

In cancer biology, the expression of mRNAs and proteins of the ARP2/3 complex is often studied due to its role in cell migration, which contributes to cancer invasion and metastasis if aberrantly regulated.29 We have detected a significant underexpression of ARPC2 in our cohort of early stage primary colorectal tumours. Surprisingly, this finding is contradictory with the role played by ARPC2 in cancer invasion and metastasis theoretically. Previously, Kaneda et al has reported the decreased expression of all the seven genes encoding the subunits of ARP2/3 complex in human gastric cancers. Among them, the Arp2, ARPC2 and ARPC3 showed the most prominent reduction in their expression levels.30 The exact mechanism underlying this observation still remains unknown, but the epigenetic alteration might potentially provide an explanation for it. For instance, promoter hypermethylation that causes gene silencing is responsible for the reduced expression of ARPC1 in human gastric cancer.31 Similarly, the epigenetic study might also offer a clue for the underexpression of ARPC2 in colorectal neoplasms.

C6orf173, which is also known as CUG2 or CENP-W, is a novel oncogene that has been found to be upregulated in many human cancer tissues. Its high expression level is profoundly reported in tumours of the ovary, liver, lung, pancreas, breast, colon, rectum and stomach. The CENP-W is a new member of the constitutive centromere-associated network, which specifically interacts with the CENP-T and plays an important role in mitosis.32 In our current study, the CENP-W is over-expressed in advanced colorectal adenocarcinomas. This finding correlates to its function in kinetochore assembly, where its aberrant expression might lead to abnormal cell division and aneuploidy in cancer.32 In our study, the overexpression of CENP-W was observed in early and advanced cohort of colorectal neoplasms but only statistically significant in the latter group. Given the fact that aneuploidy is constantly associated with a greater proportion of advanced CRC cases, the aberrant expression of CENP-W might potentially relate to a poorer prognosis of CRC.33

In conclusion, we have characterised two distinctive gene expression patterns, which comprise the ARPC2, C6orf173, RPL35, RPS23 and TIMP1 genes, for the stratification of primary colorectal adenocarcinomas among Malaysian CRC patients. It was postulated that the actin cytoskeleton might play an important role in determining the dysplastic cell morphology during the early development of CRC, while the aberration in the assembly of functional kinetochore might be crucial for the aneuploidy of the advanced stage colorectal tumours. Nevertheless, the findings of this study were considered preliminary owing to the relatively small sample size. The main reason for this is the lack of a designated Tissue Bank in our institution. Moreover, the lack of patient with CRC volunteers and our stringent criteria for patient selection have also limited the availability of suitable specimens within the short sample collection period.

However, our identified mRNA expression patterns specific for early and advanced stage colorectal tumours are still convincing with our stringent sample selection criteria, high specificity primers and probes as well as reliable statistical analysis. In future, the validation of these DEGs should be performed on a larger set of clinical samples, and extensive inter-laboratory testing of their differential abilities on each CRC stage is also desired. In addition, we should also integrate other imaging and histological information to complement our identified gene expression patterns, which then hold promises for better stratification of tumours.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: KHC, KLG, IH, HCC and ACR had the original idea for this work and gained funding in collaboration with PCL. TPL carried out the experiment. TPL, KHC, PCL, HCC and LHL were involved in the data analysis. TPL wrote the first draft of this paper and all authors subsequently assisted in redrafting and have approved the final version.

Funding: This study was supported by FS176/2007C, PS172/2008C and Research Collaborative Grant, CG041-2013 from the University of Malaya.

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: Ethics Committee Board of University of Malaya Medical Center (Ref. No. 654.1).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Greene FL, Page D, Fleming ID, et al., eds AJCC cancer staging manual. 6th edn New York: Springer, 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dukes CE. The classification of cancer of the rectum. J Pathol Bacteriol 1932;35:323–32 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Astler VB, Coller FA. The prognostic significance of direct extension of carcinoma of the colon and rectum. Ann Surg 1954;139:846–52 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Edge SB, Byrd DR, Compton CC, et al. AJCC cancer staging manual. 7th edn New York: Springer, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hu HK, Krasinskas A, Willis J. Perspectives on current tumour-node-metastasis (TNM) staging of cancers of the colon and rectum. Semin Oncol 2011;38:500–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Doyle VJ, Bateman AC. Colorectal cancer staging using TNM 7: is it time to use this new staging system? J Clin Pathol 2012;65:372–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Russo G, Zegar C, Giordano A. Advantages and limitations of microarray technology in human cancer. Oncogene 2003;22:6497–507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Puppa G, Sonzogni A, Colombari R, et al. TNM staging system of colorectal carcinoma: a critical appraisal of challenging issues. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2010;134:837–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT method. Methods 2001;25:402–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Voit R, Schafer K, Grummt I. Mechanism of repression of RNA polymerase I transcription by the retinoblastoma protein. Mol Cell Biol 1997;17:4230–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhai W, Cornai L. Repression of RNA polymerase I transcription by the tumour suppressor p53. Mol Cell Biol 2000;20:5930–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Backman S, Stambolic V, Mak T. PTEN function in mammalian cell size regulation. Curr Opin Neurobiol 2002;12:516–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Greasley PJ, Bonnard C, Amati B. Myc induces the nucleolin and BN51 genes: possible implications in ribosome biogenesis. Nucleic Acids Res 2000;28:446–53 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Montanaro L, Treré D, Derenzini M. Nucleolus, ribosomes, and cancer. Am J Pathol 2008;173:301–10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sharp MG, Adams SM, Elvin P, et al. A sequence previously identified as metastasis-related encodes an acidic ribosomal phosphoprotein, P2. Br J Cancer 1990;61:83–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chester KA, Robson L, Begent RH, et al. Identification of a human ribosomal protein mRNA with increased expression in colorectal tumours. Biochim Biophys Acta 1989;1009:297–300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pogue-Geile K, Geiser JR, Shu M, et al. Ribosomal protein genes are overexpressed in colorectal cancer: isolation of a cDNA clone encoding the human S3 ribosomal protein. Mol Cell Biol 1991;11:3842–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barnard GF, Staniunas RJ, Mori M, et al. Gastric and hepatocellular carcinomas do not overexpress the same ribosomal protein messenger RNAs as colonic carcinoma. Cancer Res 1993;53:4048–52 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Frigerio JM, Dagorn JC, Iovanna JL. Cloning, sequencing and expression of the L5, L21, L27a, L28, S5, S9, S10 and S29 human ribosomal protein mRNAs. Biochim Biophys Acta 1995;1262:64–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lai MD, Xu J. Ribosomal proteins and colorectal cancer. Curr Genomics 2007;8:43–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zeng ZS, Cohen AM, Zhang ZF, et al. Elevated tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase 1 RNA in colorectal cancer stroma correlates with lymph node and distant metastases. Clin Cancer Res 1995;1:899–906 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ennis BW, Matrisian LM. Matrix degrading metalloproteinases. J Neurooncol 1994;18:105–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Urbanski SJ, Edwards DR, Maitland A, et al. Expression of metalloproteinases and their inhibitors in primary pulmonary carcinomas. Br J Cancer 1992;66:1188–94 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Boag AH, Young ID. Immunohistochemical analysis of type IV collagenase expression in prostatic hyperplasia and adenocarcinoma. Mod Pathol 1993;6:65–8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Newell KJ, Witty JP, Rodgers WH, et al. Expression and localisation of matrix-degrading metalloproteinases during colorectal tumourigenesis. Mol Carcinogen 1994;10: 199–206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Khokha R, Waterhouse P. The role of tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-1 in specific aspects of cancer progression and reproduction. J Neurooncol 1994;18:123–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lu XQ, Levy M, Weinstein IB, et al. Immunological quantitation of levels of tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-1 in human colon cancer. Cancer Res 1991;51:6231–5 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Egeblad M, Werb Z. New functions for the matrix metalloproteinases in cancer progression. Nat Rev Cancer 2002;2:161–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yamaguchi H, Wyckoff J, Condeelis J. Cell migration in tumours. Curr Opin Cell Biol 2005;17:559–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kaneda A, Kaminishi M, Sugimura T, et al. Decreased expression of the seven ARP2/3 complex genes in human gastric cancers. Cancer Lett 2004;212:203–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kaneda A, Kaminishi M, Nakanishi Y, et al. Reduced expression of the insulin-induced protein 1 and p41 ARP2/3 complex genes in human gastric cancers. Int J Cancer 2002;100:57–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hori T, Amano M, Suzuki A, et al. CCAN makes multiple contacts with centromeric DNA to provide distinct pathways to the outer kinetochore. Cell 2008;135:1039–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chen HS, Sheen-Chen SM, Lu CC. DNA index and S-phase fraction in curative resection of colorectal adenocarcinoma: analysis of prognosis and current trends. World J Surg 2002;26:626–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.