Abstract

One opportunity to realize the diversity goals of academic health centers comes at the time of hiring new faculty. To improve the effectiveness of search committees in increasing the gender diversity of faculty hires, the authors created and implemented a training workshop for faculty search committees designed to improve the hiring process and increase the diversity of faculty hires at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. They describe the workshops, which they presented in the School of Medicine and Public Health between 2004 and 2007, and they compare the subsequent hiring of women faculty in participating and nonparticipating departments and the self-reported experience of new faculty within the hiring process. Attendance at the workshop correlates with improved hiring of women faculty and with a better hiring experience for faculty recruits, especially women. The authors articulate successful elements of workshop implementation for other medical schools seeking to increase gender diversity on their faculties.

The National Institutes of Health, the American Medical Association, and the Association of American Medical Colleges have all expressed concern about the underrepresentation of women in academic medicine—particularly in leadership positions. Despite impressive increases in the number and percentage of women who have earned MD degrees since the 1970s (9% in 1970, 25% in 1980, 36% in 1990, 43% in 2000, and 49% in 20071), women physicians continue to be underrepresented in the faculty ranks. In 2008, 40% of assistant professors, 29% of associate professors, and 17% of full professors were women.1 Rectifying this gender imbalance in the highest levels of academic medicine is a national imperative, not only to ensure that U.S. medical schools make optimal use of the talent they train2 but also to help ensure that future physicians train in institutions that reflect the composition of the population of the United States, that women medical students will have access to role models who may inspire them to consider careers in academic medicine,3–7 and that women’s health issues continue to receive attention in curricula, research, and public policy.8,9

The National Science Foundation (NSF) has noted a similar gender imbalance in the leadership of academic science and engineering. After years of attempting to increase gender diversity in U.S. academic science and engineering leadership through awards to individual women (e.g., Research Opportunities for Women, Visiting Professorships for Women, Career Advancement Awards, Faculty Awards for Women, and Professional Opportunities for Women in Research and Education), the NSF changed course in the early 21st century and chose to focus on the institutions in which academic scientists and engineers work rather than on individuals within those institutions.10 In 2001, the NSF announced the ADVANCE program with a new solicitation for proposals that would result in “institutional transformation.” The goal of the ADVANCE program is to increase the participation and advancement of women in academic science and engineering; as such, it is an effort focused primarily on transforming the policies, practices, and climates for faculty in U.S. research institutions.10,11

The University of Wisconsin–Madison (UW-Madison) received one of the first ADVANCE Institutional Transformation grants in January 2002. The ADVANCE team coprincipal investigators (M.C., J.H., J.T.S.) at UW-Madison formed a research center—WISELI: Women in Science & Engineering Leadership Institute12—to centralize all ADVANCE-related activities. WISELI focused immediately on the faculty hiring process as an essential element of success. Although multiple junctures in a scientist’s career determine whether an individual reaches the highest leadership levels (e.g., sequential promotion from assistant professor to associate professor to professor),13,14 perhaps one of the most critical junctures in the faculty career is the point of hire. The faculty hiring process of any university determines the demographic composition of its faculty for decades because a faculty career can span 20 to 40 years. Emphasizing the search and screen process and working to add more women to the faculty by reforming that process is an important place to begin in order to achieve the goal of increasing both the proportion and number of women faculty. To accomplish this goal, WISELI designed an intervention for UW-Madison faculty hiring committees that incorporated the following:

principles of adult learning, including peer teaching and active engagement in the learning process15–19;

tenets of intentional behavioral change, which state that an individual must first recognize the existence of a problem (e.g., gender bias) before committing to behaviors aimed at reducing the problem20–24; and

recommendations from organizational change research that emphasize the importance of leadership, resources, engaging employees in the change, and creating a sense of urgency.25–31

The University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health (UWSMPH) participated in this campus-wide initiative.

Needs assessment

The persistent gap between the number and percentage of women medical graduates and their representation on the faculties of U.S. medical schools demonstrates the need to address the process of hiring faculty. Additionally, in 2003, the UWSMPH fell below the national average for recruiting women faculty.32 We began to assess the need for a new hiring approach by examining existing institutional practices of recruiting and hiring new faculty. In the UWSMPH, the general practice for faculty recruitment is for the department chair to appoint search committees of approximately 4 to 10 faculty and staff members and to assign a committee chair or two cochairs. The UWSMPH dean appoints faculty and staff to serve on search committees for department heads. These search committees are responsible for conducting national searches, for recruiting and evaluating job applicants, and for selecting the final candidates who will visit campus and interview for the available position. The role search committees play in determining which candidate receives a job offer varies across departments. Search committees’ responsibilities may end with the selection of finalists; committees may rank the finalists and submit their rankings to the department chair and/or the departmental executive committee (composed of all faculty members at the associate professor level or higher); or the committee may recommend a particular finalist for hire. The departmental executive committee has final responsibility for either approving the selection made by the search committee or department chair or for actually selecting the candidate. These procedures are in accordance with UW-Madison’s policies on faculty hires.33,34

After the evaluation of existing hiring practices, we embarked on a series of discussions about the search process with administrative leaders, department chairs, senior women faculty, and human resources personnel. We also compared typical faculty search processes with those for senior academic leadership positions (e.g., assistant professor versus dean). We reviewed many documents regarding women and minorities in academia along with research from multiple disciplines on unconscious biases that might influence the hiring process.35–38 During these discussions, faculty, chairs, and administrators expressed a genuine desire to increase the gender diversity of their departments but recognized that they did not have the knowledge, skills, or experiences to actually effect this change. They acknowledged that search committees frequently served primarily as evaluating bodies and did not engage extensively in recruiting, that committee members and chairs may or may not have had previous experience on search committees, and that neither committee chairs nor members received any form of training or systematic guidance on how to recruit and evaluate faculty. Although the UW-Madison Search Handbook34 exists, most faculty and chairs have not been aware of it. This handbook provides valuable and useful information, but the information is primarily procedural in nature and does not directly address the unconscious biases and assumptions that may affect the evaluation of and behavior toward candidates.

These discussions with faculty and administration, together with the research literature, identified two primary areas of concern: (1) search committees do not actively recruit women and minorities into the pool of applicants, and (2) unconscious biases may be influencing evaluations of women and/or minority applicants. In addition, discussions with women faculty indicated that women and underrepresented minorities frequently endured negative experiences (e.g., questions about marital status or future childbearing plans) during on-campus interviews and that providing education about inappropriate questions and creating a positive interview experience was critical for hiring women and minority faculty. Finally, all parties expressed the need for providing search committee members with both basic training in good search practices and practical advice for the logistics of conducting a search.

The discussions conducted during this needs assessment confirmed that the decentralized nature of our campus and the strong tradition of faculty governance combine to form a culture at UW-Madison in which faculty generally view workshops emanating from campus administration as a nuisance. Faculty and administrative leaders, however, place high value on programs that the faculty initiate, especially when they include research and scholarship. Thus, we chose to locate the orchestration of the workshops within a research center (WISELI) rather than in the Office of the Provost or other administrative office.

WISELI sought to create a sense of urgency for institutional change— capitalizing on individuals’ motivations to be more effective members or chairs of search committees and aligning its approach to faculty development with institutional core values—by using a data-driven, evidence-based method. To accomplish all these objectives, WISELI sought and received visible support from campus leaders including an endorsement from the dean of the UWSMPH who publicly agreed that the effort to diversify faculty and improve hiring addressed an institutional need. We also consistently emphasized that these workshops were part of a research program supported by the NSF with faculty principal investigators. To increase self-efficacy among search committee participants for recruiting and evaluation tasks, the workshops integrated research-based content knowledge with practical skills that participants could immediately apply and practice in a real-world context.

Workshop Design

WISELI convened a design team of 12 members consisting of faculty and staff from across the campus to develop a workshop or workshop series that would educate faculty and staff about effective practices surrounding the hiring of faculty. The design team included WISELI codirectors who have experience in education39 and behavioral change24; WISELI staff (J.T.S., E.F., C.M.P., J.H., M.C.); and other stakeholders from across the campus such as faculty and chairs from a variety of departments (including from the UWSMPH), directors and personnel from human resources, the UWSMPH ombudsperson, and representatives from the Office of the Provost. WISELI leaders selected these members on the basis of their experience, expertise, and commitment to improving the hiring process and increasing diversity in faculty ranks. Relying on the initial needs assessment, the design team extensively discussed workshop content and structure as it developed materials. The design team met once a month over an eight-month period, with each meeting lasting approximately two hours. Several team members spent additional time outside of the meetings locating materials, talking to colleagues and experts, and preparing research summaries to inform the team’s work. The result was a first workshop piloted in 2003. As part of an ongoing development process, participants in the pilot workshop provided feedback that influenced the final materials and workshop design. Formally named “Searching for Excellence & Diversity,”40 WISELI began implementing the workshops campus-wide in 2004. WISELI advertised the workshops primarily to chairs and members of search committees but also encouraged others (department heads and departmental administrators who assist with a search) to attend as well.

Workshop Format and Content

Whereas the goal of the NSF ADVANCE program is to increase the participation and advancement of women in academic science, the goal of an academic unit is to increase diversity more broadly, including (but not limited to) gender and racial/ethnic diversity. In the Searching for Excellence & Diversity workshops, WISELI emphasizes that the concepts and practices put forth in the workshop are broadly applicable to recruiting individuals from any group that has been historically underrepresented on the faculties of academic health centers. WISELI evaluated the workshops with regard to gender, but the actual workshop content defines diversity more broadly.

The content of the workshops revolves around the “Five Essential Elements of a Successful Search.”41 The first element, Run an effective and efficient search committee, provides tips and techniques for organizing the search process, running committee meetings, and successfully utilizing the time and energy of all search committee members. Presenters stress the importance of following state laws and university policies and procedures for the search, and they introduce relevant selections from the university’s official search handbook.34 Presenters also advise committees to establish consensus about ground rules and guidelines they will rely on to conduct their search. Ground rules and guidelines should include items such as a clear understanding of committee members’ roles and responsibilities, policies on attending committee meetings, decision-making procedures, and evaluation criteria for the position.

In the second workshop element, we discuss the importance of Actively recruit[ing] an excellent and diverse pool of candidates. Before addressing recruitment, we recommend that search committee members engage in a general discussion about diversity and the benefits a diverse faculty offers to the university, the UWSMPH, the department, and the students. We provide participants with the background and language needed to discuss diversity within the search committee. We provide participants with examples of comments or opinions search committee members might share (e.g., “I would not want to compromise excellence for diversity”) and with evidence-based responses they can use (e.g., “Excellence and diversity are not mutually exclusive”). We also provide participants with research they can rely on to argue for diversity (e.g., diversity is essential for achieving excellence42–44). We then turn to small-group discussion and ask participants to share successful strategies they have used to build a large and diverse applicant pool. We supplement this discussion by providing additional tips and resources for building the pool. These resources include publications targeted toward diverse audiences and information about the following: organizations serving underrepresented groups, scholarship/ fellowship programs for members of underrepresented groups, and schools with a history of awarding degrees to members of underrepresented groups. Our advice stresses the need to actively recruit diverse applicants by making personal contact with prospective candidates, by expanding individual professional networks to include members of underrepresented groups, and by relying on these networks to recruit applicants. We raise awareness about some common myths and/or assumptions that might limit the diversity of the applicant pool, and we counteract these myths with research findings and other arguments.37 For example, one common assumption is that “there are no women/minorities in our field, or no qualified women/minorities.” We highlight that although women or minorities may be scarce in some fields, it is rarely the case that there are none. Another common assumption is that “excellent candidates need the same credentials as the person leaving the position.” We note the many examples of highly successful people who have taken nontraditional career paths, and we point specifically to the fact that several successful women in academic leadership positions did not serve as chairs before becoming deans.45

The third element, Raise awareness of unconscious assumptions and their influence on evaluation of candidates, is the most innovative piece of this workshop. In this section, we present to workshop participants research on unconscious biases and assumptions from a variety of fields including psychology, sociology, economics, linguistics, and organizational behavior. This research shows that “even the most well-meaning person unwittingly allows unconscious thoughts and feelings to influence seemingly objective decisions,”46 that both men and women share the same assumptions about gender, and that when women enter historically male-dominated arenas, these assumptions can lead both men and women to underestimate the competence and potential of women,47–49 to undervalue women’s contributions,50 to fail to recognize women’s leadership abilities, and/or to regard competent women as overly aggressive or hostile.51–53 We target our presentation of this research to implications for the hiring process. We also discuss how participants might inform the other members of their committees about this research and its implications for the review of candidates. We provide participants with a case study as a basis for discussion during the workshop and with multiple copies of a brochure entitled “Reviewing Applicants: Research on Bias and Assumptions,”54 which they can take back to their committees to help initiate discussion with their colleagues. We intend for this portion of the workshop, especially its research-based focus, to enable participants to recognize both the existence and the power of unconscious gender bias and to motivate them to commit to intentional behavioral change in the context of their own search committees.

The fourth element of the workshop, Ensure a fair and thorough review of candidates, provides concrete logistical advice for organizing the review of candidates and draws on relevant research studies to provide strategies for minimizing the influence of bias and assumptions on the evaluation of candidates. We emphasize studies with randomized controlled designs of interventions that have successfully mitigated the impact of bias. One example is a study suggesting that an inclusive decision-making strategy (i.e., deciding whom to keep in the pool) is more effective at minimizing bias than an exclusionary decision-making process (i.e., deciding whom to remove from the pool55).

The fifth element, Develop and implement an effective interview process, provides advice and suggestions for arranging campus visits and interviewing candidates. This section encourages search committee members to regard the campus visit not only as an opportunity to evaluate candidates but also as an opportunity for the candidates to evaluate the department, the UWSMPH, the university, and the community. To concentrate attention on the perspective of the candidate, participants engage in paired discussions of their own experiences interviewing for an academic position. Then, formal presentations provide practical advice for ensuring that the campus visit is a good experience for the candidate—whether or not that candidate is hired. We encourage search committees to create an environment in which the candidate can perform to the best of his/her abilities. This includes, but is not limited to, recommending that participants educate all departmental members and others who will interact with candidates about which questions are and are not appropriate to ask. We also stress the importance of personalizing the visit for each candidate by determining his or her needs and by providing opportunities for the candidate to learn about the campus and the community. We strongly recommend providing every candidate with the opportunity to meet with someone on campus who is not involved in the evaluation process but who can answer questions about local resources, services, communities, lifestyle, and culture that may be crucial to the candidate’s decision to accept a job offer.

The materials we have developed for the Searching for Excellence & Diversity workshops are flexible, and they allow us to reach search committees in any number of ways. In the UWSMPH, we implemented a one-session workshop, 2.5 hours in length, which we offer to faculty twice each semester to accommodate busy schedules. (The first two workshops offered in 2004 were 2 hours, and this was not long enough, so subsequent workshops were all 2.5 hours.) Each workshop begins with an introduction from the dean or vice dean of the UWSMPH. This allows the dean’s office to demonstrate strong support for the effort to improve the search process and diversify the faculty. To foster peer learning and answer questions of particular relevance to the UWSMPH, faculty and staff from the UWSMPH present most of the material and serve as small-group facilitators. Each small group consists of 6 to 10 participants. In addition to faculty and staff from the UWSMPH, we include WISELI personnel, the director of the campus Office of Equity and Diversity, and occasionally (depending on availability) representatives from UW-Madison’s Offices of Legal Services, the Office of the Provost, and/or the Office of Community Relations. All presenters and facilitators invite participants to consult with them throughout the search process. The workshop concludes by providing participants with “Top Ten Tips” to summarize the content of presentations and discussions (List 1).

List 1.

Searching for Excellence & Diversity: Top Ten Tips for Faculty Search Committees*

Build rapport among committee members by setting a tone of collegiality, dedication, and open-mindedness.

Run efficient meetings and empower all committee members.

Make sure committee members know what is expected of them, and establish ground rules for such items as attendance, decision making, treatment of candidates, etc.

Assign tasks and hold committee members accountable.

Air views about diversity and other controversial issues.

Identify people and places who can refer you to potential candidates.

Search broadly and inclusively; save sifting and winnowing for later.

Recruit aggressively and make personal contact with potential candidates.

Discuss research on assumptions and biases and consciously strive to minimize their influence on your evaluation of candidates. 10. Ensure that every candidate interviewed on campus—whether hired or not—is respected and treated well during his or her visit.

*Source: “Searching for Excellence & Diversity: A Guide for Faculty Search Committee Chairs.” Available at: http://wiseli.engr.wisc.edu/docs/SearchBook.pdf. Back Cover.

In the UWSMPH, WISELI offered 12 workshops between 2004 and 2007. Attendance at each workshop varied from approximately 12 to 40 participants. Tenured or tenure-track (TT) faculty from 17 of 26 departments participated in at least one workshop from 2004 through 2007. Of the approximately 385 TT faculty in UWSMPH, 35 (9%) have participated in a workshop. Thirteen of these faculty attendees were UWSMPH department chairs or section heads.

Evidence of Workshop Success

The UW-Madison institutional review board (IRB) approved the data-collection protocols that allowed WISELI to evaluate the effectiveness of the workshops on a variety of measures. The IRB approved evaluation forms and a faculty-climate survey instrument. We obtained signed consent from every workshop participant, allowing us to link workshop attendance with both individual and department-related outcomes. As part of the confidentiality agreement with the IRB, we could collect department-level data as long as we presented only data that are aggregated above the department level.

Postworkshop evaluations completed anonymously online within 72 hours of the workshops provide encouraging evidence that participants have a good experience in the workshops. WISELI staff, workshop facilitators, and presenters do not complete evaluations. Fifty-nine of 78 (76%) faculty and staff workshop participants in the UWSMPH completed postworkshop evaluations. All respondents indicated that time spent in the Searching for Excellence & Diversity workshops was well spent. Approximately 93% (n = 55) would recommend the workshop to other faculty, and the majority (n = 42; 71%) indicated that it was “very useful” (as opposed to “somewhat useful” or “not useful”). Fifty-four respondents (92%) included write-in comments, and of these about half (n = 25; 46%) indicated that “recognition of unconscious bias and assumptions” was the most valuable knowledge gained in the workshop.56

Although knowing that the postworkshop evaluations are positive is important, knowing whether the workshops are meeting their goal of diversifying new faculty hires in the UWSMPH is even more so. Because we emphasize actively increasing the number and percentage of women in the applicant pool, analyzing pool data before and after implementation of the workshops would be useful; however, we have not had access to reliable pool data at UW-Madison. Instead, we have relied on hiring data to analyze the effectiveness of the Searching for Excellence & Diversity workshops. We employed a quasi-experimental design, comparing the outcomes for departments that sent at least one TT faculty member to a workshop between 2004 and 2007 with outcomes for departments that sent no TT faculty to the workshops in that time period. We compared hiring outcomes in 2000–2004 (prior to the 2004 workshop implementation) with those in 2005–2008. We also examined whether a dose–response effect exists, such that participation by one department in more workshops would result in an improved outcome in terms of hiring women faculty to that department. We have four years of postworkshop data and five years of preworkshop data. We use five years for the preworkshop period rather than four because this allows us to include all 26 departments in the UWSMPH in our analyses. Two departments did not hire any faculty between 2001 and 2004. They would have had to be excluded from analysis if we used just the four-year window. Because we are comparing percentages and not raw numbers, the addition of one extra year to the preworkshop period does little to change the overall percentages, but it does allow us to have a larger sample size, thus increasing our statistical power. The participating departments (N = 17) had 88 total hires in the preworkshop (2000–2004) period and 75 total hires in the postworkshop (2005–2008) period. The nonparticipating departments (N = 9) had 35 hires in the 2000–2004 period and 18 hires in the 2005–2008 period. Ten UWSMPH departments participated in one workshop between 2004 and 2007, and seven departments participated in two or three workshops during that period.

In addition to examining whether participating departments hired more women faculty than they had in the past, we compared newly hired UWSMPH faculty (male and female) satisfaction with the hiring process before and after workshop implementation to determine whether satisfaction differed for faculty hired into departments that participated in the workshops compared with faculty hired into departments that did not participate. For this, we used data from the Study of Faculty Worklife at UW-Madison in 200357 and 2006.58

WISELI conducted the Study of Faculty Worklife at UW-Madison survey in 2003 (prior to workshop implementation) and in 2006. All faculty at UW-Madison received the survey instrument. The campus-wide response rate was 60% (n = 1,338) in 2003 and 56% (n = 1,230) in 2006. In the UWSMPH, 57% (n = 208) of faculty responded to the survey in 2003 and 54% (n = 208) responded in 2006. As is common in most surveys of this type,59 women in the UWSMPH responded at higher rates than men in both survey waves. Nonwhite faculty responded at lower rates than white faculty in 2006; however, whites and nonwhites responded at similar rates in 2003. Response rates for both surveys are very similar across other demographic characteristics (rank, years of service, department, etc.).

Hiring outcomes

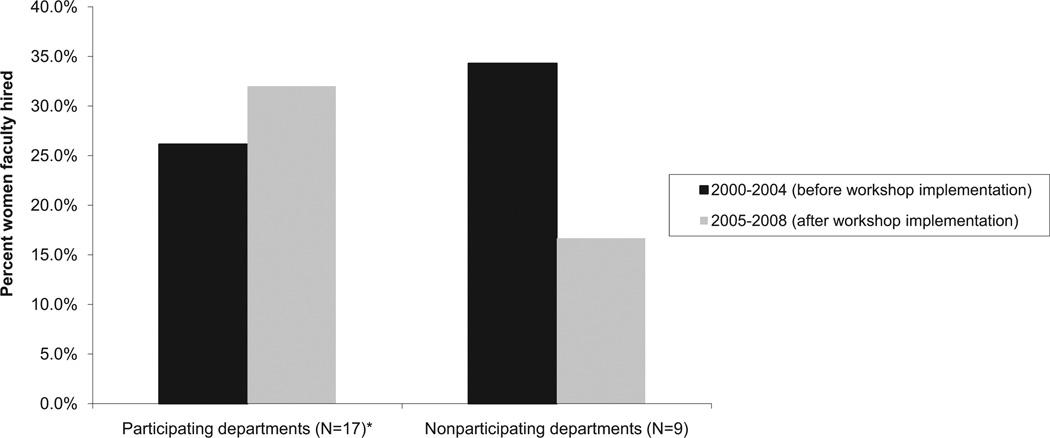

UWSMPH departments participating in at least one workshop between 2004 and 2007 experienced an increase in the percentage of women faculty hired between 2005 and 2008, compared with a decrease in the percentage of women hired into departments that did not send one faculty member to a workshop between 2004 and 2007 (P < .05, Figure 1). Because of the small number of observations (N = 26 departments), we ascertained statistical significance by bootstrapping the odds that a participating department increased the proportion of women hired in the period after training began compared with departments that did not participate (OR = 6.29; 95% confidence interval = 1.05–24.86).

Figure 1.

Percentage of new women faculty hired in the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health by any workshop attendance, 2000–2008.

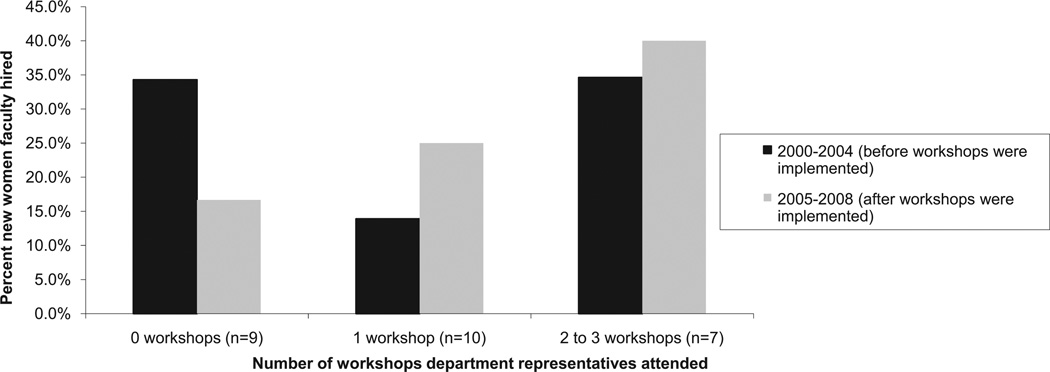

Because some departments participated in more than one workshop over the course of four years, we had the opportunity to examine whether a relationship exists between the number of workshops a department was exposed to and subsequent hiring of women faculty in that department. As shown in Figure 2, a dose–response effect does seem to exist: More women have been hired in departments participating in more workshops (though the marginal increase in proportion of women hired does not necessarily increase).

Figure 2.

Percentage of new women faculty hired in the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health by number of workshops attended, 2000–2008.

Although attendance at the WISELI Searching for Excellence & Diversity workshops is not likely to be the only explanation for the improved record of hiring women in participating departments, some evidence does seem to show a relationship between attendance and increased hiring of women faculty in the UWSMPH at UW-Madison.

Satisfaction of new faculty with the hiring process

We examined the percentage of new faculty who “agree strongly” to the following three survey items in the Study of Faculty Worklife at UW-Madison survey:

“I was satisfied with the hiring process overall.”

“Faculty in the department made an effort to meet me.”

“My interactions with the search committee were positive.”

Table 1 shows the responses of new UWSMPH faculty in 2003 (hired between 2000 and 2002, prior to the implementation of the workshops) and new UWSMPH faculty in 2006 (hired between 2003 and 2005, after the implementation of the workshops). This analysis relies on only 2004 workshop attendance because workshop attendance in 2005 or 2006 could not have affected the new hires that came in those years. We have included only UWSMPH new faculty hires in these analyses; applicants who are not hired are not asked about their experience with the hiring process in the UWSMPH.

Table 1.

Satisfaction of New* University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health Faculty With the Hiring Process: Data From the 2003 and 2006 Study of Faculty Worklife at the University of Wisconsin–Madison

| Measure | Year | New* women faculty | New* men faculty | All new* faculty | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participating departments‡ |

Nonparticipating departments‡ |

Participating departments‡ |

Nonparticipating departments‡ |

Participating departments‡ |

Nonparticipating departments‡ |

||

| Sample size | 2003 | 5 | 5 | 11 | 16 | 16 | 21 |

| 2006 | 4 | 6 | 10 | 12 | 14 | 18 | |

| % Strongly agree: I was satisfied with the hiring process overall |

2003 | 60.0 | 80.0 | 54.6 | 81.3† | 56.3 | 81.0† |

| 2006 | 100.0 | 66.7 | 60.0 | 41.7† | 71.4 | 50.0† | |

| % Strongly agree: Faculty in the department made an effort to meet me |

2003 | 75.0 | 80.0 | 63.6 | 75.0 | 66.7 | 76.2 |

| 2006 | 100.0 | 60.0 | 60.0 | 58.3 | 71.4 | 58.8 | |

| % Strongly agree: My interactions with the search committee were positive |

2003 | 50.0 | 100.0 | 62.5 | 75.0 | 60.0 | 81.0 |

| 2006 | 100.0 | 80.0 | 55.6 | 75.0 | 69.2 | 76.5 | |

For 2003, “new” faculty are those hired between 2000 and 2002; for 2006, “new” faculty are those hired between 2003 and 2005

Bold indicates significant t test at P< .05 level

Workshops were not yet offered in 2003. “Participating departments” indicates those departments that participated in the workshops offered in 2004. Nonparticipating departments did not attend a workshop in 2004. Workshop attendance in 2005 or 2006 could not have influenced faculty hired between 2003 and 2005.

New TT faculty (hired between 2003 and 2005) in departments with TT faculty who participated in the hiring workshops were more satisfied with the hiring process overall (nonsignificant; 56% were satisfied with the hiring process in 2003 compared with 71% in 2006), whereas new faculty (hired between 2003 and 2005) in those departments without TT faculty participants actually showed significantly less satisfaction with the hiring process compared with their peers hired in 2000–2002 (81% were satisfied in 2003 compared with 50% in 2006; P < .05). Interactions with the search committee showed a positive increase for women faculty in participating departments, but men in any department showed a decrease in their strong agreement that interactions with the search committee were positive. New faculty in participating departments were slightly more likely to agree strongly that faculty in their departments made an effort to meet them, compared with new faculty in nonparticipating departments. Women in participating departments were much more positive in 2006 than were other groups (both all men, and women in nonparticipating departments). In general, we conclude that participation in the Searching for Excellence & Diversity workshops correlates with a more positive search process experience for women and showed no change for men. However, in departments that did not participate, newly hired men reported significantly less overall satisfaction with the process from 2003 to 2006.

Elements of Workshop Success

We attribute the successes of the Searching for Excellence & Diversity workshops to three main features of the workshop curriculum. The first is the use of peers to lead and facilitate the workshops.60,61 When we present these workshops, we rely on faculty leadership both for the short presentations and the facilitation of the small-group discussions that occur in the workshops.62 The second reason these workshops have been successful in the UWSMPH is the use of active learning techniques in their implementation.39,63 Educational research shows that the most effective way for a person to learn a new concept is to discover it for him- or herself, especially if the new concept (e.g., “We all have biases and assumptions that may affect evaluation of candidates”) is in direct conflict with a deeply held belief (e.g., “I am a fair person who evaluates each person on his/her merit alone”).64 We use as little lecture/presentation as possible in our workshops, relying instead on small- and large-group discussion and case studies to make our points. The real learning takes place through the active discussions with other respected faculty colleagues around the table; the presentations serve only to get the conversation started. In this way, we do not present ourselves as the “experts” on hiring; instead, we regard the people seated around the room as the real experts, and we encourage them to all learn from each other.

The third reason that the workshops have been successful is our employment of peer-reviewed research on unconscious biases and assumptions and our very specific targeting of the implications of this literature for the search process. Our use of the literature to establish the pervasiveness of biases and assumptions, coupled with the connections we draw to the evaluation of candidates in the academic hiring process, helps to convince many faculty that these issues are relevant for all search committee members. Even those faculty who are aware of the research on biases and assumptions have often not taken the step to apply the research findings directly to their own work in evaluating candidates in the hiring process. Most faculty we have worked with are genuinely grateful for the opportunity to learn about their own unconscious biases so that they might work to lessen their impact, because most faculty want to be fair in their reviews. They find the specific tips and advice we give, based on the research literature, to be very helpful—especially the concise summary we provide to them in the form of our “Reviewing Applicants”54 brochure.

In Sum

Institutional transformation requires a multilayered approach, and the workshops for hiring committees are only one initiative created by WISELI to increase the gender diversity of faculty in the sciences and engineering at UW-Madison. We recognize the vital importance of retaining newly hired diverse faculty. As part of our efforts to foster retention, WISELI collaborates with UW-Madison’s Women Faculty Mentoring Program,65 offers a small-grants program to promote networking among women faculty and increase the representation of women among invited speakers for department colloquia and seminars,66 offers a workshop entitled “Enhancing Department Climate” for department chairs,67 offers workshops to new PIs,68 and administers an award-winning grant program to help faculty maintain their research programs when adverse life events affect productivity.69

The leadership of the UWSMPH has been pleased with the faculty’s reception of the Searching for Excellence & Diversity workshops, as well as with the results. The period of funding from the original ADVANCE grant has ended, but the UWSMPH and the Office of the Provost have committed resources to sustain the workshops in order to continue building a more diverse faculty. In 2007 and 2008, we trained even more faculty than we had in the past as new schools and colleges have asked us to present the workshops in their colleges, and as department chairs have requested workshops for all the faculty in their departments. We continue to monitor the diversity of hires across both the UWSMPH and the university as a whole.

Importantly, the results we present are correlations and are not necessarily causal as we did not employ an experimental design. Participation in the Searching for Excellence & Diversity workshops is voluntary. Likely, those faculty who have an interest in issues of diversity and who are already committed to increasing the diversity of academic medicine are more likely to attend the workshops and more eager to implement any process changes suggested in the workshop. However, temporal correlation between implementation of workshops and hiring outcomes, the presence of a dose–response effect, and the greater satisfaction of new hires in participating departments all provide evidence of a positive impact on the desired outcome—that is, a more diverse faculty in academic medicine.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments: The authors wish to thank Deveny Benting, Jessica Winchell, Luis Pin˜ero, Rosa Garner, Elizabeth Bolt, Paul DeLuca, and Robert Golden for their role in making the Searching for Excellence & Diversity workshops in the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health a success. They would like to thank Abhik Bhattacharya for statistical assistance.

Funding/Support: This research was funded with support from the National Science Foundation (NSF #0123666 and #0619979).

Footnotes

Other disclosures: Dr. Carnes is a part-time physician at the William S. Middleton Memorial Veterans Hospital. This is GRECC Manuscript #2010-06.

Disclaimer: Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation.

Previous presentations: The authors have frequently presented the content of their workshops, and they have presented data for the campus as a whole; however, they have not previously presented the data for just the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health, as they have done in this article.

Contributor Information

Jennifer T. Sheridan, executive and research director, WISELI: Women in Science & Engineering Leadership Institute, University of Wisconsin–Madison, Madison, Wisconsin.

Eve Fine, researcher and curriculum developer, WISELI: Women in Science & Engineering Leadership Institute, University of Wisconsin–Madison, Madison, Wisconsin.

Christine Maidl Pribbenow, evaluation director, WISELI: Women in Science & Engineering Leadership Institute, and associate scientist, Wisconsin Center for Education Research, University of Wisconsin–Madison, Madison, Wisconsin.

Jo Handelsman, Howard Hughes Medical Institute professor of molecular, cellular, and developmental biology, Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut, and past codirector, WISELI: Women in Science & Engineering Leadership Institute, University of Wisconsin–Madison, Madison, Wisconsin.

Molly Carnes, professor of medicine, psychiatry, and industrial & systems engineering, codirector, WISELI: Women in Science & Engineering Leadership Institute, director, Center for Women’s Health Research, University of Wisconsin–Madison, and director, Women Veterans Health Program, William S. Middleton Memorial Veterans Hospital, Madison, Wisconsin.

References

- 1.Association of American Medical Colleges. [Accessed February 21, 2010];Women in U.S. academic medicine statistics and medical school benchmarking. 2007– 2008 Available at: http://www.aamc.org/members/gwims/statistics/stats08/start.htm.

- 2.National Academy of Sciences; National Academy of Engineering; Institute of Medicine. Beyond Bias and Barriers: Fulfilling the Potential of Women in Academic Science and Engineering. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2007. Committee on Maximizing the Potential of Women in Academic Science and Engineering. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bickel J, Wara D, Atkinson BF, et al. Increasing women’s leadership in academic medicine: Report of the AAMC Project Implementation Committee. Acad Med. 2002;77:1043–1061. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200210000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sambunjak D, Straus SE, Marusic´ A. Mentoring in academic medicine: A systematic review. JAMA. 2006;296:1103–1115. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.9.1103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dannels S, McLaughlin J, Gleason KA, McDade SA, Richman R, Morahan PS. Medical school deans’ perceptions of organizational climate: Useful indicators for advancement of women faculty and evaluation of a leadership program’s impact. Acad Med. 2009;84:67–79. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181906d37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carnes M. Just this side of the glass ceiling. J Womens Health. 1996;5:283–286. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carnes M. Balancing family and career: Advice from the trenches. Ann Intern Med. 1996;125:618–620. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-125-7-199610010-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smedley BD, Butler AS, Bristow LR, editors. In Our Nation’s Compelling Interest: Ensuring Diversity in the Health Care Workforce. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2004. Institute of Medicine, Board on Health Sciences Policy, Committee on Institutional and Policy-Level Strategies for Increasing the Diversity of the U.S. Health Care Workforce. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carnes M, Morrissey C, Geller SE. Women’s health and women’s leadership in academic medicine: Hitting the same glass ceiling? J Womens Health. 2008;17:1453–1462. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2007.0688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rosser SV. The Science Glass Ceiling: Academic Women Scientists and the Struggle to Succeed. New York, NY: Routledge; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 11.National Science Foundation. [Accessed February 21, 2010];ADVANCE: Increasing the Participation and Advancement of Women in Academic Science and Engineering Careers. Available at: http://www.nsf.gov/pubs/2001/nsf0169/nsf0169.htm.

- 12.WISELI: Women in Science & Engineering Leadership Institute Web site. [Accessed February 21, 2010]; Available at: http://wiseli.engr.wisc.edu.

- 13.Yedidia MJ, Bickel J. Why aren’t there more women leaders in academic medicine? The views of clinical department chairs. Acad Med. 2001;76:453–465. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200105000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tesch BJ, Wood HM, Helwig AL, Nattinger AB. Promotion of women physicians in academic medicine: Glass ceiling or sticky floor? JAMA. 1995;273:1022–1025. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Knox AB. Helping Adults Learn. San Francisco, Calif: Jossey-Bass; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kaufman DM. ABC of learning and teaching in medicine: Applying educational theory in practice. BMJ. 2003;326:213–216. doi: 10.1136/bmj.326.7382.213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Howell WS. The Empathic Communicator. Belmont, Calif: Wadsworth Publishing Company; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boonyasai RT, Windish DM, Chakraborti C, Feldman LS, Rubin HR, Bass EB. Effectiveness of teaching quality improvement to clinicians: A systematic review. JAMA. 2007;298:1023–1037. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.9.1023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Knowles MS. The Adult Learner: A Neglected Species. 2nd ed. Houston, Tex: Gulf Publishing; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bandura A. Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol Rev. 1977;84:191–215. doi: 10.1037//0033-295x.84.2.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Prochaska JO, Velicer WF. The transtheoretical model of health behavior change. Am J Health Promot. 1997;12:38–48. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-12.1.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Prochaska JO, DiClemente CC. Stages of change in the modification of problem behaviors. Progr Behav Modif. 1992;28:183–218. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Janis IL, Mann L. Decision Making: A Psychological Analysis of Conflict, Choice, and Commitment. New York, NY: Free Press; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Carnes M, Handelsman J, Sheridan J. Diversity in academic medicine: The stages of change model. J Womens Health. 2005;14:471–475. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2005.14.471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nonaka I. A dynamic theory of organizational knowledge creation. Organ Sci. 1994;5:14–37. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rogers EM. Diffusion of Innovations. New York, NY: The Free Press; 1962. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Simpson DD. A conceptual framework for transferring research to practice. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2002;22:171–182. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(02)00231-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Havelock RG. Planning for Innovation Through Dissemination and Utilization of Knowledge. Ann Arbor, Mich: Center for Research on Utilization of Scientific Knowledge, Institute for Social Research, The University of Michigan; 1973. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kotter JP. Leading Change. Boston, Mass: Harvard Business School Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lindquist J. Political linkage: The academic-innovation process. J Higher Educ. 1974;45:323–343. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Simpson DD, Flynn PM. Moving innovations into treatment: A stage-based approach to program change. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2007;33:111–120. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2006.12.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Association of American Medical Colleges. [Accessed February 21, 2010];Women in U.S. Academic Medicine Statistics and Medical School Benchmarking. 2003– 2004 Available at: http://www.aamc.org/members/gwims/statistics/stats04/start.htm.

- 33.University of Wisconsin–Madison. Departmental faculties. [Accessed February 21, 2010];University of Wisconsin–Madison Faculty Policies and Procedures. Available at: http://www.secfac.wisc.edu/governance/FPP/Chapter_5.htm.

- 34.University of Wisconsin–Madison. [Accessed February 21, 2010];UW-Madison Search Handbook. Available at: http://www.ohr.wisc.edu/polproced/srchbk/sbkmain.html.

- 35.Knowles MF, Harleston BW. Achieving Diversity in the Professoriate: Challenges and Opportunities. Washington, DC: American Council on Education; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Turner CSV. Diversifying the Faculty: A Guidebook for Search Committees. Washington, DC: Association of American Colleges and Universities; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Smith DG. Achieving Faculty Diversity: Debunking the Myths. Washington, DC: Association of American Colleges and Universities; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Aguirre A., Jr Women and minority faculty in the academic workplace: Recruitment, retention, and academic culture. ASHE-ERIC Higher Educ Rep. 2000;27:1–141. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Handelsman J, Ebert-May D, Beichner R, et al. Education: Scientific teaching. Science. 2004;304:521–522. doi: 10.1126/science.1096022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.WISELI. [Accessed February 21, 2010];Searching for Excellence & Diversity: Workshops for Search Committees. Available at: http://wiseli.engr.wisc.edu/hiring.php.

- 41.WISELI. [Accessed February 21, 2010];Searching for Excellence & Diversity: A Guide for Search Committee Chairs. Available at: http://wiseli.engr.wisc.edu/docs/SearchBook.pdf.

- 42.Fields DL, Blum TC. Employee satisfaction in work groups with different gender composition. J Organ Behav. 1997;18:181–196. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Reagans R, Zuckerman EW. Networks, diversity, and productivity: The social capital of corporate R&D teams. Organization Sci. 2001;12:502–517. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sommers SR. On racial diversity and group decision making: Identifying multiple effects of racial composition on jury deliberations. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2006;90:597–612. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.90.4.597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Andrews NC. Climbing through medicine’s glass ceiling. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:1887–1889. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp078198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Banaji MR, Bazerman MH, Chugh D. How (un)ethical are you? Harv Bus Rev. 2003;81:56–64. 125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Trix F, Psenka C. Exploring the color of glass: Letters of recommendation for female and male medical faculty. Discourse Soc. 2003;14:191–220. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Steinpreis R, Anders KA, Ritzke D. The impact of gender on the review of the curricula vitae of job applicants and tenure candidates: A national empirical study. Sex Roles. 1999;41:509–528. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Biernat M, Fuegen K. Shifting standards and the evaluation of competence: Complexity in gender-based judgment and decision making. J Soc Issues. 2001;57:707–724. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wenneras C, Wold A. Nepotism and sexism in peer-review. Nature. 1997;387:341–343. doi: 10.1038/387341a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Eagly AH, Karau SJ. Role congruity theory of prejudice toward female leaders. Psychol Rev. 2002;109:573–598. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.109.3.573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ridgeway CL. Gender, status, and leadership. J Soc Issues. 2002;57:637–655. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Heilman ME, Wallen AS, Fuchs D, Tamkins MM. Penalties for success: Reactions to women who succeed at male gender-typed tasks. J Appl Psychol. 2004;89:416–427. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.89.3.416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.WISELI. [Accessed February 21, 2010];Reviewing Applicants: Research on Bias and Assumptions. Available at: http://wiseli.engr.wisc.edu/docs/BiasBrochure_2ndEd.pdf.

- 55.Hugenberg K, Bogenhausen GV, McLain M. Framing discrimination: Effects of inclusion versus exclusion mind-sets on stereotypic judgments. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2006;91:1020–1031. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.91.6.1020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Winchell JK, Pribbenow CM. [Accessed February 21, 2010];WISELI’s Workshops for Search Committee Chairs: Evaluation Report. Available at: http://wiseli.engr.wisc.edu/docs/EvalReport_hiring_ 2006.pdf.

- 57.WISELI. [Accessed February 21, 2010];Results From the 2003 Study of Faculty Worklife at UW-Madison. Available at: http://wiseli.engr.wisc.edu/docs/Report_Wave1_2003.pdf.

- 58.WISELI. [Accessed February 21, 2010];Results From the 2006 Study of Faculty Worklife at UW-Madison. Available at: http://wiseli.engr.wisc.edu/docs/Report_Wave2_2006.pdf.

- 59.Groves RM, Couper MP. Nonresponse in Household Interview Surveys. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Fagen AP, Crouch CH, Mazur E. Peer instruction: Results from a range of classrooms. Physics Teacher. 2002;40:206–209. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mazur E. Peer Instruction: A User’s Manual. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Springer L, Stanne ME, Donovan SS. Effects of small-group learning on undergraduates in science, mathematics, engineering, and technology: A meta-analysis. Rev Educ Res. 1999;69:21–51. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Johnson DW, Johnson RT, Scott L. The effects of cooperative and individualized instruction on student attitudes and achievement. J Soc Psychol. 1978;104:207–216. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ausubel D. The Acquisition and Retention of Knowledge: A Cognitive View. Boston, Mass: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 65.University of Wisconsin–Madison. [Accessed February 21, 2010];Women Faculty Mentoring Program at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. Available at: http://www.provost.wisc.edu/women/mentor.html.

- 66.WISELI. [Accessed February 21, 2010];Celebrating Women in Science & Engineering Grant Program. Available at: http://wiseli.engr.wisc.edu/celebrating.php.

- 67.WISELI. [Accessed February 21, 2010];Enhancing Department Climate: A Chair’s Role: A Workshop Series for Department Chairs. Available at: http://wiseli.engr.wisc.edu/climate.php.

- 68.WISELI. [Accessed February 21, 2010];Running a Great Lab: Workshops for Principal Investigators. Available at: http://wiseli.engr.wisc.edu/pi.php.

- 69.WISELI. [Accessed February 21, 2010];Vilas Life Cycle Professorships. Available at: http://wiseli.engr.wisc.edu/vilas.php.