Abstract

Previous studies have found adverse effects of maternal employment on child obesity for higher educated mothers. Using a quasi-structural model, we find additionally a lower risk of obesity for children of less educated mothers with increased time in non-parental childcare.

Keywords: Child Obesity, Maternal Employment, Childcare, EITC

JEL: H24, I12, J22

1. INTRODUCTION

Previous studies have found adverse effects of maternal employment on child obesity for mothers with higher levels of education and earnings but no effect for mothers with lower education and earnings (Anderson et al., 2003; Fertig et al, 2009; Ruhm, 2008). To improve our understanding of the nature of this apparent heterogeneity in the effects of maternal employment, the present study estimates the cumulative effect of maternal employment through the most general mechanism, non-parental childcare up to age 5, by mother’s education in a joint model of maternal employment, childcare, and obesity.

A key problem that hampers research in this area is the complicated selection problem arising due to correlation of maternal employment and childcare inputs with unobserved characteristics of mothers and children and concurrent correlation of these unobserved factors with children’s outcomes. First, working mothers whose children are in non-parental childcare may differ from working or non-working mothers whose children are not in non-parental childcare on unobserved factors that also affect the child’s risk of obesity. Second, a child’s obesity or obesity risk may affect maternal employment and childcare decisions. Because the empirical model in this study forms approximations to the mother’s employment and childcare decision rules and child physical production function, the resulting joint model of the employment-childcare decision and the child production function allows both sources of selection bias to be addressed.

Multiple instruments are employed to identify the effect of non-parental childcare on child obesity including period and state variations in Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) and fluctuations in local market conditions (state unemployment rate, the percentage of women in service occupations, and average wages). In the mid-1990s the generosity level of the EITC was increased significantly throughout the U.S., and several states adopted supplementary benefits in addition to the federal credit. Because the children in our study were born between 1987 and 1997, changes in EITC are a plausibly exogenous influence on mothers’ employment and childcare decisions during their children’s early years of life. Moreover, strong positive effects of EITC on maternal labor supply have previously been demonstrated (Meyer and Rosenbaum, 2001). Standard tests for validity and relevance provide additional support for our instrument selection (results not shown).

2. MODEL AND DATA

The optimal employment and childcare decision rules of the mother can be described by the following multinomial function:

| (1) |

where V is the value function which depends on all state variables s, consisting of X – child’s birth weight, sex of the child, mother’s age at birth, mother’s BMI and her participation during pregnancy in a variety of welfare programs such as WIC and Food Stamps, R – EITC rules and fluctuations in local market conditions, C – child’s childcare experience, W – mother’s employment history after birth, E – mother’s education, in four subgroups: less than high school diploma (below 12 years of education), high school diploma (12 years of education), some college (13 to 15 years of education), and bachelors and advanced degrees (16 and more years of education), and η – a combination of child unobserved heterogeneity, mother’s unobserved ability in home work, and mother’s taste for investments in the form of goods.

In the literature, more emphasis is given to exploring the effect of maternal input choices on the upper tail of the child percentile body mass index (BMI) distribution, and especially to BMI ≥ 95th percentile (“obese”). The probability that the child is obese at time t, Ot, can be given by the following logit equation.

| (2) |

Our empirical strategy, following Mroz (1999), is to jointly estimate (1) and (2) assuming M points of support to approximate the distribution of η. There are four equations in the model; therefore ηk consists of four vectors each representing the set of heterogeneity parameters in one of the equations. Conditional on mass point ηm = (η1m, η2m, η3m, η4m), mother-child pair i contributes to the likelihood function as follows:

| (3) |

The unconditional contribution for mother-child pair i is:

| (4) |

Where φm is a weight of mass point ηm. Finally, the likelihood function can now be written as follows:

| (5) |

The likelihood function is maximized with respect to all parameters as well as the individual’s specific mass points and weights. In each equation, we also include a constant term and normalize the individual mass point per equation to zero in order to identify the model. Finally, we compute a robust covariance matrix.

The interpretation of coefficients in non-linear models with interaction terms requires additional computation (Ai and Norton 2003). To quantify the effect of non-parental childcare by maternal education we use a simulation method. We assume that the entire set of estimated coefficients, mass points and mass point probabilities follow a multivariate normal distribution centered at the estimated values of the parameters with covariance matrix equal to the estimated covariance matrix for the entire set of parameters. We draw a set of normally distributed random variables from this distribution and recalculate the outcomes of the model with perturbed parameters. The above step is iterated 100 times and the average values for the main outcome of the model is computed.

We use the Panel Study of Income Dynamics (PSID) Core and Child Development Supplement (CDS) as our main data source (Institute for Social Research 2010). With it, we create a work history for each mother that tracks her employment status from the month of birth to the month when the child enters kindergarten, the childcare history of each child, and maternal and child demographic and health characteristics.

3. RESULTS

In Table 1, we report simulated probabilities of obesity by maternal education and childcare experience calculated using point estimates from a joint model. The simulated probability of obesity for the average child of the mothers with less than 12 years of schooling is 0.276 when the child has no exposure of non-parental childcare. The greater the child’s total exposure to non-parental childcare, the lower is the probability of obesity. After 60 months in childcare, the probability of obesity declines to 0.198. We observe a similar decline for the average child whose mother has only a high school diploma. With no experience in non-parental childcare, the probability of obesity is 0.245; after 60 months it is 0.167. For the average child whose mother has between 13 and 15 years of schooling, however, the probability of obesity is almost unchanging with non-parental child experience. Finally, for a child whose mother has at least a bachelor’s degree, the probability of obesity increases substantially as the child spends more time in a non-parental childcare setting. With no experience in any non-parental childcare setting, the probability of obesity is only 0.131, after 36 months in childcare, the probability goes to 0.176 and it further increases to 0.212 after 60 months in non-parental childcare.

Table 1.

Simulated probability of child obesity by maternal education and childcare duration

| Childcare in months | Less than 12 years | 12 years | 13–15 years | 16+ years | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean(SE) | Δ1 | Mean | Δ1 | Mean | Δ1 | Mean | Δ1 | |

| 0 | 0.28(0.03) | 0.25(0.02) | 0.23(0.02) | 0.13(0.02) | ||||

| 12 | 0.26(0.02) | −0.018** | 0.23(0.02) | −0.018** | 0.23(0.02) | 0.0 | 0.15(0.02) | 0.014** |

| 24 | 0.24(0.02) | −0.017** | 0.21(0.02) | −0.016** | 0.23(0.02) | 0.0 | 0.16(0.02) | 0.015** |

| 36 | 0.23(0.03) | −0.016** | 0.20(0.02) | −0.016** | 0.23(0.03) | 0.0 | 0.18(0.02) | 0.016** |

| 48 | 0.21(0.03) | −0.014** | 0.18(0.02) | −0.014** | 0.24(0.03) | 0.0 | 0.20(0.03) | 0.017** |

| 60 | 0.20(0.04) | −0.013* | 0.17(0.03) | −0.014** | 0.24(0.04) | 0.0 | 0.21(0.04) | 0.019** |

statistically significant at the 0.05 level

statistically significant at the 0.01 level

Δ is the difference between the simulated probabilities for cumulative childcare experience for n and n+12 months. For example, for the average mother with less than 12 years of education, an increase in childcare experience from 0 months to 12 months results in a 0.258–0.276=0.018 or 1.8% decrease in the probability of child obesity.

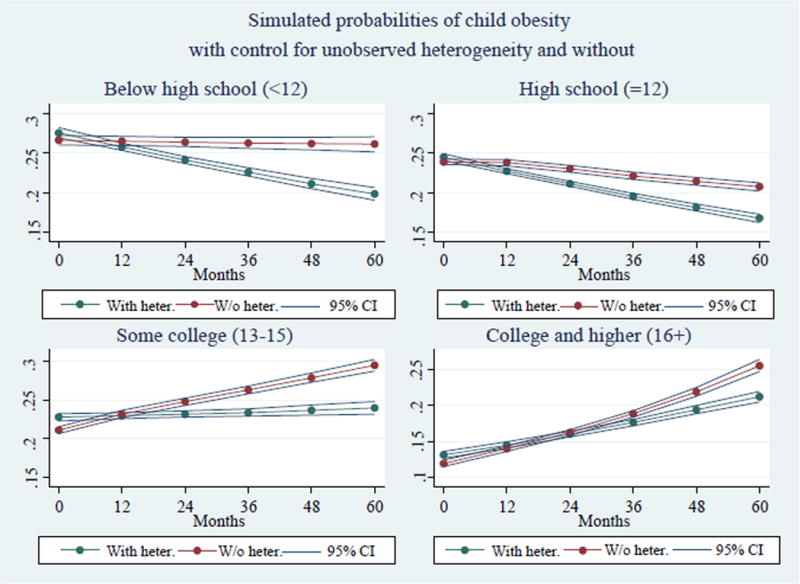

Additionally, Figure 1 shows that controlling for non-random selection of mothers into employment and childcare has changed substantially the profile of the obesity prevalence across all groups, but that the largest changes have occurred for children of mothers with less than 12 years schooling or with a high school diploma. When unobserved heterogeneity is ignored in estimation of parameters of the obesity equation, no association between childcare and the probability of obesity for lowest educated women is found. For women with 12 years of education this association is only marginal. The analogous comparison of the probabilities for more educated women demonstrates that accounting for unobserved heterogeneity eliminates the adverse effect of non-parental childcare on child obesity for women with some college education and reduces the adverse effect at higher cumulative amounts of non-parental care for women with college degrees.

Figure 1.

Simulated probabilities of child obesity by maternal education and childcare duration, with and without controlling for unobserved heterogeneity

4. DISCUSSION

Consistent with the direction of effect in previous studies, we found that children whose mothers had a college diploma or advanced degree, if placed in a non-parental childcare setting, would have a 1.4–1.8 % higher risk of obesity at the same ages. Additionally, however, we found that children whose mothers had 12 years of education or below if placed in a non-parental childcare setting for one year would have a 1.4–1.9 % lower risk of obesity at ages 2–18. This latter result was due to unobserved heterogeneity effects that were larger for women with 12 years of education and below. In particular, the flat relationship between months of childcare and probability of child obesity found when estimating the model without modeling the selection of women into employment and childcare turned into a strongly inverse relationship between months of childcare and probability of child obesity when modeling this selection. For the children of college graduate mothers, the strong positive relationship between months of childcare and probability of child obesity in the model without unobserved heterogeneity was reduced in its magnitude when modeling selection into employment and childcare, but the relationship remained positive.

Although taken together these findings are new, we argue that they are consistent both with the explanations previously offered to explain why only for higher-educated women have adverse effects of maternal employment on child obesity been found, and also with limited other evidence on favorable effects of center childcare targeted at the children of low-income families. Anderson et al. (2003) speculate that the positive effect of maternal employment on child obesity for highly educated mothers is due to lower skills of caregivers in childcare settings. The reverse may apply to lower-educated mothers. Higher education levels of caregivers in center care relative to that of children whose mothers with no more than a high school education may imply greater knowledge of healthier nutritional and physical activity regimes. Additionally, the childcare centers used by lower-education women frequently include those whose activity and nutrition programs are required to follow guidelines aimed at preventing obesity (Frisvold and Lumeng 2011).

Highlights.

We estimate a model of the mother’s employment-childcare decision and child obesity

State variations in EITC and fluctuations in local market are used as instruments

The effect of childcare on child obesity varies with maternal education

Children of highly educated mothers have a 1.4–1.8% higher risk of obesity

Children of least educated mothers have a 1.4–1.9% lower risk of obesity

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by U.S. National Institute of Child Health and Human Development grants R01-HD061967 and T32-HD007329.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Zafar E. Nazarov, Indiana University – Purdue University Fort Wayne.

Michael S. Rendall, University of Maryland, College Park.

References

- Ai C, Norton E. Interaction terms in logit and probit models. Economics Letters. 2003;80:123–129. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson P, Butcher K, Levine P. Maternal employment and overweight children. Journal of Health Economics. 2003;22:477–504. doi: 10.1016/S0167-6296(03)00022-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fertig A, Glomm G, Tchernis R. The connection between maternal employment and childhood obesity: Inspecting the mechanisms. Review of Economics of the Household. 2009;7:227–255. [Google Scholar]

- Frisvold D, Lumeng J. Expanding Exposure: Can Increasing the Daily Duration of Head Start Reduce Childhood Obesity? Journal of Human Resources. 2011;46(2):373–402. [Google Scholar]

- Institute for Social Research. Panel Study of Income Dynamics Child Development Supplement. 2010 http://psidonline.isr.umich.edu/CDS/

- Meyer B, Rosenbaum D. Welfare, the Earned Income Tax Credit, and the Labor Supply of Single Mothers. The Quarterly Journal of Economics. 2001;116(3):1063–1114. [Google Scholar]

- Mroz TA. Discrete Factor Approximations in simultaneous equation models: Estimating the impact of a dummy endogenous variable on a continuous outcome. Journal of Econometrics. 1999;92:233–274. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4076(98)00091-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruhm C. Maternal Employment and Adolescent Development. Labour Economics. 2008;15:958–983. doi: 10.1016/j.labeco.2007.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]