Abstract

NKT cells are a subpopulation of T lymphocytes with phenotypic properties of both T and NK cells and a wide range of immune effector properties. In particular, one subset of these cells, known as invariant NKT cells (iNKT cells), has attracted substantial attention because of their ability to be specifically activated by glycolipid antigens presented by a cell surface protein called CD1d. The development of synthetic α-galactosylceramides as a family of powerful glycolipid agonists for iNKT cells has led to approaches for augmenting a wide variety of immune responses, including those involved in vaccination against infections and cancers. Here, we review basic, preclinical and clinical observations supporting approaches to improving immune responses through the use of iNKT cell-activating glycolipids. Results from preclinical animal studies and preliminary clinical studies in humans identify many promising applications for this approach in the development of vaccines and novel immunotherapies.

Keywords: α-galactosylceramide, adjuvants, NKT cells, vaccine

NKT cells: definition & classification

NKT cells are a specialized group of T lymphocytes that have the ability to modulate the generation and outcome of a wide range of immune responses against pathogens, tumors, allergens and self antigens [1-4]. As their name implies, NKT cells have features of both conventional T cells as well as classic NK cells. Thus, they express CD3-associated αβ T-cell antigen receptors (TCRs), as well as multiple other cell surface receptors that are typically associated with natural killer NK cells such as CD161 (NK1.1), NKG2D and members of the Ly-49 family [3,5-9]. Like conventional T cells, NKT cells develop through a process that is dependent on thymic selection and are capable of specific antigen recognition, yet many of their functions imply that they are primarily a part of the innate immune system [6,9,10].

Several distinct subsets of NKT cells are currently recognized. Among these, type I NKT cells are the most extensively studied subpopulation. These are defined by their expression of a unique invariant TCRα chain (Vα14Jα18 in mice and Vα24Jα18 in humans), and are thus often referred to as invariant NKT cells (iNKT cells). Their TCRs are composed of this invariant TCRα chain paired with a limited repertoire of TCRβ chains (highly enriched for Vβ8, Vβ7, Vβ2 in mice and Vβ11 in humans) [10]. The TCRs of iNKT cells are selected for recognition of a variety of lipid and glycolipid antigens bound to the nonpolymorphic MHC class I-like molecule CD1d [10], which controls the thymic selection of iNKT cells, as well as their activation in many situations during immune responses [1,3,4,10]. Although less studied, type II NKT cells have also been identified as modulators of immunity against pathogens and tumors [11-13]. In contrast to iNKT cells, type II NKT cells express diverse TCRs that, to date, have been found to be indistinguishable from the highly diverse TCRs of conventional CD4 and CD8 T cells, and are thus also referred to as diverse NKT cells (dNKT cells). Like iNKT cells, these cells are also selected for CD1d-restricted lipid recognition, although available data indicate that they respond to different lipids than iNKT cells [12,14]. Finally, a third subpopulation, known as type III NKT cells, is recognized, which has similar phenotypic properties as the other two groups, but is not dependent on CD1d for development or antigen recognition [6]. In this review, we focus exclusively on the activities and functions of iNKT cells.

The frequency of iNKT cells has been well characterized in mice, where they comprise approximately 1–3% of the lymphocytes in the circulation and lymphoid organs (lymph nodes, spleen and thymus) and are strikingly enriched in the liver where they constitute up to approximately 30% of resident lymphocytes [15,16]. Notably, the frequency of iNKT cells in humans is approximately ten-times lower in tissues that have been examined, and the frequency in peripheral blood shows substantial variation between different individuals with a mean value of approximately 0.1% [17,18]. Although human and mouse iNKT cells display conserved phenotypic and functional features, this major difference in frequency has challenged the extrapolation of iNKT-cell based immunotherapy from mouse to humans. A few attempts to overcome this problem have used nonhuman primates to model in vivo iNKT-cell responses, as these animals generally have iNKT-cell numbers much closer to what is seen in humans [19,20]. Such studies are hindered by limitations in sample size, the lack of well-established tools for analyzing iNKT cell responses and the inability to perform genetic manipulations. These issues continue to encourage the development of humanized mouse models, such as the recently reported human CD1d knock-in mouse, which has functional iNKT cells at frequencies more similar to humans [21].

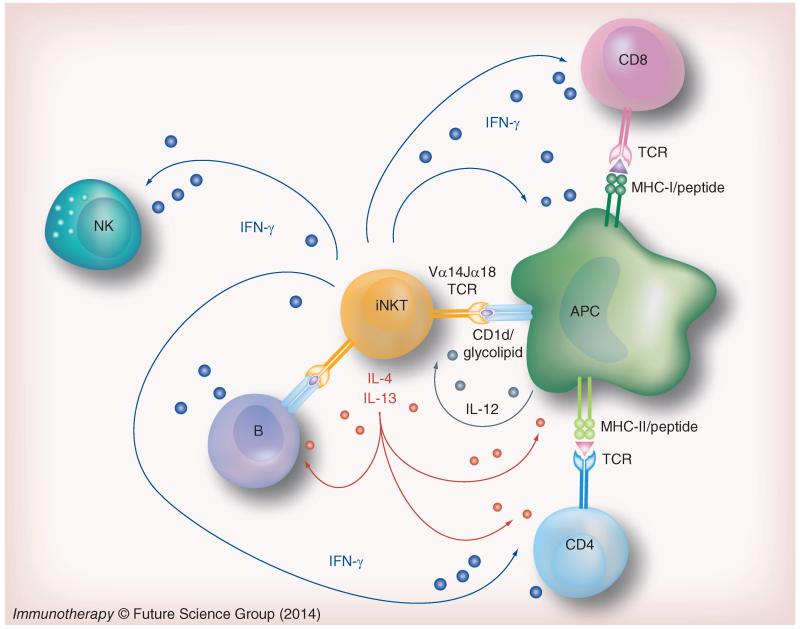

Upon activation, iNKT cells rapidly secrete a wide array of cytokines, including those that are generally associated with Th1-type responses (i.e., IFNγ and TNF), Th2-type responses (i.e., IL-4, IL-5 and IL-13) and Th17-type responses (i.e., IL-17A and IL-22) [22-26]. Their activation can be mediated by TCR ligation, or by a combination of TCR ligation and inflammatory cytokines such as IL-12 (Figure 1) [22,27]. In contrast to conventional T cells, iNKT cells are much less dependent on costimulation and they respond very rapidly after TCR engagement. This seems to be due to the partially activated state of the cells at baseline, and to their constitutive expression of preformed mRNA transcripts for cytokines such as IFNγ and IL-4 [28]. In fact, iNKT cells phenotypically resemble antigen-experienced memory T cells, with high expression of the activation markers CD44 and CD69 and low expression of CD62L [6,29]. However, this partially activated state does not require previous antigen recognition as it does for memory T cells. Another interesting feature of iNKT cells is that they are at least weakly stimulated by CD1d-expressing APCs without the addition of any exogenous foreign antigen [30,31]. This self-reactivity is believed to be important in both thymic selection and homeostatic maintenance of iNKT cells in the periphery, and most likely involves recognition of normal self lipids in complex with CD1d [32,33]. In addition, this self-reactivity may be involved in the contribution of iNKT cells to immune tolerance by stimulating secretion of predominantly anti-inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-4 and IL-13 [25,34]. Although iNKT cells can express several cytotoxic effector molecules in response to activation such as perforin, granzymes and Fas ligand, their major function appears to be the modulation of immune responses by the rapid production of effector cytokines [35]. In the context of infection or in response to tumors, iNKT cells rapidly secrete large amounts of proinflammatory cytokines, such as IFNγ, TNF and GM-CSF [22]. These cytokines can induce the secondary activation, also referred to as transactivation, of several types of immune cells including dendritic cells (DCs), NK cells, B cells and CD4 and CD8 T cells (Figure 1) [10,36-39], thereby amplifying the immune response. This ability to induce the transactivation of other immune cell types endows iNKT cells with a remarkable ability to bridge innate and adaptive immune responses.

Figure 1. Invariant NKT cells and their role in immunity.

iNKT cells express a characteristic antigen receptor that includes an invariant TCRα chain. These TCRs recognize specific glycolipid ligands bound to CD1d molecules, which are expressed mainly on APCs such as dendritic cells and B lymphocytes. After TCR ligation, iNKT cells rapidly secrete multiple Th1 and Th2 type cytokines, such as IFNγ and IL-4. These cytokines, along with surface molecules expressed on activated iNKT cells, influence the activity of many other cells in the immune system, and contribute to transactivation of NK cells, maturation of DCs and enhancement of specific T-cell and B-cell responses and memory.

iNKT: Invariant NKT; TCR: T-cell receptor.

Glycolipid antigens recognized by iNKT cells

Since iNKT cells can secrete a large variety of cytokines and also influence other key cell types in immunity, the identification and design of glycolipid antigens to modulate their function has been an area of extensive research. The ability of iNKT cells to respond under certain conditions to normal cells expressing CD1d is believed to reflect their recognition of self lipids. Although extensive research has sought to identify the endogenous ligands recognized by iNKT cells, this is still an area that remains to be completely resolved [40]. Among the endogenous lipid and phospholipid candidates, cellular glycosylphosphatidylinositols (GPIs) and glycosphingolipids with special emphasis on isoglobotrihexosylceramide (iGb3) have been proposed to be responsible for iNKT cell selection and homeostatic maintenance [41-43]. However, several aspects of these studies have been controversial. For instance, it has been shown that mice deficient in the production of iGb3 do not have iNKT cell defects in ontogeny or function [44,45]. Similarly, humans have been reported to lack iGb3 due to a functional deficiency of the enzyme iGb3 synthase. Although it has been proposed that an alternative pathway for iGb3 synthesis could exist in humans, there is a lack of consistency in the reports that have tried to detect iGb3 in the thymus and peripheral lymphoid organs [46,47]. In addition, detailed studies of the 3D structures of human CD1d and iNKT cell TCRs have suggested structural constraints that may prevent efficient recognition of iGb3 by human iNKT cells [48]. Moreover, the expression of iGb3 seems to be tightly regulated to minimal levels in animals with functional iGb3 synthase such as pigs, suggesting an immune selection pressure on this ligand during evolution [49]. More recently, β-glucosylceramide (β-GluCer) has been identified as a self-lipid that stimulates most human and mouse type I NKT cells and also a fraction of type II NKT cells, suggesting a role for this ligand in controlling NKT-cell selection and homeostasis [50,51]

Compared to studies of self-lipid ligands, more extensive and consistent results have been obtained from studies on the exogenous lipid antigens recognized by iNKT cells. These include several microbial-derived iNKT cell ligands, including glycolipids from Mycobacterium bovis, Borrelia burgdorferi, Sphingomonas species, Leishmania donovani and Streptococcus pneumonia [36,40,52-55]. A discussion of the structures and activities of the specific iNKT cell antigens produced by these microbes is beyond the scope of this review, but has been covered thoroughly elsewhere in the literature [40]. Here we focus mainly on synthetic ligands for activation of iNKT cells, which currently represent the main approach to development of clinically applicable therapeutic agents.

A key discovery for iNKT-cell biology was the observation that α-galactosylceramides from extracts of the marine sponge Agelas mauritianus are able to potently activate virtually all iNKT cells [56]. The subsequent development of a synthetic form of α-galactosylceramide (αGalCer), a glycolipid designated KRN7000 with the structure (2S,3S,4R)-1-O-(d-galactosyl)-N-hexacosanoyl-2-amino-1,3,4-octadecanetriol (Table 1), provided, for the first time, the ability to induce a robust activation of iNKT cells in vitro and in vivo [56,57]. Since KRN7000 binds to CD1d to form a complex with very high affinity for the TCRs of mouse or human iNKT cells, this compound also enabled the accurate detection and quantitation of iNKT cells by using fluorescently-labeled KRN7000-loaded CD1d tetramers for flow cytometry [58,59].

Table 1.

Examples of α-galactosylceramide synthetic analogs and their cytokine biasing properties.

| Name | Structure | Cytokine bias |

Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| KRN7000 |

|

Th1 + Th2 | [56,57] |

|

α

GalCer

C24:0 |

|

Th1 + Th2 | [63] |

| α-C-GalCer |

|

Th1 | [64] |

| α-Carba- GalCer |

|

Th1 | [65] |

| 7DW8-5 |

|

Th1 | [66,67] |

|

α

GalCer

C20:4 |

|

Th2 | [63] |

|

α

GalCer

C20:2 |

|

Th2 | [63,70] |

|

α

GalCer

C10:0 |

|

Th2 | [60] |

αGalCer: α-galactosylceramide.

Structurally, KRN7000 contains an α-galactose bound by a 1′-O-glycosidic bond to a C18 phytosphingosine base with an amide-linked, fully saturated C26 fatty acyl chain (Table 1). The in vivo administration of KRN7000 to mice leads to a mixed Th1 and Th2 type cytokine response, with significant amounts of both IFNγ and IL-4 becoming detectable in the serum within a couple of hours post-injection [60]. The mixed in vivo response induced by KRN7000 classified this compound as a Th0-type iNKT-cell ligand [60,61]. Subsequently, multiple structural analogs of KRN7000 have been developed that more selectively induce either Th1 or Th2 biased cytokine responses by iNKT cells. These analogs incorporate a range of chemical modifications, including modifications in the sphingosine chain, the N-acyl chain, the glycosidic bond and in the carbohydrate moiety (Table 1) [40,60,61].

The first functionally distinct analog of αGalCer to be identified was a compound designated as OCH, which has a substantially truncated 9 carbon sphingosine chain and a slightly shortened 24 carbon N-linked acyl chain compared with KRN7000 [62]. This compound elicits a Th2-type cytokine bias, a property which is also shared by the compound αGalCer C20:2 which has a shorter and less saturated fatty acyl chain [63]. On the other hand, the compound α-C-GalCer, which is a C-glycoside analog of KRN7000, elicits a Th1 type cytokine bias, and also has been found to be as much as 1000-fold more potent than KRN7000 at reducing metastasis in a mouse model of melanoma [64]. This enhanced potency may be due in part to increased stability that is conferred by the C-glycoside linkage [64]. A similar effect has been observed with replacement of the oxygen in the galactose ring with carbon to create a so-called carbasugar analog of KRN7000 [65]. Recently, another novel form of αGalCer known as 7DW8–5, which possesses a shorter acyl chain with 11 carbons terminating in a fluorinated benzene ring (Table 1), has been shown to elicit much higher activity as an adjuvant in malaria and HIV vaccines than KRN7000, making it a leading candidate for advancement into clinical trials [66,67].

Rational design of glycolipids as immunomodulators

The identification of synthetic αGalCer analogs with the ability to induce a predominant Th1 or Th2 bias and the mechanisms leading to their differing effects on iNKT cells have been extensively studied. The understanding of these mechanisms may aid the rational design and screening of potent forms of αGalCer with more precise and predictable effects on immune responses. Although much remains to be learned in this important area, current findings have identified several mechanisms contributing to control of the quality of iNKT-cell responses. These include effects of glycolipid structure on TCR affinity, and effects on the kinetics and pathways involved in CD1d-mediated presentation of glycolipids.

Early studies addressing the role of TCR affinity in the quality of iNKT-cell responses initially suggested a simple model, in which low affinities account for Th2 bias and high affinities of TCR interaction favor Th1 bias [68,69]. According to this model, partial signaling through TCR, which is achieved by low affinity TCR/CD1d-glycolipid interaction, induces the signaling required for Th2 biasing and lacks the stronger or more sustained signaling necessary for the induction of Th1 bias by compounds with high TCR affinities. In the case of mixed Th1 and Th2 responses, as for KRN7000, this model suggests that these compounds have an intermediate affinity that fails to surpass the threshold required to make induce Th1 signaling while overcoming the Th2 component. Although some analogues of αGalCer conform to this affinity model, many exceptions have also been documented [60,69-72]. The influence of other kinetics parameters that have been shown to be important for activation of T cells, such as the half-life of TCR binding to its ligand and ligand density [73,74], remains to be determined for iNKT cells. Recently, it has been shown that bias in NKT cell cytokine secretion could be to some extent determined by the development of different lineages of iNKT cells, namely NKT1, NKT2 and NKT17 cells [75], during early stages of thymic development. However, whether these iNKT-cell lineages respond differentially to Th1 versus Th2 biasing αGalCer analogs remains to be determined.

The uptake and presentation of glycolipids by APCs also play an important role in determining their cytokine bias. It has been shown that glycolipids that induce Th1 cytokine responses must be internalized and transported into endosomes to be presented. This process is dependent on acidic pH of endosomal compartments and on a variety of intracellular lipid transfer proteins [76-78]. In contrast, Th2 biasing compounds do not require any of these factors and can be loaded directly onto CD1d proteins at the cell surface [63]. This remarkable difference can be explained by the fact that Th2 biasing analogs of αGalCer have chemical modifications that increase their polarity and reduce their hydrophobicity, such as shorter N-acyl chains and polar substitutions (double bonds and oxygen-containing groups) [60]. Interestingly, the dependency on endosomal trafficking for Th1 biasing compounds correlates with the findings that Th1 compounds are loaded into CD1d molecules that then accumulate in lipid rafts on the APC plasma membrane, whereas Th2 compounds are loaded onto CD1d molecules that are excluded from lipid rafts [60]. Thus, lipid raft localization seems to be an important factor to favor the cell signaling required to induce a Th1 bias [60,61]. Based on this principle, a recent study from our group has shown that a fluorescence-based assay to determine lipid raft localization of an extensive library of αGalCer analogs correctly predicted their cytokine biasing properties [61]. Thus, lipid raft localization seems not only to be one major mechanism responsible for cytokine biasing, but also provides the basis for a powerful tool in the functional screening of new glycolipid compounds.

Potentiating immune responses by iNKT-cell activation

The ability of activated iNKT cells to generate potent adjuvant effects in a variety of settings is to a great extent attributable to enhancement in the activity of adaptive immune cells such as DCs, T cells and B cells [10,36-39]. It has been reported that following the injection of αGalCer in vivo, DCs upregulate costimulatory molecules such as CD40, CD80 and CD86, and secrete proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-12 and TNF-α. These changes constitute an adjuvant cascade that increases the activation of peptide antigen-specific CD4 and CD8 T cells [79,80]. The adjuvant effects of αGalCer are dependent on iNKT cells and require the interaction between CD40 on the DC with CD40L on the iNKT-cell surface [81]. This amplification of T-cell responses has been found to be particularly pronounced in the crosspriming of CD8 T-cell responses both in mouse and nonhuman primate models [20,82].

In addition to the effects on T cells, the activation of iNKT cells also enhances antibody production by B cells. There is evidence that iNKT cells are involved in driving antibody production in several allergy and pathogen infection models [83-85]. It has been shown that the administration of αGalCer leads to an increase in plasma IgE levels, probably due to the contribution of iNKT cell-derived Th2-type cytokines [86]. Importantly, in combination with different protein antigens, it has been shown that αGalCer enhances the titers of IgG antibodies [87] and increases the generation and persistence of plasma cells [87,88]. Although these results have been validated in vivo so far only in mouse models, it is notable that the stimulation of human peripheral blood in culture with αGalCer induces antibody production [89]. Several mechanisms may be responsible for the enhancement of B cell activity by iNKT cells. One possibility is that iNKT cells can substitute for conventional CD4 T-cell help through a process involving direct interactions between glycolipd/CD1d complexes on B cells and TCRs on NKT cells. This is supported by the observation that CD1d expression by B cells is required for iNKT cell-induced antibody enhancement [90,91]. On the other hand, the ability of activated iNKT cells to stimulate copious IFNγ production by NK cells may contribute to IgG production by B cells [92].

Potential clinical applications of iNKT-cell activators

Due to the ability of glycolipids like αGalCer to enhance or redirect immune responses, they have been studied extensively as immunomodulators in various animal models of disease and disease prevention. This includes many studies evaluating their use in combination with vaccines against various infectious diseases [64,66,67,93-99]. For example, KRN7000 has been shown to improve immune responses against malaria parasites when combined with several different antimalaria vaccines, such as irradiated sporozoites or malaria antigens expressed by viral vectors [93]. Here, the adjuvant activity of KRN7000 was mainly mediated by iNKT-derived IFNγ production. This conclusion is reinforced by the finding that combining an antimalaria vaccine with the C-glycoside analog of αGalCer (α-C-GalCer), which elicits a strongly Th1 cytokine biased iNKT-cell response, increased the immunogenicity by as much as 1000-fold [64]. The novel 7DW8–5 analog of αGalCer has also been shown to be at least 100-fold more active at stimulating human and mouse iNKT cells, and to elicit potent enhancement of malaria vaccines that exceeds the immunogenicity achieved using KRN7000 [66,67]. Importantly, a recent report showed that coadministration of 7DW8–5 with a human malaria vaccine candidate in nonhuman primates significantly enhances malaria-specific CD8 T-cell responses, reinforcing the use of this glycolipid in future clinical trials [20]. These results support the notion that iNKT-cell activation enhances CD8 T cell crosspriming in non-human primates, in contrast to another recent report that failed to find a similar effect using KRN7000 in the context of viral infections [19].

Combining αGalCer with several antiviral vaccines has also been shown to greatly enhance their immunogenicity. For example, KRN7000 administered in combination with an HIV-1 DNA vaccine encoding env and gag proteins greatly enhances both CD4- and CD8-specific T-cell responses, as well as the antibody responses against these lentiviral proteins [99]. Studies using an influenza virus challenge model in mice have yielded similar studies, and also allow the assessment of host protection. For instance, immunization with influenza virus hemagglutinin (HA) or inactivated influenza virus in combination with KRN7000 enhances mucosal and systemic humoral immune responses to the virus, thus favoring viral clearance and survival [94-96]. Although it was initially proposed that the Th2 cytokines induced by KRN7000 were responsible for the improved antiviral immunity [95], other studies have indicated that αGalCer analogs that deliver a strong Th2 bias may be less effective as adjuvants for a live attenuated influenza vaccine when compared directly to KRN7000 [98]. In addition, the combination of an influenza vaccine with the Th1 biasing compound α-C-GalCer has proven to be very effective [97]. This may be related to the increased antiviral CD8 T-cell responses that are stimulated by this glycolipid.

In addition to their use as adjuvants in vaccines against infectious agents, iNKT cell-activating glycolipids have been also used in models of tumor immunotherapy with promising results. Initial studies using KRN7000 as a simple intravenous injection in mice demonstrated the profound ability of this agent to induce anticancer immunity [57]. Subsequent studies using variations of this approach showed the potential for further improvements. For example, when administered systemically following B16 melanoma injection in mice, α-C-GalCer was shown to induce a significant reduction in tumor growth and metastasis [64]. Similarly, KRN7000 greatly enhanced the antitumor activity induced by immunization with antigen-loaded DCs in a mouse model of hepatocellular carcinoma [100]. Many other studies in mouse cancer models have confirmed the potential of αGalCer as tumor vaccine adjuvants [101-104].

Although experience with iNKT cell-activating glycolipids in vivo in humans is currently quite limited, several Phase I clinical trials have been conducted using KRN7000 primarily for treatment in patients with advanced cancers, and also for assessment as a potential therapeutic agent against chronic hepatitis B and hepatitis C infections [105-111]. In these studies, direct intravenous administration of KRN7000 was shown to be well tolerated over a range of dosages, and evidence of significant immune activation in vivo was obtained. However, such treatments did not result in clearly detectable clinical benefits against cancer or chronic viral hepatitis. Subsequent trials have attempted to improve the efficacy of KRN7000 in cancer patients by using infusions of autologous DCs pulsed ex vivo with KRN7000 [109]. These trials again provided evidence for immune activation that was consistent with human iNKT-cell responses in vivo, but failed to display any clearly significant antitumor effect. More recent trials have begun to consider the potential importance of boosting the numbers and functionality of iNKT cells in patients with advanced cancer, who harbor a variety of immunological defects. Thus, in one recent phase I clinical trial, APCs were pulsed with KRN7000 in the presence of autologous iNKT cells, which were then injected back into cancer patients. This approach, using intra-arterial infusion of activated Vα24 NKT cells directly into tumors along with submucosal injection of KRN7000-pulsed autologous DCs, induced significant antitumor immunity and had measurable beneficial clinical effects in advanced head and neck squamous cell carcinoma [108]. These findings, while preliminary, suggest that iNKT-cell activators have the potential to deliver clinically relevant anticancer effects, and provide a strong rationale for further studies in this area.

Optimizing delivery methods for iNKT cell-activating glycolipids

Efforts to improve the potential therapeutic uses of iNKT cell-activating glycolipids in the future will likely continue to focus on the design of more potent analogs and on optimizing their delivery in vaccine formulations. One problem that has been recognized is the induction of iNKT-cell unresponsiveness or anergy that often occurs with strong glycolipid agonists, particularly after repeated administration [27,105,112,113]. This feature of the iNKT-cell response can limit the use of such agonists in settings that may require repeated doses for optimal effect, as appears to be the case in tumor immunotherapy. Some strategies aimed at avoiding iNKT-cell anergy include the targeting of glycolipid agonists specifically to DCs, thus avoiding their presentation by B cells which are thought to be high inducers of iNKT-cell anergy [112,114]. Such targeted delivery may also help to avoid the potential toxicities of systemic activation of iNKT cells, which, at least in mouse models, have included liver damage and potentiation of sepsis [115].

Recently, several experimental approaches have been developed to assist in targeting the delivery of αGalCer to specific sites for more directed activation of iNKT cells. One relatively simple and effective delivery method which ameliorates both iNKT-cell anergy induction and glycolipid toxicity, is the direct incorporation of glycolipids into bacterial membranes as an adjuvant for live attenuated bacterial vaccines [82]. The incorporation of both KRN7000 and α-C-GalCer into the attenuated Mycobacterium bovis vaccine strain BCG induced the maturation of DCs and greatly enhanced the activation of antigen specific CD8 T cells [82]. Another improved strategy for delivery of glycolipid antigens has been the use of specific-antibody/CD1d fusion proteins that are loaded ex vivo with αGalCer [116]. The administration of a KRN7000 pulsed CD1d protein fused with an anti-HER2 single-chain antibody Fv fragment (scFv) induces a potent antitumor response in a mouse tumor model using HER2-expressing B16 melanoma cells [116]. Importantly, repeated injections of this fusion protein lead to sustained iNKT-cell activation with reduced anergy induction. More work is needed on optimizing the directed delivery of iNKT-cell activators, which may allow the full therapeutic benefit of this approach to be captured without provoking unwanted toxic effects.

Conclusion & future perspective

The discovery of CD1d presentation of glycolipid antigens to iNKT cells has led to rapid accumulation of knowledge on how these cells may participate in immune responses. The ability to specifically activate and manipulate the responses of iNKT cells by using synthetic glycolipids of the αGalCer family has opened many potential avenues for therapeutic development. In mouse models, iNKT-cell activators can induce many beneficial effects that improve the efficacy of vaccines against infectious microbes and cancers. Translating these findings to humans remains a major challenge, and may await the development of better animal models to accurately replicate the iNKT-cell response in humans. However, it is already clear that the range of functional activities of iNKT cells in humans shares many of the essential features that have been documented in mice, and methods for harnessing the ability of iNKT cell-activating glycolipids in vaccination or immunotherapy in humans appear feasible. Efforts to optimize the structures of iNKT-cell ligands are continuing, particularly with the synthesis and evaluation of large numbers of analogs of αGalCer. While these remain the most powerful and specific class of ligands for iNKT cells identified to date, it is likely that other classes of lipids or even nonlipidic ligands remain to be discovered. In addition to further identification and refinement of ligand structure, the development of better methods for targeting iNKT-cell activators to specific sites of immunization and to induce more precise immune effector activities are also important areas for future development.

Executive summary.

Invariant NKT cells & their ligands

Invariant NKT cells (iNKT cells) represent a specialized group of T lymphocytes that share phenotypic features with T cells and NK cells.

iNKT cells express an invariant T-cell receptor (TCR)α chain and recognize glycolipids bound to CD1d molecules on the surface of APCs.

Activation of iNKT cells leads to the rapid secretion of multiple cytokines, including those typical of both Th1 and Th2 responses, such as IFNγ and IL-4.

Activation of iNKT cells also causes transactivation of other immune cells, such as dendritic cells, T cells and B cells, thereby enhancing cellular and humoral immune responses.

The synthetic α-galactosylceramide (αGalCer), known as KRN7000, is a strong agonist of iNKT cells, and induces the secretion of both Th1-type and Th2-type cytokines.

Multiple analogs of KRN7000 containing a range of different chemical modifications have been developed with the aim of more precisely controlling the quality of iNKT-cell responses.

Mechanisms of glycolipid-induced iNKT-cell cytokine biasing

The affinity of the TCR/CD1d interaction does not correlate with the cytokine bias induced by different αGalCer analogs.

Th1 biasing glycolipids must be internalized and transported into endosomes where they are loaded into CD1d molecules, whereas Th2 biasing glycolipids can be loaded into cell surface CD1d molecules.

Th1 biasing glycolipids are presented predominantly by CD1d molecules that are localized in plasma membrane lipid rafts.

Lipid raft localization is a powerful tool to screen novel glycolipid compounds for functional effects on iNKT-cell responses.

Clinical applications of iNKT-cell activators & novel strategies to enhance their activity

KRN7000 and other αGalCer analogs have been widely used as adjuvants to enhance the immune responses against viral, parasitic and bacterial pathogens, as well as for cancer immunotherapy.

Human clinical trials with αGalCer have been initiated as experimental approaches to immunotherapy of cancer and viral hepatitis.

- Improvement of the adjuvant activity of αGalCer is being attempted through methods that decrease toxicity and lead to less anergy induction of iNKT cells. Efforts are also being made to optimize delivery of αGalCer, including:

-

-Targeting to dendritic cells;

-

-Incorporation into live bacterial vaccines;

-

-Tumor-specific antibodies fused to CD1d molecules.

-

-

Footnotes

Financial & competing interests disclosure

S Porcelli is a paid consultant for Vaccines, Inc., which has commercial interest in the area of iNKT cell-based therapeutics and vaccines. The authors were supported by grants from NIH/NIAID (RO1 AI45889, RO1 AI093649 and PO1 AI063537). LJ Carreño is a Pew Latin American Fellow. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

No writing assistance was utilized in the production of this manuscript.

References

Papers of special note have been highlighted as:

• of interest

•• of considerable interest

- 1.Behar SM, Porcelli SA. CD1-restricted T cells in host defense to infectious diseases. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 2007;314:215–250. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-69511-0_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Crowe NY, Coquet JM, Berzins SP, et al. Differential antitumor immunity mediated by NKT cell subsets in vivo. J. Exp. Med. 2005;202(9):1279–1288. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Taniguchi M, Harada M, Kojo S, Nakayama T, Wakao H. The regulatory role of Valpha14 NKT cells in innate and acquired immune response. Ann. Rev. Immunol. 2003;21:483–513. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.21.120601.141057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wu L, Van Kaer L. Natural killer T cells and autoimmune disease. Curr. Mol. Med. 2009;9(1):4–14. doi: 10.2174/156652409787314534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arase H, Arase N, Saito T. Interferon gamma production by natural killer (NK) cells and NK1.1+ T cells upon NKR-P1 cross-linking. J. Exp. Med. 1996;183(5):2391–2396. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.5.2391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bendelac A, Savage PB, Teyton L. The biology of NKT cells. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2007;25:297–336. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.25.022106.141711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Godfrey DI, Macdonald HR, Kronenberg M, Smyth MJ, Van Kaer L. NKT cells: what’s in a name? Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2004;4(3):231–237. doi: 10.1038/nri1309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gumperz JE, Miyake S, Yamamura T, Brenner MB. Functionally distinct subsets of CD1d-restricted natural killer T cells revealed by CD1d tetramer staining. J. Exp. Med. 2002;195(5):625–636. doi: 10.1084/jem.20011786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kronenberg M, Gapin L. The unconventional lifestyle of NKT cells. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2002;2(8):557–568. doi: 10.1038/nri854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bricard G, Porcelli SA. Antigen presentation by CD1 molecules and the generation of lipid-specific T cell immunity. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2007;64(14):1824–1840. doi: 10.1007/s00018-007-7007-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baron JL, Gardiner L, Nishimura S, Shinkai K, Locksley R, Ganem D. Activation of a nonclassical NKT cell subset in a transgenic mouse model of hepatitis B virus infection. Immunity. 2002;16(4):583–594. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00305-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Behar SM, Podrebarac TA, Roy CJ, Wang CR, Brenner MB. Diverse TCRs recognize murine CD1. J. Immunol. 1999;162(1):161–167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Terabe M, Swann J, Ambrosino E, et al. A nonclassical non-Valpha14Jalpha18 CD1d-restricted (type II) NKT cell is sufficient for down-regulation of tumor immunosurveillance. J. Exp. Med. 2005;202(12):1627–1633. doi: 10.1084/jem.20051381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jahng A, Maricic I, Aguilera C, Cardell S, Halder RC, Kumar V. Prevention of autoimmunity by targeting a distinct, noninvariant CD1d-reactive T cell population reactive to sulfatide. J. Exp. Med. 2004;199(7):947–957. doi: 10.1084/jem.20031389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bendelac A, Rivera MN, Park SH, Roark JH. Mouse CD1-specific NK1 T cells: development, specificity, and function. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 1997;15:535–562. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.15.1.535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brigl M, Brenner MB. CD1: antigen presentation and T cell function. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2004;22:817–890. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.22.012703.104608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Im JS, Kang TJ, Lee SB, et al. Alteration of the relative levels of iNKT cell subsets is associated with chronic mycobacterial infections. Clin. Immunol. 2008;127(2):214–224. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2007.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sandberg JK, Bhardwaj N, Nixon DF. Dominant effector memory characteristics, capacity for dynamic adaptive expansion, and sex bias in the innate Valpha24 NKT cell compartment. Eur. J. Immunol. 2003;33(3):588–596. doi: 10.1002/eji.200323707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fernandez CS, Jegaskanda S, Godfrey DI, Kent SJ. In-vivo stimulation of macaque natural killer T cells with alpha-galactosylceramide. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2013;173(3):480–492. doi: 10.1111/cei.12132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20•.Padte NN, Boente-Carrera M, Andrews CD, et al. A glycolipid adjuvant, 7DW8-5, enhances CD8+ T cell responses induced by an adenovirus-vectored malaria vaccine in non-human primates. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(10):e78407. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0078407. First nonhuman primate preclinical study showing the efficiency of αGalCer analog 7DW8-5 as a vaccine adjuvant.

- 21••.Wen X, Rao P, Carreno LJ, et al. Human CD1d knock-in mouse model demonstrates potent antitumor potential of human CD1d-restricted invariant natural killer T cells. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2013;110(8):2963–2968. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1300200110. Development and chareacterization of a partially humanized model for NKT-cell responses.

- 22.Brigl M, Bry L, Kent SC, Gumperz JE, Brenner MB. Mechanism of CD1d-restricted natural killer T cell activation during microbial infection. Nat. Immunol. 2003;4(12):1230–1237. doi: 10.1038/ni1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Coquet JM, Chakravarti S, Kyparissoudis K, et al. Diverse cytokine production by NKT cell subsets and identification of an IL-17-producing CD4-NK1.1-NKT cell population. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105(32):11287–11292. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801631105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Goto M, Murakawa M, Kadoshima-Yamaoka K, et al. Murine NKT cells produce Th17 cytokine interleukin-22. Cell. Immunol. 2009;254(2):81–84. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2008.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Im JS, Tapinos N, Chae GT, et al. Expression of CD1d molecules by human schwann cells and potential interactions with immunoregulatory invariant NK T cells. J. Immunol. 2006;177(8):5226–5235. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.8.5226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Michel ML, Keller AC, Paget C, et al. Identification of an IL-17-producing NK1.1(neg) iNKT cell population involved in airway neutrophilia. J. Exp. Med. 2007;204(5):995–1001. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Uldrich AP, Crowe NY, Kyparissoudis K, et al. NKT cell stimulation with glycolipid antigen in vivo: costimulation-dependent expansion, Bim-dependent contraction, and hyporesponsiveness to further antigenic challenge. J. Immunol. 2005;175(5):3092–3101. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.5.3092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stetson DB, Mohrs M, Reinhardt RL, et al. Constitutive cytokine mRNAs mark natural killer (NK) and NK T cells poised for rapid effector function. J. Exp. Med. 2003;198(7):1069–1076. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Matsuda JL, Gapin L, Fazilleau N, Warren K, Naidenko OV, Kronenberg M. Natural killer T cells reactive to a single glycolipid exhibit a highly diverse T cell receptor beta repertoire and small clone size. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2001;98(22):12636–12641. doi: 10.1073/pnas.221445298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bendelac A, Lantz O, Quimby ME, Yewdell JW, Bennink JR, Brutkiewicz RR. CD1 recognition by mouse NK1+ T lymphocytes. Science. 1995;268(5212):863–865. doi: 10.1126/science.7538697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Exley M, Garcia J, Balk SP, Porcelli S. Requirements for CD1d recognition by human invariant Valpha24+ CD4− CD8-T cells. J. Exp. Med. 1997;186(1):109–120. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.1.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cohen NR, Garg S, Brenner MB. Antigen presentation by CD1 lipids, T cells, and NKT cells in microbial immunity. Adv. Immunol. 2009;102:1–94. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2776(09)01201-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Matsuda JL, Gapin L, Sidobre S, et al. Homeostasis of V alpha 14i NKT cells. Nat. Immunol. 2002;3(10):966–974. doi: 10.1038/ni837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sakuishi K, Oki S, Araki M, Porcelli SA, Miyake S, Yamamura T. Invariant NKT cells biased for IL-5 production act as crucial regulators of inflammation. J. Immunol. 2007;179(6):3452–3462. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.6.3452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Godfrey DI, Kronenberg M. Going both ways: immune regulation via CD1d-dependent NKT cells. J. Clin. Invest. 2004;114(10):1379–1388. doi: 10.1172/JCI23594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Carnaud C, Lee D, Donnars O, et al. Cutting edge: Cross-talk between cells of the innate immune system: NKT cells rapidly activate NK cells. J. Immunol. 1999;163(9):4647–4650. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fujii S, Shimizu K, Hemmi H, Steinman RM. Innate Valpha14(+) natural killer T cells mature dendritic cells, leading to strong adaptive immunity. Immunol. Rev. 2007;220:183–198. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2007.00561.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kitamura H, Ohta A, Sekimoto M, et al. alpha-galactosylceramide induces early B-cell activation through IL-4 production by NKT cells. Cell. Immunol. 2000;199(1):37–42. doi: 10.1006/cimm.1999.1602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nishimura T, Kitamura H, Iwakabe K, et al. The interface between innate and acquired immunity: glycolipid antigen presentation by CD1d-expressing dendritic cells to NKT cells induces the differentiation of antigen-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes. Int. Immunol. 2000;12(7):987–994. doi: 10.1093/intimm/12.7.987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Venkataswamy MM, Porcelli SA. Lipid and glycolipid antigens of CD1d-restricted natural killer T cells. Semin. Immunol. 2010;22(2):68–78. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2009.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gumperz JE, Roy C, Makowska A, et al. Murine CD1d-restricted T cell recognition of cellular lipids. Immunity. 2000;12(2):211–221. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80174-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Joyce S, Woods AS, Yewdell JW, et al. Natural ligand of mouse CD1d1: cellular glycosylphosphatidylinositol. Science. 1998;279(5356):1541–1544. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5356.1541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhou D, Mattner J, Cantu C, 3rd, et al. Lysosomal glycosphingolipid recognition by NKT cells. Science. 2004;306(5702):1786–1789. doi: 10.1126/science.1103440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Christiansen D, Milland J, Mouhtouris E, et al. Humans lack iGb3 due to the absence of functional iGb3-synthase: implications for NKT cell development and transplantation. PLoS Biol. 2008;6(7):e172. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Porubsky S, Speak AO, Luckow B, Cerundolo V, Platt FM, Grone HJ. Normal development and function of invariant natural killer T cells in mice with isoglobotrihexosylceramide (iGb3) deficiency. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104(14):5977–5982. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611139104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Li Y, Teneberg S, Thapa P, Bendelac A, Levery SB, Zhou D. Sensitive detection of isoglobo and globo series tetraglycosylceramides in human thymus by ion trap mass spectrometry. Glycobiology. 2008;18(2):158–165. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwm129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Speak AO, Salio M, Neville DC, et al. Implications for invariant natural killer T cell ligands due to the restricted presence of isoglobotrihexosylceramide in mammals. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104(14):5971–5976. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607285104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sanderson JP, Brennan PJ, Mansour S, et al. CD1d protein structure determines species-selective antigenicity of isoglobotrihexosylceramide (iGb3) to invariant NKT cells. Eur. J. Immunol. 2013;43(3):815–825. doi: 10.1002/eji.201242952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tahiri F, Li Y, Hawke D, et al. Lack of iGb3 and Isoglobo-Series glycosphingolipids in pig organs used for xenotransplantation: implications for natural killer T-cell biology. J. Carbohydr. Chem. 2013;32(1):44–67. doi: 10.1080/07328303.2012.741637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Brennan PJ, Tatituri RV, Brigl M, et al. Invariant natural killer T cells recognize lipid self antigen induced by microbial danger signals. Nat. Immunol. 2011;12(12):1202–1211. doi: 10.1038/ni.2143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tatituri RV, Watts GF, Bhowruth V, et al. Recognition of microbial and mammalian phospholipid antigens by NKT cells with diverse TCRs. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2013;110(5):1827–1832. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1220601110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Amprey JL, Im JS, Turco SJ, et al. A subset of liver NK T cells is activated during Leishmania donovani infection by CD1d-bound lipophosphoglycan. J. Exp. Med. 2004;200(7):895–904. doi: 10.1084/jem.20040704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fischer K, Scotet E, Niemeyer M, et al. Mycobacterial phosphatidylinositol mannoside is a natural antigen for CD1d-restricted T cells. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101(29):10685–10690. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403787101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Godfrey DI, Rossjohn J. New ways to turn on NKT cells. J. Exp. Med. 2011;208(6):1121–1125. doi: 10.1084/jem.20110983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kinjo Y, Tupin E, Wu D, et al. Natural killer T cells recognize diacylglycerol antigens from pathogenic bacteria. Nat. Immunol. 2006;7(9):978–986. doi: 10.1038/ni1380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kawano T, Cui J, Koezuka Y, et al. CD1d-restricted and TCR-mediated activation of valpha14 NKT cells by glycosylceramides. Science. 1997;278(5343):1626–1629. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5343.1626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kobayashi E, Motoki K, Uchida T, Fukushima H, Koezuka Y. KRN7000, a novel immunomodulator, and its antitumor activities. Oncol. Res. 1995;7(10-11):529–534. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Im JS, Yu KO, Illarionov PA, et al. Direct measurement of antigen binding properties of CD1 proteins using fluorescent lipid probes. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279(1):299–310. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M308803200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sidobre S, Naidenko OV, Sim BC, Gascoigne NR, Garcia KC, Kronenberg M. The V alpha 14 NKT cell TCR exhibits high-affinity binding to a glycolipid/CD1d complex. J. Immunol. 2002;169(3):1340–1348. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.3.1340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60•.Im JS, Arora P, Bricard G, et al. Kinetics and cellular site of glycolipid loading control the outcome of natural killer T cell activation. Immunity. 2009;30(6):888–898. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.03.022. Highlights the importance of endosomal trafficking and lipid raft localization for controlling the quality of iNKT-cell responses to different forms of αGalCer.

- 61.Arora P, Venkataswamy MM, Baena A, et al. A rapid fluorescence-based assay for classification of iNKT cell activating glycolipids. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133(14):5198–5201. doi: 10.1021/ja200070u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Miyamoto K, Miyake S, Yamamura T. A synthetic glycolipid prevents autoimmune encephalomyelitis by inducing TH2 bias of natural killer T cells. Nature. 2001;413(6855):531–534. doi: 10.1038/35097097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yu KO, Im JS, Molano A, et al. Modulation of CD1d-restricted NKT cell responses by using N-acyl variants of alpha-galactosylceramides. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102(9):3383–3388. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407488102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Schmieg J, Yang G, Franck RW, Tsuji M. Superior protection against malaria and melanoma metastases by a C-glycoside analogue of the natural killer T cell ligand alpha-Galactosylceramide. J. Exp. Med. 2003;198(11):1631–1641. doi: 10.1084/jem.20031192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tashiro T, Sekine-Kondo E, Shigeura T, et al. Induction of Th1-biased cytokine production by alpha-carba-GalCer, a neoglycolipid ligand for NKT cells. Int. Immunol. 2010;22(4):319–328. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxq012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Padte NN, Li X, Tsuji M, Vasan S. Clinical development of a novel CD1d-binding NKT cell ligand as a vaccine adjuvant. Clin. Immunol. 2011;140(2):142–151. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2010.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67••.Li X, Fujio M, Imamura M, et al. Design of a potent CD1d-binding NKT cell ligand as a vaccine adjuvant. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107(29):13010–13015. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1006662107. Design of a potent αGalCer analog, 7DW8–5, and its use in mouse models of vaccination.

- 68.Oki S, Chiba A, Yamamura T, Miyake S. The clinical implication and molecular mechanism of preferential IL-4 production by modified glycolipid-stimulated NKT cells. J. Clin. Invest. 2004;113(11):1631–1640. doi: 10.1172/JCI20862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Mccarthy C, Shepherd D, Fleire S, et al. The length of lipids bound to human CD1d molecules modulates the affinity of NKT cell TCR and the threshold of NKT cell activation. J. Exp. Med. 2007;204(5):1131–1144. doi: 10.1084/jem.20062342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Forestier C, Takaki T, Molano A, et al. Improved outcomes in NOD mice treated with a novel Th2 cytokine-biasing NKT cell activator. J. Immunol. 2007;178(3):1415–1425. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.3.1415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Chang YJ, Huang JR, Tsai YC, et al. Potent immune-modulating and anticancer effects of NKT cell stimulatory glycolipids. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104(25):10299–10304. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0703824104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Patel O, Pellicci DG, Uldrich AP, et al. Vbeta2 natural killer T cell antigen receptor-mediated recognition of CD1d-glycolipid antigen. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108(47):19007–19012. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1109066108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Carreno LJ, Riquelme EM, Gonzalez PA, et al. T-cell antagonism by short half-life pMHC ligands can be mediated by an efficient trapping of T-cell polarization toward the APC. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107(1):210–215. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0911258107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Gonzalez PA, Carreno LJ, Coombs D, et al. T cell receptor binding kinetics required for T cell activation depend on the density of cognate ligand on the antigen-presenting cell. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102(13):4824–4829. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500922102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Lee YJ, Holzapfel KL, Zhu J, Jameson SC, Hogquist KA. Steady-state production of IL-4 modulates immunity in mouse strains and is determined by lineage diversity of iNKT cells. Nat. Immunol. 2013;14(11):1146–1154. doi: 10.1038/ni.2731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kang SJ, Cresswell P. Saposins facilitate CD1d-restricted presentation of an exogenous lipid antigen to T cells. Nat. Immunol. 2004;5(2):175–181. doi: 10.1038/ni1034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Yuan W, Qi X, Tsang P, et al. Saposin B is the dominant saposin that facilitates lipid binding to human CD1d molecules. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104(13):5551–5556. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700617104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Zhou D, Cantu C, 3rd, Sagiv Y, et al. Editing of CD1d-bound lipid antigens by endosomal lipid transfer proteins. Science. 2004;303(5657):523–527. doi: 10.1126/science.1092009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Fujii S, Shimizu K, Smith C, Bonifaz L, Steinman RM. Activation of natural killer T cells by alpha-galactosylceramide rapidly induces the full maturation of dendritic cells in vivo and thereby acts as an adjuvant for combined CD4 and CD8 T cell immunity to a coadministered protein. J. Exp. Med. 2003;198(2):267–279. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Stober D, Jomantaite I, Schirmbeck R, Reimann J. NKT cells provide help for dendritic cell-dependent priming of MHC class I-restricted CD8+ T cells in vivo. J. Immunol. 2003;170(5):2540–2548. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.5.2540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Kitamura H, Iwakabe K, Yahata T, et al. The natural killer T (NKT) cell ligand alpha-galactosylceramide demonstrates its immunopotentiating effect by inducing interleukin (IL)-12 production by dendritic cells and IL-12 receptor expression on NKT cells. J. Exp. Med. 1999;189(7):1121–1128. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.7.1121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82••.Venkataswamy MM, Baena A, Goldberg MF, et al. Incorporation of NKT cell-activating glycolipids enhances immunogenicity and vaccine efficacy of Mycobacterium bovis bacillus Calmette-Guerin. J. Immunol. 2009;183(3):1644–1656. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900858. Describes a method for direct incorporation of αGalCer into a live attenuated mycobacterial vaccine strain, and the impact of this on vaccine-induced CD8 T-cell responses.

- 83.Lisbonne M, Diem S, De Castro Keller A, et al. Cutting edge: invariant V alpha 14 NKT cells are required for allergen-induced airway inflammation and hyperreactivity in an experimental asthma model. J. Immunol. 2003;171(4):1637–1641. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.4.1637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kobrynski LJ, Sousa AO, Nahmias AJ, Lee FK. Cutting edge: antibody production to pneumococcal polysaccharides requires CD1 molecules and CD8+ T cells. J. Immunol. 2005;174(4):1787–1790. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.4.1787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Schofield L, Mcconville MJ, Hansen D, et al. CD1d-restricted immunoglobulin G formation to GPI-anchored antigens mediated by NKT cells. Science. 1999;283(5399):225–229. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5399.225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Singh N, Hong S, Scherer DC, et al. Cutting edge: activation of NK T cells by CD1d and alpha-galactosylceramide directs conventional T cells to the acquisition of a Th2 phenotype. J. Immunol. 1999;163(5):2373–2377. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Galli G, Pittoni P, Tonti E, et al. Invariant NKT cells sustain specific B cell responses and memory. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104(10):3984–3989. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700191104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Devera TS, Shah HB, Lang GA, Lang ML. Glycolipid-activated NKT cells support the induction of persistent plasma cell responses and antibody titers. Eur. J. Immunol. 2008;38(4):1001–1011. doi: 10.1002/eji.200738000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Galli G, Nuti S, Tavarini S, et al. CD1d-restricted help to B cells by human invariant natural killer T lymphocytes. J. Exp. Med. 2003;197(8):1051–1057. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Bai L, Deng S, Reboulet R, et al. Natural killer T (NKT)-B-cell interactions promote prolonged antibody responses and long-term memory to pneumococcal capsular polysaccharides. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2013;110(40):16097–16102. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1303218110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Lang GA, Devera TS, Lang ML. Requirement for CD1d expression by B cells to stimulate NKT cell-enhanced antibody production. Blood. 2008;111(4):2158–2162. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-10-117309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Gray JD, Horwitz DA. Activated human NK cells can stimulate resting B cells to secrete immunoglobulin. J. Immunol. 1995;154(11):5656–5664. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Gonzalez-Aseguinolaza G, Van Kaer L, Bergmann CC, et al. Natural killer T cell ligand alpha-galactosylceramide enhances protective immunity induced by malaria vaccines. J. Exp. Med. 2002;195(5):617–624. doi: 10.1084/jem.20011889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Ko SY, Ko HJ, Chang WS, Park SH, Kweon MN, Kang CY. alpha-Galactosylceramide can act as a nasal vaccine adjuvant inducing protective immune responses against viral infection and tumor. J. Immunol. 2005;175(5):3309–3317. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.5.3309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Kamijuku H, Nagata Y, Jiang X, et al. Mechanism of NKT cell activation by intranasal coadministration of alpha-galactosylceramide, which can induce cross-protection against influenza viruses. Mucosal Immunol. 2008;1(3):208–218. doi: 10.1038/mi.2008.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Youn HJ, Ko SY, Lee KA, et al. A single intranasal immunization with inactivated influenza virus and alpha-galactosylceramide induces long-term protective immunity without redirecting antigen to the central nervous system. Vaccine. 2007;25(28):5189–5198. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2007.04.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Kopecky-Bromberg SA, Fraser KA, Pica N, et al. Alpha-C-galactosylceramide as an adjuvant for a live attenuated influenza virus vaccine. Vaccine. 2009;27(28):3766–3774. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.03.090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Lee YS, Lee KA, Lee JY, et al. An alpha-GalCer analogue with branched acyl chain enhances protective immune responses in a nasal influenza vaccine. Vaccine. 2011;29(3):417–425. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Huang Y, Chen A, Li X, et al. Enhancement of HIV DNA vaccine immunogenicity by the NKT cell ligand, alpha-galactosylceramide. Vaccine. 2008;26(15):1807–1816. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Shibolet O, Alper R, Zlotogarov L, et al. NKT and CD8 lymphocytes mediate suppression of hepatocellular carcinoma growth via tumor antigen-pulsed dendritic cells. Int. J. Cancer. 2003;106(2):236–243. doi: 10.1002/ijc.11201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Chung Y, Qin H, Kang CY, Kim S, Kwak LW, Dong C. An NKT-mediated autologous vaccine generates CD4 T-cell dependent potent antilymphoma immunity. Blood. 2007;110(6):2013–2019. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-12-061309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Kim YJ, Ko HJ, Kim YS, et al. alpha-Galactosylceramide-loaded, antigen-expressing B cells prime a wide spectrum of antitumor immunity. Int. J. Cancer. 2008;122(12):2774–2783. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Kim D, Hung CF, Wu TC, Park YM. DNA vaccine with alpha-galactosylceramide at prime phase enhances anti-tumor immunity after boosting with antigen-expressing dendritic cells. Vaccine. 2010;28(45):7297–7305. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.08.079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Teng MW, Westwood JA, Darcy PK, et al. Combined natural killer T-cell based immunotherapy eradicates established tumors in mice. Cancer Res. 2007;67(15):7495–7504. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-0941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Giaccone G, Punt CJ, Ando Y, et al. A phase I study of the natural killer T-cell ligand alpha-galactosylceramide (KRN7000) in patients with solid tumors. Clin. Cancer Res. 2002;8(12):3702–3709. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Nieda M, Okai M, Tazbirkova A, et al. Therapeutic activation of Valpha24+Vbeta11 +NKT cells in human subjects results in highly coordinated secondary activation of acquired and innate immunity. Blood. 2004;103(2):383–389. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-04-1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Okai M, Nieda M, Tazbirkova A, et al. Human peripheral blood Valpha24+ Vbeta11+ NKT cells expand following administration of alpha-galactosylceramide-pulsed dendritic cells. Vox Sang. 2002;83(3):250–253. doi: 10.1046/j.1423-0410.2002.00217.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108•.Kunii N, Horiguchi S, Motohashi S, et al. Combination therapy of in vitro-expanded natural killer T cells and alpha-galactosylceramide-pulsed antigen-presenting cells in patients with recurrent head and neck carcinoma. Cancer Sci. 2009;100(6):1092–1098. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2009.01135.x. An early-phase human clinical trial showing potentially beneficial effects of NKT-cell activation on antitumoral immunity.

- 109.Richter J, Neparidze N, Zhang L, et al. Clinical regressions and broad immune activation following combination therapy targeting human NKT cells in myeloma. Blood. 2013;121(3):423–430. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-06-435503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Veldt BJ, Van Der Vliet HJ, Von Blomberg BM, et al. Randomized placebo controlled Phase I/II trial of alpha-galactosylceramide for the treatment of chronic hepatitis C. J. Hepatol. 2007;47(3):356–365. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2007.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Woltman AM, Ter Borg MJ, Binda RS, et al. Alpha-galactosylceramide in chronic hepatitis B infection: results from a randomized placebo-controlled Phase I/II trial. Antivir. Ther. 2009;14(6):809–818. doi: 10.3851/IMP1295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Sullivan BA, Kronenberg M. Activation or anergy: NKT cells are stunned by alpha-galactosylceramide. J. Clin. Invest. 2005;115(9):2328–2329. doi: 10.1172/JCI26297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Parekh VV, Wilson MT, Olivares-Villagomez D, et al. Glycolipid antigen induces long-term natural killer T cell anergy in mice. J. Clin. Invest. 2005;115(9):2572–2583. doi: 10.1172/JCI24762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Thapa P, Zhang G, Xia C, et al. Nanoparticle formulated alpha-galactosylceramide activates NKT cells without inducing anergy. Vaccine. 2009;27(25-26):3484–3488. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.01.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Leung B, Harris HW. NKT cells in sepsis. Clin. Dev. Immunol. 2010 doi: 10.1155/2010/414650. 2010. doi:10.1155/2010/414650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116••.Stirnemann K, Romero JF, Baldi L, et al. Sustained activation and tumor targeting of NKT cells using a CD1d-anti-HER2-scFv fusion protein induce antitumor effects in mice. J. Clin. Invest. 2008;118(3):994–1005. doi: 10.1172/JCI33249. Development of an approach for targeting NKT-cell activation to tumors using αGalCer-loaded tumor Ag-specific-antibody/CD1d fusion proteins in a mouse model of melanoma.