Abstract

Dilated cardiomyopathy is a serious and life-threatening disorder in children. It is the most common form of pediatric cardiomyopathy. Therapy for this condition has varied little over the last several decades and mortality continues to be high. Currently, children with dilated cardiomyopathy are treated with pharmacological agents and mechanical support, but most require heart transplantation and survival rates are not optimal. The lack of common treatment guidelines and inadequate survival rates after transplantation necessitates more therapeutic clinical trials. Stem cell and cell-based therapies offer an innovative approach to restore cardiac structure and function towards normal, possibly reducing the need for aggressive therapies and cardiac transplantation. Mesenchymal stem cells and cardiac stem cells may be the most promising cell types for treating children with dilated cardiomyopathy. The medical community must begin a systematic investigation of the benefits of current and novel treatments such as stem cell therapies for treating pediatric dilated cardiomyopathy.

Keywords: Pediatric dilated cardiomyopathy, Idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy, Pediatric congestive heart failure, Stem cells, Cell based therapy, Bone marrow stem cells, Mesenchymal stem cells, Cardiac stem cells

Introduction

Dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) is a rare, but morbid illness in children. It is a myocardial disorder characterized by left ventricular chamber enlargement and systolic dysfunction that often manifests as congestive heart failure [1, 2]. While DCM remains the most common form of pediatric cardiomyopathy, its underlying cause is in many cases unknown [3]. At present, the approach to treating children with DCM is much the same as the approach taken to treat adults. Pharmacological agents are used to limit symptoms, prevent sudden cardiac death, and delay heart failure, while heart transplantation remains the ultimate approach to treat heart failure caused by DCM [4, 5]. Given the cost of heart transplantation, the differential benefit children receive from transplant based on heart failure stage, and the exclusion of patients with other comorbities for transplant, other therapeutic options are needed to broaden the therapeutic armamentarium for pediatric DCM aimed at halting its progression to heart failure and improving patient outcome [4, 6]. In this regard stem cell and cell-based therapies offer a potentially new and innovative approach to restore cardiac structure and function towards normal, possibly reducing the need for cardiac transplantation or other aggressive therapies. In this review, the epidemiology of pediatric dilated cardiomyopathy as well as its current therapies and outcomes are first presented. Next, current research on stem cell treatment of cardiac disorders is explored. Lastly, the potential and challenges of stem cell therapies to treat pediatric DCM are discussed.

Epidemiology of Pediatric Cardiomyopathies

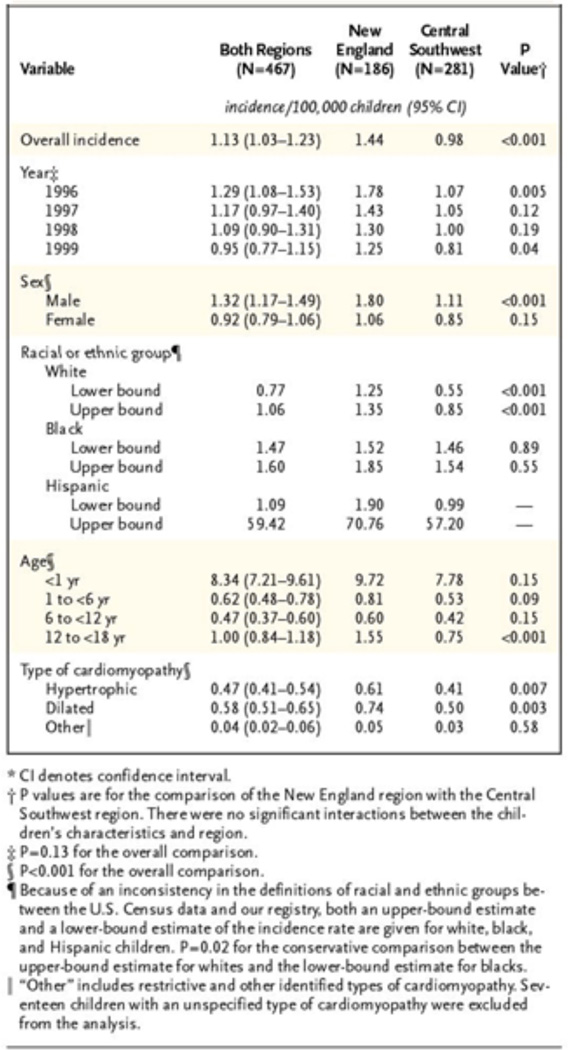

Cardiomyopathy in children is a very serious and often life-threatening disorder. Approximately 40 percent of children with symptomatic cardiomyopathy receive a heart transplant or die within the first two years, and despite medical advances, outcomes have not significantly improved [7]. The Pediatric Cardiomyopathy Registry (PCMR) found the overall annual incidence of cardiomyopathy in two regions of the United States, New England and Central Southwest, to be 1.13 cases per 100,000 children [8]. The study found differences in age, sex, and race associated with the incidence of cardiomyopathy. The incidence was significantly higher among infants younger than 1 year as compared to children and adolescents. The incidence was higher among boys than among girls, and higher among black children than among white children (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Annual Incidence of Pediatric Cardiomyopathy in New England and the Central Southwest on the Basis of Cases Diagnosed in 1996, 1997, 1998, and 1999. Lipshultz et al., 2003; Reference 8.

The incidence of cardiomyopathy also differs according to type. Dilated cardiomyopathy accounts for 51 percent of the cases, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy accounts for 42 percent, and restrictive and arrhythmic account for 3 percent. Among the leading causes of dilated cardiomyopathies, 39 percent were neuromuscular disorders and 27 percent were myocarditis. The primary cause of nearly 37 percent of children with dilated cardiomyopathy was unknown at diagnosis. Moreover, this study found that the median age at diagnosis for patients with dilated cardiomyopathy was 1.8 years. The mortality rate and heart transplantation rate two years after diagnosis were 13.6 percent and 12.7 percent, respectively [8].

The PCMR reports survival rates with freedom from death or re-transplantation after a diagnosis of pediatric dilated cardiomyopathy to be 69 percent at 1 year and 46 percent at 10 years [3]. In large part due to cardiac transplantation, the majority of children diagnosed with DCM are living longer and surviving into adulthood. Hence, DCM is becoming a chronic disease associated with high costs [9]. A cost-effectiveness study of pediatric heart transplantation was made to determine to determine the costs of pediatric heart transplantation [10]. Data from 95 pediatric patients undergoing transplantation at the University of Emory Medical Center from 1997 through 2004 were reviewed to determine the cost of transplantation, pre-transplant care, organ procurement, initial hospitalization, and follow-up care. The cost of primary pediatric heart transplantation relative to the benefit, expressed as quality-adjusted year of life (QALY) gained, was reported as $49,679 per QALY gained. This was within the accepted frame of a cost-effective therapy of $50,000 per QALY. However, the estimate for re-transplantation was $87,883 per QALY gained, and the sensitivity analysis identified the range from $70,834 to $103,661 per QALY gained. Overall, the study concludes that while primary pediatric heart transplantation is within the accepted range of cost effectiveness, re-transplantation has higher costs relative to benefits gained due to shorter graft survival [9, 10]

Treatment of pediatric dilated cardiomyopathy is complex and costly, and as is the goal of treating all illnesses, the goal of treating DCM should be to optimize both the cost-effectiveness ratio and child survival rate. In the following section, the current therapies for DCM and their outcomes are explored. This discussion introduces some of the barriers in treatment, and as such, encourages clinical research on traditional and potential cell based therapies for pediatric DCM.

Outcomes of Current Therapies

Pharmacological medical therapy fails within two years of diagnosis of idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy (IDC) in approximately 40 percent of children. These children either receive a heart transplant or die [7, 11]. Over the last several decades there has been little change in treatment strategy. Given the absence of evidence-based standards for IDC and heart failure (HF), clinical treatment strategies vary widely [11]. In a study by the PMCR that compared therapies for children with IDC between 1990 to 1995 and 2000 to 2005, approximately 73 percent of the children had symptomatic heart failure at diagnosis [11]. The study showed that anti-HF medications, defined as digoxin and/or diuretics, were the most commonly used medication at diagnosis across both periods. The administration of the anti-HF medications differed by functional class, whereby they were administered to 60 percent of asymptomatic, class I children and to 93 percent of ≥class 2 children [11]. The study also discussed that while digoxin should not be administered to children with class I HF because it has not been associated with increased survival in adult trials, approximately 60 percent of children with class I HF received this agent [11].

The second most used therapy was the angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor (ACEI), which was administered to 74 percent of children within the first year of diagnosis [11]. ACEI was more commonly administered in patients with a larger left ventricular dimension and lower fractional shortening, as well as to those children with the worst functional class of HF, class IV [11]. ACEI therapy is recommended for almost all children with symptomatic HF or asymptomatic left ventricular dysfunction (assuming no reaction to the drug), except in cases of clinical decompensation [12, 13]. In the same PMCR study, however, only about half (53 percent) of the children with asymptomatic left ventricular dysfunction, class I HF, received ACEI therapy [11].

The PMCR found that beta-adrenergic blockade medications were not widely used, following the recommendation not to use these medications in children with HF. Moreover, calcium channel blockers and pacemakers or automatic implanted cardiac defibrillators were typically not used in initial therapy. Finally, the study found that use of dietary modification, such as salt restriction or carnitine supplementation, was infrequent and varied among centers [11].

These findings indicate a wide variation in the practice of treating children with IDC and HF, primarily due to the lack of evidence based medicine. As such, the 1 year rate of death or transplantation for children with IDC is only 39 percent, and the 5 year rate, 53 percent [11]. The lack of common therapeutic guidelines as well as inadequate survival rates for pediatric IDC necessitates more therapeutic clinical trials. In conjunction with these trials, other therapies such as cell based therapy should be explored as new therapeutic avenues.

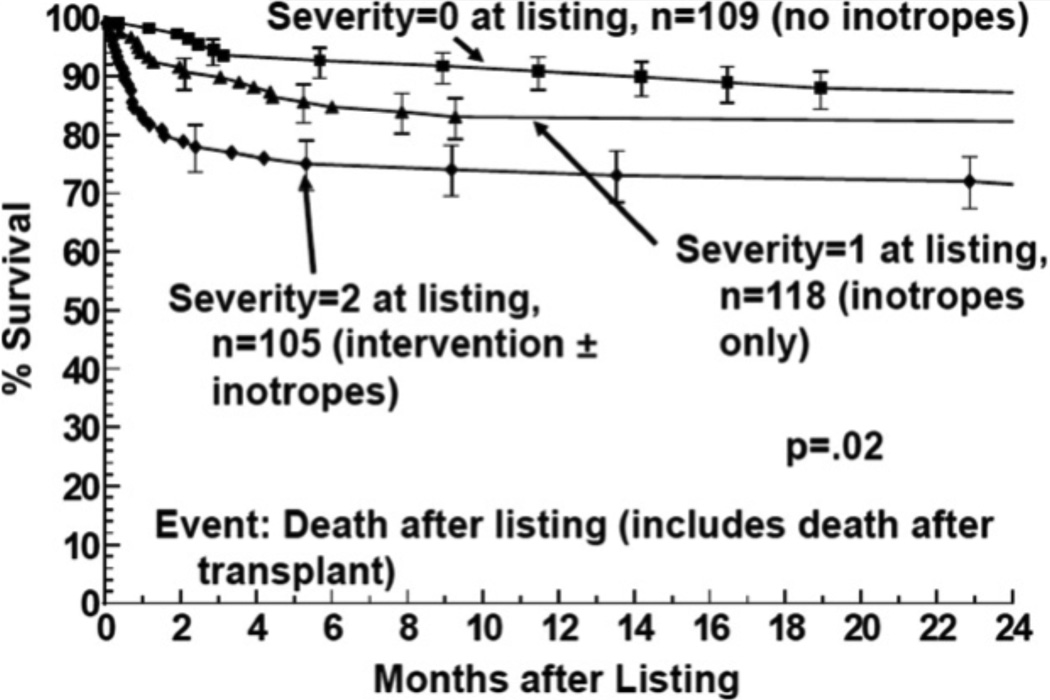

In another study, the PMCR assessed differences in mortality in children with different levels of heart failure severity before and after transplant [6]. After observing 332 children, 12-month mortality after listing was 9% for those children not on inotropes, 16% for those on inotropes, and 26% for those on mechanical ventilatory and/or circulatory support (Figure 2). They noted that almost all children that were on inotropes and/or mechanical ventilatory or circulatory support died within the first 6 months before transplant or after transplant. Mortality after listing for those children on mechanical ventilator and/or circulatory support occurred while waiting for an allograft, while mortality for those on inotropes was equally distributed between mortality before and after transplant. Mortality in those children who were not on intotropic medication reflected mortality after transplant [6]. This study concluded that pediatric cardiomyopathy patients who require inotropic therapy and mechanical ventilatory and/or circulatory support receive the most benefit from heart transplantation.

Figure 2.

Survival after listing for heart transplantation among children with cardiomyopathy by heart failure severity score: 2 = children on mechanical ventilatory or circulatory support; 1 = children on intravenous inotropic support without mechanical support; 0 = children on neither intravenous inotropic or mechanical support. Larsen et al., 2011; Reference 6

While heart transplantation is indicated for those children with advanced heart failure and on mechanical support, this leaves a great number of children that simply depend on pharmacological agents for treatment and survival. The differential benefit that children with HF receive from transplant based on heart failure stage is an opportunity to explore other therapies like stem cell therapy for those children with a lower severity of HF. Doing so may improve their condition and thwart the need for heart transplantation. As previously stated, pediatric clinical trials on medication therapy and cell based therapy must be a priority in order to formulate evidence-based guideline for treating children with cardiomyopathy.

The incidence of sudden cardiac death (SCD) in children in the USA with DCM was unknown until Lipshultz and colleagues studied a cohort of 1,803 children in the PCMR with a diagnosis of DCM from 1990 to 2009 [14]. The purpose of their study was to determine the incidence and risk factors associated with SCD in children with DCM as a means to better evaluate who may benefit most from implantable cardioverter-defibrillators. They estimated the 5 year cumulative incidence rates of SCD to be 2.4 percent, of non-SCD to be 12.1 percent, and of heart transplantation to be 29 percent. Patient sex, race/ethnicity, family history, cause of DCM, and LV fractional shortening were not independent risk factors associated with SCD. They determined, however, that LV end-systolic dimension z-score of >2.6 at an age of diagnosis younger than 14.3 years and a LV posterior wall thickness to end-diastolic dimension ratio of <0.14 were associated with SCD. They also noted that patients receiving anti-arrhythmic medications were at a higher risk of SCD [14]. What is important to take from these finding is that children require meticulous screening in order to be considered for implantable cardioverter-defibrillator placement.

In contrast with adults, SCD is rare in children with DCM and death is typically caused by chronic heart failure [15]. There are pathophysiological differences that may account for the lower incidence of SCD in children, but these will not be discussed here. Given this observation, innovative therapies such as stem cell therapy may be warranted in preventing pump failure and subsequent death. First, the medical community must begin a systematic investigation of the benefits of current treatments and novel treatments such as cell-based therapies for treating pediatric dilated cardiomyopathy. In the following section, the research on the potential of stem cells as a novel therapeutic agent to treat DCM is presented and discussed.

Clinical Trials

Over a decade ago, the concept of regenerating the heart was viewed as an impossibility. Today, there is great enthusiasm for the use of stem cells as regenerative therapy. Stem cells promote cardiac regeneration by potentially replacing diseased tissue, enhancing endogenous cellular repair, and improving cardiac function [5]. There is much optimism that this novel approach will eventually lead to effective clinical therapy for cardiac congenital abnormalities, ischemic injuries, and cardiomyopathies [5, 16].

Adult Stem Cells

The discovery that adult stem cells have the capacity to trans-differentiate into lineages other than the tissue of their origin promises wonderful therapeutic potential. Adult stem cells reside in and may be isolated from diverse sources such as bone marrow (BM), peripheral blood, fat, umbilical cord, or even testis in order to be used for repair of damaged organs. While early studies have been completed employing resident cardiac stem cells (CSCs) and offer major promise for repair of dysfunctional hearts [17], there is a larger database of trials testing BM-derived mononuclear cells (BMMNCs) and mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) for heart disease [18]. The vast majority of these trials are conducted in adults and thus the impact in children must be inferred and must be rigorously tested in future trials.

Bone Marrow Stem Cells

Whole BM and BMMNCs are the most widely studied type of cell for cellular cardiomyoplasty due to its well-defined stem cell compartments and easy accessibility. BMMNCs can be fractionated to hematopoietic (HSCs) or non-hematopoietic stem cells [19]. The role of several subtypes of non-hematopoietic stem cells in cardiac repair have been investigated: side population (SPs) [20], endothelial progenitor cells (EPCs) [21], mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) [22], multipotent adult progenitor cells (MAPCs) [23], multilineage inducible (MIAMI) cells [24] and very small embryonic like (VSEL), stem cells [25]. Since there has been extensive investigation of the therapeutic potential of BMMNCs and MSCs, these two types of cell-based therapies will be the focus of the following sections.

BM-Derived Mononuclear Cells (BMMNCs)

BMMNCs have undergone various experimental and clinical studies involving their transplantation and their mobilization to sites of cardiac injury in an effort to assess therapeutic potential. Trials with BM cells and their derivatives provide evidence that they are both safe and provide efficacy in treatment of cardiac disease [19]. While most studies have tested BMMNCs in the setting of patients with acute myocardial infarction, some have employed BMMNCs in the setting of patients with LV dysfunction and/or heart failure due to ischemic or non-ischemic causes [19].

In a meta-analysis evaluating data from 50 trials and 2625 patients [26], BM cell-based therapies were found to provide improvements in cardiac function by improving left ventricular ejection fraction, reducing left ventricular end-systolic and end-diastolic volume, and reducing infarct size. These results were noted in both acute myocardial infarction and chronic ischemic heart disease studies, and persisted during long-term follow up. Importantly, BM cell transplantation reduced mortality, stent thrombosis, and recurrent myocardial infarction in patients with ischemic heart disease [26]. While these studies offer promising results, the data must continue to be assessed in an effort to determine long-term benefit of stem cell transplantation.

The REPAIR-AMI study focused on the therapeutic benefits of BMMNCs in the context of acute myocardial infarction (MI) [27]. In this study, 204 patients with acute underwent successful reperfusion of the occluded coronary vessel(s), and 3–7 days later were randomized to receive intracoronary infusion of autologous BMMNCs or placebo. The DSMB data reveals that by four months, patients who received the stem cells had a significantly improved left ventricular ejection fraction. Moreover, 1-year follow-up data show that the BMMNC-treated patients had an improved event-free survival (death, recurrence of MI, revascularization, or rehospitalization for heart failure) as compared to the placebo [27, Table 1]. The Cardiovascular Cell Therapy Research Network (CCTRN) recently investigated the benefits and timing of BMMNCs delivery following acute myocardial infarction [28, 29]. The TIME-CCTRN randomized trial enrolled 120 patients to investigate the administration of BMMNCs at either 3 days or 7 days after an acute MI and concluded that there was no significant effect on global or regional left ventricular function compared to the control group [28, 29, Table 1]. The LateTIME-CCTRN randomized trial was the first to determine the temporal effect of autologous BMMNCs administration 2 to 3 weeks post-MI. This study also concluded that intracoronary infusion of autologous BMMNCs weeks later had no significant effect on left ventricular function [28, 29, Table 1]. Given that there have been conflicting findings among studies with BMMNCs, other stem cells such as MSCs and CSCs warrant further investigation as to their potential therapeutic effects.

Table 1.

Summary of Stem Cell Clinical Trials.

| Study | Design | Objectives | Endpoints | Findings | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The REPAIR-AMI Trial | Phase III, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial Enrollment: 204 patients |

To determine the efficacy of infusing BMMCs into the infarct vessel (after successful reperfusion therapy) in improving ventricular contractile function. |

Primary Endpoint: Change in global left ventricular function in quantitative LV angiography Secondary Endpoints: Several including improvement of regional wall motion in infarct area, reduction of LVESV, major adverse cardiac events, etc. |

Intracoronary administration of BMMCs improved recovery of left ventricular contractile function in patients with acute MI. |

1 yr. follow-up revealed BMMC-treated patients had improved event-free survival as compared to the placebo; further large scale studies are warranted to determine effect of BMMC treatment on morbidity and mortality. |

|

The TIME Randomized Trial |

Randomized, 2×2 factorial, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial Enrollment: 120 patients |

To determine the effect of intracoronary autologous BMMC delivery after STEMI on recovery of global and regional LV function; to determine whether timing of BMMC delivery, 3 days vs. 7 days after reperfusion, influences the effect. |

Primary Endpoints: Change in global (LVEF) and regional (wall motion) LV function in infarct and border zones at 6 months Secondary Endpoints: Major adverse cardiovascular events, changes in LV volumes, and infarct size |

No significant effect on recovery of global or regional LV function compared with placebo after administration of intracoronary BMMCs at either 3 days or 7 days after the event. |

While the TIME and LateTIME trials both did not find BMMCs effective in improving LV function post-STEMI, long-term follow-up and new composite endpoints may be warranted to determine whether there is a role for BMMCs after AMI. |

|

The LateTIME Randomized Trial |

Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial Enrollment: 87 patients |

To determine the effect of intracoronary delivery of autologous BMMCs on global and regional LV function when delivered 2 to 3 weeks after first AMI. |

Primary Endpoints: Changes in global LVEF and regional (wall motion) LV function in the infarct and border zone at 6 months Secondary Endpoints: Changes in LV volumes and infarct size |

Intracoronary infusion of autologous BMMCs vs. placebo infusion, 2 to 3 weeks after PCI, did not improve global or regional function at 6 months. |

|

| FOCUS-HF | Phase I, randomized, single-blind study Enrollment: 30 patients |

To determine the safety and efficacy of the transendocardial delivery of ABMMNCs in no-option patients with chronic HF. |

Primary Endpoint: Safety: SAEs Secondary Endpoint: Efficacy: MVO2, SPECT, and 2-dimensional echocardiography, and QOL assessment |

ABMMNC therapy is safe. It improves symptoms, QOL, and possibly perfusion in patients with chronic HF. |

The small sample size must betaken into account when considering the findings on safety and efficacy. |

| The FOCUS-CCTRN trial | Phase II, randomized double-blind, placebo-controlled trial Enrollment: 153 patients |

To determine the effect of administration of BMMCs through transendocardial injections on LVESV, or MVO2in patients with CAD or LV dysfunction, and limiting HF or angina. |

Primary Endpoints: Changes in LVESV, maximal oxygen consumption, and, reversibility on SPECT |

Transendocardial injection of autologous BMMCs (compared with placebo) did not improve LVESV, MVO2 or reversibility on SPECT. |

|

| The FOCUS Study | Phase II, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial Estimated Enrollment: 92 patients |

To determine the safety and efficacy of intramyocardial injection of autologous BMMCs under electromechanical guidance for patients with chronic ischemic heart disease and LV dysfunction. |

Primary Endpoints: Change in maximal oxygen consumption, LV end systolic volume (LVESV), and in reversible defect size Secondary Endpoints: Regional wall motion, regional blood flow improvement, regional wall motion, and clinical improvements, including change in anginal score, incidence of a major adverse cardiac event, and reduction in fixed perfusion defect(s) |

Pending | Results from this study may help clarify the discrepancy between findings from the FOCUS-HF and FOCUS-CCTRN trials. |

| NOGA-DCM | Phase II, randomized, single-blind, placebo-controlled trial Estimated Enrollment: 60 patients |

To determine the safety and efficacy of intramyocardial stem cell therapy in patients with non-ischemic dilated cardiomyopathy; to compare clinical effects of intracoronary and intramyocardial stem cell delivery. |

Primary Endpoints: Changes in LV ejection fraction and dimensions Secondary Endpoints: Changes in exercise capacity, and changes in NT-proBNP levels |

Pending | Studies such as these will help elucidate the role of stem cells in treating DCM. |

|

Progenitor Cell Therapy in Dilative Cardiomyopathy |

Phase I/II, randomized, open label trial Estimated Enrollment: 30 patients |

To determine the effect of transplanting bone marrow-derived progenitor cells on recovery of LV function in patients with non- ischemic dilatative cardiomyopathy. |

Primary Endpoints: LV function (EF at 3 months) |

Pending | |

|

Study of Intravenous Adult Human Mesenchymal Stem Cells after Acute Myocardial Infarction |

Phase I, randomized, double blind, placebo controlled, dose escalating trial Enrollment: 53 patients |

To determine the safety and efficacy of intravenous allogeneic MSCs in patients with AMI. |

Primary Endpoints: Safety: TE-SAEs within 6 months Efficacy: LV volumes and EF |

Intravenous allogeneic MSC treatment is safe in patients with AMI. Findings show provisional efficacy. |

|

|

The POSEIDON randomized trial |

Phase I/II, randomized, open label comparison of allogeneic and autologous MSCs Enrollment: 30 patients |

To determine whether allogeneic MSCs are as safe and effective as autologous MSCs in patients with LV dysfunction due to ICM. |

Primary Endpoints: Safety: 30 day post catheterization incidence of predefined TE-SAEs Efficacy: 6-minute walk test, exercise peak VO2 MLHFQ, NYHAC, LV volumes, EF, early enhancement defect (EED; infarct size), and sphericity index |

Low rates of TE-SAEs. In aggregate, MSC injection favorably affected patient functional capacity, quality of life, and ventricular remodeling. |

Allogeneic MSCs have been found to be beneficial in treating ICM and should be explored for treating DCM. A larger number of patients must be studied in following trials. |

|

The POSEIDON-DCM Study |

Phase I/II, randomized, open label, pilot study Estimated Enrollment: 36 patients |

To comparative the safety and efficacy of transendocardial injection of autologous MSCs vs. allogeneic MSCs in patients with non-ischemic dilated cardiomyopathy. |

Primary Endpoints: Incidence of anyTE-SAEs Secondary Endpoints: Changes in regional LV function |

Pending | This study will help elucidate the role of MSCs in treating DCM. A larger number of patients is warranted in future trials. |

|

Intramuscular Injection of MSCs for Treatment of Children with Idiopathic Dilated Cardiomyopathy |

Phase I/II, randomized, open label trial Estimated Enrollment: 30 patients |

To determine the effects of intramuscular injection of umbilical cord MSCs on the ventricular function of children with IDCM. |

Primary Endpoints: Echocardiography Secondary Endpoints: 24h HOLTER, level of serum BNP,TNI,HGF, LIF and G/M-CSF; the expression level of c-kit,CD31,CD133 on peripheral blood mononuclear cells |

Pending | This is the first pediatric trial investigating the role of umbilical cord MSCs in treating IDCM. It will provide insight on the role of MSCs in treating IDCM. |

| MAGIC | Randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind study Enrollment: 97 patients |

To determine the safety and efficacy of skeletal myoblast transplantation in patients with LV dysfunction, MI, and indication for coronary surgery. |

Primary Endpoints: Efficacy: Changes in global and regional LV function at 6 months Safety: A composite index of major cardiac adverse events and ventricular arrhythmias |

Myoblast injections combined with coronary surgery in patients with depressed LV function did not improve echocardiographic heart function. |

In this trial, there was an increase in number of early postoperative arrhythmic events after myoblast transplantation. Skeletal myoblasts have had minimal success in treating ICM. |

| CADUCEUS | Phase I, randomized, open label trial Estimated Enrollment: 31 |

To determine the safety and efficacy of intracoronary delivery of cardiosphere-derived stem cells in patients with ischemic LV dysfunction and a recent myocardial infarction. |

Primary Endpoints: Proportion of patients who died due to v-tach, v-fib, or sudden unexpected death at 6 months, or had MI after cell infusion, new cardiac tumor formation on MRI, or a major adverse cardiac event. |

Pending | Findings from this study will help assess the role of CSCs in treating MI. They should be considered for treating DCM. |

ABMMNC, Autologous Bone Marrow Mononuclear Cell; BMMC, Bone Marrow Mononuclear Cell; CAD, Coronary Artery Disease; DCM, Dilated Cardiomyopathy; EF, Ejection Fraction; IDCM, Idiopathic Dilated Cardiomyopathy; HF, Heart Failure; ICM, Ischemic Cardiomyopathy; LV, Left Ventricular; LVEF, Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction; LVESV, Left Ventricular End-Systolic Volume; MVO2, Maximal Oxygen Consumption; NYHAC, New York Heart Association Class; QOL, Quality of Life; MI, Myocardial Infarction; MLHFQ, Minnesota Living with Heart Failure Questionnaire; MSC, Mesenchymal Stem Cell; SAE, Serious Adverse Event; SPECT, Single Photon Emission Computed Tomography; STEMI, ST-Elevated Myocardial Infarction; TE-SAE, Treatment-Emergent Serious Adverse Events

Event Free Survival: death, recurrence of MI, revascularization, or rehospitalization for heart failure

To date, there have been no completed trials investigating the potential therapeutic use of BMMNCs for treating pediatric cardiomyopathies but only case reports. The largest case series reported 9 pediatric heart failure patients who were compassionately treated with intracoronary delivery of autologous BMMNCs [30]. Very importantly, there were no procedure related serious complications in this series. One patient on extra corporeal membrane oxygenation had a catastrophic intracranial hemorrhage that eventually died, unrelated to treatment. Three patients had no improvement and subsequently underwent heart transplantation. The remaining five patients had regained clinical recovery by increasing their New York Heart Association classification by at least one classification level, decreased levels of brain natureitic peptide serum levels, and finally improved ejection function. By examining the etiologies of the heart failure in this series, a total of 6 DCM patients were treated but only three patients dramatically improved to the extent of not requiring heart transplantation. These results are initially promising to support a cell based therapy in DCM patients, but a more extensive trial will be needed to determine the efficacy and safety of this treatment.

All clinical trials have been performed on adults with cardiomyopathies and consequent heart failure. Moreover, ischemic cardiomyopathy and heart failure have been the focus of investigations. Most studies found that treating ischemic heart disease and heart failure with autologous BMMNCs was safe and suggested efficacy. A clinical trial by Perin et al. found that injection of bone marrow–derived stem cells in ischemic heart failure patients had potential for improving myocardial blood flow and enhancing left ventricular function [31]. The FOCUS-HF trial concluded that injection of autologous BMMNCs in patients with chronic heart failure is safe and improves symptoms, quality of life, and possibly perfusion [32, Table 1]. A more recent study, the FOCUS-CCTRN Trial, found contradictory evidence that injection of autologous BMMNCs compared with placebo did not improve left ventricular end systolic volume or other parameters like maximum oxygen consumption [33, Table 1]. The discrepancy among trials simply acknowledges a need for well-designed, large-scale studies of clinical therapeutic trials. Currently, the FOCUS Study is investigating the effectiveness of BMMNCs treatment for adults with ischemic cardiomyopathy [34, Table 1]. Studies like these and others to come will provide more evidence on the efficacy of BMMNCs for treating ischemic cardiomyopathy and heart failure.

There is currently ever-growing attention on using BM stem cells to treat dilated cardiomyopathy. While there is no data from trials published to date, studies such as NOGA-DCM is investigating the safety and efficacy of BM CD34+ cell injection in adult patients with non-ischemic dilated cardiomyopathy [35, Table 1]. Another study entitled Progenitor Cell Therapy in Dilative Cardiomyopathy is also investigating BM cell injection to assess its therapeutic potential in adults with dilated cardiomyopathy and heart failure [36, Table 1]. To date, there is only a brief report on the effect of autologous BMMNCs intramyocardial administration on a 3 month and 2 week old female child with dilated cardiomyopathy in Riga, Latvia [37]. The main finding was that left ventricular ejection fraction increased from 20% to 41% after stem cell transplantation at 4 months follow-up. Based on the totality of evidence, BM stem cell therapy warrants further investigation as to their therapeutic potential in treating both ischemic and non-ischemic dilated cardiomyopathy.

Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs)

MSCs, like other adult stem cells, have the capacity to self-replicate and differentiate into various tissue lineages, and as such, have been employed in regenerative therapies for cardiac disorders. They may be isolated from a variety of tissues such as BM, adipose, and umbilical cord, but it is not clear whether these all share the same cardiopoietic and immunomodulatory properties [19]. MSCs are unique immunologically as they have reduced expression of MHC class-I molecule, and lack of MHC class-II and co-stimulatory molecules CD80(B7-1), CD86(B7-2), and CD40 [19]. These stem cells are immunopriveleged and have been tested in phase I double-blind randomized clinical trials as an allogeneic graft [38].

As with BMMNCs, MSCs have been more stringently investigated for the treatment of acute myocardial infarctions. In a phase I double-blind placebo controlled clinical study of allogeneic MSCs, 53-patient were administered MSCs or placebo within 10 days after acute MI [38,Table1]. While this study was primarily designed to test safety, it also supported an improved outcome in the cell-treated patients, including a reduction in malignant ventricular arrhythmias, improved pulmonary function, improved ejection fraction in the subset of patients with anterior MI, and an improved patient well-being score at 6 months [38]. Recently, the results of the POSEIDON trial, a phase I/II randomized comparison of allogeneic and autologous MSCs in 30 patients with idiopathic cardiomyopathy, showed that allogeneic MSCs did not stimulate significant alloimmune reactions. Moreover, both autologous and allogeneic MSCs injections reduced infarct size by approximately 33% and promoted patient quality of life [39, Table 1]. There may be wider use of MSCs for cardiac repair as compared to other stem cells given that allogeneic MSCs have not been rejected by patients.

There is currently less data on the therapeutic potential of MSCs on patients with DCM. A study using a rat model of DCM showed that intramyocardial injection of MSCs resulted in improved myocardial perfusion and function, and decreased fibrosis [40]. A single case report published in 2010 demonstrated that intracoronary administration of autologous MSCs in an 11 year old boy with DCM and class IV HF was safe and had improved the boy’s clinical condition [41]. After MSC injection, the patient’s functional class changed from IV to III and II, the paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea disappeared, his appetite improved, he could walk and climb up two floor, and the need for hospitalization was reduced [41]. While cases like these stir enthusiasm, there is a need for well-designed, large-scale studies to assess the efficacy of MSCs in treating DCM.

Currently, the POSEIDON-DCM study conducted at the University of Miami is investigating the safety and efficacy of a transendocardial injection of autologous mesenchymal stem cells versus allogeneic mesenchymal stem cells in patients with non-ischemic DCM [42, Table 1]. There is also a pediatric clinical trial being conducted in China that is investigating the effect on intramuscular injection of umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells on ventricular function of children with idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy (IDCM) [43, Table 1]. Clinical trials such as these will provide insight on the potential therapeutic role of MSCs for treating patients with DCM. More research must be conducted in this field to replicate the safety and efficacy of MSCs in hopes that this cell-based therapy may serve as alternative to heart transplantation for treating DCM.

Skeletal Myoblasts

Skeletal myoblasts were the first cell type used as cell-based therapy in an effort to repair damaged myocardium and restore cardiac function [44]. These cells are derived from skeletal muscle and have the capacity to differentiate into muscle fiber [5]. There have been two large phase I/II clinical trials, the MAGIC study, assessing the efficacy of transplanted skeletal myoblast in patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy [45, 46]. The study showed that while there was dose-dependent attenuation in LV remodeling, there was no improvements in cardiac function [45, 46, Table 1]. Another unsettling problem with the use of skeletal myoblast for cell-based therapy is their association with arrhythmias [45, 46]. Myoblasts’ inability to improve cardiac function in humans may be attributed to the observed dysfunctional electrical coupling with resident cardiomyocytes as well as inability to transdifferentiate into cardiomyocytes in vivo [47]. Studies are now focusing on finding and characterizing skeletal muscle-derived cell population that are cardiogenic and that may improve cardiac repair [19, 48].

Cardiac Stem Cells (CSCs)

CSCs are adult stem cells that reside within the heart. They were first reported in 2002 by Hierlihy et al. (2002). The group demonstrated that the post-natal murine myocardium contains a side population of cells (SP cells) with stem cell-like activity that expressed the ATP-binding cassette transporter Abcg2 [49]. These cells were about 1% of total cardiac cells and were shown to differentiate into cardiomyocytes in vitro. Later in 2003, two groups, Beltrami et al. [50] and Oh et al. [51, 52], isolated and characterized novel CSCs from the murine heart. These stem cells are recognized according to the expression of three cell-surface markers: C-kit (the stem cell factor (SCF) receptor), MDR-1 (multidrug resistance protein-1), and/or Sca-1 (stem cell antigen-1). Like other adult stem cells, CSCs are self-renewing, clonogenic, and multipotent. Their ability to differentiate both in vitro and in vivo into cardiomyocytes, endothelial cells, and vascular smooth muscle has wonderful implications for repairing the damaged heart

C-kit+ CSCs are a candidate for cellular therapeutics. They have been isolated from and described in several species such as rodent, canine, porcine, and human. Moreover, their efficacy in treating cardiac disorders is being explored as they have been transplanted into the infarcted myocardium and shown multilineage differentiation and replacement of necrotic tissue with functional myocardium. Generally, these have been shown to promote cardiac function after ischemic reperfusion injury by limiting infarct size and reducing ventricular remodeling [50, 53]. Based on promising results from experimental evidence, C-kit+ CSCs are the first cardiac-specific stem cell population to be approved for human testing in a phase I clinical trial. The SCIPIO study aims to assess whether CSCs can regenerate myocardium and improve in contractile function in patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy [17].

Interestingly, Hatzistergos et al. (2010) showed that there is interaction between administered MSCs and endogenous CSCs, in which MSCs were shown to stimulate the proliferation of endogenous C-kit+ CSCs [54, 55]. After injecting post-MI female swine with GFP-labeled allogeneic MSCs, histological examination revealed chimeric clusters of cells containing adult cardiomyocytes, GFP+ MSCs, and c-kit+ CSC. The cells expressed connexin 43 gap junctions and N-cadherin connections between cells. Additionally, MSC-treated animals showed a 20-fold increase in C-kit+ CSCs [54, 55]. This finding warrants further investigation about the potential therapeutic role of MSCs and CSCs, alone or in combination, in the treatment of heart disease. Overall, further well-designed, large-scale trials are necessary to better assess the role of CSCs in regenerating the damaged heart. More evidence is needed to determine whether CSCs is a probable and useful treatment in disorders like cardiac ischemic injury, cardiomyopathies, and heart failure.

Another resident CSC is the suspended cardiospheres which is composed of a heterogenous mixture of stem cells and supporting cells [56, 57]. These cardiosphere derived cells have the ability to stimulate cardiac regeneration in animal models of infarction [58]. Recently, these results led to an initiation of a Phase I clinical trial, the CADUCEUS trial, involving cardiosphere derived cells obtained from right ventricle biopsies of adult myocardial ischemic patients [45, 59, Table 1]. There were no serious side effects reported and a reduction in myocardial scar mass following cell treatment was observed, but this finding did not correlate with improvement in left ventricle ejection function. Even though promising improvements in this Phase I study were seen, a larger more powered study will be needed to demonstrate the overall efficacy of this cell based therapy.

The only studies examining the biology of the resident CSCs in pediatric patients were recently reported [60, 61]. In these studies, C-kit+ CSCs were most prevalent and proliferative in the neonatal hearts but then steadily decreased with advancing age. The isolated cardiospheres from these pediatric patients were highly regenerative when tested in animal models of infarction. More importantly, neonatal derived cardiosphere derived cells were more regenerative when directly compared to adult derived cardiosphere derived cells, which was partly due to higher secreted angiogenic factors from the neonatal derived cells. These studies suggest that pediatric patients may have CSCs that have a strong regenerative ability which may rescue the myocardial function even better than what is currently seen in the adult stem cell trials.

The Challenges of Stem Cell Therapy

A challenge that stem cell therapy presents is their potential immunologic cellular rejection. Only MSCs have been demonstrated to be immunopriveleged and as such, allogeneic MSCs may have a wider accessibility to treat cardiac disorders [36]. Given safety, feasibility, and efficacy of the used of autologous adult stem cell therapy, the same parameters should be assessed of other allogeneic stem cells.

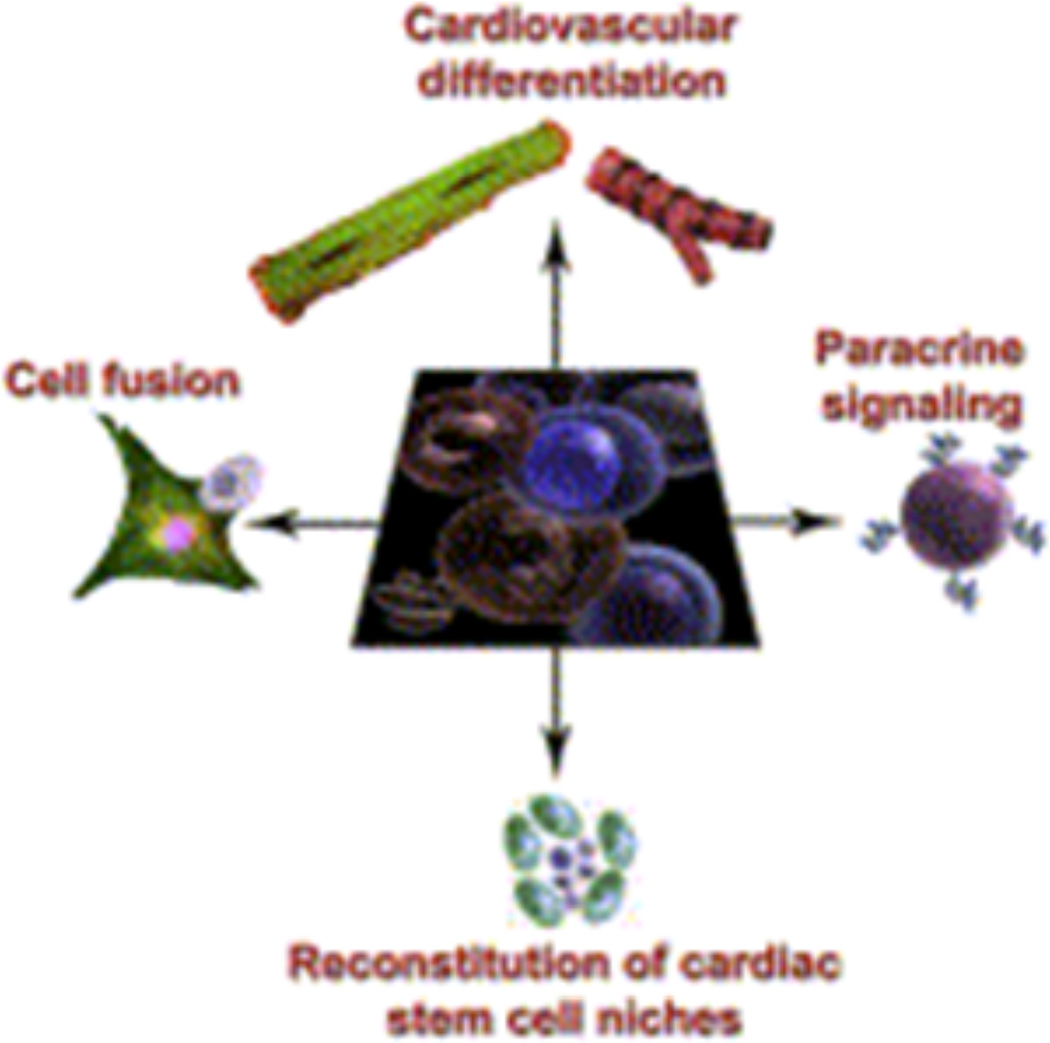

Another property of stem cell treatment that must be characterized is their mechanism of regenerating tissue. Do these cells differentiate in vivo and integrate into the electromechanical syncytial circuitry controlled by neuronal pacing? Do they fuse with native cardiomyocytes? Do they act by paracrine signaling and release cytokines that promote the survival of neighboring cells? Do these cells stimulate endogenous cardiac stem cells to initiate and/or maintain the healing process? Or is it a combination of these mechanisms (Figure 3)? Answering these questions has important implications for using specific stem cells for the treatment of particular cardiac diseases.

Figure 3.

Mechanisms of cardiac repair. Certain cells have the capacity for trilineage differentiation into cardiac myocytes, endothelial cells, and vascular smooth muscle cells. Fusion with adjoining host cells, paracrine signaling, and mobilization of endogenous stem cells are also critical and stimulate mechanisms for survival and proliferation of the host cells. Selem et al. 2011; Reference 19.

A fundamental challenge facing stem cell therapy is selection of the particular cell type for treatment of specific cardiac disorders. Given that mechanisms of myocardial damage are different, it is imperative that stem cells be characterized in terms of biological properties, mechanism of tissue repair, as well as practical purposes such as ease of procurement without ethical concerns. This review emphasizes particular adult stem cells-BMMNCs, MSCs, myoblasts, and CSCs-for the treatment of cardiac disorders like dilated cardiomyopathy because to date, these cells have been best characterized and have entered human clinical trials in order to assess their role in cardiac repair of certain diseases. There are also less obvious ethical qualms with the use of adult stem cells as compared to embryonic stem cells. As compared to embryonic stem cells, the aforementioned adult stem cells have not been shown to form teratomas [5].

Conclusions

Pediatric dilated cardiomyopathy is a serious disorder that can result in heart failure and death. Current therapies either delay the progression of DCM to heart failure or require a heart transplantation to replace the diseased heart. Heart transplantation, however, is costly and only provides a differential benefit to children with the worst stage of heart failure. Stem cell therapy may be a reasonable approach to treating pediatric heart failure by facilitating cardiac regeneration and improving cardiac function. While challenges to cell based therapy certainly exist, the scientific community should continue to investigate its therapeutic potential using multicenter controlled clinical trials. Stem cell therapy alone or in combination with other therapies may serve as a therapeutic alternative to heart transplantation and may treat the damaged heart.

References

- 1.Richardson P, McKenna W, Bristow M, et al. Report of the 1995 world health Organization/International society and federation of cardiology task force on the definition and classification of cardiomyopathies. Circulation. 1996;93(5):841–842. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.93.5.841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maron BJ, Towbin JA, Thiene G, et al. Contemporary definitions and classification of the cardiomyopathies. Circulation. 2006;113(14):1807–1816. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.174287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Towbin JA, Lowe AM, Colan SD, et al. Incidence, causes, and outcomes of dilated cardiomyopathy in children. JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association. 2006;296(15):1867–1876. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.15.1867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bernstein HS, Srivastava D. Stem cell therapy for cardiac disease. Pediatr Res. 2012;71(4-2):491–499. doi: 10.1038/pr.2011.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kaushal S, Jacobs JP, Gossett JG, et al. Innovation in basic science: Stem cells and their role in the treatment of paediatric cardiac failure − opportunities and challenges. Cardiol Young. 2009;19(Supplement S2):74. doi: 10.1017/S104795110999165X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Larsen RL, Canter CE, Naftel DC, et al. The impact of heart failure severity at time of listing for cardiac transplantation on survival in pediatric cardiomyopathy. The Journal of Heart and Lung Transplantation. 2011;30(7):755–760. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2011.01.718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lipshultz SE. Ventricular dysfunction clinical research in infants, children and adolescents. Prog Pediatr Cardiol. 2000;12(1):1–28. doi: 10.1016/s1058-9813(00)00076-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lipshultz SE, Sleeper LA, Towbin JA, et al. The incidence of pediatric cardiomyopathy in two regions of the united states. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(17):1647–1655. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bublik N, Alvarez JA, Lipshultz SE. Pediatric cardiomyopathy as a chronic disease: A perspective on comprehensive care programs. Prog Pediatr Cardiol. 2008;25(1):103–111. doi: 10.1016/j.ppedcard.2007.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dayton JD, Kanter KR, Vincent RN, et al. Cost-effectiveness of pediatric heart transplantation. The Journal of Heart and Lung Transplantation. 2006;25(4):409–415. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2005.11.443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harmon WG, Sleeper LA, Cuniberti L, et al. Treating children with idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy (from the pediatric cardiomyopathy registry) Am J Cardiol. 2009;104(2):281–286. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2009.03.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grenier MA, Fioravanti J, Truesdell SC, et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor therapy for ventricular dysfunction in infants, children and adolescents: A review. Prog Pediatr Cardiol. 2000;12(1):91–111. doi: 10.1016/s1058-9813(00)00061-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rosenthal D, Chrisant MRK, Edens E, et al. International society for heart and lung transplantation: Practice guidelines for management of heart failure in children. The Journal of Heart and Lung Transplantation. 2004;23(12):1313–1333. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2004.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pahl E, Sleeper LA, Canter CE, et al. Incidence of and risk factors for sudden cardiac death in children with dilated cardiomyopathy: A report from the pediatric cardiomyopathy registry. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;59(6):607–615. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.10.878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dimas VV, Denfield SW, Friedman RA, et al. Frequency of cardiac death in children with idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. Am J Cardiol. 2009;104(11):1574–1577. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2009.07.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Laflamme MA, Murry CE. Regenerating the heart. Nat Biotech. 2005;23(7):845–856. doi: 10.1038/nbt1117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.ClinicalTrials.gov [Internet] Bethesda (MD): National Library of Medicine US; 2007. [cited 2012 June 8]. University of Louisville; Brigham and Women's Hospital Jewish Hospital and St. Mary's Healthcare. Cardiac Stem Cell Infusion in Patients With Ischemic CardiOmyopathy (SCIPIO) Available from: http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00474461 NLM Identifier: NCT00474461. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Burt RK, Loh Y, Pearce W, et al. Clinical applications of blood-derived and marrow-derived stem cells for nonmalignant diseases. JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association. 2008;299(8):925–936. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.8.925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Selem S, Hatzistergos KE, Hare JM. Cardiac Stem Cells: Biology and Therapeutic Applications. In: Atala A, Lanza R, Thomson J, Nerem R, editors. Principles of Regenerative Medicine. San Diego: Elsevier; 2011. pp. 327–346. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jackson KA, Majka SM, Wang H, et al. Regeneration of ischemic cardiac muscle and vascular endothelium by adult stem cells. J Clin Invest. 2001;107(11):1395–1402. doi: 10.1172/JCI12150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Asahara T, Toyoaki Isolation of putative progenitor endothelial cells for angiogenesis. Science. 1997;275(5302):964. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5302.964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zimmet J, Hare J. Emerging role for bone marrow derived mesenchymal stem cells in myocardial regenerative therapy. Basic Research in Cardiology. 2005;100(6):471–481. doi: 10.1007/s00395-005-0553-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jiang Y, Jahagirdar BN, Reinhardt RL, et al. Pluripotency of mesenchymal stem cells derived from adult marrow. Nature. 2002;418(6893):41–49. doi: 10.1038/nature00870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.D'Ippolito G, Howard GA, Roos BA, Schiller PC. Isolation and characterization of marrow-isolated adult multilineage inducible (MIAMI) cells. Exp Hematol. 2006;34(11):1608–1610. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2006.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kucia M, Reca R, Campbell FR, et al. A population of very small embryonic-like (VSEL) CXCR4+SSEA-1+Oct-4+ stem cells identified in adult bone marrow. Leukemia. 2006;20(5):857–869. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Jeevanantham V, Butler M, Saad A, et al. Adult Bone Marrow Cell Therapy Improves Survival and Induces Long-Term Improvement in Cardiac Parameters. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. 2012;126:551–568. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.086074. This meta-analysis synthesizes data from 50 studies to assess the efficacy of bone marrow cell transplantation in ischemic heart disease.

- 27.Schächinger V, Erbs S, Elsässer A, et al. Intracoronary bone Marrow–Derived progenitor cells in acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(12):1210–1221. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa060186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Traverse J, Henry T, Pepine CJ, et al. Effect of the use and Timing of Bone Marrow Mononuclear Cell Delivery on Left Ventricular Function After Acute Myocardial Infarction: The TIME Randomized Trial. JAMA. 2012:1–10. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.28726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Traverse J, Henry T, Ellis s, et al. Effect of Intracoronary Delivery of Autologous Bone Marrow Mononuclear Cells 2 to 3 Weeks Following Acute Myocardial Infarction on Left Ventricular Function: The LateTIME Randomized Trial. JAMA. 2011;306(19):2110–2119. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rupp S, Jux C, Boënig H, et al. Intracoronary bone marrow cell application for terminal heart failure in children. Cardiol Young. 2012 Oct;22(5):558–63. doi: 10.1017/S1047951112000066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Perin EC, Dohmann HFR, Borojevic R, et al. Transendocardial, autologous bone marrow cell transplantation for severe, chronic ischemic heart failure. Circulation. 2003;107(18):2294–2302. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000070596.30552.8B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Perin EC, Silva GV, Henry TD, et al. A randomized study of transendocardial injection of autologous bone marrow mononuclear cells and cell function analysis in ischemic heart failure (FOCUS-HF) Am Heart J. 2011;161(6):1078.e3–1087.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2011.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Perin EC, Willerson JT, Pepine CJ, et al. Effect of transendocardial delivery of autologous bone marrow mononuclear cells on functional capacity, left ventricular function, and perfusion in chronic heart FailureThe FOCUS-CCTRN trial. JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association. 2012;307(16):1717–1726. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.ClinicalTrials.gov [Internet] Bethesda (MD): National Library of Medicine (US); 2009. [cited 2012 June 8]. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI); Cardiovascular Cell Therapy Research Network (CCTRN). Effectiveness of Stem Cell Treatment for Adults With Ischemic Cardiomyopathy (The FOCUS Study) Available from: http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00824005?cond=cardiomyopathy&intr=stem+cell&cntry1=NA%3AUS&rank=1 NLM Identifier: NCT00824005. Identifier: NCT00824005. [Google Scholar]

- 35.ClinicalTrials.gov [Internet] Bethesda (MD): National Library of Medicine (US); 2011. [cited 2012 June 8]. University Medical Centre Ljubljana; The Methodist Hospital System Stanford University. Safety and Efficacy Study of Intramyocardial Stem Cell Therapy in Patients With Dilated Cardiomyopathy (NOGA-DCM) Available from: http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01350310?cond=heart+failure&intr=stem+cell&rank=14NLM Identifier: NCT01350310. [Google Scholar]

- 36.ClinicalTrials.gov [Internet] Bethesda (MD): National Library of Medicine (US); 2006. [cited 2012 June 8]. Johann Wolfgang Goethe University Hospitals. Progenitor Cell Therapy in Dilative Cardiomyopathy. Available from: http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00284713?cond=cardiomyopathy&intr=stem+cell&rank=1 6 NLM Identifier: NCT00284713. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lacis A, Erglis A. Intramyocardial administration of autologous bone marrow mononuclear cells in a critically ill child with dilated cardiomyopathy. Cardiol Young. 2011;21(01):110. doi: 10.1017/S1047951110001435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hare JM, Traverse JH, Henry TD, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, dose-escalation study of intravenous adult human mesenchymal stem cells (prochymal) after acute myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54(24):2277–2286. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.06.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Hare JM, Fishman JE, Gerstenblith G, et al. Comparison of allogeneic vs autologous bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells delivered by transendocardial injection in patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy: The POSEIDON randomized trial. JAMA. 2012:1–11. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.25321. This clinical trial is the first to study the safety and efficacy of allogeneic and autologous mesenchymal stem cell therapy for ischemic cardiomyopathy. The results are promising since mesenchymal stem cell therapy reduced ventricular remodeling as well as improved patient functional capacity and quality of life.

- 40.Nagaya N, Kangawa K, Itoh T , et al. Transplantation of mesenchymal stem cells improves cardiac function in a rat model of dilated cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2005;112(8):1128–1135. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.500447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zeinaloo A, Zanjani KS, Bagheri MM, Mohyeddin-Bonab M, Monajemzadeh M, Arjmandnia MH. Intracoronary administration of autologous mesenchymal stem cells in a critically ill patient with dilated cardiomyopathy. Pediatr Transplant. 2011;15(8):E183–E186. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3046.2010.01366.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.ClinicalTrials.gov [Internet] Bethesda MD: National Library of Medicine (US); 2011. [cited 2012 June 8]. University of Miami; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI). PercutaneOus StEm Cell Injection Delivery Effects On Neomyogenesis in Dilated CardioMyopathy (The POSEIDON-DCM Study) Available from: http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01392625?cond=cardiomyopathy&intr=stem+cell&cntry1=NA%3AUS&rank=2 NLM Identifier: NCT01392625. [Google Scholar]

- 43.ClinicalTrials.gov [Internet] Bethesda (MD): National Library of Medicine (US); 2010. [cited 2012 June 8]. Qingdao University. Intramuscular Injection of Mesenchymal Stem Cell for Treatment of Children With Idiopathic Dilated Cardiomyopathy. Available from: http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01219452?cond=cardiomyopathy&intr=stem+cell&rank=1 NLM Identifier: NCT01219452. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yoon PD, Kao RL, Magovern GJ. Myocardial regeneration. Transplanting satellite cells into damaged myocardium. Texas Heart Institute Journal. 1995;22:119–125. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Menasché P, Alfieri O, Janssens S, et al. The myoblast autologous grafting in ischemic cardiomyopathy (MAGIC) trial: first randomized placebo-controlled study of myoblast transplantation. Circulation. 2008;117(9):1189–1200. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.734103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Menasché P. Skeletal myoblasts for cardiac repair: Act II? J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52(23):1881–1883. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.07.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Reinecke H, Poppa V, Murry CE. Skeletal muscle stem cells do not transdifferentiate into cardiomyocytes after cardiac grafting. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2002;34(2):241–249. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.2001.1507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Okada M, Payne TR, Zheng B, et al. Myogenic endothelial cells purified from human skeletal muscle improve cardiac function after transplantation into infarcted myocardium. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52(23):1869–1880. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.07.064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hierlihy AM, Seale P, Lobe CG, Rudnicki MA, Megeney LA. The post-natal heart contains a myocardial stem cell population. FEBS Lett. 2002;530(1–3):239–243. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)03477-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Beltrami AP, Barlucchi L, Torella D, et al. Adult cardiac stem cells are multipotent and support myocardial regeneration. Cell. 2003;114(6):763–776. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00687-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Oh H, Bradfute SB, Gallardo TD, et al. Cardiac progenitor cells from adult myocardium: Homing, differentiation, and fusion after infarction. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2003;100(21):12313–12318. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2132126100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Matsuura K, Nagai T, Nishigaki N, et al. Adult cardiac sca-1-positive cells differentiate into beating cardiomyocytes. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2004;279(12):11384–11391. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M310822200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bearzi C, Rota M, Hosoda T, et al. Human cardiac stem cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2007;104(35):14068–14073. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706760104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Williams A, Trachtenberg B, Velazquez D, et al. Intramyocardial Stem Cell Injection in Patients with Ischemic Cardiomyopathy: Functional Recovery and Reverse Remodeling. Circ Res. 2011;108(7):792–796. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.242610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hatzistergos K, Quevedo H, Oskouei BN, et al. Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells stimulate cardiac stem cell proliferation and differentiation. Circ Res. 2010;107(7):913–922. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.222703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Messina E, De Angelis L, Frati G, et al. Isolation and expansion of adult cardiac stem cells from human and murine heart. Circ Res. 2004;95(9):911–921. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000147315.71699.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Davis DR, Kizana E, Terrovitis J, et al. Isolation and expansion of functionally-competent cardiac progenitor cells directly from heart biopsies. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2010;49(2):312–321. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2010.02.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chimenti I, Smith RR, Li Te, et al. Relative roles of direct regeneration versus paracrine effects of human cardiosphere-derived cells transplanted into infarcted mice. Circ Res. 2010;106(5):971–980. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.210682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Makkar RR, Smith RR, Cheng K, et al. Intracoronary cardiosphere-derived cells for heart regeneration after myocardial infarction (CADUCEUS): A prospective, randomised phase 1 trial. Lancet. 2012;379(9819):895–904. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60195-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Mishra R, Vijayan K, Colletti EJ, et al. Characterization and functionality of cardiac progenitor cells in congenital heart patients. Circulation. 2010;123(4):364–73. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.971622. This study explores the capacity of human cardiac progenitor cells in young patients with nonischemic congenital heart defects. It discusses their potential to repair congenital heart defects.

- 61.Simpson D, Mishra R, Sharma S, et al. A Strong Regenerative Ability of Cardiac Progenitor Cells in Neonatal Heart Patients. Circulation. 2012;126(11) Suppl 1:S46–S53. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.084699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]