Abstract

When researchers evaluate adult outcomes for individuals with intellectual and/or developmental disabilities (ID/DD), the perspective of families is not always considered. Parents of individuals with ID/DD (n=198) answered an online survey about their definition of a successful transition to adulthood. Content analysis was used to describe themes and ideas present in responses. Rather than focusing only on developmental tasks of adulthood, such as living independently, being competitively employed, and maintaining friendships, responses reflected a more varied and dynamic view of success in adulthood, taking into account the fit between the person with ID/DD and his or her environment. As services are developed and implemented for adults with ID/DD, it is important to consider the full range of goals families have for their son or daughter’s successful transition to adulthood.

The transition to adulthood is stressful for families of typically developing youth (Silverberg, 1996), and even more so for families of youth with intellectual and/or developmental disabilities (ID/DD) (Neece, Kraemer, & Blacher, 2009; Thorin & Irvin, 1992; Whitney-Thomas & Hanley-Maxwell, 1996). One likely reason for heightened stress in these families is the added burden of finding, coordinating, and financing adult services (Thorin & Irvin, 1992). Young adults with ID/DD and their parents must become their own advocates for services and supports after the youth leaves high school (Austin, 2000; Everson & Moon, 1987).

With the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), the US Department of Education put supports in place to facilitate the transition to adulthood for youth with disabilities. For example, IDEA recommends that the school begin transition planning at age 14, and transition to adulthood must be addressed no later than age 16. Furthermore, it allows these youth to remain under the support umbrella of the public school system through the age of 22. Despite this mandated transition support, it has been suggested that many schools fall short of meeting the needs of transitioning students with ID/DD in areas such as engaging student and family participation; setting goals based on students’ skills and interests; and ensuring full participation in employment, postsecondary education, and independent living opportunities (Johnson, Stodden, Emanuel, Luecking, & Mack, 2002). Indeed, research has shown that young adults with ID/DD are less likely than their typically developing peers to be employed, to enroll in postsecondary education, and to live independently after high school (Newman, Wagner, Knokey, et al., 2011).

Evaluating and defining successful adult outcomes

The extant literature typically defines a successful transition to adulthood as the achievement of certain developmental tasks. Objective “role transitions,” such as finishing school, finding full-time paid employment, getting married, and starting a family, are the most common criteria used to evaluate success in adulthood for typically developing youth (Arnett, 2001; Hogan & Astone, 1986; Settersten & Ray, 2011). These criteria are often applied in outcomes studies of adults with ID/DD, as well. For example, the National Longitudinal Transition Study 2 (NLTS2), which followed a national sample of youth receiving special education services, focused on postsecondary education, employment, independence, and relationships as markers of positive adult outcomes (Newman et al., 2011). Furthermore, studies of individuals with autism spectrum disorders (ASD) have assigned numerical ratings of good versus poor outcomes by measuring independence in three categories: work, living, and friendships (Billstedt, Gillberg, & Gillberg, 2005; Eaves & Ho, 2008; Farley et al., 2009; Howlin, Goode, Hutton, & Rutter, 2004). By these standards, successful transition outcomes include living in one’s own home, having friends, and being independently employed. However, these role transitions are becoming less reliable indicators of adulthood, as changing economic and social conditions continue to alter the traditional path to adulthood for all youth (e.g., it is becoming more difficult for young adults to find employment; Furstenberg, Raumbaut, & Settersten, 2005; Settersten & Ray, 2011). They may be particularly unreliable indicators of adulthood for youth with ID/DD, who often face added challenges due to cognitive impairments and impairments in daily living skills.

Accordingly, many have stressed the importance of redefining what it means to successfully transition to adulthood, both in the general and ID/DD populations (Arnett, 2000, 2001; Halpern, 1993; Henninger & Taylor, 2013; Ruble & Dalrymple, 1996; Taylor, 2009). For example, the Emerging Adulthood Theory (Arnett, 2000) posits that the period between adolescence and adulthood can be defined by the development of an identity independent from parents, especially in the areas of finances and decision-making. Arnett (2001) found that adolescents and adults were most likely to endorse individualistic criteria (i.e. responsibility for oneself, establishing a personal value system, relating to parents as adults, and financial independence) as important for becoming an adult. In fact, “role transitions” such as getting married and finding full-time employment were ranked of lowest importance. These findings support a definition of adulthood that is focused on the individual’s perspective of his or her independence, rather than on “normative” role transitions.

Another alternative perspective, offered by Halpern (1993) as well as Ruble and Dalrymple (1996), suggests that success in adulthood for individuals with ID/DD in particular is the achievement of a balance between subjective and objective goals, or finding a “person-environment fit.” While objective societal values such as competitive employment and independent living are important, they do not capture the complete picture of what it means to become an adult. With the person-environment fit perspective, these goals are evaluated and adjusted within the individual’s unique context. A balance between objective goals and the individual’s subjective experience results in the person’s optimal well-being in adulthood. For example, not only is it important whether an individual with ID/DD is employed, but also how well the job fits his or her interests and provides a level of support adequate for success. What Halpern argues is not that the developmental tasks framework is irrelevant, but that it is incomplete without the consideration of the person with ID/DD’s subjective experience.

Outcome goals of families of youth with ID/DD

The perspectives of parents of individuals with ID/DD also challenge the traditional criteria of success in adulthood as independence in work, living, and social relationships. Hanley-Maxwell and colleagues (1995) found that parents’ concerns for their child’s future consisted of: (1) a safe, happy residential situation; (2) strong social networks; and (3) constructive use of free time. Another study found that parents’ most common transition concerns were their child’s interactions with others, ability to care for oneself, responsibility, and sexuality (Thorin & Irvin, 1992). A survey of parents of children with ASD identified safety from harm as the most concerning element of their child’s adult outcome (Ivey, 2004). Neece and colleagues (2009) found that the youth’s overall mental health and well-being were the most critical factors associated with parents’ satisfaction with the transition to adulthood. Although these existing studies focused on transition concerns or satisfaction, they indicate that parents’ goals for the transition to adulthood are likely more wide-ranging than just independent living, employment, and friendships.

The present study

Although studies have examined families’ transition concerns and satisfaction, researchers have yet to explore how families define success in adulthood for their son or daughter with ID/DD. In the present study, we identified criteria for success in adulthood based on open-ended responses from parents of children with ID/DD. Given the paucity of research in this area, our analyses were mainly exploratory. However, we did expect that themes of transition success identified in the open-ended responses would be more far-reaching and dynamic than work, residence, and friendships due to (1) the call for new perspectives on success in adulthood in both disability and non-disability groups (Arnett, 2000, 2001; Halpern 1993; Henninger & Taylor 2013; Ruble & Dalrymple, 1996; Taylor, 2009), as well as (2) the existing literature on parents’ many transition concerns for youth with ID/DD (Hanley-Maxwell et al., 1995; Ivey, 2004; Neece et al., 2009; Thorin & Irvin, 1992). In addition, we explored differences in parental definitions of success in adulthood by child age. Because formal transition planning often begins in high school at age 14, we chose to analyze differences across parents of children in the following three age groups: not yet in high school (prior to transition planning), in high school (during transition), and post-high school (after transition).

Methods

Participants

The participants were parents of individuals with ID/DD (N=198) who answered an Internet survey about transitioning to adulthood. Characteristics of the respondents (parents) and their son or daughter with ID/DD are found in Table 1. The majority of respondents were mothers (89.4%) and Caucasian (92.8%). Parents tended to be highly educated, as just over three-fourths were college graduates, and about one-third had completed some graduate work. About 20% of parents had completed some college, and the remaining 4% were high school graduates.

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics

| n | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|

| Parental Characteristics | ||

| Sex | ||

| Female | 177 | 89.4% |

| Male | 21 | 10.6% |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Caucasian | 180 | 92.8% |

| African American | 9 | 4.6% |

| Hispanic | 2 | 1.0% |

| Other | 3 | 1.5% |

| Highest Level of Education | ||

| High school graduate | 8 | 4.1% |

| Some college | 39 | 19.9% |

| College graduate | 87 | 44.4% |

| Graduate work | 62 | 31.6% |

| Characteristics of Son/Daughter with ID/DD | ||

| Disability* | ||

| Autism Spectrum Disorder | 84 | 42.4% |

| Intellectual/ Developmental Disability | 65 | 32.8% |

| Down Syndrome | 55 | 27.8% |

| Emotional Disturbance or Condition | 18 | 9.1% |

| Cerebral Palsy | 15 | 7.6% |

| Health Condition | 14 | 7.1% |

| Unspecified Developmental Disability | 11 | 5.6% |

| Sensory Impairment (Hearing, vision) | 10 | 5.1% |

| Fragile X Syndrome | 3 | 1.5% |

| Williams Syndrome | 3 | 1.5% |

| Prader-Willi Syndrome | 1 | 0.5% |

| Other Condition | 25 | 12.6% |

| Age Group | ||

| Pre-high school | 61 | 30.8% |

| In high school | 53 | 26.8% |

| Post-high school | 84 | 42.4% |

| Current Residence | ||

| With parent | 176 | 89.3% |

| Family home with another relative | 3 | 1.5% |

| Group home | 2 | 1.0% |

| Supervised apartment | 3 | 1.5% |

| Lives with spouse/significant other or friend |

3 | 1.5% |

| By self (in home or apartment) | 4 | 2.0% |

| Larger facility | 1 | 0.5% |

| Residential school | 2 | 1.0% |

| Other | 3 | 1.5% |

Note. Because respondents could check all disabilities that applied to their son or daughter, disability percentages add up to more than 100.

Parents reported their son or daughter’s disability diagnoses from a checklist of 12 intellectual and/or developmental disabilities. They were allowed to check all disabilities that applied to their child, so percentages sum to more than 100. The most common disability reported by parents was ASD (42.4%), followed by intellectual and developmental disability (IDD; 32.8%), and Down syndrome (DS; 27.8%). The remaining conditions were endorsed by fewer than 10% of parents in the sample. On average, the respondents’ sons and daughters with ID/DD were 18 years old (M=18.48), although the large age range (2 – 47 years, SD=8.31) represents a wide range of developmental stages. Approximately 30% (n = 61) of the sons and daughters had not yet entered high school. Of this group of children, 13.1% (n = 8) were not yet school-age, 50.8% (n = 31) were in elementary school, and 36.1% (n = 22) were in middle or junior high school. About one-quarter (n = 53) of participants’ sons or daughters were currently in high school. The remaining respondents’ sons or daughters had exited high school (42.4%, n = 84). One-quarter (n = 21) of those who had exited were currently enrolled in college or a postsecondary education program, 70.2% (n = 59) had exited high school but were not in a postsecondary education program, and 4.8% (n = 4) had exited but did not indicate postsecondary education program status. Most parents (89.3%) reported that their son or daughter was living at home with them.

Procedure

The survey link was disseminated through various disability networks and local Tennessee chapters of disability organizations. Participants were asked to answer a number of demographic questions, as well as the open-ended question, “Thinking about your son or daughter’s strengths and difficulties, what would a successful transition to adulthood look like for him or her?” There were no limits or guidelines as to how long the response could be for this question.

Open-ended responses were analyzed using qualitative content analysis (Elo & Kyngas, 2008; Graneheim & Lundman, 2004; Hsieh & Shannon, 2005). Most of the participants’ responses contained multiple ideas (which we call “phrases”) within the same response. In order to develop categories that were mutually exclusive, we chose to code at the level of idea or “phrase,” as opposed to applying one code to each response in its entirety (following guidelines by Graneheim & Lundman, 2004). As a result, some of the participants’ responses had multiple codes, but each phrase within the response was mutually exclusive, having only one code.

To begin the process of developing coding categories, the investigator (first author) read through all of the responses several times to become familiar with the data set as a whole (Tesch, 1990). Next, notes were made on initial impressions, thoughts, and key words in the data (Hsieh & Shannon, 2005). These notes led to preliminary codes, which were applied to each of the phrases within the responses. New codes were created and current codes were revised when a phrase did not fit (either no code accounted for the phrase, or the phrase fit into multiple codes). The investigator then clustered these codes to create the first draft of coding category definitions. The categories and their definitions were revised with a second investigator (senior author) and applied to all of the responses in the data set.

After the responses were coded, the categories were evaluated again with the second investigator. Both investigators coded a random 10% of the data and achieved over 80% agreement (# disagreements divided by total codes). Discrepancies were discussed, and categories were refined again. After a few more iterations of this process, both investigators agreed that the categories and their definitions accurately reflected themes in the data. The result was thirteen possible codes. Eleven codes described distinct themes in the responses; an “other” code represented ideas that were not frequent enough to be a distinct category; and a last code was assigned to responses that did not answer the question. To get a code of “does not answer question,” no part of the response (i.e., no phrases within the response) could be coded as an answer to the question posed to the participant.

After the two investigators came to agreement on the coding categories, reliability was established with an independent coder (graduate student), who coded a random selection of 10% of the participants’ responses (n=23) containing 66 individual phrases. The original 66 codes were compared to the independent coder’s, and 88% agreement was reached with a kappa of 0.86. According to Landis and Koch (1977), kappa values above 0.80 are considered “almost perfect” agreement. At this point, we felt that reliability had been established for the coding categories.

Results

Category Frequencies

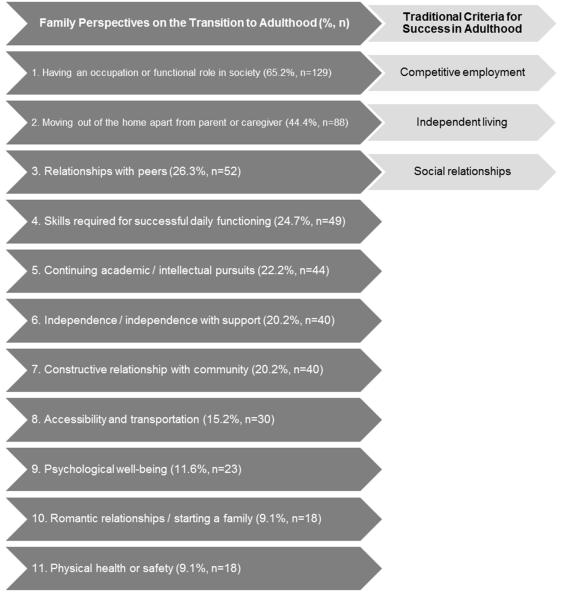

First, we examined the frequency of each category. It was common for participants to give responses to the open-ended question that contained more than one “theme” or phrase. The mean number of phrases per participant response was 2.84, and the mode was 2. Approximately 17% (16.7%) of responses contained 4 or more themes, with a maximum of 9. Frequencies for each category are presented in Figure 1, and category definitions can be found in Appendix A.

Figure 1.

Comparison/contrast between family perspectives and traditional criteria for success in adulthood. The left column depicts the frequency of study participants who mentioned each theme as important to success in adulthood. The right column lists the traditional criteria often considered and evaluated when defining adult success. It is important to note that the percentages reflect the number of participants who received each code. Because a single response could contain multiple phrases, participants could get more than one code. Thus, percentages add up to more than 100.

1. Having an occupation or functional role in society

The most frequent theme present in the responses was “Having an occupation or functional role in society.” Nearly two-thirds (65.2%) of participants mentioned something about vocation as necessary for a successful transition. Many of the respondents expressed the goal of paid, full-time employment. However, the data revealed a more dynamic construct beyond simply having a paid job. Participants wrote about the importance of being able to find and apply for a job as well as having job skills training. Many responses indicated that having a job did not necessarily mean paid or full-time employment. Some named part-time work, supported employment, volunteering, or workshop environments as important. The theme behind this code seemed to be the goal of having a productive occupation fitting the needs and abilities of the individual with ID/DD. For this reason, general feelings of productivity and contributing to the community were also coded in this category.

2. Moving out of the home, apart from parent or caregiver

The next most frequently mentioned element of a successful transition was “Moving out of the home, apart from parent or caregiver.” This category was mentioned by 44.4% of the respondents. A phrase was coded in this category if it indicated any living arrangement other than with the parent or primary caregiver. This ranged from living independently in one’s own home to living in a group home with full support. As in the first category, the theme behind this code seemed to be a goal of living in a situation appropriate for that particular individual. Nearly all of the participants who mentioned living arrangements agreed that the individual with ID/DD should be living somewhere other than with their parents for a successful transition to adulthood.

3. Relationships with peers

“Relationships with peers,” was indicated as a goal of the transition to adulthood by approximately one-quarter (26.3%) of participants. To be coded in this category, the respondent had to talk about relationships with individuals or groups of peers. Approximately 6% of responses in this category (n = 3) mentioned relationships with both non-related peers and family members (e.g., “relationships with friends and family”) as an important aspect of transition success. Given the small percentage of individuals who mentioned family, and that family was always mentioned in conjunction with friends, we coded “relationships with friends and family” in this category. This theme is distinct from attending social activities or participating in other community functions because the focus is on the relationship, not the event.

4. Skills required for successful daily functioning

With a frequency of 24.7%, daily living skills was a commonly mentioned theme. This included skills such as money managing, cooking, and paying bills on time. In addition, respondents sometimes expressed the importance of social communication or behavioral skills. Phrases were coded in this category when the skill itself was discussed as the primary goal. However, when parents discussed skills as means to a separate aim, responses were coded in the category representing that end goal. For example, phrases such as “needs meaningful speech practice and conversation and communication,” and “continuation of skills she is working on: cooking, community navigation, self-help,” were coded in this category. Alternatively, a phrase like “skills or knowledge to maintain a job,” was coded in the category corresponding with the end goal (in this case, Having an occupation or functional role in society).

5. Continuing academic or intellectual pursuits

The goal of “Continuing academic or intellectual pursuits” was present in about one-fifth (22.2%) of participants’ responses. Some phrases in this category mentioned specific institutions for education – community college, technical college, university, finishing high school. Other responses expressed a goal of more general intellectual stimulation or growth.

6. Independence/ independence with support

The theme of “Independence/ independence with support” appeared in 20.2% of the participants’ responses. The main idea behind this category was a sense of autonomy other than in the physical living arrangement. This could include, for example, financial independence, making one’s own decisions, and being responsible for oneself. On the other hand, many respondents expressed the need for support in a variety of forms, including physical, emotional, and daily living supports. Support was often presented in responses as complimentary to independence. For example, participants used phrases such as “independence with support” and “enough support for him to live as independently as possible.” For this reason, responses containing ideas of “support” were also coded here, as support allows the individual a maximum level of independence.

7. Constructive relationship with community

This was one of the most difficult categories to define, as 20.2% of respondents talked about the importance of the individual fitting into the community in one way or another. This relationship was bi-directional – ideas could be focused on the individual participating in the community or the community providing opportunities for the individual. The former includes the individual’s participation in recreational, social, and/or leisure activities in the community. A community providing support to the individual includes institutions such as a welcoming church that provides a network of support.

8. Accessibility and transportation

Having easy access to places, services, or other necessities was mentioned by 15.2% of respondents. This category was most often expressed in terms of transportation, such as getting a driver’s license, being able to navigate public transportation, or even being able to walk to destinations.

9. Psychological well-being

The well-being of the individual with ID/DD was cited as an important component of a successful transition to adulthood for 11.6% of participants. This took the form of positive internal states, moods, or emotions. A few examples include happiness, compassion, determination, self-confidence, and feeling challenged.

10. Romantic relationships and/or starting a family

For 9.1% of respondents, being romantically involved with another person or starting a family was an important element of successful adulthood.

11. Physical health or safety

Eighteen respondents (9.1%) listed health or safety as important for the transition to adulthood. This includes both being in good physical health and being safe from danger or harm.

Other

A number of the responses (16.2%) contained themes that did not fit well into any of the other categories. These were goals of the transition to adulthood that were mentioned too infrequently to be their own category. Some examples include having spending money, being able to travel, and being surrounded by compassionate caretakers. In other instances, respondents mentioned themes that were too general or abstract to be coded as a defined goal of adulthood. These included constructs such as morality and maturity.

No part of the response answers the question

Fifteen participants (7.6%) responded to the open-ended question, but their responses did not answer the question. Some responded with “don’t know” or “there will be no change.” Others described what was currently happening in the life of their son or daughter, or they reflected on the way things were in the past.

Frequency of Categories by Age Group

Second, we ran chi-square analyses to compare individual category frequencies among three age groups: pre-high school, high school, and post-high school. The pre-high school group included parents whose son or daughter was in elementary school, middle school, or not yet school-age. The post-high school group included all parents whose son or daughter had exited high school. This could include those enrolled in a postsecondary education program, engaging in work or other daytime activities, or doing nothing. Results of these analyses are summarized in Table 2. The relationship between theme frequency and age group was significant for two themes; “Continuing academic / intellectual pursuits,” and “Having an occupation or functional role in society.” Respondents whose son or daughter had already exited high school were about one-half as likely to include the theme “Continuing academic / intellectual pursuits” relative to parents of those still in high school or who had not yet entered high school. Similarly, parents with a son or daughter in the post-high school group expressed the theme, “Having an occupation or functional role in society,” less frequently than those in the pre-high school and high school groups.

Table 2.

Percentage of Respondents who Endorsed Each Theme by Son/Daughter Age Group

| Theme | Pre-high school |

In high school |

Post- high school |

X2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Having an occupation or functional role in society | 70.5% | 75.5% | 54.8% | 7.25* |

| 2. Moving out of the home, apart from parent or caregiver | 52.5% | 41.5% | 40.5% | 2.31 |

| 3. Relationships with peers | 31.1% | 24.5% | 23.8% | 1.10 |

| 4. Skills required for successful daily functioning | 19.7% | 28.3% | 26.2% | 1.30 |

| 5. Continuing academic or intellectual pursuits | 31.1% | 26.4% | 13.1% | 7.40* |

| 6. Independence/independence with support | 18.2% | 20.8% | 21.4% | 0.27 |

| 7. Constructive relationship with community | 18.0% | 30.2% | 15.5% | 4.62 |

| 8. Accessibility and transportation | 13.1% | 15.1% | 16.7% | 0.35 |

| 9. Psychological well-being | 14.8% | 11.3% | 9.5% | 0.95 |

| 10. Romantic relationships and/or starting a family | 13.1% | 7.5% | 7.1% | 1.73 |

| 11. Physical health or safety | 11.5% | 13.2% | 4.8% | 3.41 |

p is significant at the .05 level

Note. Because respondents could have answers that contain more than one theme, percentages add up to more than 100.

Discussion

This study offers a unique insight into what parents of individuals with ID/DD value for a successful transition to adulthood. Typically, evaluation of adult outcomes in the extant literature is based on objective criteria in three domains: relationships, employment, and independent living (Billstedt et al., 2005; Carr, 2008; Eaves & Ho, 2008; Farley et al., 2009; Howlin et al., 2004). However, alterative frameworks such as Emerging Adulthood (Arnett, 2000) and person-environment fit (Ruble and Dalrymple, 1996) have been suggested as more accurate representations of what it means to transition from adolescence to adulthood. Building on these theoretical perspectives, as well as previous work describing parental concerns (Hanley-Maxwell et al., 1995; Ivey, 2004; Thorin & Irvin, 1992) and satisfaction (Neece et al., 2009) for their son or daughter’s adult life, this study identified criteria for success in adulthood based on open-ended responses from parents of children with ID/DD. The results depicted in Figure 1 suggested that families’ goals for their son or daughter with ID/DD reach far beyond conventional criteria of success in adulthood in both depth of criteria and breadth of content.

Depth of criteria for determining success in adulthood

The three most frequently mentioned themes fit with the traditional criteria of independence in work, living, and relationships; however, parents discussed a considerably nuanced set of criteria within these three domains. For example, parents agreed with the extant literature that occupation is an important piece of adulthood. However, the depth of parental definitions of success in this area reached beyond the constrained criterion of full-time competitive employment. Parents seemed to value a range of occupational outcomes that take into account their son or daughter’s skills and interests, just one of which was competitive employment. The themes, “Moving out of the home, apart from parent or caregiver” and “Relationships with peers,” encompassed a similar depth of outcomes in contrast to common objective criteria of independent living and friendships.

Overall, open-ended responses tended to reflect a person-environment fit perspective (Halpern 1993; Ruble & Dalrymple 1996). While parents often agreed with the subject matter of the developmental tasks framework (employment, independent living, and relationships), their underlying aims were rarely objective. In other words, success in adulthood was often described subjectively as the individual reaching his or her full potential within domains such as work and residential placement, rather than simply stating objective criteria such as competitive employment and independent living as essentials to success. For example:

“A successful transition would be developing a network of positive relationships with individuals in the community with similar interests as himself. Would also include independent living if this is important to him. Would include maximizing his academic strengths to fullest, and helping him continue to find ways to be happy and secure in his differences.” Or,

“to acquire the skills to live as independently as possible and to be able to have a productive life and job”

Congruent with the person-environment fit perspective, the recurrent theme throughout categories was the idea of a balance between individual needs and environmental supports. This balance should be reflected in both transition planning and adult outcome research, as parents’ criteria for their son or daughter’s success is often qualified with this relationship.

Breadth of content in definitions of success in adulthood

In addition to these nuanced perspectives on traditional criteria, parent perspectives extended across 11 themes, in contrast with the most commonly cited three in the extant literature. It is perhaps unsurprising that “Skills required for successful daily functioning” was mentioned almost as frequently as “Relationships with peers.” Among individuals with ASD, studies have found that independence in activities of daily living is an important predictor of employment and other adult outcomes (Farley, et al., 2009; Taylor & Mailick, in press; Taylor & Seltzer, 2011). Thus, interventions that involve skills training should be a major focus of future transition to adulthood initiatives. Similarly, postsecondary education is often emphasized in transition planning, particularly for those without an intellectual disability. The frequency with which parents of children with ID/DD mentioned “Continuing academic / intellectual pursuits” demonstrates that many of these families also place a great deal of importance on the continuation of intellectual growth, regardless of whether their son or daughter’s transition plan incorporates attendance at a formal postsecondary institution. Transition planning and future research on adult outcomes for individuals with ID/DD should consistently address these domains of success in adulthood, as they seem to be high priorities for families.

In addition to these five most frequent themes, general independence was also an aspect of transition success mentioned by a substantial number of respondents. Common examples for this code in the open-ended responses were “financial and legal independence,” “making own decisions,” and “being responsible for oneself.” This theme closely resembles Arnett’s theory of Emerging Adulthood, which emphasizes autonomy from parents in areas like finances and decision making as most important for becoming an adult (Arnett, 2000; 2001).

The theme “Constructive relationship with community” was mentioned as frequently as general independence, and should be considered in planning interventions to improve transition outcomes. The extant research suggests a few promising examples of community services that might best meet individuals’ needs in adulthood. For example, Billstedt, Gillberg, & Gillberg (2011) found that the presence of daytime recreational activities was related to well-being for adults with ASD. In addition, Farley et al. (2009) suggested that the community inclusion fostered by high religious participation in their sample of adults with ASD contributed to their positive adult outcomes relative to other samples of adults with ASD. Daytime recreational activities and community inclusion are two environmental supports that have the potential to improve outcomes, and should be studied further as possible targets for transition intervention.

Transportation, psychological well-being, romantic fulfillment, and physical safety were also among themes important to families. Overall, the number of themes was almost four times the number of criteria typically used to measure global outcomes in adults with ID/DD. Future studies should therefore consider a wider range of outcomes beyond work, living, and relationships, to give a more complete picture of the transition to adulthood for individuals with ID/DD.

Outcome goals and age group

A few differences in family perspectives emerged across parents of children in three age groups: those whose children were not yet in high school, those with a child in high school, and parents of adult children who had exited high school. Although a previous study found no differences in expectations between parents of youth in high school and youth who had recently exited high school (Kraemer & Blacher, 2001), our results indicate that perspectives on transition success for parents of adults with ID/DD diverged somewhat for those whose son or daughter had exited high school relative to those who were still in the school system. In particular, parents of older individuals seemed less concerned with goals like postsecondary education and occupation than parents of children in early childhood through high school, and these differences did not appear to be accounted for by differences in diagnoses among age groups (analyses available from corresponding author). These results indicate that while perspectives of a successful transition to adulthood may be relatively consistent across parents of young children and adolescents, parents whose sons or daughters have already transitioned out of high school might be less likely to see goals like postsecondary education and occupation as essential to adult success. Future research should examine whether age-related shifts in the importance parents place on these activities are related to difficulties after high school exit in finding appropriate supports and programs to foster success in postsecondary education and employment.

Study Limitations

Several limitations of this study should be noted. First, because we used an Internet survey based on convenience sampling, respondents are not representative of all families of individuals with ID/DD. A sample that includes families with a wider range of educational, socioeconomic, and cultural backgrounds may result in different or more varied perspectives on a successful transition to adulthood for individuals with ID/DD. In addition, perspectives on a successful transition may differ between parents of individuals with ID/DD, and individuals with ID/DD themselves. Just as the voice of the student with ID/DD is an important part of transition planning in the schools, it should also be incorporated into future research endeavors focused on defining success in adulthood. Finally, because we conducted an Internet survey, we were unable to confirm specific ID/DD diagnoses endorsed by parents, limiting our confidence in our ability to compare perspectives across disability groups. Future studies comparing perspectives of families of youth with a variety of confirmed diagnoses will be helpful for individualizing transition plans.

Implications

Our finding that parents had more expansive views on a successful transition to adulthood for youth with ID/DD, relative to conventional definitions, has significant implications for future transition planning. According to an NLTS2 report, school staff involved in postsecondary service planning for students with disabilities most often cite the need for postsecondary education accommodations, vocational training, and/or or employment services (Cameto, Levine, & Wagner; 2004). While these services coincide with families’ transition goals of postsecondary education and employment, many of the additional elements of transition success mentioned by parents in this study (i.e. physical health, psychological well-being, and transportation) are not always addressed in formal transition planning. Expanding the focus to include these additional goals may have the potential to support success in primary goals of postsecondary education and employment. For example, successful participation in a postsecondary or vocational setting might depend on the person’s access to health, mental health, and/or transportation services (Johnson et al., 2002).

When planning for the difficult task of transitioning from adolescence to adulthood, it is essential that services meet the specific needs of youth with ID/DD and their families. If families are dissatisfied with the transition process, their overall well-being may suffer as a result (Neece et al., 2009). As we begin to address the efficacy of transition planning and adult services, we must start by identifying what families of youth with ID/DD value most for success in adulthood. Our findings suggest that family goals are more nuanced and expansive than conventional perspectives on transition planning and success in adulthood. The perspective of these families is important in guiding future research and practice in the field of adult outcomes.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (K01 MH092598, J. L. Taylor, PI) and Autism Speaks (J. L. Taylor, PI). Core support was provided by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (P30 HD15052, E. M Dykens, PI).

Appendix A. Coding Category Definitions for Open-Ended Responses

- Having an occupation or functional role in society

- Response talks about vocational services, job skills, or the occupation itself

- A main idea in the response consists of finding, acquiring, keeping, and/or enjoying any kind of occupation

- Getting a job – jobs being available, easy to find, easy to apply

- Characteristics – paid or volunteer, full time or part time, supported or independent, meaningful, enjoyable, valuable

- Includes vocational services, training, and job skills

- Includes workshop environments and volunteer work

- Includes general productivity (or feeling productive), contributing to society/community, having a purpose

- Moving out of the home, apart from parent or caregiver

- Respondent talks about a residential status that implies any arrangement away from parent or caregiver

- Includes living alone, with others, with friends, in group home, in apartment, in own home, with supervision/support, in nursing home

- Includes the phrase “independent living”

- Excludes living arrangements only with parent or caregiver (coded “other”)

- Relationships with peers

- Respondent talks about spending time or establishing relationships with individual peers or groups of peers

-

If respondent mentions relationships with “friends and family,” code here.*If response indicates the desire for peer interaction/relationships, code here; if response indicates the desire for opportunities or places in the community to meet peers, code “Constructive relationship with community.”

- Skills required for successful daily functioning

-

Specific daily living skills (i.e. money managing, cooking, paying bills), as well as social communication and behavioral skills*If response states “skills” or lists specific daily living skills only, code here; if response indicates that skills are needed for another category to be obtained (i.e. “to acquire the skills to live as independently as possible”), code as that category (in this case, independence/independence with support).

-

- Continuing academic or intellectual pursuits

- Any form of institutional post-secondary education – vocational school, community college, taking classes, etc.

- OR any form of intellectual stimulation or growth – reaching maximum intellectual potential, being educated

- Includes completing high school

- Independence/independence with support

- Respondent implies a general state of feeling independent, including financial and legal independence, making own decisions, being responsible for oneself, etc.

- Includes general supports or supervision, as these aid the individual in independent day-to-day functioning

-

Excludes the phrase “independent living” or “living independently,” as these are typically used to describe an individual’s residential status and should therefore be coded “moving out of the home, apart from parent or caregiver”*If response refers to general support, code “independence/independence with support;” if response indicates that support is needed for another category, code as that category.

- Constructive relationship with communityp

- Includes recreational, social, and leisure activities

- Includes the desire for a community (often church community) that extends support to individual

- Accessibility and transportation

- Response implies an ability to easily access places, services, or things

- Most often in terms of transportation – includes getting driver’s license, being able to navigate public transportation; but could be through walking or living in close proximity

- Psychological well-being

- Response implies a positive internal state, including emotions, moods, and attitudes

-

Includes determination, self-confidence, happiness, dignity, compassion, positivity, motivation, interest, personal spirituality, self-control, being challenged, pride*If quality listed in response contributes to the individual’s psychological well-being or happiness, code here; if quality listed in response contributes or is related to a state of independence, code “independence/independence with support.”

- Romantic relationships and/or starting a family

- Respondent talks about having a romantic relationship with a significant other

- Includes dating, marriage, children, and having his or her own family

- Physical health or safety

- Response talks about being in good health and/or physically safe

- Includes having medical insurance

- Other – parts of response that do not fit into another category

- Includes having spending money, living at home, compassionate caretakers, morality, maturity, etc.

- All of response does not answer question

- Remarks that outcome of the transition will be “no change” or simply “good”

- Any description of individual’s abilities, characteristics, or traits, including what he/she will not be able to do

- Gives opinions on the study itself, such as criticizing question wording

- Talking about things that have already happened

- Opinions about changes that need to happen in society or world that are not directly related to the transition process (i.e. “world peace,” or “we as a country need to take better care of those who can’t take care of themselves”)

References

- Arnett JJ. Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. American Psychologist. 2000;55:469–480. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnett JJ. Conceptions of the transition to adulthood: Perspectives from adolescence through midlife. Journal of Adult Development. 2001;8:133–143. [Google Scholar]

- Austin J. The role of parents as advocates for the transition rights of their disabled youth. Disabilities Studies Quarterly. 2000;20:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Billstedt E, Gillberg IC, Gillberg C. Autism after adolescence: Population-based 13- to 22-year follow-up study of 120 individuals with autism diagnosed in childhood. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2005;35:351–360. doi: 10.1007/s10803-005-3302-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Billstedt E, Gillberg IC, Gillberg C. Aspects of quality of life in adults diagnosed with autism in childhood: A population-based study. Autism. 2011;15:7–20. doi: 10.1177/1362361309346066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameto R, Levine P, Wagner M. Transition planning for students with disabilities: A special topic report of findings from the National Longitudinal Transition Study-2 (NLTS2) SRI International; Menlo Park, CA: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Carr J. The everyday life of adults with Down syndrome. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities. 2008;21:389–397. [Google Scholar]

- Eaves LC, Ho HH. Young adult outcome of autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2008;38:739–747. doi: 10.1007/s10803-007-0441-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elo S, Kyngas H. The qualitative content analysis process. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2008;62:107–115. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04569.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Everson JM, Moon MS. Transition services for young adults with severe disabilities: Defining professional and parental roles and responsibilities. Journal of the Association for Persons with Severe Handicaps. 1987;12:87–95. [Google Scholar]

- Farley MA, McMahon WM, Fombonne E, Jenson WR, Miller J, Gardner M, Coon H. Twenty-year outcome for individuals with autism and average or near-average cognitive abilities. Autism Research. 2009;2:109–118. doi: 10.1002/aur.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furstenberg FF, Raumbaut RG, Settersten RA. On the frontier of adulthood. In: Settersten RA, Furstenberg FF, Rumbaut RG, editors. On the frontier of adulthood: Theory, research, and public policy. University of Chicago Press; Chicago: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Graneheim U, Lundman B. Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: Concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Education Today. 2004;24:105–112. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2003.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halpern Quality of life as a conceptual framework for evaluating transition outcomes. Exceptional Children. 1993;59:486–498. [Google Scholar]

- Hanley-Maxwell C, Whitney-Thomas J, Pogoloff SM. The second shock: A qualitative study of parents’ perspectives and needs during their childs transition from school to adult life. Journal of the Association for Persons with Severe Handicaps. 1995;20:3–15. [Google Scholar]

- Henninger NA, Taylor JL. Outcomes in adults with autism spectrum disorders: A historical perspective. Autism. 2013;17:107–120. doi: 10.1177/1362361312441266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogan DP, Astone NM. The transition to adulthood. Annual Review of Sociology. 1986;12:109–130. [Google Scholar]

- Howlin P, Goode S, Hutton J, Rutter M. Adult outcome for children with autism. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2004;45:212–229. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00215.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh H, Shannon S. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research. 2005;15:1277–1288. doi: 10.1177/1049732305276687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivey JK. What do parents expect? A study of likelihood and importance issues for children with autism spectrum disorders. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities. 2004;19:27–33. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson DR, Stodden RA, Emanuel EJ, Luecking R, Mack M. Current challenges facing secondary education and transition services: What research tells us. Exceptional Children. 2002;68:519–531. [Google Scholar]

- Kraemer B, Blacher J. Transition for young adults with severe mental retardation: School preparation, parent expectations, and family involvement. Mental Retardation. 2001;39:423–435. doi: 10.1352/0047-6765(2001)039<0423:TFYAWS>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landis R, Koch G. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1977;33:159–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neece CL, Kraemer BR, Blacher J. Transition satisfaction and family well being among parents of young adults with severe intellectual disability. Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities. 2009;47:31–43. doi: 10.1352/2009.47:31-43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman L, Wagner M, Knokey A, Marder C, Nagle K, Shaver D, Wei X, Cameto R, Contreras E, Ferguson K, Greene S, Schwarting M. A report from the National Longitudinal Transition Study-2 (NLTS2) (NCSER 2011-3005) SRI International; Menlo Park, CA: 2011. The post-high school outcomes of young adults with disabilities up to 8 years after high school. with. [Google Scholar]

- Ruble L, Dalrymple N. An alternative view of outcome in autism. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities. 1996;11:3–14. [Google Scholar]

- Settersten RA, Ray B. What’s going on with young people today? The long and twisting path to adulthood. The Future of Children. 2011;20:19–41. doi: 10.1353/foc.0.0044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverberg SB. Parents’ well-being at their children’s transition to adolescence. In: Ryff CD, Seltzer MM, editors. The parental experience at midlife. University of Chicago Press; Chicago: 1996. pp. 215–254. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor JL. The transition out of high school and into adulthood for individuals with autism and their families. International Review of Research in Medicine and Mental Retardation. 2009;38:1–32. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor JL, Mailick MR. A longitudinal examination of 10-year change in vocational and educational activities for adults with autism spectrum disorder. Developmental Psychology. doi: 10.1037/a0034297. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor JL, Seltzer MM. Employment and post-secondary educational activities for young adults with autism spectrum disorders during the transition to adulthood. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2011;41:566–574. doi: 10.1007/s10803-010-1070-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tesch R. Qualitative research: Analysis types and software tools. Falmer; Bristol, PA: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Thorin EJ, Irvin LK. Family stress associated with transition to adulthood of young people with severe disabilities. Journal of the Association for Persons with Severe Handicaps. 1992;17:31–39. [Google Scholar]

- Whitney-Thomas J, Hanley-Maxwell C. Packing the parachute: Parents’ experiences as their children prepare to leave high school. Exceptional Children. 1996;63:75–87. [Google Scholar]