Abstract

Rumination in depression is a risk factor for longer, more intense, and harder-to-treat depressions. But there appear to be multiple types of depressive rumination – whether they all share these vulnerability mechanisms, and thus would benefit from the same types of clinical attention is unclear. In the current study, we examined neural correlates of empirically-derived dimensions of trait rumination in 35 depressed participants. These individuals and 29 never-depressed controls completed 17 self-report measures of rumination and an alternating emotion-processing/executive-control task during functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) assessment. We examined associations of regions of interest—the amygdala and other cortical regions subserving a potential role in deficient cognitive control and elaborative emotion-processing—with trait rumination. Rumination of all types was generally associated with increased sustained amygdala reactivity. When controlling for amygdala reactivity, distinct activity patterns in hippocampus were also associated with specific dimensions of rumination. We discuss the possibly utility of targeting more basic biological substrates of emotional reactivity in depressed patients who frequently ruminate.

Keywords: rumination, depression, fMRI, emotion, amygdala

Trait rumination—the tendency to engage in sustained, repetitive thinking about negative topics—is associated with depression vulnerability, severity, and chronicity, (Nolen-Hoeksema, 1991; Nolen-Hoeksema, Morrow, & Fredrickson, 1993; Spasojevic & Alloy, 2001). Yet, rumination has been defined and operationalized in many ways, with different measures of rumination reliably indexing different constructs and explaining independent variance in depressive symptoms in depressed as well as dysphoric undergraduate samples (Siegle, Moore, & Thase, 2004) as well as different temporal windows of information processing following emotional stimuli (Siegle, Steinhauer, Carter, Ramel, & Thase, 2003a). These constructs may be associated with different brain mechanisms. Understanding these differences is important if the recent emphasis on “precision medicine”, i.e., targeting specific features of disorder with treatments tuned to their biological mechanisms (Robinson, 2012) is to be met, and the promise of the National Institute of Mental Health’s emphasis on identifying biological substrates of clinically relevant phenomena (Insel et al., 2010) is to be realized.

Multiple cognitive processes have been implicated in rumination that could reflect different identifiable neural mechanisms including 1) automatic or “bottom up” attention to negative information is staple of traditional descriptions of depression (Ingram, 1984). 2) Later formulations emphasized difficulty disengaging from negative emotional information (De Lissnyder, Derakshan, De Raedt, & Koster, 2011; Joormann & Gotlib, 2008) associated with decreased recruitment of cognitive control mechanisms responsible for the regulation of attention and emotion (Joormann & Gotlib, 2008; Joormann, Levens, & Gotlib, 2011; Koster, De Lissnyder, Derakshan, & De Raedt, 2011). 3) Increased explicit elaborative emotional processesing has also been considered, e.g., subserving appraisal (Mathews & MacLeod, 2005; Moberly & Watkins, 2008). Such processes also appear to interfere with subsequent non-emotional cognition (Kensinger & Corkin, 2003), particularly in the context of clinical depression (Fales et al., 2008). Whether the later dimensions of decreased cognitive control and explicit elaborative emotional information processing add explanatory power above and beyond powerfully conditioned automatic emotional processing, from the perspective of mechanistic targets, is specifically unclear.

In the present study, we related multiple rumination constructs, derived from many self-report measures, to likely neural substrates of these three mechanisms. This approach is in contrast to previous neuroimaging studies, among which there is considerable differentiation in results, which have generally assessed only one kind of trait rumination (Johnson, Nolen-Hoeksema, Mitchell, & Levin, 2009; Thomas et al., 2011), or compared two specific subtypes of rumination but not attempted to span the space of rumination-like constructs (e.g., analytical vs. angry rumination; Fabiansson, Denson, Moulds, Grisham, & Schira, 2012). It complements our previous study showing that different types of rumination are related to different temporal windows of emotional information processing assessed using psychophysiology (Siegle, et al., 2003a). We also believed this approach to be warranted as initial investigations have found differences between neural features of maladaptive emotion-focused rumination (i.e., brooding) and seemingly less maladaptive modes of self-focus (i.e., reflection) (Hamilton et al., 2011; Kühn, Vanderhasselt, De Raedt, & Gallinat, 2012; Vanderhasselt, Kühn, & De Raedt, 2011).

We focused on activity in the amygdala as a potential neural indicator of automatic emotional information processing. The amygdala consists of a phylogenetically early collection of nuclei in the temporal lobes associated with the automatic detection of salient emotional features in the environment (Bishop, Duncan, & Lawrence, 2004; LeDoux, 1996). Together with a larger network of brain regions, the amygdala plays a key role in emotional information-processing, as well as the generation of negative mood states (Bishop, et al., 2004; LeDoux, 1996). Increased and sustained amygdala reactivity has been observed in response to negative stimuli in depression, particularly depressed ruminators (Siegle, Steinhauer, Thase, Stenger, & Carter, 2002b), as well as during rumination (Denson, Pedersen, Ronquillo, & Nandy, 2009; Ray et al., 2005). Given its crucial role in coordinating and sustaining responses to threat (LeDoux, 1996), sustained “hijacking” of attention by bottom-up reactivity in the amygdala could be associated with depressed ruminators’ tendency to continue thinking about negative topics they find particularly threatening.

We examined whether there were types of rumination for which other neural mechanisms that have been suggested to modulate amygdala activity added explanatory power above and beyond this automatic reactivity. In particular, depression-related deficits in cognitive control have been associated with decreased reactivity in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (dlPFC) following emotional stimuli (Fales, et al., 2008; Siegle, Steinhauer, Thase, Stenger, & Carter, 2002a; Siegle, Thompson, Carter, Steinhauer, & Thase, 2007a). In healthy individuals, the dlPFC has been implicated in cognitive control and may additionally contribute to emotion regulation by initiating top-down inhibition of the amygdala and regions associated with early emotional information processing (Davidson, 2000; Drevets & Raichle, 1998; Mayberg et al., 1999; Ochsner, Bunge, Gross, & Gabrieli, 2002; Ochsner et al., 2004). Whether rumination is a function of decreased prefrontal control above and beyond increased reciprocal inhibition from areas such as the amygdala (Arnsten, 2009; Bishop, 2007; Porrino, Crane, & Goldman-Rakic, 1981), though, is unclear. The same may be said for more ventromedial prefrontal regions that also receive inhibitory inputs from the amygdala and appear to be associated with modulation of semantic representations of emotional information (Buhle et al., 2013; Phillips, Ladouceur, & Drevets, 2008a). The subgenual cingulate cortex is implicated in monitoring of emotional reactivity and, at times, the up-regulation of negative affect (Hamilton, Glover, Hsu, Johnson, & Gotlib, 2011; Phillips, Ladouceur, & Drevets, 2008b); its hyperreactivity in depressed individuals appears to block recovery in response to clinical treatments (Mayberg et al., 2005; Siegle et al., 2012) and thus may be a strong candidate for explaining variance in rumination above and beyond amygdala activity. Studies on the neural correlates of rumination have provided inconsistent accounts of the roles these regions play in ruminative thinking (Cooney, Joormann, Eugene, Dennis, & Gotlib, 2010; Johnstone, van Reekum, Urry, Kalin, & Davidson, 2007; Siegle, et al., 2006; Siegle, et al., 2007b; Vanderhasselt, Kuhn, & De Raedt, 2011), possibly because they use different formulations for rumination and different aspects of explicit recruitment of cognitive control.

Trait rumination, variously defined, has also been associated with individual differences in activation of mechanisms associated with more explicit elaboration on negative emotional material including the anterior insula, medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC), poster cingulate cortex (PCC), and hippocampus during the processing of negative emotional stimuli (Denson, et al., 2009; Johnson, et al., 2009; Ray, et al., 2005; Thomas, et al., 2011). For example, the anterior insula plays a central role in interoceptive self-focus and helps to integrate bodily cues during the appraisal of negative environmental stimuli (Paulus & Stein, 2006). The mPFC, PCC, and bilateral hippocampus also contribute to emotional appraisals through internal representations of self-referent information and autobiographical memory (Fortin, Agster, & Eichenbaum, 2002; Gusnard, Akbudak, Shulman, & Raichle, 2001; Johnson et al., 2006). Depressed participants show greater activation than controls in these areas during experimentally-induced rumination (Cooney, et al., 2010); however, they also show increased activation of the amygdala. We therefore examined whether associations between rumination and activation of these regions to negative stimuli were independent of amygdala hyper-reactivity.

We accounted for a variety of formulations of rumination (Siegle, et al., 2004) including various questionnaires that assess the frequency of thoughts about one’s depressive symptoms (Nolen-Hoeksema, et al., 1993), the quality and intrusiveness of thoughts about recent stressful events (Fritz, 1999; Horowitz, Wilner, & Alvarez, 1979), emotional and cognitive responses to personal goal failure (Scott & McIntosh, 1999), and metacognitive reactions to one’s own negative thoughts and emotions (Papageorgiou & Wells, 1999; Roger & Najarian, 1989). This distinction is particularly critical as there is evidence from the behavioral literature that different kinds or rumination may be associated with different abnormalities in emotion-processing and cognitive control (De Lissnyder, et al., 2011; Whitmer & Banich, 2007).

Thus, we used functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to assess whether empirically-derived dimensions of trait rumination were associated with brain activity in the abovementioned brain regions in a depressed sample (Siegle, et al., 2011). We used a task that alternated between emotional (e,g., labeling the valence of emotional words) and non-emotional stimuli (e.g., digit-sorting). For emotion-labeling, in order to draw participants’ attention to the emotional content while engaging minimal cognitive resources, we deliberately simplified the task to require a single button press for the identification of positive, negative, or neutral words. Our objective was to specifically allow investigation of the degree to which different types of rumination are characterized by prolonged emotion-processing in response to negative stimuli that last beyond the stimulus duration, i.e., long after the offset of an apparent threat, for which bottom-up resources should be recruited. Furthermore, while labeling emotions can be used by some individuals as a way of decreasing reactivity, utilizing this design may actually help uncover differential biases towards or away from the sustained processing of emotional material. We specifically accounted for possible differences in dynamic and sustained activity in these systems in association with different aspects of rumination by analyzing the temporal dynamics of their reactivity throughout each 27-second trial. This approach allowed detection of whether temporally-bound task features such as switching attention from negative stimuli to non-emotional cognitive processing were specifically associated with activity in regions subserving cognitive function above and beyond amygdala activity. Of note, we did not attempt to either elicit or capture activity associated with the actual process of ruminating occurring during fMRI scanning. Rather, our task allowed us to examine associations between the dispositional tendency to ruminate and individual differences in a variety of ongoing processes that could potentially underlie perseverative emotion-processing.

Given previously reported amygdala-rumination associations, we hypothesized that increased and sustained amygdala activation would be positively associated with multiple dimensions of rumination. We further hypothesized that trait rumination would be independently negatively associated with activation in areas associated with cognitive control such as the dlPFC, particularly during the cognitive portion of the task. We had no directional hypotheses for other prefrontal regions (e.g., rostral (BA24) and subgenual (BA25) cingulate), as literature associates them with all of regulating, monitoring, and facilitating negative emotion-processing. However, given these functions we did predict they would explain additional variance above and beyond the amygdala and dlPFC, particularly during the task-switch portion of the task. Similarly we predicted that areas associated with elaborative emotional processing such as appraisal (e.g., the hippocampus, anterior insula, mPFC, and PCC) would positively explain additional variance in rumination. That said, as the alternating task we used was not designed to explicitly probe functions most closely associated with these brain regions (namely self-referential processing and autobiographical memory), we do not suggest that examination of these regions is a definitive test of their role in all situations involving rumination.

Methods

Participants

Participants were 35 adults with a current principal diagnosis of major depressive disorder (MDD) via the Structured Clinical Interview for the DSM–IV (First, Spitzer, Gibbon, & Williams, 1996). A group of 29 healthy control participants also completed the fMRI protocol, providing data for qualitative comparison with depressed subjects. (See Table 1 for descriptive characteristics.) All participants reported good physical health, no antidepressant use within two weeks of testing (six weeks for fluoxetine), and no psychoactive drug abuse within six months. Additional exclusion criteria for all participants included a history of psychosis or manic-depressive illness, and a verbal IQ < 80 (Nelson & Willison, 1991). All depressed participants reported no excessive alcohol use in the past 6 months. We have previously reported on associations of fMRI with depression and treatment response in subsets of these patients (Siegle, et al., 2007b) but not with regard to a careful analysis of rumination.

Table 1.

Subject Demographic and Behavioral Data

| Measure | Depressed | Controls | Significant Difference |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 35 | 29 | |

| Male, n | 14 | 12 | ns |

| Caucasian, n | 26 | 20 | ns |

| Age, M(SD) | 39.2 (12.3) | 33.1 (10.1) | t(62) = −2.18, p = .03 |

| Years Education, M(SD) | 14.8 (2.2) | 15.5 (1.8) | ns |

| NAART VIQ Equivalent | 111.0 (7.4) | 109.7 (8.3) | ns |

| BDI, M(SD) | 29.3 (11.2) | 4.0 (4.6) | t(46.8) = −12.2, p<.001 |

| Median No. Depressive Episodes | 5 or more | 0 | n/a |

| Post-Scan Ratings of Negative Words (1 = very negative and 7 = very positive) | 2.1 (.64) | 2.1 (.50) | ns |

| Reaction Times on VID, M(SD) | 1375 (519) | 1040(294) | t(51.8)= −3.08,p=.002 |

| Negative Word Identification % Correct | .93 (.11) | .90 (.16) | ns |

| Digit Sorting Percent Correct | .93 (.08) | .90 (.16) | ns |

Procedure

Participants attended three appointments within three weeks: 1) signing IRB-approved consent forms, completing a SCID, and vision test; 2) tasks during psychophysiological assessment and the rumination questionnaires; 3) the same tasks during fMRI assessment. A digit-sorting task was administered first to avoid confounding by previous emotional responsivity, followed by other tasks in counterbalanced order; only one of these tasks, involving alternating valence identification and digit sorting trials, is reported here.1

Construction of composite rumination scores from self-report questionnaires

We administered 17 subscales from 10 different self-report measures to depressed patients. The battery of measures was designed to sample multiple aspects of perseverative negative thought corresponding to the three sub-processes constructs described in the introduction (emotional reactivity, regulatory control, etc). These measures, their internal consistency, and their characteristics in the current sample are listed in Table 2 and are described in greater detail in our published review of this battery (Siegle, et al., 2004). Participants also completed a measure of depressive severity (Beck Depression Inventory II; Beck, Steer, & Brown, 1996), which was used in subsequent analyses controlling for the effects of depression on rumination.

Table 2.

Rumination Subscales, Internal Consistency, and ICA Factor Loadings

| Scale | Full name | IC | MDD Mean (SD) | HC Mean (SD) | Components | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (Experiential) | 2 (Event-related) | 3 (Constructive) | |||||

| ECQ-REH | Emotion Control Questionnaire - rehearsal | α = .75 | 8.3 (3.5) | 3.4 (1.7) | 0.807 | 0.338 | -0.043 |

| MRQ-EMOTS | Multidimensional Rumination Questionnaire - emotion-focused | α = .94 | 27.3 (9.8) | 13.9 (7.3) | 0.057 | 0.748 | 0.409 |

| MRQ-SRCH | Multidimensional Rumination Questionnaire - searching for meaning | α =.84 | 12.7 (5.4) | 7.5 (3.1) | 0.208 | 0.342 | 0.656 |

| MRQ-INST | Multidimensional Rumination Questionnaire - instrumental rumination | α = .89 | 16.4 (6.1) | 11.2 (6.4) | −0.176 | 0.475 | 0.64 |

| RIES-INT | Revised Impact of Event Scale - intrusiveness | α = .90 | 19.5 (6.0) | 13.5 (6.0) | 0.253 | 0.785 | 0.002 |

| RNE-GEN | Rumination on a Negative Event - general rumination | α = .80 | 24.0 (8.1) | 11.7 (9.9) | −0.35 | 0.645 | 0.135 |

| RNT-EMOT | Rumination on Negative Thoughts - emotion-focused rumination | α = .90 | 654 (291) | 269 (184) | 0.358 | −0.235 | −0.058 |

| ROS | Rumination on Sadness | α = .90 | 40.3 (11.0) | 22.0 (7.6) | 0.673 | 0.506 | 0.077 |

| RRQ-RUM | Rumination Reflection Scale - rumination | α = .88 | 47.3 (8.0) | 28.8 (8.0) | 0.825 | 0.253 | 0.009 |

| RRQ-REF | Rumination Reflection Scale - reflection | α = .89 | 37.7 (9.9) | 38.7 (12.7) | −0.034 | 0.06 | 0.568 |

| RSQ-RUM | Rumination Styles Questionnaire –rumination | α = .89 | 57.2 (11.8) | 34.0 (8.9) | 0.609 | 0.557 | 0.067 |

| SMRI-EMOT | Scott Macintosh Rumination Inventory - emotionality | α = .61 | 15.0 (4.0) | 9.1 (4.2) | 0.657 | −0.028 | 0.017 |

| SMRI-MOT | Scott Macintosh Rumination Inventory -motivation | α = .88 | 9.9 (4.7) | 17.1 (3.6) | 0.13 | −0.142 | 0.604 |

| TCQ-WORRY | Thought Control Questionnaire - worry | α =.77 | 11.4 (3.1) | 8.5 (2.3) | 0.675 | 0.038 | 0.24 |

| TCQ-PUN | Thought Control Questionnaire - punish | α =.75 | 10.0 (3.4) | 8.3 (1.8) | 0.721 | 0.005 | 0.488 |

| TCQ-REAPP | Thought Control Questionnaire - re-appraisal | α =.69 | 12.6 (3.4) | 15.4 (3.0) | 0.06 | 0.247 | 0.781 |

| TCQ-SOC | Thought Control Questionnaire - social control | α =.79 | 10.6 (3.3) | 15.16 (4.0) | −0.33 | 0.142 | 0.247 |

| Variance explained (%) | 23.3 | 16.7 | 15.9 | ||||

Note: Specific factor loadings >.4 are shown in bold text.

MDD = Depressed participants; HC = Healthy control participants; IC = Internal consistency

To identify underlying dimensions responsible for covariation among rumination measures, we factor-analyzed depressed participants’ scores on all subscales. Principal components analysis with varimax rotation (retaining factors above the knee of a Scree plot) yielded three factors that explained 56% of the variance and appeared to reflect distinct dimensions of rumination (see Table 2). The first factor accounted for 23% of the variance and, based on its highest-loading subscales, appeared to represent repetitive focus on and reactivity to negative aspects of the self, negative emotions, and current depressive symptoms. We will henceforth refer to it as “Experiential Rumination”. The second factor accounted for 17% of variance and uniquely included measures assessing the frequency and intrusiveness of thoughts about specific negative events. This factor, henceforth “Event-related rumination”, included some subscales that also loaded highly on the first factor and assessed emotion-focused rumination. The third factor, accounting for 16% of variance, appeared to measure the tendency to engage in various types of adaptive or non-negative repetitive cognition, henceforth “Constructive Rumination”.

fMRI task: Alternating Emotion-Processing and Cognitive Control

The task contained 60 trials of alternating emotion-identification and digit-sorting. On emotion-identification trials, “What’s the emotion” was displayed (1 s), followed by a fixation mask (row of X’s; 2 s), followed by a word (from the previously described set; 200 ms), followed by a mask (7.5 s). Participants were instructed to name the emotionality of each word by pushing buttons for “Positive”, “Negative”, or “Neutral” as quickly and accurately as they could after the word appeared. Next, the cue “Order the numbers” (1 s) signaled the beginning of a digit-sorting trial. Following a fixation mask (1 s), participants viewed a string of five digits (2 s), followed by another mask (5 s). Then, a new “target” digit from the previously presented set appeared (10 s). Participants were told that when the string of digits appeared, they should read them from left to right, put them in numerical order in memory, and remember the middle digit in the sorted list. When the target appeared, they were to push a “yes” or “no” button indicating whether the target was the middle digit from the previous list, as quickly and accurately as they could.

Stimuli for emotion-identification trials consisted of sixty emotion adjectives, including 30 normed and 30 participant-generated words. Normed words consisted of 10 positive, 10 negative, and 10 neutral words chosen using a computer program (Siegle, 1994). The program was designed to create affective word lists from the Affective Norms for English Words (ANEW) (Bradley & Lang, 1997) master list, with stimuli that were balanced for normed affect, word frequency, and word length. To obtain personally-relevant stimuli, participants were asked to generate words between three and 11 letters long prior to testing. Participants were instructed to generate “10 personally relevant negative words that best represent what you think about when you are upset, down, or depressed,” as well as “10 personally relevant positive words that best represent what you think about when you are happy or in a good mood,” and “10 personally relevant neutral (i.e., not positive or negative) words that best represent what you think about when you are neither very happy nor very upset, down, or depressed.” Because the present study focused on negative information-processing in rumination, we specifically examined participants’ responses to negative stimuli on the 20 trials that contained negative emotional words (10 normed and 10 participant-generated).

This task was one of several computer-based tasks completed by participants during fMRI scanning. Other tasks from this battery are described elsewhere, along with their relationship to depressive symptoms and therapeutic outcome in a subsequent clinical trial (Siegle, et al., 2006; Siegle, et al., 2011; Siegle, Steinhauer, Stenger, Konecky, & Carter, 2003b; Siegle, et al., 2007b; Thompson & Siegle, 2009b).

fMRI Apparatus

Thirty-four or 30 3.2mm slices were acquired parallel to the AC-PC line using a reverse spiral pulse sequence (3T GE scanner, T2*-weighted images depicting BOLD contrast; TR=1500ms, TE=5ms, FOV=24cm, flip=60), yielding 18 whole-brain images per 27-second trial. The change from 34 slices (22 controls, 15 depressed) to 30 slices (7 controls, 20 depressed) was to reduce scanner overheating, and had no discernable effects on the obtained signal. Stimuli were displayed in black on a white background via a back-projection screen (.88° visual angle). Responses were recorded using a Psychology Software Tools™ glove with millisecond resolution. Labels for behavioral responses were displayed on screen throughout the task (e.g., for VID: “+N-“ representing “Positive” on the index finger, “Neutral” on the middle finger, and “Negative” on the ring finger; for DS: “YN” representing “Yes” on the index finger and “No” on the ring finger). Mappings of glove buttons to responses were counterbalanced across participants.

Data Selection and Cleaning

Harmonic means of reaction times (Ratcliff, 1993) were calculated within subjects for each condition. Outliers >Tukey Hinges+/−1.5*IQR were replaced with Tukey Hinges+/−1.5*IQR. Functional MRI analyses were conducted via locally-developed NeuroImaging Software (NIS) and AFNI (Cox, 1996). Following motion correction using the 6 parameter AIR algorithm (Woods et al 1993), linear trends within runs were removed to eliminate effects of scanner drift. Outliers>Tukey Hinges+/−2.2IQR were replaced with Tukey Hinges+/−2.2IQR. Imaging data were temporally smoothed (five-point middle-peaked filter), cross-registered to a reference brain using the 12 parameter AIR algorithm, and spatially smoothed (6mm FWHM).

Our regions of interest included anatomically-defined bilateral amygdala, hippocampus, and anterior insula, and single midline masks of BA25/subgenual cingulate, BA24/ventromedial PFC, BA10 in the medial frontal gyrus, and the posterior cingulate cortex. In addition, the left and right dlPFC have been shown to be functionally heterogeneous regions, with certain portions corresponding to more cognitive functions while others appear to subserve more emotion-regulatory functions. However, the exact spatial locations of these different subsections are not yet well delineated. Thus, for analyses focused on the dlPFC, we specified two sets of ROI masks. First, in order to represent a region reflecting overlapping cognitive control and emotion regulation abnormalities in depression, we included a functionally-defined mask of the left dlPFC shown to have decreased reactivity on a cognitive task (e.g., digit-sorting) in depressed compared to control participants that also demonstrates decreased reactivity on an emotional task (e.g., personal relevance rating of emotional words) (Siegle, et al., 2007a). Second, to capture potentially broader associations between rumination and dlPFC function, we considered bilateral anatomical dlPFC (lateral BA9/46) regions. All ROI definition criteria are described in Supplement I. For each ROI, time-course activations from negative-word trials was extracted and averaged at each of the task’s 18 scans. BOLD-% signal change was then calculated by subtracting activation at the first scan from activation at each of the subsequent scans (scans beginning 1.5–27 seconds after cue onset). This produced a total of 17 scans of useful imaging data (7 valence identification and 10 digit-sorting). All correlation and regression analyses in the present study were performed using neural activation values quantified in this way. Timeseries results are reported in scans (e.g., TR’s), as these were the units of analysis that were used to calculate our statistics.

Here, we were interested specifically in associations of rumination with neural reactivity to negative stimuli. We did not subtract a baseline condition (e.g., neutral word trials) from reactions to negative words because 1) depressed individuals tend to interpret apparently neutral stimuli such as words and faces as more negative than do controls (e.g., Lawson, MacLeod, & Hammond, 2002; Leppänen, Milders, Bell, Terriere, & Hietanen, 2004)making them a false “baseline” and 2) subtraction of neutral timecourse data at each scan of the time series could differentially alter the direction and magnitude of raw activation values, which would complicate the interpretation of correlations with rumination.

Data Analyses

Primary correlation analyses used only depressed participants’ BOLD responses. Analyses 1) tested for associations between rumination and the time-course of amygdala reactivity and 2) identified which a priori regions might serve as secondary explanatory variables in subsequent regression analyses. For each region, we correlated activation at each scan with each of the three rumination factor scores. We were careful regarding accounting for time as we have previously shown that different temporal windows of information processing are differentially related to different types of rumination (Siegle, et al., 2003a). Because our task required participants to alternate between emotional valence identification (scans 2–9) and digit-sorting (scans 10–18), we examined these temporal periods separately for evidence of significant correlations. To control for Type I error, correlations were subjected to temporal contiguity thresholds (procedure described in Supplement II). In short, because we were primarily interested in sustained processes underlying rumination, we were less interested in the peak activity of any one scan at any one time point and we instead focused on elevations in activation that persisted for a significantly long duration. Towards that end we followed Guthrie and Buchwald’s (Guthrie & Buchwald, 1991) procedure to determine that a set of three consecutive scans (4.5s) each significant at p<.1 yielded an interval that was significant at p<.05. Under this formulation no single scan was interpreted, but rather, intervals significant at p<.05 are reported on. This method of temporal contiguity thresholding allows for the control of type I error inflation by taking into account the high level of scan-to-scan autocorrelation commonly found in fMRI timeseries data.

To test whether activation in a priori prefrontal and additional appraisal-related ROIs explained significant variance in rumination independently of amygdala activation, we ran separate hierarchical regression models for each rumination factor. We entered amygdala activation at step 1 and secondary regions together at step 2, using mean activation values from the temporal windows identified by correlation analyses. As bilateral regions such as the right and left amygdala tend sometimes show coordinated activation patters, we attempted to control for multicollinearity effects by identifying correlated regions to be entered on the same step and removing redundant variables from the analysis. This prevented us from underestimating the relative contribution of significantly correlated ROIs in a small sample, and resulted in a total of four separate regression analyses.

Sensitivity analyses: controlling for depressive severity and functional connectivity

Depressive symptoms overlap significantly with some kinds of rumination (Siegle, et al., 2004). To determine whether neural activation accounted for significance variance in rumination when controlling for depressive severity, we ran hierarchical regression models with BDI scores entered at step 1 and all regions from the original models entered at step 2.

Trait rumination has also been linked to functional connectivity, the degree to which activation is temporally coordinated among individual ROIs (e.g., Berman et al., 2011). Because connectivity between two regions (e.g., the amygdala and the hippocampus) might explain addition variance in rumination above and beyond the activation of each individual region, we augmented our original regression models (e.g., with ROIs entered at steps 1 and 2) by adding connectivity values on a third step for connectivities with significant bivariate correlations with rumination factor scores. Functional connectivity between pairs of regions was quantified using functional canonical correlation or FCC (e.g., He, Muller, & Wang, 2004; Ramsay & Silverman, 2005). This method quantifies relationships between the shape of waveforms representing activation in response to stimuli across regions (Zhou, Thompson, & Siegle, 2009). It is therefore particularly appropriate for examining associations relevant to sustained reactivity where the temporal windows of interest are not known in advance and, where directionalities of correlations might change across the time-course of a response (Thompson & Siegle, 2009a). We have used this method to successfully identify decreased associations between the amygdala and other prefrontal regions in this study on another task in many of the same participants (Siegle, et al., 2007b).

Results

Behavioral Results

Participants preformed with high accuracy on both valence identification (VID) and digit-sorting (DS), with depressed and control participants showing comparable accuracy rates (see Table 1). Depressed participants identified negative words more slowly than controls, however no significant group effects were found for post-scan ratings of negative words.

Within the depressed sample, correlation analyses revealed no significant associations between Experiential or Event-related rumination and decisions on VID. However, Constructive rumination was positively associated with identification of negative words as negative (r = .46, p = .007) and neutral words as neutral (r = .40, p = .02). Rumination was uncorrelated with DS accuracy, largely because performance was, by design, at ceiling for most participants. No significant associations were found between rumination and response latencies to emotional words (all p’s > .7).

fMRI Results

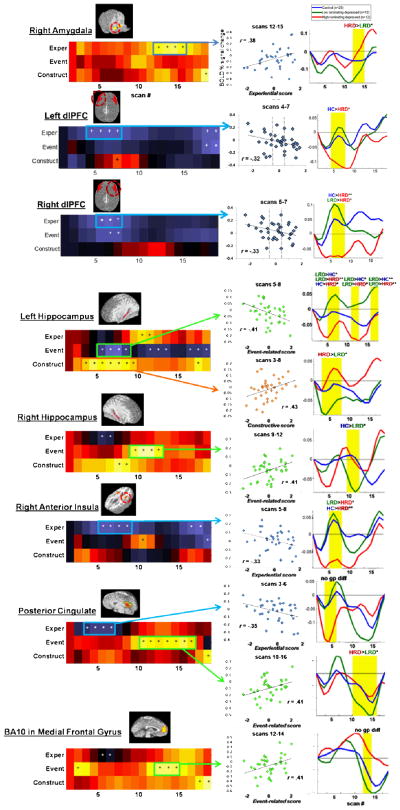

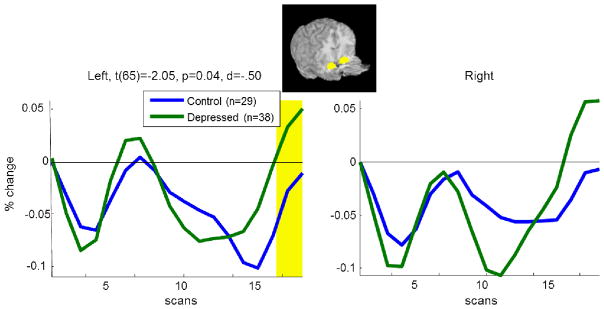

A preliminary comparison of depressed and healthy control participants’ amygdala activation (Figure 1) revealed that, as in previous similar studies (Siegle, et al., 2002a; Siegle, et al., 2007b), depressed participants had greater sustained left amygdala activity at the very end of the digit sorting period, scan 17, t(65)= −2.05, p=.04. This weak but suggestive result justified looking for whether sustained amygdala activity might be moderated by a third variable – rumination was a good candidate given our previous work. Three depressed participants from this analysis were subsequently excluded from correlation/regression analysis because of missing data for multiple rumination measures.

Figure 1. Mean BOLD % signal change in the bilateral amygdala in response to negative words for depressed participants and a group of healthy controls.

Highlighted temporal regions denote a significant group difference at p<.05.

Associations between neural activation and empirical dimensions of rumination

Figure 2 shows correlations between depressed participants’ rumination scores and left amygdala activation. Correlation magnitudes are represented by color at each scan. For illustrative purposes, individual rumination subscale correlations are shown on the left (Fig. 2A), with factor-analytically derived composite scores below (Figure 2B). Scatterplots show participants’ data from significant correlation periods (Fig. 2C, E, G). To illustrate relevant neural activation patterns for possibly clinically relevant high- and low-ruminating subgroups, %-signal change is plotted separately for depressed participants scoring in the top third (“High Ruminators” or “HRD”) and bottom third (“Low Ruminators” or “LRD”) for each factor (Fig. 2D, F, H), along with data from a group of healthy control participants. Group differences in mean activation at each significant correlation window are noted above each plot; statistics for these analyses are reported in Supplement III; note that these subgroup-graphs are illustrative of clinical phenomenon, rather than fully-powered analyses. Similarly, because these graphs are intended to be illustrative and are not part of our primary analyses, we did not take additional steps to control for multiple comparisons. Figure 3 shows analogous plots for the right amygdala and other regions in which we found significant correlations with rumination.

Figure 2.

Associations of trait rumination with early and sustained BOLD activity in the left amygdala during alternating emotion processing/cognitive distracter task.

Note: Color maps represent correlation matrices for correlations of each rumination measure (Figure 2A) or factor (Figure 2B) with BOLD % signal change across 17 scans (scan 1 = baseline). In Figure 2B, asterisks (*) denote scans at which correlation values were significant at p <. 05 and plusses (+) denote scans significant at p < .1. Scatterplots (C, E, and G) show the relationship between depressed subjects’ rumination factor scores and mean activation at significant temporal windows. Dotted vertical lines denote cutoff scores splitting the sample into thirds, to the left and right of which depressed subjects were classified as low- or high-ruminators on that factor. The graphs on the right (D, F, and G) illustrate BOLD % signal change for high-ruminating depressed (N=12), low-ruminating depressed (N=12), and healthy control subjects (N=29). Vertical yellow bars denote temporal windows in which significant correlations were found. T-tests were performed to test for significant differences between each group’s mean activation during these windows. The text above each yellow window indicates whether groups differed in mean activity. * = trend (p < .1), ** = p < .05. HRD = high-ruminating depressed, LRD = low-ruminating depressed, HC = healthy controls. Statistics for group comparisons can be found in Supplement III.

Figure 3.

Graphs as in Figure 2 for other regions including the right amygdala, right and left anatomical dlPFC, hippocampus, insula, posterior cingulate, and BA10 in the medial frontal gyrus.

Correlations between amygdala reactivity and trait rumination

All three rumination factors were correlated with sustained amygdala activation in depressed participants (Fig. 2B, Fig. 3, Table 3 [column 4]). Experiential rumination was positively correlated with left and right amygdala activation during DS. Event-related rumination was positively correlated with sustained left amygdala activation following the completion of DS, and, unexpectedly, negatively correlated with left amygdala activation during VID. The strongest and most sustained correlations we found were with Constructive rumination, which was positively correlated with both left amygdala activity throughout VID and DS.

Table 3.

Hierarchical Multiple Regression Analyses Explaining Trait Rumination Factor Scores with Amygdala and Other Correlated Regions of Interest

| Regions of Interest | Time window (scans) | Rumination zero-order r | Model 1 | Model 2 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| R2 | p | R2Δ | P | sr2 | p | |||

| Factor 1: Experiential Rumination

| ||||||||

| Left Amyg | 11–15 | .36 | .13 | .04* | .10 | .05 | ||

| L dlPFC | 4–7 | −.32 | .14 | .26 | .01 | .48 | ||

| R dlPFC | 5–7 | −.33 | .00 | .97 | ||||

| Post Cing | 3–6 | −.33 | .01 | .51 | ||||

| R Ant Insula

|

5–8 | −.35 | .03 | .29 | ||||

| R Amyg | 12–15 | .38 | .15 | .02* | .12 | .04* | ||

| L dlPFC | 4–7 | −.32 | .14 | .26 | .00 | .98 | ||

| R dlPFC | 5–7 | −.33 | .01 | .57 | ||||

| Post Cing | 3–6 | −.33 | .01 | .46 | ||||

| R Ant Insula | 5–8 | −.35 | .00 | .69 | ||||

|

| ||||||||

| Factor 2: Event-related Rumination | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Left Amyg | 5–7 | −.35 | .28 | .006** | .02 | .25 | ||

| 16–18 | .40 | .04 | .09 | |||||

| Left Hippo | 5–8 | −.41 | .36 | .005** | .02 | .25 | ||

| 11–13 | −.30 | .07 | .04* | |||||

| 16–18 | −.32 | .002 | .70 | |||||

| Right Hippo | 9–12 | .41 | .12 | .008** | ||||

| BA10/MFG | 12–14 | .36 | .000 | .87 | ||||

| Post Cing | 10–16 | .34 | .02 | .21 | ||||

|

| ||||||||

| Factor 3: Constructive Rumination | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Left Amyg | 9–17 | .39 | .16 | .02* | .08 | .07 | ||

| Left Hippo | 3–8 | .43 | .11 | .04* | .11 | .04* | ||

Note:

p < .05,

p < .01

Across all rumination factors, participants with the highest rumination scores showed greater sustained reactivity than either low ruminators or controls, although group differences were not always statistically significant (Figs. 2 and 3; Supplement III). One exception included left amygdala activation during the VID task, in which depressed low-ruminators unexpectedly had significantly greater reactivity than high-ruminators and controls, while high-ruminators did not differ from controls.

Identification of correlations in additional a priori regions

No significant correlation windows were observed in the empirically-defined left dlPFC, BA24/vmPFC, BA25/sgACC, or the left anterior insula. We therefore did not specify any models containing these ROIs in our primary regression analyses.

Multiple regions had negative zero-order correlations with Experiential rumination during VID, including the anterior insula, PCC, and anatomical right and left dlPFC. For this factor, high-ruminators had greater deactivations than low-ruminators and controls in all four of these regions.

Event-related rumination was negatively correlated with left hippocampus activation during VID and DS, with low-ruminators showing greater reactivity than high-ruminators and controls. Event-related rumination was positively correlated with activation during DS in the right hippocampus, BA10/MFG, and PCC. Low-ruminators showed greater right hippocampal deactivation than controls in the hippocampus, and greater PCC deactivation than high-ruminators. No other group differences were observed.

Finally, Constructive rumination was positively correlated with left hippocampal activation during VID. High Constructive had higher activation than low-ruminators, however neither group deviated significantly from controls.

Examining whether other regions account for variation in trait rumination above and beyond amygdala activity

We used hierarchical regression analyses to examine which variables of the correlated secondary regions were useful in explaining individual differences in each dimension of trait rumination after accounting for amygdala activation. Results are shown in Table 3.

Experiential rumination (Factor 1)

Activation during periods of significant correlation in the left and right amygdala (scans 11–15 and 12–15 respectively) were significantly intercorrelated (r = .67, p <.001), and therefore separate models were run for each. The right amygdala explained 15% of the variance in rumination. Together all other regions explained an additional 14% of the variance in rumination which was not significant (p = .26), and only the amygdala explained significant independent variance at step 2 (left amygdala: sr2 = .12, p = .03; right amygdala: sr2 = .14, p = .02); however, there was strong collinearity among the regressors entered at the second step (.36 < r < .70, all p < .05). To probe the extent to which failure to detect additional relationships were a function of this collinearity, additional variance explained by each of the regions entered separately was considered. All regions explained between 5 and 10% additional variance with the anterior insula and posterior cingulate explaining significant variance in the model alone with the amygdala (ΔR2’s > .10, p’s < .05) and the right DLPFC having a similar effect size (ΔR2 = .09, p = .06).

Event-related rumination (Factor 2)

The two windows of left amygdala activation identified in correlation analyses (scans 5–7 and scans 16–18) were uncorrelated with one another and were therefore entered together at step 1. Adding activation windows for the left hippocampus (scans 5–8, 11–13, and 16–18), right hippocampus (scans 9–12), BA10/MFG (scans 12–14), and PCC (scans 10–16) at step 2 resulted in a significant increase in variance explained (ΔR2 = .36, p < .001). Individually, only windows of right and left hippocampal activation explained significant independent variance at step 2 (right hippocampus: sr2 = .12, p = .008; left hippocampus, scans 11–13: sr2 = .07, p = .04). The negatively-correlated window of left amygdala activation (scans 5–7) did not explain significant independent variance after adding these additional regions (sr2 = .02, p = .25), while sustained amygdala activation (scans 16–18) explained only marginally significant independent variance (sr2 = .04, p = .09).

Constructive rumination (Factor 3)

The two windows of left amygdala activation identified in correlation analyses (scans 2–5 and 9–17) were significantly correlated with one another (r = .45, p = .006). To maintain uniformity with the other models we ran, and because we were primarily interested in sustained amygdala activation, we entered the later window (scans 9–17) for the model shown in Table 3. An alternate model with the earlier window at step 1 can be found in Supplement V. Adding left hippocampal activation (scans 3–8) led to a significant increase in variance explained (ΔR2 = .11, p = .04), with the hippocampus explaining significant independent variance (sr2 = .02, p = .25) and the amygdala dropping to marginal significance (sr2 = .08, p = .07). Results from the supplementary analysis indicated no significant increase in variance explained when the hippocampus was added to the earlier amygdala window (ΔR2=.02, p=.97).

Sensitivity Analyses

Controlling for depressive severity

To control for the role of depressive severity, we ran additional hierarchical regressions with BDI scores entered at step 1 and neural activation at step 2. As shown in Supplement IV, neural activation explained additional variance above and beyond BDI for Event-related and Constructive rumination models. For Experiential rumination, no significant changes was observed for the overall models at step 2; however the left and right amygdala did continue to explain significant independent variance at this step.

Accounting for connectivity

For all four models originally listed in Table 3, we used the same strategy as for selecting regions, first considering connectivities with significant bivariate relationships to rumination, and then examining whether 1) they explained additional variance in rumination above and beyond activity and 2) whether activities in the model still explained variance when connectivities were included. Supplemental Table VI shows that for Experiential rumination, regional correlations with the Insula and anatomical DLPFC were significant but did not add significant variance above and beyond activity data (ΔR2=.11, p=.11); the magnitude of semipartial correlations with activities did not change appreciably. For event-related rumination, none of the connectivities calculated were significantly correlated with rumination (all p’s > .24), and therefore additional model was specified for this factor. For Constructive rumination, functional connectivity between the left amygdala and left hippocampus was negatively correlated with rumination (r = −.36, p = .03), however adding connectivity values between these two regions at step 3 resulted in non-significant changes in variance explained in rumination (ΔR2=.06, p=.11). Furthermore, none of the three included variables (amygdala, hippocampus, and connecitivity) explained significant independent variance at step 3. .

Discussion

Self-reported rumination has been associated with impaired inhibition of negative information, particularly in the context of depression (Joormann, 2006; Joormann & Gotlib, 2008; Zetsche, D’Avanzato, & Joormann, 2012). Using a task with alternating emotional appraisal and executive control demands, we examined relationships between empirically-defined dimensions of trait rumination and sustained neural responses to alternating negative word appraisal and digit-sorting demands in a clinically depressed sample. All three trait rumination factors were significantly positively associated with increased sustained amygdala reactivity during the digit-sorting portion of the task. These relationships were frequently observed even when controlling for the severity of other depressive symptoms. Given the amygdala’s established functions of bottom-up attention capture and generation of negative mood states (LeDoux, 1996), these results potentially reflect sustained involuntary processing of salient negative information in depressed ruminators. Of note, the alternating task used in the present study was not designed to explicitly induce rumination; rather, it was designed to elicit several potential processes that might play a role in perseverative emotion-processing (e.g., attention to and elaboration on emotional information, difficulty switching from an emotional to a non-emotional task, resumption of elaboration on emotional information, etc.). Although the present design did not allow us to differentiate precisely which of the processes we taking place at any given time, the associations we observed indicate that habitual rumination may occur in concert with aberrant neural reactivity outside of discreet episodes of rumination. While we have previously found rumination to be associated with sustained amygdala reactivity to negative stimuli (e.g., Siegle, et al., 2002a), the present findings showed that this pattern occurred even after participants had presumably redirected their attention toward non-emotional digit-sorting. Such findings are in line with previous behavioral evidence that depressed individuals with higher self-reported rumination experience stronger residual activation of negative information in working memory (Joormann & Gotlib, 2008; Zetsche, et al., 2012).

Notably, our strongest amygdala findings related to the rumination factor supposedly reflecting “adaptive” cognitive responses to negative emotions and events (e.g., “Constructive rumination”), which should theoretically produce less emotional reactivity. It is also striking that this type of rumination was the only one associated with increased early amygdala reactivity during the appraisal of negative words, possibly indicating an increased engagement with affect-eliciting stimuli in individuals who view their repetitive thinking as constructive (Papageorgiou & Wells, 2001). This interpretation is supported by behavioral results indicating that these individuals were also better at correctly identifying the valence of negative words. Given the active nature of the strategies reportedly used by these ruminators, it possible that depressed individuals who ruminate in this way engage additional motivational resources to meet challenges and put forth effort toward problem-solving (e.g., CITE Pessoa, 2008). However, if this is the case, this additional energetic recruitment did not appear to be elicited in service of cognitive control, as high Constructive ruminators showed no evidence of increased dlPFC activity or of better performance on the subsequent cognitive task.

We also found that the rumination factor uniquely reflecting recurrent thoughts about negative events (i.e., “Event-related rumination”) was inversely associated with initial amygdala responses to negative words, with very high ruminators showing decreased reactivity. However, these individuals subsequently showed greater amygdala reactivity towards the end of the digit-sorting task, suggesting a possible “rebound” effect in occurring the absence of active task engagement. This interpretation would be consistent with previous reports of associations between rumination, cognitive avoidance, and subsequent distress in individuals who experience unwanted memories as threatening (Starr & Moulds, 2006; Williams & Moulds, 2008). However, Furthermore, for depressed individuals who tend not to dwell on recent negative events and emotions, the relatively greater amygdala reactivity observed during negative word identification may be a result of a greater need for emotional reactivity in order to directly focus attention on emotional material.

An additional aim of the present study was to explore whether task-related activation in additional regions previously associated with rumination was associated with our rumination factors and whether this activation was useful in explaining individual differences in rumination beyond the amygdala. We have previously found decreased dlPFC activation in depressed individuals relative to controls on the same digit-sorting task presented without alternating emotion-processing demands (Siegle, et al., 2007b). Although we failed to find associations with empirically-derived dimensions of rumination and a functionally-defined left dlPFC region, negative associations of activity from anatomical masks could potentially indicate decreased cognitive control during negative emotion processing in some types of ruminators. The large size of these regions does not allow us to differentiate dlPFC subregions that serve a cognitive versus and emotion-regulatory function, or both. Given the noted heterogeneity within this structure, more research is needed to confirm the nature of this negative association with rumination. Furthermore, as multiple regions displayed suggestive negative relationships with rumination (anterior insula, posterior cingulate, anatomical dlPFC), with a larger sample size it is expected that independent effects of regions other than the amygdala, which are negatively related to rumination would be observed. Potentially, different individuals ruminate due to increased and sustained reactivity to emotional information, and others, to decreased inhibitory or emotional control.

We found additional associations with rumination in the bilateral hippocampus, right anterior insula, medial prefrontal cortex/BA10 and the posterior cingulate; however, the only associations that were significant after controlling for the amygdala were found in the hippocampus. Increased right hippocampal activation and decreased left hippocampal activation during digit-sorting were associated with higher Event-related rumination scores, while increased left hippocampal activation during negative word appraisal was associated with higher Constructive rumination scores. The hippocampus has been posited to play a role in emotional appraisal by providing a context for the evaluation of emotional stimuli in light of salient autobiographical memories (Phelps, 2004). However, the hippocampus has also been implicated in other functions unrelated to emotional memory, and we did not control for these alternative functions in the experimental task we used. Thus, we can only speculate about the role of hippocampal activation in the present study, however it is noteworthy that the hippocampus was the only region out of the brain areas we investigated to emerge as an independent predictor of rumination when controlling for amygdala reactivity. Our results there suggest a potential value of focusing on hippocampal-rumination relationships in future research.

The present study has several limitations. First, although past research has linked both trait rumination and neural activation to the clinical course of depression, the cross-sectional nature of this study prevents us from characterizing observed neural patterns as causally related to future depressive episodes or to the maintenance of ruminative thinking over time. In addition, given previously-reported associations between rumination and age, longitudinal work would be useful in delineating the precise relationship between ruminative tendencies and brain function over the lifespan. Similarly, our speculations regarding the specific function of the amygdala in the present study could potentially be explained the differential recruitment of amygdala nuclei, which fMRI has a poor ability to specify. Our composite rumination scores were created by factor-analyzing multiple self-report scores on measures administered to the current sample. Given the small sample size, it will be important to replicate this factor structure in larger populations of depressed patients. Rumination measures having been administered on a different day from the fMRI tasks (to prevent fatigue), the previous administration of the alternating task outside the scanner during physiological assessment (to prevent novelty effects), and use of the same emotional words in another task (because it would have been prohibitive to obtain more emotional words) could all of weakened results. The large number of rumination questionnaires completed by each participant, while contributing valuable additional data, could also have led to fatigue, possibly impacting our results as well.

These limitations notwithstanding, results suggested reliable neural correlates of multiple types of trait rumination among clinically depressed individuals. They support a view of depressive rumination as a process in which automatic engagement of brain mechanisms associated with early emotional reactivity promotes the prolonged involuntary processing of negative material. This evidence of a broad association between individual differences in emotional reactivity and multiple ruminative response styles potentially emphasizes the importance of addressing these more basic biological processes when treating ruminative patients. Currently, treatments such as Cognitive Behavior Therapy (e.g., Beck, Rush, Shaw, & Emery, 1979) are purported to reduce bottom-up affective responses by recruiting greater cognitive control and encouraging more strategic processing of emotional material. However, given the present findings, rumination could potentially be addressed by pharmacological or neurobehavioral interventions more directly targeting amygdala reactivity. A potential next step from this work could involve examination of the extent to which different kinds of rumination are addressed by these types of treatment approaches.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the contributions of Roma Konecky, Lisa Farace, Agnes Haggerty, Mauri Cesare, Mandy Collier, Kelly Magee, Neil Jones, and the staff of the Mood Disorders Treatment and Research Program at Western Psychiatric Institute and Clinic.

This research was supported by MH082998, MH064159, MH60473, MH55762, MH58356, NARSAD, the Veteran’s Administration, and the Veteran’s Research Foundation. This material is the result of work supported with resources and the use of facilities at the Pittsburgh VA Healthcare System, Highland Drive Division.

Footnotes

The full battery of tasks, to be reported on in separate publications, included a personal relevance rating task, a Stroop task, a cued-reaction-time task, an emotional Stroop task (for a few participants), and the alternating digit-sorting/emotion-identification task described here. Each of these tasks used the same emotional words.

No neuroimaging data from this paper has been previously published. However, data from separate tasks in some of the same participants has been included in previous papers. Thirteen of the depressed participants in the present study contributed fMRI data from a personal relevance rating task in Siegle, et al.(2006). 17 contributed fMRI data for Siegle, et al. (2007b) on personal relevance rating and digit sorting tasks administered separately. 15 contributed pupillometry data for Siegle et al. (2011) on this task completed outside the scanner. Additional information on which specific depressed participants were used and the data they contributed to each study can be found in Supplement VI.

References

- Arnsten AF. Stress signalling pathways that impair prefrontal cortex structure and function. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2009;10(6):410–422. doi: 10.1038/nrn2648nrn2648. [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Rush AJ, Shaw BF, Emery G. Cognitive therapy of depression. New York: Guilford Press; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown G. Beck Depression Inventory Second Edition Manual. San Antonio: The Psychological Corporation; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Berman MG, Nee DE, Casement M, Kim HS, Deldin P, Kross E, Hamilton P. Neural and behavioral effects of interference resolution in depression and rumination. Cognitive, Affective, & Behavioral Neuroscience. 2011;11(1):85–96. doi: 10.3758/s13415-010-0014-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bishop SJ. Neurocognitive mechanisms of anxiety: An integrative account. [Peer Reviewed] Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2007;11(7) doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2007.05.00817553730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bishop SJ, Duncan J, Lawrence AD. State anxiety modulation of the amygdala response to unattended threat-related stimuli. The Journal of neuroscience. 2004;24(46):10364–10368. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2550-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley MM, Lang PJ. Affective Norms for English Words ANEW Technical Manual and Affective Ratings. Gainsville FL: The Center for Research in Psychophysiology University of Florida; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Buhle JT, Silvers JA, Wager TD, Lopez R, Onyemekwu C, Kober H, Ochsner KN. Cognitive Reappraisal of Emotion: A Meta-Analysis of Human Neuroimaging Studies. Cereb Cortex. 2013 doi: 10.1093/cercor/bht154. bht154 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooney RE, Joormann J, Eugene F, Dennis EL, Gotlib IH. Neural correlates of rumination in depression. Cognitive Affective & Behavioral Neuroscience. 2010;10(4):470–478. doi: 10.3758/CABN.10.4.470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson RJ. Affective style psychopathology and resilience: Brain mechanisms and plasticity. American Psychologist. 2000;55:1196–1214. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.55.11.1196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Lissnyder E, Derakshan N, De Raedt R, Koster EH. Depressive symptoms and cognitive control in a mixed antisaccade task: specific effects of depressive rumination. Cognition and Emotion. 2011;25(5):886–897. doi: 10.1080/02699931.2010.514711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denson TF, Pedersen WC, Ronquillo J, Nandy AS. The angry brain: Neural correlates of anger, angry rumination, and aggressive personality. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 2009;21(4):734–744. doi: 10.1162/jocn.2009.21051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drevets WC, Raichle M. Reciprocal suppression of regional cerebral blood flow during emotional versus higher cognitive processes: Implications for interactions between emotion and cognition. Cognition and Emotion. 1998;12:353–385. [Google Scholar]

- Fabiansson EC, Denson TF, Moulds ML, Grisham JR, Schira MM. Don’t look back in anger: neural correlates of reappraisal, analytical rumination, and angry rumination during recall of an anger-inducing autobiographical memory. NeuroImage. 2012;59(3):2974–2981. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.09.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fales CL, Barch DM, Rundle MM, Mintun MA, Snyder AZ, Cohen JD, Sheline YI. Altered emotional interference processing in affective and cognitive-control brain circuitry in major depression. Biological Psychiatry. 2008;63(4):377. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.06.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JB. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM IV Axis I Disorders Patient Edition. Vol. 20. New York: Biometrics Research Department New York State Psychiatric Institute; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Fortin NJ, Agster KL, Eichenbaum HB. Critical role of the hippocampus in memory for sequences of events. Nature Neuroscience. 2002;5(5):458–462. doi: 10.1038/nn834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fritz HL. Rumination and adjustment to a first coronary event. Psychosomatic Medicine. 1999;61(1):105. [Google Scholar]

- Goeleven E, De Raedt R, Baert S, Koster EH. Deficient inhibition of emotional information in depression. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2006;93:149–157. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2006.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gusnard DA, Akbudak E, Shulman GL, Raichle ME. Medial prefrontal cortex and self-referential mental activity: Relation to a default mode of brain function. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2001;98(7):4259–4264. doi: 10.1073/pnas.071043098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guthrie D, Buchwald JS. Significance testing of difference potentials. Psychophysiology. 1991;28(2):240–244. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.1991.tb00417.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton JP, Furman DJ, Chang C, Thomason ME, Dennis E, Gotlib IH. Default-Mode and Task-Positive Network Activity in Major Depressive Disorder: Implications for Adaptive and Maladaptive Rumination. Biological Psychiatry. 2011;70(4):327–333. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2011.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton JP, Glover GH, Hsu JJ, Johnson RF, Gotlib IH. Modulation of subgenual anterior cingulate cortex activity with real-time neurofeedback. Human Brain Mapping. 2011;32(1):22–31. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He G, Muller HG, Wang JL. Methods of Canonical Analysis for Functional Data. Journal of Statistical Planning and Inference. 2004;122:141–159. [Google Scholar]

- Horowitz MJ, Wilner N, Alvarez W. Impact of Event Scale: A measure of subjective stress. Psychosomatic Medicine. 1979;41 doi: 10.1097/00006842-197905000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingram RE. Toward an information-processing analysis of depression. Cognitive Therapy & Research. 1984;8(5):443–477. [Google Scholar]

- Insel T, Cuthbert B, Garvey M, Heinssen R, Pine DS, Quinn K, Wang P. Research domain criteria (RDoC): toward a new classification framework for research on mental disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2010;167(7):748–751. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.09091379. 167/7/748 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MK, Nolen-Hoeksema S, Mitchell KJ, Levin Y. Medial cortex activity, self-reflection and depression. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience. 2009;4(4):313–327. doi: 10.1093/scan/nsp022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MK, Raye CL, Mitchell KJ, Touryan SR, Greene EJ, Nolen-Hoeksema S. Dissociating medial frontal and posterior cingulate activity during self-reflection. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience. 2006;1(1):56–64. doi: 10.1093/scan/nsl004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnstone T, van Reekum CM, Urry HL, Kalin NH, Davidson RJ. Failure to regulate: counterproductive recruitment of top-down prefrontal-subcortical circuitry in major depression. J Neurosci. 2007;27(33):8877–8884. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2063-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joormann J. Differential Effects of Rumination and Dysphoria on the Inhibition of Irrelevant Emotional Material: Evidence from a Negative Priming Task. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2006;30(2):149–160. doi: 10.1007/s10608-006-9035-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Joormann J, Gotlib IH. Updating the contents of working memory in depression: interference from irrelevant negative material. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2008;117(1):182–192. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.117.1.182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joormann J, Levens SM, Gotlib IH. Sticky Thoughts Depression and Rumination Are Associated With Difficulties Manipulating Emotional Material in Working Memory. Psychological science. 2011;22(8):979–983. doi: 10.1177/0956797611415539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kensinger EA, Corkin S. Effect of negative emotional content on working memory and long-term memory. Emotion. 2003;3(4):378. doi: 10.1037/1528-3542.3.4.378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koster EHW, De Lissnyder E, Derakshan N, De Raedt R. Understanding depressive rumination from a cognitive science perspective: The impaired disengagement hypothesis. Clinical Psychology Review. 2011;31(1):138–145. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kühn S, Vanderhasselt MA, De Raedt R, Gallinat J. Why ruminators won’t stop: the structural and resting state correlates of rumination and its relation to depression. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2012;141(2–3):352–360. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2012.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawson C, MacLeod C, Hammond G. Interpretation revealed in the blink of an eye: depressive bias in the resolution of ambiguity. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2002;111(2):321. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.111.2.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeDoux JE. The Emotional Brain: The Mysterious Underpinnings of Emotional Life. Simon & Schuster; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Leppänen JM, Milders M, Bell JS, Terriere E, Hietanen JK. Depression biases the recognition of emotionally neutral faces. Psychiatry research. 2004;128(2):123–133. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2004.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathews A, MacLeod C. Cognitive vulnerability to emotional disorders. Annual review of clinical psychology. 2005;1:167–195. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.143916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayberg HS, Liotti M, Brannan SK, McGinnis BS, Mahurin RK, Jerabek PA, Fox PT. Reciprocal limbic cortical function and negative mood Converging PET findings in depression and normal sadness. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1999;156:675–682. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.5.675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayberg HS, Lozano AM, Voon V, McNeely HE, Seminowicz D, Hamani C, Kennedy SH. Deep brain stimulation for treatment-resistant depression. Neuron. 2005;45(5):651–660. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moberly NJ, Watkins ER. Ruminative self-focus, negative life events, and negative affect. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2008;46(9):1034. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2008.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson HE, Willison J. The National Adult Reading Test. Berkshire, England: Nfer-Nelson Publishing Co; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S. Responses to depression and their effects on the duration of depressive episodes. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1991;100(4):569–582. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.100.4.569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S, Morrow J, Fredrickson BL. Response styles and the duration of episodes of depressed mood. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1993;102(1):20–28. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.102.1.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ochsner KN, Bunge SA, Gross JJ, Gabrieli JDE. Rethinking feelings: An fMRI study of the cognitive regulation of emotion. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 2002;14(8):1215–1229. doi: 10.1162/089892902760807212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ochsner KN, Ray RD, Cooper JC, Robertson ER, Chopra S, Gabrieli JD, Gross JJ. For better or for worse: neural systems supporting the cognitive down- and up-regulation of negative emotion. Neuroimage. 2004;23(2):483–499. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.06.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papageorgiou C, Wells A. Process and meta cognitive dimensions of depressive and anxious thoughts and relationships with emotional intensity. Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy. 1999;6:152–162. [Google Scholar]

- Papageorgiou C, Wells A. Metacognitive beliefs about rumination in recurrent major depression. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. 2001;8(2):160–164. [Google Scholar]

- Paulus MP, Stein MB. An insular view of anxiety. Biological psychiatry. 2006;60(4):383–387. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.03.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phelps EA. Human emotion and memory: interactions of the amygdala and hippocampal complex. Current opinion in neurobiology. 2004;14(2):198–202. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2004.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips M, Ladouceur C, Drevets W. A neural model of voluntary and automatic emotion regulation: implications for understanding the pathophysiology and neurodevelopment of bipolar disorder. Molecular psychiatry. 2008a;13(9):833–857. doi: 10.1038/mp.2008.65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips ML, Ladouceur CD, Drevets WC. A neural model of voluntary and automatic emotion regulation: implications for understanding the pathophysiology and neurodevelopment of bipolar disorder. Molecular psychiatry. 2008b;13(9):833–857. doi: 10.1038/mp.2008.65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porrino LJ, Crane AM, Goldman-Rakic PS. Direct and indirect pathways from the amygdala to the frontal lobe in rhesus monkeys. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1981;198(1):121–136. doi: 10.1002/cne.901980111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramsay JO, Silverman BW. Functional Data Analysis. New York: Springer; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Ratcliff R. Methods for dealing with reaction time outliers. Psychological Bulletin. 1993;114:510–532. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.114.3.510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ray RD, Ochsner KN, Cooper JC, Robertson ER, Gabrieli JD, Gross JJ. Individual differences in trait rumination and the neural systems supporting cognitive reappraisal. Cognitive Affective & Behavioral Neuroscience. 2005;5(2):156–168. doi: 10.3758/cabn.5.2.156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson PN. Deep phenotyping for precision medicine. Hum Mutat. 2012;33(5):777–780. doi: 10.1002/humu.22080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roger D, Najarian B. The construction and validation of a new scale for measuring emotion control. Personality and individual differences. 1989;10(8):845–853. [Google Scholar]

- Scott VB, McIntosh WD. The development of a trait measure of ruminative thought. Personality and individual differences. 1999;26(6):1045–1056. [Google Scholar]

- Siegle GJ. The Balanced Affective Word List Creation Program. 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Siegle GJ, Carter CS, Thase ME. Use of fMRI to predict recovery from unipolar depression with cognitive behavior therapy. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2006;163(4):735–738. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.4.735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegle GJ, Moore P, Thase ME. Rumination: One construct, many features in healthy individuals, depressed individuals, and individuals with Lupus. Cognitive Therapy & Research. 2004;28:645–668. [Google Scholar]

- Siegle GJ, Steinhauer SR, Carter CS, Ramel W, Thase ME. Do the seconds turn into hours? Relationships between sustained pupil dilation in response to emotional information and self-reported rumination. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2003a;27(3):365–382. [Google Scholar]

- Siegle GJ, Steinhauer SR, Friedman ES, Thompson WS, Thase ME. Remission Prognosis for Cognitive Therapy for Recurrent Depression Using the Pupil: Utility and Neural Correlates. Biological Psychiatry. 2011;69(8):726–733. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.12.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegle GJ, Steinhauer SR, Stenger VA, Konecky R, Carter CS. Use of concurrent pupil dilation assessment to inform interpretation and analysis of fMRI data. NeuroImage. 2003b;20(1):114–124. doi: 10.1016/s1053-8119(03)00298-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegle GJ, Steinhauer SR, Thase ME, Stenger VA, Carter CS. Can’t shake that feeling: Event-related fMRI assessment of sustained amygdala activity in response to emotional information in depressed individuals. [Journal Peer Reviewed Journal] Biological Psychiatry. 2002a;51(9):693–707. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(02)01314-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegle GJ, Steinhauer SR, Thase ME, Stenger VA, Carter CS. Can’t shake that feeling: fMRI assessment of sustained amygdala activity in response to emotional information in depressed individuals. Biological Psychiatry. 2002b;51:693–707. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(02)01314-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegle GJ, Thompson W, Carter CS, Steinhauer SR, Thase ME. Increased amygdala and decreased dorsolateral prefrontal BOLD responses in unipolar depression: Related and independent features. Biol Psychiatry. 2007a;61(2):198–209. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.05.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegle GJ, Thompson WK, Carter CS, Steinhauer SR, Thase ME. Increased amygdala and decreased dorsolateral prefrontal BOLD responses in unipolar depression: related and independent features. Biological Psychiatry. 2007b;61(2):198–209. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.05.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegle GJ, Thompson WK, Collier A, Berman SR, Feldmiller J, Thase ME, Friedman ES. Toward Clinically Useful Neuroimaging in Depression Treatment: Prognostic Utility of Subgenual Cingulate Activity for Determining Depression Outcome in Cognitive Therapy Across Studies, Scanners, and Patient Characteristics. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2012;69(9):913–924. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2012.65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spasojevic J, Alloy LB. Rumination as a common mechanism relating depressive risk factors to depression. Emotion. 2001;1(1):25–37. doi: 10.1037/1528-3542.1.1.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starr S, Moulds ML. The role of negative interpretations of intrusive memories in depression. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2006;93(1):125–132. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2006.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas EJ, Elliott R, McKie S, Arnone D, Downey D, Juhasz G, Anderson IM. Interaction between a history of depression and rumination on neural response to emotional faces. Psychological Medicine. 2011;41(9):1845–1855. doi: 10.1017/S0033291711000043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson WK, Siegle G. A stimulus–locked vector autoregressive model for slow event-related fMRI designs. Neuroimage. 2009a;46(3):739–748. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.02.011. S1053-8119(09)00154-2 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson WK, Siegle GJ. A stimulus-locked vector autoregressive model for slow event-related fMRI designs. NeuroImage. 2009b;46(3):739–748. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanderhasselt MA, Kuhn S, De Raedt R. Healthy brooders employ more attentional resources when disengaging from the negative: an event-related fMRI study. Cogn Affect Behav Neurosci. 2011;11(2):207–216. doi: 10.3758/s13415-011-0022-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]