Abstract

Background

We have previously demonstrated that tolerance to a vascularized composite allograft (VCA) can be achieved after the establishment of mixed chimerism. Here, we test the hypothesis that tolerance to a VCA in our dog leukocyte antigen (DLA)-matched canine model is not dependent on the previous establishment of mixed chimerism and can be induced coincident with hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT).

Methods

Eight DLA-matched, minor antigen mismatched dogs received 200 cGy of radiation and a VCA transplant. Four dogs received donor bone marrow at the time of VCA transplantation (group 1) while a second group of 4 dogs did not (group 2). All recipients received a limited course of post-grafting immunosuppression. All dogs that received HCT and VCA were given donor, third party and autologous skin grafts.

Results

All group 1 recipients were tolerant to their VCA (> 62 weeks). Three of the four dogs in group 2 rejected their VCA transplants after the cessation of immunosuppression. Biopsies obtained from muscle and skin of VCA from group 1 showed few infiltrating cells compared to extensive infiltrates in biopsies of VCA from group 2. Compared to autologous skin and muscle, elevated levels of CD3+ FoxP3+ T-regulatory cells were found in skin and muscle obtained from VCA of HCT recipients. All group 1 animals were tolerant to their donor skin graft and promptly rejected the third-part skin grafts.

Conclusion

These data demonstrated donor specific tolerance to all components of the VCA can be established through simultaneous nonmyeloablative allogeneic HCT and VCA transplant protocol.

Keywords: dog, nonmyeloablative conditioning regimen, hematopoietic cell transplantation, vascularized composite allograft, skin allograft, FoxP3, tolerance

INTRODUCTION

The development of safe and reliable protocols for the transplantation of the face and hands without long-term immunosuppression is needed (1–4). Transplantation of vascularized composite allografts (VCA) within the background of the toleragenic properties of hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT) in a large animal model makes progress towards this end. A clinically relevant tolerance induction protocol for the transplantation of VCA must fulfill certain specific criteria. First, the conditioning regimen of the recipient must avoid significant morbidity. Second, the regimen must be suitable for the scenario of adult cadaveric transplantation and, as such, not require a prolonged period of recipient conditioning. Finally, the regimen should ideally induce tolerance to all elements of a VCA, including the skin. We have previously demonstrated that long-term tolerance to a VCA can be achieved after the establishment of stable mixed chimerism in a DLA-identical dog model (5). Unlike previous reports in other large animal models where split tolerance was observed, these animals accepted the skin and muscle for periods greater than 1 year (6–7). However, our previous protocol required that the bone marrow transplant be performed months before the VCA transplant. Clearly, a delay between HCT-mediated induction of tolerance and VCA transplantation poses a significant limitation for cadaveric transplantation. Thus, we sought to consolidate the elements of our previous protocol into a single day procedure in our established DLA-identical model.

Here, we test the hypothesis that simultaneous transplantation of HCT and a VCA using our well-established nonmyeloablative conditioning regimen leads to tolerance of the VCA. The induction of tolerance to the VCA appears to be dependent on the initiation of mixed hematopoietic chimerism but not on the long-term engraftment of the HCT. Furthermore, tolerance to the allograft appears to be influenced by the presence of infiltrating cells of the T-regulatory phenotype.

RESULTS

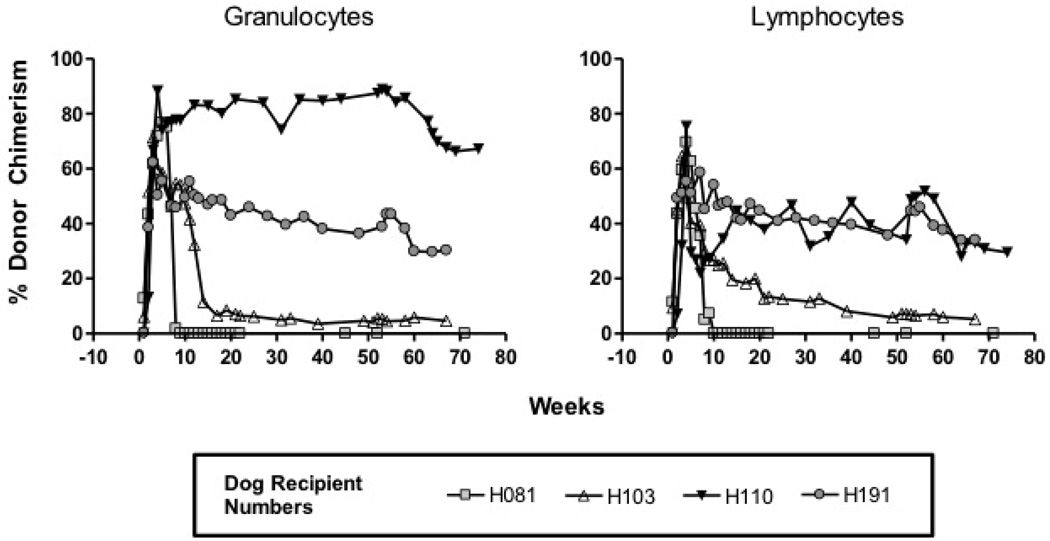

Mixed Donor/Host Hematopoietic Chimerism

Table 1 summarizes the bone marrow dose, level of donor chimerism in recipient dogs, and transplant outcome. In group 1, donor lymphocyte chimerism, at time of necropsy, ranged from 0–34% and granulocyte chimerism ranged from 0–67% (Figure 1). Of note, one of four dogs transplanted (H081) lost detectable donor granulocytes and lymphocytes by week 9 and 10, respectively, but remained tolerant to the VCA transplant (Figure 1, Table 1). By definition, no dog in group 2 demonstrated evidence of donor cell chimerism.

Table 1.

Vascularized Composite Tissue Transplantation with and without Hematopoietic Stem Cell Infusion.

| Group | Recipient | Donor Marrow Cells × 108 / kg |

% Donor Chimerism at Necropsy |

Weeks of Allograft Survival Post IS |

Graft Rejection |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Granulocytes | Lymphocytes | |||||

| Group 1 | H081 | 1.7 | 0 | 0 | 66 | No |

| H103 | 4.7 | 4.6 | 5.2 | 62 | No | |

| H110 | 5.1 | 67.2 | 29.6 | 69 | No | |

| H191 | 2.8 | 30.2 | 34.1 | 62 | No | |

| Group 2 | H334 | N/A | 0 | 0 | <5 | Yes |

| H369 | N/A | 0 | 0 | <3 | Yes | |

| H425 | N/A | 0 | 0 | <3 | Yes | |

| H483 | N/A | 0 | 0 | >18 | No | |

Figure 1. Donor cell chimerism observed after simultaneous transplantation of HSC and VCA.

The graphs depict the course of donor cell chimerism (lymphocytes and granulocytes) in those animals that received a bone marrow infusion (H081, H103, H110, and H191) and a simultaneous VCA transplant.

Transplantation of Vascularized Composite Allografts

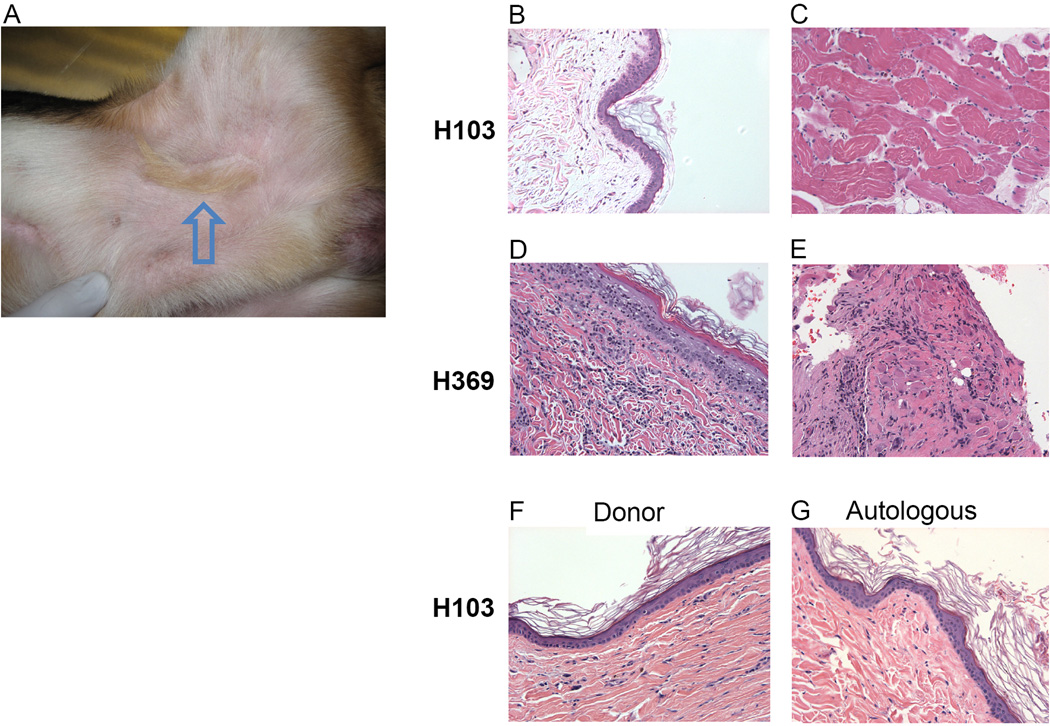

Four dogs in group 1 received simultaneous hematopoietic stem cell and vascularized composite transplants from their respective DLA-identical littermates. These four dogs accepted the VCA from their marrow donors with observation periods ranging from 62–69 (mean 65) weeks, at which point the allografts were considered permanent (Table 1). Acceptance was indicated clinically by normal skin color and hair growth of the VCA (Figure 2A). Histologically, serial biopsies of skin (Figure 2B) and muscle (Figure 2C) from the VCA after transplantation showed minimal evidence of cellular infiltrate (Banff Grade 0 and Grade 0R, respectively) and no evidence of vascular disease or epidermal architecture damage.

Figure 2. Skin and muscle from group 1 and group 2.

(A) Photograph of long-term acceptance of VCA (arrow) in groin of an animal from group 1 (H081) 66 weeks after transplant. Histology of composite skin (B) and muscle (C) from recipient in group 1, H103, showing lack of cellular infiltrate. Histology of composite skin (D) and muscle (E) biopsies collected from group 2 recipient showing acute rejection. Histology of biopsies from non-vascularized donor (F) and autologous (G) skin grafts from group 1 recipient showing absence of infiltrating lymphocytes. Slides were photographed at 200× magnification.

In Group 2, four dogs underwent a VCA transplant after undergoing the identical conditioning regimen as described for Group 1 but without the infusion of hematopoietic stem cells (HSC) (Table 1). All dogs underwent successful transplantation and the allograft demonstrated normal healing and hair growth. However, as early as 3 weeks following completion of post-grafting immunosuppression, the allografts showed clinical signs of rejection (increased erythema and edema). Three of the four allografts were rejected by 5 weeks after immunosuppression was stopped. Rejection was confirmed histologically by biopsies of skin and muscle obtained during the rejection process that revealed lymphocytic infiltrate (Banff Grade IV and Grade 3R, respectively) in both skin (Figure 2D) and muscle (Figure 2E). One of the dogs (H483) demonstrated initial evidence for acute rejection (Grade II) but went on to accept the transplant long-term (>18 weeks).

Full Thickness Skin Grafts

All four of the dogs in group 1 demonstrated long-term tolerance to their VCA and went on to accept their donor VCA skin grafts (>100 days) (Figure 2F). Each of the recipients promptly rejected the unrelated (i.e., major histocompatibility disparate) skin grafts (range, 7–14 days) while maintaining indefinite survival of autologous grafts (2G). No dog in group 2 underwent a donor skin graft.

Cytokine Expression and CD3+ T-Regulatory Cells from Peripheral Blood and VCA

CD3+ T-cells were isolated from the blood from groups 1 and 2 and analyzed for the expression of FoxP3, Grβ, IL-10 and TGFβ. The expression of FoxP3 in CD3+ cells from the peripheral blood was significantly elevated during the first 10 weeks after transplantation in group 1 whereas CD3+ cells in group 2 had much lower expression of FoxP3 (Supplemental Digital Content (SDC), Figure 1. An inverse relationship was noted in the expression of Grβ where dogs in group 2 showed higher levels of Grβ when compared to dogs in group 1

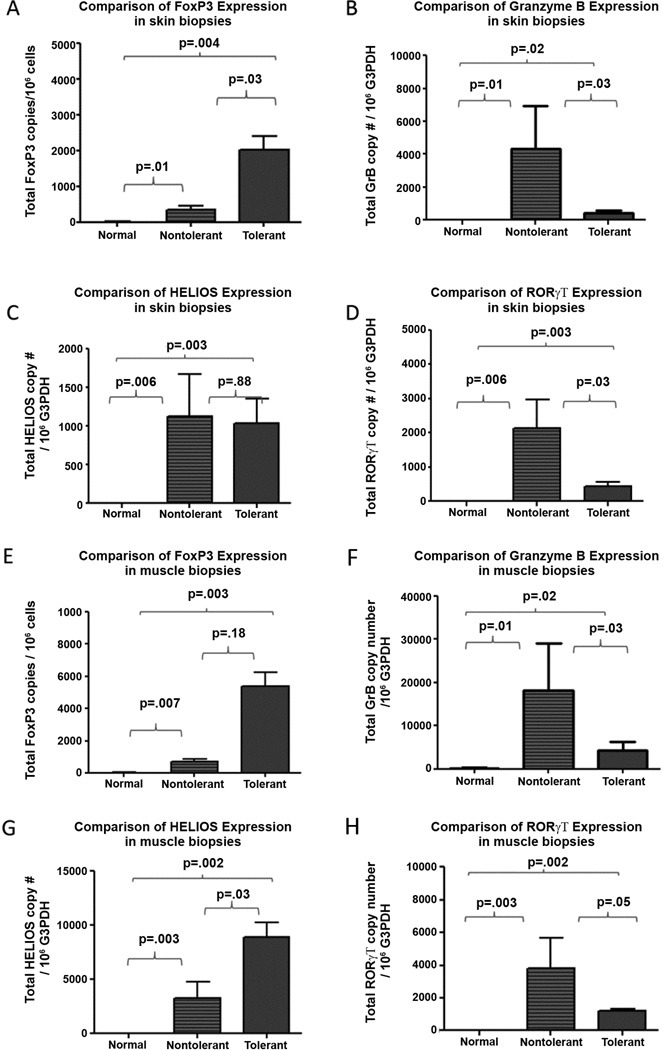

Cytokine Expression and CD3+ T-Regulatory Cells from the VCA in Tolerant and Non-tolerant Animals

CD3+ T-cells were isolated from muscle and skin of the VCA, from dogs in both the tolerant and non-tolerant animals. Dogs in the tolerant group showed higher expression of FoxP3 in the skin and muscle when compared to expression in the non-tolerant animals (figure 3A, E). Helios expression was significantly elevated in the muscle but not in the skin in the tolerant animals when compared to the non-tolerant animals (figure 3C, G). Finally, expression of IL-10 was significantly elevated in tolerant animals when compared to the non-tolerant animals (SDC Figure 2B, F). TGFβ expression was similar in both groups (SDC Figure 2 A, E).

Figure 3. FoxP3, Helios, Granzyme B, and ROR-Gamma expression in biopsies of skin(A – D)_ and muscle (E – H) from allografts in both tolerant and non-tolerant and normal tissues.

Biopsies of skin and muscle were collected from VCA of both tolerant and non-tolerant animals and were analyzed for expression via RT-PCR techniques.

Muscle and skin biopsies obtained from the non-tolerant animals demonstrated infiltrating T-cells (indicating on-going rejection) with a statistically significant increase in the expression of Grβ when compared to the tolerant animals Figure 3B, F). Significantly elevated expression was also noted for ROR-gamma (Figure 3D and H) and the pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-6 and IL-8 when compared to the tolerant animals (SDC Figure 2D, H, C, G).

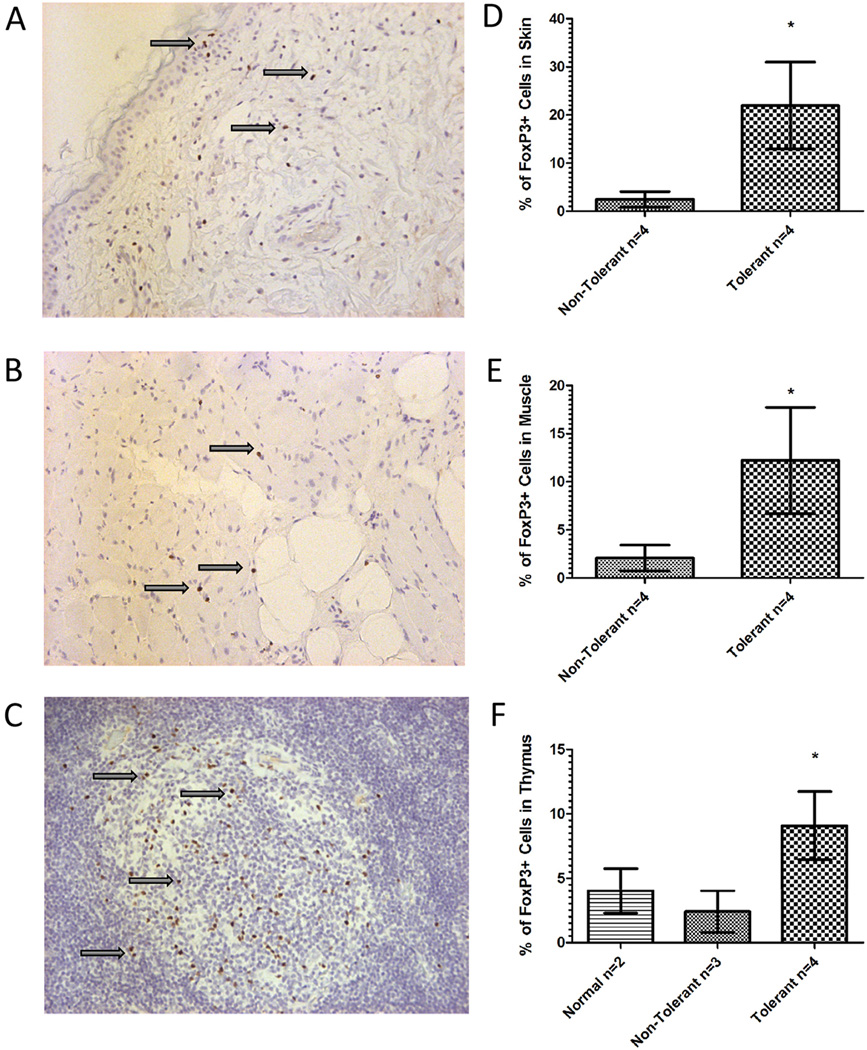

In Situ Detection of T-regulatory Cells within Muscle and Skin Biopsies of Vascularized Composite Allografts from Long-Term Mixed Chimeric Recipients

Muscle and skin biopsies from VCA in group 1 revealed consistently high levels of expression of FoxP3 over the course of the transplant (> 1 year), as demonstrated both by RT-PCR and immunohistochemistry analyses (Figure 4). Cells staining positive for FoxP3 were localized to limited areas of higher cellularity in both muscle and skin biopsies from group 1 dogs. These results further confirm the observations that T-regulatory cells are present within tissues of VCA derived from group 1.

Figure 4. FoxP3+ staining of muscle and skin biopsies from untreated dogs, bone marrow donor dogs and vascularized composite allografts.

Representative muscle (A) skin (B) and thymus (C) biopsies from the vascularized composite allograft of a tolerant group 1 dog reveals increased FoxP3+ staining with limited cellular infiltrate (Arrowheads; 400× magnification). T-regulatory cells in the transplanted allograft were quantified for the overall percentage of FoxP3 staining in the skin (D), muscle (E) and thymus (F). (Statistically significant, * designates P ≤ 0.05, two tailed Student’s T-test).

Because lymphocytic infiltrates could be observed within some of the biopsies of transplanted skin and muscle in group 1 recipients, we sought to determine whether the percentages of FoxP3+ cells present within those sections were greater than tissues from VCA derived from group 2. As shown (Figure 4), the average percent of FoxP3+ cells present in the lymphocytic infiltrate of the skin of the VCA in group 2 was 2.783±1.721, while that of group 1 recipients was significantly greater at 21.957± 9.0285. Similarly, the average percent of FoxP3+ cells in the infiltrate of the muscle of the VCA in group 2 was 2.133± 1.365, while that of group 1 recipient was significantly greater at 12.204 ± 5.532. Finally, a similar pattern was noted in the thymic tissue acquired at the end of the experiment. The average percentage of FoxP3+ cells was 9.095 ± 2.642 in the thymus of the tolerant dogs from group 1 while those dogs in group 2 had significantly lower average percentage of 2.017 ± 1.861. Thymic tissue removed from normal dogs also demonstrated a low average percentage of FoxP3+ cells 4.016 ± 7.34.

DISCUSSION

We have previously demonstrated that the establishment of hematopoietic chimerism following HCT can provide a stable platform for induction of tolerance to subsequent solid organ and VCA (5,8–11). However, to be clinically relevant to the field of reconstructive transplantation, the regimen must avoid the need for significant recipient pre-conditioning. In this study, we sought to determine whether tolerance to a VCA could be achieved in our DLA-matched canine model after the simultaneous transplantation of tissue and hematopoietic stem cells.

In this study, all four dogs that underwent simultaneous transplantation of VCA and hematopoietic stem cells (group 1) demonstrated long-term tolerance. These dogs possessed normal immune functions as evidenced by their acceptance of second donor skin graft and rejection of a third-party graft. These results confirmed that tolerance of a VCA is not dependent on the previous establishment of stable mixed chimerism.

In fact, tolerance towards VCA may not be dependent on long-term engraftment of the donor bone marrow. One of the dogs from group 1 (H081) lost detectable donor cell chimerism in the blood and marrow after week 12 but remained tolerant to the VCA allograft. There are both experimental and clinical reports of the maintenance of tolerance to renal allografts after only transient engraftment of the donor marrow transplant (12). This finding is further supported by our recent study where we demonstrated that donor hematopoietic chimerism could be eliminated intentionally after the establishment of mixed chimerism using 2 Gy TBI and an infusion of granulocyte colony stimulating factor-mobilized host PBMC collected pre-transplant. When this procedure was applied to mixed chimeric DLA-identical kidney transplant recipients, donor hematopoiesis was eliminated but not the kidney graft (13). The natural elimination of donor cell chimerism without rejection of a transplanted kidney was also observed clinically in five patients with end stage renal failure that received a combined nonmyeloablative marrow and kidney transplant from HLA single haplotype mismatched donors (14). Tolerance to a VCA with a skin component after only transient chimerism has been seen in small animal models, it has not been previously published in a large animal model (6,15–17).

The findings of tolerance to a VCA without long-term engraftment of the marrow component lead to the examination of the need for the hematopoietic stem cell transplant as part of the tolerance protocol. Previous studies in the swine model demonstrated that tolerance could be routinely established to a VCA but not the skin across a minor barrier with a 12-day course of high-dose cyclosporine (15,18). However, when a vascularized skin component was added in a subsequent experiment, only one of six swine demonstrated tolerance to the skin (6). Tolerance in this single animal was thought to be due to chance matching of the skin specific antigens. In our model, when transplants were performed with the conditioning regimen and post-grafting immunosuppression but without the administration of stem cells, three of the four animals rejected their transplant after the cessation of immunosuppression. One of the dogs in this group did not go on to reject the transplant despite an initial episode of biopsy-proven acute rejection. The long-term acceptance of this allograft can be attributed to the combination of the conditioning regimen combined with chance a matching of skin specific antigens.

A second component of our study was to further investigate the putative role of the regulatory environment in the maintenance of tolerance after simultaneous HCT and VCA transplantation. Our previous studies in the canine model demonstrated that the populations of regulatory T-cells were increased in the blood and peripheral tissue of tolerant animals after a lung or a VCA transplant into mixed chimeric recipients (5,9). In the present study, we again observed that the CD3+ cells derived from biopsies of the muscle and skin from VCA transplant maintained long-term expression of FoxP3. While it was not possible to identify the source of the T regs (donor or recipient) we did note that the T-regs present in the dog without long-term donor cell chimerism are most likely recipient in origin.

To further phenotype these cells we examined the cells for expression of Helios (an Ikaros family transcription factor that is preferentially expressed in regulatory T-cells) (19). The early studies suggested that Helios expression might distinguish thymic-derived from induced T-regulatory cells (20). However, this concept was recently challenged by the demonstration of Helios expression induced in a transgenic CD4 T-cells upon recognition of antigen in the presence of IL-2 and TGFβ. More recently, Zabransky, et al., demonstrated that Helios appears to be a marker of a Treg with functional suppressive capacity (21). In our experiments we noted elevated expression of Helios in the transplanted muscle and skin. This was not seen in muscle and skin taken from normal animals. The expression of Helios appeared to correlate with elevations in the expression of Foxp3.

In contrast, the cells harvested from the non-tolerant transplants were of a pro-inflammatory pathway with increased expression of Granzyme B and pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-6 and IL-8) and ROR-gamma (a marker for pro-inflammatory T helper 17 (Th17) that may be associated with rejection (22)). The dogs that went on to reject their transplants exhibited higher expression of ROR-gamma in cells derived from both the muscle and the skin. The expression of IL-6 and IL-8 was also noted to be elevated in the tissues that went on to reject when compared to the tolerant animals.

In this study we have demonstrated donor specific tolerance to all components of the VCA in a genetically out-bred DLA-matched canine model conferred through simultaneous nonmyeloablative allogeneic HCT and VCA transplantation. Tolerance induction appears to depend on the administration and initial engraftment of the donor HSC but not on persistent donor cell chimerism. Finally, the long-term presence of T-regulatory cells in the transplanted tissue correlated to a tolerant state.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Experimental Animals

Random-bred litters of beagles and mini-mongrel cross-breeds were either raised at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center (FHCRC), Seattle, WA, or purchased commercially. The dogs weighed from 9.0 to 15.2 (median 12.1) kg and were 7.5 to 15 (median 10.9) months old. The Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the FHCRC approved the research protocols, and the American Association for Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care certified the kennels. Eight littermate donor/recipient pairs were DLA-identical on the basis of matching for highly polymorphic major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I and class II micro-satellite markers (23). In addition, specific DLA-DRB1 allelic identity was confirmed by direct sequencing (24).

Nonmyeloablative Conditioning and HCT

All eight dogs received a single dose of 2 Gy TBI delivered at a rate of 7 cGy/min from a high-energy linear accelerator (Varian Clinac 6, Palo Alto, CA). The dogs were divided into two groups. Group 1 underwent transplantation of marrow from a respective DLA-identical littermate. Group 2 received TBI but no cells were infused. Marrow was infused i.v. within 4 hr of TBI at doses of 1.7 to 5.1 (median 3.6) × 108 nucleated cells/kg. Post-grafting immunosuppression consisted of mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) (10 mg/kg b.i.d., s.c., from day 0 to day 28) and cyclosporine (CSP) (15 mg/kg b.i.d. orally from day -1 to 35). All dogs were given standard postgrafting care (25). The dogs’ clinical status was assessed twice daily. White blood cell counts with differentials, platelet counts, and hematocrits were performed daily through day 21 and twice weekly thereafter.

Assessment of Hematopoietic Cell Engraftment

Percent donor chimerism was determined as previously described (26–28). Briefly, a polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-based assay was performed using specific primers for informative microsatellite markers. Primers amplified specific regions throughout the genome possessing tandem repeats in which the transplant recipient and donor were non-identical. PCR products were separated by capillary electrophoresis on an ABI Prism 310 Genetic Analyzer.

Vascularized Composite Allograft Transplantation

After receiving TBI and HCT, animals were anesthetized and underwent transplantation of a VCA. The surgical procedures for VCA transplantation have been previously described in detail (29). The allograft consists of a myocutaneous rectus abdominus flap and was transplanted to the groin of the recipient dog and anastomosed to the femoral vessels. The skin and muscle were followed via clinical examination for color of the skin and hair growth. Survival of the graft was determined by biopsy of the skin and muscle. Sections of tissue were fixed in 10% formalin, imbedded in paraffin, and cut sections were stained with hematoxylin-and-eosin and Jones’ stains. A pathologist (G.S.), blinded to the source of the biopsies, evaluated for rejection.

Nonvascularized Skin Grafts

After one year of stable VCA engraftment, full thickness skin grafts were placed on recipients to determine immunocompetency and donor specific tolerance. Each recipient received three skin grafts: autologous, VCA donor, and third party. Skin grafts were performed and monitored as previously published (5,8). End of study was either rejection of a skin graft or long-term tolerance over 100 days.

Functional Assays

Quantitative real time RT-PCR of intracellular cytokines, FoxP3, Helios, TGFβ, IL-6 IL-8, IL-10, RoRyt, and Granzyme B were performed on skin and muscle biopsies and on peripheral blood cells. Methods for selection, quantitative RT-PCR, and analysis in blood and biopsies were previously described (5,9). The sequences for primers used for detection of canine HELIOS and canine RORyt were: forward, 5’-TCACAACTATCTCCAGAATGTCAGC-3’, reverse primer, 5’-AGGCGGTACATGGTGACTCAT-3’ and probe, 6FAM 5’-TGGAGGCTGCCGGGCAGG-3’ TAMARA; forward, 5’-GAGGCCATTCAGTACGTGGT-3’, reverse, 5’-ACCAGAACCACTTCCATTGC-3’, probe, 6FAM 5’-GCTTTATGGAGCTCTGCCAG-3’ TAMARA. The sequences of the primers used for detection of canine IL-10, canine transforming growth factor (TGFβ), canine IL-6, canine IL-8, canine granyzme B (Grβ), and housekeeping gene, canine glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (G3PDH) have been previously published (1–4). Total copy numbers for gene expression was assessed by absolute quantitative RT-PCR and normalized to G3PDH.

FoxP3 Immunohistochemistry

FoxP3 immunohistochemistry was performed on deparaffinized tissues prepared using previously described standard methods (5). The tissues were stained with the anti-FoxP3 antibody (14–5773-82, eBioscience) and concentration matched isotype control slides were run for each tissue sample. Analysis for percentage of cells stained for FoxP3 was performed as previously published using Image J software (NIH, Bethesda, MD) (5). Statistical analysis was performed using a 2-tailed, type 3, student t-test, and statistical significance was defined as a P value less than or equal to 0.05.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding support information: The authors are grateful for research funding from the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, grants P01CA078902 and P30CA015704. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health nor its subsidiary Institutes and Centers. In addition, David Mathes received support from the National Endowment for Plastic Surgery Grant from the Plastic Surgery Foundation.

ABBREVIATIONS

Abbreviations must be listed at the beginning and defined in the text where first used EXCEPT for those in the lists provided.

- CSP

cyclosporine

- DLA

dog leukocyte antigen

- FHCRC

Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center

- FoxP3

Forkhead Box P3

- G3PDH

glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase

- Grβ

granzyme B

- GVHD

graft versus host disease

- HCT

hematopoietic cell transplantation

- IL-10

interleukin-10

- MLR

mixed leukocyte reactions

- MMF

mycophenolate mofetil

- PBMC

peripheral blood mononuclear cells

- PCR

polymerase chain reaction

- RT-PCR

reverse transcribed PCR

- TBI

total body irradiation

- TGFβ

transforming growth factor beta

- T-reg cells

T-regulatory cells

Footnotes

Authors' contributions:

D.W. Mathes: designed the study, performed the surgeries and co-wrote the manuscript.

B. Hwang: designed and performed the Treg cell studies and co-wrote the manuscript.

S.S. Graves: assisted in the design of the studies and co-wrote the manuscript.

J. Chang: assisted in the surgeries and co-wrote the manuscript.

B.E. Storer: performed the statistical analyses.

T. Miwongtum: performed chimerism analyses.

G. Sale: evaluated the histopathological samples.

R. Storb: designed and supervised the study and revised the manuscript.

Disclosures: This manuscript was neither prepared nor funded in any part by a commercial organization, including educational grants. The authors of this manuscript have no conflicts of interest to disclose as described by the journal Transplantation.

REFERENCES

- 1.Schneeberger S, Gorantla VS, van Riet RP, et al. Atypical acute rejection after hand transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2008;8:688–696. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2007.02105.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schneeberger S, Gorantla VS, Hautz T, Pulikkottil B, Margreiter R, Lee WP. Immunosuppression and rejection in human hand transplantation (Review) Transplant Proc. 2009;41:472–475. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2009.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lantieri L, Hivelin M, Audard V, et al. Feasibility, reproducibility, risks and benefits of face transplantation: a prospective study of outcomes. Am J Transplant. 2011;11:367–378. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2010.03406.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chang J, Davis CL, Mathes DW. The impact of current immunosuppression strategies in renal transplantation on the field of reconstructive transplantation (Review) Journal of Reconstructive Microsurgery. 2012;28:7–19. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1285988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mathes DW, Hwang B, Graves SS, et al. Tolerance to vascularized composite allografts in canine mixed hematopoietic chimeras. Transplantation. 2011;92:1301–1308. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e318237d6d4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mathes DW, Randolph MA, Solari MG, et al. Split tolerance to a composite tissue allograft in a swine model. Transplantation. 2003;75:25–31. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200301150-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hettiaratchy S, Melendy E, Randolph MA, et al. Tolerance to composite tissue allografts across a major histocompatibility barrier in miniature swine. Transplantation. 2004;77:514–521. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000113806.52063.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kuhr CS, Yunusov M, Sale G, Loretz C, Storb R. Long-term tolerance to kidney allografts in a preclinical canine model. Transplantation. 2007;84:545–547. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000270325.84036.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nash RA, Yunusov M, Abrams K, et al. Immunomodulatory effects of mixed hematopoietic chimerism: immune tolerance in canine model of lung transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2009;9:1037–1047. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2009.02619.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kuhr CS, Allen MD, Junghanss C, et al. Tolerance to vascularized kidney grafts in canine mixed hematopoietic chimeras. Transplantation. 2002;73:1487–1493. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200205150-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yunusov MY, Kuhr C, Georges GE, et al. Survival of small bowel transplants in canine mixed hematopoietic chimeras: preliminary results. Transplant Proc. 2002;34:3366–3367. doi: 10.1016/s0041-1345(02)03614-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kawai T, Cosimi AB, Colvin RB, et al. Mixed allogeneic chimerism and renal allograft tolerance in Cynomolgus monkeys. Transplantation. 1995;59:256–262. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Graves SS, Mathes DW, Georges GE, et al. Long-term tolerance to kidney allografts after induced rejection of donor hematopoietic chimerism in a preclinical canine model. Transplantation. 2012;94:562–568. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e3182646bf1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kawai T, Cosimi AB, Spitzer TR, et al. HLA-mismatched renal transplantation without maintenance immunosuppression. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:353–361. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa071074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bourget JL, Mathes DW, Nielsen GP, et al. Tolerance to musculoskeletal allografts with transient lymphocyte chimerism in miniature swine. Transplantation. 2001;71:851–856. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200104150-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xu H, Ramsey DM, Wu S, Bozulic LD, Ildstad ST. Simultaneous bone marrow and composite tissue transplantation in rats treated with nonmyeloablative conditioning promotes tolerance. Transplantation. 2013;95:301–308. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e31827899fc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rahhal DN, Xu H, Huang WC, et al. Dissociation between peripheral blood chimerism and tolerance to hindlimb composite tissue transplants: preferential localization of chimerism in donor bone. Transplantation. 2009;88:773–781. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e3181b47cfa. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee WP, Rubin JP, Bourget JL, et al. Tolerance to limb tissue allografts between swine matched for major histocompatibility complex antigens. Plastic & Reconstructive Surgery. 2001;107:1482–1490. doi: 10.1097/00006534-200105000-00027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Getnet D, Grosso JF, Goldberg MV, et al. A role for the transcription factor Helios in human CD4(+)CD25(+) regulatory T cells. Mol Immunol. 2010;47:1595–1600. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2010.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thornton AM, Korty PE, Tran DQ, et al. Expression of Helios, an Ikaros transcription factor family member, differentiates thymic-derived from peripherally induced Foxp3+ T regulatory cells. J Immunol. 2010;184:3433–3441. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0904028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zabransky DJ, Nirschl CJ, Durham NM, et al. Phenotypic and functional properties of Helios+ regulatory T cells. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e34547. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0034547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Loong CC, Hsieh HG, Lui WY, Chen A, Lin CY. Evidence for the early involvement of interleukin 17 in human and experimental renal allograft rejection. J Pathol. 2002;197:322–332. doi: 10.1002/path.1117. [Retraction in J Pathol. 2012 Oct;228(2):260; PMID: 23130366]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wagner JL, Burnett RC, Storb R. Molecular analysis of the DLA DR region. Tissue Antigens. 1996;48:549–553. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0039.1996.tb02668.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wagner JL, Burnett RC, DeRose SA, Francisco LV, Storb R, Ostrander EA. Histocompatibility testing of dog families with highly polymorphic microsatellite markers. Transplantation. 1996;62:876–877. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199609270-00032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ladiges WC, Storb R, Thomas ED. Canine models of bone marrow transplantation. Lab Anim Sci. 1990;40:11–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yu C, Ostrander E, Bryant E, Burnett R, Storb R. Use of (CA)n polymorphisms to determine the origin of blood cells after allogeneic canine marrow grafting. Transplantation. 1994;58:701–706. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hilgendorf I, Weirich V, Zeng L, et al. Canine haematopoietic chimerism analyses by semiquantitative fluorescence detection of variable number of tandem repeat polymorphism. Veterinary Research Communications. 2005;29:103–110. doi: 10.1023/b:verc.0000047486.01458.c5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Graves SS, Hogan W, Kuhr CS, et al. Stable trichimerism after marrow grafting from 2 DLA-identical canine donors and nonmyeloablative conditioning. Blood. 2007;110:418–423. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-02-071282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mathes DW, Noland M, Graves S, Schlenker R, Miwongtum T, Storb R. A preclinical canine model for composite tissue transplantation. Journal of Reconstructive Microsurgery. 2010;26:201–207. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1247717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.