Abstract

Yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae has become an attractive cell factory for production of commodity and speciality chemicals and proteins, such as industrial enzymes and pharmaceutical proteins. Here we evaluate most important expression factors for recombinant protein secretion: we chose two different proteins (insulin precursor (IP) and α-amylase), two different expression vectors (POTud plasmid and CPOTud plasmid) and two kinds of leader sequences (the glycosylated alpha factor leader and a synthetic leader with no glycosylation sites). We used IP and α-amylase as representatives of a simple protein and a multi-domain protein, as well as a non-glycosylated protein and a glycosylated protein, respectively. The genes coding for the two recombinant proteins were fused independently with two different leader sequences and were expressed using two different plasmid systems, resulting in eight different strains that were evaluated by batch fermentations. The secretion level (μmol/L) of IP was found to be higher than that of α-amylase for all expression systems and we also found larger variation in IP production for the different vectors. We also found that there is a change in protein production kinetics during the diauxic shift, i.e. the IP was produced at higher rate during the glucose uptake phase, whereas amylase was produced at a higher rate in the ethanol uptake phase. For comparison, we also refer to data from another study, in which we used the p426GPD plasmid (standard vector using URA3 as marker gene and pGPD1 as expression promoter, (Tyo KEJ, et al. Submitted)). For the IP there is more than 10 fold higher protein production with the CPOTud vector compared with the standard URA3-based vector, and this vector system therefore represent a valuable resource for future studies and optimization of recombinant protein production in yeast.

Keywords: α-amylase, Insulin precursor, Expression systems, Leader sequence, Secretory pathway, Saccharomyces cerevisiae

Introduction

Recombinant proteins include important pharmaceuticals for treatment of diseases such as diabetes or cancer, and today there are more than 200 biopharmaceuticals on the market (Walsh 2010) and new clinical studies show potentials for much wider use of recombinant proteins for treatment of other diseases (Aggarwal 2010). In order to meet the demand for recombinant proteins, there is a need for efficient expression systems with high productivity. The limitation is often in terms of obtaining sufficient quantities of recombinant proteins for clinical studies or for production at sufficiently low cost to allow for marketing (Werner 2004). Different host systems have been described, and unicellular microorganisms are often preferred because of their short generation times, high biomass yields and well-characterized manipulation/modification techniques (Porro et al. 2005).

S. cerevisiae is a well characterized eukaryal model organism for production of heterologous proteins. Contrary to bacterial host systems, S. cerevisiae possess the ability to perform post-translational modifications and secretion, which has dramatically dropped the cost of post-fermentation in vitro purification and modification (Schmidt 2004). S. cerevisiae is also more tolerant to low pH, high sugar and ethanol concentrations and high osmotic pressure, which makes it suitable for industrial fermentations (Hahn-Hägerdal et al. 2007).

It has been found that enhancement of recombinant protein secretion can be achieved by the combination of the following factors: (1) engineering of the host strains, e.g. over-expressing of genes for folding chaperones (Chigira et al. 2008; Payne et al. 2008); over-expressing of genes for trafficking proteins (Toikkanen et al. 2004) and reducing intracellular and extracellular proteolysis (Zhang et al. 2001); (2) engineering DNA sequences and expression systems, e.g. modifying protein coding sequences (Kim et al. 2006; Zhang et al. 2003) and signal sequences (Li et al. 2002; Rakestraw et al. 2009)); optimizing expression systems (increasing plasmid copy numbers (Finnis et al., XXII International Conference on Yeast Genetics & Molecular Biology) and gene expression efficiencies (Fama et al. 2007; Hackel et al. 2006); and (3) optimizing the environmental/cultivation conditions (Homma et al. 2003). Different proteins differ significantly in both their folding behaviors and amino acid demands, which lead to different levels of cell stress, and hence result in different levels of final productions. There is no one ultimate method that could work equally well for production of all proteins. Small and simple proteins could be efficiently folded faster, while multi-domain proteins could need more assistance during folding and require certain chaperones and responses to facilitate the process (Tutar and Tutar 2010). One well-studied and also very successful secretion strategy for one protein (Smith and Robinson 2002; Smith et al. 2004; Xu et al. 2005), does not always yield a promising production for another protein (Butz et al. 2003; Harmsen et al. 1996).

An additional feature should be taken into consideration when devising strategies for efficient protein secretion. The pre-pro leader sequences are very important factors that facilitate secretion of the protein product. The pre-leader is responsible for directing the peptide through the translocation step into the ER, and the pro-leader is designed to increase both the solubility of the recombinant protein (Kjeldsen et al. 1999), and the trafficking efficiency through the inter-organelle transport and vacuolar targeting (Rakestraw et al. 2009). Secretion in S. cerevisiae usually results in hyperglycosylation of the protein and leader sequences are often mutated and selected to reduce the amount of unprocessed and hyper-glycosylated proteins (Kjeldsen et al. 1998a), as well as to more efficiently direct proteins through the secretory pathway (Rakestraw et al. 2009). The leader sequence can be a native signal peptide (Bulavaite et al. 2006), a heterologous secretory peptide (Chigira et al. 2008) or a synthetic (designed) leader (Hackel et al. 2006; Rakestraw et al. 2009). For example, the alpha factor leader from S. cerevisiae, which possesses three glycosylation sites, has been proved to successfully increase protein secretion levels in several cases (Chigira et al. 2008; Robinson et al. 1994). Another efficient leader sequence is the synthetic leader Yap3-TA57 that contains no glycosylation sites and is reported to ensure a high level of secretion, in case of production of IP (Kjeldsen et al. 1999).

Vector engineering has also been extensively studied for different purposes. The marker type and promoter strength of the expression systems are key factors that determine the plasmid copy number and the mRNA level of the recombinant protein. Different marker systems (Kuroda et al. 2009) and promoter libraries (Fischer et al. 2006; Partow et al. 2010) have been made and evaluated for recombinant protein production. Toxicity genes (Agaphonov et al. 2010; Sidorenko et al. 2008), auxotrophy genes (Chigira et al. 2008; Stagoj et al. 2006), defective auxotrophy markers (Corrales-Garcia et al. 2010), and essential genes in the glycolytic pathway (Kjeldsen et al. 2002) are commonly used as selective markers. The downside of auxotrophy marker expression systems is that they have to be maintained in the synthetic medium. In contrast the POT1 expression systems have the advantage of having high plasmid stability, even when strains are cultivated in rich medium, which can generate higher cell numbers and higher protein production (Kawasaki GH, et al. 1999. US005871957A). Promoters that initiate strong and constitutive expression are often chosen for recombinant protein production: the widely used TEF1 promoter of S. cerevisiae can drive high gene expression in both high glucose conditions and glucose limited conditions (Partow et al. 2010); and the TPI1 promoter (of strongly expressed glycolytic gene TPI1 of S. cerevisiae, coding for triose phosphate isomerase), is also often used for production of recombinant proteins (Egel-Mitani et al. 2000; Kjeldsen et al. 1998b).

In order to further evaluate the process of protein-specific secretion, different types of proteins are often studied and compared using the same strategy (Rakestraw and Wittrup 2006; Robinson et al. 1996). IP and α-amylase are two widely studied proteins that we also used in our study. IP contains a 29-amino acid B chain and the normal 21-amino acid A chain of insulin connected by a mini-C chain of only 3 amino acids to ensure efficient expression (Kjeldsen et al. 1999), and it is a single chain peptide with 3 disulfide bonds and no N-glycosylation sites. α-Amylase from Aspergillus oryzae is a three-domain protein (Randez-Gil and Sanz 1993) with 478 amino acids, 4 disulfide bonds and 1 glycosylation site.

We report here the construction of eight engineered strains producing two representative recombinant proteins, IP and α-amylase, in batch cultures with diauxic shift. The engineered strains were producing either IP or α-amylase using two different secretion leaders (the native and glycosylated alpha factor leader vs. the synthetic and non-glycosylated synthetic leader Yap3-TA57), using two different promoters (TEF1 promoter and TPI1 promoter) and using a plasmid that uses the POT1 gene (from glycolytic pathway of Schizosaccharomyces pombe) as a marker (in combination with deletion of the corresponding S. cerevisiae gene in the genome). The strain with mutation in the native genomic tpi gene does not grow on glucose and the complementation with the functional copy of the heterologous TPI (in this case the POT gene from S. pombe) results in increasing the plasmid copy number in the cell, in order to sustain rapid growth on glucose. In order to show the advantage of the POT1 plasmid system, eight different POT1 derived strains were also compared with two strains in which IP and α-amylase were produced using a traditional auxotrophy plasmid-p426GPD, with URA3 marker and the GPD-promoter as expression promoter (Tyo KEJ, et al. Submitted). This study provides insights about the effect of secretion leader sequences, protein types, expression systems and promoters on heterologous protein production and secretion.

Materials and Methods

Strains and Media

Escherichia coli DH5α (Bethesda Research Laboratories) was used for plasmid constructions. The reference strain S. cerevisiae CEN. PK 530-1C (kindly provided by Peter Kötter, University of Frankfurt, Germany) was used as the yeast host for protein secretion. More information about plasmids, strains and oligonucleotide primers is provided in Table I, Table S1, Table S2 and Fig. 1.

Table I.

Strains, plasmids and peptides

| Plasmids and Strains |

Relevant Genotype | Leader | Promoter | Marker | Origin |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pspGM2 | TEF1-PGK1 bidirectional promoter (2 μm URA3) | - | - | URA3 | (Partow et al. 2010) |

| pUC57-NatInsulin | Alpha factor leader insulin synthesized | Alpha factor | - | - | (GenScript Co.) |

| pUC57Yap3Insulin | Synthetic leader insulin synthesized | Yap3-TA57 | - | - | (GenScript Co.) |

| CEN.PK 530-1C |

MATα URA3HIS3 LEU2 TRP1 SUC2 MAL2-8c tpi1(41-

707)::loxP-KanMX4-loxP |

- | - | - | SRD GmbHa |

| S. pombe L972 | h- | - | - | - | (Alao et al. 2009) |

| NC | CEN.PK 530-1C with CPOTud | - | TPI | POT1 | This study |

| AIP | CEN.PK 530-1C with pAlphaInsPOT | Alpha factor | TEF1 | POT1 | This study |

| SIP | CEN.PK 530-1C with pSynInsPOT | YAP3-TA57 | TEF1 | POT1 | This study |

| AAP | CEN.PK 530-1C with pAlphaAmyPOT | Alpha factor | TEF1 | POT1 | This study |

| SAP | CEN.PK 530-1C with pSynAmyPOT | YAP3-TA57 | TEF1 | POT1 | This study |

| AIC | CEN.PK 530-1C with pAlphaInsCPOT | Alpha factor | TPI | POT1 | This study |

| SIC | CEN.PK 530-1C with pSynInsCPOT | YAP3-TA57 | TPI | POT1 | This study |

| AAC | CEN.PK 530-1C with pAlphaAmyCPOT | Alpha factor | TPI | POT1 | This study |

| SAC | CEN.PK 530-1C with pSynAmyCPOT | YAP3-TA57 | TPI | POT1 | This study |

Scientific Research and Development GmbH, Oberursel, Germany

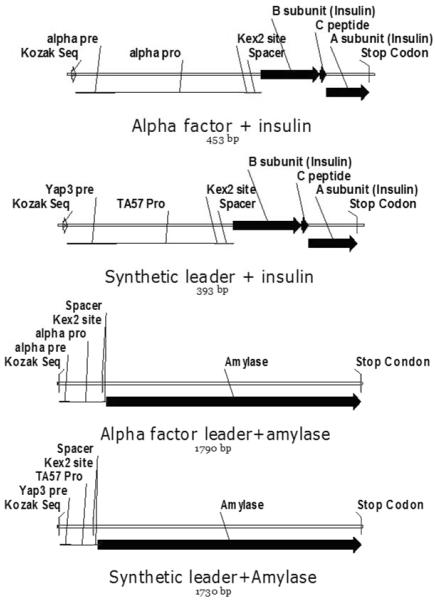

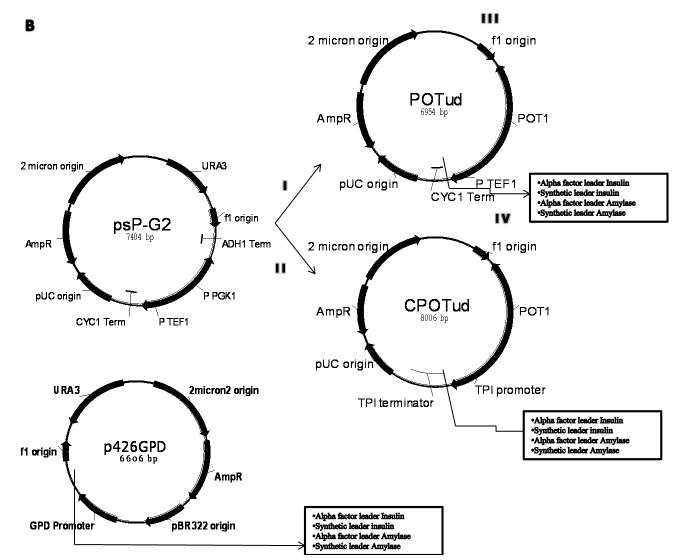

Figure 1.

Construction of recombinant vectors for production of PI and α-amylase. (A) Structure of synthesized insulin cassettes and α-amylase casettes. (B) Overview of plasmid constructions. (I) from psP-G2 to POTud plamid-PGK1 promoter and ADH1 terminator were replaced by POT1 gene with its own promoter and terminator and URA3 cassette was deleted; (II) from POTud to CPOTud plasmid-TEF1 promoter and CYC1 terminator were replaced by TPI1 promoter and terminator; (III) separately insert four different genes into POTud vector between TEF1 promoter and CYC1 terminator to generate four new plasmids; (IV) separately insert four different genes into CPOTud vector between TPI1 promoter and terminator to generate four new plasmids. (Light): psP-G2 plasmid backbone; (Dark): new fragments compared to psP-G2 plasmid.

YPD media was prepared as follows: 20 g/L D-glucose, 10 g/L Yeast extract, 20 g/L peptone and 1 g/L BSA.

Plasmid construction

We inserted the KOZAK sequence (aacaaa) (Fujikawa et al. 1986) before the secretion leader to increase the translation efficiency in S. cerevisiae (Fig. 1A and Table S2); a Kex2 site (aaaaga) (Achstetter and Wolf 1985) and a spacer (gaagaaggtgaaccaaaa) (Kjeldsen et al. 1996) between the leader and the protein coding sequence were used to increase cleavage efficiencies of the pro-leaders in the late secretory pathway; and a mini-C-peptide (Kjeldsen et al. 2002) between the insulin A-chain and B-chain was used to increase the expression level of IP.

The alpha factor leader and the synthetic leader fused with the insulin cassette, carried by pUC57-NativeInsulin and pUC57-Yap3Insulin plasmid, respectively, were synthesized by GenScript, USA. The alpha factor leader fused with insulin cassette, the synthetic leader fused with insulin cassette and the synthetic leader fused with amylase cassette were amplified from plasmid pUC57-NativeInsulin, pUC57-Yap3Insulin and pYapAmy (Tyo KEJ, et al. Submitted) using primers lzh040-lzh045, lzh043-lzh045 and lzh043-lzh044, respectively. The alpha factor leader was amplified from plasmid pUC57-NativeInsulin using primers lzh016-lzh040. The cDNA of α-amylase was amplified from plasmid pYapAmy using primers lzh018-lzh044. The alpha factor fused with the amylase cassette was constructed by fusion PCR of the alpha factor leader with the amplified amylase using primers lzh040-lzh044.

The plasmid POT was constructed by ligation of the FseI/AscI digested pSP-G2 (Partow et al. 2010) and the POT1 cassette, which was amplified from the genomic DNA of Schizosaccharomyces pombe (Alao et al. 2009) using primers lzh031-lzh032. Plasmid POTud was derived by ligating the PstI/AscI digested POT vector and the f1 origin, which was amplified from plasmid pSP-G2 using primers lzh046-lzh047. The TPI promoter and TPI terminator were purified from genomic DNA of S. cerevisiae CEN.PK 113-7D by primers lzh027-lzh028 and lzh029-lzh030, respectively, and were then ligated together after digested with NheI. The CPOTud plasmid was derived from POTud by replacing the TEF1 promoter and CYC1 terminator with the TPI promoter and terminator using restriction cites of FseI and MluI. All the IP and amylase cassettes were cloned separately with the KpnI/NheI digested POTud and CPOTud, resulted in plasmids harboring alpha factor leader insulin (pAlphaInsPOT or pAlphaInsCPOT), synthetic leader insulin (pSynInsPOT or pSynInsCPOT), alpha factor leader amylase (pAlphaAmyPOT or pAlphaAmyCPOT), or synthetic leader amylase (pSynAmyPOT or pSynAmyCPOT), respectively.

CEN.PK530-1C was transformed separately with the POTud or CPOTud derived plasmids, and resulted in different engineered strains (Fig. 1 and Table I): strain AIP (with pAlphaInsPOT), SIP (with pSynInsPOT), AAP (with pAlphaAmyPOT), SAP (with pSynAmyPOT), AIC (with pAlphaInsCPOT), SIC (with pSynInsCPOT), AAC (with pAlphaAmyCPOT) and SAC (with pSynAmyCPOT). Blank plasmid CPOTud was also transformed to CEN.PK530-1C as the negative control (strain NC). For strains nomenclature see table I.

Procedures for fermentation and analytics are described in supplementary text S1.

Results and Discussion

Construction of recombinant S. cerevisiae strains

Three expression systems were evaluated in this study (Fig. 1B): POTud, CPOTud and P426GPD. POTud and CPOTud are vectors that use the POT1 gene from S. pombe as marker to complement the tpi1 mutation in the host. TPI1 is a critical gene in both glycolysis and gluconeogenesis: A tpi1Δ strain do not grow on glucose as the sole carbon source (Compagno et al. 2001) and grow very slowly on other carbon sources (Kawasaki GH, et al. 1999. US005871957A). The tpi1Δ strain containing POT1 plasmid therefore allow stable expression in rich media (such as YPD) and also have a very high plasmid stability (Carlsen et al. 1997). In order to show the advantage of the POT1 plasmid series, we also compared them to our previous studies (Tyo KEJ, et al. Submitted) in which we used the classic auxotrophy plasmid P426GPD, which is a 2μ plasmid carrying the URA3 marker, the GPD promoter and the CYC1 terminator. Strain WI produced insulin precursor using the p426GPD plasmid and strain WA produced amylase using the p426GPD plasmid, table I.

Overall strain characterization

Recombinant protein secretion leads to changes in the cellular metabolism and extracellular fluxes and cell growth parameters were therefore different among the strains, Table S3. The CPOTud strain series grew slightly slower in the glucose phase than the other strains, which suggested significant perturbations to the growth process, but still the final biomass concentration of the different strains were comparable.

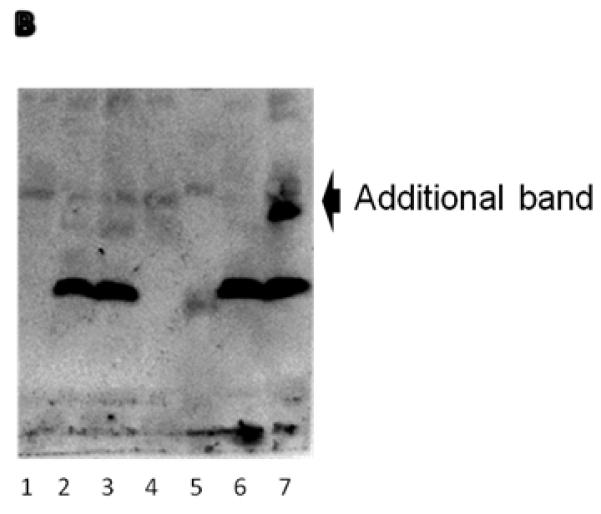

In order to demonstrate the specific binding of the insulin antibody used for the Elisa measurement, AIC and SIC strains were cultivated in shake flasks and samples at three different time points (Ts-inoculation, Tg-during diauxic shift and Tf-final titers) were tested using Western blot. Fig. 2 showed that SIC produced higher amount of insulin than AIC. Western blot also showed one additional band that corresponds to a 9 kDa (the IP band corresponds to 6 kDa) in the SIC strain (Fig. 2 WB #7). The protein associated with this band was not produced by the NC strain and it was also not present in the culture media (data not shown), and we assume that it is an insulin variant, possibly the un-efficiently cleaved pro-insulin precursor that by calculation should be 11.4 kDa (104 amino acids). This result is consistent with the HPLC measurement for another strain using the same leader (WI) (Tyo KEJ, et al. Submitted), and it may be due to the use of a synthetic leader.

Figure 2.

Confirmation of insulin precursor synthesis by Western blot using goat polyclonal antibody sc7839 and donkey anti-goat horseradish peroxidase (HRP) secondary antibody sc2033 (Santa cruz, USA). (A) Sample summaries. (B) Western blot figure showed additional band of the insulin variant. Abbreviations: Ts (the sample after inoculation), Tg (the sample by the end of the glucose phase), Tf (the sample by the end of the fermentation), AIC (the strain with pAlphaInsCPOT plasmid), SIC (the strain with pSynInsCPOT plasmid). Spectra multicolor low rang protein ladder was used in here.

Leader sequences affect recombinant protein secretion

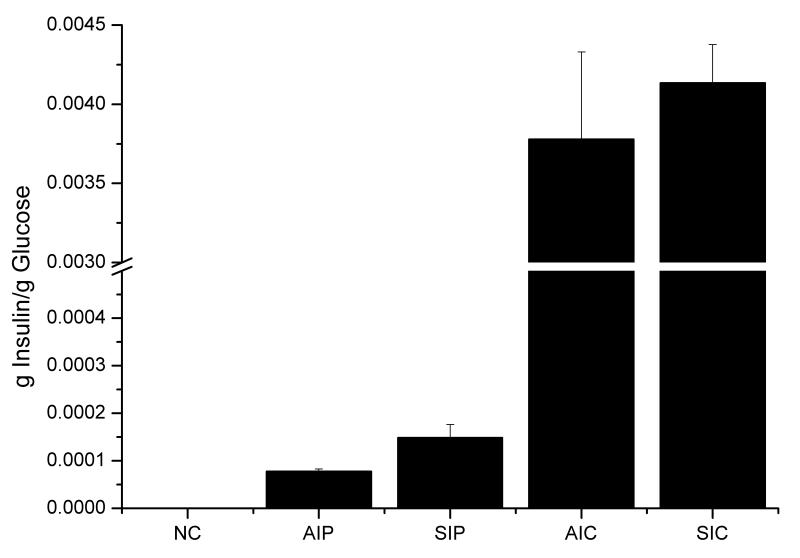

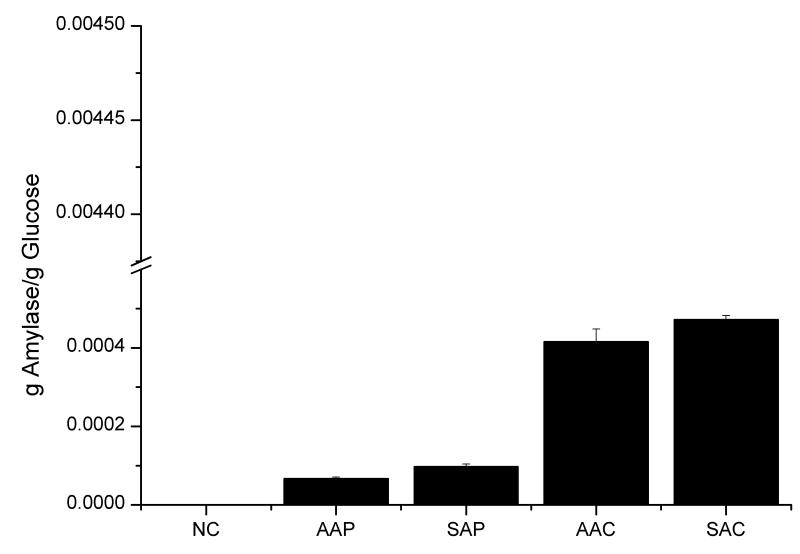

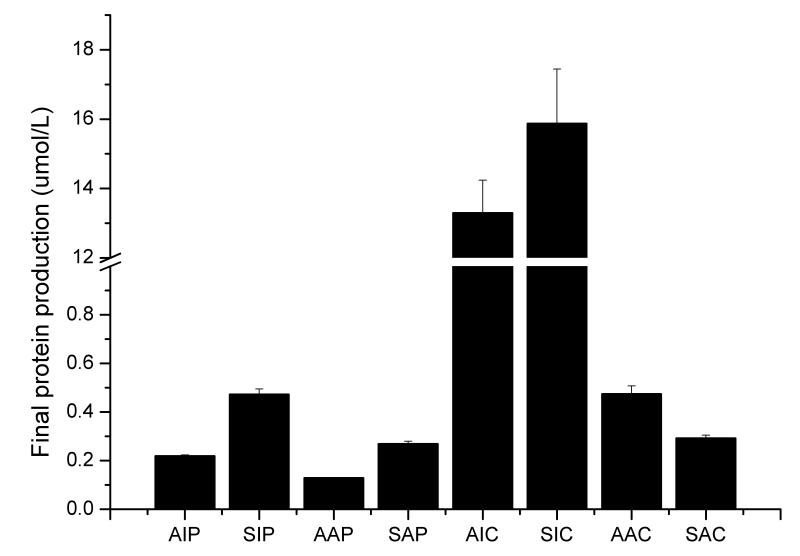

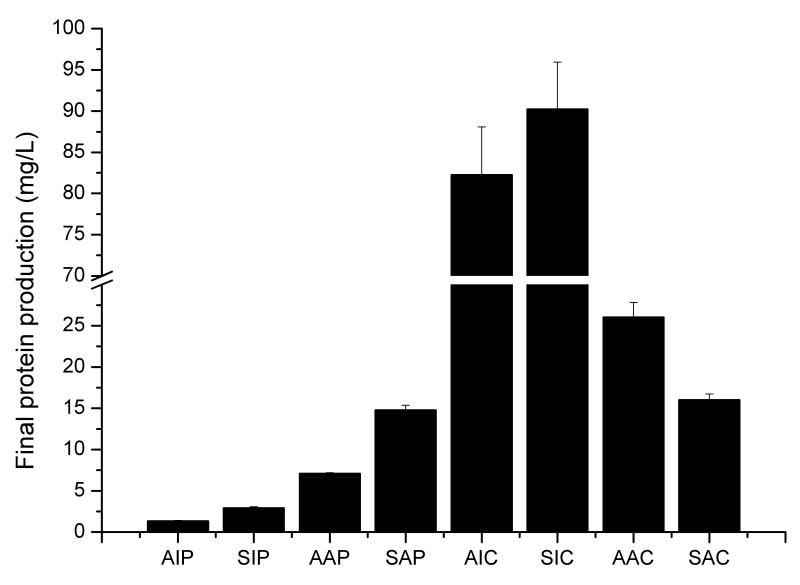

Two different leader sequences (alpha factor leader and synthetic leader) resulted in different effects on IP and amylase production both in glucose phase (Fig. 3) and in final production (Fig. 4). In all cases, the synthetic leader could direct more IP through the secretory pathway throughout the glucose and ethanol phases during the fermentation: i) in POTud derived strains, SIP produced 55% more IP than AIP in the glucose phase and had a 110% higher final titer, ii) in CPOTud derived strains, SIC could produce 9% more IP than AIC and had a 19% higher final titer and iii) in p426GPD derived strains, WI produced 15% more IP than AIG (72h shake flask, data not shown). The synthetic leader showed also an advantage for production of α-amylase but only in the strains secreting a moderate amount (around 15 mg/L in YPD medium) of α-amylase: i) in the POTud derived strains, SAP produced 36% more amylase than AAP in the glucose phase and had a 110% higher final titer; and ii) in p426GPD derived strains, strain WA produce 90% more amylase than AAG (strain with alpha factor leader fused with amylase in p426GPD plasmid, 72h shake flask, data not shown). In the strains with higher production of amylase, the synthetic leader was less advantageous: in the CPOTud derived strains, the synthetic leader strain SAC could only produce 11% more amylase than the alpha factor leader strain AAC in the glucose phase, and additionally it also had a 58% of the final titer.

Figure 3.

Protein yields in the glucose phase. (A) Insulin producing strains. (B) α-amylase producing strains. Error bars are based on independent duplicate experiments. Abbreviations: NC (the strain with CPOTud plasmid), AIP (the strain with pAlphaInsPOT plasmid), SIP (the strain with pSynInsPOT plasmid), AIC (the strain with pAlphaInsCPOT plasmid), SIC (the strain with pSynInsCPOT plasmid), WA (the strain with the synthetic-leader-amylase plasmid), AAP (the strain with pAlphaAmyPOT plasmid), SAP (the strain with pSynAmyPOT plasmid), AAC (the strain with pAlphaAmyCPOT plasmid), SAC (the strain with pSyntheticAmyCPOT plasmid).

Figure 4.

Final protein production results. (A) Final protein productions for all strains, in μmol/l. (B) Final protein productions for all strains in mg/L. Error bars are based on independent duplicate experiments.

The effect of leader sequences on different proteins could be explained by the difference of N-glycosylation sites in the pro-leader sequence. Kjeldsen et al. reported that, under stressed conditions (such as treatment with DTT), the fusion of insulin and TA39 (pro-leader with two glycosylation sites) could be transported into late Golgi compartment, while fusion of insulin and TA57 (pro-leader with no glycosylation site) was still retained in the ER (Kjeldsen et al. 1999). They conclude that the lack of N-linked glycosylations of the leader sequence would cause more protein aggregation and precipitation under stressed conditions. In our experiments, amylase is a larger and more complex protein, which may cause the protein folding to become the rate-limiting step in the secretion process. When high amount of amylase is produced, the mis-folded proteins would cause cell stress, possibly in a similar way of low-level DTT induction in the Kjeldsen’s study (Kjeldsen et al. 1999). Under this condition, the alpha factor pro-leader which possesses three glycosylation sites provides more stringent guiding for correct fold and consequently, secretion. This may not be the case with folding of IP, which seems to cause only minor ER stress, probably due to its smaller size and simpler folding. In this case the synthetic leader showed its advantage, which is consistent with a previous study (Kjeldsen et al. 1999).

Expression systems affect recombinant protein secretion

The CPOTud strain series showed a notable advantage for production of both IP and α-amylase, compared with the POTud and p426GPD derived strains through different phases during the fermentation. The advantage was more prominent for the production of IP than for the production of α-amylase. IP producing strain with the synthetic leader and CPOTud expression system, SIC, could produce 26.8-fold more IP than SIP (same construct but with POTud expression system) in the glucose phase and had a 32.5-fold higher final titer. Furthermore, SIC produced 26.6-fold more IP than WI (the synthetic leader fused insulin precursor produced with auxotrophy p426GPD system) in the glucose phase and had a 10.7-fold higher final titer. IP producing strain with the alpha factor leader and the CPOTud expression system, AIC, had a 47.3-fold higher production of IP compared with AIP (same construct but with POTud expression system) in glucose phase and it had a 59.3-fold higher final titer. For the α-amylase producing strains, the results were a bit different. The CPOTud strain series could still produce more amylase in the glucose phase (Fig. 3B): i.e. the synthetic leader strain SAC could produce 3.81-fold more amylase than SAP and 4.79-fold more amylase than WA; and the alpha factor leader strains AAC could produce 6.29-fold more amylase than AAP. However, when it comes to final titers (Fig. 4B), the AAC could produce 2.67-fold amylase than AAP, but the synthetic-leader-CPOTud strain series did not possess notable advantages: i.e. SAC produce 8% more amylase than SAP, but 3% less amylase than WA.

As an essential gene marker, POT1 is reported to yield a higher copy number than auxotrophic markers (Kawasaki GH, et al. 1999. US005871957A). Different effects of expression systems on protein production and secretion could be due to specific characteristics of the expressed protein itself. The rate limiting step for IP secretion is probably not the folding of the protein (Kjeldsen et al. 1999) but rather the IP synthesis (transcription and translation) and thus can be circumvented by increasing transcription. This is probably the cause of higher production with the CPOTud system than with p426GPD systems evaluated. For the structurally more demanding protein, such as the α-amylase, the bottleneck for secretion is likely to be post-translational processing, especially folding in the ER, and by increasing the expression with the CPOTud system more translocated peptides to the ER cause more severe mis-folding stress and more futile cycles of protein generation and degradation which in turn cause increased cell stress, such as induction of ERAD or vacuolar-localized protein degradation (Tyo KEJ, et al. Submitted). As a result protein production is even lower for some conditions. Cases with similar opposite effects have been reported before: both secretion of human parathyroid hormone (hPTH, 84 amino acids, 1 disulfide bond and 0 glycosylation sites) (Gabrielsen et al. 1990) or granulocyte-colony stimulating factor (GCSF, 174 amino acids, 2 disulfide bonds and 0 glycosylation sites) (Wittrup et al. 1994) had increased production 17-fold by using a multi-copy plasmid compared to the a single copy plasmid; whereas for secretion of S. pombe acid phosphatase (PHO, 435 amino acids, 8 disulfide bonds and 9 glycosylation sites), the use of a multi-copy plasmid resulted in a 24% decrease in secretion when compared to a single copy plasmid (Robinson et al. 1994). From these studies as well as our results, we suggest that the limitations are dependent on the molecular weight, and also the complexity of the protein (disulphide bonds, glycosylations, multi-domains, etc). Since secretion of glycosylated proteins in S. cerevisiae is often reduced due to hyper-glycosylation and mis-folding inside the cell (Srivastava et al. 2001), the number of the glycosylation sites in the leader sequence is another very important factor to consider.

Despite large variations in protein secretion capacity in the strains evaluated here it is interesting to note that the only difference between the POTud and CPOTud plasmids is the promoter that drives the heterologous protein expression. It has been found that the TEF1 promoter is stronger than the TPI1 promoter using lacZ as the reporter gene, both in conditions of glucose excess (1.67-fold compared to TPI promoter) or limitation (5-fold compared to TPI promoter) (Partow et al. 2010). Interestingly, the final protein expression of either IP or amylase from the plasmid including the TEF1 promoter was lower. qPCR assays were therefore performed to compare relative gene expression levels in the yeast strains transformed with the expression systems including either the TPI1 promoter (AIC and AAC strains respectively) or the TEF1 promoter (AIP and AAP strains), as described in Table 1. The relative transcript levels corresponding to both the IP and amylase genes controlled by the TEF1 promoter were indeed higher than those controlled by the TPI promoter (Figure S3). These results, which are consistent with previously reports (Partow et al. 2010) on the relative strength of these two promoters, suggest that the choice of promoter is not directly influencing the final protein titer in the POT1 derived strains. Thus, other events regarding post-transcriptional regulation might be involved and therefore affecting protein production. A follow-up experiment regarding global transcriptional analysis with amylase producing strains (AAP and AAC strains) was performed (data not shown). Using a integrated analysis, we found that among the top 10 significant Reporter TFs (FDR<0.005), genes related to transcription regulation (RAP1) and RNA stability (CCR4, (Berretta et al. 2008)) were both up-regulated in the AAC strain. These data suggest that although the TEF1p has higher transcriptional levels, the RNA degradation is also higher and the difference regarding protein production could relate to differences in the RNA turnover. It is suggested that the expression rate of recombinant proteins may be restricted by a high RNA turn-over rate (Schmidt 2004), and the yield could possible be increased substantially by increasing the translation efficiency (Romanos et al. 1991).

Comparison of insulin precursor and α-amylase secretion

Secretion profiles of IP and α-amylase producing strains were also examined (Fig. 4). Based on this it was found that the trend for production of IP and α-amylase in terms of mg/L is not conserved in the different constructs, whereas in terms of μmol/L the production of IP is always higher. In order to explain the high transcriptional level and the relatively low protein production of amylase producing strain, a follow-up experiment regarding global transcriptional analysis of the amylase producing strain (AAC and NC strains) was performed (data not shown). Using integrated analysis, we found that among the significant Reporter GO-terms (FDR<0.001), many pathways related to the overall transcription and translation were down-regulated in the AAC strain, whereas GO-terms associated with ER protein processing, vacuole degradation, stress response and unfolded protein response were up-regulated. Within the top 10 significant Reporter TFs (FDR<0.005), genes related to all kinds of stress (MSN2 and MSN4 for general stress, HOG1 for osmotic stress and YAP1 for oxidative stress) and heat shock factor which could release ER stress (HSF1) were up-regulated in the AAC strain. All these data suggest that in the amylase producing strains, the high amount of recombinant proteins or peptides are blocking the secretory pathway (possibly inside of the ER) which causes cell stress including the unfolded protein response. The result of this is down-regulation of the general transcription and translation machinery and up-regulation of the ER processing and protein turnover pathways.

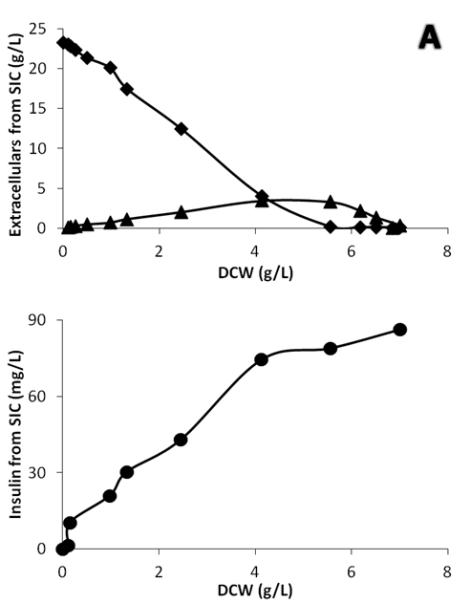

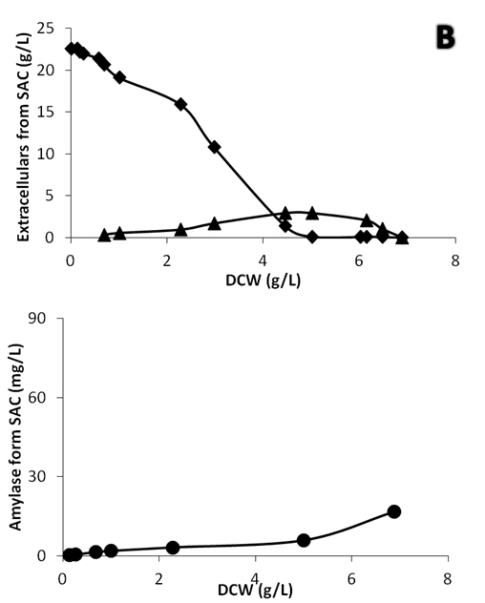

In addition to their final titers, the IP and α-amylase also differ in their processing characteristics in the secretory pathway. By plotting the protein production data against dry cell weight to eliminate the effect of the changing cell concentration, it is found that there is a clear shift in the secretion behavior during the diauxic shift (Fig. 5). Interestingly, all α-amylase producing strains produced amylase at a higher rate during growth in ethanol phase, whereas all IP producing strains produced IP at a higher rate in the glucose phase. The shifting patterns of protein productions further supported the fact that the rate-controlling step for protein secretion is different between the two proteins. As mentioned above, production of the IP is probably mainly limited by expression and for all the used expression promoters (pTPI1, pTEF1 and pGPD1) there is higher expression for high growth/high glycolytic fluxes. For amylase, which is a larger protein with more diverse modifications, the limitation is likely to be protein processing and folding. We hypothesize that the respiratory conditions prevailing during growth on ethanol may have a beneficial effect on the folding process (compared with the fermentative conditions prevailing in the glucose growth phase). The conversion of ethanol into acetaldehyde requires NAD(P) as cofactors (Visser et al. 2004), and the hence elevated amount of NAD(P)H could serve as the reducing power either for reduction of ROS generated by the folding stress (Tyo KEJ, et al. Submitted) or by converting oxidized glutathione (GSSG) into reduced glytathione (GSH). GSH plays an very important role during the refolding of mis-folded proteins (Tu et al. 2000), and the shortage of GSH could lead to hyper-oxidizing conditions in the ER (Van de Laar et al. 2007), and produce more ROS through futile cycling of the folding process (Nguyen et al. 2011). There may also be a favorable heat shock-like effect induced by ethanol (Alexandre et al. 2001; Piper 1995).

Figure 5.

Secretion profiles of IP and α-amylase strains. Protein productions were plotted versus cell growth (expressed as dry cell weight, DCW) to compare single cell producing capacity. (Circle) protein production (mg/l), (Diamond) Glucose concentration (g/l) and (Triangle) Ethanol concentration (g/l). (A) IP production by strain SIC. (B) α-amylase production by strain SAC.

Conclusion

Here, we provide a novel set of expression vectors for recombinant protein production in yeast, and we used these to evaluate the most important expression factors regarding recombinant secretion: protein type, leader sequence, expression system and promoter. We report that although the transcription level of the recombinant gene is important, the final production of the recombinant protein is the result of a combination of effects of transcription and translation levels, protein uniqueness, and the leader sequences which influences the secretory pathway processing efficiency. We also report a notable difference in production of IP and α-amylase, and we conclude that this difference is caused by differences in their processing through the secretory pathway. For insulin precursor the important step is the synthesis of the protein, and this is supported by i) dramatic IP production changes between the CPOTud and p426GPD systems and ii) more and faster IP production during growth on glucose. For amylase the rate-controlling step for secretion was found to be most likely ER folding and processing as supported by i) lower secretion of the α-amylase with a synthetic leader compared to the glycosylated alpha factor leader in the high production strains, ii) much more amylase produced in AAC compared with AAP, whereas moderate changes of final protein productions iii) the dramatically increased production during growth on ethanol. Our study provides a novel insight into the protein secretion engineering in yeast, and a set of novel expression systems that can be used for high-level expression of recombinant proteins in connection with the use of yeast for consolidated bioprocesses.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

We thank Dr. Per Sunnerhagen from Gothenburg University for kindly providing the Schizosaccharomyces pombe strain and Dr. Peter Kötter from University of Frankfurt for kindly providing the CEN.PK 113-5D and CEN.PK 530-1C strains. This work is financially supported by the EU Framework VII project SYSINBIO (Grant no. 212766), European Research Council ERC project INSYSBIO (Grant no. 247013), the Chalmers Foundation, the Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation and NIH F32 Kirschstein NRSA fellowship.

Reference

- Achstetter T, Wolf D. Hormone processing and membrane-bound proteinases in yeast. EMBO J. 1985;4(1):173–177. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1985.tb02333.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agaphonov M, Romanova N, Choi E, Ter-Avanesyan M. A novel kanamycin/G418 resistance marker for direct selection of transformants in Escherichia coli and different yeast species. Yeast. 2010;27(4):189–195. doi: 10.1002/yea.1741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aggarwal S. What’s fueling the biotech engine—2009–2010. Nat Biotech. 2010;28(11):1165–1171. doi: 10.1038/nbt1110-1165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alao J, Olesch J, Sunnerhagen P. Inhibition of type I histone deacetylase increases resistance of checkpoint-deficient cells to genotoxic agents through mitotic delay. Mol Cancer Ther. 2009;8(9):2606–2615. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-09-0218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexandre H, Ansanay-Galeote V, Dequin S, Blondin B. Global gene expression during short-term ethanol stress in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. FEBS Lett. 2001;498(1):98–103. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(01)02503-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berretta J, Pinskaya M, Morillon A. A cryptic unstable transcript mediates transcriptional trans-silencing of the Ty1 retrotransposon in S. cerevisiae. Genes & Development. 2008;22(5):615–626. doi: 10.1101/gad.458008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bulavaite A, Sabaliauskaite R, Staniulis J, Sasnauskas K. Synthesis of hepatitis B virus surface protein derivates in yeast S. cerevisiae. Biologija. 2006;4(49):53. [Google Scholar]

- Butz JA, Niebauer RT, Robinson AS. Co-expression of molecular chaperones does not improve the heterologous expression of mammalian G-protein coupled receptor expression in yeast. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2003;84(3):292–304. doi: 10.1002/bit.10771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlsen M, Jochumsen KV, Emborg C, Nielsen J. Modeling the growth and proteinase A production in continuous cultures of recombinant Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biotechnol Bioeng. 1997;55(2):447–454. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0290(19970720)55:2<447::AID-BIT22>3.0.CO;2-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chigira Y, Oka T, Okajima T, Jigami Y. Engineering of a mammalian O-glycosylation pathway in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae: production of O-fucosylated epidermal growth factor domains. Glycobiology. 2008;18(4):303–314. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwn008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compagno C, Brambilla L, Capitanio D, Boschi F, Ranzi B Maria, Porro D. Alterations of the glucose metabolism in a triose phosphate isomerase-negative Saccharomyces cerevisiae mutant. Yeast. 2001;18(7):663–670. doi: 10.1002/yea.715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrales-Garcia L, Possani L, Corzo G. Expression systems of human β-defensins: vectors, purification and biological activities. Amino Acids. 2010:1–9. doi: 10.1007/s00726-010-0493-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egel-Mitani M, Andersen AS, Diers I, Hach M, Thim L, Hastrup S, Vad K. Yield improvement of heterologous peptides expressed in yps1-disrupted Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains. Enzyme Microb Tech. 2000;26(9-10):671–677. doi: 10.1016/s0141-0229(00)00158-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fama MC, Raden D, Zacchi N, Lemos DR, Robinson AS, Silberstein S. The Saccharomyces cerevisiae YFR041C/ERJ5 gene encoding a type I membrane protein with a J domain is required to preserve the folding capacity of the endoplasmic reticulum. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007;1773(2):232–242. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2006.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer C, Alper H, Nevoigt E, Jensen K, Stephanopoulos G. Response to Hammer et al. Tuning genetic control--importance of thorough promoter characterization versus generating promoter diversity. Trends Biotechnol. 2006;24(2):55–56. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2005.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujikawa K, Chung D, Hendrickson L, Davie E. Amino acid sequence of human factor XI, a blood coagulation factor with four tandem repeats that are highly homologous with plasma prekallikrein. Biochemistry. 1986;25(9):2417–2424. doi: 10.1021/bi00357a018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabrielsen O, Reppe S, S ther O, Blingsmo O, Sletten K, Gordeladze J, H gset A, Gautvik V, Alestr m P, yen T. Efficient secretion of human parathyroid hormone by Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Gene. 1990;90(2):255–262. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(90)90188-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hackel BJ, Huang D, Bubolz JC, Wang XX, Shusta EV. Production of soluble and active transferrin receptor-targeting single-chain antibody using Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Pharm Res. 2006;23(4):790–797. doi: 10.1007/s11095-006-9778-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn-Hägerdal B, Karhumaa K, Fonseca C, Spencer-Martins I, Gorwa-Grauslund M. Towards industrial pentose-fermenting yeast strains. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2007;74(5):937–953. doi: 10.1007/s00253-006-0827-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harmsen MM, Bruyne MI, Rau HA, Maat J. Overexpression of binding protein and disruption of the PMR1 gene synergistically stimulate secretion of bovine prochymosin but not plant Thaumatin in yeast. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1996;46(4):365–370. doi: 10.1007/BF00166231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Homma T, Iwahashi H, Komatsu Y. Yeast gene expression during growth at low temperature. Cryobiology. 2003;46(3):230–237. doi: 10.1016/s0011-2240(03)00028-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim YS, Bhandari R, Cochran JR, Kuriyan J, Wittrup KD. Directed evolution of the epidermal growth factor receptor extracellular domain for expression in yeast. Proteins. 2006;62(4):1026–1035. doi: 10.1002/prot.20618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kjeldsen T, Brandt J, Andersen AS, Egel-Mitani M, Hach M, Pettersson AF, Vad K. A removable spacer peptide in an α-factor-leader/insulin precursor fusion protein improves processing and concomitant yield of the insulin precursor in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Gene. 1996;170(1):107–112. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00822-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kjeldsen T, Pettersson A Frost, Hach M. The role of leaders in intracellular transport and secretion of the insulin precursor in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biotechnol. 1999;75(2-3):195–208. doi: 10.1016/s0168-1656(99)00159-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kjeldsen T, Hach M, Balschmidt P, Havelund S, Pettersson A, Markussen J. Prepro-leaders lacking N-linked glycosylation for secretory expression in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Protein Expres and Purif. 1998a;14(3):309–316. doi: 10.1006/prep.1998.0977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kjeldsen T, Ludvigsen S, Diers I, Balschmidt P, Sorensen AR, Kaarsholm NC. Engineering-enhanced protein secretory expression in yeast with application to insulin. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(21):18245–18248. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C200137200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kjeldsen T, Pettersson AF, Drube L, Kurtzhals P, Jonassen I, Havelund S, Hansen PH, Markussen J. Secretory expression of human albumin domains in Saccharomyces cerevisiae and their binding of myristic acid and an acylated insulin analogue. Protein Expres Purif. 1998b;13(2):163–169. doi: 10.1006/prep.1998.0876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuroda K, Matsui K, Higuchi S, Kotaka A, Sahara H, Hata Y, Ueda M. Enhancement of display efficiency in yeast display system by vector engineering and gene disruption. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2009;82(4):713–719. doi: 10.1007/s00253-008-1808-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Xu H, Bentley WE, Rao G. Impediments to secretion of green fluorescent protein and its fusion from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biotechnol Prog. 2002;18(4):831–838. doi: 10.1021/bp020066t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen VD, Saaranen MJ, Karala A-R, Lappi A-K, Wang L, Raykhel IB, Alanen HI, Salo KEH, Wang C-c, Ruddock LW. Two Endoplasmic Reticulum PDI Peroxidases Increase the Efficiency of the Use of Peroxide during Disulfide Bond Formation. J Mol Biol. 2011;406(3):503–515. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.12.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Partow S, Siewers V, Bj rn S, Nielsen J, Maury J. Characterization of different promoters for designing a new expression vector in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast. 2010;27(11):955–964. doi: 10.1002/yea.1806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Payne T, Finnis C, Evans LR, Mead DJ, Avery SV, Archer DB, Sleep D. Modulation of chaperone gene expression in mutagenised S. cerevisiae strains developed for rHA production results in increased production of multiple heterologous proteins. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2008;74(24):7759–7766. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01178-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piper P. The heat shock and ethanol stress responses of yeast exhibit extensive similarity and functional overlap. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1995;134(2-3):121–127. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1995.tb07925.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porro D, Sauer M, Branduardi P, Mattanovich D. Recombinant protein production in yeasts. Mol Biotechnol. 2005;31(3):245–259. doi: 10.1385/MB:31:3:245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rakestraw A, Wittrup KD. Contrasting secretory processing of simultaneously expressed heterologous proteins in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biotechnol and Bioeng. 2006;93(5):896–905. doi: 10.1002/bit.20780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rakestraw JA, Sazinsky SL, Piatesi A, Antipov E, Wittrup KD. Directed evolution of a secretory leader for the improved expression of heterologous proteins and full-length antibodies in S. cerevisiae. Biotechnol and Bioeng. 2009;103(6):1192–1201. doi: 10.1002/bit.22338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Randez-Gil F, Sanz P. Expression of Aspergillus oryzae α-amylase gene in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1993;112(1):119–124. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1993.tb06433.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson AS, Bockhaus JA, Voegler AC, Wittrup KD. Reduction of BiP Levels Decreases Heterologous Protein Secretion in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biol Chem. 1996;271(17):10017–10022. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.17.10017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson AS, Hines V, Wittrup KD. Protein disulfide isomerase overexpression increases secretion of foreign proteins in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Bio/Technology. 1994;12(4):381–384. doi: 10.1038/nbt0494-381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romanos MA, Makoff AJ, Fairweather NF, Beesley KM, Slater DE, Rayment FB, Payne MM, Clare JJ. Expression of tetanus toxin fragment C in yeast: gene synthesis is required to eliminate fortuitous polyadenylation sites in AT-rich DNA. Nucleic acids research. 1991;19(7):1461–1467. doi: 10.1093/nar/19.7.1461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt F. Recombinant expression systems in the pharmaceutical industry. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2004;65(4):363–372. doi: 10.1007/s00253-004-1656-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sidorenko Y, Antoniukas L, Schulze-Horsel J, Kremling A, Reichl U. Mathematical model of growth and heterologous hantavirus protein production of the recombinant yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Eng Life Sci. 2008;8(4):399–414. [Google Scholar]

- Smith JD, Robinson AS. Overexpression of an archaeal protein in yeast: secretion bottleneck at the ER. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2002;79(7):713–723. doi: 10.1002/bit.10367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith JD, Tang BC, Robinson AS. Protein disulfide isomerase, but not binding protein, overexpression enhances secretion of a non-disulfide-bonded protein in yeast. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2004;85(3):340–350. doi: 10.1002/bit.10853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava A, Piskur J, Nielsen J, Egel-Mitani M. Method for the production of heterologous polypeptides in transformed yeast cells. 6,190,883 B1 patent US. 2001

- Stagoj MN, Comino A, Komel R. A novel GAL recombinant yeast strain for enhanced protein production. Biomol Eng. 2006;23(4):195–199. doi: 10.1016/j.bioeng.2006.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toikkanen JH, Sundqvist L, Keranen S. Kluyveromyces lactis SSO1 and SEB1 genes are functional in Saccharomyces cerevisiae and enhance production of secreted proteins when overexpressed. Yeast. 2004;21:1045–1055. doi: 10.1002/yea.1151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tu B, Ho-Schleyer S, Travers K, Weissman J. Biochemical basis of oxidative protein folding in the endoplasmic reticulum. Science. 2000;290(5496):1571. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5496.1571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tutar L, Tutar Y. Heat shock proteins; an overview. Current Pharmaceutical Biotechnology. 2010;11(2):216–222. doi: 10.2174/138920110790909632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van de Laar T, Visser C, Holster M, López C, Kreuning D, Sierkstra L, Lindner N, Verrips T. Increased heterologous protein production by Saccharomyces cerevisiae growing on ethanol as sole carbon source. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2007;96(3):483–494. doi: 10.1002/bit.21150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visser D, van Zuylen G, van Dam J, Eman M, Pr ll A, Ras C, Wu L, van Gulik W, Heijnen J. Analysis of in vivo kinetics of glycolysis in aerobic Saccharomyces cerevisiae by application of glucose and ethanol pulses. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2004;88(2):157–167. doi: 10.1002/bit.20235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh G. Biopharmaceutical benchmarks 2010. Nat Biotech. 2010;28(9):917–924. doi: 10.1038/nbt0910-917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werner R. Economic aspects of commercial manufacture of biopharmaceuticals. J Biotechnol. 2004;113(1-3):171–182. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2004.04.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittrup K, Robinson A, Parekh R, Forrester K. Existence of an optimum expression level for secretion of foreign proteins in yeast. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1994;745(1):321–330. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1994.tb44385.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu P, Raden D, Doyle FJ, Robinson AS. Analysis of unfolded protein response during single-chain antibody expression in Saccaromyces cerevisiae reveals different roles for BiP and PDI in folding. Metab Eng. 2005;7(4):269–279. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2005.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang B, Chang A, Kjeldsen TB, Arvan P. Intracellular retention of newly synthesized insulin in yeast is caused by endoproteolytic processing in the golgi complex. J Cell Biol. 2001;153(6):1187–1198. doi: 10.1083/jcb.153.6.1187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang B, Liu M, Arvan P. Behavior in the eukaryotic secretory pathway of insulin-containing fusion proteins and single-chain insulins bearing various B-chain mutations. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(6):3687–3693. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M209474200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.