Abstract

In North America, the biomedical research community faces social and economic challenges to nonhuman primate (NHP) importation that could reduce the number of NHP available for research needs. The effect of such limitations on specific biomedical research topics is unknown. The Association of Primate Veterinarians (APV), with assistance from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, developed a survey regarding biomedical research involving NHP in the United States and Canada. The survey sought to determine the number and species of NHP maintained at APV members’ facilities, current uses of NHP to identify the types of biomedical research that rely on imported animals, and members’ perceived trends in NHP research. Of the 149 members contacted, 33 (22%) replied, representing diverse facility sizes and types. Cynomolgus and rhesus macaques were the most common species housed at responding institutions and comprised the majority of newly acquired and imported NHP. The most common uses for NHP included pharmaceutical research and development and neuroscience, neurology, or neuromuscular disease research. Preclinical safety testing and cancer research projects usually involved imported NHP, whereas research on aging or degenerative disease, reproduction or reproductive disease, and organ or tissue transplantation typically used domestic-bred NHP. The current results improve our understanding of the research uses for imported NHP in North America and may facilitate estimating the potential effect of any future changes in NHP accessibility for research purposes. Ensuring that sufficient NHP are available for critical biomedical research remains a pressing concern for the biomedical research community in North America.

Abbreviation: APV, Association of Primate Veterinarians; CDC, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; NHP, nonhuman primate

Nonhuman primates (NHP) remain key animal models for specific types of biomedical research because of their close phylogenetic relationships and physiologic similarities to humans.1,8,10,12,18 However, the use of NHP in research has become increasingly controversial such that ensuring a stable supply of NHP to meet biomedical research needs continues to be a pressing concern.4,16,23

In fiscal year 2010, US research facilities housed more than 70,000 NHP for use in biomedical research.21 Although many North American facilities rely on domestic NHP breeding colonies for research needs, they also import purpose-bred NHP, primarily from Asia, to supplement domestic breeding. NHP importation into the United States peaked in 2008 at just over 25,000 animals but has experienced a small but steady decline each subsequent year.14 Many social, economic, and scientific factors might be contributing to this decrease, for example, development of alternatives to replace NHP models. One factor of great concern to researchers is increasing resistance among airlines to transport live NHP.17,23

Only a few reports describe the types of NHP species used and the research areas in which this model predominates.3,9,20 Previous retrospective literature reviews provide valuable baseline information about NHP research activities for some species or geographic locations; however, these studies do not identify NHP procurement sources. Therefore, published literature does not identify which types of biomedical research are most reliant on imported NHP nor does it assist with understanding how changes in importation would affect the numbers of NHP available for specific biomedical research activities. A cross-sectional, survey-based approach provides more direct access to information about species use, NHP sources, and the types of studies that are most reliant on NHP importation.

The Association of Primate Veterinarians (APV), with technical support from the Division of Global Migration and Quarantine at the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), collaboratively surveyed APV's membership regarding biomedical research activities involving NHP at institutions in the United States and Canada. The goal of this survey was to document the number and species of imported NHP maintained at research facilities served by APV members, to understand the types of biomedical research that are particularly reliant on imported NHP, and to gain insight into practicing primate veterinarians’ perceptions of NHP research trends.

Materials and Methods

Participant identification.

APV estimates that it has approximately 400 members in North America, which is believed to constitute the majority of practicing primate veterinarians in the United States and Canada. These veterinarians provide and oversee health care for a wide variety of NHP species in a broad range of settings, including research facilities at major universities, National Primate Research Centers, pharmaceutical research and development facilities, facilities operated by breeders and importers of NHP for research use, and a small number of sanctuaries and zoos. Because completed surveys would not retain facility- or individual-level identifying information, APV selected a subset of the membership to receive the survey that included only one member veterinarian per institution, to prevent duplicate responses. This approach constituted a relatively complete effort to obtain information from a variety of North American institutions housing NHP for research purposes.

Survey administration.

APV and CDC jointly developed a 16-item questionnaire to survey practicing primate veterinarians about the sources and species of NHP housed at their institutions during 01 January 2010 through 31 December 2012, the types of research being conducted with these animals, and perceived trends in NHP research (the complete survey is available by request of the corresponding author). Questions concerning human occupational health and safety, animal handling, and quarantine for newly procured animals were included in the survey also, but these results will not be described here. APV emailed the survey to selected members; APV received and compiled completed surveys, removing any identifying information before providing the data to CDC for analysis. In December 2012, APV sent an initial email to respondents requesting participation in the survey and 2 reminder emails at 2-wk intervals before the close of data collection in January 2013.

Data handling and analysis.

One investigator entered all survey data into a database (Access 2010, Microsoft, Redmond, WA) and then individually checked each record by hand for entry errors. Descriptive analyses were calculated by using JMP version 10 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC), and graphics were produced in Excel 2010 (Microsoft).

Human subjects.

CDC's Institutional Review Board and the University of Guelph Research Ethics Board determined that this study did not qualify as a human subjects research project. Information collected applied only to the institution employing respondents and not to the individual completing the survey. The survey did not collect personal identifiers for the respondents or their institutions. Participants were informed by email that survey completion was voluntary, that there were no repercussions for choosing not to participate, and that all information provided in the survey would remain anonymous and would only be made public in aggregate.

Results

Description of responding facilities.

Of the 149 APV members contacted, 33 (22%) replied. Of the 33 respondents, 7 indicated that their facilities were not currently housing NHP and did not complete the rest of the survey; 26 completed surveys were included in this analysis.

Sixteen (62%) of the 26 responding facilities were university facilities, and 5 (19%) were private or contract research facilities. Four (15%) of the 26 respondents were CDC-registered NHP importers (Table 1). During the past 12 mo, 14 (54%) facilities maintained relatively small NHP populations, housing a maximum of 100 animals. Three (12%) facilities maintained an average NHP census of 2500 animals or more. Most (81%) respondents reported that 50% or more of the NHP housed at the facility were typically on active research studies at any given time (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of responding facilities (n = 26)

| No. (%) of facilities | |

| Facility typea | |

| University research | 16 (61.5%) |

| Private or contract research | 5 (19.2%) |

| National Primate Research Center | 3 (11.5%) |

| Pharmaceutical industry research | 3 (11.5%) |

| Commercial importer | 1 (3.8%) |

| Commercial breeding | 1 (3.8%) |

| CDC-registered importer of NHP? | |

| No | 22 (84.6%) |

| Yes | 4 (15.4%) |

| Average no. of NHP housed at facility during the past 12 mo | |

| 1–50 | 8 (30.8%) |

| 51–100 | 6 (23.1%) |

| 101–500 | 4 (15.4%) |

| 501–1000 | 0 (0.0%) |

| 1001–2500 | 5 (19.2%) |

| >2500 | 3 (11.5%) |

| Percentage of NHP in facility on research studies | |

| <10% | 1 (3.8%) |

| 10%–25% | 1 (3.8%) |

| 26%–50% | 3 (11.5%) |

| 51%–75% | 5 (19.2%) |

| >75% | 16 (61.5%) |

| NHP species housed at facility during the past 12 moa | |

| Rhesus macaques | 21 (80.8%) |

| Cynomolgus macaques | 19 (73.1%) |

| African green monkeys | 4 (15.4%) |

| Squirrel monkeys | 4 (15.4%) |

| Baboons | 4 (15.4%) |

| Pigtailed macaques | 3 (11.5%) |

| Capuchin monkeys | 2 (7.7%) |

| Stumptailed macaques | 1 (3.8%) |

| Titi monkeys | 1 (3.8%) |

| Marmosets | 1 (3.8%) |

Will not sum to 100% because respondents could choose more than one answer.

NHP species, procurement, and disposition.

Facilities housed 1 to 5 different NHP species, with a median of 2 species in residence. Most facilities housed at least one macaque species (genus Macaca). Of the 26 responding facilities, 21 (81%) housed rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta), 19 (73%) housed cynomolgus macaques (Macaca fascicularis), and 3 (12%) housed pigtailed macaques (Macaca nemestrina). In addition, African green monkeys (Chlorocebus aethiops), squirrel monkeys (Saimiri spp.), and baboons (Papio spp.) were maintained at a few responding institutions (Table 1).

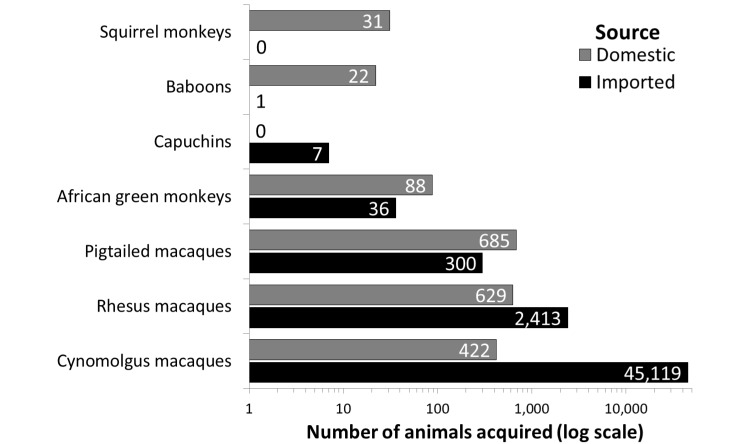

Of the 26 facilities, 23 (89%) reported that they had procured new NHP of one or more species during the 3-y period from 01 January 2010 through 31 December 2012. Multiple facilities reported procuring cynomolgus macaques and rhesus macaques during all 3 y (total number procured by year: cynomolgus macaques, 2010 = 14,971; 2011 = 15,908; 2012 = 14,662; rhesus macaques, 2010 = 878; 2011 = 1142; 2012 = 1022). During 01 January 2010 through 31 December 2012, the majority of cynomolgus macaques procured were imported, and more than 75% of newly procured rhesus macaques were imported (Figure 1). In contrast, facilities tended to procure pigtailed macaques, African green monkeys, squirrel monkeys, and baboons in relatively small numbers and typically obtained them from domestic sources (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The number of NHP acquired by responding facilities during 01 January 2010 through 31 December 2012 varies by both the species of NHP and the source from which facilities acquire new animals. Gray bars indicate NHP sourced from domestic breeders or transferred from other North American facilities. Black bars indicate the number of NHP imported from countries outside of North America.

To obtain information regarding turnover rates for NHP in research projects, respondents were asked about the disposition of NHP after the completion of research studies, reported as an estimated percentage of NHP encountering a particular disposition, including euthanasia, reassignment to another study within the facility, retirement to a sanctuary, removal to another facility for additional studies, and placement in a breeding colony. Euthanasia was the most common disposition, with 15 (58%) facilities reporting euthanasia of 80% or more of NHP at their facility upon study termination, and 17 (65%) reported euthanasia of 50% or more of these animals. Only 5 (19%) facilities reported that 80% or more of NHP were reassigned to new studies within their facility, and 7 (27%) reported that 50% or more of NHP were reassigned within their own facility. Two (8%) facilities reported retiring animals to a sanctuary at study end (100% for one facility and 75% for the other). A third facility mentioned plans to transition to majority sanctuary retirement in the near future.

Research uses for imported and domestically acquired NHP.

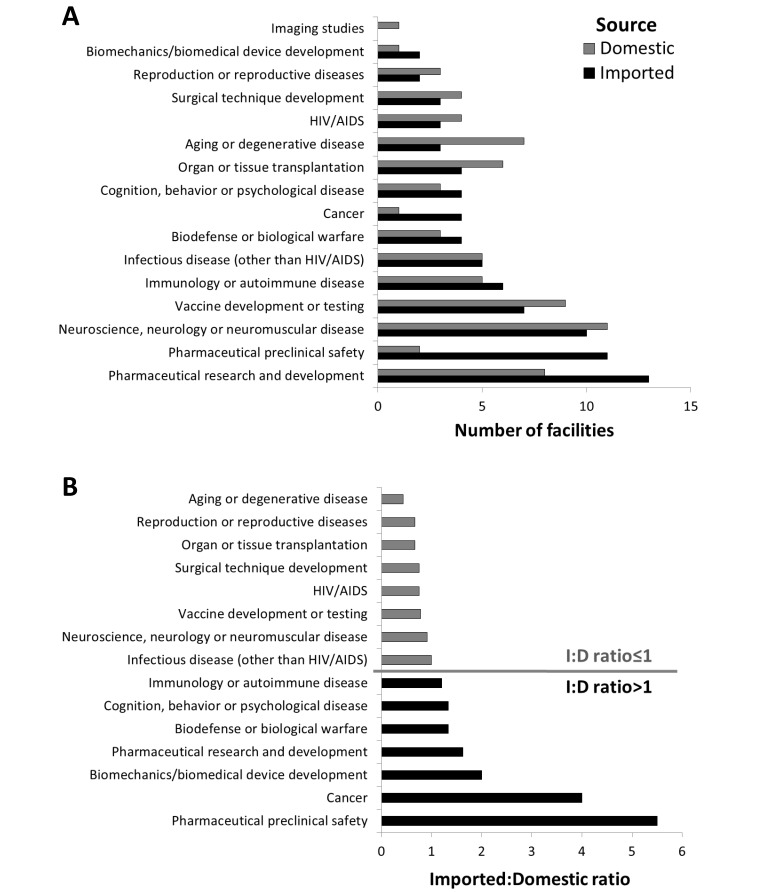

Responding facilities reported using NHP acquired from both domestic and imported sources from 01 January 2010 through 31 December 2012 in diverse research studies. The majority of facilities reported conducting studies related to pharmaceutical research and development and neuroscience, neurology or neuromuscular disease research (21 facilities, 89% for each topic). Other commonly reported study uses included vaccine development or testing (16 facilities, 62%), pharmaceutical preclinical safety research (13 facilities, 50%), and immunology or autoimmune disease research (11 facilities, 42%).

Preclinical safety testing and cancer research primarily made use of imported NHP and had imported:domestic ratios substantially greater than 1, whereas studies of aging or degenerative disease, reproduction, or reproductive disease and research involving organ or tissue transplantation typically were supported by domestically procured animals (Figure 2) and had imported:domestic ratios substantially less than 1.

Figure 2.

Responding facilities reported diverse research topics using NHP from both domestic and imported sources during 01 January 2010 through 31 December 2012. (A) The number of facilities that reported investigations of each research study type that were performed at their institution, shown according to the source of NHP used in those studies (gray, domestically sourced; black, imported). (B) The ratio of the number of facilities using imported NHP relative to the number of facilities using domestically sourced NHP for each study type. A ratio greater than 1 indicates a study type that is more dependent on imported NHP (black bars) than on domestically sourced NHP (gray bars), whereas a ratio less than 1 indicates that domestically sourced NHP typically are used.

Perceived trends in NHP use for research.

Respondents were asked about their perception of how NHP use for research purposes has changed over the past 5 y in their facility. Of the 26 respondents, 6 (23%) perceived NHP research use as having decreased, 10 (38%) perceived use as having increased, and 10 (39%) perceived use as having stayed about the same.

Finally, respondents had the opportunity to use a free-text field to record any additional comments or concerns related to NHP importation or the use of NHP in biomedical research. Three respondents provided comments, all of which expressed concerns about NHP supplies for research needs. One respondent noted that choice of species is an important discussion to have with researchers during the planning stages of projects to ensure the ability to supply the necessary research subjects and to protect human health by obtaining appropriately disease-free subjects.

Two respondents expressed concern about maintaining imported supplies of NHP. One wrote: “Although we do not import large numbers of NHP at this time, the global strategy to have this ability and flexibility with our international partners is of great value to our overall industry and it is very concerning the ever-increasing pattern of airlines unwilling to transport NHP for medical research.”

Discussion

Macaques were the most commonly reported NHP housed at responding facilities. Facilities procured cynomolgus macaques at the highest numbers over the previous 3-y period. Rhesus macaques were the species housed second most frequently and procured in the second highest numbers over the previous 3-y period. These results are comparable to findings of a 2001 retrospective literature review of NHP research, in which rhesus and cynomolgus macaques were the most common species used globally for live NHP research. In that study, North American research used rhesus macaques 3 times more frequently than cynomolgus macaques, in contrast to the current data.3 This difference may reflect the increased availability of cynomolgus macaques from breeding colonies outside of North America in the past decade. It also is noteworthy that North American research facilities imported the majority of cynomolgus and rhesus macaques used during 01 January 2010 through 31 December 2012, rather than procuring them from domestic sources. This result suggests a risk of undersupply for research needs if the availability of imported animals were to become limited in the future.

Many of the respondents reported a large proportion of terminal studies, with over half of facilities reporting greater than or equal to 80% euthanasia of NHP upon study completion and with fewer than half reporting a disposition of reassignment or retirement. Given that many research facilities reported conducting pharmaceutical studies, it is not surprising that animals are euthanized at study end, to permit safety evaluations of a range of tissues. This finding contrasts with a report that over two-thirds of individual animals were reassigned to other research projects in published studies from 2001.3 However, in the cited study,3 only 14% of papers reviewed provided information on NHP reuse, and only published studies were included in the dataset. Therefore, the prior results may differ from ours due to different reporting biases associated with a published literature review as compared with a self-administered survey. Furthermore, different respondents may have interpreted the re-use question in terms of either disposition at the end of a typical study or the ultimate disposition when an animal reaches an age or condition that would prohibit reassignment to future studies; if respondents used the latter interpretation, reports of euthanasia as a disposition might be erroneously high. Furthermore, changes in end disposition in the current study may reflect recent trends by institutional animal ethics committees to limit the numbers and types of projects in which individual NHP may be used over their lifetimes. Our finding that 3 facilities surveyed are or will be retiring some or all of their research NHP to sanctuaries after study completion is a new and emerging trend not found in previous reports.

Although the design of the current survey did not enable matching of NHP species and their origins to the different research study types, previous papers report similar trends in research project use by species.3 However, it is important to note that research funded by pharmaceutical companies may be published less often than is research funded by other sources,13 which may contribute to a ‘file drawer’ bias in systematic reviews of published literature on NHP research trends and which may make comparison across studies difficult.

Perceptions about NHP research trends varied among respondents, with an equal perception that NHP use was increasing or had plateaued, and a minority indicating a perceived decreasing trend. According to US Department of Agriculture reports, NHP use in biomedical research increased during 2000 to 2010, peaking at more than 71,000 NHP during the 2010 fiscal year.14,22 Although annual NHP use in research hovered around 71,000 animals annually during 2008 to 2010, NHP use declined substantially in 2011 and 2012 (9% and 11% decreases from 2010, respectively).22 However, because the survey asked respondents about their perceptions at a facility level and because only approximately 25% of facilities surveyed replied, sampling biases may contribute to the difference in perception compared with documented use in the United States during the same time period. Changes at an institutional level might be more stochastic and might reflect shifts in species demands, movement of scientists within or between institutions, or changes in research funding.

The current study has several limitations, most notably the potential for not being fully representative of the broader NHP research community because of a limited response rate and for response bias due to concerns over how the surveyed information might be applied. Although we obtained a diverse sample of large and small institutions that included academic, National Primate Research Center, contract, and pharmaceutical research facilities, as well as commercial breeding and importation facilities, this distribution may not fully represent the range of institutions that received the survey. At least one APV member that received the survey contacted one of the authors for clarification of the motivations for collecting these data due to concerns that the data might be used to detrimentally affect NHP importation and research. For this reason, we did not extrapolate to estimate total NHP housed and used in North America for research or describe all types of NHP research.

Finally, we were unable to ascertain which types of research studies rely on specific imported NHP species. Such a question potentially would have been quite complicated and time-consuming for respondents to complete and might have reduced the response rate further. However, we were able to use recently published studies and compare species holdings to research study types reported within each institution to support conclusions regarding which NHP species most likely are the dominant subject for the types of studies that rely most heavily on imported species.

In conclusion, an improved understanding of how imported NHP are used for biomedical research in North America will help with forecasting how changes in primate importation and availability might affect biomedical research in North America. This knowledge may inform efforts to build capacity in domestic NHP breeding programs in order to buffer against declines in the availability of imported NHP. Research institutions well recognize that NHP models should be replaced with alternatives whenever possible and that facilities should optimize the use of NHP.5,7,24 However, for some areas of research, the use of NHP remains critical for scientific progress.1,2,6,15,18,19 It will be important to ensure that sufficient supplies of these animals are available to North American researchers to continue to achieve scientific advances in these fields.10,11,16

Acknowledgments

We thank APV members for their participation in this survey and the APV Board of Directors and the Division of Global Migration and Quarantine at CDC for supporting this work. Thanks also to John Farrar for assistance with survey delivery and Nicole Cohen and Adam Langer (Division of Global Migration and Quarantine, CDC) for assistance with survey development and data analysis.

The opinions expressed in this work are those of its authors and may not represent the official positions of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the Department of Health and Human Services, or the Association of Primate Veterinarians.

References

- 1.Bontrop RE. 2001. Nonhuman primates: essential partners in biomedical research. Immunol Rev 183:5–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Capitanio JP, Emborg ME. 2008. Contributions of nonhuman primates to neuroscience research. Lancet 371:1126–1135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carlsson HE, Schapiro SJ, Farah I, Hau J. 2004. Use of primates in research: a global overview. Am J Primatol 63:225–237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cohen J. 2000. Vaccine studies stymied by shortage of animals. Science 287:959–960 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Conlee KM, Rowan AN. 2012. The case for phasing out experiments on primates. Hastings Cent Rep 42:S31–S34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Evans DT, Silvestri G. 2013. Nonhuman primate models in AIDS research. Curr Opin HIV AIDS 8:255–261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gluck JP, Bell J. 2003. Ethical issues in the use of animals in biomedical and psychopharmacological research. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 171:6–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goodman S, Check E. 2002. The great primate debate. Nature 417:684–687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hagelin J. 2004. Use of nonhuman primates in research in Sweden: 25-year longitudinal survey. ALTEX 22:13–18 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hau J, Farah IO, Carlsson HE, Hagelin J. 2000. Opponents’ statement: nonhuman primates must remain accessible for vital biomedical research, p 1593–1601. In: Balls M, van Zeller AM, Halder M. Progress in the reduction, refinement, and replacement of animal experimentation: developments in animal and veterinary sciences 31B. Oxford (UK): Elsevier [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hau J, Schapiro SJ. 2006. Nonhuman primates in biomedical research. Scand J Lab Anim Sci 33:9–12 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kaup FJ. 2002. Infectious diseases and animal models in primates. Primate Rep 62:3–59 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lexchin J, Bero LA, Djulbegovic B, Clark O. 2003. Pharmaceutical industry sponsorship and research outcome and quality: systematic review. BMJ 326:1167–1170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Miller-Spiegel C. [Internet]. 2011. Primates by the numbers: the use and importation of nonhuman primates for research and testing in the United States. [Cited 9 May 2013]. Available at: http://www.aavs.org/atf/cf/%7B8989c292-ef46-4eec-94d8-43eaa9d98b7b%7D/PRIMATES%20BY%20THE%20NUMBERS,%20AAVS.PDF

- 15.Myers DD., Jr 2012. Nonhuman primate models of thrombosis. Thromb Res 129 Suppl 2:S65–S69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.National Research Council. 2003. International perspectives: the future of nonhuman primate resources. Washington (DC): National Academies Press; [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.National Research Council, Committee on the Guidelines for the Humane Transportation of Laboratory Animals. [Internet]. 2006. Guidelines for the humane transportation of research animals. National Academies Press; [Cited 9 May 2013] Available at: http://www.nap.edu/catalog/11557.html [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Patterson JL, Carrion R., Jr 2005. Demand for nonhuman primate resources in the age of biodefense. ILAR J 46:15–22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shively CA, Clarkson TB. 2009. The unique value of primate models in translational research. Nonhuman primate models of women's health: introduction and overview. Am J Primatol 71:715–721 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Torres LB, Silva Araujo BH, Gomes de Castro PH, Romero Cabral F, Sarges Marruaz K, Silva Araujo M, Gomes da Silva S, Muniz JAPC, Cavalheiro EA. 2010. The use of New World primates for biomedical research: an overview of the last 4 decades. Am J Primatol 72:1055–1061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.United States Department of Agriculture. [Internet] 2010. Animal welfare electronic freedom-of-information requests—annual reports. Annual report of research facility (APHIS Form 7023) for 2010. 27 July 2011. [Cited 9 May 2013]. Available at: http://www.aphis.usda.gov/animal_welfare/efoia/7023.shtml

- 22.United States Department of Agriculture. [Internet] 2013. Animal care and information search tool. [Cited 9 May 2013] Available at: http://acissearch.aphis.usda.gov/LPASearch/faces/CustomerSearch.jspx

- 23.Wadman M. 2012. Activists ground primate flights. Nature 483:381–382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weatherall D, Munn H. 2007. Moving the primate debate forward. Science 316:173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]