Abstract

Most commercial Glycine max (soybean) varieties have yellow seeds because of loss of pigmentation in the seed coat. It has been suggested that inhibition of seed coat pigmentation in yellow G. max may be controlled by homology-dependent silencing of chalcone synthase (CHS) genes. Our analysis of CHS mRNA and short-interfering RNAs provide clear evidence that the inhibition of seed coat pigmentation in yellow G. max results from posttranscriptional rather than transcriptional silencing of the CHS genes. Furthermore, we show that mottling symptoms present on the seed coat of G. max plants infected with some viruses can be caused by suppression of CHS posttranscriptional gene silencing (PTGS) by a viral silencing suppressor protein. These results demonstrate that naturally occurring PTGS plays a key role in expression of a distinctive phenotype in plants and present a simple clear example of the elucidation of the molecular mechanism for viral symptom induction.

INTRODUCTION

In Glycine max (soybean), at least three independent genetic loci (I, R, and T) control pigmentation of the seed coat (Bernard and Weiss, 1973). The seed coat color is controlled by allelic combinations of R and T, which determine the pigments, the anthocyanin and proanthocyanidin products (Todd and Vodkin, 1993; Zabala and Vodkin, 2003). By contrast, the I locus controls the spatial distribution and accumulation of anthocyanin and proanthocyanidin pigments in the seed coat. The I locus has four alleles; one of which, the i allele, results in complete pigmentation of the seed coat, whereas the remaining three alleles (I, ii, and ik) inhibit anthocyanin and proanthocyanidin production in a specific manner as follows: the I allele inhibits pigmentation over the entire seed coat resulting in a uniform yellow color on mature harvested seeds, and ii and ik alleles inhibit pigmentation except for the hilum and the saddle-shaped region surrounding the hilum, respectively. The dominant relationships between the four alleles are I > ii > ik > i.

It has been shown that the steady state level of CHS mRNA is specifically reduced in seed coats with the I allele, whereas it is not reduced in the pigmented seed coats of G. max carrying the i allele (Wang et al., 1994). Consequently, CHS activity in nonpigmented seed coats with the I allele was significantly lower than that in the pigmented seed coats with the i allele. Because CHS is a key enzyme of the branch of the phenylpropanoid pathway leading to the biosynthesis of anthocyanin and proanthocyanidin pigments, reduction of CHS mRNA by the I allele is likely to be the basis for the inhibition of seed coat pigmentation (Wang et al., 1994). In G. max, CHS is encoded by a multigene family composed of at least seven members, CHS1 to CHS7 (Akada et al., 1993; Akada and Dube, 1995). Previous analysis of the I allele showed it to be a region of duplicated CHS genes (Todd and Vodkin, 1996; Senda et al., 2002a, 2002b). Sequence analysis of part of the I allele revealed that a truncated form of another CHS gene, ΔCHS3, is located in the inverse orientation immediately upstream of ICHS1 (one of the CHS1 genes), creating an inverted repeat of the CHS sequence (Senda et al., 2002a). It was proposed that the reduction in accumulation of CHS mRNA caused by the I allele may be because of homology-dependent gene silencing caused by base-pairing of the CHS genes, although whether the I allele acts transcriptionally or posttranscriptionally was not determined (Todd and Vodkin, 1996; Senda et al., 2002a, 2002b).

In addition to genetic effects caused by the I allele, G. max seed coat pigmentation also can be affected after infection by certain viruses (Bernard and Weiss, 1973). In yellow G. max infected with the potyvirus Soybean mosaic virus (SMV) or with the G. max strain of Cucumber mosaic virus (CMV-Sj), pigments appear on seed coats in irregular streaks and patches, referred to as mottling. Both SMV and CMV-Sj are seed transmissible with high frequency (>50%) and thus reach seed coat. The color appearance of mottling depends on whether the G. max variety has the other genetic loci, including T and R. Plants possess an antiviral defense mechanism that targets viral RNAs for degradation in a sequence-specific manner (Vance and Vaucheret, 2001; Voinnet, 2001; Waterhouse et al., 2001). Expression of plant transgenes also can be affected by this defense mechanism, whereby transgene mRNA, and in some cases homologous endogene mRNA, is destroyed posttranscription (Vaucheret et al., 1998). This phenomenon is called posttranscriptional gene silencing (PTGS). Similar mechanisms have been found in fungi (Cogoni and Macino, 1999) and animals (Fire et al., 1998; Kennerdell and Carthew, 1998), and collectively these phenomena are referred to as RNA silencing. A key part of the silencing process is the production of small (21 to 26 nucleotide) double-stranded RNAs that are homologous in sequence to the viral RNA or mRNA that is to be silenced (Hamilton and Baulcombe, 1999; Hamilton et al., 2002; Llave et al., 2002). These short-interfering RNAs (siRNAs) provide the sequence specificity for the degradation of target RNAs and are diagnostic of PTGS. Many plant viruses, including SMV and CMV, produce proteins that suppress RNA silencing to overcome the antiviral defense mechanism of the host and facilitate virus infection (Llave et al., 2000; Voinnet et al., 2000; Li and Ding, 2001; Mallory et al., 2001; Guo and Ding, 2002; Qu et al., 2003). These virus-encoded suppressor proteins also are able to interfere with PTGS of host and transgene mRNAs (Kasschau and Carrington, 1998).

In this article, we investigated changes in pigment production in G. max seed coats and demonstrate that inhibition of pigmentation induced by the I allele results from PTGS of CHS genes. Conversely, stimulation of pigmentation induced by virus infection results from suppression of PTGS of CHS genes, providing an explanation of the molecular mechanism for viral symptom induction.

RESULTS

Inhibition of Seed Coat Pigmentation in Yellow G. max Is Attributable to Natural PTGS of CHS Genes

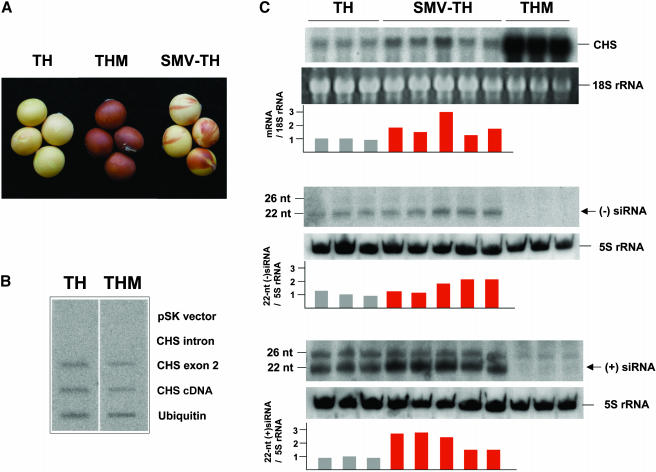

The G. max cultivar Toyohomare (TH) has yellow seeds determined by a dominant allele of the I locus (I genotype), whereas a spontaneous mutant line at the I locus (THM) (i genotype) has pigmented seeds (Figure 1A). Our sequence analysis revealed that some part of the corresponding I allele has been deleted in THM (M. Senda, unpublished data). Previously, it was suggested that either transcriptional or posttranscriptional silencing of CHS genes may be involved in the inhibition of seed coat pigmentation (Todd and Vodkin, 1996; Senda et al., 2002a, 2002b). We conducted nuclear run-on transcription assays to examine whether CHS transcripts initially accumulate in the nucleus. Briefly, we created twin membranes in which the CHS intron, exon, and cDNA were blotted. Nuclear run-on transcription was performed using the nuclei prepared from either TH or THM. One of the twin membranes was hybridized with labeled RNAs of TH, whereas the other was with those of THM. The results of this assay showed that the levels of CHS pre-mRNA were comparable in extracts of nuclei from both TH and THM seed coats (Figure 1B). Failure to detect the CHS intron was perhaps because of the AT-rich nature of this sequence and the lack of hybridization of the labeled probe to this region during the high-stringency conditions of the assay (Kanazawa et al., 2000). These data suggest that CHS transcription is not reduced by the I allele (TH line); hence, inhibition of CHS expression is posttranscriptional.

Figure 1.

Seed Pigmentation in G. max.

(A) Seed colors of the G. max cultivar TH, its spontaneous mutant (THM), and SMV-infected TH (SMV-TH).

(B) Nuclear run-on transcription assay of the seed coat tissues from TH and THM. Hybridizations were performed with labeled run-on transcripts that detect CHS. The filters contained immobilized DNAs of the cloning vector pSK, CHS intron, CHS exon 2, CHS cDNA, and ubiquitin.

(C) RNA gel blot analysis of CHS mRNA and siRNAs from the three samples of G. max. Total RNAs were isolated from the seed coat of three independent plants of TH and THM and five of SMV-infected TH. SMV RNA was detected specifically in all SMV-infected THs by RT-PCR for the CP gene and RNA gel blot analysis (data not shown). RNA gel blots were hybridized with a CHS-specific probe (first panel). CHS siRNAs were detected by hybridization either with labeled sense (fourth panel) or antisense (seventh panel) CHS-specific RNA probes. The 18S rRNA (second panel) or 5S rRNA (fifth and eighth panels) was shown as an internal control for equal loading of RNA samples. The relative level of CHS mRNA was calculated by dividing the CHS-specific radioactivity by the 18S rRNA level (third panel). The relative level of the 22-nucleotide siRNA was calculated by dividing the siRNA counts by 5S rRNA-specific radioactivity (sixth and ninth panels). The positions for 22- and 26-nucleotide DNA oligomers are shown at the left. nt, nucleotide.

We then analyzed the levels of CHS mRNA and CHS-specific siRNAs to verify that the inhibition of seed coat pigmentation by the I allele is because of natural PTGS of CHS genes in yellow G. max. In THM tissue (pigmented seed coat), the level of CHS mRNA was increased ∼80-fold relative to that in TH tissue (nonpigmented seed coat) (Figure 1C, first panel). Next, the small RNA fraction was isolated from seed coat to detect 21- to 26-nucleotide siRNAs, which are associated with PTGS. As shown in Figure 1C, CHS-specific siRNAs were clearly detected in TH tissue with both sense and antisense probes. By contrast, the siRNAs were not detected (sense probe) or barely detected (antisense probe) in the seed coat of the THM line. These results are consistent with inhibition of seed coat pigmentation by the I allele and thus represents an example of naturally occurring PTGS of the CHS endogene family.

Infection with a Potyvirus Partially Reverses PTGS of CHS Genes by the I Allele

TH is susceptible to infection by SMV, which is an RNA virus belonging to the potyvirus genus. Potyviruses encode the helper component–proteinase (HC-Pro) protein, which is a potent suppressor of gene silencing (Llave et al., 2000; Mallory et al., 2001, 2002). Infection of G. max by SMV often causes mottled seeds with pigmented streaks or patches (Figure 1A). We actually detected SMV in the seed coat by RT-PCR for the coat protein gene and RNA gel blot analysis (data not shown). In TH seed coat with sporadic pigmentation from plants infected with SMV, the level of CHS mRNA was increased approximately twofold when compared with uninfected TH tissue (Figure 1C, first panel), indicating interference by the virus with silencing of the CHS genes in parts of the seed coat. In the SMV-infected tissue, siRNAs were detected at a significant level, also at an approximately twofold higher level than that seen in uninfected TH tissue (Figure 1C).

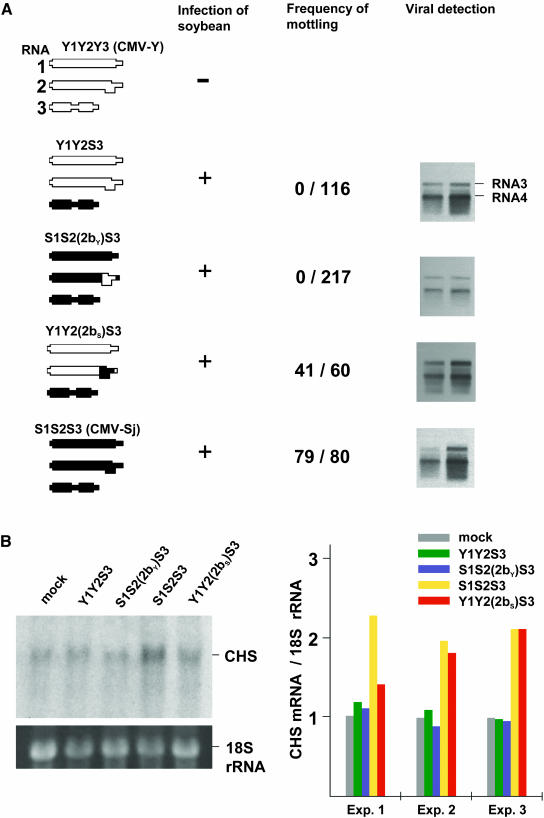

CMV 2b Suppressor Proteins from Different Strains Differentially Influence Seed Coat Mottling

G. max seed mottling also can be caused by CMV, a virus that is unrelated to SMV and encodes an alternative silencing suppressor protein, the 2b protein, which inhibits PTGS by a different mechanism to that of SMV HC-Pro (Mlotshwa et al., 2002). CMV has three genomic RNAs: RNA1 encodes the 1a protein (methyltransferase/RNA helicase), RNA2 encodes the 2a protein (replicase) and the 2b protein, and RNA3 encodes a virus movement protein and the coat protein (CP). The 2b protein is translated from a subgenomic RNA, RNA4A, which is generated from RNA2. A subgenomic RNA, RNA4 is synthesized from RNA3 as the mRNA for CP. Viable pseudorecombinant CMV strains can be created by mixing the three viral RNAs from different virus isolates, making it possible to attribute particular infection phenotypes to specific CMV RNAs (and their encoded proteins). For further analysis of seed mottling, we used CMV rather than SMV because we were able to construct infectious clones of two CMV isolates with different properties, facilitating the production and analysis of pseudorecombinant strains. Different cultivars have specific susceptibilities to particular plant viruses. For these experiments, we used the yellow G. max cultivar Shiromame (SM) with the I genotype because TH was not susceptible to CMV. CMV isolate Y (CMV-Y) does not infect the SM, whereas CMV-Sj does infect this cultivar, inducing a high frequency of mottling in the seeds compared with the other available cultivars. The three genomic RNAs of CMV-Y and CMV-Sj were designated Y1 to Y3 and S1 to S3, respectively. By mixing these RNAs in different combinations, it was found that RNA3 of CMV-Sj was required for the virus to infect G. max and that RNA1 and RNA2, which encode the 2b silencing suppressor protein, were not involved in the strain specificity of G. max infection (Figure 2A).

Figure 2.

Effect of Viral Infection on Seed Coat Mottling.

(A) Schematic representation of CMVs used for G. max inoculation is shown in the left column. CMV contains a tripartite positive-sense RNA genome (RNA1 to RNA3). RNA2 encodes the 2b protein in the 3′ half. RNA4 is a subgenomic RNA synthesized from the 3′ end region of RNA3 and serves as the mRNA for CP. The regions of noncoding sequences are narrowed. Five individual SM plants were inoculated with each of four CMVs. Frequency of mottling (number of mottled seeds/number of total seeds counted) was scored (third column). Viral accumulation in the seed coat was confirmed by RNA gel blot analysis (right column). RNAs were extracted from the immature seed coat tissues, which had been collected from 10 seeds randomly harvested from the same independent plant (2 to 3 seeds per pod). To determine viral concentrations, two independent plants were used for duplication. We cannot discriminate pigmented and nonpigmented seeds at the immature stage. RNA gel blots were hybridized with a probe specific to the 3′ noncoding region (340 nucleotides) of CMV RNA3 (RNA4), which shares ∼70 and 75% sequence identity with the corresponding regions of RNA1 and RNA2, respectively.

(B) RNA gel blot analysis of CHS mRNA in G. max (SM) seed coats. Total RNAs were extracted from G. max plants inoculated with water (mock), Y1Y2S3, S1S2(2bY)S3, CMV-Sj (S1S2S3), or Y1Y2(2bS)S3. Equal amounts of total RNAs were separated by electrophoresis, blotted onto membrane, and hybridized with a CHS-specific probe (left panel). Ethidium bromide–stained 18S rRNA is shown as a loading control. The relative level of CHS mRNA was calculated for each experiment as in Figure 1; the levels of mock were set at 1.0 (right panel).

However, although a pseudorecombinant containing RNA1 and RNA2 of CMV-Y together with RNA3 of CMV-Sj (Y1Y2S3) was able to infect G. max, it did not cause mottling of the seed coat (Figure 2A). These results indicated that sequences on RNA1 or RNA2 were responsible for G. max seed coat mottling and raised the possibility that, as with SMV, the silencing suppressor protein of CMV might be the determinant of mottling. Two additional pseudorecombinant viruses were constructed containing a hybrid molecule in which the majority of RNA2 was from one isolate, whereas the 2b gene was from the second isolate. The Y1Y2(2bS)S3 pseudorecombinant has CMV-Y RNA2 with the CMV-Sj 2b gene, and the S1S2(2bY)S3 pseudorecombinant has CMV-Sj RNA2 with the CMV-Y 2b gene. In plants infected with CMV Y1Y2(2bS)S3, 41 of 60 seeds were mottled, whereas in plants infected with CMV S1S2(2bY)S3, none of 217 seeds were mottled (Figure 2A). Thus, the 2b gene of CMV-Sj but not the 2b gene of CMV-Y is the determinant of seed mottling in G. max.

RNA gel blot analysis showed that there were abundant viral RNAs in the seed coat of plants infected with all of the pseudorecombinants, but no correlation between mottling and viral concentration was found (Figure 2A). For example, in spite of a higher concentration of virus in the Y1Y2S3-infected tissues, there was no mottling on the seeds. To determine CHS mRNA levels in the virus-infected seed coat, further RNA gel blot analyses were conducted. As was anticipated, the CHS mRNA level in the CMV-Sj–infected (S1S2S3) seed coat was significantly increased compared with that in the CMV S1S2(2bY)S3-infected seed coat and uninfected G. max plants (Figure 2B). In addition, plants infected with pseudorecombinants Y1Y2S3 and S1S2(2bY)S3 had low levels of CHS mRNA, whereas the pseudorecombinant carrying the Sj strain 2b gene [Y1Y2(2bS)S3] induced increased levels of CHS mRNA. These observations are consistent with the results obtained from experiments performed with SMV and provide further evidence that the CMV 2b silencing suppressor protein from strain Sj reverses PTGS of the CHS mRNA in G. max.

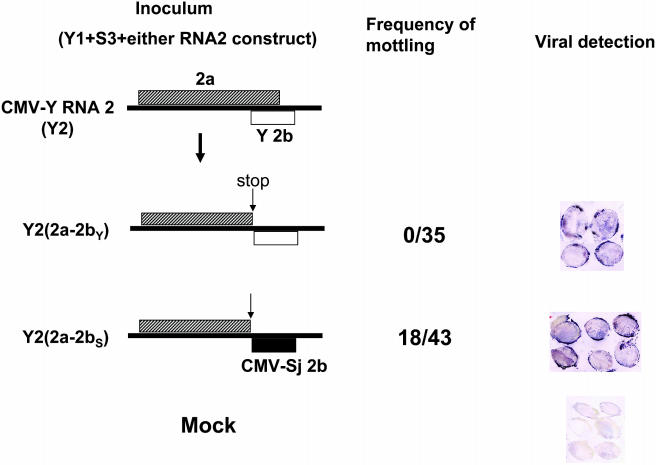

About two-thirds of the 2b gene overlaps the 2a (replicase protein) gene but in a different reading frame. Thus, by exchanging the 2b gene between different isolates, we also had to exchange the C-terminal part of the 2a gene between these isolates. To directly prove that the 2b gene of CMV-Sj is really responsible for seed mottling, we inserted a stop codon just upstream of the 2b gene in CMV-Y RNA2 [Y2(2a-2bY)] (Figure 3) because previous studies reported that the C-terminal part of the 2a protein is dispensable for viral infection (Ding et al., 1995; Shi et al., 2003). Then, the 2b gene in Y2(2a-2bY) was replaced by the 2b gene of CMV-Sj, creating Y2(2a-2bS) (Figure 3). Both constructs could systemically infect SM when coinoculated with Y1 and S3. As shown in Figure 3, though both viruses reached the seed coat, Y2(2a-2bS) induced seed mottling but Y2(2a-2bY) did not, suggesting that the 2b gene of CMV-Sj controls seed mottling.

Figure 3.

Effect of the 2b Protein on Seed Coat Mottling.

The 2b gene (2bY) was located just downstream of the 2a gene in the RNA2 background of CMV-Y by inserting a stop codon before the 2b gene to create an RNA2 construct of Y2(2a-2bY). The 2b gene was replaced by that of CMV-Sj to create Y2(2a-2bS). Each RNA2 construct was inoculated onto SM together with Y1 + S3. Frequency of mottling (number of mottled seeds/number of total seeds counted) was scored. Viral accumulation in seed coat was confirmed by tissue prints.

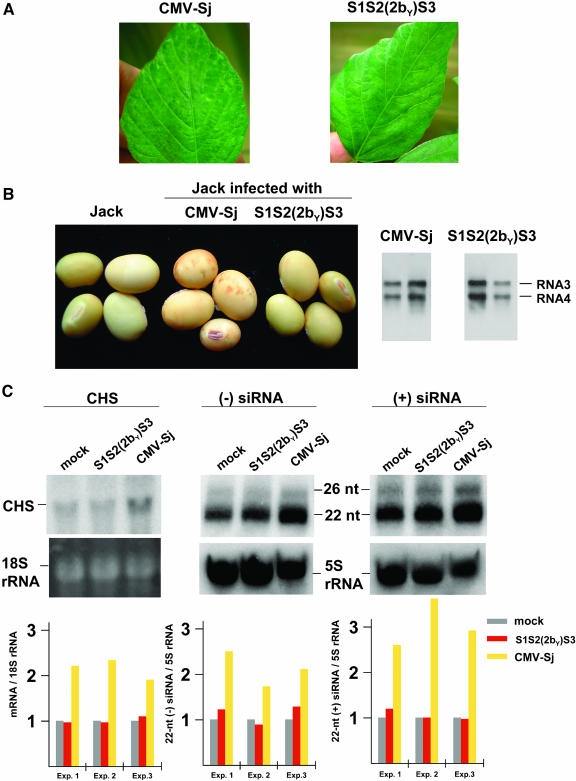

CMV 2b Suppressor Proteins from Different Strains Differentially Influence CHS siRNA Levels

Although using the method of Wang and Vodkin (1994) mRNAs could be extracted from the mottled SM seed coat, the yield was always low because of the production of procyanidins in the black mottling. In addition, it was difficult to extract high-quality siRNAs. We thus used the yellow G. max cultivar Jack (I genotype) in which RNA extraction is more efficient to analyze the nature of CHS-specific siRNAs in the CMV-infected seed coat because of lack of procyanidins. In addition, Jack could be used for the further analysis by Agrobacterium tumefaciens–mediated gene silencing of a transgene as described below. The Jack plants infected with CMV-Sj and S1S2(2bY)S3 showed similar leaf symptoms (mild mosaic) (Figure 4A). On the other hand, as was observed for the SM, the CMV-Sj–infected Jack plants showed pigmented patches on the seed coat, but S1S2(2bY)S3 did not induce any mottling (Figure 4B); both viruses were detected in the seed coat (Figure 4B, right panel). The level of CHS mRNA in CMV-Sj–infected tissue was more than approximately twofold higher than that of CMV S1S2(2bY)S3-infected tissue (Figure 4C). In three independent experiments, the level of accumulation of CHS-specific siRNAs in tissue infected with CMV S1S2(2bY)S3 was almost equivalent to that detected in noninfected Jack plants. However, the level of siRNAs in tissue infected with CMV-Sj was at least 1.8-fold higher than that in S1S2(2bY)S3-infected tissue (Figure 4C). A similar small increase in the level of CHS-specific siRNAs also was observed in the seed coat of yellow G. max infected with SMV (Figure 1C).

Figure 4.

Effect of the 2b Sequence on the Levels of CHS mRNA and siRNAs in G. max.

(A) Leaf symptoms of the Jack infected either with CMV-Sj or S1S2(2bY)S3.

(B) Seed coat mottling of the Jack infected either with CMV-Sj or S1S2(2bY)S3. CMV-Sj induced the mottling symptoms on the seeds. On the other hand, S1S2(2bY)S3 did not induce such mottling symptoms, but ∼10% of the seeds showed some pigmentation just on the hilum. The color of mottling on the Jack seeds was weaker than that observed on the TH seeds (Figure 1A). This is perhaps because of the variation in the genetic background among the G. max cultivars; other than I, some other genes are often involved in the seed color alteration. RNA gel blot analysis of viral RNAs was performed as described in Figure 2.

(C) RNA gel blot analysis of CHS mRNA and siRNAs from uninfected Jack plants (mock) and Jack plants infected either with S1S2(2bY)S3 or CMV-Sj. RNA gel blots were hybridized with a CHS-specific probe (top left panel). CHS siRNAs were detected by hybridization with either labeled sense (top center panel) or antisense (top right panel) CHS-specific RNA probes. The positions for 22- and 26-nucleotide DNA oligomers are indicated. The relative levels of CHS mRNA and the 22-nucleotide siRNA were calculated for each experiment as described in Figure 1; the levels of mock were set at 1.0 (bottom panels). nt, nucleotide.

A. tumefaciens–Mediated Systemic Gene Silencing of a Transgene Is Similar to Natural PTGS in G. max

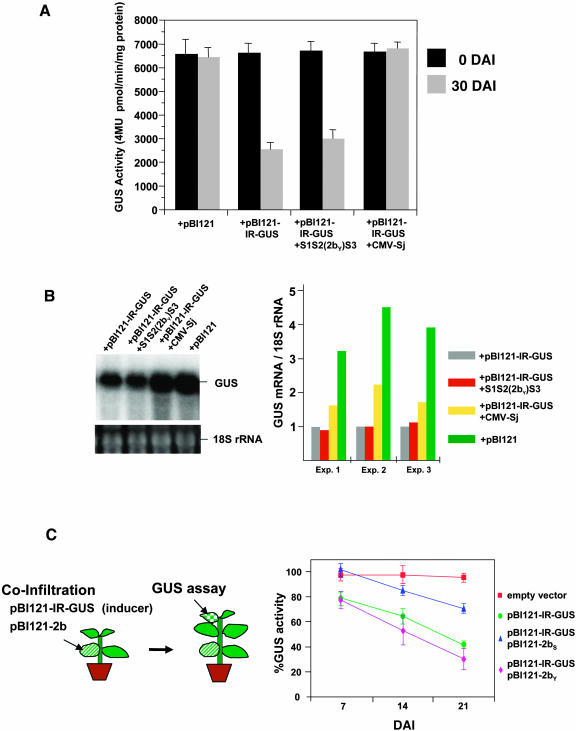

To determine if we could reproduce the nature of CHS gene silencing in G. max with respect to viral infection by artificially induced silencing, we developed a system for A. tumefaciens–mediated (systemic) gene silencing of a transgene in G. max. These experiments made use of a transgenic line of G. max cultivar Jack expressing the ß-glucuronidase (GUS) gene (Jack-GUS) (Santarém and Finer, 1999). After transient expression of pBI121-IR-GUS (silencing inducer) by agro-infiltration into an expanded leaf of the Jack-GUS plant, a systemic silencing-induced decline of the GUS transgene activity in upper leaves started at 7 to 10 d after infiltration (DAI). At 30 DAI, GUS activity in the infiltrated plants decreased to about one-third of that in control plants treated with A. tumefaciens containing an empty vector, the GUS gene–deleted pBI121 (Figure 5A). Agro-infiltration with pBI121-IR-GUS into Jack-GUS infected with the pseudorecombinant CMV isolate S1S2(2bY)S3 resulted in a reduction of GUS transgene activity to a level similar to that obtained after agro-infiltration with pBI121-IR-GUS into the noninfected Jack-GUS (Figure 5A). However, the GUS activity was maintained in GUS-infiltrated plants after infection with CMV-Sj, remaining similar to that observed in the control plants (Figure 5A). These results indicate that PTGS of the GUS transgene was successfully induced by agro-infiltration with pBI121-IR-GUS and that GUS silencing was prevented by infection with CMV-Sj but not with CMV S1S2(2bY)S3.

Figure 5.

A. tumefaciens–Mediated Systemic Gene Silencing in the Transgenic G. max Infected with CMV-Sj and S1S2(2bY)S3 and Effect of CMV 2b on Systemic RNA Silencing.

(A) The GUS activity (4 MU pmol/min/mg protein) in upper leaves was measured 30 d after agro-infiltration. The Jack-GUS plants were inoculated with virus 7 d before agro-infiltration. Viral infection was confirmed by ELISA and RNA gel blot analysis. Results represent the mean values with standard deviations as error bars from four to five plants. +pBI121 represents infiltration with pBI121 lacking the GUS gene (empty vector). +pBI121-IR-GUS is infiltration with pBI121 containing the inverted repeat (IR) construct of the GUS gene. 4MU, 4-methyl-umbelliterone.

(B) RNA gel blot analysis of GUS mRNA in Jack-GUS. Total RNAs were extracted from the leaves of Jack-GUS (+pBI121), GUS-silenced Jack-GUS (+pBI121-IR-GUS), and GUS-silenced Jack-GUS inoculated either with S1S2(2bY)S3 [+pBI121-IR-GUS + S1S2(2bY)S3] or with CMV-Sj (+pBI121-IR-GUS +CMV-Sj). RNA gel blots were hybridized with a GUS-specific probe. The relative level of GUS mRNA was calculated by dividing the GUS-specific radioactivity by the 18S rRNA level; the levels of GUS-silenced Jack-GUS (+pBI121-IR-GUS) were set at 1.0 (right panel).

(C) The effects of the 2b gene on systemic RNA silencing. Jack-GUS plants were infiltrated with A. tumefaciens containing pBI121-IR-GUS together with another culture containing a 35S-2b binary construct, pBI121-2b (left panel). GUS activity in the upper leaves was monitored for systemic silencing at 7, 14, and 21 DAI. For each experiment, four independent plants were tested, and the results represent the mean values with standard deviations as error bars.

The levels of GUS-specific mRNA in the upper leaves of the infiltrated and virus-infected Jack-GUS plants were examined by RNA gel blot analysis. Silenced GUS-infiltrated plants contained approximately fourfold less GUS mRNA than did control plants infiltrated with the empty vector (Figure 5B). To confirm that the decrease in GUS mRNA was a result of silencing of the GUS gene, we looked for the presence of siRNAs using a transcribed GUS RNA probe. The GUS siRNAs were detected in the silenced plants (data not shown). Infection of GUS-infiltrated plants with CMV S1S2(2bY)S3 did not lead to accumulation of GUS mRNA above that seen in silenced plants. Infection of GUS-infiltrated plants with CMV-Sj increased the level of GUS mRNA to that seen in control plants. These results mirror those from the experiments on the suppression of CHS PTGS in yellow G. max seed coats, in that CMV-Sj was able to suppress silencing in G. max, whereas CMV S1S2(2bY)S3, carrying the 2b gene of CMV-Y, was not able to suppress PTGS in G. max.

To investigate the direct effects of the 2b protein on systemic RNA silencing, pBI121-IR-GUS (silencing inducer) was agro-infiltrated into the leaves of Jack-GUS plants together with pBI121-2b. In the upper leaves, the relative GUS activity decreased more slowly in the 2bS-infiltrated plants than in the 2bY-infiltrated plants (Figure 5C). The results suggest that 2bS partially suppressed systemic silencing signal(s) in the infiltrated leaves but 2bY did not.

DISCUSSION

Natural PTGS of CHS Genes

In this article, we present several lines of evidence suggesting that in yellow G. max with the I genotype, seed coat pigmentation is inhibited by PTGS of CHS genes. First, nuclear run-on experiments show that in yellow G. max, transcription of CHS genes is not reduced in the seed coats; thus, the decrease in CHS mRNA occurs at the posttranscriptional level. Second, the CHS-specific siRNAs, which are associated with PTGS, are detected only in the seed coats of yellow G. max (I genotype) but not in those of pigmented G. max with a spontaneous mutation at the I locus (i genotype). Third, infection of I/I plants with viruses such as SMV and CMV-Sj induces accumulation of CHS mRNA, resulting in the appearance of pigmented patches on the nonpigmented seed coat (mottling). Fourth, the incidence of seed coat mottling by CMV infection depends on the 2b (the viral silencing suppressor) sequence, indicating that the 2b protein interferes with the PTGS of CHS genes.

Recently, Kusaba et al. (2003) analyzed a rice (Oryza sativa) mutant (LGC-1) that had been created by γ radiation and has low glutelin content. They demonstrated that in LGC-1, the mutagenesis procedure resulted in the creation of a glutelin gene inverted repeat structure that induced RNA silencing of the glutelin multigene family. Previous studies of flower color in Petunia suggested that variation in pigment patterning could be caused by PTGS of CHS genes (Metzlaff et al., 1997; Teycheney and Tepfer, 2001). In one of the studies, flower color was shown to be affected by CMV infection (Teycheney and Tepfer, 2001). However, our analysis of CHS-specific siRNAs demonstrates conclusively the involvement of naturally occurring PTGS in the inhibition of G. max seed coat pigmentation, and we show unequivocally that seed coat pigmentation can be affected by expression of a virus-encoded silencing suppressor protein.

Effect of Viral Infection on Accumulation of CHS-Specific siRNAs

Although in this study infection of G. max with SMV and CMV-Sj suppressed PTGS of CHS genes and led to an increase in CHS mRNA accumulation, in neither case did the suppression prevent accumulation of CHS-specific siRNAs. In fact, siRNA levels in the virus-infected plants increased approximately twofold. Many previous studies reported that the formation of siRNAs was suppressed in the presence of viral suppressors (Mallory et al., 2001; Hamilton et al., 2002); however, this may reflect the particular silencing assay that was employed and may depend specifically on the nature of the silencing trigger. Indeed, in one report, Johansen and Carrington (2001) showed that HC-Pro suppressed the silencing of green fluorescent protein transgene mRNA but did not prevent siRNA formation and that the level of the siRNAs was even greater than that of the green fluorescent protein–silenced control plant in the absence of P1/HC-Pro. They proposed that the suppressor activity of HC-Pro can, in part, be overcome and that RNA silencing can occur even with the accumulation of siRNAs if the double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) silencing inducer accumulates to a high enough level. Similarly, Guo and Ding (2002) have reported an accumulation of GUS-specific siRNAs in Nicotiana tabacum (tobacco) plants produced by crossing a GUS-silenced plant and a plant expressing the 2b protein of CMV, indicating that there are situations in which the CMV 2b protein suppresses silencing without completely preventing siRNA accumulation. Our observations of an increase in accumulation of siRNAs after suppression of gene silencing by viral infection are in agreement with these previous reports.

Completion of the sequencing of the I allele (M. Senda, unpublished data) shows that it has a more complex structure than was previously thought. The I allele contains two consecutive inverted repeats of the ΔCHS3 and ICHS1 genes that are immediately downstream of a DnaJ promoter-like sequence. Transcription of the I allele perhaps produces dsRNA, which would act as a constant source of siRNAs that can mediate silencing of the active CHS gene family. However, we showed that I/I plants still express substantial amounts of CHS mRNA in the CHS-silenced (nonpigmented seed coat) tissues even in the absence of virus infection, indicating that I allele–derived siRNAs do not induce complete CHS gene silencing. It is probable that a certain threshold of CHS activity is required to make the seeds pigmented and that below this threshold, even though CHS mRNA is present, the seeds are unpigmented. Virus-encoded suppressor activity will increase the level of CHS mRNA in the infected seed coat, which then starts to synthesize pigments. This elevated CHS mRNA will then act as a template for the further generation of siRNAs, which when combined with the siRNAs derived from the I allele dsRNA, accumulate to increased levels.

Differential Activities of 2b Proteins from Different CMV Isolates

CMV encoding the 2b gene from isolate Sj can suppress silencing of both a naturally occurring (CHS) gene and a transgene (GUS) in G. max, whereas the same virus but encoding the 2b gene from CMV-Y is not. The 2b proteins from CMV-Y and CMV-Sj share 67% amino acid sequence identity. CMV-Sj is adapted specifically to wild and cultivated G. max (Hong et al., 2003) and has never been isolated in the field from other plant species. Considering that the CMV-Y 2b protein has never acted in the PTGS process of G. max, it may not interact with a G. max factor necessary for its suppressor activity.

Besides the suppressor activity, the CMV 2b protein plays some other roles in viral infection. The CMV 2b protein was identified originally as a determinant of virus pathogenicity with influence on cell-to-cell and systemic movement of the virus (Shi et al., 2003). It also will be interesting to examine whether, as well as facilitating suppression of CHS PTGS in G. max, the CMV-Sj 2b protein influences other aspects of infection, such as extent of virus movement or virus persistence.

METHODS

Plant and Virus Materials

All G. max cultivars and lines used were homozygous at the I, R, and T loci; thus, only one allele is indicated in this article. TH (Irt) and its spontaneous mutant line (irt) (THM) were provided by the Tokachi Agricultural Experimental Station. TH is one of the most popular cultivars in Hokkaido, Japan. THM was isolated in the same agricultural experimental station in 1998. After the analysis of the I locus in THM, we found that it has some sequence deletion in the ICHS1 region (M. Senda, unpublished data). In this respect, THM is similar to the other known mutants whose genotype was changed from I to i (Todd and Vodkin, 1996; Senda et al., 2002a, 2002b). Japanese yellow G. max cultivar SM (IRT) was provided by the Hokkaido Genetic Resource Center, Japan. SM shows black mottling containing procyanidins because of RT genotype. Jack (Irt) and a transgenic Jack line expressing GUS (Jack-GUS) was a kind gift of John J. Finer (Ohio University). The SMV used for this study was isolated from experimental fields in Aomori prefecture, Japan. CMV-Sj and CMV-Y have been maintained in Hokkaido University, Japan.

Nuclear Run-On Transcription Assay

The isolation of nuclei from seed coats and the nuclear run-on transcription assays were performed essentially as described by Kanazawa et al. (2000). We conducted some preliminary tests to determine an appropriate stage of seed development for the nuclear run-on transcription assay. Comparative RNA gel blot analysis between TH and THM seed coats revealed that CHS gene silencing in TH has already occurred in the seed of <50 mg fresh weight and was maintained throughout the seed development (M. Senda, unpublished data). Therefore, seed coats were peeled and collected from immature seeds of <50 mg fresh weight. The three different regions (intron, exon 2, and cDNA) of G. max CHS7 (GmCHS7, DDBJ/GenBank/EMBL accession number M98871, Akada et al., 1993) were amplified by PCR or RT-PCR, and each product was then cloned into pBluescript II SK+ (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA). A clone containing the G. max ubiquitin gene (Subi-1, accession number D16248) also was used as a positive control. Samples of 1 μg of these plasmid DNAs were applied to a Zeta-Probe blotting membrane using a slot blot apparatus according to the manufacturer's specifications (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA).

Total RNA Extraction and RNA Gel Blot Analysis

Seed coat RNAs were extracted essentially according to the protocols of Wang and Vodkin (1994) and prepared from the seeds of 300 to 400 mg fresh weight, from which a sufficient amount of seed coat was obtained. The standard phenol/chloroform method was used with all G. max except CMV-infected SM. Because the seed coats from CMV-infected SM contain procyanidins in the black mottling, a modified method, including treatment with BSA and polyvinylpolypyrrolidone for the procyanidin-containing tissues, was adopted to detect CHS mRNA (Figure 2B) (Wang and Vodkin, 1994). RNA gel blot analysis, including the preparation of the G. max CHS probe, was performed as described previously (Senda et al., 2002b).

Extraction of Small RNAs and Detection of siRNAs

The initial steps for small RNA extraction were the same as those described above for total RNA extraction. After the lithium chloride precipitation of high molecular weight RNA, the supernatant was transferred to a new tube, and small RNAs and genomic DNA were precipitated with ethanol. The pellet was dissolved in water, genomic DNA was removed by precipitation with one-third volume of 20% PEG8000/2 M NaCl, and small RNAs in the resulting supernatant were ethanol precipitated. Small RNAs were then recovered and redissolved in water. Aliquots of 20 μg of small RNAs were precipitated with 3 volumes of 100% ethanol and stored at −70°C. Small RNAs and DNA oligomers were separated in a 15% polyacrylamide gel containing 7 M urea and then blotted to Hybond-NX membrane (Amersham Biosciences, Buckinghamshire, UK). The sequences of the DNA oligomers designed from the GmCHS7 sequence were as follows: 26-nucleotide sense (5′-GAAGATGAAGGCCACTAGAGATGTGC-3′), 22-nucleotide sense (5′-GGACCTGGACTTACCATTGAAA-3′), 26-nucleotide antisense (5′-TTCCAATGGCAAGGATGGTTGCTGGG-3′), and 22-nucleotide antisense (5′-GTCATGTGGTCACTGTTGGTGA-3′). Detection of siRNAs was performed essentially as described by Dalmay et al. (2000). Sense- and antisense-specific riboprobes corresponding to GmCHS7 sequence were synthesized using an in vitro transcription system (Promega, Madison, WI). The membranes were reprobed with the G. max 5S rDNA (accession number X15199) as a control for equal gel loading.

Quantification of the Band Intensities

The hybridization signals were visualized and the band intensity was quantified using a Bio-Imaging Analyzer BAS 1000 (Fuji Photo Film, Tokyo, Japan). The band intensity of ethidium bromide–stained 18S rRNA as a loading control was densitometrically quantified with image analysis software (NIH Image version 1.63 program). The relative amount of the CHS (or GUS) mRNA was calculated by dividing the CHS (GUS)-specific radioactivity by the 18S rRNA. The relative levels of siRNAs were calculated by dividing the siRNA counts by the 5S rRNA counts on the same filter.

Construction of Infectious cDNA Clones of CMV-Sj and Chimeric Clones between CMV-Y and CMV-Sj

Infectious cDNA clones of CMV-Sj were created essentially as described by Suzuki et al. (1991) for construction of those of CMV-Y. Briefly, genomic RNAs were prepared from the purified virus, and full-length cDNAs were synthesized by RT-PCR using a Takara RNA LA PCR kit (Takara, Otsu, Japan). The 5′ and 3′ end primers used for the RNA3 construction are 5CL3T7G, 5′-CGCTGCAGGATTAATACGACTCACTATAGGTAATCT(T,A)ACCACTGTGTGTG-3′, and 3CL123, 5′-CCGGATCCTGGTCTCCTTTGGA(A,G)GCCCCC-3′, respectively. For RNA1 and RNA2, we used 3CL123 and 5CS12T7G, 5′-CGGGATCCATTAATACGACTCACTATAGTTTATT(T,C)(T,A)CAAGAGCGTA(T,C)GGTTC-3′. The PCR products were then cloned into a plasmid vector. The terminal sequences of the viral RNAs were confirmed by 5′/3′ rapid amplification of cDNA ends. Chimeric clones of RNA2 were created by exchanging the BclI-BlnI fragment (∼600 bp) between CMV-Sj and CMV-Y, generating clones S2(2bY) and clone Y2(2bS). The restriction fragments from Y2 and S2 contain 69 and 72 nucleotides upstream of the 2b gene, respectively. The amino acid sequences of the 2a protein in this region differ by four residues. The 3′ untranslated regions (200 nucleotides of Y2 and 205 nucleotides of S2 downstream of the 2b gene) also were exchanged. The overall sequence identity in the exchanged 3′ untranslated region is ∼80%. RNA1 to RNA3 were in vitro transcribed from each cDNA construct and mixed and inoculated onto N. benthamiana, from which the viruses were purified for further inoculation onto G. max. The composition of the progeny viruses was confirmed by partial sequencing of RT-PCR fragments.

Viral Inoculation and Detection

Plants were maintained in a greenhouse under conditions of a 16-h photoperiod at 24 to 26°C. The first pair of true leaves of G. max was dusted with carborundum and rub-inoculated with the purified virus at 50 μg/mL for CMV or with the sap from an infected leaf for SMV. Plants were scored for symptoms, and viral concentrations were determined either by ELISA or by RNA gel blot analysis. Tissue prints were prepared as essentially described by Masuta et al. (1999). Immature G. max seeds were cut in half and pressed onto a nitrocellulose membrane. The prints were incubated with anti-CMV primary antibody and then with goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin alkaline phosphatase conjugate. The color was developed in the substrate solution containing nitro blue tetrazolium and 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl phosphate.

A. tumefaciens–Mediated Systemic Gene Silencing of GUS

A partial GUS fragment (positions 382 to 1398) was PCR amplified with a primer pair, 5′-BamHI-GTACGTATCACCGTTTGTG-3′ and 5′-XbaI-GTTCAGGCACAGCACATC-3′, and inserted between the BamHI and XbaI sites just upstream of the GUS gene already present in pBI121. Because the PCR product is inserted in the antisense orientation between the two restriction sites, the GUS transcript forms an inverted repeat structure with an ∼400-nucleotide spacer (pBI121-IR-GUS). The recombinant plasmid was then introduced by triparental mating into A. tumefaciens strain KYRT1 (Torisky et al., 1997), which can efficiently infect G. max plants. The strain was kindly provided by G.B. Collins (University of Kentucky). For the control, the empty vector (the GUS gene–deleted pBI121) was introduced in the A. tumefaciens strain. A. tumefaciens harboring pBI121-IR-GUS or the empty vector was grown to stationary phase in L broth containing 100 μg/mL of rifampicin and 200 μg/mL of kanamycin, collected by centrifugation, and resuspended in buffer (10 mM MgCl2, 10 mM Mes, pH 5.7, 150 μg/mL of acetosyringone, and 0.02% Silwet L-77). The Jack-GUS plants were inoculated with CMV onto the first true leaf 7 d before agro-infiltration. Viral infection was confirmed by ELISA and RNA gel blot analysis. After a 3-h incubation of the bacterial preparation, the entire plant was put in a plastic desiccator, all the leaves were immersed in the bacterial solution, and a vacuum of −50 kPa was applied for 10 min. A. tumefaciens was then infiltrated into the leaf by releasing the vacuum. After agro-infiltration, the GUS activity in newly emerging upper leaves was monitored. To investigate the effects of the 2b gene expression in the infiltrated leaves on systemic silencing, A. tumefaciens–mediated transient coexpression of the silencing inducer (pBI121-IR-GUS) and the 2b gene was conducted. Briefly, the 2b cDNA from either CMV-Y or CMV-Sj was inserted downstream of the 35S promoter between XbaI and SacI sites of pBI121 (pBI121-2b), and A. tumefaciens harboring pBI121-2b was coinfiltrated into Jack-GUS plants together with A. tumefaciens carrying pBI121-IR-GUS (silencing inducer). GUS activity in the upper leaves was monitored at 7, 14, and 21 DAI. Four independent plants were used for each treatment.

Sequence data from this article have been deposited with the EMBL/GenBank data libraries under accession numbers M98871, D16248, and X15199.

Acknowledgments

We thank J.J. Finer (Ohio State University) for providing us with Jack and the GUS transgenic line and G.B. Collins for the A. tumefaciens strain. We also thank I. Uyeda (Hokkaido University, Japan), A.O. Jackson (University of California, Berkeley), and P. Palukaitis (Scottish Crop Research Institute, UK) for critical reading of the manuscript. We thank A. Kanazawa (Hokkaido University, Japan) for advice on the nuclear run-on transcription assay and S. Yumoto (Tokachi Agricultural Experimental Station, Japan) and S. Kanematsu (Tohoku National Agricultural Experimental Station, Japan) for the gifts of TH and THM seeds and the antibody against SMV, respectively. This work was supported in part by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology, Japan and research grants from Iijima Memorial Foundation for the Promotion of Food Science and Technology, Japan and Takano Life Science Research Foundation, Japan.

The author responsible for distribution of materials integral to the findings presented in this article in accordance with the policy described in the Instructions for Authors (www.plantcell.org) is: Chikara Masuta (masuta@res.agr.hokudai.ac.jp).

Article, publication date, and citation information can be found at www.plantcell.org/cgi/doi/10.1105/tpc.019885.

References

- Akada, S., and Dube, S.K. (1995). Organization of soybean chalcone synthase gene clusters and characterization of a new member of the family. Plant Mol. Biol. 29, 189–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akada, S., Kung, S.D., and Dube, S.K. (1993). Nucleotide sequence and putative regulatory elements of a nodule-development-specific member of the soybean (Glycine max) chalcone synthase multigene family, Gmchs7. Plant Physiol. 102, 321–323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernard, R.L., and Weiss, M.G. (1973). Qualitative genetics. In Soybeans: Improvement, Production, and Uses, 1st ed., B.E. Caldwell ed (Madison, WI: American Society of Agronomy), pp. 117–154.

- Cogoni, C., and Macino, G. (1999). Gene silencing in Neurospora crassa requires a protein homologous to RNA-dependent RNA polymerase. Nature 399, 166–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalmay, T., Hamilton, A., Mueller, E., and Baulcombe, D.C. (2000). Potato virus X amplicons in Arabidopsis mediate genetic and epigenetic gene silencing. Plant Cell 12, 369–379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding, S.W., Li, W.X., and Symons, R.H. (1995). A novel naturally occurring hybrid gene encoded by a plant RNA virus facilitates long distance virus movement. EMBO J. 23, 5762–5772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fire, A., Xu, S., Montgomery, M.K., Kostas, S.A., Driver, S.E., and Mello, C.C. (1998). Potent and specific genetic interference by double-stranded RNA in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature 391, 806–811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo, H.S., and Ding, S.W. (2002). A viral protein inhibits the long range signaling activity of the gene silencing signal. EMBO J. 21, 398–407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton, A.J., and Baulcombe, D.C. (1999). A species of small antisense RNA in posttranscriptional gene silencing in plants. Science 286, 950–952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton, A.J., Voinnet, O., Chappell, L., and Baulcombe, D.C. (2002). Two classes of short interfering RNA in RNA silencing. EMBO J. 21, 4671–4679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong, J.S., Masuta, C., Nakano, M., Abe, J., and Uyeda, I. (2003). Adaptation of Cucumber mosaic virus soybean strains (CMVs) to cultivated and wild soybeans. Theor. Appl. Genet. 107, 49–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansen, L.K., and Carrington, J.C. (2001). Silencing on the spot. Induction and suppression of RNA silencing in the Agrobacterium-mediated transient expression system. Plant Physiol. 126, 930–938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanazawa, A., O'Dell, M., Hellens, R.P., Hitchin, E., and Metzlaff, M. (2000). Mini-scale method for nuclear run-on transcriptional assay in plants. Plant Mol. Biol. Rep. 18, 377–383. [Google Scholar]

- Kasschau, K.D., and Carrington, J.C. (1998). A counterdefensive strategy of plant viruses: Suppression of posttranscriptional gene silencing. Cell 95, 461–470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennerdell, J., and Carthew, R.W. (1998). Use of dsRNA-mediated genetic interference to demonstrate that frizzled and frizzled 2 act in the wingless pathway. Cell 95, 1017–1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kusaba, M., Miyahara, K., Iida, S., Fukuoka, H., Takano, T., Sassa, H., Nishimura, M., and Nishio, T. (2003). Low glutelin content 1: A dominant mutation that suppresses the glutelin multigene family via RNA silencing in Rice. Plant Cell 15, 1455–1467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, W.X., and Ding, S.W. (2001). Viral suppressors of RNA silencing. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 12, 150–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llave, C., Kasschau, K.D., and Carrington, J.C. (2000). Virus-encoded suppressor of posttranscriptional gene silencing targets a maintenance step in the silencing pathway. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97, 13401–13406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llave, C., Kasschau, K.D., Rector, M.A., and Carrington, J.C. (2002). Endogenous and silencing-associated small RNAs in plants. Plant Cell 14, 1605–1619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallory, A.C., Ely, L., Smith, T.H., Marathe, R., Anandalakshmi, R., Fagard, M., Vaucheret, H., Pruss, G., Bowman, L., and Vance, V.B. (2001). HC-Pro suppression of transgene silencing eliminates the small RNAs but not transgene methylation or the mobile signal. Plant Cell 13, 571–583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallory, A.C., Reinhart, B.J., Bartel, D., Vance, V.B., and Bowman, L.H. (2002). A viral suppressor of RNA silencing differentially regulates the accumulation of short interfering RNAs and micro-RNAs in tobacco. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99, 15228–15233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masuta, C., Nishimura, M., Morishita, H., and Hataya, T. (1999). A single amino acid change in viral genome-associated protein of potato virus Y correlates with resistance breaking in ‘Virgin A Mutant’ tobacco. Phytopathology 89, 119–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metzlaff, M., O'Dell, M., Cluster, P.D., and Flavell, R.B. (1997). RNA-mediated RNA degradation and chalcone synthase A silencing in petunia. Cell 88, 845–854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mlotshwa, S., Voinnet, O., Mette, M.F., Matzke, M., Vaucheret, H., Ding, S.W., Pruss, G., and Vance, V.B. (2002). RNA silencing and the mobile silencing signal. Plant Cell 14 (suppl.), S289–S301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qu, F., Ren, T., and Morris, T.J. (2003). The coat protein of turnip crinkle virus suppresses posttranscriptional gene silencing at an early initiation step. J. Virol. 77, 511–522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santarém, E.R., and Finer, J.J. (1999). Transformation of soybean [Glycine max (L.) Merrill] using proliferative embryogenic tissue maintained on semi-solid medium. In Vitro Cell. Dev. Biol. Plant 35, 451–455. [Google Scholar]

- Senda, M., Jumonji, A., Yumoto, S., Ishikawa, R., Harada, T., Niizeki, M., and Akada, S. (2002. a). Analysis of the duplicated CHS1 gene related to the suppression of the seed coat pigmentation in yellow soybeans. Theor. Appl. Genet. 104, 1086–1091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senda, M., Kasai, A., Yumoto, S., Akada, S., Ishikawa, R., Harada, T., and Niizeki, M. (2002. b). Sequence divergence at chalcone synthase gene in pigmented seed coat soybean mutants of the Inhibitor locus. Genes Genet. Syst. 77, 341–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi, B.-J., Miller, J., Symons, R.H., and Palukaitis, P. (2003). The 2b protein of cucumber mosaic viruses has a role in promoting the cell-to-cell movement of pseudorecombinant viruses. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 16, 261–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki, M., Kuwata, S., Kataoka, J., Masuta, C., Nitta, N., and Takanami, Y. (1991). Functional analysis of deletion mutants of cucumber mosaic virus RNA3 using an in vitro transcription system. Virology 183, 106–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teycheney, P.-Y., and Tepfer, M. (2001). Virus-specific spatial differences in the interference with silencing of the chs-A gene in non-transgenic petunia. J. Gen. Virol. 82, 1239–1243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Todd, J.J., and Vodkin, L.O. (1993). Pigmented soybean (Glycine max) seed coats accumulate proanthocyanidins during development. Plant Physiol. 102, 663–670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Todd, J.J., and Vodkin, L.O. (1996). Duplications that suppress and deletions that restore expression from a chalcone synthase multigene family. Plant Cell 8, 687–699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torisky, R.S., Kovacs, L., Avdiushko, S., Newman, J.D., Hunt, A.G., and Collins, G.B. (1997). Development of a binary vector system for plant transformation based on the supervirulent Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain Chry 5. Plant Cell Rep. 17, 102–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vance, V., and Vaucheret, H. (2001). RNA silencing in plants—Defense and counterdefense. Science 292, 2277–2280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaucheret, H., Beclin, C., Elmayan, T., Feuerbach, F., Godon, C., Morel, J.-B., Mourrain, P., Palauqui, J.-C., and Vernhettes, S. (1998). Transgene-induced gene silencing in plants. Plant J. 16, 651–659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voinnet, O. (2001). RNA silencing as a plant immune system against viruses. Trends Genet. 17, 449–459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voinnet, O., Lederer, C., and Baulcombe, D.C. (2000). A viral movement protein prevents systemic spread of the gene silencing signal in Nicotiana benthamiana. Cell 103, 157–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.S., Todd, J.J., and Vodkin, L.O. (1994). Chalcone synthase mRNA and activity are reduced in yellow soybean seed coats with dominant I alleles. Plant Physiol. 105, 739–748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.S., and Vodkin, L.O. (1994). Extraction of RNA from tissues containing high levels of procyanidins that bind RNA. Plant Mol. Biol. Rep. 12, 132–145. [Google Scholar]

- Waterhouse, P.M., Wang, M.B., and Lough, T. (2001). Gene silencing as an adaptive defence against viruses. Nature 411, 834–842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zabala, G., and Vodkin, L. (2003). Cloning of the pleiotropic T locus in soybean and two recessive alleles that differentially affect structure and expression of the encoded flavonoid 3′ hydroxylase. Genetics 163, 295–309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]