Abstract

Independent component analysis (ICA) is a data-driven approach frequently used in neuroimaging to model functional brain networks. Despite ICA’s increasing popularity, methods for replicating published ICA components across independent datasets have been underemphasized. Traditionally, the task-dependent activation of a component is evaluated by first back-projecting the component to a functional MRI (fMRI) dataset, then performing general linear modeling (GLM) on the resulting timecourse. We propose the alternative approach of back-projecting the component directly to univariate GLM results. Using a sample of 37 participants performing the Multi-Source Interference Task, we demonstrate these two approaches to yield identical results. Furthermore, while replicating an ICA component requires back-projection of component beta-values (βs), components are typically depicted only by t-scores. We show that while back-projection of component βs and t-scores yielded highly correlated results (ρ=0.95), group-level statistics differed between the two methods. We conclude by stressing the importance of reporting ICA component βs so – rather than component t-scores – so that functional networks may be independently replicated across datasets.

Introduction

Independent component analysis (ICA) is a statistical approach for blind separation of a composite multivariate signal into its constituent source signals. ICA has been broadly used in functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to identify task-activated brain networks (Congdon, et al. 2010; McKeown, et al. 1998; Stanger, et al. 2013; Worhunsky, et al. 2013). ICA is frequently followed with general linear modeling (GLM) to assess how these ICA-identified networks are recruited by fMRI tasks (Calhoun, et al. 2001; Kilts, et al. 2013). As a data-driven approach, ICA does not require a priori information about the source signals to identify them; it has thus been used to identify brain networks in the absence of task (i.e. during wakeful rest) in independent samples (Damoiseaux, et al. 2006; Fox, et al. 2005; Wisner, et al. 2013). Disruptions of these “resting-state networks” have been attributed to numerous disorders including schizophrenia, Alzheimer’s disease, and epilepsy (Bullmore, et al. 2010; James, et al. 2013; Sorg, et al. 2009).

The growth of data-sharing initiatives such as the 1000 Functional Connectomes Project and International Neuroimaging Data-sharing Initiative has allowed replication of ICA-derived networks in independent datasets. For example, one may hypothesize that an anterior cingulate network identified from the Stroop task (Stroop 1935) is also recruited by the Flanker task (Eriksen and Eriksen 1974). To test this hypothesis, the cingulate network’s task-related activity could be assessed by back-projecting the component beta-values (component βs) to a participant fMRI dataset, effectively weighting each timepoint by the component. GLM of this weighted dataset would then provide an activity beta-value (activity βs) describing that component’s task-related activation.

However, two barriers impede the replication of ICA-derived networks. First, this approach requires participants’ fMRI datasets. These datasets may not be accessible due to confidentiality issues, and back-projection of ICA components to these datasets can be computationally intensive (particularly for sample sizes > 100). Second, back-projection should be conducted using component βs, but the neuroimaging field traditionally depicts components by t-scores (describing the significance of βs) and rarely reports the βs themselves. While component beta-values and t-scores are generally positively correlated, a voxel could have a small yet highly significant contribution to the component – or conversely, a large yet non-significant contribution.

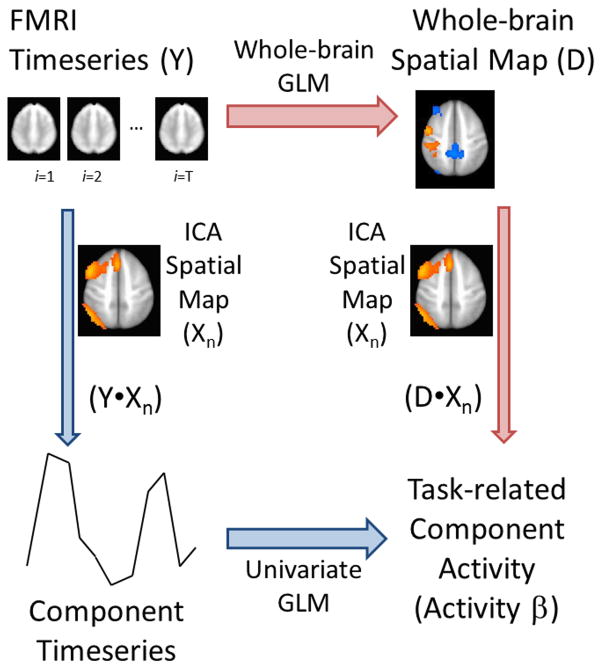

To address the first issue, we propose an alternative approach of directly back-projecting components to univariate (voxelwise) GLM maps, as depicted in Figure 1. Traditionally, the relationship between component and task is determined by (1) back-projecting the component to participant fMRI data to generate a weighted timecourse for that component and (2) using GLM to determine if component activity significantly relates to task (Calhoun, et al. 2001). We propose (1) first assessing task-related activity of participant’s fMRI data with GLM, then (2) back-projecting the ICA component to the resulting GLM map to assess task-related component activity. We assessed the feasibility of our approach by comparing group-level results obtained by each method. To address the second issue, we contrasted results obtained through traditional back-projection of components using (1) voxel beta values or (2) voxel t-statistics.

Figure 1.

Overview of methodological approach. (Blue arrows) Task-based recruitment of an ICA component is traditionally assessed by first back-projecting the ICA spatial map (via multiplication with the nth ICA component’s spatial map) to each timepoint in the fMRI timeseries, thus generating a 1D timeseries weighted by the component. Univariate GLM then determines an activity beta-value (activity βs) and t-score describing that component’s recruitment by one or more task contrasts. (Red arrows) We propose an alternative approach whereby the fMRI timeseries undergoes whole-brain GLM to generate a spatial map for each GLM contrast. The ICA component is then back-projected (again via multiplication) to produce activity βs for that component. Abbreviations: ICA, independent component analysis; fMRI, functional MRI; 1D, one-dimensional; GLM, general linear modeling.

Methods

Participants

Thirty-seven participants (mean±sd age=31±9.9 years; 15 male, 22 female; 21 self-reported as Caucasian, 14 African-American, 1 Hispanic, and 1 as bi-racial; 35 right-handed and 2 left-handed) were selected from participants recruited for a parent study, the Cognitive Connectome Project. Participants were recruited via community advertisements in accordance with University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences Institutional Review Board approval and oversight. Inclusion criteria for the study were healthy men and women, ages 18–50 years, without histories of psychiatric or neurologic illness and who were native English speakers with at least an 8th grade reading and writing proficiency. Exclusion criteria included the presence of psychiatric disorders (with the exception of nicotine dependence) as determined by structured clinical interview (SCID-NP), and contraindications to the high-field MRI environment, such as ferromagnetic implants (determined through a medical history) and pregnancy (determined through a urinalysis).

Procedures

All procedures were conducted in the Brain Imaging Research Center at the Psychiatric Research Institute of the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences. The Cognitive Connectome Project consists of two MRI sessions (1 hour each), a battery of computerized assessments (1 hour) and a comprehensive neuropsychological assessment (3–4 hours). For this work, we analyze data acquired from the Multi-Source Interference Task (MSIT) (Bush and Shin 2006). Of the 48 participants recruited for the Cognitive Connectome, 37 were included in these analyses; 11 participants were excluded for not completing the MSIT scan (n=1), not reporting handedness (n=2), having poor spatial coverage of the brain (n=4), or having excessive head motion (n=4).

Image Acquisition

Participants were scanned using a Philips 3T Achieva X-series MRI scanner (Philips Healthcare, USA). Anatomic images were acquired with a magnetization prepared gradient echo (MPRAGE) sequence (matrix=256×256, 160 sagittal slices, repetition time (TR)=2600ms, echo time (TE)=3.05ms, flip angle (FA)= 8°, final resolution=1×1×1mm3). Functional images were acquired for the first 22 participants using an 8-channel head coil with an echo planar imaging sequence [TR/TE/FA= 2000ms/30ms/90°, field of view= 240×240mm, matrix= 80×80, 37 oblique slices (parallel to orbitofrontal cortex to reduce sinus artifact), slice thickness= 4mm, interleaved slice acquisition, final resolution 3×3×4mm3]. Functional data were acquired on remaining 14 participants after an equipment upgrade to a 32-channel head coil using the same parameters, except thinner slices (slice thickness=2.5mm with 0.5mm gap) and sequential ascending slice acquisition to reduce orbitofrontal signal loss due to sinus cavity artifact.

MSIT

The MSIT was administered as previously described by (Bush and Shin 2006). For each trial, participants viewed a row of three numbers, two of which were identical. Participants indicated which number differed from the other two by pressing a button corresponding to the number’s location (right index, middle, or ring fingers for “1”, “2”, or “3”, respectively). For Congruent trials, the target number’s identity matched its location, and all distracter (non-target) numbers were zeros (i.e. “100”, “020” or “003”). For Incongruent trials, the target number’s identity (1, 2, or 3) did not correspond to its position, and the distracter numbers were also 1s, 2s, or 3s (e.g. “211”, “232”, “331”, etc.). Participants practiced the task to proficiency outside of the MRI scanner prior to performing it inside the scanner.

Stimuli were presented as a block design using Presentation 14.4 (Neurobehavioral Systems Inc.). Each trial lasted approximately 2000 ms and began with a stimulus presentation, lasting for 1750 ms or until participants responded, followed by a fixation cross shown for the remainder of trial. Congruent (Con) and Incongruent (Incon) trials were presented in 4 blocks of 24 trials (48 sec) each, along with three 30 sec Rest blocks. During Rest blocks, participants were instructed to fixate their gaze upon a centrally presented fixation cross and wait for the next trial. The experimental block order was Rest-Con-Incon-Con-Incon-Rest-Con-Incon-Con-Incon-Rest, for a total duration of 480 sec (8 min).

fMRI data preprocessing

Unless otherwise noted, all MRI data preprocessing was performed as previously described (Kilts, et al. 2013) using AFNI version 2011_12_21_1014 (Cox 1996). Anatomic data underwent skull stripping, spatial normalization to the icbm452 brain atlas, and segmentation into white matter, gray matter, and cerebrospinal fluid with FSL (Jenkinson, et al. 2012). Functional data underwent despiking, slice timing correction, deobliquing (to 3×3×3mm3 voxels), motion correction, transformation to the spatially normalized anatomic image, regression of motion parameters, mean timecourse of white matter voxels, and mean timecourse of cerebrospinal fluid voxels, spatial smoothing with a 6mm full-width-half-maximum Gaussian kernel, scaling to percent signal change, and identification and removal of motion-related noise components with Group ICA of fMRI Toolbox (GIFT v1.3) (Calhoun, et al. 2001) for Matlab.

General linear modeling (GLM)

GLM was conducted using AFNI’s 3dDeconvolve program (code available upon request). The GLM modeled Congruent and Incongruent MSIT conditions as 48 sec blocks convolved with AFNI’s default hemodynamical response function, including participant’s head motion parameters (roll, pitch, yaw, and displacement in x, y, and z) as predictors of no interest in the baseline model. A general linear test contrasted Incongruent and Congruent conditions. GLMs were conducted upon fMRI timeseries and upon ICA component timeseries (see below) as depicted in Figure 1.

ICA

ICA components were identified from the preprocessed MSIT data using Matlab and the GIFT v1.3 toolbox. ICA was run using Infomax algorithm and solved for 30 components. The following options were used: back-reconstruction using GICA3, subject-specific principal component analysis using expectation maximization and stacked datasets, full storage of covariance matrix to double precision, usage of selective eigenvariate solvers, two-step data reduction with 50 principal components in the first step, and scaling to z-scores. ICA was repeated 20 times using the ICASSO algorithm to identify the most reliable and stable components across all iterations. The ICASSO stability indices (all iQ>0.95) indicated a reliable solution using 30 components.

Comparing ICA and GLM order effects

Order effects of ICA and GLM were compared as depicted in Figure 1. The traditional approach (shown via blue arrows) calculated the voxelwise product of the nth ICA component (Xn) with each image of an fMRI dataset (Y) to generate an activity timeseries for each component; these components then underwent univariate GLM to identify task-based component activity (activity βs). An alternate approach (red arrows) conducted task-based GLMs for each fMRI dataset (Y), and then calculated the product of the whole-brain spatial map to each ICA component (Xn). Correlational analyses compared similarity of activity βs derived from these two methods.

Comparing component βs and t-scores

The ICA back-projections depicted in Figure 1 were performed using components’ voxelwise β-values as well as components’ voxelwise t-scores. Group-level t-tests calculated task-related change in activity for each component and contrast (Congruent vs. Rest, Incongruent vs. Rest, Congruent vs. Incongruent), with Bonferroni correction for 90 comparisons (30 components × 3 contrasts). Group results were compared between back-projections of component βs and t-scores. Variables such as age, gender, handedness, and acquisition parameters were not modeled as covariates of no interest, since we are comparing results obtained via different methods, and these variables would systemically influence all methods equally.

Univariate GLM

Subjects’ univariate GLM results were analyzed with mixed-effects meta-analysis to generate a univariate group map of MSIT-related brain activity. MSIT-related brain activations have been well-documented elsewhere and are beyond the scope of this study (Bush and Shin 2006). However, these univariate maps may be valuable for interpreting differences between the proposed methods.

Results

Table 1 describes the ICA components generated from the MSIT fMRI task. Twenty-one components resemble neuroanatomical networks previously identified with ICA (Kalcher, et al. 2012). The remaining networks represented noise from head motion or pulsation artifact of cerebrospinal fluid in ventricles and subarachnoid space.

Table 1.

Description of ICA Components

| Comp. | Label | Cluster Size (mm3) ‡ | Peak Voxel Location | Contrast Results using ICA b-values † | Contrast Results using ICA t-scores † | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| x | y | z | Congruent vs. Rest | Incongruent vs. Rest | Incongruent vs. Congruent | Congruent vs. Rest | Incongruent vs. Rest | Incongruent vs. Congruent | |||

| 1 | Noise (cerebral aqueduct) | 241 | −1 | −40 | −34 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | Insulae (bilateral, ventral) | 1,645 | −40 | 11 | −10 | −1 | −1 | 0 | −1 | −1 | 0 |

| 3 | Noise (4th ventricle) | 267 | −1 | −37 | −25 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 4 | Noise (Lateral ventricles) | 1,290 | −4 | 5 | 14 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 5 | Dorsal visual stream | 3,268 | −1 | −82 | 8 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 |

| 6 | Noise (3rd ventricle) | 1,537 | 1 | −22 | 14 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 7 | Cerebellum | 3,037 | 23 | −53 | −19 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 8 | Ventromedial Prefrontal Cortex | 2,808 | −1 | 53 | 8 | −1 | −1 | −1 * | −1 | −1 | 0 * |

| 9 | Posterior Cingulate Cortex | 2,258 | 5 | −49 | 5 | −1 | −1 | −1 * | −1 | −1 | 0 * |

| 10 | Noise (3rd ventricle) | 1,558 | −1 | −22 | −1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 11 | Basal Ganglia | 2,714 | −25 | 8 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 12 | Noise (cerebellar CSF) | 834 | −13 | −28 | −19 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 13 | Corpus Callosum | 1,317 | −4 | 2 | 23 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 14 | Dorsomedial Prefrontal Cortex | 2,237 | −1 | 56 | 29 | 0 | −1 | −1 | 0 | −1 | −1 |

| 15 | Amygdala and Hippocampus (bilateral) | 1,898 | −10 | −4 | −13 | 0 | −1 | −1 | 0 | −1 | −1 |

| 16 | Noise (Superior Sagittal sinus) | 2,431 | −1 | −40 | −71 | −1 | −1 | 0 | −1 | −1 | 0 |

| 17 | Superior Temporal Sulci (bilateral) | 3,524 | −58 | −19 | 14 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 |

| 18 | Ventral visual stream | 3,015 | 26 | −76 | −19 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 19 | Left primary motor and right cerebellum | 2,877 | −34 | −16 | 68 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 20 | Default Mode Network | 2,476 | −1 | −43 | 23 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 |

| 21 | Noise (cerebellar CSF) | 1,072 | 3 | −38 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 22 | Left frontoparietal | 3,711 | −43 | 44 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 23 | Right frontoparietal | 3,519 | 47 | 14 | 47 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 24 | Noise (cerebellar CSF) | 1,164 | −4 | −37 | −7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 25 | Brain stem | 530 | −1 | −10 | −16 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 26 | Inferior frontal and middle temporal (bilateral) | 3,363 | 56 | −52 | 17 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 |

| 27 | Lateral premotor (bilateral) | 1,211 | 53 | −10 | 32 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 28 | Anterior cingulate and pre-SMA | 2,790 | −1 | 20 | 41 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 29 | SMA | 2,263 | −1 | −19 | 50 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 |

| 30 | Noise (ventricles) | 2,449 | −1 | 17 | 11 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Contrast differs when using ICA b-values or ICA t-scores;

+1 indicates more activity for contrast, −1 indicates less activity for contrast, 0 indicates no significant difference;

Volume of largest cluster in component; for bilateral components, represents the sum of left and right clusters (ex: left and right insulae for component 2)

Activity βs were identical whether obtained (a) via back-projection of ICA components to subject fMRI data then GLM or (b) via whole-brain GLM of subject fMRI data then back-projection of ICA components. These activity βs were perfectly correlated (r=1.00) and differed only by rounding error.

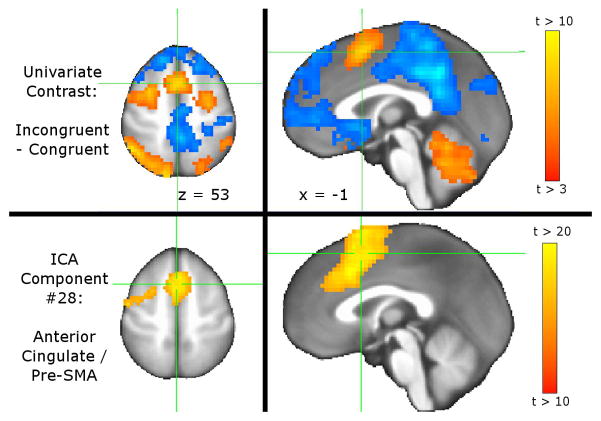

Activity βs were highly correlated whether obtained via back-projection of (a) ICA component βs or (b) ICA component t-scores. The mean±sd correlation was 0.95±0.08 across all 30 components and 3 contrasts, with a correlation range of 0.68–0.99. Correlations were higher for the 21 non-noise components: mean±sd= 0.98±0.04, range 0.79–0.99. Although highly correlated, two-sample Kolmogorov-Smirnov goodness-of-fit tests showed component βs and t-scores to arise from significantly different distributions (minimum Kolmogorov-Smirnov statistic = 0.341 for component 22, all component p<0.001).GLT results were largely consistent for activity βs obtained via back-projection of (a) component βs or (b) component t-scores. Both methods found the anterior cingulate component (#28) as significantly more active during Incongruent vs. Congruent contrast, as previously reported (Bush and Shin 2006). The univariate GLM showed MSIT-related cingulate activation to be more superior than typically reported, encompassing pre-SMA and peri-cingulate rather than anterior cingulate proper (Figure 2). By comparison, the anterior cingulate component (#28) includes pre-SMA and peri-cingulate as well as dorsal anterior cingulate. This component also captures some left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, which is also present in the univariate contrast.

Figure 2.

Contrasting overlap of cingulate ICA component with univariate GLM map. (Top) Mixed effects meta-analysis of individual subjects’ univariate GLM generated a group map of brain regions with differing activity between Incongruent and Congruent MSIT conditions. Results are thresholded at uncorrected p<0.005, minimum cluster size=39 contiguous voxels for FDR corrected α=0.05. Crosshairs depict the most significant voxel in the peri-cingulate / pre-SMA cluster. (Bottom) Of the 30 ICA components, #28 has best spatial coverage of anterior cingulate. This component includes peri-cingulate, pre-SMA, dorsal anterior cingulate, and left dorsolateral prefrontal. Images are presented in neurological convention.

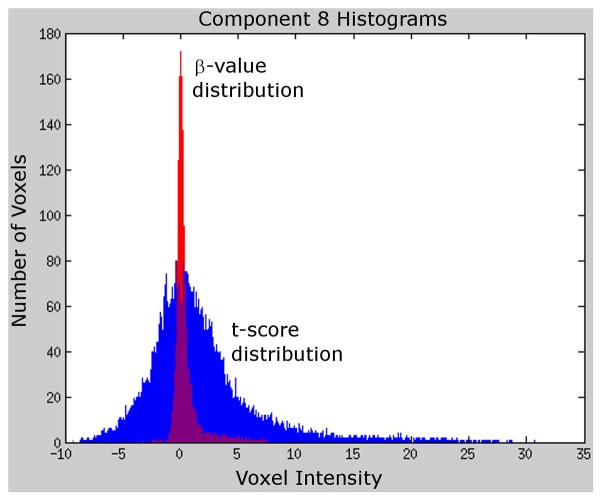

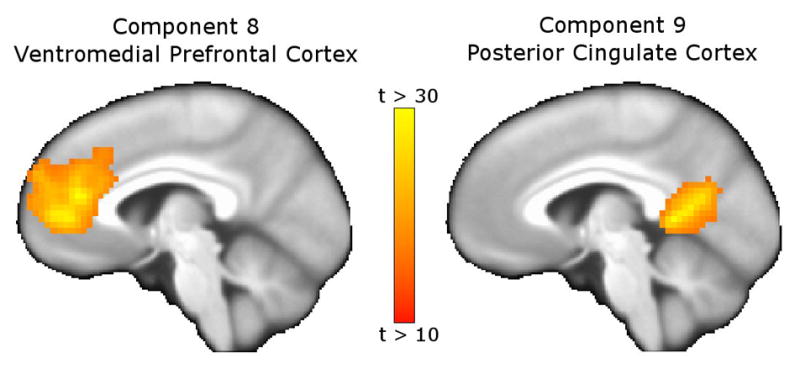

However, activity βs differed between methods for two components: the ventromedial prefrontal cortex (#8) and posterior cingulate (#9). Both were significantly less active during Incongruent vs. Congruent contrast when back-projecting component βs but not significantly different when back-projecting t-scores. Figure 3 depicts sagittal views of these components. Figure 2 shows the regions encompassed by these components to be task deactivated for the univariate contrast; the component β method (but not the component t-score method) also found these components to be task deactivated. We attribute these differing results to the aforementioned differences in component βs and t-score distributions, which are depicted for Component 8 in Figure 4. The component β distribution shows higher kurtosis and lower variance than the t-score distribution, which accounts for differences in GLM findings.

Figure 3.

Components with differing GLM contrast results when back-projecting ICA component βs vs. component t-scores. Components 8 (ventromedial prefrontal cortex and rrostral cingulate, left) and 9 (posterior cingulate cortex, right) showed task-related deactivation for the Incongruent vs. Congruent contrast when back-projecting component βs, but no difference in activation when back-projecting component t-scores. As shown in Figure 2, these regions were deactivated for the univariate Incongruent vs. Congruent contrast, supporting the back-projection of component βs as more reliable than back-projection of component t-scores.

Figure 4.

Histograms of ICA component β-values and t-scores. Histograms depict the frequency of voxel intensities for ICA component 8 β-values (red) and t-scores (blue). The distribution of β-values has less variance and greater kurtosis than the distribution of t-scores. These differences in distributions account for the differing results obtained when back-projecting component β-values compared to back-projecting component t-scores. Two-sample Kolmogorov-Smirnov goodness-of-fit tests showed the distributions of βs and t-scores to significantly differ for all components (p<0.001)

Discussion

We have demonstrated that our novel approach of back-projecting ICA components to GLM maps yields identical results as the traditional approach. Our approach was developed as a means for replicating ICA components in the parent Cognitive Connectome project without requiring back-projection of each component to each timepoint of each fMRI dataset, which is the most computationally intensive aspect of the traditional approach. For the MSIT fMRI task with 240 timepoints and 3 GLM contrasts, our ICA approach is approximately 80-times faster than the traditional approach. Using a 1 GHz processor, back-projecting 30 components to one MSIT fMRI dataset took 40s with the traditional approach and <1s with the novel approach. While these savings are small, they add up with large sample sizes and multiple fMRI tasks, as is the trend in Big Data initiatives.

These calculations assume that univariate GLM maps already exist. We estimate a single subject’s univariate GLM to take approximately 20s, halving the estimated efficiency of the novel approach for situations where GLM maps do not already exist. Furthermore, computer processing speed, number of timepoints, and number of GLM contrasts can influence computation time. But given that the typical fMRI dataset has an order of magnitude more timepoints than contrasts (i.e. 100–300 timepoints and 1–10 contrasts), we still contend this approach to be more efficient than the traditional approach.

A caveat of this approach is that it only provides activity βs for each participant, whereas the traditional approach provides activity βs and t-statistics. Subject-level statistics may be valuable for descriptive purposes, such as determining what percentage of the sample had a significantly active component. But for group-level statistics, such as determining if component activity significantly differs from zero, these methods produce identical results. The same holds for individual differences research, such as asking if component activity scales with a demographic variable such as age or education.

We also demonstrate that, while back-projecting ICA components’ βs and t-scores yield highly correlated activity βs (particularly for non-noise components), these approaches lead to differing GLM results. We attribute these findings to differences in the distributions of component βs and t-scores. For each component, the distribution of βs had less variance and greater kurtosis than t-scores, as is depicted in Figure 4 for component 8. These distribution differences could easily result in false positives and false negatives, reinforcing the need to use component βs over t-scores. Furthermore, back-projection of component βs for components 8 and 9 showed task-related deactivation of these components, which is consistent with the univariate GLM results depicted in Figure 2 – providing additional evidence for back-projecting component βs rather than component t-scores.

A limitation to our second finding is that GLM and ICA βs are rarely reported. We acknowledge that the neuroimaging audience has more experience interpreting t-statistics, and thus these may be better suited for publication than βs. Nonetheless, we encourage authors to make GLM and ICA βs publicly available, whether as Supplementary Materials, through data-sharing initiatives, or by request.

Conclusions

We conclude by stressing the need to replicate neuroimaging findings across independent samples. Historically, the expense and inaccessibility of MRI scanners has caused functional neuroimaging to garner the reputation as generating “more heat than light”. The recent growth of data sharing initiatives provides an opportunity to refute this reputation. Toward this aim, our research highlights advantages and pitfalls to replicating ICA findings across samples.

Highlights.

ICA traditionally back-projects component betas to fMRI data then estimates GLM

We instead back-projected ICA components to the GLMs, with identical results

Neuroimaging publications typically report component t-scores but not betas

We obtained different results when back-projecting component t-scores vs. betas

Replication of ICA components should use betas rather than t-scores

Acknowledgments

We thank Jonathan Young, M.A. and Sonet Smitherman, B.S. for MRI scanner operation, recruitment, and maintaining institutional compliance. This work was supported by the KL2 Scholars Program (PI James; KL2TR000063) and the UAMS Translational Research Institute (UL1TR000039).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Bullmore E, Lynall ME, Bassett DS, Kerwin R, McKenna PJ, Kitzbichler M, Muller U. Functional Connectivity and Brain Networks in Schizophrenia. Journal of Neuroscience. 2010;30(28):9477–9487. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0333-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bush G, Shin LM. The Multi-Source Interference Task: an fMRI task that reliably activates the cingulo-frontal-parietal cognitive/attention network. Nat Protoc. 2006;1(1):308–13. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calhoun VD, Adali T, Pearlson GD, Pekar JJ. A method for making group inferences from functional MRI data using independent component analysis. Human brain mapping. 2001;14(3):140–51. doi: 10.1002/hbm.1048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Congdon E, Mumford JA, Cohen JR, Galvan A, Aron AR, Xue G, Miller E, Poldrack RA. Engagement of large-scale networks is related to individual differences in inhibitory control. NeuroImage. 2010;53(2):653–663. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.06.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox RW. AFNI: software for analysis and visualization of functional magnetic resonance neuroimages. Computers and biomedical research, an international journal. 1996;29(3):162–73. doi: 10.1006/cbmr.1996.0014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damoiseaux JS, Rombouts SA, Barkhof F, Scheltens P, Stam CJ, Smith SM, Beckmann CF. Consistent resting-state networks across healthy subjects. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2006;103(37):13848–53. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601417103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eriksen BA, Eriksen CW. Effect of noise letters upon identification of a target letter in a non-search task. Perception and Psychophysics. 1974;16:143–149. [Google Scholar]

- Fox MD, Snyder AZ, Vincent JL, Corbetta M, Van Essen DC, Raichle ME. The human brain is intrinsically organized into dynamic, anticorrelated functional networks. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2005;102(27):9673–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504136102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James GA, Tripathi SP, Ojemann JG, Gross RE, Drane DL. Diminished default mode network recruitment of the hippocampus and parahippocampus in temporal lobe epilepsy. J Neurosurg. 2013 doi: 10.3171/2013.3.JNS121041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkinson M, Beckmann CF, Behrens TE, Woolrich MW, Smith SM. Fsl. NeuroImage. 2012;62(2):782–90. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalcher K, Huf W, Boubela RN, Filzmoser P, Pezawas L, Biswal B, Kasper S, Moser E, Windischberger C. Fully exploratory network independent component analysis of the 1000 functional connectomes database. Front Hum Neurosci. 2012;6:301. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2012.00301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilts CD, Kennedy A, Elton AL, Tripathi SP, Young J, Cisler JM, James GA. Individual Differences in Attentional Bias Associated with Cocaine Dependence Are Related to Varying Engagement of Neural Processing Networks. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2013 doi: 10.1038/npp.2013.314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKeown MJ, Jung TP, Makeig S, Brown G, Kindermann SS, Lee TW, Sejnowski TJ. Spatially independent activity patterns in functional MRI data during the stroop color-naming task. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1998;95(3):803–10. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.3.803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorg C, Riedl V, Perneczky R, Kurz A, Wohlschlager AM. Impact of Alzheimer’s disease on the functional connectivity of spontaneous brain activity. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2009;6(6):541–53. doi: 10.2174/156720509790147106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanger C, Elton A, Ryan SR, James GA, Budney AJ, Kilts CD. Neuroeconomics and adolescent substance abuse: individual differences in neural networks and delay discounting. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2013;52(7):747–755. e6. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2013.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stroop JR. Studies of interference in serial verbal reactions. Journal of Experimental Psychology. 1935;18(6):643–662. [Google Scholar]

- Wisner KM, Atluri G, Lim KO, Macdonald AW., 3rd Neurometrics of intrinsic connectivity networks at rest using fMRI: retest reliability and cross-validation using a meta-level method. NeuroImage. 2013;76:236–51. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.02.066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Worhunsky PD, Stevens MC, Carroll KM, Rounsaville BJ, Calhoun VD, Pearlson GD, Potenza MN. Functional brain networks associated with cognitive control, cocaine dependence, and treatment outcome. Psychol Addict Behav. 2013;27(2):477–88. doi: 10.1037/a0029092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]