Abstract

Background

There are limited data regarding the relationship between depression and mortality in hemodialysis patients.

Methods

Among 323 maintenance hemodialysis patients, depression symptoms were assessed using the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression (CES-D) scale, with a score of ≥16 consistent with depression. Adjusted Cox proportional hazards models, with additional analyses incorporating antidepressant medication use, were used to evaluate the association between depression and mortality. Baseline CES-D scores were used for primary analyses, while secondary time dependent analyses incorporated subsequent CES-D results.

Results

Mean age was 62.9 ± 16.5 years, 46% were women and 22% African American. Mean baseline CES-D score was 10.7 ± 8.3, and 83 (26%) participants had CES-D scores ≥16. During median (25th, 75th) follow-up of 25 (13, 43) months, 154 participants died. After adjusting for age, sex, race, primary cause of kidney failure, dialysis vintage and access, baseline depression was associated with an increased risk of all-cause mortality [HR (95% CI)=1.51 (1.06, 2.17)]. This attenuated with further adjustment for cardiovascular disease, smoking, Kt/V, serum albumin, log CRP and antidepressant use [HR=1.21 (0.82, 1.80)]. When evaluating time-dependent CES-D, depression remained associated with increased mortality risk in the fully adjusted model [HR=1.44 (1.00, 2.06)].

Conclusions

Greater symptoms of depression are associated with an increased risk of mortality in hemodialysis patients, particularly when accounting for the most proximate assessment. This relationship was attenuated with adjustment for comorbid conditions, suggesting a complex relationship between clinical characteristics and depression symptoms. Future studies should evaluate whether treatment for depression impacts mortality among HD patients.

Keywords: All-cause mortality, antidepressant medication use, depression, hemodialysis

Introduction

Depression is common among people with chronic kidney disease (CKD), with an estimated prevalence of 21% to 27% in non-dialysis CKD [1]. The prevalence of depression likely is higher among hemodialysis patients, with estimated rates ranging from 23% to 42% in the US and Europe [1–3]. In the general population, depression is associated with an increased risk of mortality; a similar association has been noted in non-dialysis CKD [4–6].

Among hemodialysis patients, limited data exist, with many studies relying on administrative diagnoses of depression, few including data on antidepressant medication and few having sequential depression screening. Several studies have shown that patients with depression had lower quality of life, more functional impairment, greater comorbidity and psychopathologic states, lower treatment compliance, and an increased risk of both hospitalization and mortality [3, 7–12]. Notable among these studies, most of which rely on self-reported symptoms, is one study of 98 hemodialysis patient where depression, diagnosed by structured clinical interviews performed by physicians, was associated with mortality [2]. In the largest study to date, an analysis of hemodialysis patients in the Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patients Study (DOPPS, n= 5256), either physician-diagnosed or self-reported depression was associated with increased risks of both mortality and hospitalization [9]. Depression in this study was defined by either an administrative diagnosis of depression or answers to two self-response questions from the Kidney Disease and Quality of Life Short Form (KDQOL-SF).

Few studies have examined repeated measurements of depression symptoms, and these studies, both of which showed an association between time varying but not baseline depression symptoms and mortality, differ importantly from the current study by use of a more limited instrument for evaluating depression and by evaluation of an exclusively urban, African American population [13, 14]. Accordingly, we evaluated the relationship between depression, assessed using a validated depression screening instrument at baseline and annually thereafter, and all-cause mortality in a large generalizable cohort of maintenance hemodialysis patients, further exploring the role of time-dependent screening and antidepressant medication use. Given that hemodialysis patients with depression symptoms have a higher occurrence of cognitive impairment [10], lower adherence to dietary fluid restrictions, medications and dialysis treatments [15, 16], and an increased risk of hospitalization [17], we hypothesized that a greater burden of depression symptoms is associated with an increased risk of all-cause mortality in hemodialysis patients.

Methods

Participants and Data Collections

Patients receiving hemodialysis at five Dialysis Clinic Inc. (DCI) units and one hospital based unit (St Elizabeth’s Medical Center) in the greater Boston area, MA, were considered for the Cognition and Dialysis Study. Participants who were eligible for this study included English fluency, sufficient visual and hearing acuity to complete cognitive testing. Exclusion criteria were individuals with pre-existing advanced dementia based on provider testimony or medical record review, non vascular access related hospitalization within 1 month, delirium, receipt of maintenance hemodialysis for less than 1 month, and single-pool Kt/V (spKt/V) <1.0.

Demographic, clinical and laboratory characteristics were ascertained at the time of study enrollment. Demographic and clinical characteristics were obtained though participants report, medical charts, and the DCI and St. Elizabeth Medical Center databases. Blood pressure was defined as mean pre-dialysis blood pressure for the month prior to the baseline visit, and body mass index (BMI) was calculated using pre-dialysis weight. Laboratory tests including hematocrit, white blood cell count (WBC), serum albumin, and single pool Kt/V were obtained from the DCI or St. Elizabeth’s electronic record. All DCI laboratory tests were measured in a central laboratory in Nashville, TN. High sensitivity C- reactive protein (CRP) was measured from frozen sera obtained at study enrollment. Antidepressant medication use was obtained from electronic database; medications included selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, tricyclic antidepressants, dopamine/norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (buproprion), noradrenergic and serotonergic agonists (mirtazapine), serotonin/norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (venlafaxine), and serotonin modulators (nefazodone and trazodone). The Tufts Medical Center/Tufts University Institutional Review Board approved the study and all participants signed informed consent and research authorization forms.

Depression Symptom Assessment

All participants were administered the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression (CES-D) scale as a part of a broader neurocognitive assessment. Neurocognitive testing was performed by trained research assistants, with testing observed by the study neuropsychologist at 3–6 month intervals to maintain quality and inter-rater reliability. To limit participant fatigue, neurocognitive testing was completed during the first hour of hemodialysis.

The Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression (CES-D) scale is a validated self-reported questionnaire comprised of 20 questions, with higher scores indicating a greater burden of depression symptoms. In the general population, a CES-D score ≥16 is considered to be consistent with major depression [18], while, in hemodialysis patients where somatic symptoms are more common, one analysis showed greater diagnostic accuracy with a threshold of 18 [19]. Accordingly, in primary analyses we define a high depression symptom burden as a CES-D score of ≥16 while sensitivity analyses use a threshold CES-D score of ≥18 and also explore the CES-D score as a continuous variable reporting the association of each one standard deviation change (8.3 points) in CES-D score with mortality.

Outcome

The primary outcome was all-cause mortality, which was obtained from electronic medical record monitoring as well as contact with each patient’s dialysis unit. We defined survival time for each participant as time from enrollment to the earliest of death, transplantation, or end of study follow-up (March 31th, 2013).

Covariates

A priori selected covariates included demographic characteristics (age, race and sex); primary cause of kidney failure (diabetes versus non-diabetes); dialysis vintage; dialysis access (fistula versus non-fistula); history of cardiovascular disease (either coronary artery disease, peripheral vascular disease, stroke, or heart failure); smoking; spKt/V; serum albumin; CRP; and baseline antidepressant medication use.

Statistical analyses

Participants were stratified according to baseline CES-D score of 16, and baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of participants with or without depression symptoms were compared using chi squared tests for categorical variables and t-tests or the Mann-Whitney U test for continuous variables, as appropriate.

Cox proportional hazards regression models were used to evaluate the association of CES-D score and all-cause mortality. Cox regression models A PRIORI were adjusted following potential confounders: 1) Model 1: age, sex and race; 2) Model 2: model 1 plus primary cause of kidney failure, dialysis access, and dialysis vintage; 3) Model 3: model 2 plus history of cardiovascular disease and smoking status; and 4) Model 4: model 3 plus spKt/V, serum albumin, log transformed CRP and baseline antidepressant medication use. Variables not included A PRIORI or not significant in univariate analyses, such as blood pressure, were not included in sequentially adjusted models. In secondary analyses to account for change in CES-D scores over time, Cox models incorporated time-dependent CES-D scores measured annually, carrying the last score forward between each successive visit. We also explored A PRIORI the interaction between baseline CES-D score and antidepressant medication use, as antidepressant medications could modify the CES-D score and its relationship with mortality. All analyses were performed using SAS (version 9.3, SAS Institute, Cary, NC) and R package (version 2.15.1).

Results

Baseline characteristics

Among 323 participants, mean age was 62.9 ± 16.5 years, 46% were female, 22% were African American, and 33% had diabetes as primary cause of kidney failure; 61% had a history of CVD and 61% had a history of smoking, with 9% of these current smokers. Median (25th, 75th) dialysis vintage was 14.1 (6.8, 33.8) months, and 65% used a fistula as vascular access (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of participants

| Variable | Total n=323 | CES-D score < 16 n=240 (74%) | CES-D score ≥ 16 n=83 (26%) | P - value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CES-D score | 10.7 ± 8.3 | 6.8 ± 4.3 | 22.2 ± 5.8 | <0.001 |

| Age (y) | 62.9 ± 16.5 | 63.2 ± 16.5 | 62.0 ± 16.6 | 0.60 |

| Female (%) | 150 (46.4) | 112 (46.7) | 38 (45.8) | 0.89 |

| African American (%) | 71 (22.0) | 52 (21.7) | 19 (22.9) | 0.82 |

| Primary cause of ESRD (%) | 0.03 | |||

| Diabetes | 107 (33.1) | 77 (32.1) | 30 (36.1) | |

| Hypertension | 59 (18.3) | 48 (20.0) | 11 (13.3) | |

| Glomerular disease | 55 (17.0) | 47 (19.6) | 8 (9.6) | |

| Other | 52 (16.1) | 38 (15.8) | 14 (16.9) | |

| Unknown | 50 (15.5) | 30 (12.5) | 20 (24.1) | |

| History of CVD (%) | 198 (61.3) | 141 (58.8) | 57 (68.7) | 0.11 |

| Smoking status (%) | 0.04 | |||

| Current | 29 (9.1) | 17 (7.1) | 12 (14.6) | |

| Past | 167 (52.2) | 121 (50.8) | 46 (56.1) | |

| Never | 124 (38.8) | 100 (42.0) | 24 (29.3) | |

| Vascular access (%) | 0.24 | |||

| Fistula | 211 (65.3) | 158 (65.8) | 53 (63.9) | |

| Graft | 18 (5.6) | 16 (6.7) | 2 (2.4) | |

| Catheter | 94 (29.1) | 66 (27.5) | 28 (33.7) | |

| Dialysis vintage (month) | 14.1 (6.8, 33.8) | 13.6 (6.9, 35.4) | 15.3 (6.4, 30.7) | 0.73 |

| Systolic BP (mmHg) | 141.3 ± 20.8 | 141.3 ± 20.4 | 141.3 ± 21.8 | 0.98 |

| Diastolic BP (mmHg) | 73.3 ± 12.1 | 73.3 ± 11.9 | 73.2 ± 12.6 | 0.93 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 28.4 ± 7.0 | 28.1 ± 6.9 | 29.2 ± 7.3 | 0.22 |

| Hematocrit (%) | 35.5 ± 3.5 | 35.6 ± 3.5 | 35.1 ± 3.5 | 0.25 |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 3.8 ± 0.4 | 3.8 ± 0.4 | 3.7 ± 0.4 | 0.03 |

| WBC (mcL) | 7.4 ± 2.3 | 7.4 ± 2.4 | 7.5 ± 2.3 | 0.64 |

| CRP (mg/L) | 5.3 (2.2, 11.5) | 4.9 (1.9, 9.8) | 6.5 (2.6, 18.5) | 0.05 |

| spKt/V | 1.51 ± 0.24 | 1.53 ± 0.25 | 1.46 ± 0.21 | 0.02 |

| Antidepressant use (%) | 138 (42.7) | 90 (37.5) | 48 (57.8) | 0.001 |

Data are present as mean ± SD, number (present) or median (25th, 75th). Conversion factors for units: albumin in g/dL to g/L, ×10; phosphorus in mg/dL to mmol/L, ×0.3229.

Abbreviations: CES-D, Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scales; ESRD, end stage renal disease; CVD, cardiovascular disease; BP, blood pressure; BMI, body mass index; WBC, white blood cell; CRP, C-reactive protein; spKt/V, single pool Kt/V

For each participant, a median of 2 (25th–75th percentile, 1 – 3) CES-D assessments occurred. Mean CES-D score at the baseline, 2nd and 3rd visit were 10.7 ± 8.3 (n=323), 10.9 ± 8.7 (n=196) and 12.3 ± 9.6 (n=121), respectively. Eighty-three (26%) participants had CES-D scores ≥16 at baseline and 42.7% were treated with an antidepressant medication at baseline. In individuals prescribed antidepressant medications, 90 (65.2%) had baseline CES-D scores below 16 while 48 (34.8%) had scores of 16 or higher (P=0.002). Participants with a higher CES-D score at baseline were more likely to have diabetes as primary cause of kidney failure and a history of smoking, to have lower serum albumin and spKt/V, and to be receiving antidepressant medications (Table 1).

Depression symptoms and all-cause mortality

During median (25th, 75th) follow-up of 25 (13, 43) months, 154 participants died. In participants with baseline CES-D score <16, there were 17.7 deaths per 100-patient years while, for individuals with baseline CES-D score ≥16, there were 23.3 deaths per 100-patient years. After adjustment for age, sex and race, depression was associated with an increased risk of all-cause mortality [HR (95% CI)=1.50 (1.05, 2.14)]; this association remained significant after further adjustment for primary cause of kidney failure, dialysis access and vintage [HR (95% CI)=1.51 (1.06, 2.17)]. After further adjustment for history of cardiovascular history and smoking, this relationship was attenuated [HR (95% CI)=1.39 (0.96, 2.00)], and in models that also included serum albumin, CRP and antidepressant medications, the relationship was no longer significant [HR (95% CI)=1.21 (0.82, 1.80)] (Table 2). Results were similar when a baseline CES-D threshold of ≥ 18 and when a continuous term for CES-D was used (Table 2).

Table 2.

Association between baseline CES-D score and all-cause mortality

| Events per 100-patient yrs | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | P-value | Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | P-value | Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | P-value | Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | P-value | ||

| CES-D score ≥ 16 | 23.3 vs 17.7 | 1.50 (1.05, 2.14) | 0.03 | 1.51 (1.06, 2.17) | 0.02 | 1.39 (0.96, 2.00) | 0.08 | 1.21 (0.82, 1.80) | 0.34 |

| CES-D score ≥ 18 | 24.1 vs 17.9 | 1.67 (1.13, 2.48) | 0.01 | 1.68 (1.13, 2.50) | 0.01 | 1.46 (0.97, 2.18) | 0.07 | 1.27 (0.82, 1.98) | 0.29 |

| CES-D score (per 1 SD higher) | Overall 19.0 | 1.25 (1.05, 1.48) | 0.01 | 1.26 (1.06, 1.50) | 0.008 | 1.20 (1.01, 1.42) | 0.04 | 1.13 (0.94, 1.35) | 0.21 |

Each standard deviation for CES-D score is 8.3. Model 1 is adjusted for age, sex and race. Model 2: Model 1+ primary cause of kidney failure, dialysis access, and dialysis vintage. Model 3: Model 2 + history of cardiovascular disease and smoking status. Model 4: Model 3 + spKt/V, serum albumin, log CRP, and baseline antidepressant medication use.

The association of CES-D score with all-cause mortality was robust when CES-D score was treated as a time-dependent variable (Table 3). Participants with a CES-D score of 16 or higher had a higher risk of all-cause mortality in an age, sex and race adjusted model [HR (95% CI)=1.55 (1.10, 2.17)], with a similar effect size maintained in further adjusted models. Results were similarly robust in time dependent models when using a CES-D threshold of 18, in analyses examining CES-D score as a continuous variable, and when examining cardiovascular versus non-cardiovascular causes of death (data not shown).

Table 3.

Association between time-dependent CES-D score and all-cause mortality

| Events per 100-patient years | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | P-value | Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | P-value | Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | P-value | Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | P-value | ||

| CES-D score ≥ 16 | 23.3 vs 17.7 | 1.55 (1.10, 2.17) | 0.01 | 1.54 (1.09, 2.16) | 0.01 | 1.47 (1.04, 2.08) | 0.03 | 1.44 (1.00, 2.06) | 0.05 |

| CES-D score ≥ 18 | 24.1 vs 17.9 | 1.49 (1.02, 2.17) | 0.04 | 1.48 (1.01, 2.16) | 0.05 | 1.40 (0.95, 2.05) | 0.09 | 1.36 (0.91, 2.03) | 0.14 |

| CES-D score (per 1 SD higher) | Overall 19.0 | 1.24 (1.06, 1.44) | 0.006 | 1.25 (1.07, 1.46) | 0.004 | 1.23 (1.05, 1.43) | 0.008 | 1.21 (1.04, 1.42) | 0.02 |

Each standard deviation for CES-D score is 8.3. Model 1 is adjusted for age, sex and race. Model 2: Model 1 + primary cause of kidney failure, dialysis access, and dialysis vintage. Model 3: Model 2 + history of cardiovascular disease and smoking status. Model 4: Model 3 + spKt/V, serum albumin, log CRP, and baseline antidepressant medication use.

Antidepressant medication use, depression and all-cause mortality

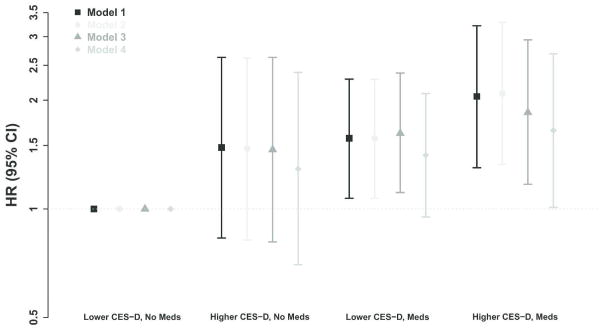

There was no significant interaction between baseline CES-D score and antidepressant medicine use (P-values for interaction were 0.74, 0.80, 0.52, and 0.80 in models 1 to 4, respectively). Figure 1 shows the association among depression defined by a CES-D threshold of ≥16, baseline antidepressant medication use and all-cause mortality. Depressed individuals who were prescribed antidepressants had significantly higher risk of all-cause mortality in all models compared to those with CES-D score <16 not receiving antidepressants. Similar results were found using a CES-D score threshold of ≥18 (Supplementary Figure S1).

Figure 1.

Association among CES-D score ≥16, antidepressant medication prescription and all-cause mortality. Error bars show the 95% confidence interval. Model 1: adjusted for age, sex and race. Model 2: model 1 plus primary cause of kidney failure, dialysis access, and dialysis vintage. Model 3: model 2 plus history of cardiovascular disease, and smoking status. Model 4: model 3 plus spKt/V, serum albumin, and log CRP.

Discussion

In current study we demonstrate that a greater depression symptom burden is associated with an increased risk of all-cause mortality in maintenance hemodialysis patients. This association was attenuated following multivariable adjustment for cardiovascular disease and inflammation and nutrition markers, factors that may be on the causal pathway linking depression and mortality, although in models incorporating the most proximate measure of the CES-D to study completion, depression remained independently associated with mortality, even following adjustment. We also noted that there was no interaction between baseline depression and antidepressant medication use, although individuals receiving medications who also had a high CES-D score were at highest risk.

Given the effects on quality of life and medical outcomes, depression screening has been proposed by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services in the US as a quality indicator [20] while the KDOQI guideline for cardiovascular disease in dialysis patients suggests evaluating patients’ psychological states at least biannually with specific focus on the presence of depressive symptoms [21]. Despite this, as recently reviewed by Hedayati and colleagues [22], depression screening and treatment likely remain insufficient within the dialysis population [8, 17].

Prior studies have demonstrated a relationship between depression and mortality [4], although, in many studies, the relation is attenuated after multivariable adjustment, possibly reflecting mediating factors. In the non dialysis CKD population, a recent meta-analysis of 22 cohort studies including 83,381 individuals showed that depression was associated with a 59% higher risk of all-cause mortality [6], while in individuals treated with hemodialysis, a second meta-analysis including 41,941 participants in 25 studies, similarly demonstrated that a higher burden of depression symptoms was associated with an increased risk of mortality [23]. These two meta-analyses had similar limitations, with heterogenous depression ascertainment methods, varying time between ascertainment and outcomes, reliance on a single assessment and absence of medication use data. Few studies have evaluated repeated assessments of depression symptoms. Boulware and colleagues performed a post hoc analysis of the Choices for Healthy Outcomes in Caring for ESRD (CHOICE) study. Using responses to questions on the Short Form-36 (SF-36), they assessed symptoms at four 6-month intervals and noted that, among 917 incident dialysis patients, persistent symptoms of depression were associated with a greater risk of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality; this association was not significant when defining depression only using the baseline assessment[14]. Similar results were reported in an analysis for 295 chronic hemodialysis patients, such that time-vary depression symptoms assessed using the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) and the Cognitive Depression Index (CDI), but not baseline depression symptoms, was associated with an increased risk of mortality [13].

Our primary results demonstrate that greater depression symptoms at baseline are associated with an increased risk of all-cause mortality in maintenance HD patients, but this association was attenuated with further adjustment for comorbidity. There are several potential interpretations of this finding. First, depression itself may increase mortality. HD patients with depression symptoms have a higher occurrence of cognitive impairment and risk of hospitalization, lower quality life, and lower adherence with dietary and fluid restrictions and dialysis treatments [2, 3, 7–12], all of which may contribute to an increased risk of mortality. Second, greater depression symptoms may reflect existing comorbidity burden, and therefore confound the relationship between comorbid conditions and mortality. The converse can also be true, with depression resulting in more severe comorbidity, such as malnutrition due to anorexia, with these comorbidities confounding the relationship between depression and mortality. For example, in our analyses, history of cardiovascular disease substantially attenuates the relationship between CES-D score and outcomes, but determining which may be causal and which may be a confounder is not possible in an observational design. In exploratory analyses, we noted that there was no statistically significant interaction between baseline CES-D score and antidepressant medication use, but individuals with higher CES-D scores and receiving medications had the highest risk of mortality. One explanation for this result is indication bias, such that HD patients with more severe depression symptoms are more likely to be treated by antidepressant medication.

There are several strengths of our study. First, the relationship between depression symptoms and outcomes was evaluated using both baseline and time-dependent CES-D results. Second, we were able to incorporate data on use of medications targeting depression. Third, we had detailed ascertainment of other mortality risk factors and outcomes and are able to account for these in multivariable analyses. This study also has several limitations including the absence of gold standard for depression ascertainment. Importantly, the CES-D is a widely used instrument for depression screening and has been validated in the hemodialysis population [19]. Second, we did not capture longitudinal use of anti-depressant medication or medication dosage. Additionally, we are unable to account for indication bias, such that individuals with more symptoms of depression are more likely to receive antidepressant medications. Third, we have relatively few events when examining subgroups based on the constellation of medications and symptoms. Finally, given the observational nature of the cohort and the heterogeneity of depression symptoms, both residual confounding and unmeasured confounding are possible.

In conclusion, symptoms of depression are associated with an increased risk of mortality in maintenance hemodialysis patients, but this relationship was attenuated with adjustment for comorbid conditions, suggesting a complex relationship between depression and clinical conditions. Further studies are needed to evaluate whether treatment of depression with medications, cognitive behavioral therapy [24], or other techniques can impact morbidity and mortality among hemodialysis patients.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study was funded through the following grants: R21 DK068310 (MJS) and R01 DK078204 (MJS), UL1 TR000073 NIH CTSA, K24 DK078204, American Society of Nephrology Research Fellowship Grant (DAD). No authors have financial conflicts related to this manuscript. An abstract based on this manuscript was presented the 2013 American Society of Nephrology Kidney Week in Atlanta, GA. We would also like to acknowledge the tremendous assistance of Dialysis Clinic, Inc. and, in particular, the staff and patients at the five DCI units in the Boston area and St. Elizabeth’s Dialysis unit, whose generous cooperation made this study possible.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: None declared.

References

- 1.Palmer S, Vecchio M, Craig JC, et al. Prevalence of depression in chronic kidney disease: systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Kidney Int. 2013;84:179–191. doi: 10.1038/ki.2013.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hedayati SS, Bosworth HB, Briley LP, et al. Death or hospitalization of patients on chronic hemodialysis is associated with a physician-based diagnosis of depression. Kidney Int. 2008;74:930–936. doi: 10.1038/ki.2008.311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Riezebos RK, Nauta KJ, Honig A, Dekker FW, Siegert CE. The association of depressive symptoms with survival in a Dutch cohort of patients with end-stage renal disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2010;25:231–236. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfp383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mykletun A, Bjerkeset O, Overland S, et al. Levels of anxiety and depression as predictors of mortality: the HUNT study. Br J Psychiatry. 2009;195:118–125. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.108.054866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Patten SB, Williams JV, Lavorato D, et al. Mortality associated with major depression in a Canadian community cohort. Can J Psychiatry. 2011;56:658–666. doi: 10.1177/070674371105601104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Palmer SC, Vecchio M, Craig JC, et al. Association between depression and death in people with CKD: a meta-analysis of cohort studies. Am J Kidney Dis. 2013;62:493–505. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2013.02.369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tsay SL, Healstead M. Self-care self-efficacy, depression, and quality of life among patients receiving hemodialysis in Taiwan. Int J Nurs Stud. 2002;39:245–251. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7489(01)00030-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Watnick S, Kirwin P, Mahnensmith R, Concato J. The prevalence and treatment of depression among patients starting dialysis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2003;41:105–110. doi: 10.1053/ajkd.2003.50029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lopes AA, Bragg J, Young E, et al. Depression as a predictor of mortality and hospitalization among hemodialysis patients in the United States and Europe. Kidney Int. 2002;62:199–207. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2002.00411.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Agganis BT, Weiner DE, Giang LM, et al. Depression and cognitive function in maintenance hemodialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis. 2010;56:704–712. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2010.04.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chilcot J, Davenport A, Wellsted D, Firth J, Farrington K. An association between depressive symptoms and survival in incident dialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2011;26:1628–1634. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfq611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lacson E, Jr, Li NC, Guerra-Dean S, et al. Depressive symptoms associate with high mortality risk and dialysis withdrawal in incident hemodialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2012;27:2921–2928. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfr778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kimmel PL, Peterson RA, Weihs KL, et al. Multiple measurements of depression predict mortality in a longitudinal study of chronic hemodialysis outpatients. Kidney Int. 2000;57:2093–2098. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2000.00059.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boulware LE, Liu Y, Fink NE, et al. Temporal relation among depression symptoms, cardiovascular disease events, and mortality in end-stage renal disease: contribution of reverse causality. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;1:496–504. doi: 10.2215/CJN.00030505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.DiMatteo MR, Lepper HS, Croghan TW. Depression is a risk factor for noncompliance with medical treatment: meta-analysis of the effects of anxiety and depression on patient adherence. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:2101–2107. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.14.2101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cukor D, Rosenthal DS, Jindal RM, Brown CD, Kimmel PL. Depression is an important contributor to low medication adherence in hemodialyzed patients and transplant recipients. Kidney Int. 2009;75:1223–1229. doi: 10.1038/ki.2009.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lopes AA, Albert JM, Young EW, et al. Screening for depression in hemodialysis patients: associations with diagnosis, treatment, and outcomes in the DOPPS. Kidney Int. 2004;66:2047–2053. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2004.00977.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: A self report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurements. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hedayati SS, Bosworth HB, Kuchibhatla M, Kimmel PL, Szczech LA. The predictive value of self-report scales compared with physician diagnosis of depression in hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int. 2006;69:1662–1668. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5000308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) 2013 CMS Measures Inventory. http://wwwcmsgov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/QualityMeasures/CMS-Measures-Inventoryhtml.

- 21.K/DOQI clinical practice guidelines for cardiovascular disease in dialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis. 2005;45:S1–153. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hedayati SS, Yalamanchili V, Finkelstein FO. A practical approach to the treatment of depression in patients with chronic kidney disease and end-stage renal disease. Kidney Int. 2012;81:247–255. doi: 10.1038/ki.2011.358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Farrokhi F, Abedi N, Beyene J, Kurdyak P, Jassal SV. Association Between Depression and Mortality in Patients Receiving Long-term Dialysis: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2013 doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2013.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cukor D, Ver Halen N, Asher DR, et al. Psychosocial intervention improves depression, quality of life, and fluid adherence in hemodialysis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014;25:196–206. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2012111134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.