Abstract

Context

Delirium occurs in patients across a wide array of health care settings. The extent to which formal management guidelines exist or are adaptable to palliative care is unclear.

Objectives

This review aims to 1) source published delirium management guidelines with potential relevance to palliative care settings, 2) discuss the process of guideline development, 3) appraise their clinical utility, and 4) outline the processes of their implementation and evaluation and make recommendations for future guideline development.

Methods

We searched PubMed (1990–2013), Scopus, U.S. National Guideline Clearinghouse, Google, and relevant reference lists to identify published guidelines for the management of delirium. This was supplemented with multidisciplinary input from delirium researchers and other relevant stakeholders at an international delirium study planning meeting.

Results

There is a paucity of high-level evidence for pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions in the management of delirium in palliative care. However, multiple delirium guidelines for clinical practice have been developed, with recommendations derived from “expert opinion” for areas where research evidence is lacking. In addition to their potential benefits, limitations of clinical guidelines warrant consideration. Guidelines should be appraised and then adapted for use in a particular setting before implementation. Further research is needed on the evaluation of guidelines, as disseminated and implemented in a clinical setting, focusing on measurable outcomes in addition to their impact on quality of care.

Conclusion

Delirium clinical guidelines are available but the level of evidence is limited. More robust evidence is required for future guideline development.

Keywords: Delirium, palliative care, practice guidelines

Introduction

The evidence base for the management of delirium in palliative care patients is limited by the lack of good quality randomized controlled trials,1 with practice often guided by expert opinion and consensus-based clinical guidelines. Clinical practice guidelines have been defined as “systematically developed statements to assist practitioner and patient decisions about appropriate health care for specific clinical circumstances.”2 From the Canadian Medical Association’s Handbook on Clinical Practice Guidelines, guidelines aim to “summarize research findings and make clinical decisions more transparent” and “identify gaps in knowledge and prioritize research activities.”3 Considering delirium, these aims are especially advantageous, given the multifaceted approach required for delirium assessment and management. The development of guidelines requires a broad evidence-based approach to evaluate research findings4 but good quality studies are still lacking.

This review aims to 1) source published delirium management guidelines with potential relevance to palliative care settings, 2) discuss the process of guideline development, 3) appraise their clinical utility, and 4) outline the processes of their implementation and evaluation and make recommendations for future guideline development.

Methods

Various formal delirium clinical guidelines have been developed by consensus. Before an international delirium study meeting, a non-systematic search for formal guidelines wa conducted. We searched PubMed (1990–2013), Scopus, U.S. National Guideline Clearinghouse, Google™, and relevant reference lists to identify published guidelines for the management of delirium. “Relevance” was determined by the primary author’s (S. H. B.) review of titles and abstract or content, where available. The Scopus database was used because of its broader journal range.5 In June 2012, Scopus was searched using the search term “delirium guideline.” The National Guideline Clearinghouse, hosted by the U.S.-based Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality,6 was searched according to “guidelines by topic” and “delirium.” Google™ was searched using the search term “delirium guideline” and reviewing the first 15 Web pages of results. A PubMed search of “delirium,” using “guideline” and “English” as filters, was subsequently conducted in March 2013. This literature search was supplemented with multidisciplinary input from delirium researchers and other relevant stakeholders (primary care and specialist-level clinicians, palliative care experts, and clinical administrators) at a two-day international delirium study planning meeting (SUNDIPS) in June 2012 in Ottawa.

Results

Scope of Identified Delirium Guidelines

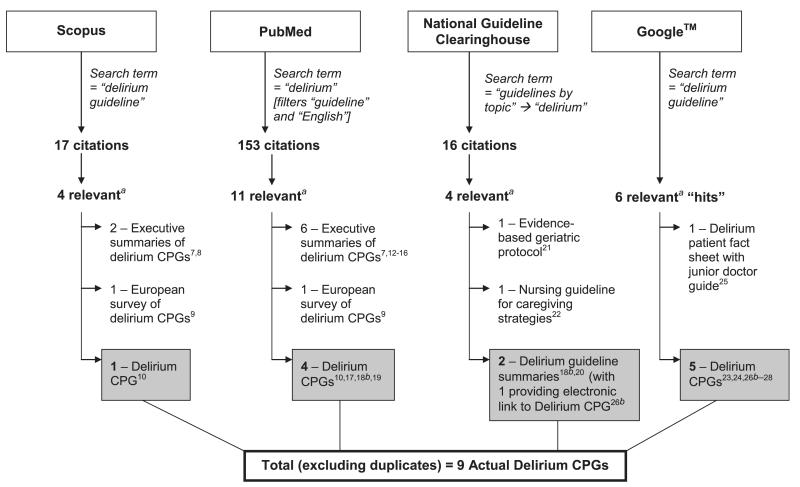

The Scopus database search resulted in 17 citations, of which four were relevant: two articles summarized delirium guidelines,7,8 one reported a European survey of delirium guidelines,9 and one presented delirium guidelines for general hospitals.10 A follow-up Scopus search, conducted in March 2013, retrieved another article describing a controlled trial evaluation of implemented delirium guidelines on a medical ward in Australia.11

The PubMed search retrieved 153 articles, of which 11 were relevant to the topic of delirium guidelines on abstract review. These included six published articles providing “executive summaries” of published guidelines7,12–16 and the same European survey of delirium guidelines.9 Only four distinct delirium guidelines were retrieved from the PubMed search: American Psychiatric Association (APA),17 the U.K. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE),18 guidelines for general hospitals,10 and the recently updated clinical practice guidelines for the intensive care setting.19

Sixteen listings were found on the National Guideline Clearinghouse Web site.6 From these, only a summary of the NICE guideline (with an electronic link to obtain a PDF version of the guideline), an “acute confusion/delirium” guideline summary,20 and an evidence-based geriatric nursing protocol21 specifically referred to delirium. Additionally, the summary for an updated version of nursing guidelines for caregiving strategies for older adults with delirium, dementia, and depression also was sourced on this repository.22

From the Google™ search, it was possible to find the repositories and retrieve a larger number of actual guidelines including those from the APA,23 Royal College of Physicians with the British Geriatric Society,24 Royal College of Psychiatrists (a fact sheet for patients and junior doctor’s practical guide),25 NICE,26 and Australian and Canadian (2006) delirium guidelines in the elderly.27,28 Excluding duplicates, the overall literature search sourced nine actual delirium guidelines; a summary of these results is shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Summary of results of non-systemic literature search for delirium guidelines. CPG = Clinical Practice Guideline. a“Relevance” determined by S. H. B.’s review of titles, abstract, and/or content. bNote: Reference 18 and 26 are different sources/citations for the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) CPG.

Review of the titles and tables of contents where appropriate (S. H. B.) of the sourced guidelines and executive summaries identified four published guidelines focusing on the management of delirium at the end of life, or in older adults.29–32 In addition, another earlier delirium guideline with a focus on patients near the end of life was sourced through separate hand searching (S. H. B.)33 (Table 1). The APA Practice Guideline for the treatment of patients with delirium was the earliest published guideline found.17 It was originally published in May 1999 but has not been formally updated since then.

Table 1.

Examples of Published Guidelines on the Management of Delirium at the End of Life and in Older Adults

| Guideline Title | Source | Country, Year | Domains Included |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diagnosis and Management of Delirium near the End of Life33 | American College of Physicians-American Society of Internal Medicine End-of-Life Care Consensus Panel | United States, 2001 | Detection, assessment, prevention and non-pharmacological management, pharmacological management |

| Guideline on the Assessment and Treatment of Delirium in Older Adults at the End of Life29 | Canadian Coalition for Seniors’ Mental Health | Canada, 2010 | Prevention, detection, assessment, monitoring, nonpharmacological management, pharmacological management, education, legal, and ethical issues |

| Prevention, Diagnosis, and Management of Delirium in Older People: National Guidelines30 | British Geriatric Society and Royal College of Physicians | United Kingdom, 2006 | Prevention, detection, assessment, nonpharmacological management, pharmacological management, education, implementation |

| Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Management of Delirium in Older People31 | Clinical Epidemiology and Health Service Evaluation Unit, Melbourne and Delirium Clinical Guidelines Expert Working Group | Australia, 2006 | Detection, assessment of risk factors, prevention, nonpharmacological management, pharmacological management, education, implications for research, implementation |

| National Guidelines for Senior Mental Health: The Assessment and Treatment of Delirium32 | Canadian Coalition for Seniors’ Mental Health | Canada, 2006 | Prevention, detection, assessment, monitoring, nonpharmacological management, pharmacological management, education, legal and ethical issues, systems of care, challenges and opportunities for research on delirium |

In 2006, Leentjens and Diefenbacher reported a survey of national liaison psychiatric associations to ascertain the existence and content of European delirium guidelines.9 At that time, only the associations for The Netherlands and Germany reported having national delirium guidelines, with the German guideline being focused on alcohol withdrawal delirium. Locally developed institutional guidelines also were reported, and beyond consultation-liaison psychiatric associations, the British Geriatric Society guideline was highlighted. The following year, Michaud et al. reported the development of delirium guidelines for general hospitals in Lausanne, Switzerland. An expert multidisciplinary panel used a consultative process to supplement the areas of low evidence found on evaluation of the literature and gain consensus on comprehensive recommendations.10 More recently, the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs published a systematic review of the evidence for the screening, prevention, and diagnosis of delirium.34

The degree of dissemination of delirium guidelines published by guideline development groups, colleges, specialist professional societies, and government organizations into the peer-reviewed literature from our literature search appeared to vary.7,8,12–15 NICE created a brief downloadable slide set for implementing its clinical guideline on delirium.35 An interactive case-based tutorial was developed for the 2006 Canadian Coalition for Seniors’ Mental Health National Guidelines.36

Discussion

The Process of Delirium Guideline Development

The development of clinical guidelines takes significant time and money.9,10 Guideline development panels should include various members of the interprofessional care team including nursing, as well as other clinical disciplines (e.g., psychiatry, geriatrics, pharmacists), nonclinical stakeholders (such as health economists and methodological experts), and carers/family members.9,37

There remains a lack of evidence for many interventions, so many delirium guideline recommendations may only be supported by weak or inconclusive evidence or derived from “expert opinion” within the guideline development group. Further studies with higher quality design and placebo-controlled trials are needed to strengthen recommendations related to specific interventions within guidelines, including pharmacological and non-pharmacological modalities and approaches.1,38 Defined methods for incorporating qualitative studies and other types of knowledge, such as clinical audits and quality improvement projects, into clinical guidelines need to be developed.39

The validity and quality of clinical practice guidelines should be critically assessed.40 Guideline quality is impacted by many factors, including lack of adherence to methodological standards for development, composition of the writing panel, potential conflicts of interest, limited external review,37,41 and not solely on the quality of currently available published studies. The Appraisal of Guidelines for Research and Evaluation (AGREE) instrument, now updated to AGREE II, is an example of an appraisal instrument to assess the quality of clinical practice guidelines and evaluates the development process.42,43 Clinical guidelines need to be kept up to date, the so called “living guideline.”3 To avoid guidelines going beyond an “expiry date,” it has been recommended that guideline validity is reassessed every three years.44 However, the National Guideline Clearinghouse Web site requires annual verification,6 and in April 2012, a summary of new evidence for the 2010 NICE clinical guideline was produced.45

Potential Benefits of Clinical Guidelines

Several potential benefits of guidelines have been noted, including benefits to patients through improved health outcomes on an individual level, along with shaping public policy at a macro level.46 For health care professionals, guidelines can assist with clinical care and decision making.46 By providing a standard of care and guidance to non-experts, guidelines ensure continuity of patient care and also reduce unnecessary variation in care delivery. Another potential benefit of guidelines is the ability to carry out benchmarking exercises for inter-institutional comparison and maintenance of predefined standards. However, guidelines lose their flexibility if automatically used as performance measures.47 By providing a critical appraisal of current research evidence, the process of guideline development will highlight the areas where more evidence and higher quality studies are needed.

Potential Limitations of Clinical Guidelines

Guidelines are not without limitations and these should be recognized. The recommendations may be influenced by the individual biases of members of the guideline development group, especially when research evidence is lacking. A flawed clinical guideline may compromise patient care by providing inaccurate or out-of-context information to clinicians.46 By standardizing clinical practice, guidelines may reduce individualized patient care if they are applied without inbuilt flexibility, as there may be individual patient situations that warrant deviation from practice guidelines. Guidelines may not be applicable across diverse populations. General delirium guidelines may not address specific issues relating to particular patient populations, such as palliative care. Poor accessibility, duplication, and suboptimal implementation of clinical guidelines may lead to guideline confusion or “fatigue” and lead to poor uptake and adoption by health care professionals. There may be legal implications for cases where health care professionals have deviated from clinical practice guidelines that have been accepted into routine practice if the guideline is considered to be a standard of care.48,49

Implementation of Clinical Guidelines

Shaneyfelt stresses that the goal of guidelines is to enhance health care quality and outcomes.37 However, circulation of guidelines alone may not achieve this, even when supplemented with teaching sessions.50 Potential barriers to change should be determined to assist with the planning of a site implementation initiative.51 These include barriers relating to the current level of knowledge, existing culture, and practices of health care professionals, in addition to organizational and economic barriers.3,52 The implementation of guidelines requires ongoing education, organizational change, management “buy in,” and budgetary support.9,38,53 Long-term organizational support is also critical to ensure sustainability.8,11 Appraised guidelines need to be adapted for use in a particular setting, taking into account current institutional culture and resource availability, by a multidisciplinary clinical practice guideline working group before commencing the implementation strategy.52 Several approaches have been described to adapt or adopt existing guidelines and improve utilization. These include the ADAPTE and CAN-IMPLEMENT methodologies.54–56 The guideline recommendations may need to be reconceived as measurable criteria and quality improvement goals.52 This will enable outcomes to be quantified post-implementation. The full version of a lengthy, but comprehensive, guideline is often impractical to implement in busy clinical settings, so it may need to be reformatted as a practical user-friendly summary sheet that is easy to follow. Adapted guidelines need to support staff, rather than add additional burden.57 A variety of dissemination techniques and implementation strategies that actively engage health care professionals should be considered.58 However, single interventions (such as dissemination of educational materials) may be as effective as multifaceted interventions59 but more evidence is required.60 Visible reminders such as posted flyers and also clinical prompts or algorithms will assist health professionals to use the guideline in their clinical practice.

Evaluation of Implemented Clinical Guidelines

A formal evaluation plan is vital to assessing the impact of clinical guidelines on the quality of patient care and other desired outcomes, as well as unintended consequences and undesirable outcomes. The support of guideline evaluation experts for this stage is recommended.3 Measurable evaluation outcomes should be determined by the clinical practice guideline working group. This will inform the necessary data collection strategy and the most appropriate study design.3

An Australian medical record audit of elderly hospitalized patients with delirium, before the implementation of new guidelines, showed a wide variation in prescribing of anti-psychotics and associated documentation.61 A lack of physician prescribing consistency can be very confusing, especially for nursing staff and medical learners, and affect quality of care. Guidelines should help clinicians follow a more integrated approach to manage delirium, thus reducing unnecessary variation in care delivery.12 The impact of guidelines on standardizing an institution’s pharmacological management of delirium in palliative care patients (choice of drugs and dosing) and improving documentation is an area deserving further study. This in turn will stimulate a search for further evidence regarding the appropriate drug dosing of antipsychotics in delirium management in this patient population. Leentjens and Diefenbacher pointed out that for a guideline to be truly “evidence based,” and not just developed from evidence-based studies, then it should be first tested against usual treatment.9

The efficacy of guidelines in the implementation of non-pharmacological interventions by nursing and other clinical staff for patients at risk or experiencing delirium is another area for further research in palliative care populations.62 The evidence used to make individual recommendations within a guideline are often based on the potential benefit or harm of a particular intervention, whereas the evaluation of an implemented guideline appraises the potential additive, synergistic, or antagonistic effects of a multifaceted approach to a disease or syndrome, such as delirium.

Other examples for future research evaluating guideline implementation may include local, single center initiatives that include the measurement of outcomes pre- and post-guideline implementation as a quality improvement project. The systematic assessment of the impact of implemented guidelines on clinical outcomes using standardized non-burdensome tools that are part of clinical practice could be a useful approach.63 Larger, multicentered research programs might evaluate adherence to implemented guideline recommendations and also clinical outcomes using a cluster randomized trial design involving multiple palliative care units and evaluating different guideline implementation strategies. Other quantitative and qualitative studies also are required for process evaluation, quality of care, and cost-effectiveness analysis.3,58,64–66 The evaluation of pharmacological delirium protocols and their impact on outcomes is another area for further research.38

Multidisciplinary Contributions at the SUNDIPS International Delirium Study Planning Meeting

With respect to delirium practice guidelines, participants’ opinions were divided into two groups. Even in the absence of a strong evidence base, many clinical guidelines have been developed but do not appear to have been embraced or taken up to guide health professional practice.47 Some participants advocated for the systematic implementation of adapted guidelines into clinical practice, notwithstanding the limitations in the levels of evidence. The impact of the guideline on patient and process outcomes would be systematically evaluated using standardized, validated, low-burden bedside instruments that assess pertinent outcomes such as the severity of delirium, agitation, and hallucinations and also show the effect on standardization of care among members of the palliative care community. Evaluation of implemented guidelines also enables the assessment of the difference in outcomes (effectiveness and harms) in the real world where prescribers are not bound by the constraints of the clinical trial environment. It also could include, for example, processes to systematically assess and document the impact of rescue doses of antipsychotic medications. In contrast, some participants felt that at this stage, given the ongoing relative lack of research evidence, current delirium guidelines should not be used as they are mainly expert consensus statements. Instead, research efforts should be focused on generating new high-level evidence first to strengthen the current evidence base for delirium practice. However, the limitation to this approach is that, given the challenges in conducting research in end-of-life populations, let alone in patients with cognitive deficits, we would have to wait for many years before being ready to develop delirium guidelines based entirely on high level (randomized placebo-controlled studies) evidence.

Next Steps in Advancing Delirium Guideline Use in Palliative Care

Our non-systematic literature search with selected databases demonstrated that delirium guidelines can be difficult to source. To source all potential guidelines, a formal, librarian-assisted, systematic search should be conducted, including the grey literature. There is an outstanding need for a formal critical assessment of the quality and validity of published delirium guidelines, using tools such as AGREE,42,43 by independent reviewers. This process will then enable the selection of a high-quality and applicable delirium guideline to be adapted and then implemented into a local palliative care clinical setting by the interprofessional team. We have begun this process in our institution (S. H. B., P. G. L. and J. L. P.).

Conclusion

Further trials are needed to increase the evidence base from which delirium guidelines are derived and thus ensure best practice guidance. After first generating a robust body of research evidence, high-quality guidelines can then be developed and implemented strategically to disseminate this evidence. Even in the interim absence of a robust evidence base, implementation of current guidelines into clinical practice may facilitate the standardization of care and improve on the current choice of drugs and dosing regimens as well as generate new research ideas. The efficacy of guidelines implemented in different palliative care settings and with different implementation strategies needs further evaluation.

Acknowledgments

There was no funding source or sponsorship for this article. Drs. S. H. B., P. G. L., and J. L. P. receive research awards from the Department of Medicine, University of Ottawa. Dr. E. B. is supported in part by National Institutes of Health grant numbers RO1 NR010162-01A1, RO1 CA122292-01, and RO1 CA124481-01, and in part by the M. D. Anderson Cancer Center support grant #CA 016672. Dr. D. H. J. D. is funded by the Wellcome Trust as a Research Training Fellow. Dr. B. G. is the recipient of the “Chercheur-Boursier” award, from the Fonds de la recherche du Québec, Sante (FRQS).

The authors acknowledge input from the participants (listed in the Foreword to this Section) at the SUNDIPS Meeting, Ottawa, June 2012. This meeting received administrative support from Bruyère Research Institute and funding support through a joint research grant to Dr. P. G. L. from the Gillin Family and Bruyère Foundation.

Footnotes

Disclosures The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Candy B, Jackson KC, Jones L, et al. Drug therapy for delirium in terminally ill adult patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012:CD004770. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004770.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Field M, Lohr KN. Clinical practice guidelines: Directions for a new program. National Academy Press; Washington, DC: 1990. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Davis D, Goldman J, Palda VA. Handbook on clinical practice guidelines. Canadian Medical Association; Ottawa: 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Connis RT, Nickinovich DG, Caplan RA, Arens JF. The development of evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Integrating medical science and practice. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2000;16:1003–1012. doi: 10.1017/s0266462300103071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Falagas ME, Pitsouni EI, Malietzis GA, Pappas G. Comparison of PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar: strengths and weaknesses. FASEB J. 2008;22:338–342. doi: 10.1096/fj.07-9492LSF. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.National Guideline Clearinghouse [Accessed March 23, 2013];U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Available from http://guideline.gov/

- 7.Tropea J, Slee JA, Brand CA, Gray L, Snell T. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of delirium in older people in Australia. Australas J Ageing. 2008;27:150–156. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-6612.2008.00301.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hogan D, Gage L, Bruto V, et al. National guidelines for seniors’ mental health: the assessment and treatment of delirium. Can Geriatr J. 2006;9:S42–S51. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leentjens AF, Diefenbacher A. A survey of delirium guidelines in Europe. J Psychosom Res. 2006;61:123–128. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2006.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Michaud L, Bula C, Berney A, et al. Delirium: guidelines for general hospitals. J Psychosom Res. 2007;62:371–383. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2006.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mudge AM, Maussen C, Duncan J, Denaro CP. Improving quality of delirium care in a general medical service with established interdisciplinary care: a controlled trial. Intern Med J. 2013;43:270–277. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-5994.2012.02840.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barr J, Fraser GL, Puntillo K, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of pain, agitation, and delirium in adult patients in the intensive care unit: executive summary. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2013;70:53–58. doi: 10.1093/ajhp/70.1.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.O’Mahony R, Murthy L, Akunne A, Young J. Synopsis of the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence guideline for prevention of delirium. Ann Intern Med. 2011;154:746–751. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-154-11-201106070-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brajtman S, Wright D, Hogan DB, et al. Developing guidelines on the assessment and treatment of delirium in older adults at the end of life. Can Geriatr J. 2011;14:40–50. doi: 10.5770/cgj.v14i2.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Young J, Murthy L, Westby M, Akunne A, O’Mahony R. Diagnosis, prevention, and management of delirium: summary of NICE guidance. BMJ. 2010;341:c3704. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c3704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Potter J, George J. The prevention, diagnosis and management of delirium in older people: concise guidelines. Clin Med. 2006;6:303–308. doi: 10.7861/clinmedicine.6-3-303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.American Psychiatric Association Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with delirium. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156:1–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.National Clinical Guideline Centre (U.K.) Delirium: diagnosis, prevention and management [Internet] Royal College of Physicians (U.K.); London: 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barr J, Fraser GL, Puntillo K, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of pain, agitation, and delirium in adult patients in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2013;41:263–306. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3182783b72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sendelbach S, Guthrie PF, Schoenfelder DP. Acute confusion/delirium. University of Iowa Gerontological Nursing Interventions Research Center, Research Translation and Dissemination Core; Iowa City: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tullman D, Mion L, Fletcher K, Foreman M. Delirium: prevention, early recognition, and treatment. In: Capezuit E, Zwicker D, Mezey M, Fulmer T, editors. Evidence-based geriatric nursing protocols for best practice. 3rd ed Springer Publishing Company; New York: 2008. pp. 111–125. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Registered Nurses’ Association of Ontario (RNAO) Caregiving strategies for older adults with delirium, dementia, and depression. Registered Nurses’ Association of Ontario; Toronto: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 23.American Psychiatric Association [Accessed May 7, 2013];Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with delirium. 2012 Available from http://www.psych.org/practice/clinical-practice-guidelines.

- 24.Royal College of Physicians and British Geriatrics Society [Accessed May 7, 2013];The prevention, diagnosis and management of delirium in older people: National guidelines. 2006 Available from http://www.bgs.org.uk/index. php/clinicalguides/170-clinguidedeliriumtreatment.

- 25.Royal College of Psychiatrists [Accessed March 23, 2013];Delirium. 2012 Available from http://www.rcpsych.ac.uk/expertadvice/problems/physicalillness/delirium.aspx.

- 26.National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) [Accessed April 25, 2013];Delirium: diagnosis, prevention and management, Clinical guidelines, CG103. 2010 Available from http://www.nice.org.uk/cg103.

- 27.Clinical Epidemiology and Health Service Evaluation Unit. Melbourne Health [Accessed May 7, 2013];Clinical practice guidelines for the management of delirium in older people. 2007 Available from http://www.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/delerium-guidelines.htm.

- 28.Canadian Coalition for Seniors’ Mental Health [Accessed May 7, 2013];National guidelines for seniors’ mental health: The assessment and treatment of delirium. 2006 Available from http://www.ccsmh.ca/en/natlGuidelines/delirium.cfm.

- 29.Canadian Coalition for Seniors’ Mental Health. Guideline on the assessment and treatment of delirium in older adults at the end of life. Adapted from the CCSMH National guidelines for seniors’ mental health . The assessment and treatment of delirium. CCSMH; Toronto: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Royal College of Physicians and British Geriatrics Society . The prevention, diagnosis and management of delirium in older people: National guidelines. Royal College of Physicians; Salisbury, UK: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Clinical Epidemiology and Health Service Evaluation Unit MH . Clinical practice guidelines for the management of delirium in older people. Victorian Government Department of Human Services; Melbourne, Victoria: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Canadian Coalition for Seniors’ Mental Health. National guidelines for seniors’ mental health . The assessment and treatment of delirium. CCSMH; Toronto: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Casarett DJ, Inouye SK. Diagnosis and management of delirium near the end of life. Ann Intern Med. 2001;135:32–40. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-135-1-200107030-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Greer N, Rossom R, Anderson P, et al. Delirium: Screening, prevention, and diagnosis—A systematic review of the evidence. Department of Veterans Affairs; Washington, DC: 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence [Accessed April 25, 2013];CG103 Delirium: Slide set. 2010 Available from http://guidance.nice.org.uk/CG103/SlideSet/ppt/English.

- 36.Canadian Coalition for Seniors’ Mental Health [Accessed April 25, 2013];Delirium in the elderly: CCSMH national guidelines-informed interactive case-based tutorial. 2008 Available from http://www.ccsmh.ca/en/resources/resources.cfm.

- 37.Shaneyfelt T. In guidelines we cannot trust: comment on “Failure of clinical practice guidelines to meet institute of medicine standards”. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172:1633–1634. doi: 10.1001/2013.jamainternmed.335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.O’Hanlon S, O’Regan N, Maclullich AM, et al. Improving delirium care through early intervention: from bench to bedside to boardroom. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2014;85:207–213. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2012-304334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zuiderent-Jerak T, Forland F, Macbeth F. Guidelines should reflect all knowledge, not just clinical trials. BMJ. 2012;345:e6702. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e6702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chou R. Using evidence in pain practice: Part I: assessing quality of systematic reviews and clinical practice guidelines. Pain Med. 2008;9:518–530. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2008.00422_1.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kung J, Miller RR, Mackowiak PA. Failure of clinical practice guidelines to meet Institute of Medicine standards: two more decades of little, if any, progress. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172:1628–1633. doi: 10.1001/2013.jamainternmed.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.AGREE Collaboration Development and validation of an international appraisal instrument for assessing the quality of clinical practice guidelines: the AGREE project. Qual Saf Health Care. 2003;12:18–23. doi: 10.1136/qhc.12.1.18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.National Collaborating Centre for Methods and Tools [Accessed April 25, 2013];Critically appraising practice guidelines: The AGREE II instrument. 2011 Available from http://www.nccmt.ca/registry/view/eng/100.html.

- 44.Shekelle PG, Ortiz E, Rhodes S, et al. Validity of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality clinical practice guidelines: how quickly do guidelines become outdated? JAMA. 2001;286:1461–1467. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.12.1461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) [Accessed May 7, 2013];Delirium: Evidence update April 2012. A summary of selected new evidence relevant to NICE clinical guideline 103 “Delirium: Diagnosis, prevention and management.”. 2012 Available from http://www.evidence.nhs.uk/topic/delirium. [PubMed]

- 46.Woolf SH, Grol R, Hutchinson A, Eccles M, Grimshaw J. Clinical guidelines: potential benefits, limitations, and harms of clinical guidelines. BMJ. 1999;318:527–530. doi: 10.1136/bmj.318.7182.527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shaneyfelt TM, Centor RM. Reassessment of clinical practice guidelines: go gently into that good night. JAMA. 2009;301:868–869. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jutras D. Clinical practice guidelines as legal norms. CMAJ. 1993;148:905–908. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Anonymous Clinical practice guidelines: what is their role in legal proceedings? CMPA Perspective. 2011:3–5. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Young LJ, George J. Do guidelines improve the process and outcomes of care in delirium? Age Ageing. 2003;32:525–528. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afg094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Baker R, Camosso-Stefinovic J, Gillies C, et al. Tailored interventions to overcome identified barriers to change: effects on professional practice and health care outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010:CD005470. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005470.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Feder G, Eccles M, Grol R, Griffiths C, Grimshaw J. Clinical guidelines: using clinical guidelines. BMJ. 1999;318:728–730. doi: 10.1136/bmj.318.7185.728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Grimshaw JM, Thomas RE, MacLennan G, et al. Effectiveness and efficiency of guideline dissemination and implementation strategies. Health Technol Assess. 2004;8:iii–72. doi: 10.3310/hta8060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fervers B, Burgers JS, Voellinger R, et al. Guideline adaptation: an approach to enhance efficiency in guideline development and improve utilisation. BMJ Qual Saf. 2011;20:228–236. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs.2010.043257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.ADAPTE [Accessed April 25, 2013];Guideline adaptation: An approach to enhance efficiency in guideline development and improve utilisation. 2007 doi: 10.1136/bmjqs.2010.043257. Available from http://www.adapte.org/www/ [DOI] [PubMed]

- 56.The Canadian Partnership Against Cancer [Accessed May 7, 2013];CAN-IMPLEMENT: Guideline adaptations. 2013 Available from http://www.cancerview.ca.

- 57.Carthey J, Walker S, Deelchand V, Vincent C, Griffiths WH. Breaking the rules: understanding non-compliance with policies and guidelines. BMJ. 2011;343:d5283. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d5283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Prior M, Guerin M, Grimmer-Somers K. The effectiveness of clinical guideline implementation strategies—a synthesis of systematic review findings. J Eval Clin Pract. 2008;14:888–897. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2008.01014.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Grimshaw J, Eccles M, Thomas R, et al. Toward evidence-based quality improvement. Evidence (and its limitations) of the effectiveness of guideline dissemination and implementation strategies 1966-1998. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:S14–S20. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00357.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Giguere A, Legare F, Grimshaw J, et al. Printed educational materials: effects on professional practice and healthcare outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012:CD004398. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004398.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tropea J, Slee J, Holmes AC, Gorelik A, Brand CA. Use of antipsychotic medications for the management of delirium: an audit of current practice in the acute care setting. Int Psychogeriatr. 2009;21:172–179. doi: 10.1017/S1041610208008028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yevchak A, Steis M, Diehl T, et al. Managing delirium in the acute care setting: a pilot focus group study. Int J Older People Nurs. 2012;7:152–162. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-3743.2012.00324.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bruera E, Seifert L, Watanabe S, et al. Chronic nausea in advanced cancer patients: a retrospective assessment of a metoclopramide-based antiemetic regimen. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1996;11:147–153. doi: 10.1016/0885-3924(95)00161-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Mehta RH, Montoye CK, Gallogly M, et al. Improving quality of care for acute myocardial infarction: the Guidelines Applied in Practice (GAP) Initiative. JAMA. 2002;287:1269–1276. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.10.1269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Fretheim A, Oxman AD, Havelsrud K, et al. Rational prescribing in primary care (RaPP): a cluster randomized trial of a tailored intervention. PLoS Med. 2006;3:e134. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Davies B, Edwards N, Ploeg J, Virani T. Insights about the process and impact of implementing nursing guidelines on delivery of care in hospitals and community settings. BMC Health Serv Res. 2008;8:29. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-8-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]