Abstract

Introduction/Purpose

Childhood cancer survivors (CCS) experience late effects that interfere with physical function. Limitations in physical function can impact CCS abilities to actively participate in daily activities. The purpose of this investigation was to evaluate the concordance between self-reported physical performance and clinically evaluated physical performance among adult CCS.

Methods

CCS 18+ years of age and 10+ years from diagnosis who are participants in the St. Jude Lifetime Cohort study responded to the physical function section of the Medical Outcome Survey Short Form (SF36). Measured physical performance was evaluated with the physical performance test (PPT), and the six minute walk test (6MW).

Results

1778 individuals (50.8% female) with a median time since diagnosis of 24.9 years (range 10.9-48.2) and a median age of 32.4 years (range 19.1-48.2) completed testing. Limitations in physical performance were self-reported by 14.1% of participants. The accuracy of self-report physical performance was 0.87 when the SF-36 was compared to the 6MW or PPT. Reporting inaccuracies most often involved reporting a physical performance limitation. Poor accuracy was associated with previous diagnosis of a bone or central nervous system tumor, lymphoma, older age, and large body size.

Conclusion

These results suggest that self-report, using the physical performance sub-scale of the SF-36 correctly identifies CCS who do not have physical performance limitations. In contrast, this same measure is less able to identify individuals who have performance limitations.

Keywords: Self-report, physical function, childhood cancer, physical performance limitation, cancer survivorship

Introduction

Paragraph Number 1 Survival rates following a diagnosis of childhood cancer have increased dramatically over the past four decades (30). This increase has resulted in an estimated 366,000 survivors of childhood cancer living in the United States (14). An expanding body of literature demonstrates that cancer treatment, which may consist of some combination of surgery, chemotherapy or radiotherapy, can have long term and damaging effects on growing children (2). Chronic health conditions are prevalent in over 70% of survivors 30 years from cancer diagnosis and can include subsequent neoplasms, cardiopulmonary dysfunction, metabolic abnormalities, neuroendocrine disorders, neurocognitive disability, neurological or sensory impairment and musculoskeletal disability(24).

Paragraph Number 2 Previous literature suggests that these late effects make cancer survivors at least five times more likely to have functional impairments and twice as likely to have activity limitations than siblings (22). The compound effects of treatment-related impairments and inactivity during and post cancer treatment contribute to muscle atrophy, cardiorespiratory deterioration, bone loss and diminished physical performance abilities (34). These impairments and limitations have the potential to negatively impact survivors' abilities not only for leisure time physical activities, but also for social recreation that requires a certain degree of community mobility (23). At the extreme, significant loss of physical performance may even interfere with simple tasks required for daily living, like bathing, dressing and meal preparation.

Paragraph Number 3 Prevalence estimates for physical performance limitations among cancer survivors range from 9.5% to 19.6% (21, 33). This variation is likely because different methods of assessment may affect the accuracy of physical disability estimates (16, 36). Several studies suggest that questionnaires, either self-reported or interviewer administered, tend to underestimate physical disability when compared to clinical evaluation (13, 32). These discrepancies make documenting the burden of physical disability difficult. It is important to be able to accurately identify CCS with clinically ascertained physical disability as these are the individuals who are most likely to benefit from intervention to remediate functional loss. With this in mind, the primary aim of this investigation was to evaluate the accuracy of self-reported physical performance limitations in childhood cancer survivors.

Material and Methods

Study population

Paragraph Number 4 Participants were members of the St. Jude Lifetime cohort (SJLIFE), a study of adult survivors of pediatric cancer treated at St. Jude Children's Research Hospital (SJCRH). The primary aim of SJLIFE is to evaluate health outcomes among childhood cancer survivors as they age. Participants had a previous diagnosis of a childhood malignancy treated at SJCRH, were 18 years of age or older, at least ten years from diagnosis, and were willing to return to SJCRH for evaluation. These analyses include survivors who completed an initial medical follow-up visit and functional assessment between November 2007 and April 2012. All procedures were approved by the SJCRH Institutional Review Board. Written informed consent was obtained for each study participant prior to testing.

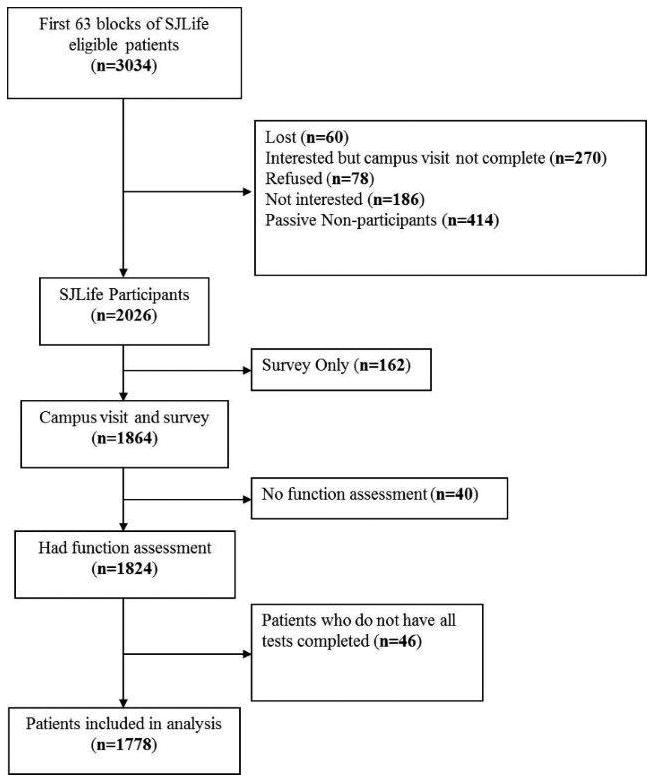

Paragraph Number 5 Among the 4263 potentially eligible members of the SJLIFE cohort, 4129 had been invited to participate as of April 30, 2012. In the first 63 blocks, 3034 patients were eligible for our study. Non-participants included 678 who actively or passively declined participation, 60 who were lost to follow-up and 270 who agreed to participate, but who had not yet been scheduled for their visit, 162 who agreed to complete a survey, but not to return for a medical evaluation, 40 who completed a medical evaluation, but not a functional assessment (Figure 1). Our analysis includes 1778 participants, 58.6% of those eligible.

Figure 1. Consort diagram as of April 30, 2012.

Population characteristics

Paragraph Number 6 Demographic and cancer treatment data were obtained from medical records by trained abstractors. All abstractions were reviewed and approved by a physician. Height and weight were measured without shoes using a wall mounted stadiometer and an electronic scale, respectively. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated by dividing weight in kilograms (kg) by height in meters squared (m2).

Self-reported physical performance limitation

Paragraph Number 7 As part of their SJLIFE evaluation, participants completed a battery of health questionnaires, one of which includes the 10-item physical functioning subscale of the Medical Outcomes Study Short Form 36 (SF-36) (3, 38). The SF-36 is a widely used generic health related quality of life questionnaire that has been tested in multiple populations, including cancer survivors (29, 39). It is valid (r=0.40) and reliable (Cronbach alpha 0.82 to 0.90) (26, 29, 37, 39) and takes 5 to 10 minutes to complete. Raw scores were summed for each 10 items on the physical functioning subscale and converted into T-scores with a population mean of 50 and a standard deviation of 10 (37, 39). As in previous analysis, we classified individuals with T-scores of ≤37 on the physical function subscale as having self-reported physical performance limitations (28). This corresponds to the lowest 10th percentile of the general population (3, 37, 39).

Clinical assessment of physical performance limitations

Paragraph Number 8 Two clinical measures were used to categorize physical performance limitations. During a comprehensive functional assessment, study participants completed the Physical Performance Test (PPT) and the Six Minute Walk test (6MW). The seven item PPT, originally described by Reuben and Siu,(27) is an assessment of the time it takes to complete each of a series of tasks typically performed during activities of daily living. It has been used in geriatric patient populations to identify mild to moderate frailty and to predict risk for falls (5). Scores on the PPT are inversely correlated with degree of disability, loss of independence and early mortality (5, 8). Scores on the PPT range from 0-28. Patients were observed and timed as they 1) wrote a brief sentence, 2) simulated eating, 3) lifted a book and put it on a shelf, 4) put on and removed a jacket, 5) picked up a penny, 6) walked 50 ft., and 7) turned around in place. Participants with PPT scores ≤ 17 were classified as having a clinically identified physical performance limitation. A cut point of ≤17 corresponds to being unlikely to function in the community independently (12). The 6MW test is a general measure of physical fitness. Researchers have used the test to evaluate cardiorespiratory fitness in specific populations including those with respiratory disease (6), cystic fibrosis (11), and cancer (17). Healthy reference populations have been evaluated and provide normative data for comparison (9, 15). Participants were asked to walk indoors on a level surface for six minutes. They were instructed to walk as quickly as possible without running; standardized encouragement was provided each minute. Heart rate was monitored continuously with a polar heart rate (RS100; Lake Success, NY), and recorded along with a rating of perceived exertion (Borg scale) before beginning the test, at two minute intervals throughout the test, and following a two minute recovery period. Total distance walked was recorded in meters. Participants who walked distances ≤ 300 meters were classified as having a clinically identified physical performance limitation. The cut point of ≤300 meters corresponds to an aerobic capacity equivalent to moderate housework (i.e. sweeping floors or carrying groceries) (7, 31, 40).

Statistical analysis

Paragraph Number 9 Descriptive statistics were used to characterize the study population and the distribution of scores on the SF-36 physical function subscale, the PPT and the 6MW test. Demographic and treatment variables were compared between participants and non-participants with two-sample t-tests, non-parametric equivalents or chi-squared statistics (or fisher's exact tests) as appropriate. Statistical diagnostic tests (sensitivity or the proportion of positives correctly identified; specificity or the proportion of negatives correctly identified; accuracy or the proportion of positives and negatives correctly identified; and Cohen's kappa coefficient or inter-rater agreement) (1, 35) were used to evaluate the diagnostic accuracy of, and agreement between, self-reported physical performance limitations when each clinical assessment of physical performance was used as the “gold” standard. Logistic regression models were used to identify survivors who were most likely to report a limitation when one was not clinically apparent (“false positives”) after adjusting for gender, age, diagnosis, obesity status, and time since diagnosis. SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary NC) was used for all analyses.

Results

Study participants

Paragraph Number 10 The demographic and treatment characteristics of the 1778 participants are shown in Table 1. Slightly more than half of the survivors were female (50.8%), and leukemia comprised the most common childhood malignancy (45.3%). The median age at diagnosis was 6.8 (range 0-24.8) years and the median time since diagnosis was 24.9 (10.9-48.2) years. Overweight and obesity were present among 29.0% and 36.3% of survivors, respectively. Participants did not differ from non-participants by primary diagnosis or age at diagnosis, but were more likely to be female (p<0.01).

Table 1. Demographic Data.

| Participants | Non-participants | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| N=1778 | % | N=1256 | % | |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 875 | 49.2 | 708 | 56.4 |

| Female | 903 | 50.8 | 548 | 43.6 |

| Diagnosis | ||||

| Leukemia1 | 805 | 45.3 | 510 | 40.6 |

| Lymphoma | 321 | 18.1 | 228 | 18.1 |

| Bone tumor 2 | 128 | 7.2 | 88 | 7.0 |

| CNS tumorˆ | 141 | 7.9 | 110 | 8.8 |

| Other3 | 383 | 21.5 | 320 | 25.5 |

| Age at Diagnosis (Years) | ||||

| 0-4 | 696 | 39.2 | 480 | 38.2 |

| 5-9 | 434 | 24.4 | 320 | 25.5 |

| 10-14 | 380 | 21.4 | 268 | 21.3 |

| ≥15 | 268 | 15.1 | 188 | 15.0 |

| Age at Study (Years) | ||||

| 18-29 | 660 | 37.1 | - | - |

| 30-39 | 726 | 40.8 | - | - |

| 40-49 | 334 | 18.8 | - | - |

| 50-60 | 58 | 3.3 | - | - |

| Time Since Diagnosis (Years) | ||||

| 10-19 | 466 | 26.2 | - | - |

| 20-29 | 813 | 45.7 | - | - |

| 30-39 | 437 | 24.6 | - | - |

| 40-48 | 62 | 3.5 | - | - |

| BMI* (kg/m2) | ||||

| <18.5 | 64 | 3.6 | - | - |

| 18.5-24.9 | 553 | 31.1 | - | - |

| 25.0-29.9 | 515 | 29.0 | - | - |

| 30.0-34.9 | 339 | 19.1 | - | - |

| 35.0-39.9 | 164 | 9.2 | - | - |

| ≥40 | 143 | 8.0 | - | - |

Acute lymphoblastic leukemia, chronic myeloid leukemia acute myeloid leukemia, other leukemia

Ewing sarcoma, osteosarcoma

Carcinoma, germ cell tumor, hepatoblastoma, melanoma, Wilms tumor, retinoblastoma, neuroblastoma, rhabdomyosarcoma, soft tissue sarcoma, other malignancy

Central nervous system tumor

BMI=Body mass index, kg/m2=kilograms per meter squared

Physical performance

Paragraph Number 11 The mean scores on the SF-36 physical function scale and the physical performance test, and the mean distance walked in six minutes are shown in (see Table, SDC 1, Reported and measured physical function scores) by sex, diagnosis group, age at diagnosis, age at evaluation, time since diagnosis and body mass index. Males walked farther than females on the 6 MW test, but scored similarly on the SF-36 and PPT. Individuals with either a bone or central nervous system (CNS) tumor had the lowest scores on the physical function subscale of the SF-36, the physical performance test, and walked the shortest distances during the 6MW test. Age at diagnosis was associated with scores on the SF-36 physical function subscale. Older study participants scored lower on the SF-36 physical function subscale, physical performance test and walked shorter distances during the 6MW test. A BMI of ≥ 40 kg/m2 was associated with a lower score on the physical function subscale of the SF-36. A BMI of ≤ 18.5 kg/m2 or ≥35 kg/m2 was associated with lower physical performance test scores. Similarly a BMI of ≥35 kg/m2 was also associated with shorter walking distances during the 6 MW test.

Paragraph Number 12 The percentages of individuals classified with physical performance limitations according to the selected cut points for each measure are shown in Table 2. The percentage of individuals who self-reported physical performance limitations was highest among survivors treated for CNS tumors (22.0%), bone tumors (18.8%), or lymphoma (18.1%). Survivors older than age 50 years (34.5%), who had survived longer than 40 years (32.3%) or who had BMI values < 18.5 kg/m2 (20.3%) or >40 kg/m2 (25.2%) were also most likely to report physical performance limitations. Physical performance limitations assessed with the PPT were most prevalent among CNS tumor survivors (12.8%), individuals who had survived ≥40 years from diagnosis (11.3%) and in individuals with BMIs < 18.5 kg/m2 (10.9%). Physical performance limitations, assessed with the 6MW test were most prevalent in bone and CNS tumor survivors (15.6% and 9.2%), survivors older than age 50 years (13.8%) and among survivors whose BMI was <18.5 kg/m2 (12.5%) or >40 kg/m2 (11.2%).

Table 2. Poor reported and Measured Physical Function Scores.

| N=1778 | N | SF-36: PF (<=37) |

PPT (<= 17) |

6MW (<= 300) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | P-value** | N | % | P-value** | N | % | P-value** | ||||

| Sex | |||||||||||

| Male | 875 | 113 | 12.9 | Ref | 24 | 2.7 | Ref | 52 | 5.9 | Ref | |

| Female | 903 | 138 | 15.3 | 0.15 | 25 | 2.8 | 0.97 | 59 | 6.5 | 0.61 | |

| Diagnosis | |||||||||||

| Leukemia1 | 805 | 90 | 11.2 | Ref | 15 | 1.9 | Ref | 37 | 4.6 | Ref | |

| Lymphoma | 321 | 58 | 18.1 | 0.002 | 4 | 1.3 | 0.47 | 20 | 6.2 | 0.26 | |

| Bone Cancers 2 | 128 | 24 | 18.8 | 0.02 | 3 | 2.3 | 0.73 | 20 | 15.6 | <0.001 | |

| CNS tumorˆ | 141 | 31 | 22.0 | <0.001 | 18 | 12.8 | <0.001 | 13 | 9.2 | 0.02 | |

| Other3 | 383 | 48 | 12.5 | 0.50 | 9 | 2.4 | 0.58 | 21 | 5.5 | 0.51 | |

| Age at Diagnosis (Years) | |||||||||||

| 0-4 | 696 | 87 | 12.5 | Ref | 26 | 3.7 | Ref | 44 | 6.3 | Ref | |

| 5-9 | 434 | 53 | 12.2 | 0.89 | 12 | 2.8 | 0.38 | 21 | 4.8 | 0.30 | |

| 10-14 | 380 | 63 | 16.6 | 0.06 | 6 | 1.6 | 0.05 | 27 | 7.1 | 0.62 | |

| ≥15 | 268 | 48 | 17.9 | 0.03 | 5 | 1.9 | 0.14 | 19 | 7.1 | 0.67 | |

| Age at Study (Years) | |||||||||||

| 18-29 | 660 | 64 | 9.7 | Ref | 22 | 3.3 | Ref | 33 | 5.0 | Ref | |

| 30-39 | 726 | 100 | 13.8 | 0.02 | 14 | 1.9 | 0.10 | 46 | 6.3 | 0.28 | |

| 40-49 | 334 | 67 | 20.1 | <0.001 | 10 | 3.0 | 0.77 | 24 | 7.2 | 0.16 | |

| 50-60 | 58 | 20 | 34.5 | <0.001 | 3 | 5.2 | 0.46 | 8 | 13.8 | 0.01 | |

| Years Since Diagnosis (Years) | |||||||||||

| 10-19 | 466 | 44 | 9.4 | Ref | 10 | 2.2 | Ref | 19 | 4.1 | Ref | |

| 20-29 | 813 | 110 | 13.5 | 0.03 | 22 | 2.7 | 0.54 | 51 | 6.3 | 0.10 | |

| 30-39 | 437 | 77 | 17.6 | 0.001 | 10 | 2.3 | 0.88 | 33 | 7.6 | 0.03 | |

| 40-48 | 62 | 20 | 32.3 | <0.001 | 7 | 11.3 | 0.002 | 8 | 12.9 | 0.01 | |

| BMI* (kg/m2) | |||||||||||

| <18.5 | 64 | 13 | 20.3 | Ref | 7 | 10.9 | Ref | 8 | 12.5 | Ref | |

| 18.5-24.9 | 553 | 67 | 12.1 | 0.06 | 14 | 2.5 | 0.003 | 26 | 4.7 | 0.02 | |

| 25.0-29.9 | 515 | 56 | 10.9 | 0.03 | 9 | 1.8 | <0.001 | 29 | 5.6 | 0.03 | |

| 30.0-34.9 | 339 | 51 | 15.0 | 0.29 | 7 | 2.1 | 0.003 | 21 | 6.2 | 0.11 | |

| 35.0-39.9 | 164 | 28 | 17.1 | 0.57 | 6 | 3.7 | 0.05 | 11 | 6.7 | 0.16 | |

| >40 | 143 | 36 | 25.2 | 0.45 | 6 | 4.2 | 0.12 | 16 | 11.2 | 0.79 | |

Acute lymphoblastic leukemia, chronic myeloid leukemia acute myeloid leukemia, other leukemia

Ewing sarcoma, osteosarcoma

Carcinoma, germ cell tumor, hepatoblastoma, melanoma, Wilms tumor, retinoblastoma, neuroblastoma, rhabdomyosarcoma, soft tissue sarcoma, other malignancy

Central nervous system tumor

BMI=Body mass index, kg/m2=kilograms per meter squared

From Chi-Squared statistics or Fisher's Exact Test

Sensitivity, Specificity, and Accuracy

Paragraph Number 13 The overall sensitivities and specificities of self-reported physical performance limitations when compared to physical performance limitations measured and classified according to the two clinical assessments were 0.59 and 0.89 for the 6MW and 0.69 and 0.87 for the PPT, respectively (Table 3). When self-reported physical function was compared to 6MW or PPT, 13% of participants in this cohort were misclassified (Table 4). The positive predictive values for the 6MW (26%) and the PPT (14%) indicate that using the physical function subscale of the SF-36 with a cut point of 37 overestimates the prevalence of physical performance limitations when the clinical measures are considered the “gold standard”. The strength of the kappa coefficients in overall comparisons showed only fair or slight agreement between the SF-36 physical function subscale and the 6MW test (0.30; 95% CI 0.23-0.36) or PPT (0.19; 95% CI 0.13-0.25).

Table 3. Measured versus Self-Reported Physical Function.

| SF-36 (Physical Function) versus Six minute walk | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reported function | Measure function | Sensitivity1 | Specificity1 | Accuracy | + Predictive Value | Kappa (95% CI) |

||

| Poor | Good | |||||||

| Overall | Poor | 65 | 186 | 0.59 | 0.89 | 0.87 | 0.26 | 0.30 (0.23-0.36) |

| Good | 46 | 1481 | ||||||

| Females | Poor | 34 | 104 | 0.58 | 0.88 | 0.86 | 0.25 | 0.28 (0.19-0.37) |

| Good | 25 | 740 | ||||||

| Males | Poor | 31 | 82 | 0.60 | 0.90 | 0.88 | 0.27 | 0.32 (0.22-0.42) |

| Good | 21 | 741 | ||||||

| Bone Cancer | Poor | 11 | 13 | 0.55 | 0.88 | 0.83 | 0.46 | 0.40 (0.19-0.60) |

| Good | 9 | 95 | ||||||

| CNS tumorˆ | Poor | 11 | 20 | 0.85 | 0.84 | 0.84 | 0.35 | 0.43 (0.24-0.61) |

| Good | 2 | 108 | ||||||

| Leukemia | Poor | 17 | 73 | 0.46 | 0.90 | 0.88 | 0.19 | 0.22 (0.11-0.32) |

| Good | 20 | 695 | ||||||

| Lymphoma | Poor | 10 | 48 | 0.50 | 0.84 | 0.82 | 0.17 | 0.18 (0.05-0.31) |

| Good | 10 | 253 | ||||||

| Other Cancer | Poor | 16 | 32 | 0.76 | 0.91 | 0.90 | 0.33 | 0.42 (0.27-0.57) |

| Good | 5 | 330 | ||||||

|

| ||||||||

| SF-36 (Physical Function) versus PPT | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Overall | Poor | 34 | 217 | 0.69 | 0.87 | 0.87 | 0.14 | 0.19 (0.13-0.25) |

| Good | 15 | 1512 | ||||||

| Females | Poor | 19 | 119 | 0.76 | 0.86 | 0.86 | 0.14 | 0.20 (0.11-0.28) |

| Good | 6 | 759 | ||||||

| Males | Poor | 15 | 98 | 0.63 | 0.88 | 0.88 | 0.13 | 0.18 (0.09-0.27) |

| Good | 9 | 753 | ||||||

| Bone Cancer | Poor | 2 | 22 | 0.67 | 0.82 | 0.80 | 0.08 | 0.11 (-0.05-0.27) |

| Good | 1 | 103 | ||||||

| CNS tumorˆ | Poor | 12 | 19 | 0.67 | 0.85 | 0.82 | 0.39 | 0.39 (0.20-0.58) |

| Good | 6 | 104 | ||||||

| Leukemia | Poor | 12 | 78 | 0.80 | 0.90 | 0.90 | 0.13 | 0.20 (0.10-0.30) |

| Good | 3 | 712 | ||||||

| Lymphoma | Poor | 3 | 55 | 0.75 | 0.83 | 0.83 | 0.05 | 0.08 (-0.01-0.16) |

| Good | 1 | 262 | ||||||

| Other Cancer | Poor | 5 | 43 | 0.56 | 0.89 | 0.88 | 0.10 | 0.14 (0.01-0.27) |

| Good | 4 | 331 | ||||||

Sensitivity and specificity assume the PPT and 6MW are gold standard.

Central nervous system tumor

Table 4. Description of those misclassified.

| PPT (<= 17): Gold standard | 6MW (<= 300): Gold standard | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| False Positive | False Negative | False Positive | False Negative | ||||||

|

| |||||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| Overall | 1778 | 217 | 12.2 | 15 | 0.8 | 186 | 10.5 | 46 | 2.5 |

| Gender | |||||||||

| Male | 875 | 98 | 11.2 | 9 | 1.0 | 82 | 9.4 | 21 | 2.4 |

| Female | 903 | 119 | 13.2 | 6 | 0.7 | 104 | 11.5 | 25 | 2.8 |

| Diagnosis | |||||||||

| Leukemia1 | 805 | 78 | 9.7 | 3 | 0.4 | 73 | 9.1 | 20 | 2.5 |

| Lymphoma | 321 | 55 | 17.1 | 1 | 0.3 | 48 | 15.0 | 10 | 3.1 |

| Bone Cancers 2 | 128 | 22 | 17.2 | 1 | 0.8 | 13 | 10.2 | 9 | 7.0 |

| CNS tumorˆ | 141 | 19 | 13.5 | 6 | 4.3 | 20 | 14.2 | 2 | 1.4 |

| Other3 | 383 | 43 | 11.2 | 4 | 1.0 | 32 | 8.4 | 5 | 1.3 |

| Age at Diagnosis (Years) | |||||||||

| 0-4 | 696 | 60 | 8.6 | 9 | 1.3 | 50 | 7.2 | 12 | 1.7 |

| 5-9 | 434 | 55 | 12.7 | 4 | 0.9 | 51 | 11.8 | 14 | 3.2 |

| 10-14 | 380 | 57 | 15.0 | - | - | 48 | 12.6 | 12 | 3.2 |

| ≥15 | 268 | 45 | 16.8 | 2 | 0.7 | 37 | 13.8 | 8 | 3.0 |

| Age at Study (Years) | |||||||||

| 18-29 | 660 | 49 | 7.4 | 7 | 1.1 | 45 | 6.8 | 14 | 2.1 |

| 30-39 | 726 | 91 | 12.5 | 5 | 0.7 | 74 | 10.2 | 20 | 2.8 |

| 40-49 | 334 | 59 | 17.7 | 2 | 0.6 | 52 | 15.6 | 9 | 2.7 |

| 50-60 | 58 | 18 | 31.0 | 1 | 1.7 | 15 | 25.9 | 3 | 5.2 |

| Years Since Diagnosis (Years) | |||||||||

| 10-19 | 466 | 39 | 8.4 | 5 | 1.1 | 33 | 7.1 | 8 | 1.7 |

| 20-29 | 813 | 92 | 11.3 | 4 | 0.5 | 82 | 10.1 | 23 | 2.8 |

| 30-39 | 437 | 70 | 16.0 | 3 | 0.7 | 56 | 12.8 | 12 | 2.7 |

| 40-48 | 62 | 16 | 25.8 | 3 | 4.8 | 15 | 24.2 | 3 | 4.8 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | |||||||||

| <18.5 | 64 | 8 | 12.5 | 2 | 3.1 | 8 | 12.5 | 3 | 4.7 |

| 18.5-24.9 | 553 | 59 | 10.7 | 6 | 1.1 | 53 | 9.6 | 12 | 2.2 |

| 25.0-29.9 | 515 | 50 | 9.7 | 3 | 0.6 | 41 | 8.0 | 14 | 2.7 |

| 30.0-34.9 | 339 | 46 | 13.6 | 2 | 0.6 | 42 | 12.4 | 12 | 3.5 |

| 35.0-39.9 | 164 | 23 | 14.0 | 1 | 0.6 | 19 | 11.6 | 2 | 1.2 |

| ≥40 | 143 | 31 | 21.7 | 1 | 0.7 | 23 | 16.1 | 3 | 2.1 |

Acute lymphoblastic leukemia, chronic myeloid leukemia acute myeloid leukemia, other leukemia

Ewing sarcoma, osteosarcoma

Carcinoma, germ cell tumor, hepatoblastoma, melanoma, Wilms tumor, retinoblastoma, neuroblastoma, rhabdomyosarcoma, soft tissue sarcoma, other malignancy

Central nervous system tumor

BMI=Body mass index, kg/m2=kilograms per meter squared

Paragraph Number 14 The sensitivity, specificity, accuracy and percent agreement of the SF-36 physical function subscale measure varied by diagnostic group and the outcome standard used. When the 6MW test was used as the comparison standard, sensitivity and specificity ranged from 0.50 and 0.84 among lymphoma survivors to 0.85 and 0.84 in CNS survivors. Accuracies ranged from 0.82 in lymphoma survivors to 0.88 in leukemia survivors. When the PPT was used as the comparison standard, sensitivity and specificity ranged from 0.67 and 0.82 in bone cancer survivors to 0.80 and 0.90 in leukemia survivors. Accuracy ranged from 0.80 in bone cancer to 0.90 in leukemia survivors. Kappa values were better for agreement between the SF-36 physical function subscale measure and the 6MW test than they were for agreement between the Sf-36 physical subscale measure and the PPT.

Characteristics of those who are misclassified by self-report

Paragraph Number 15 When the 6MW test was used as the comparison standard for the SF-36 physical function subscale, 13.0% of the participants were misclassified. Nearly all (10.5%) of the misclassifications were individuals whose SF-36 physical function subscale score indicated that they had a physical performance limitation but whose distance walked in 6 minutes did not indicate a limitation (Table 4). Lymphoma (15.0%) and central nervous system tumor (14.2 %) survivors, survivors >50 years (25.9 %), those with >40 years of survivorship (24.2), and those with a BMI >40 kg/m2 (16.1%) had the highest rates of false positive diagnosis when the 6MW considered the gold standard.

Paragraph Number 16 In multivariable models, CNS survivors were 2.6 times (95% CI 1.5- 4.6) and lymphoma survivors were 1.5 times (95% CI 1.0-2.4) more likely than leukemia survivors to report a physical performance limitation when their 6MW distance did not indicate a limitation (Table 5). In multivariable models, age and body size were also associated with reporting a physical performance limitation when one was not present. For each one year increase in age, the odds ratio of reporting a limitation when one was not present was 1.05 (95% CI 1.01-1.08) in multivariable models. In multivariable models, normal weight individuals were less likely to report a physical performance limitation when one was not present than were than obese individuals (OR 0.7; 95% CI 0.5- 0.9).

Table 5. Odd ratios of misclassification of physical performance limitations.

| 6MW (<= 300): Gold standard | PPT (<= 17): Gold standard | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | P | OR | 95% CI | P | |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Female | 1.33 | 0.97-1.81 | 0.08 | 1.26 | 0.94-1.68 | 0.13 |

| Diagnose | ||||||

| Leukemia | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Bone cancer | 1.14 | 0.58-2.24 | 0.70 | 1.87 | 1.06-3.30 | 0.03 |

| CNS | 2.61 | 1.47-4.63 | 0.001 | 2.47 | 1.39-4.41 | 0.002 |

| Lymphoma | 1.54 | 1.00-2.44 | 0.05 | 1.68 | 1.09-2.58 | 0.02 |

| Other cancer | 0.96 | 0.62-1.51 | 0.87 | 1.32 | 0.87-1.98 | 0.19 |

| Obesity | ||||||

| Yes | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| No | 0.68 | 0.49-0.93 | 0.02 | 0.62 | 0.46-0.84 | 0.002 |

| Age | 1.05 | 1.01-1.08 | 0.01 | 1.05 | 1.02-1.08 | 0.003 |

| Time since diagnose | 1.01 | 0.98-1.05 | 0.50 | 1.01 | 0.98-1.05 | 0.53 |

Paragraph Number 17 When the PPT was used as the comparison standard for the SF-36 physical function subscale, 13.0% of the participants were misclassified. Nearly all (12.2%) of the misclassifications were individuals whose SF-36 physical function subscale score classified them with a physical performance limitation but whose score on the PPT did not indicate a limitation. Lymphoma (17.1%) and bone cancer (17.2 %) survivors, survivors >50 years (31.0 %), those with >40 years of survivorship (25.8), and those with a BMI >40 kg/m2 (21.7%) had the highest rates of false positive diagnosis when the PPT considered the gold standard.

Paragraph Number 18 In multivariable models, CNS tumor, bone tumor, and lymphoma survivors were 2.5 times (95% CI 1.4- 4.4), 1.9 (95% CI 1.1- 3.3) and 1.7 times (95% CI 1.1-2.6) more likely, respectively, than leukemia survivors to report a physical performance limitation when their PPT score did not indicate a limitation. In multivariable models, age and body size were also associated with reporting a physical performance limitation when one was not present. For each one year increase in age, the odds of reporting a limitation when one was not present was 1.05 times (95% CI 1.02-1.08) in multivariable models. In multivariable models, normal weight individuals were less likely to report a physical performance limitation when their PPT score did not indicate a limitation than obese individuals (OR 0.6; 95% CI 0.5- 0.8).

Discussion

Paragraph Number 19 Self-reported physical function has been used widely to indicate the abilities of childhood cancer survivors to successfully navigate their homes, schools, work places and communities for everyday living, social interaction and recreation. Our study indicates that most CCS accurately report their physical performance limitations. Those who incorrectly report physical performance limitations report a problem when one is not clinically apparent. Those with CNS or bone tumors, those who are older and those who are either over or underweight are most likely to misclassify their physical performance status.

Paragraph Number 20 To our knowledge, no study has previously evaluated the accuracy of self-reported physical performance, measured with the physical function subscale of the SF-36, in a cohort of childhood cancer survivors. Our findings are similar to those reported in elderly cohorts from the United States and Spain (10, 18, 19). Kelly-Hayes and colleagues reported that 11% of an elderly cohort in the United States were misclassified when reported task limitation was used to assess poor performance and compared to the clinician's observation of limitation on the same activities (18). As in our study, among those who were misclassified, the majority reported a performance limitation when one was not present according to the clinical measure (18). Ferrer et al reported agreement between self-reported physical limitations on an interview based survey and performance on a four meter walk test in an elderly Spanish cohort that mirror those seen in our cohort (10).

Paragraph Number 21Conversely, our findings are in contrast to research among older adults that have evaluated the influence of data collection methods with physical performance limitations as the outcome of interest. These studies consistently report that surveys, self- or interviewer administered, under estimate the prevalence of physical performance limitations when compared to clinical evaluations (13, 16, 32, 36). This difference may be because childhood cancer survivors, several decades younger than members of these elderly cohorts, have different perceptions of impaired physical function, focused more on aerobic capacity and mobility and less on activities necessary for simple daily living. Accordingly, in our cohort, the 6MW had better agreement with self-reported physical function than did the PPT.

Paragraph Number 22 A secondary analysis of those who self-reported a physical performance limitation showed that those most likely to report a limitation were also most likely to be misclassified by the SF-36 physical function subscale. For example, survivors of lymphoma, CNS tumors, and bone tumors were more likely than leukemia survivors to self-report a limitation according to the SF-36 physical function subscale, and also more likely to report a limitation when one was not detectable by either the 6MW test or PPT criteria. Additionally, rates of disability by self report among older study participants or those who were under weight or obese were higher. These survivors were more likely to report a limitation when one was not clinically detectable. These findings complicate assessment of physical function since those who appear most at risk for physical performance limitations are also most likely to be misclassified when self-report is used to capture these outcomes.

Paragraph Number 23 Measurement of physical performance limitations is difficult and previous work suggests that a global approach to function is needed to correctly classify physical function status(4, 6). When evaluating physical function among childhood cancer survivors, it is also important to consider that they may have emotional and cognitive outcomes that influence both their abilities to report and their perceptions of their physical abilities(20). The physical function subscale of the SF-36 is a component of a larger generic health-related quality of life instrument, and reporting on this measure certainly is influenced by cognitive and emotional constructs. The PPT (a tool designed to assess dimensions of physical function common in everyday life) and 6MW test (a tool that evaluates aerobic capacity and mobility) are more direct measures of immediate performance, and are less likely than a self-report measure to be influenced by cognitive abilities and emotional overlay. The inclusion of tools that directly evaluate physical function may be a useful addition to traditional self-reported measures.

Paragraph Number 24 The findings of this study should be considered in the context of potential limitations. First, not all of the individuals eligible for our study participated. It is possible that those who chose not to or who were unable to participate had more or fewer physical performance limitations than those who were able to participate. Because we could not assess physical performance limitations in non-participants, we have no way to evaluate the magnitude or direction of this bias. Second, the participants in our cohort were more likely to be female than the non-participants. Because our results did not differ by sex, this is unlikely to have impacted our findings (25). Additionally, the instruments and cut points we selected, while validated and widely used in cancer survivor and other populations, (12, 15, 26, 31, 40) are not the only measures of physical performance available. Other self-report measures may have better concordance with the 6MW test and, or the PPT. Finally, cell sizes were small for the comparisons between the SF-36 and the PPT, and when data were stratified by diagnosis and gender. This increased the variability of our estimates and made it difficult to draw conclusions about measured versus self-reported physical performance limitations in specific subgroups.

Paragraph Number 25 Nevertheless, our analysis provides preliminary information that indicates that self-report, while not perfect, accurately identifies individuals without physical performance limitations. In contrast, self-report is less reliable for identifying individuals with physical performance limitations with only a modest level of sensitivity. Interpretation of self-report data regarding physical performance should take into account the potential for misclassification. Our results show that a using self-report misclassified some survivors of childhood cancer as having a physical performance limitation when one is not detected with clinical performance measures, which likely inflates overall prevalence estimates of this outcome in the childhood cancer survivor population. Our results also identify survivors whose self-report data may be less optimistic about their performance than is their actual physical performance when evaluated with a clinical tool.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The results of the present study do not constitute endorsement by the American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM).

Grant Support: This work was supported in part by the Cancer Center Support (CORE) grant CA 21765 from the National Cancer Institute, grant 5R25CA02394 from the National Cancer Institute, and by the American Lebanese Syrian Associated Charities (ALSAC).

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest.

Supplemental Digital Content: Supplemental Digital Content 1.doc

References

- 1.Altman DG, Bland JM. Statistics Notes: Diagnostic tests 1: sensitivity and specificity. BMJ. 1994;308(6943):1552. doi: 10.1136/bmj.308.6943.1552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alvarez JA, Scully RE, Miller TL, et al. Long-term effects of treatments for childhood cancers. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2007;19(1):23–31. doi: 10.1097/MOP.0b013e328013c89e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bohannon RW, DePasquale L. Physical Functioning Scale of the Short-Form (SF) 36: internal consistency and validity with older adults. J Geriatr Phys Ther. 2010;33(1):16–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bowling A. Mode of questionnaire administration can have serious effects on data quality. J Public Health (Oxf) 2005;27(3):281–91. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdi031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brown M, Sinacore DR, Binder EF, Kohrt WM. Physical and performance measures for the identification of mild to moderate frailty. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2000;55(6):M350–5. doi: 10.1093/gerona/55.6.m350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Butland RJ, Pang J, Gross ER, Woodcock AA, Geddes DM. Two-, six-, and 12-minute walking tests in respiratory disease. BMJ. 1982;284(6329):1607–8. doi: 10.1136/bmj.284.6329.1607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cote CG, Casanova C, Marín JM, et al. Validation and comparison of reference equations for the 6-min walk distance test. European Respir J. 2008;31(3):571–8. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00104507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Delbaere K, Van den Noortgate N, Bourgois J, Vanderstraeten G, Tine W, Cambier D. The Physical Performance Test as a predictor of frequent fallers: a prospective community-based cohort study. Clin Rehabil. 2006;20(1):83–90. doi: 10.1191/0269215506cr885oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Enright PL, Sherrill DL. Reference equations for the six-minute walk in healthy adults. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998;158(5 Pt 1):1384–7. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.158.5.9710086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ferrer M, Lamarca R, Orfila F, Alonso J. Comparison of performance-based and self-rated functional capacity in Spanish elderly. Am J Epidemiol. 1999;149(3):228–35. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gulmans VA, van Veldhoven NH, de Meer K, Helders PJ. The six-minute walking test in children with cystic fibrosis: reliability and validity. Pediatr Pulmonol. 1996;22(2):85–9. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-0496(199608)22:2<85::AID-PPUL1>3.0.CO;2-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hayes KW, Johnson ME. Measures of adult general performance tests: The Berg Balance Scale, Dynamic Gait Index (DGI), Gait Velocity, Physical Performance Test (PPT), Timed Chair Stand Test, Timed Up and Go, and Tinetti Performance-Oriented Mobility Assessment (POMA) Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2003;49(S5):S28–S42. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hebert R, Raiche M, Gueye NR. Survey disability questionnaire does not generate valid accurate data compared to clinical assessment on an older population. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2012;54(2):e57–62. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2011.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Howlader N, Noone AM, Krapcho M, Neyman N, Aminou R, Altekruse SF, Kosary CL, Ruhl J, Tatalovich Z, Cho H, Mariotto A, Eisner MP, Lewis DR, Chen HS, Feuer EJ, Cronin KA, editors. Vintage 2009 Populations. 2012. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975-2009. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jay SJ. Reference equations for the six-minute walk in healthy adults. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;161(4 Pt 1):1396. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.161.4.16147a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jette AM. How measurement techniques influence estimates of disability in older populations. Soc Sci Med. 1994;38(7):937–42. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)90426-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kasymjanova G, Correa JA, Kreisman H, et al. Prognostic value of the six-minute walk in advanced non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2009;4(5):602–7. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31819e77e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kelly-Hayes M, Jette AM, Wolf PA, D'Agostino RB, Odell PM. Functional limitations and disability among elders in the Framingham Study. Am J Public Health. 1992;82(6):841–5. doi: 10.2105/ajph.82.6.841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Merrill SS, Seeman TE, Kasl SV, Berkman LF. Gender differences in the comparison of self-reported disability and performance measures. The journals of gerontology. Series A, Biological sciences and medical sciences. 1997;52(1):M19–26. doi: 10.1093/gerona/52a.1.m19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ness KK, Gurney JG, Zeltzer LK, et al. The impact of limitations in physical, executive, and emotional function on health-related quality of life among adult survivors of childhood cancer: a report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2008;89(1):128–36. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2007.08.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ness KK, Hudson MM, Ginsberg JP, et al. Physical performance limitations in the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study cohort. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(14):2382–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.21.1482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ness KK, Mertens AC, Hudson MM, et al. Limitations on Physical Performance and Daily Activities among Long-Term Survivors of Childhood Cancer. Ann Intern Med. 2005;143(9):639–47. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-143-9-200511010-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ness KK, Wall MM, Oakes JM, Robison LL, Gurney JG. Physical performance limitations and participation restrictions among cancer survivors: a population-based study. Ann Epidemiol. 2006;16(3):197–205. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2005.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Oeffinger KC, Mertens AC, Sklar CA, et al. Chronic health conditions in adult survivors of childhood cancer. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(15):1572–82. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa060185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ojha RP, Oancea SC, Ness KK, et al. Assessment of potential bias from non-participation in a dynamic clinical cohort of long-term childhood cancer survivors: Results from the St. Jude lifetime cohort study. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2012;60(5):856–64. doi: 10.1002/pbc.24348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pinar R. Reliability and construct validity of the SF-36 in Turkish cancer patients. Qual Life Res. 2005;14(1):259–64. doi: 10.1007/s11136-004-2393-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reuben DB, Siu AL. An objective measure of physical function of elderly outpatients. The Physical Performance Test. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1990;38(10):1105–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1990.tb01373.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reulen RC, Winter DL, Lancashire ER, et al. Health-status of adult survivors of childhood cancer: a large-scale population-based study from the British Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. International journal of cancer. Journal international du cancer. 2007;121(3):633–40. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reulen RC, Zeegers MP, Jenkinson C, et al. The use of the SF-36 questionnaire in adult survivors of childhood cancer: evaluation of data quality, score reliability, and scaling assumptions. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2006;4:77. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-4-77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ries L, Melbert D, Krapcho M, et al. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975-2005. 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rostagno C, Olivo G, Comeglio M, et al. Prognostic value of 6-minute walk corridor test in patients with mild to moderate heart failure: comparison with other methods of functional evaluation. Eur J Heart Fail. 2003;5(3):247–52. doi: 10.1016/s1388-9842(02)00244-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rothwell PM, McDowell Z, Wong CK, Dorman PJ. Doctors and patients don't agree: cross sectional study of patients' and doctors' perceptions and assessments of disability in multiple sclerosis. BMJ. 1997;314(7094):1580. doi: 10.1136/bmj.314.7094.1580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rueegg CS, Michel G, Wengenroth L, von der Weid NX, Bergstraesser E, Kuehni CE. Physical performance limitations in adolescent and adult survivors of childhood cancer and their siblings. PLoS One. 2012;7(10):e47944. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0047944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schmitz KH, Holtzman J, Courneya KS, Masse LC, Duval S, Kane R. Controlled physical activity trials in cancer survivors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2005;14(7):1588–95. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-04-0703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Siegel S, Castellan NJ. Nonparametric statistics for the behavioral sciences. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1988. p. 311. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Walsh EG, Khatutsky G. Mode of Administration Effects on Disability Measures in a Sample of Frail Beneficiaries. The Gerontologist. 2007;47(6):838–44. doi: 10.1093/geront/47.6.838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ware JE. SF-36 physical and mental health summary scales : a user's manual. Boston: The Health Institute, New England Medical Center; 1994. p. 188. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ware JE. SF-36 health survey : manual and interpretation guide. In: Lincoln RI, editor. QualityMetric. Boston, Mass: Health Assessment Lab; 2000. p. 238. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ware JEJ. SF-36 Health Survey Update. Spine. 2000;25(24):3130–9. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200012150-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zugck C, Krüger C, Dürr S, et al. Is the 6-minute walk test a reliable substitute for peak oxygen uptake in patients with dilated cardiomyopathy? Eur Heart J. 2000;21(7):540–9. doi: 10.1053/euhj.1999.1861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.