Abstract

Pediatric HIV infection remains a global health crisis with a worldwide infection rate of 2.5 million (WHO, Geneva Switzerland, 2009). Children are much more susceptible to HIV-1 neurological impairments than adults, which is exacerbated by co-infections. A major obstacle in pediatric HIV research is sample access. The proposed studies take advantage of ongoing pediatric SIV pathogenesis and vaccine studies to test the hypothesis that pediatric SIV infection diminishes neuronal populations and neurogenesis in the hippocampus. Newborn rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta) that received intravenous inoculation of highly virulent SIVmac251 (n=3) or vehicle (control n=4) were used in this study. After a 6–18 week survival time, the animals were sacrificed and the brains prepared for quantitative histopathological analysis. Systematic sections through the hippocampus were either Nissl stained or immunostained for doublecortin (DCX+), a putative marker of neurogenesis. Using design-based stereology, we report a 42% reduction in the pyramidal neuron population of the CA1, CA2, and CA3 fields of the hippocampus (p < 0.05) in SIV-infected infants. The DCX+ neuronal population was also significantly reduced within the dentate gyrus of the hippocampus. The loss of hippocampal neurons and neurogenic capacity may contribute to the rapid neurocognitive decline associated with pediatric HIV infection. These data suggest that pediatric SIV infection, which leads to significant neuronal loss in the hippocampus within 3 months, closely models a subset of pediatric HIV infections with rapid progression.

Keywords: Hippocampus, Stereology, pediatric SIV, Doublecortin

INTRODUCTION

An estimated 1,500 children under the age of 15 years become infected with HIV-1 daily in resource poor areas, with most being perinatally infected through mother-to-child-transmission (MTCT) [1]. Though approximately 100 countries have implemented prevention of mother to child transmission (PMTCT) of HIV, only an estimated 10% of pregnant women are offered this service worldwide and less than 6% in resource poor areas. Perinatal transmission rates in developing nations remain high despite the UNAIDS effort to eliminate new HIV infections among children by 2015 [1]. Within the United States there is a perinatal infection rate of 1–3% annually despite early identification and triple anti-retroviral therapy (ART). The developing immune system is more susceptible than the adult to adverse viral infections [2] with about 25% of HIV-infected infants dying before their second birthday [3].

Infants are disproportionately affected by HIV-1 related neurological impairments in comparison to adults [4, 5]with children often displaying neurobehavioural deficits prior to significant immunosuppression [6]. Imaging studies from HIV-1 positive children have shown gross brain disturbances resulting in ventrical enlargement, sulcal widening, white matter lesions, encephalopathy, global cortical atrophy, basal ganglia calcifications, altered metabolite concentrations in the frontal cortex and hippocampus and potential demylenation of the corpus callosum [6–8]. Neurobehavioural deficits suggest dysfunction of the frontal cortex as well as the hippocampus with affected children presenting a range of fine and gross motor impairments, cognitive delays, verbal deficits, memory deficits,visual impairment, abnormal muscle tone, and spasticity [4, 6, 7].

Neonatal rodent models of intracranial HIV-1 tat antigen administration further support clinical evidence that the neurons of the hippocampus, as well as hippocampal neurogenesis, are particularly susceptible to the neurotoxic cascade of HIV-1 proteins [9]. Scarce pathology reports from HIV-infected children have provided evidence of apoptosis in the cerebral cortex associated with perivascular inflammation [10], but have been limited in addressing HIV induced neuropathogenesis. Due to the persistent rates of HIV-1 infection in developing nations (2–4), an assessment of the impact of early HIV-1 infection on brain development is urgently needed. A significant barrier to pediatric HIV-1 neurological research is sample access [2].

Non-human primates offer a valid alternative due to the fact that infant macaques show similar neuroanatomical and immune system development to human infants [2]. Furthermore, human immunodeficiency virus and simian immunodeficiency virus infections share a similar pathophysiology and MTCT is replicable in monkeys [2]. The pathogenic uncloned SIVmac251 isolate used in the current study closely models a subset of pediatric HIV-infection with persistently high virus replication and rapid progression; infant macaques progress to simian AIDS (SAIDS) within 6 months. In light of the clinical manifestations of pediatric HIV infection and the effects of HIV-related proteins on the developing rodent brain we tested the hypothesis that SIV infection deleteriously affects the integrity of the hippocampus by reducing the pyramidal and immature neuronal populations in a pediatric model of HIV infection.

METHODS

Newborn rhesus macaques (Macacca mulatta) were hand-reared in the nursery of the California National Primate Research Center (CNPRC) in accordance with American Association for Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care Standards. We strictly adhered to the “Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals” prepared by the Committee on Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the Institute of Laboratory Resources, National Resource Council. The experimental protocol was reviewed and approved by the University of California Davis Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. A total of 7 neonatal monkeys were randomly assigned to one of two groups (Group 1-control, n=4; Group 2- SIV infection, n=3). Within 72 hours after birth, subjects in group 2 received intravenous inoculation with 100 tissue culture doses 50% (TCID50) of SIVmac251 obtained from the Analytical and Resource Core at CNPRC [2]. Plasma viral loads were quantified by real-time RT-PCR [11]. Although the dose of this virus inoculum is still higher than how most human infants acquire perinatal HIV infection, this moderate dose was selected to obtain a 100% infection rate in a well-established animal model of perinatal infection.[2,].

The SIV-infected infants were euthanized between 7 and 10 weeks of age (Table 1) when they met the established clinical criteria for euthanasia of retrovirus-infected animals (including symptoms like lethargy, weight loss, dehydration, diarrhea and opportunistic infections unresponsive to standard treatments). The brains were extracted, post-fixed in 10% formalin, blocked into 1-cm slabs in the coronal plane, cryoprotected in 30% buffered sucrose, and frozen at −80°C until further processing. Ten parallel series of coronal sections (50μm) were obtained from each animal with the first series being Nissl stained with cresyl-violet for design-based stereology. The remaining series were placed in antigen preserve (50% ethylene glycol, phosphate buffer pH=7.4, and 1% polyvinal pyrrolodone) and stored at −20°C for future immunohistochemical analysis.

Table 1.

Subject Profile

| Subject | Group | Specific Gravity (g/ml) |

Anterior-Posterior (mm) |

Plasma SIVrna copies/ml |

Age at euthanasia (weeks) |

Weight at time of euthanasia (kg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 41615 | SIVmac251 | 1.0401 | 67.1 | 650,000,000 | 10 | 0.746 |

| 41614 | SIVmac251 | 1.2207 | 63.7 | 240,000,000 | 7 | 0.780 |

| 41622 | SIVmac251 | 0.9699 | 69.0 | 160,000,000 | 10 | 0.736 |

| 40967 | control | 0.9586 | 71.1 | – | 15 | 1.360 |

| 40929 | control | 0.9160 | 71.5 | – | 16 | 1.090 |

| 41656 | control | 1.0280 | 69.3 | – | 16 | 1.210 |

| 41660 | control | 1.0387 | 70.6 | – | 16 | 1.181 |

Specific gravity was determined by brain weight (g) over water displacement (ml). The anteriorior-posterior measurements were taken with a caliper and plasma viral load was determined via real time RT-PCR. Hippocampal pyramidal neuronal population remains steady over the course of the first two years of life [12]. Therefore reductions in the pyramidal neuronal population are likely to reflect the effects of SIV infection as opposed to age related differences.

Design-Based Stereology

Total estimation of the pyradimal neuronal population of the hippocampus cornu ammonis fields (CA1-3) was achieved using the optical fractionator method. Sampling parameters are similar to previously described methods of design-based stereology in the primate hippocampus [13]. Briefly, sections topography and superimposed counting frames (disectors) were generated through the MicroBrightField StereoInvestigator program (Williston, Vermont, USA) attached to a Nikon Eclipse microscope under 4x (topography) and 60x (counting objective: Plan Fluor oil-immersion, N.A.=1.4) objectives. For the stereological parameters in this study every 20th section was selected with a random starting point within 500μm of the beginning of the CA fields and continued to the CA fields were no longer visible. Sampling in the absence of a visible dentate gyus granular layer of the most anterior and posterior regions ensured an estimation of the entire CA hippocampal neuronal population. The total estimation of pyramidal neuronal numbers (N) was calculated by the following equation:

Where ssf is section-sampling fraction, asf is area-sampling fraction, tsf is thickness-sampling fraction (where the measured thickness of the tissue is divided by the dissector height), and ΣQ− is total number of objects of interest counted. For this study, a neuron was defined as having a visible centrally located nucleolus and defined cytoplasm. The average coefficient of error (CE) for total number of neurons was determined to assess reliability of measurements.

Immunohistochemistry

A complete series of sections spanning the entire hippocampus area was taken from the developmental brain bank to undergo doublecortin staining (DCX), a putative marker of immature neurons [14]. Standard batch immunohistochemical techniques were followed for the DCX immunohistochemistry. Briefly, free floating sections were rinsed in PBS 3 times, incubated for 1 hour in a pretreatment (3% hydrogen peroxide, 20% methanol in PBS), blocked for 1 hour in 3% normal horse serum and then incubated overnight in goat anti-DCX (1:400 Santa Cruz #sc-8066) at room temperature. The next day, sections were washed in PBS and incubated in horse anti-goat secondary antibody (1:200, Vector) for 1.5 hours, followed by 1.5 hours in ABC (Vector) and visualized with DAB (Sigma). Next, sections were wet-mounted on gelatinized slides and air dried overnight. The following day, sections were dehydrated in graded ethanol (50–100%), cleared in xylene and coverslipped with DPX mounting media (VWR Int. Poole, UK).

Statistical analysis

Statistical differences were determined using the Mann-Whitney U test of significance on the GraphPad InStat3 program (La Jolla, California, USA). The coefficient of variation (CV = SD/mean), presented in parenthesis was calculated for neuronal numbers and volume estimation. The CE for the different measurements was calculated as .

Results

One section of every 20th section (SSF) was selected from the entire rostral-caudal extent of the hippocampus. The first sections were taken from the CA1 subfield, which produced a set sample of 13–16 sections throughout the rostral-caudal region. Standard scan grid sizes of 500μm × 500μm, 250μm × 250μm, and 350μm × 350μm were used for CA1, CA2, and CA3 respectively. For each disector site a standard 40μm × 40μm × 10μm counting frame was employed. Section thickness was measured at each counting site with an average measured thickness of 17.87μm, which provided an average guard height of 3.93μm(Table 2).

Table 2.

Stereology Parameters

| Subregion | Section Sampling Fraction | Average Number Sections | Dissector Volume μm3 (x*y*z) |

Average Tissue Thickness | Mean ΣF |

x-y Step | Mean ΣQ- |

Mean Vref (mm3) |

Mean N (in mil-lions) |

Mean CE (N)* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | ||||||||||

| CA1 | 1/20 | 15 | 16000 | 17.7 | 201 | 500 | 363.3 | 44.3 | 1.996 | 0.055 |

| CA2 | 1/20 | 15 | 16000 | 17.1 | 159 | 250 | 333.0 | 7.8 | 0.434 | 0.058 |

| CA3 | 1/20 | 15 | 16000 | 16.7 | 263 | 350 | 464.0 | 28.4 | 1.182 | 0.048 |

| SIV+ | ||||||||||

| CA1 | 1/20 | 14 | 16000 | 19.0 | 144 | 500 | 190.3 | 30.3* | 1.106* | 0.073 |

| CA2 | 1/20 | 14 | 16000 | 18.5 | 138 | 250 | 167.7 | 6.6 | 0.240* | 0.077 |

| CA3 | 1/20 | 14 | 16000 | 18.2 | 219 | 350 | 265.3 | 23.0 | 0.730* | 0.064 |

The average CE for the number of neurons for all three regions of the hippocampus were respectively <0.073 for CA1, <0.078 for CA2 and <0.064 for CA3 indicating an acceptable variation for this sampling scheme. There was a significant volume reduction restricted to the CA1 (p = 0.0286). The estimation of neurons produced a ratio BCV2/CV2 of greater than 0.85 for both groups indicating low sampling error and a precise estimate of hippocampal neuronal population.ΣF is the average number of disectors imaged per subject and meanΣQ- is the average number of neurons counted for each subject.

p = 0.0286 SIV vs control.

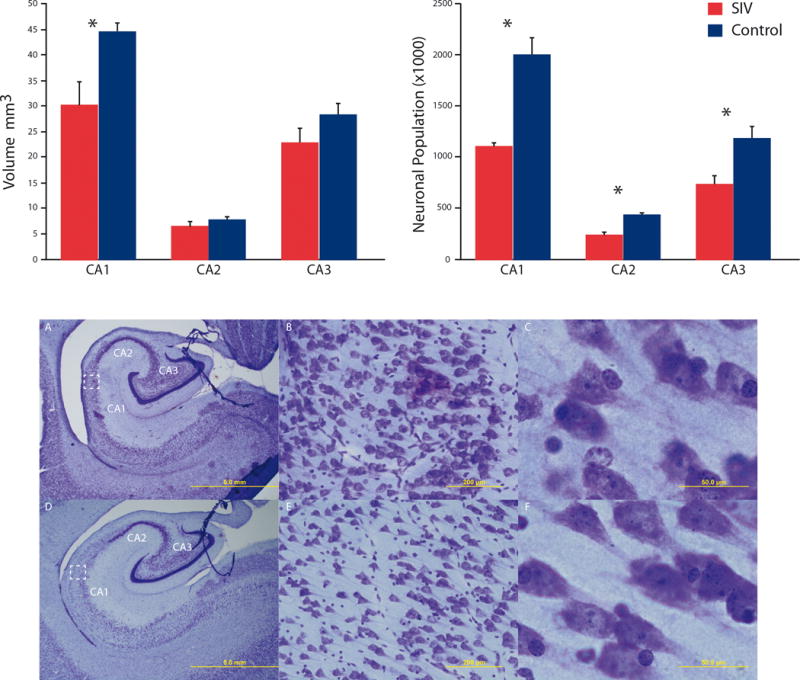

Perinatal SIV infection resulted in an overall average of 42% reduction (Figure 1) in the total number pyramidal neuronal population (p = 0.0286). There were significant neuronal reductions in the CA1 region (1.106 × 106, CV = 0.05 SIV+ vs 1.996 × 106, CV = 0.145 control), CA2(0.240 × 106, CV = 0.173 SIV+ vs 0.434 × 106, CV = 0.057 control), and CA3(0.730 × 106, CV = 0.189 SIV+ vs1.182 × 106, CV = 0.174control) in SIV+ versus control subjects (p = 0.0286 for each group; Figure 1). The estimation of neurons produced a ratio BCV2/CV2 of greater than 0.85 for both groups indicating low sampling error and a precise estimate of hippocampal neuronal population.

Figure 1. Hippocampal Pyramidal Neuronal Population.

Neuonal populations were reduced in CA1-3 fields with an reduction in CA1 volume (p< 0.05). SIV infected infants (A–C) displayed gross morphological differences such as enlarged ventricles and thinned pryamidal layers compared to control subjects (D–F). Magnifications of 1.25× (A & D), 20× (B & E) and 100× (C & F) are displayed above; scale bars = 5mm, 200μm, and 50μm respectively.

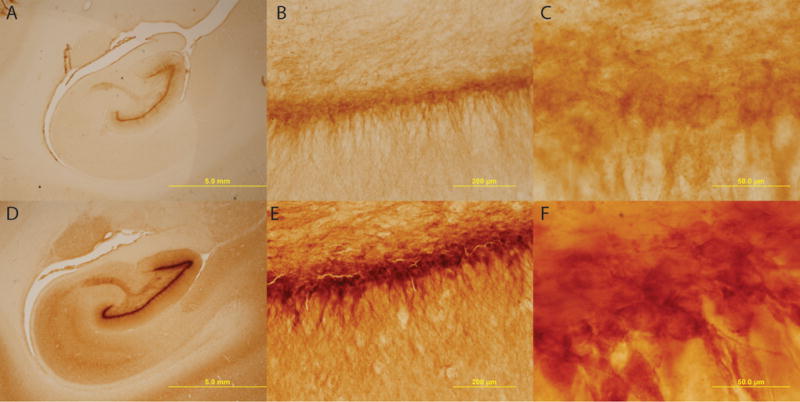

Immunostaining of the hippocampus for DCX indicated an observable reduction in immature neurons of the dentate gyrus. The reduced pattern of DCX+ neurons was apparent in each SIV+ subject whereas in the control subjects, the density of immature neurons occluded visible identification of individual neurons (Figure 2).

Figure 2. DCX+ Immature Neurons.

There is an apparent lack of DCX+ neurons observed in the dentate gyrus of SIV+ subjects (A–C) as compared to control subjects (D–F). Magnifications of 1.25× (A & D), 20× (B & E) and 100× (C & F) are displayed above; scale bars = 5mm, 200μm, and 50μm respectively.

Discussion

Using a perinatal MTCT non-human primate model to study the neuropathogenesis of SIV infection, we provide evidence of loss of pyramidal neurons of the CA1-3 fields along with a dramatic reduction in immature neurons within the first three months of infection. While much of the clinical research focuses on global cortical changes and the basal ganglia [6–8], there is increasing evidence of HIV-1 related toxicity in the hippocampus [9, 15–18]. Neural atrophy of the hippocampus is also reported in young adult monkeys following SIV infection [19]. Intracranial injections of the HIV-1 associated proteins gp120 and Tat in neonatal rats have been found to significantly reduce neuronal populations of the CA2 and CA3 fields of the hippocampus [9, 20] and suppress long-term potentiation of CA1 neurons [20] which was correlated to declines in spatial memory [9]. Additionally, HIV-1 gene sequences have been detected in the hippocampus of post-mortem brains [17]

The paucity of hippocampal neurons following neonatal SIV infection provides anatomical evidence for memory impairments in HIV infected children. Under normal developmental conditions the pyramidal neuronal population remains stable during the first two years of life, while neurogenesis in the dentate gyrus peaks during the first three months [13]. Thus any damage of the hippocampus structure/function will likely result in long-term neurological consequences as reported in HIV positive children [18]. HIV-1 has been reported in neural progenitors of archival pediatric brain tissue providing clinical evidence of an interaction between HIV-1 and neural progenitors [16]. In vitro, both gp120 and Tat proteins have been found to attenuate proliferation of human neural progenitor cells (hNPCs) [18]without affecting the viability of pre-existing hNPCs [18]. A novel finding in this study is the apparent reduction in DCX+ neurons in the dentate gyrus. Whether this reflects a neurotoxic effect on established immature neurons, an acceleration of the maturation process as a repair mechanism, or an attenuation of neural progenitor proliferation remains to be determined.

Neuroinflammation and breakdown of the blood brain barrier (BBB) have been implicated as mechanisms contributing to HIV-1 related neurological disorders [21–24]. Once the virus transverses the BBB, its ability to infect cells depends on the presence of CCR5 and CXCR4, which increases in expression from birth to 9 months of age in the primate hippocampus [25]. Expression of CD4 receptors and the chemokine co-receptors CCR5 and CXCR4 play an important role in the pathogenesis of HIV [25] and signaling through these receptors results in a balance between survival/pro-inflammatory neuronal death [26]. These receptors are expressed on neural progenitor cells and have been proposed to play a role in HIV induced reductions in neurogenesis [24, 27]

CONCLUSION

The extent of HIV-1 infection of specific cell types, neuronal loss, and its mechanism of action in infants is currently unknown [6], severely limiting the ability to develop and evaluate therapeutic paradigms to minimize the neurological impairments as a result of HIV-1 infection. Proliferating NPCs in the dentate gyrus can be upregulated with the serotonin specific re-uptake inhibitor paroxetine even in the presence of HIV Tat protein [18]. Neurobehavioural and cognitive dysfunction remains prevalent in perinatally infected children even if they receive combination ART [4, 6, 8]. Although ART suppresses peripheral viral replication, it has a relatively low bioavailability in the central nervous system thereby allowing the brain to be a viral reservoir and potentially exacerbating neuropathogenesis of pediatric HIV infection [6]. In order to take advantage of developmental plasticity in future potential therapeutic interventions aimed at minimizing neurological impairment by pediatric HIV infection as well as co-infections (e.g. tuberculosis and malaria), it is necessary to define the response to HIV-1 infection during the early developmental period.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr. Thomas Heinbockel for his grant support (S06GM08016 MBRS-SCORE, NIGMS/NIH) to K.B. We would also like to thank the technical support of Devon Jackscon, Sanche Graham, and Mamadou M’Baye. Dr. Kebreten Manaye for the generous use of her MicroBrightfield Stereology System.

Support: Leadership Alliance to MR; District of Columbia Developmental Center for AIDS Research (P30A1087714) and Latham Foundation Grant to MB; S06GM08016 MBRS-SCORE to Thomas Heinbockel in support of KB; NIGMS/NIH1RO1DE019064 (NIH/NIDCR) and 2P30 AI050410 to KA; and P51RR000169 (National Center for Research Resources) to CNPRC.

References

- 1.UNAIDS. It takes a village: ending mother-to-child transmission a partnership uniting the Millennium Villages Project and UNAIDS. 2010 in http://search.unaids.org/search.asp?lg=en&search=it%20takes%20a%20village.

- 2.Abel K. The rhesus macaque pediatric SIV infection model – a valuable tool in understanding infant HIV-1 pathogenesis and for designing pediatric HIV-1 prevention strategies. Curr HIV Res. 2009;7(1):2–11. doi: 10.2174/157016209787048528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Becquet R, et al. Children who acquire HIV infection perinatally are at higher risk of early death than those acquiring infection through breastmilk: a meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2012;7(2):e28510. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Govender R, et al. Neurologic and neurobehavioral sequelae in children with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV-1) infection. J Child Neurol. 2011;26(11):1355–64. doi: 10.1177/0883073811405203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lindl KA, et al. HIV-associated neurocognitive disorder: pathogenesis and therapeutic opportunities. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2010;5(3):294–309. doi: 10.1007/s11481-010-9205-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Van Rie A, et al. Neurologic and neurodevelopmental manifestations of pediatric HIV/AIDS: a global perspective. Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 2007;11(1):1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpn.2006.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hoare J, et al. Erratum to: A diffusion tensor imaging and neuropsychological study of prospective memory impairment in South African HIV positive individuals. Metab Brain Dis. 2013 doi: 10.1007/s11011-012-9311-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nagarajan R, et al. Neuropsychological function and cerebral metabolites in HIV-infected youth. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2012;7(4):981–90. doi: 10.1007/s11481-012-9407-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fitting S, Booze RM, Mactutus CF. Neonatal intrahippocampal injection of the HIV-1 proteins gp120 and Tat: differential effects on behavior and the relationship to stereological hippocampal measures. Brain Res. 2008;1232:139–54. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2008.07.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gelbard HA, et al. Apoptotic neurons in brains from paediatric patients with HIV-1 encephalitis and progressive encephalopathy. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 1995;21(3):208–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2990.1995.tb01052.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cline AN, et al. Highly sensitive SIV plasma viral load assay: practical considerations, realistic performance expectations, and application to reverse engineering of vaccines for AIDS. J Med Primatol. 2005;34(5–6):303–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0684.2005.00128.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Semba RD, Neville MC. Breast-feeding, mastitis, and HIV transmission: nutritional implications. Nutr Rev. 1999;57(5 Pt 1):146–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.1999.tb01795.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jabes A, et al. Postnatal development of the hippocampal formation: a stereological study in macaque monkeys. J Comp Neurol. 2011;519(6):1051–70. doi: 10.1002/cne.22549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rao MS, Shetty AK. Efficacy of doublecortin as a marker to analyse the absolute number and dendritic growth of newly generated neurons in the adult dentate gyrus. Eur J Neurosci. 2004;19(2):234–46. doi: 10.1111/j.0953-816x.2003.03123.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fitting S, et al. Differential long-term neurotoxicity of HIV-1 proteins in the rat hippocampal formation: a design-based stereological study. Hippocampus. 2008;18(2):135–47. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schwartz L, et al. Evidence of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection of nestin-positive neural progenitors in archival pediatric brain tissue. J Neurovirol. 2007;13(3):274–83. doi: 10.1080/13550280701344975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Torres-Munoz J, et al. Detection of HIV-1 gene sequences in hippocampal neurons isolated from postmortem AIDS brains by laser capture microdissection. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2001;60(9):885–92. doi: 10.1093/jnen/60.9.885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee MH, et al. Rescue of adult hippocampal neurogenesis in a mouse model of HIV neurologic disease. Neurobiol Dis. 2011;41(3):678–87. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2010.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Luthert PJ, et al. Hippocampal neuronal atrophy occurs in rhesus macaques following infection with simian immunodeficiency virus. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 1995;21(6):529–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2990.1995.tb01099.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fitting S, et al. Synaptic dysfunction in the hippocampus accompanies learning and memory deficits in human immunodeficiency virus type-1 Tat transgenic mice. Biol Psychiatry. 2013;73(5):443–53. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.09.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shiu C, et al. HIV-1 gp120 as well as alcohol affect blood-brain barrier permeability and stress fiber formation: involvement of reactive oxygen species. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2007;31(1):130–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00271.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Blumberg BM, Gelbard HA, Epstein LG. HIV-1 infection of the developing nervous system: central role of astrocytes in pathogenesis. Virus Res. 1994;32(2):253–67. doi: 10.1016/0168-1702(94)90044-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang H, Sun J, Goldstein H. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection increases the in vivo capacity of peripheral monocytes to cross the blood-brain barrier into the brain and the in vivo sensitivity of the blood-brain barrier to disruption by lipopolysaccharide. J Virol. 2008;82(15):7591–600. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00768-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kaul M. HIV’s double strike at the brain: neuronal toxicity and compromised neurogenesis. Front Biosci. 2008;13:2484–94. doi: 10.2741/2860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Westmoreland SV, et al. Developmental expression patterns of CCR5 and CXCR4 in the rhesus macaque brain. J Neuroimmunol. 2002;122(1–2):146–58. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(01)00457-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shepherd AJ, et al. Distinct modifications in Kv2.1 channel via chemokine receptor CXCR4 regulate neuronal survival-death dynamics. J Neurosci. 2012;32(49):17725–39. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3029-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tran PB, Miller RJ. HIV-1, chemokines and neurogenesis. Neurotox Res. 2005;8(1–2):149–58. doi: 10.1007/BF03033826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]