Abstract

This paper describes the application of a translational research model in developing The Trial Using Motivational Interviewing and Positive Affect and Self-Affirmation in African-Americans with Hypertension (TRIUMPH), a theoretically-based, randomized controlled trial. TRIUMPH targets blood pressure control among African-Americans with hypertension in a community health center and public hospital setting. TRIUMPH applies positive affect, self-affirmation, and motivational interviewing as strategies to increase medication adherence and blood pressure control. A total of 220 participants were recruited in TRIUMPH and are currently being followed. This paper provides a detailed description of the theoretical framework and study design of TRIUMPH and concludes with a critical reflection of the lessons learned in the process of implementing a health behavior intervention in a community-based setting. TRIUMPH provides a model for incorporating the translational science research paradigm to conducting pragmatic behavioral trials in a real-world setting in a vulnerable population. Lessons learned through interactions with our community partners reinforce the value of community engagement in research.

Keywords: Clinical Trial Design, Clinical Trial Implementation, Behavioral Science Research Health Disparities Research, Community Engagement

1. Introduction

African-Americans are disproportionately impacted by hypertension and its related morbidity and mortality. Compared to Caucasians, African-Americans have almost twice the rate of fatal stroke, a 1.5 times greater rate of cardiac mortality, and a 4 times greater rate of end-stage renal disease.[1] A major contributing, yet modifiable factor related to racial disparities in hypertension, is medication adherence. Compared to Caucasians, African-Americans are almost twice as likely to be non-adherent when it comes to taking their blood pressure medications.[2] Given the emphasis on health behavior change, health disparities research focusing on medication adherence would benefit from the integration of social science theory. The translational behavioral science research paradigm provides a contemporary model for research and serves as a roadmap to advancing health disparities research.

Translational behavioral science research links what we know about basic human behavior to developing effective interventions and community-based health promotion programs. It is a two phase process. The first phase, ‘Type I translation,’ entails identifying and selecting social science theories that are most applicable to the behavioral patterns of interest and subsequently testing their efficacy in a clinical setting.[3] Health behavior modification such as improving medication adherence is complex and involves multiple psychosocial and behavioral variables. Therefore, selecting a relevant theory is critical to informing intervention components and in helping to elucidate mechanistic pathways.[4] [5]

The second phase, ‘Type II translation,’ is the process by which discoveries and findings from phase I are adapted to create community or population based health promotion programs.[3] The transition from Type I to Type II translational research benefits from a multidisciplinary team comprised of behavioral scientists, clinical epidemiologists, clinicians, mixed-methods researchers, and biostatisticians.[3] Another important, yet often neglected component of the translational science research team, is the community partner.

Community partners understand the local and social-political context in which the research is being conducted.[6] In regard to health disparities research, community partners can serve as a voice for those who are most vulnerable. Community involvement early on in the process can help to ensure that the final product is culturally-tailored and responsive to community needs. Community involvement also helps to ensure the development and sustainability of programs and practice policies beyond the research study.[7, 8] Knowledge gained from these community programs can generate new theories that can be used in developing new interventions or refining existing ones, thus continuing the translational research cycle, or ‘reverse translation.’[9] Therefore, theory and community engagement play pivotal roles in the continuum of translational behavioral science research.

The Trial Using Motivational Interviewing and Positive Affect and Self-Affirmation in African-Americans with Hypertension(TRIUMPH) is a theoretically-based, randomized controlled trial targeting blood pressure control among adult African-Americans being treated for hypertension in community health centers and public hospitals located in New York City. This paper provides a detailed description of the theoretical framework and study design of TRIUMPH. It concludes with a critical reflection of the lessons learned in the process of implementing a health behavior intervention in a community-based setting and reinforces the value of community engagement.

2. Theoretical perspective

In preparation to design TRIUMPH, our team conducted a literature search to identify barriers and facilitators of medication adherence. This search was supplemented by our own qualitative data. [10] Barriers to medication adherence included inadequate knowledge of hypertension as well as misperceptions about the etiology and treatment of hypertension.[11–13] Patients often have misperceptions of hypertension such as associating it with only stress or expecting to feel physical symptoms.[10] These misperceptions may impact the pattern of medication usage. Moreover, patients may have unrealistic expectations when it comes to hypertension treatment and believe that medication is only to be taken for a short term.[13] The lack of confidence in one’s ability to take medications under less than optimal conditions has also been implicated as a contributor to poor adherence and was a recurring theme among patients we interviewed. [14, 15] We also identified factors which have been shown to facilitate medication adherence such as social support, trust in the provider-patient relationship, good doctor-patient communication as well as having access to culturally sensitive material and access to a home blood pressure monitoring device.[16, 17]

Guided by the behavioral scientist on the team we reviewed the most common theories on health behavior and discovered that some of the sentiments on adherence espoused by patients fit best within the framework of Social Cognitive theory(SCT). According to the Social Cognitive Theory, health behavior change is a function of one’s personal and external environment. [18, 19] Some of the constructs of SCT include ‘situation’ which describes the perceptions or misperception of factors that affect health behaviors and ‘behavioral capability’ which describes knowledge and skill that is necessary to perform a given behavior.

Self-efficacy is another construct of Social Cognitive theory that describes the confidence in one’s ability to take action to overcome barriers. It is a major cornerstone of health behavior change.[20] [21] The higher the self-efficacy for a task, the greater the likelihood that one will acquire the knowledge, skills, and reinforcements necessary to achieve a goal. Self-efficacy is also an important determinant of the expected outcomes. The higher a person’s self-efficacy, the more likely they are to attribute positive outcomes from their efforts, which reinforces their willingness to change their health behavior.[20] TRIUMPH applies three combined behavioral cognitive strategies positive affect, self-affirmation, and motivational interviewing to building self-efficacy which in turn, will impact health behaviors leading to blood pressure control. These strategies have been applied in basic social science research, but with few exceptions have not been used in clinical health behavior trials.[22]

Positive affect is a state of pleasurable engagement with the environment and reflects the extent to which a person feels enthusiastic, active, and alert.[23] Positive affect induction can be achieved by receiving unexpected compliments or by achieving success in completing small tasks.[24] Other methods for inducing positive affect include providing a small gift or directing patients to focus on previous positive events.[25, 26] [27–29] Positive affect may increase self-efficacy by increasing the desirability of the ultimate health behavior goal, the perceived link between the steps needed to accomplish this goal, and the belief that this effort will ultimately lead to the desired goal.[30]

Self-affirmation theory describes the motivation to preserve a positive image and self-integrity when self-identify is threatened. This theory has been applied to understanding how one may overcome negative expectations of their own ability and stay resolved to practice positive health behaviors.[31, 32] Self-affirmation can be induced through the active use of positive statements or memories about prior accomplishments. By enhancing the ability to overcome negative expectations and by drawing on previous experiences of success, self-affirmation may increase self-efficacy for health behavior change.[33]

Motivational interviewing is a directive, patient-centered counseling technique designed to motivate change by supporting self-efficacy and optimism for change. The goal is to facilitate patients to recognize and resolve the discrepancy between their present behavior and a desired future goal or outcome.[34, 35] The hypothesis for TRIUMPH was that the combined synergy of positive affect, self-affirmation, and motivational interviewing would lead to greater improvements in medication adherence and therefore a greater proportion of participants randomized to this group would achieve blood pressure control compared to patients randomized to a control group. Using a mixed methods approach, results from the qualitative data was then used inform the design of TRIUMPH.[36]

3. Design and Methods

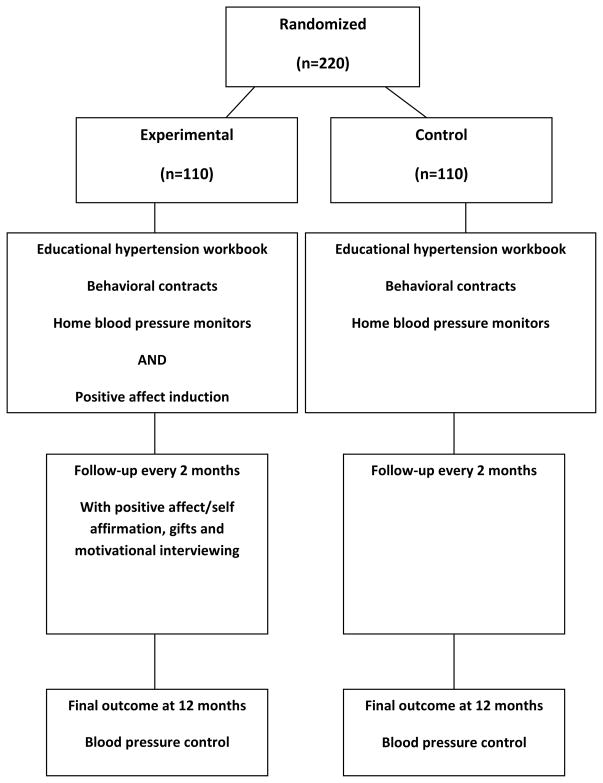

Figure 1 provides an overview of the study. Eligible participants were adults who self-identified themselves as African-American or Black, were age 21 or older, and had at least 2 documented readings of elevated blood pressures in the past 12 months despite being on medication. Blood pressure readings and medications were verified by research assistants using an electronic medical record system. Participants who met eligibility criteria, and who provided informed consent, were randomized to either an experimental or control arm. The experimental arm received the combined intervention of positive affect, self-affirmation, and motivational interviewing, whereas the control arm received an enhanced educational program in hypertension. All participants completed baseline assessments and were followed every two months via telephone for 10 months to deliver the intervention and to get their blood pressure readings. Participants met with a research assistant to complete the final closeout interview in person and received a $20 Visa gift card and $4.50 MetroCards (public transportation cards) for their participation.

Figure 1.

Diagram of TRIUMPH

3.1 Baseline Evaluation

Demographic assessments included age, country of origin, gender, marital status, education, employment status, type of occupation, and insurance. Clinical assessments included baseline objective blood pressure readings measured by trained research assistants which will be used for describing case-mix. The purpose was also to reinforce proper use of the blood pressure monitoring device. Blood pressure readings were taken by the research assistants using a BPTru automated monitor with the patient seated comfortably for five minutes prior to the measurements, following the AHA guidelines.[37] The same procedure will be followed at the 12-month follow-up visit. A description of the measures used in this study are provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Baseline questionnaires

| Charlson Comorbidity Index(CCI) | The CCI is a measure of comorbidity that takes into account both the number and severity of select comorbid conditions. [56] |

| Center for Epidemiologic Studies DepressionScale (CESD) | The CES-D scale is a reliable, and well-validated 20-item, self- report depression scale. [57] |

| Positive and Negative Affect Scale (PANAS): | The PANAS is a scale that consists of 2 components comprised of 10-items each that measure positive and negative affect. [58] |

| Medical Outcomes Social Support Scale (MOS) | The MOS support survey is a 20-item measure of emotional, informational, tangible, affectionate support, and positive social interaction.[59] |

| Perceived Stress Scale(PSS) | The PSS is a 10-item scale that measures the degree to which situations are appraised as stressful. [60] |

| Morisky Medication adherence | The Morisky scale is a 4-item widely used and well-validated scale that specifically addresses adherence to prescribed medication regimen.[53] |

| Medication Adherence Self-Efficacy Scale(MASES) | The MASES is a 26-item self-efficacy scale that measures adherence to medications under stress conditions.[14] |

| Physical Activity Recall interview (PAR). | The PAR estimates total daily energy expenditure by asking participants to estimate the number of hours spent in moderate, hard, and very hard activities during the previous seven days.[61] |

3.2 Control Group

The educational/behavioral contract group (control group) received a hypertension workbook and follow-up telephone calls every two months. The duration of each call was on average 30–40 minutes. During these calls participants were asked to describe any interim events such as emergency room visits, any changes in medications, any adverse events, and to report their last blood pressure reading. They did not receive the positive affect/self-affirmation induction or motivational interview intervention. The workbook was specifically developed to assist African-American patients with hypertension improve blood pressure management.[38] This workbook addressed those factors that had been described as being barriers to medication adherence. It provided basic knowledge about hypertension, addressed some commonly held misperceptions about hypertension, and provided a more realistic expectation of living with hypertension. It included activities that supported adherence such as goal-setting and a behavioral contracting exercise in which participants were asked to write what they are willing to commit to do (e.g., take their diuretic), when they will do it (e.g., in the morning), and how often they are willing to do it (e.g., once a day).[38] The research assistant encouraged participants to describe their goals for medication adherence and steps they were taking in order to achieve this goal. The research assistant did not make recommendations but listened and documented what the patient stated.

3.3 Experimental Group

The TRIUMPH experimental group received the following intervention components via telephone: 1) positive-affect induction, 2) self-affirmation intervention, and 3) motivational interviewing. All 3 elements were delivered at baseline and then every 2 months for 10 months. The intervention was delivered via telephone by two research assistants who received training on how to implement intervention components. Each session took on average 30–40 minutes to complete. The strategies were delivered sequentially. First participants were asked to think of things that made them feel good as a strategy for inducing positive affect. They were then prompted to think about proud moments as a self-affirmation exercise. They were also asked to describe how confident they were in their ability to take their medications daily and then taken through the motivational interviewing exercise to enhance self-efficacy and build intrinsic motivation to taking their medications daily. They were asked to come up with their own strategies to help them to take their medications daily. Participants were asked to participate in these reflective exercises daily. There is also a reflection on previous conversations. The intention was for participants to integrate these routines into their daily activities. The same procedure was done at each call.

3.3.1 Positive Affect Induction Component of the Intervention

The work of Isen et al. was used to frame the positive affect intervention protocol. [39–42] Details of the protocol and scripts have been described in previous manuscripts.[22] Participants were provided with the following scenario: “When people have positive feelings, it helps them overcome challenges in their lives, including health challenges, like taking their prescribed hypertension medication regularly. One very simple way to stay positive is to think about the small things in your life that make you feel good or things that bring a smile to your face. Participants were then posed the question: “What are some small things that make you have positive feelings or things that make you feel good, even for just a few moments?” Participants were then told to think about things that invoke positive feelings and discussed this with the research assistant. Participants in this arm received either a $20 Metrocard or a $20 Target Gift card as an additive affect induction strategy in the mail. Participants were not told that they were going to receive items in the mail.

3.3.2 Self-affirmation induction

The technique for self-affirmation was based on the work of Steel.[31] Participants were asked to think about proud moments using the following script. “In addition to things that make you feel good, when people think of some proud moments in their lives or things they have done that they are proud of, it also helps them overcome challenges. What are some moments in your life or things that you have done that you will always be proud of?

3.3.3 Motivational Interviewing

The motivational interviewing components of TRIUMPH were based on the work of Miller and Rollnick.[43] TRIUMPH included the following steps: 1) an assessment of the participant’s motivation and confidence in engaging in medication adherence; 2) eliciting barriers and concerns about their medication adherence; 3) summarization in a non-threatening manner of the ‘pros’ and ‘cons’ of any concerns; 4) a menu of options to improving medication adherence was provided such as taking medications at the same time, using a medication dispenser, or using their mobile phone applications as an alarm clock or reminder to take medications; and 5) an assessment of their values and goals, in order to help the patient link their current health behavior pattern to their core values and life goals.

3.4 Outcomes

Upon completion of the study, the primary outcome for TRIUMPH will be blood pressure control based on JNC 7.[44] Based on the Seventh Joint National Committee on Detection, Evaluation and Treatment of Hypertension (JNC-7) criteria,[45] controlled HTN is defined as average systolic blood pressure (SBP) < 140 mm Hg or diastolic blood pressure (DBP) < 90 mmHg (for those without comorbidity); or average clinic SBP < 130 mm Hg or DBP < 80 mm hg (for those with diabetes or kidney disease).[44]

4. Sample size estimation

Parameters for sample size calculation included a power of 80% and a standard test level of 0.05. Based on our pilot data, it is expected that 57% in the intervention group will achieve target blood pressure control compared to 39% in the control. Therefore, 85 patients per group, or 190 overall, are required. A conservative loss to follow-up rate of 15% was predicted resulting in a sample size of 220 participants.

4.1 Baseline demographic characteristics

All 220 participants have been recruited and randomized. There were no demographic differences by randomization groups. The average age was 56 +9.9. There was a greater proportion of women in the study 68%, which may reflect barriers for African-American men to seek care in medical settings.[46, 47] As per the study requirements, all of the participants were African-American, with 9% describing themselves as both Hispanic and African-American. In this cohort, 21% were married, 80% were not employed, 26% did not have health insurance, and approximately 28% completed high school. A total of 37% of the population was born outside of the US. The study did not inquire about documentation or immigration status. Several participants questioned whether participation in the study would impact their immigration status, thus highlighting the importance of working with community partners to establish a trusting relationship. This population also had a high rate of comorbidity with 42% of the population with diabetes and almost 20% with a prior stroke. Of note, over 50% of participants said that they did not know of the impact of hypertension on their heart, kidneys, or brain and requested more information. The low socioeconomic resources coupled with high comorbidity made subjects in this study particularly vulnerable to poor outcomes.

We are in the process of following participants. Once data collection and final interviews are complete, a two sample proportion comparison will be used to statistically examine whether the intervention that combines positive affect and self-affirmation with motivational interviewing improves blood pressure control more than an educational/behavioral contract group at 12 months.

5. Discussion

TRIUMPH is a randomized trial targeting blood pressure control among African-Americans with hypertension to test the impact of combined approaches on behavioral change. The approach used in this study is similar to what was used by Ogedegbe et al. [48]. However, TRIUMPH, differs from the previous study in three respects, setting, approach, and primary outcome. TRIUMPH is more of a pragmatic study conducted in a community-practiced based setting. TRIUMPH more fully incorporated motivational interviewing techniques in the protocol in addition to positive affect and self-affirmation. Lastly, the primary outcome in TRIUMPH is blood pressure control and not medication adherence as in the previous study. TRIUMPH also applied more of participatory research approach.

The implementation of TRIUMPH was done in collaboration with members of the Lincoln Center for Community Collaborative Research (LCCCR), a network of community based organizations, community residents, and physicians from the South Bronx and Harlem who are dedicated to reducing and eliminating health disparities in communities of color through outreach, education, and community-driven research. Our community partners were pivotal in developing recruitment strategies, finding solutions to methodological problems, and reconciling differences between researchers and potential participants.

An important lesson learned was that community partners needed evidence demonstrating that academic researchers had a genuine interest in the community as people and “not just as research subjects”. The LCCCR also stressed the importance of regular and sustained meetings between the academic researchers and the physicians and staff at the recruitment sites. Therefore, we participated in several non-study related community activities such as workshops on community-based participatory research methods and health outreach activities such as blood pressure and diabetes screenings. The goal of these activities is to enhance the communities’ awareness of hypertension and associated comorbid conditions and increase the capacity to conduct their own research. These initiatives also helped to reinforce that our interest was not merely on recruiting research subjects but that there was a true commitment to building mutually beneficial community-academic relationships. Community partners also wanted to collaborate on research projects that they deemed as being important and on which they served as principal investigators or the lead institutions. They helped to establish a co-learning model that is inherent in the principles of community-based participatory research. [49]They participated in teaching medical students at our institution and we participated in teaching their residents in research methodology. The community partners were also instrumental in identifying best practices for participant recruitment in each setting such as optimal locations for recruitment and suggestions for participant incentives.

There are limitations to TRIUMPH that may impact generalization such as the lower proportion of men relative to women. This problem is common to primary care practices and may reflect the reluctance for men, in particular racial and ethnic minority men to seek care. A report by the CommonWealth Fund highlights this fact that men are less likely to receive preventive health care services and are more disconnected from the health system than women. [50]Future studies conducted in non-traditional venues such as barbershops are needed to address this barrier to recruitment of men.[51]

Another limitation is the use of a self-reported adherence measurement rather than an objective measure such as pill bottles which can be biased by inaccurate patient recall or by the influence of social desirability. While one would expect the same level of bias across both the experimental and control group, this potential for bias is important to note in interpreting our data.

The strategies incorporated in TRIUMPH have been shown to increase self-efficacy. However, future studies are needed to provide empirical evidence of its ability to support long-term health behavior maintenance. Future implementations of this study would benefit from direct application of additional theoretical perspectives in order to assess the mediators of behavior change and the impact of TRIUMPH on long-term maintenance. [52, 53] An example is provided by Self-Determination Theory(SDT) which posits that in order for health behavior maintenance to occur, there must be an internalization process that aligns behaviors with one’s values.[54] Incorporating strategies to support autonomy, competency, and a sense of relatedness are important elements that need to be considered to achieve internalization of health behavior change. [55]

TRIUMPH provides a model for incorporating the translational science research paradigm to conducting pragmatic behavioral science trials in a real-world setting among a vulnerable population. Our experience and lessons learned from interactions with our community partners reinforced the value of community engagement in developing and implementing interventions. If proven effective, this study will provide a model for low cost, community-based interventions for medication adherence and blood pressure control.

Acknowledgments

Funding: Center for Excellence in Health Disparities Research and Community Engagement (CEDREC) NIMHD P60 MD003421-02

We are deeply grateful to Dr. Alice Isen for her pioneering work on positive affect.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Rosamond W, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics--2008 update: a report from the American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Circulation. 2008;117(4):e25–146. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.187998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bosworth HB, et al. Racial differences in blood pressure control: potential explanatory factors. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(5):692–8. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0547-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Woolf SH. The meaning of translational research and why it matters. JAMA. 2008;299(2):211–3. doi: 10.1001/jama.2007.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Glanz K, Bishop DB. The role of behavioral science theory in development and implementation of public health interventions. Annu Rev Public Health. 2010;31:399–418. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.012809.103604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rohrbach LA, et al. Type II translation: transporting prevention interventions from research to real-world settings. Eval Health Prof. 2006;29(3):302–33. doi: 10.1177/0163278706290408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Benoit C, et al. Community-academic research on hard-to-reach populations: benefits and challenges. Qual Health Res. 2005;15(2):263–82. doi: 10.1177/1049732304267752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kilbourne AM, et al. Advancing health disparities research within the health care system: a conceptual framework. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(12):2113–21. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.077628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wallerstein NB, Duran B. Using community-based participatory research to address health disparities. Health Promot Pract. 2006;7(3):312–23. doi: 10.1177/1524839906289376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sipido KR, et al. Identifying needs and opportunities for advancing translational research in cardiovascular disease. Cardiovasc Res. 2009;83(3):425–35. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvp165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boutin-Foster C, et al. Ascribing meaning to hypertension: a qualitative study among African Americans with uncontrolled hypertension. Ethn Dis. 2007;17(1):29–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ogedegbe G, et al. Barriers and facilitators of medication adherence in hypertensive African Americans: a qualitative study. Ethn Dis. 2004;14(1):3–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ogedegbe G, et al. Reasons patients do or do not take their blood pressure medications. Ethn Dis. 2004;14(1):158. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ogedegbe G, Mancuso CA, Allegrante JP. Expectations of blood pressure management in hypertensive African-American patients: a qualitative study. J Natl Med Assoc. 2004;96(4):442–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ogedegbe G, et al. Development and evaluation of a medication adherence self-efficacy scale in hypertensive African-American patients. J Clin Epidemiol. 2003;56(6):520–9. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(03)00053-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schoenthaler A, Ogedegbe G, Allegrante JP. Self-efficacy mediates the relationship between depressive symptoms and medication adherence among hypertensive African Americans. Health Educ Behav. 2009;36(1):127–37. doi: 10.1177/1090198107309459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pickering TG. Home blood pressure monitoring: a new standard method for monitoring hypertension control in treated patients. Nat Clin Pract Cardiovasc Med. 2008;5(12):762–3. doi: 10.1038/ncpcardio1374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Odedosu T, et al. Overcoming barriers to hypertension control in African Americans. Cleve Clin J Med. 2012;79(1):46–56. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.79a.11068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bandura A. Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol Rev. 1977;84(2):134–139. doi: 10.1037//0033-295x.84.2.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Glanz K, Lewis FM, Rimer BK. Health behavior and health education : theory, research, and practice. 2. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 1997. pp. 113–138. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bandura A. Health promotion by social cognitive means. Health Educ Behav. 2004;31(2):143–64. doi: 10.1177/1090198104263660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Strecher VJ, et al. The role of self-efficacy in achieving health behavior change. Health Educ Q. 1986;13(1):73–92. doi: 10.1177/109019818601300108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Charlson ME, et al. Randomized controlled trials of positive affect and self-affirmation to facilitate healthy behaviors in patients with cardiopulmonary diseases: rationale, trial design, and methods. Contemp Clin Trials. 2007;28(6):748–62. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2007.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pressman SD, Cohen S. Does positive affect influence health? Psychol Bull. 2005;131(6):925–71. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.131.6.925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Isen AM. Positive Affect as a Source of Human Strength. In: Aspinwall, Staudinger U, editors. A Psychology of Human Strengths. The American Psychological Association; Washington, D.C: 2003. pp. 179–195. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fredman L, et al. Elderly patients with hip fracture with positive affect have better functional recovery over 2 years. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54(7):1074–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00786.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Appel LJ, et al. Effects of comprehensive lifestyle modification on blood pressure control: main results of the PREMIER clinical trial. JAMA. 2003;289(16):2083–93. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.16.2083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kelsey KS, et al. Positive affect, exercise and self-reported health in blue-collar women. Am J Health Behav. 2006;30(2):199–207. doi: 10.5555/ajhb.2006.30.2.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tsenkova VK, et al. Coping and positive affect predict longitudinal change in glycosylated hemoglobin. Health Psychol. 2008;27(2 Suppl):S163–71. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.27.2(Suppl.).S163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ostir GV, Ottenbacher KJ, Markides KS. Onset of frailty in older adults and the protective role of positive affect. Psychol Aging. 2004;19(3):402–8. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.19.3.402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Erez A, Isen AM. The influence of positive affect on the components of expectancy motivation. J Appl Psychol. 2002;87(6):1055–67. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.87.6.1055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Steele CM, Spencer SJ, Lynch M. Self-image resilience and dissonance: the role of affirmational resources. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1993;64(6):885–96. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.64.6.885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sherman DAK, Enlson LD, Steele CD. Do messages about health risks threaten the self? Increasing the acceptance of threatening health messages via self affirmation. Personality and Social Psychology Bulleting\ 2000;26:1046–1058. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Steele CM. A threat in the air: how stereotypes shape intellectual identity and performance. Am Psychol. 1997;52:613–629. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.52.6.613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Miller W, Rollnick S. Motivational Interviewing: Preparing people for change. New York: Guilford press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rollnick S, Miller W. What is Motivational Interviewing? Behavioral and cognitive psychotherapy. 1995;23:325–334. doi: 10.1017/S1352465809005128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Peterson JC, et al. Translating Basic Behavioral and Social Science Research to Clinical Application: The EVOLVE Mixed Methods Approach. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2012 doi: 10.1037/a0029909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Perloff D, et al. Human blood pressure determination by sphygmomanometry. Circulation. 1993;88(5 Pt 1):2460–70. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.88.5.2460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Boutin-Foster C, et al. Applying qualitative methods in developing a culturally tailored workbook for black patients with hypertension. Patient Educ Couns. 2009;77(1):144–7. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2009.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Isen AM, Rosenzweig AS, Young MJ. The influence of positive affect on clinical problem solving. Med Decis Making. 1991;11(3):221–7. doi: 10.1177/0272989X9101100313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Isen AM, Nygren TE, Ashby FG. Influence of positive affect on the subjective utility of gains and losses: it is just not worth the risk. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1988;55(5):710–7. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.55.5.710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Isen AM, Daubman KA, Nowicki GP. Positive affect facilitates creative problem solving. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1987;52(6):1122–31. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.52.6.1122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Isen AM, et al. The influence of positive affect on the unusualness of word associations. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1985;48(6):1413–26. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.48.6.1413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rollnick S, MW What is motivational interviewing? Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy. 1995;23:325–334. doi: 10.1017/S1352465809005128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chobanian AV, et al. The Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure: the JNC 7 report. Jama. 2003;289(19):2560–72. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.19.2560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chobanian AV, et al. Seventh report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. Hypertension. 2003;42(6):1206–52. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000107251.49515.c2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lucas JW, Barr-Anderson DJ, Kington RS. Health status, health insurance, and health care utilization patterns of immigrant Black men. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(10):1740–7. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.10.1740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cheatham CT, Barksdale DJ, Rodgers SG. Barriers to health care and health-seeking behaviors faced by Black men. J Am Acad Nurse Pract. 2008;20(11):555–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7599.2008.00359.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ogedegbe GO, et al. A randomized controlled trial of positive-affect intervention and medication adherence in hypertensive African Americans. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(4):322–6. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.1307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Israel BA, et al. Review of community-based research: assessing partnership approaches to improve public health. Annu Rev Public Health. 1998;19:173–202. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.19.1.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sandman D, Simantov E, An C. Out of Touch: American Men and the Health Care System Commonwealth Fund Men’s and Women’s Health Survey Findings. Commonwealth Fund; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yancy CW. A bald fade and a BP check: Comment on “Effectiveness of a barbershop-based intervention for improving hypertension control in black men”. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(4):350–2. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Morisky DE, et al. Predictive validity of a medication adherence measure in an outpatient setting. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 2008;10(5):348–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7176.2008.07572.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 53.Morisky DE, Green LW, Levine DM. Concurrent and predictive validity of a self-reported measure of medication adherence. Med Care. 1986;24(1):67–74. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198601000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ryan RM, Deci EL. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am Psychol. 2000;55(1):68–78. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.55.1.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Williams GC, Niemiec CP. Positive affect and self-affirmation are beneficial, but do they facilitate maintenance of health-behavior change? A self-determination theory perspective: comment on “a randomized controlled trial of positive-affect intervention and medication adherence in hypertensive African Americans”. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(4):327–8. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.1830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Charlson ME, et al. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(5):373–83. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale: A Self-Report Depression Scale for Research in the General Population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1(3):385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Watson D, Clark LA, Tellegen A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: the PANAS scales. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1988;54(6):1063–70. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.54.6.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sherbourne CD, Stewart AL. The MOS social support survey. Soc Sci Med. 1991;32(6):705–14. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(91)90150-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav. 1983;24(4):385–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Pereira MA, et al. A collection of Physical Activity Questionnaires for health-related research. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1997;29(6 Suppl):S1–205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]