Abstract

Background: The use of corticosteroid in the management of severe acute pancreatitis (SAP) remains contentious and is still being debated despite many pre-clinical studies demonstrating benefits. The limitations of clinical research on corticosteroid in SAP are disparities with regard to benefit, a lack of adequate safety data and insufficient understanding of its mechanisms of action. Thus, we performed a meta-analysis to assess the effectiveness of corticosteroid in experimental SAP and take a closer look at the relation between the animal studies and prospective trials. Methods: Studies investigating corticosteroid use in rodent animal models of SAP were identified by searching multiple three electronic databases through October 2013, and by reviewing references lists of obtained articles. Data on mortality, changes of ascitic fluid and histopathology of pancreas were extracted. A random-effects model was used to compute the pooled efficacy. Publication bias and sensitivity analysis were also performed. Results: We identified 15 published papers which met our inclusion criteria. Corticosteroid prolonged survival by a factor of 0.35 (95% CI 0.21-0.59). Prophylactic use of corticosteroid showed efficacy with regards to ascitic fluid and histopathology of pancreas, whereas therapeutic use did not. Efficacy was higher in large dose and dexamethasone groups. Study characteristics, namely type of steroids, rout of delivery, genders and strains of animal, accounted for a significant proportion of between-study heterogeneity. No significant publication bias was observed. Conclusions: On the whole, corticosteroids have showed beneficial effects in rodent animal models of SAP. Prophylactic use of corticosteroid has failed to validate usefulness in prophylaxis of postendoscopic retrogradcholangiopancreatography pancreatitis. Further appropriate and informative animal experiments should be performed before conducting clinical trials investigating therapeutic use in SAP.

Keywords: Glucocorticoids, acute pancreatitis, animals studies, meta-analysis

Introduction

Acute pancreatitis (AP) is a common clinical condition with variable severity in which some patients experience mild, self-limited attacks while others manifest a severe, highly morbid, and frequently lethal attack [1,2]. The exact mechanisms by which diverse etiological factors induce an attack are still unclear, while it is generally believed that the release of a variety of inflammatory mediators causes a cascade-like reaction and leads to systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS). An excessive SIRS leads to distant organ damage and multiple organ dysfunction syndrome (MODS), which established the role played by inflammatory mediators in the aggravation of AP and the resultant fatal condition [3-5].

Glucocorticoids have well-known immunosuppressive effects and were commonly believed to be involved in the regulation of cytokine production and the inflammatory processes [6]. Furthermore, glucocorticoids protected the acinar cells, stabilized the cell membrane, and directly regulated amylase synthesis [7,8]. Some earlier studies supported the beneficial effects of the prophylactic or therapeutic use of glucocorticoids with regard to hemodynamic changes, pancreatic edema formation, histological changes in the pancreas, and even survival [9-11], but others cast doubt on the favorable effects and by contrast, showed the exacerbation of pancreatitis by the administration of glucocorticoids [12-14]. In addition, the possible involvement of steroids in the pathogenesis of acute pancreatitis and considerable side-effects have long been a drawback in the use of this agent in pancreatitis [15,16]. Therefore, whether or not glucocorticoids are an effective medicine for pancreatitis is a matter of much dispute. Clinically, well-designed controlled prospective studies have been performed to evaluate the effects of corticosteroid use in prevention of AP after diagnostic or therapeutic endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), by which the designs were compatible to the idea of prophylactic use in animal studies [17-19]. However, the clinical utilization of corticosteroid in pancreatitis has always been controversial and clinical trial for therapeutic purposes in severe acute pancreatitis (SAP) patients with is still scarce due to disparities with regard to beneficial effects and risks, a lack of adequate safety data and insufficient understanding of its mechanisms of action.

Meta-analyses of data from human studies are invaluable resources in the life sciences. Similarly there are a number of benefits in conducting systematic reviews, especially meta-analysis on data from animal studies. They can be used to inform clinical trial design, highlight areas which may benefit from further preclinical research, judge the safety and efficacy of drugs/treatments or provide insights into discrepancies between preclinical and clinical trial results [20,21]. For discovering the molecular mechanisms underlying AP, rodent models essentially contribute to the understanding of the pathological reaction and are thus often used in assessment of drug efficiency in preclinical research of SAP [22]. Therefore, in this paper, we performed a meta-analysis of the use of corticosteroid in rodent animal models of experimental SAP. The objectives of the present study were to: (1) collate the experimental evidence for glucocorticoids administered before or after on set SAP in rodent animal models and explore whether the contradictory results in animal studies arose from differences in the dose and type of steroids and experimental models et al. (2) assess whether combined results of prophylactic use of corticosteroids in animal studies could revealed indications found in clinical studies; (3) propose the development of further preclinical hypotheses to test in animals and ultimately aid in the design of future clinical trials.

Materials and methods

Search strategy

The following electronic databases were searched for original articles concerning the effects of glucocorticoids on experimental SAP published up to October 2013: PubMed, Embase and Web of Knowledge. The following key words were used to identify possible publications: “glucocorticoids” or “glucocorticoid” or “corticosteroids” or “corticosteroid” or “steroids” or “steroid” or “hydrocortisone” or “hydrocortisone sodium succinate” or “cortisone” or “prednisone” or “prednisone acetate” or “prednisolone” or “prednisolone acetate” or “methylprednisone” or “6alpha-methylprednisolone sodium succinate” or “dexamethasone” or “dexamethasone sodium phosphate” or “betamethasone” or “betamethasone sodium phosphate” and “pancreatitis” or “pancreatitides” or “pancreas” or “pancreatic inflammation”. Search results were limited to animal subjects. No language restriction was used. In addition, we searched for possible eligible studies in the references within the retrieved articles, as well as in review articles.

Criteria for inclusion and exclusion

The selection of studies was performed on the basis of the title and abstract. Two well trained investigators (M.Y. and Z.Y.) independently screened all the abstracts for the inclusion criteria. Differences were resolved by a third investigator (Y.Z.). Studies were included if they fulfilled the following criteria: (1) reported quantitative estimates of the effects of glucocorticoids on mortality, change of volume of ascites and histopathology of pancreas in experimental SAP; (2) number of animals per group was given. Papers were excluded if they fulfilled one of the following criteria: (1) animal studies performed in non-rodent species such as dogs, pigs; (2) Glucocorticoid treatment was combined with co-treatments; (3) glucocorticoid treatment was longer than 5days; (4) studies were specially excluded where in vitro or edematous pancreatitis models were used; (5) double publication or data republication. If duplicate article was published using the same case series, the data from the most informative manuscript was included.

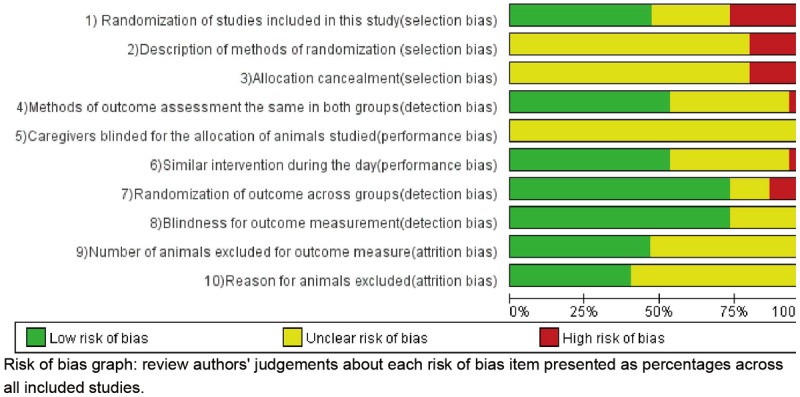

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two reviewers (M.Y. and Z.Y.) independently assessed the associated risk of bias using the 10 criteria (rating: yes, no, unclear) adjusted from recommendation by the Cochrane Back Review Group [23]. When necessary, discrepancies were rechecked with a third reviewer (Y.Z.) and consensus achieved by discussion. The items in the criteria were described in Figure 2, basing on the possible presence of selection bias (items 1, 2 and 3), performance bias (items 5 and 6), detection bias (items 4, 7 and 8) and attrition bias (items 9 and 10) [24]. The “green” indicated low risk of bias, the “red” indicated high risk of bias, “yellow” indicated unknown risk of bias. Studies that met 5 of the 10 criteria and had no serious flaw (such as drop-out rate higher than 30% due to inappropriate manipulation) were rated as having low risk of bias.

Figure 2.

Risk of bias, averaged per item.

Data extraction and data synthesis

From the studies included, the following data were extracted: first author’s last name, year, animals’ genders, species and strains, number of animals per group, method of AP induction, type and dose of glucocorticoids, timing of glucocorticoids administration relative to AP induction, route of administration, timing data collection and outcome measures. The patient-important mortality (primary) and surrogate parameters including changes in the volume of ascites and histopathology of pancreas (secondary) were used to measure the efficacy of glucocorticoids. Data were processed as following: for mortality, the Risk Ratio was determined; for the outcome measure “volume of ascites” and “histopathology of the pancreas”, the standardized mean difference (SMD) was calculated. Where a publication reported more than one experiment, we considered these to be independent experiments and extracted data for each of these [25]. When a single control group was used for multiple treatment groups this was adjusted by dividing by the number of treatment groups served (surrogate parameters) [24]. In case histopathological data was not presented in an overall score, we calculated an overall score by uniformly weighing the separate means and SE’s of fibrosis, acinar cell loss etc. For mortality, we merge the events and sample sizes of the treatment group into one group, the same for the control group [24]. If data were not reported, attempts were made to contact the authors for additional information. Where data were only presented graphically, we used digital ruler software (GetData software) to extract.

Statistical analysis

Taking into account both within-study and between-study variabilities, we used the random effects model of inverse variance method which is more conservative than fixed-effects to aggregate data (either OR or SMD) and obtain an overall effect size and 95% confidence interval [26]. Heterogeneity across studies was assessed by performing X2 tests (assessing the P value) and calculating I2 statistic, a quantitative measure of inconsistency across studies. Studies with an I2 of 25% to 50% were considered to have low heterogeneity, I2 of 50% to 75% was considered moderate heterogeneity, and I2 > 75% was considered high heterogeneity. If I2 > 50%, potential sources of heterogeneity were identified by sensitivity analyses conducted by omitting one study in each turn and investigating the influence of a single study on the overall pooled estimate [27].

To explore the impact of study characteristics on estimates of effect size, we performed a stratified meta-analysis with experiments grouped according to the following: timing of corticosteroid treatment (prophylactic or therapeutic), equivalent dosage of dexamethasone. Given consideration of different type of steroids, we used equivalent dosage of dexamethasone to evaluate the impact of dose, using a conversion rate as fowling: hydrocortisone 20 mg = cortisone 25 mg = prednisone or prednisolone 5 mg = methylprednisolone 4 mg = dexamethasone 0.75 mg; subsequently we converted these continuous variable into semi-quantitative data: low dose (< 0.5 mg/kg), moderate dose (0.5-1 mg/kg) and large dose (> 1 mg/kg). Additionally, for outcomes with 10 or more experiments included, we further find the source of heterogeneity according to the following: method of AP induction, type of steroids, route of drug delivery, time for outcome measurement, strain and gender of animals used. Publication bias was examined by Egger’s test [28]. Trim and fill analysis was performed to yield an effect of adjusted for funnel plot asymmetry. All of the calculations were conducted by STATA version 12.0 (Stata Corporation, College Station, TX, USA). P values were 2-sided and P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Description of the included studies

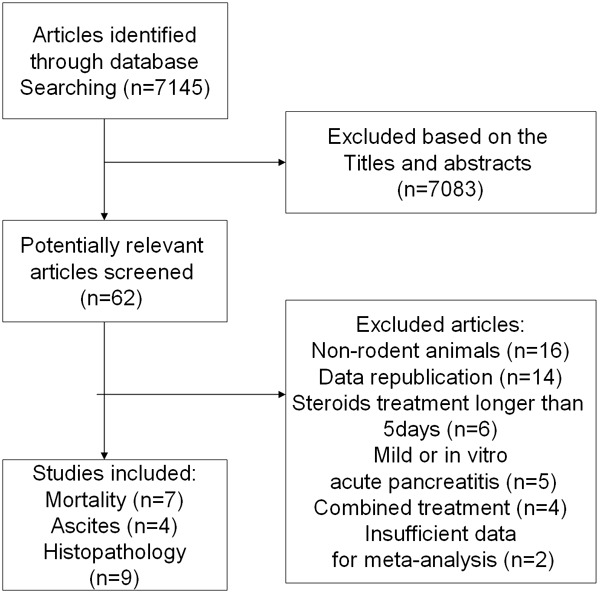

Based on our search criteria, we identified 7145 articles from PubMed, EMBASE and Web of Knowledge or by hand-searching. According to the search strategy described above mentioned, we retrieved 62 papers that seemed to meet our selection criteria. After studying the full-text articles, 47 were excluded, among which 16 were excluded for non-rodent animals used, 14 for data republication, 6 for long-term corticosteroid treatment (> 5 days), 5 for mild or in-vitro AP models, 4 for co-treatments, 2 for unavailable quantitative data. Finally, a total of fifteen articles with approximately 500 animals were included in this meta-analysis [29-43] (Figure 1). The study characteristics varied considerably between the included papers (Table 1). Male rat models (Wistar, Sprague-Dawley) [29-31,33,35,36,38-40] were used in most of the 15 studies, and female gender rats were used in 3 studies [32,34,43], while the gender of remaining studies were not mentioned [37,41,42]. Most studies used rats [29-40,42,43] and one performed in rabbits [41]. Nine different techniques were used to induce AP. Within these, most studies induce AP through retrograde infusion of sodium taurocholate into bile pancreatic duct [31-38]; 2 studies by retrograde infusion of chenodeoxycholic superimposed on cerulean (iv) or litigation of pancreatic duct [29,42]; 2 by bile-pancreatic duct obstruction (12 h) or closed duodenal loop [30,39]; 1 study via purely infusion of glycodeoxycholic acid [41]; 1 by retrograde infusion of trypsin (id) [43], and the remaining one used L-arginine (ip) [40]. Also the administration time and delivery routes, the dosage and the type of steroids varied greatly between the studies. Seven studies reported mortality, four including 9 experiments presented volume of ascitic fluids and nine studied histopathology of pancreas could be pooled in the final analysis (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Identification of eligible studies from different databases.

Table 1.

Main characteristics of included studies

| Study | Species | N (c)/n (exp) | Method AP induction | Type and timing of GC | Duration and dose of GC | Admin rout | Timing data collection | Outcome measures |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thomas et al, 1998 | male; Rats/sprague-dawley | 10/32 | Cerulean (30 ug/kg iv) superimposed on 10 mM glycodeoxy-cholic acid (id) | Pred; 6 h after AP induction | 2 mg/kg·d; 10 mg/kg·d; 50 mg/kg/d | Iv | 36 h | Mortality; ascites; histological score |

| Ramudo et al, 2010 | Male; rats/wistar | 4/8 | Bile-pancreatic duct obstruction (BPDO) for 12 h | Dx, 30 min before and 1 h after AP | 1 mg/kg | Im | 12 h | Histological score |

| Ramudo et al, 2010 | Male; rats/wistar | 8/16 | Retrograde infusion of 3.5% sodium taurocholate (id) | Dx, 30 min before and 1 h after AP | 1 mg/kg | Im | 3 h, 6 h | Histological score |

| Gloor et al, 2001 | Female; rats/wistar | 8/21 | Retrograde infusion of 5% sodium taurocholate (id) | Hc; 10 min after AP induction | 10 mg/kg | Iv | 1.5 h, 3 h, 6 h, 12 h, 24 h; 72 h | Mortality |

| Zhang et al, 2007 | Male; rats/SD | 45/45 | 5% sodium taurocholate (1 mg/kg id) | Dx; 15 min after AP induction | 5 mg/kg | Iv | 3 h, 6 h, 12 h | Mortallity; histological score |

| Muller et al, 2008 | Female; rats/Wistar | 6/6 | Retrograde infusion of 5% sodium tauro-cholate (1 mg/kg id) | Dx; 1 h prior ro AP induction | 1 mg/kg | Im | 6 h | Mortallity |

| Wang et al, 2003 | Male; rats/wistar | 18/18 | Retrograde infusion of 5% sodium taurocholate (id) | Dx; 5 min after AP induction | 0.5 mg/kg | Iv | 12 h | Mortallity; histological score |

| Ou et al, 2012 | male; rats/SD | 36/36 | Retrograde infusion of 3.5% sodium taurocholate (id) | Dx; 15 min after AP | 5 mg/kg | Iv | 3 h; 6 h; 12 h | Mortality |

| Kandil et al, 2006 | unknown; rats/SD | 8/8 | Retrograde infusion of 40 g/L sodium taurocholate (id) | Dx; 4 d before AP induction | 2 mg/kg (per day), continued for 4 days | Ip | 24 h | Histological score |

| Paszt et al, 2004 | Male; rats/Wistar | 12/24 | Retrograde infusion of sodium taurocholate (id) | Dx or hydrocortisone; just porior to AP induction | 4 mg/kg; 20 mg/kg | Sc | 24 h | Mortality |

| Richter et al, 1994 | Female; rats/Wistar | 6/6 | Retrograde infusion of trypsin (id) | Pre; 1 h before AP induction | 3 mg/kg | Iv | 6 h, 24 h, 48 h | Histological score |

| Takaoka et al, 2002 | Male; rats/Wistar | 3/27 | Closed duodenal loop induced pancreatitis group (CDL) | Mp; 5 min just before the preparation of CDL | 30 mg/kg | Iv | 6 h | Ascites; histological score |

| Paszt et al, 2008 | Male; rats/Wistar | 6/6 | Administration of L-arginine (ip) | Mp; just before the induction of AP | 30 mg/kg | Sc | 24 h | Histological score |

| Osman et al, 1999 | Mixed; rabbits/New Zealand White | 7/10 | Chenodeoxycholic bile acid (id) | Hc; 30 min before AP induction | 50 mg/kg | Sc+iv | 12 h | Mortality; acsites |

| Sun et al, 2007 | unknown; rats/SD | 20/20 | 5% chenodeoxycholic bile acid (2 mg/kg id) and litigation of pancreatic duct | Hc; 30 min before AP induction | 10 mg/kg | Sc+iv | 1 h, 3 h, 6 h, 12 h | Ascites; histological score |

Abbreviation: SD: sprague-dawley; id: intraductal; ip: intraperitoneal; iv: intravenous; Sc: subcutaneous; Dx: dexamethasone; Hc: hydrocortisone; Pre: prednisone; Pred: prednisolone; Mp: methylprednisone; AP: acute pancreatitis.

Quality of reporting and risk of bias

Figure 2 showed the overall results of the risk of bias assessment of the 15 studies included in this meta-analysis. 73% of the studies stated that the allocation of the experimental units to the treatment groups was randomized. However, none of these studies mentioned the method of randomization used and only one provided sufficient details so that the adequacy of the method could be judged. None of the papers described whether or not the allocation to the different groups during the randomization process was concealed. 53% of the studies reported that they blinded the outcome assessment. Figure 2 showed that only four out of the 15 studies scored 5 out of the 10 items as low risk of bias. Many items were scored as “unclear risk of bias”, but few studies were deemed fatally flawed, indicating reliability of our results to some extent.

Effects of glucocorticoids

Mortality

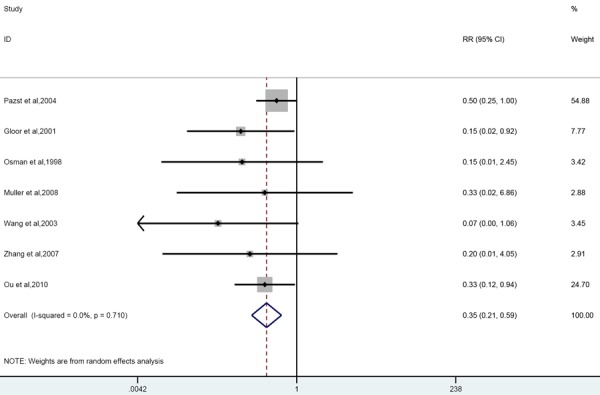

Seven publications studied the effect of glucocorticoids administration on mortality in experimental SAP. A combination of all the animal studies included showed a significant effect on reduced mortality (RR 0.35 [0.21, 0.59]; n = 7). No significant heterogeneity was found (P = 0.71; I2 = 0.0%) even though a study performed in rabbits was included in this meta-analysis. Comparison of the effects of glucocorticoids administration before or after inducing SAP on the risk of mortality revealed reduced mortality in both groups (before; RR 0.46 [0.24, 0.88]; n = 3; after; RR 0.24 [0.1, 0.54]; n = 4). Subgroup analyses on the study characteristic “equivalent dosage of dexamethasone” also showed improvement in mortality regardless of the dosage (large RR 0.38 [0.22, 0.65]; n = 6; low RR 0.15 [0.02, 0.92]; n = 1) (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Forest plot of effects of glucocorticoids supplementation on mortality in experimental acute pancreatitis. Forest plot of the data of seven included studies. The forest plot displays the OR, 95% confidence interval and relative weight of the individual studies. The diamond indicates the global estimate and its 95% confidence interval.

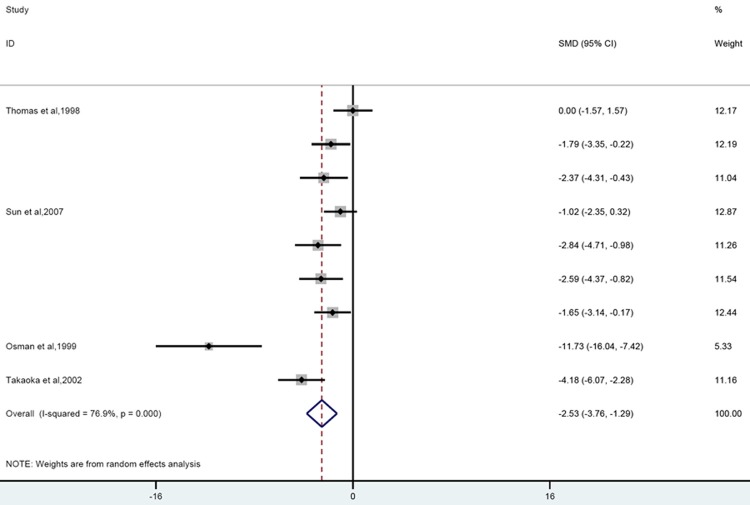

Ascites

Four papers including 9 experiments reported change of pancreatic ascites production due to corticosteroid treatment. Overall analysis showed that corticosteroid significantly reduced the volume of ascites compared to controls (SMD = -2.53 [-3.76, -1.29]; n = 9; P = 0.000). Heterogeneity was high (P = 0.000; I2 = 76.9%) and remained moderate after eliminating the study performed in rabbits (P = 0.04; I2 = 52.3%) (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Forest plot of the effects of glucocorticoids supplementation on volume of ascites in experimental acute pancreatitis. The forest plot displays the SMD, 95% confidence interval and relative weight of the individual studies. The diamond indicates t he global estimate and its 95% confidence interval.

Prior treatment diminished the output of the ascitic fluids significantly (SMD = -3.29 [-5.03, -1.54]; n = 6; P = 0.000), no significant decrease was observed when these agents were employed after AP induction (SMD = -1.32 [-2.72, 0.08]; n = 3; P = 0.124). Stratification by dosage revealed that large dose was more potent in decreasing the volume of ascitic fluids compared to low dose group (large; SMD = -4.35 [-7.11, -1.59]; n = 4; P = 0.000 low; SMD = -1.53 [-2.5, -0.56]; n = 5; P = 0.113). Subgroup analysis did not reduce heterogeneity obviously (Data were shown in Table 2).

Table 2.

Subgroup analysis of the effects of glucocorticoids supplementation on volume of ascites in experimental acute pancreatitis

| Volume of ascites | SMD | LL | UL | n | p | p of hetergeneity | I2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | -2.53 | -3.76 | -1.29 | 9 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 76.90% |

| Timing of treatment | |||||||

| Prophylactic (before) | -3.29 | -5.03 | -1.54 | 6 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 81.30% |

| Therapeutic (after) | -1.32 | -2.72 | 0.08 | 3 | 0.065 | 0.124 | 52% |

| Equivalent dosage of Dx | |||||||

| Large | -4.35 | -7.11 | -1.59 | 4 | 0.002 | 0.000 | 84.90% |

| low | -1.53 | -2.5 | -0.56 | 5 | 0.002 | 0.113 | 46.50% |

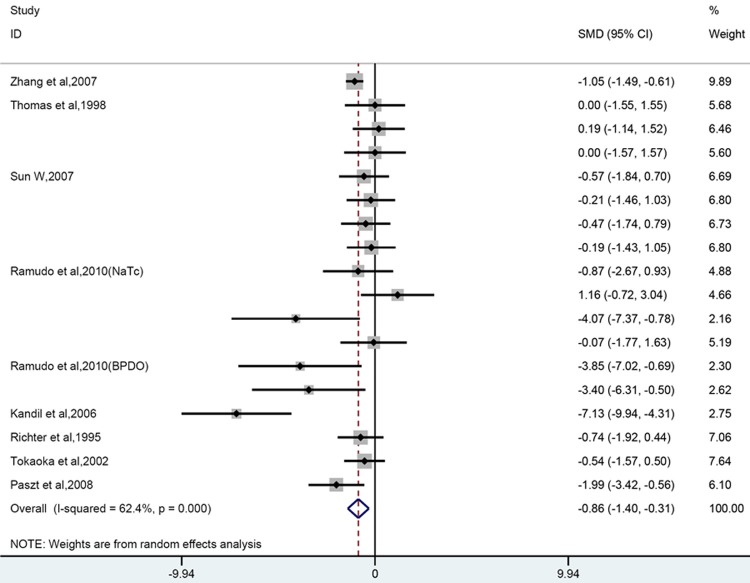

Histopathology of the pancreas

Nine out of 17 papers could be included in quantitative analysis, which covered 18 comparisons in total. Overall analysis showed that glucocorticoids can reduced/improved the histopathology of the pancreas (SMD = -0.86 [-1.40, -0.31]; n = 18; P = 0.002) (Figure 5). Heterogeneity was high (P = 0.000, I2 = 62.4%). Subgroup analysis revealed that prophylactic corticosteroid use significantly decrease the pathological score, whereas no significant change was observed in therapeutic use group (before; SMD = -1.23 [-2.12 -0.34]; n = 9; P = 0.007; after; SMD = -0.54 [-1.28, 0.20]; n = 9; P = 0.152). Taking into account of dosage, large dose group significantly ameliorated histopathology, both low and moderate groups did not (low; SMD =-0.39 [-0.91, 0.13]; n = 6; P = 0.14; moderate; SMD = -1.48 [-3.13, 0.17]; n = 6; P = 0.078; large; SMD = -0.94 [-1.61, -0.27]; n = 6; P = 0.021).

Figure 5.

Forest plot of the effects of glucocorticoids supplementation on histopathological damage to the pancreas in experimental acute pancreatitis. The forest plot displays the SMD, 95% confidence interval and relative weight of the individual studies. The diamond indicates the global estimate and its 95% confidence interval.

Subgroup analyses also revealed that the significant efficacy was only observed in dexamethasone group(dexamethasone; SMD = -2.01 [-3.42, 0.6]; n = 8; P = 0.005; hydrocortisone; SMD = -0.36 [-0.99, 0.27]; n = 4; P = 0.855; methylprednisolone; SMD = -1.18 [-2.59, 0.24]; n = 2; P = 0.103; prednisone or prednisolone; SMD = -0.2 [-0.89, 0.49]; n = 4; P = 0.568). When our study were further subdivided by other characteristics, namely delivery rout, gender or strain, method of AP induction and timing for outcome measurement, we found no efficacy were found in female or mixed sex groups and outcome measurement time longer than 36h. Subgroup analysis reduced heterogeneity of low dose or hydrocortisone and SD rat group. (Data were shown in Table 3).

Table 3.

Subgroup analysis of the data of the effects of glucocorticoids supplementation to the pancreas in experimental acute pancreatitis

| Histopathology pancreas | SMD | LL | UL | n | p | p of hetergeneity | I2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | -0.86 | -1.4 | -0.31 | 18 | 0.002 | 0 | 62.40% |

| Timing of treatment | |||||||

| Prophylactic (before) | -1.23 | -2.12 | -0.34 | 9 | 0.007 | 0 | 71.40% |

| Therapeutic (after) | -0.54 | -1.28 | 0.2 | 9 | 0.152 | 0.029 | 53.40% |

| Equivalent dosage of Dx | |||||||

| Large | -0.94 | -1.61 | -0.27 | 6 | 0.021 | 0 | 80.40% |

| Moderate | -1.48 | -3.13 | 0.17 | 6 | 0.078 | 0.009 | 67.40% |

| Low | -0.39 | -0.91 | 0.13 | 6 | 0.14 | 0.974 | 0% |

| Type of glucocorticoid | |||||||

| Dx | -2.01 | -3.42 | 0.6 | 8 | 0.005 | 0 | 78.90% |

| Hc | -0.36 | -0.99 | 0.27 | 4 | 0.855 | 0.968 | 0% |

| Mp | -1.18 | -2.59 | 0.24 | 2 | 0.103 | 0.107 | 61.50% |

| Pre or pred | -0.2 | -0.89 | 0.49 | 4 | 0.568 | 0.736 | 0% |

| Rout of drug dilivery | |||||||

| Iv | -0.69 | -1.1 | -0.28 | 6 | 0.001 | 0.347 | 10.70% |

| Non-iv | -1.37 | -2.33 | -0.41 | 12 | 0.005 | 0 | 72.10% |

| Gender of animals used | |||||||

| Male | -0.79 | -1.41 | -0.16 | 12 | 0.014 | 0.015 | 53.30% |

| Female | -0.74 | -1.92 | 0.44 | 1 | 0.218 | null | null |

| Unknown | -1.26 | -2.73 | 0.22 | 5 | 0.094 | 0 | 81.30% |

| Species | |||||||

| SD | -0.67 | -1.01 | -0.34 | 8 | 0 | 0.424 | 0.70% |

| Wistar | -1.75 | -2.91 | -0.59 | 10 | 0.003 | 0 | 75.00% |

| Time for outcome measurement | |||||||

| ≤ 6 h | -0.61 | -1.11 | -0.12 | 9 | 0.015 | 0.178 | 30.10% |

| 12-24 h | -2.51 | -4.81 | -0.84 | 6 | 0.003 | 0 | 80.20% |

| ≥ 36 h | 0.08 | -0.77 | 0.93 | 3 | 0.855 | 0.975 | 0% |

| Method of AP induction | |||||||

| NaTc | -1.61 | -3.2 | -0.02 | 6 | 0.047 | 0 | 82% |

| non-NaTc | -0.60 | -1.07 | -0.13 | 12 | 0.012 | 0.2 | 24.90% |

Sensitivity analysis and publication bias

When a single study involved in the meta-analysis was deleted each time, the results of meta-analysis remained unchanged, indicating that the results of the present meta-analysis were stable (data not shown). There was no statistical evidence of publication bias among studies for both mortality and histopathology of pancreas by using Egger’s test (P = 0.17; P = 0.44, respectively). For volume of ascites, Egger’s test revealed significant publication bias (P = 0.001). The overall conclusion indicated no overestimation after Trim and fill analysis filled with two studies (SMD = -3.29 [-4.7, -1.89]; n = 11; P = 0.000).

Discussion

The results of this meta-analysis showed the beneficial effects of glucocorticoids with regard to the primary outcome measure survival in animal studies of SAP whenever these agents were employed prophylactically or therapeutically. When it came to other outcome measures (changes of pancreatic ascites and histopathology of pancreas), overall analysis also showed a positive effect, however, subgroup analyses indicated that the improvement was not statistically significant in therapeutic treatment group. Furthermore, efficacy seemed to be influenced by dosage and type of steroids, strains or genders, drug delivery routes et al and part of those characteristics accounted for a quite considerable proportion of between-study heterogeneity.

Despite the improvements in intensive care and surgical therapy, the mortality rate for acute necrotizing pancreatitis remains high [44]. The clinical presentation may range from a local inflammatory process to a severe pancreas injury associated with extra-pancreatic manifestations such as circulatory, renal or pulmonary complications [45,46]. Activation of the inflammatory cascade mediated by various inflammatory mediators is the key causes of acute pancreatitis aggravation, eventually results in microcirculatory disturbances, multiple organ failure and even death [46]. Glucocorticoids are potent anti-inflammatory drugs, both directly and indirectly attenuating the synthesis, release, and action of inflammatory cytokines and certain other mediators [6]. It is therefore assumed that glucocorticoids could alleviate the severity of AP in terms of its inhibitory role in excessive inflammatory reactions. Among our included studies, many indicated that exogenous glucocorticoids significantly improved both the local pancreatic inflammatory response as well as systemic inflammatory parameters including the serum concentrations of tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-alpha), interleukins (ILs), platelet-activating factor and C-reactive protein et al. [30,32,35,38,41]. Furthermore, glucocorticoids were found to attenuate the pancreas damage by protecting acinar cells during cerulein-induced AP [7]. In the Journal of Gastroenterology, Takaoka et al. [39] have very clearly shown that in rats with SAP induced by a closed duodenal loop, the intravenous administration of methylprednisolone (30 mg/kg) alleviated the severity of the acute pancreatitis in terms of pancreatic edema formation and elevation of serum amylase, as well as alleviating its complications the production of ascites through vascular permeability.

Our results showed that corticosteroid is effective at reducing pancreatic ascites production and histopathological score of pancreas and improving survival in experimental models of SAP. It is noteworthy in our study that the short-term pre-treatment with glucocorticoids resulted in both reducing pancreatic ascites and ameliorating histopathology of pancreas, however, post-treatment proved to be ineffective to hinder pancreatic damage and pancreatic ascites production. A plausible mechanism by which may explain the observation was the tight association between inflammatory response and severity of AP. Prophylactic treatment can limit both the local and systemic inflammatory response at the very earliest phase, which resulted in a beneficial effect on the progression of the disease in all directions. Therapeutic treatment just partly blocked inflammatory responses, so the improvement were not statistical significant. However, longer survival has been achieved, demonstrating its beneficial potential in overall prognosis. Taking the dose and type of steroids into consideration, less ascites and improved histopathology of pancreas was found in large dose and dexamethasone groups. The anti-inflammatory potency of glucocorticoid compound was different from each other, it was quite reasonable to find that dexamethasone (with stronger anti-inflammatory potency) showed a positive effectiveness whereas cortisone, hydrocortisone or prednisone (with weaker anti-inflammatory potency) did not in this setting, so did the large dose of steroids.

The design of prophylactic use in an animal study could be clinically relevant with studies which evaluated the preventive role of corticosteroids in post-ERCP pancreatitis. In light of the results presented above-mentioned strong evidence for efficacy of prophylactic use, it was defensible and understandable that the clinical trials were started [17,18]. However, Giovanni et al. [47] showed in a controlled prospective study involving 529 patients, that 100 mg of hydrocortisone did not significantly affect acute pancreatitis after diagnostic or therapeutic-ERCP, and the latest meta-analysis suggested that prophylactic corticosteroid use cannot prevent pancreatic injury after ERCP and their use in the prophylaxis of post-ERCP pancreatitis is not recommended [19]. Nearly all interventions which have shown promise in preclinical studies have failed to translate successfully to the clinical setting. In our study, lack of correspondence between animal data and results from clinical trials might be explained below: first of all, glucocorticoids are potent anti-inflammatory drugs and can improved inflammatory mediated pancreas damage, but the beneficial effect itself is not strong enough to improve the final clinical results. More importantly, clinical trials mostly used hydrocortisone and sex in their groups was balanced, whereas most of our studies used dexamethasone and male Wistar rat models were more common. When the study was subdivided by type of steroids and sex of rodents, we found no significant relationship between corticosteroid use and improved histopathology of pancreas in hydrocortisone and female or sex-mixed groups. From the point of view, the results in animal studies might correspond well to clinical studies. Additionally, animal studies are prone to bias, mostly overestimation of the treatment [48]. Therefore, contradictory results might arise from lack of control of bias and more appropriate animal experiments in relation to the design of human studies.

The utilization of steroid for therapeutic purposes in the patients with acute pancreatitis is still controversial, and the effectiveness has been suspected for many years. Case reports from several decades ago have suggested a potential clinical benefit of hydrocortisone in acute hemorrhagic pancreatitis [49]. However, the available data with positive results about steroid in acute pancreatitis up to now were mostly experimental studies [33]. In our meta-analysis, the efficacy was not statistically significant in therapeutic treatment group with regard to ascitic fluid production and histopathology of pancreas, whereas better survival was observed, indicating the possible usefulness of the steroid therapy for SAP. It might be worthwhile to investigate this point further clinically. However, the beneficial findings of prophylactic steroids use obtained in rodent animal studies were not validated in interventional clinical studies. Therefore, we assumed that therapeutic corticosteroid use in SAP could also lead to no benefit in clinical application, not only because of the previous inconsistency but also for its relatively lower efficacy even in animal studies. Even for prolonged survival, we should interpret with caution because of data collection time in animal studies. Corticosteroid significantly improved recent mortality in animal studies, within these, the longest observation time was 72 hours, in other word, effects of corticosteroid on late mortality was not investigated at all. However, SAP is characterized by completely different two phases. The early phase is associated with SIRS, multiple organ damage and early mortality, the late phase is characterized by infections; so whether corticosteroid improve overall survival need to be elucidated by further experimental studies. Furthermore, as known to all of us, corticosteroid has unpleasant side effects, even induction of AP, whereas no safety data in these animal studies has been discussed, so further appropriate and informative animal experiments should be performed before conducting clinical trials.

Taking consideration of the meta-analysis itself, there are limitations to our approach. First, although our search strategy was designed to be robust, we cannot rule out the possibility of missing studies. Second, the heterogeneity among the various animal studies was quite considerable. We performed a random effect meta-analysis in order to minimize the risk of finding erroneous estimates offering more consistent results. Our analysis was based on study mean effects, as we did not have access to individual data. Study characteristics actually accounted for a quite considerable proportion of between-study heterogeneity, but the results of these sensitivity and stratified analyses should be interpreted with caution for small number of experiments in some subgroups interactions. Furthermore, only half of the studies reported that they blinded the outcome assessment and only one study provided sufficient details to judge the adequacy of the method of randomization, so the methodological quality of the individual animal studies urgently need to be improved in order to increase the potential value of animal studies as a preparation for clinical applications.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first meta-analysis to evaluate the effect of glucocorticoids in rodent animal models. This meta-analysis has demonstrated the beneficial effects of glucocorticoids with regard to the primary outcome measure survival irrespective of administration before or after AP induction. In addition, significant effectiveness has been obtained on both reduced histopathology of pancreas and ascitic fluid production for prophylactic use before AP induction, whereas therapeutic use after AP induction did not. For prophylactic use, contradictory results might arise from lack of more appropriate animal experiments in relation to the design of human studies. Further appropriate and informative animal experiments should be performed before conducting clinical trials.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No: 81060038 and 81270479), and grants from Jiangxi Province Talent 555 Project, the National Science and Technology Major Projects for “Major New Drug Innovation and Development” of China (No: 2011ZX09302-007-03).

Disclosure of conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Agapov MA, Khoreva MV, Gorskii VA. The systemic inflammatory response syndrome correction in acute destructive pancreatitis. Eksp Klin Gastroenterol. 2011:18–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cruz-Santamaria DM, Taxonera C, Giner M. Update on pathogenesis and clinical management of acute pancreatitis. World J Gastrointest Pathophysiol. 2012;3:60–70. doi: 10.4291/wjgp.v3.i3.60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mofidi R, Duff MD, Wigmore SJ, Madhavan KK, Garden OJ, Parks RW. Association between early systemic inflammatory response, severity of multiorgan dysfunction and death in acute pancreatitis. Br J Surg. 2006;93:738–744. doi: 10.1002/bjs.5290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Miranda CJ, Babu BI, Siriwardena AK. Recombinant human activated protein C as a disease modifier in severe acute pancreatitis: Systematic review of current evidence. Pancreatology. 2012;12:119–123. doi: 10.1016/j.pan.2012.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gregoric P, Sijacki A, Stankovic S, Radenkovic D, Ivancevic N, Karamarkovic A, Popovic N, Karadzic B, Stijak L, Stefanovic B, Milosevic Z, Bajec D. SIRS score on admission and initial concentration of IL-6 as severe acute pancreatitis outcome predictors. Hepatogastroenterology. 2010;57:349–353. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brattsand R, Linden M. Cytokine modulation by glucocorticoids: Mechanisms and actions in cellular studies. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1996;10(Suppl 2):81–90. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.1996.22164025.x. discussion 91-92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kimura K, Shimosegawa T, Sasano H, Abe R, Satoh A, Masamune A, Koizumi M, Nagura H, Toyota T. Endogenous glucocorticoids decrease the acinar cell sensitivity to apoptosis during cerulein pancreatitis in rats. Gastroenterology. 1998;114:372–381. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(98)70490-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mossner J, Bohm S, Fischbach W. Role of glucocorticosteroids in the regulation of pancreatic amylase synthesis. Pancreas. 1989;4:194–203. doi: 10.1097/00006676-198904000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Studley JG, Schenk WJ. Pathophysiology of acute pancreatitis: Evaluation of the effect and mode of action of steroids in experimental pancreatitis in dogs. Am J Surg. 1982;143:761–764. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(82)90054-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lium B, Ruud TE, Pillgram-Larsen J, Stadaas JO, Aasen AO. Sodium taurocholate-induced acute pancreatitis in pigs. Pathomorphological studies of the pancreas in untreated animals and animals pretreated with high doses of corticosteroids or protease inhibitors. Acta Pathol Microbiol Immunol Scand A. 1987;95:377–382. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barzilai A, Ryback BJ, Medina JA, Toth L, Dreiling DA. The morphological changes of the pancreas in hypovolemic shock and the effect of pretreatment with steroids. Int J Pancreatol. 1987;2:23–32. doi: 10.1007/BF02788346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gomez G, Townsend CJ, Green D, Rajaraman S, Uchida T, Thompson JC. Involvement of cholecystokinin receptors in the adverse effect of glucocorticoids on diet-induced necrotizing pancreatitis. Surgery. 1989;106:230–236. discussion 237-238. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Monto GL, Guillan RA, Lee SH, Watanabe I. Assessment of corticosteroid treatment of ethionine pancreatitis in the rabbit. Am J Gastroenterol. 1983;78:63–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kimura T, Zuidema GD, Cameron JL. Acute pancreatitis. Experimental evaluation of steroid, albumin and trasylol therapy. Am J Surg. 1980;140:403–408. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(80)90178-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Riemenschneider TA, Wilson JF, Vernier RL. Glucocorticoid-induced pancreatitis in children. Pediatrics. 1968;41:428–437. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Manolakopoulos S, Avgerinos A, Vlachogiannakos J, Armonis A, Viazis N, Papadimitriou N, Mathou N, Stefanidis G, Rekoumis G, Vienna E, Tzourmakliotis D, Raptis SA. Octreotide versus hydrocortisone versus placebo in the prevention of post-ERCP pancreatitis: A multicenter randomized controlled trial. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;55:470–475. doi: 10.1067/mge.2002.122614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Budzynska A, Marek T, Nowak A, Kaczor R, Nowakowska-Dulawa E. A prospective, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of prednisone and allopurinol in the prevention of ERCP-induced pancreatitis. Endoscopy. 2001;33:766–772. doi: 10.1055/s-2001-16520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sherman S, Blaut U, Watkins JL, Barnett J, Freeman M, Geenen J, Ryan M, Parker H, Frakes JT, Fogel EL, Silverman WB, Dua KS, Aliperti G, Yakshe P, Uzer M, Jones W, Goff J, Earle D, Temkit M, Lehman GA. Does prophylactic administration of corticosteroid reduce the risk and severity of post-ERCP pancreatitis: A randomized, prospective, multicenter study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;58:23–29. doi: 10.1067/mge.2003.307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zheng M, Bai J, Yuan B, Lin F, You J, Lu M, Gong Y, Chen Y. Meta-analysis of prophylactic corticosteroid use in post-ERCP pancreatitis. BMC Gastroenterol. 2008;8:6. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-8-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pound P, Ebrahim S, Sandercock P, Bracken MB, Roberts I. Where is the evidence that animal research benefits humans? BMJ. 2004;328:514–517. doi: 10.1136/bmj.328.7438.514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sena E, van der Worp HB, Howells D, Macleod M. How can we improve the pre-clinical development of drugs for stroke? Trends Neurosci. 2007;30:433–439. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2007.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu ZH, Peng JS, Li CJ, Yang ZL, Xiang J, Song H, Wu XB, Chen JR, Diao DC. A simple taurocholate-induced model of severe acute pancreatitis in rats. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:5732–5739. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.5732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Furlan AD, Pennick V, Bombardier C, van Tulder M; Editorial Board, Cochrane Back Review Group. 2009 updated method guidelines for systematic reviews in the Cochrane Back Review Group. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2009;34:1929–1941. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181b1c99f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hooijmans CR, de Vries RB, Rovers MM, Gooszen HG, Ritskes-Hoitinga M. The effects of probiotic supplementation on experimental acute pancreatitis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2012;7:e48811. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0048811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vesterinen HM, Currie GL, Carter S, Mee S, Watzlawick R, Egan KJ, Macleod MR, Sena ES. Systematic review and stratified meta-analysis of the efficacy of RhoA and Rho kinase inhibitors in animal models of ischaemic stroke. Syst Rev. 2013;2:33. doi: 10.1186/2046-4053-2-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7:177–188. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327:557–560. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Begg CB, Mazumdar M. Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics. 1994;50:1088–1101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Foitzik T, Forgacs B, Ryschich E, Hotz H, Gebhardt MM, Buhr HJ, Klar E. Effect of different immunosuppressive agents on acute pancreatitis: A comparative study in an improved animal model. Transplantation. 1998;65:1030–1036. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199804270-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ramudo L, Yubero S, Manso MA, Recio JS, Weruaga E, De Dios I. Effect of dexamethasone on peripheral blood leukocyte immune response in bile-pancreatic duct obstruction-induced acute pancreatitis. Steroids. 2010;75:362–367. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2010.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ramudo L, Yubero S, Manso MA, Sanchez-Recio J, Weruaga E, De Dios I. Effects of dexamethasone on intercellular adhesion molecule 1 expression and inflammatory response in necrotizing acute pancreatitis in rats. Pancreas. 2010;39:1057–1063. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e3181da0f3e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gloor B, Uhl W, Tcholakov O, Roggo A, Muller CA, Worni M, Buchler MW. Hydrocortisone treatment of early SIRS in acute experimental pancreatitis. Dig Dis Sci. 2001;46:2154–2161. doi: 10.1023/a:1011902729392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang XP, Zhang L, Wang Y, Cheng QH, Wang JM, Cai W, Shen HP, Cai J. Study of the protective effects of dexamethasone on multiple organ injury in rats with severe acute pancreatitis. JOP. 2007;8:400–412. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Muller CA, Belyaev O, Appelros S, Buchler M, Uhl W, Borgstrom A. Dexamethasone affects inflammation but not trypsinogen activation in experimental acute pancreatitis. Eur Surg Res. 2008;40:317–324. doi: 10.1159/000118027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang ZF, Pan CE, Lu Y, Liu SG, Zhang GJ, Zhang XB. The role of inflammatory mediators in severe acute pancreatitis and regulation of glucocorticoids. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2003;2:458–462. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ou JM, Zhang XP, Wu CJ, Wu DJ, Yan P. Effects of dexamethasone and Salvia miltiorrhiza on multiple organs in rats with severe acute pancreatitis. J Zhejiang Univ Sci B. 2012;13:919–931. doi: 10.1631/jzus.B1100351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kandil E, Lin YY, Bluth MH, Zhang H, Levi G, Zenilman ME. Dexamethasone mediates protection against acute pancreatitis via upregulation of pancreatitis-associated proteins. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:6806–6811. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i42.6806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Paszt A, Takacs T, Rakonczay Z, Kaszaki J, Wolfard A, Tiszlavicz L, Lazar G, Duda E, Szentpali K, Czako L, Boros M, Balogh A, Lazar GJ. The role of the glucocorticoid-dependent mechanism in the progression of sodium taurocholate-induced acute pancreatitis in the rat. Pancreas. 2004;29:75–82. doi: 10.1097/00006676-200407000-00059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Takaoka K, Kataoka K, Sakagami J. The effect of steroid pulse therapy on the development of acute pancreatitis induced by closed duodenal loop in rats. J Gastroenterol. 2002;37:537–542. doi: 10.1007/s005350200083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Paszt A, Eder K, Szabolcs A, Tiszlavicz L, Lazar G, Duda E, Takacs T, Lazar GJ. Effects of glucocorticoid agonist and antagonist on the pathogenesis of L-arginine-induced acute pancreatitis in rat. Pancreas. 2008;36:369–376. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e31815bd26a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Osman MO, Jacobsen NO, Kristensen JU, Larsen CG, Jensen SL. Beneficial effects of hydrocortisone in a model of experimental acute pancreatitis. Dig Surg. 1999;16:214–221. doi: 10.1159/000018730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sun W, Watanabe Y, Toki A, Wang ZQ. Beneficial effects of hydrocortisone in induced acute pancreatitis of rats. Chin Med J (Engl) 2007;120:1757–1761. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Richter F, Matthias R. Survival and morphology of isolated pancreatic acinar cells from rats with induced acute pancreatitis are not improved with anti-inflammatory drugs. Int J Pancreatol. 1995;18:145–152. doi: 10.1007/BF02785888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Heinrich S, Schafer M, Rousson V, Clavien PA. Evidence-based treatment of acute pancreatitis: A look at established paradigms. Ann Surg. 2006;243:154–168. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000197334.58374.70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Klar E, Messmer K, Warshaw AL, Herfarth C. Pancreatic ischaemia in experimental acute pancreatitis: Mechanism, significance and therapy. Br J Surg. 1990;77:1205–1210. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800771104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Werner J, Dragotakes SC, Fernandez-del CC, Rivera JA, Ou J, Rattner DW, Fischman AJ, Warshaw AL. Technetium-99m-labeled white blood cells: A new method to define the local and systemic role of leukocytes in acute experimental pancreatitis. Ann Surg. 1998;227:86–94. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199801000-00013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.De Palma GD, Catanzano C. Use of corticosteriods in the prevention of post-ERCP pancreatitis: Results of a controlled prospective study. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:982–985. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.999_u.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tsilidis KK, Panagiotou OA, Sena ES, Aretouli E, Evangelou E, Howells DW, Al-Shahi SR, Macleod MR, Ioannidis JP. Evaluation of excess significance bias in animal studies of neurological diseases. PLoS Biol. 2013;11:e1001609. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Stephenson HJ, Pfeffer RB, Saypol GM. Acute hemorrhagic pancreatitis; Report of a case with cortisone treatment. Ama Arch Surg. 1952;65:307–308. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]